The Grape Boom in the Old South

The main movements in eastern American winegrowing before the Civil War—main in the sense that they led to a continuing industry—were in New York State, northern Ohio, and Missouri. It would be quite wrong, however, to neglect the scattered but frequent efforts at winegrowing throughout the old South. We have seen how, in New York, Ohio, and Missouri, winegrowing not only continued but made considerable advances in size and prosperity throughout the war. In the South, however, it was severely cut back, and it is therefore of some historical interest to see just how widespread interest in it was before Fort Sumter stopped all that.

In Virginia, home of the oldest of all winegrowing traditions in this country, the record is meager. There was evidently a good deal of farm-scale winemaking from native grapes, but nothing more. Perhaps the state's best contribution was the Norton grape, which became so important in the vineyards of Missouri; there is some evidence that commercial plantings of Norton were made in Virginia too before the war, around Charlottesville.[55]

Scuppernong wine continued to flourish as the vin de pays of North Carolina. Its most energetic sponsor was a Yankee named Sidney Weller, a graduate of Union College in New York State, who took over a worn-out farm of some three hundred acres at Brinckleyville, Halifax County, in the late 1820s and began to carry out his progressive ideas on agriculture.[56] In addition to general farming, he went in for winegrowing, based largely on the Scuppernong but including the Norton and a labrusca called Halifax as well.[57] Weller was a good promoter, who filled the agricultural press with accounts of what he called his "American system" of viticulture: this was, in substance, simply to allow his Scuppernong vines unchecked growth on trellises instead of controlling them by any system of pruning: such freedom, presumably, could only be called "American."[58] From grapes grown in this liberated fashion on some twelve acres of vineyard (the largest in the South, Weller thought), he produced several thousands of gallons yearly of scuppernong "hock" and "champagne," which he was able to sell at prices from $1 to $6 a gallon to markets as distant as New York, New Orleans, and St. Louis.[59] He also made his vineyards a place of public resort, charging admission to picnickers and so adding measurably to the land's revenue. In the hands of his son John, Weller's winemaking business continued down to the Civil War.[60] It was afterwards the basis from which Paul Garrett's important winemaking business grew to national prominence.[61]

There were enough other producers of scuppernong wines in North Carolina besides Weller to make the state the nation's largest producer in 1840;[62] grapes were, according to one account, the main crop of the coastal "Bankers and islanders." The wine they made, however, was really only a fortified grape juice.[63] The hope of growing something better than Scuppernong persisted, but instead of sticking with such natives as the Herbemont, Lenoir, or Norton, all of which had been proven in the South, some experimenters, at least, went back to vinifera, with predictable results. Around 1849 Dr. Joseph Togno established a vineyard near Wilmington that he called the North Carolina Vine Dresser and Horticultural Model Practical School.[64] Togno's experience went far back—he claimed to have cultivated vinifera in Fauquier County, Virginia, in 1821 and 1822. His "School" advertised in 1849 that it stood ready to receive "pupils, over 14 years old, attended with or without slave, to learn all the manipulations of the Vineyard, the orchard, and horticulture in general." Togno had imported European vines for his vineyard, and after a year he reported that they were doing well and that he intended to graft them to native rootstocks. But then the enterprise failed. After their first delusive growth, the vinifera vines succumbed to the local diseases. That, however, might have been surmounted, since Togno had learned to appreciate the possibilities of the native vine, especially the Scuppernong, which he proclaimed the "American champagne grape par excellence; its aromatic bouquet making it superior to the Pinot, or Pineau of Champagne."[65] It was one thing to grow grapes; it was quite another to attract young southerners to the study of winemaking. As Togno sadly wrote in 1853, after four years he had had not a single application for admission to his school, and the local Tarheels called the place "Dr. Togno's Folly."[66] Not long

65

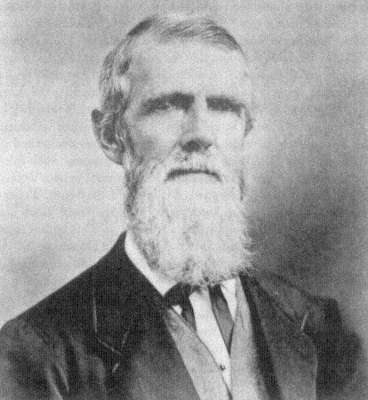

Henry William Ravenel (1814-87), member of the Vine-Growing and

Horticultural Association of Aiken, South Carolina, founded in 1858.

Ravenel, descended from one of the old Huguenot families of South

Carolina, continued in the nineteenth century the trials of winegrowing

that the Huguenots had begun in the seventeenth century. One of the

most eminent of botanists in nineteenth-century America, he maintained

a vineyard at his home, Hampton Hill. (From The Private Journal of Henry

William Ravenel, 1859-1887 [1947])

after poor Togno's debacle we hear of a Frenchman named Kron growing vines and making wine in the far western part of the state around 1860; he had native grapes, especially the Herbemont, but he had also imported vines from France.[67] They would not have survived even if war had not come.

In South Carolina the interesting development just before the war was the formation of the Aiken Horticultural and Vine-Growing Association in 1858, which addressed itself to the central problem of obtaining satisfactory varieties. It hoped to do so "by the raising of seedlings," and offered "handsome premiums towards that object."[68] The leaders of the association included Dr. J. C. W. McDonnald[69] and H. W. Ravenel of Aiken; D. Redmond of Augusta, Georgia, well known as the editor of the Southern Cultivator and as an enthusiastic propagator and grower of grapes; and Achille de Caradeuc of Woodward, who had been making wine since 1851[70] and who published his Grape Culture and Winemaking in the South in 1858.

Ravenel, who was president of the association in 1860, was a descendant of the South Carolina Huguenots and so a link in that chain of winegrowing tradition. He was a botanist of international distinction, and though his special interest was in fungi, he did not neglect the grape. He produced wine from his vineyard, took a prize for "the best foreign grapes" at the association's competition, read a paper on pruning vines to the association, and, after the war, published articles on viticulture.[71]

There were other vineyards then scattered about the state at Charleston, Kalmia, Columbia, Orangeburg, Bluffton, Kaolin, and Redcliffe. The war, obviously, was a severe check to their activity, yet within a year after the war the region around Aiken was reported to have from three to five hundred acres of vines, and wine was being made there in commercial quantity.[72]

The Aiken people, in common with many others in the latter years of the 1850s, were responding to the prospect that the news of oidium in Europe seemed to open. While production in Europe declined precipitously, how could production in the United States fail to enrich the grower? To southerners especially the proposition seemed foolproof, for they had slaves to do the work: as one enthusiast put it, "with all the facilities we possess at the South, with our soil, climate, and more particularly our slaves, nothing can prevent ours from becoming the greatest wine country that ever was."[73] Since the Civil War, to look no farther for reasons, did in fact prevent any such development, the prophecy now looks notably foolish. Yet the writer was talking sense. Grapes had certainly been grown in the South, and who knows what concerted and determined experimentation might not have done? Hope persisted against the heaviest discouragement. During the dark days of the war, the old South Carolinian politician William John Grayson, retired to the country and writing his recollections, noted that the making of wine had not ceased in South Carolina but was "gradually extending in various parts of the state. Some centuries hence our State may be as famous for wine as for cotton or rice." This was taking a very long view indeed.[74]

The Aiken people were also responding to the activity of a German, a Rhinelander named Charles Axt, who had come to Georgia in 1848, had been mightily struck by the vitality of the native vines, and had gone about the Piedmont region of the state since the early 1850s propagandizing for grape culture in broken English—the "itinerant Grape Missionary" he was called.[75] Since the cotton farmers of the region needed another cash crop, and since their lands were running more and more to gullies and washed-out red dirt under the destructive practices of cotton monoculture, Axt found men willing to listen. They especially liked the numbers that he used. He would, he said, undertake to plant and supervise a small vineyard of a quarter of an acre on a client's land; he would tend it for three years at $50 per annum; and at the end of that time he would deliver 350 gallons of wine. That was only a beginning, to show what might be done. After five years, he claimed, he could make an acre yield 2,500 gallons (or roughly the yield from an impossible sixteen tons of grapes). Probably no one ever held him to his claim.

By 1855 he was doing well, supervising vineyards in Georgia, South Carolina,

and Alabama, and operating his own at Crawfordville, not far west of Augusta. This was not bad for a man who had come to Georgia with no capital and little English just seven years earlier. Catawba seems to have been the vine of choice for Axt, but the vineyards of Georgia contained the old southern varieties such as Herbemont and Lenoir too. In 1856 a Vine Growers' Association of Georgia was formed; by 1857 Axt had commercial quantities of catawba in local markets, and had won over all opinion in favor of his vision of the Piedmont as wine country. The Belgian horticulturist Louis E. Berckmans, who had migrated from New Jersey to Augusta to operate a nursery there, described the prospect thus:

In places where no corn or rye will grow I have seen many a goodly acre covered with Catawba and Warren grapes, and yielding from four hundred to six hundred dollars, in soils abandoned as unfit for every other cultivation. South Carolina and Georgia will soon be awake to this new enterprise and acres upon acres of land not worth five dollars are going to be converted into vineyards to supply the union with wine, equal if not superior to any Hock or Madeira.[76]

The last few years before the war saw a grape mania in the South quite as intense as the one sweeping the North at the same time. Vineyards large and small sprang up in Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana, as well as in the older seaboard states and in the less cotton-dominated states of Kentucky and Tennessee. The southern agricultural papers were filled with a lively correspondence reporting developments, offering advice, disputing questions, and prophesying the future of southern wines and vines. The climactic moment may be located in August 1860, when, on the initiative of the Aiken Horticultural and Vine-Growing Association, a general convention of all interested vine growers in the United States was summoned to a grand meeting at Aiken.[77] The response from the North was chilly—it could hardly be expected, as one northern paper remarked, that people would wish to visit a southern town at the height of the summer.[78] Growers from the South were less troubled by the thought.

When it met at the Baptist Church in Aiken, the convention was largely made up of delegates from Georgia and South Carolina, who called themselves the Southern Vine Growers' Convention and were presided over by James Hammond, a former governor of South Carolina who was himself a winegrower. One of their objects was to establish exact botanical descriptions of grape varieties; another was to "determine upon some manner of naming the different wines"[79] —a subject bristling with problems that are still far from resolved. Varietal naming, which many think of as a recent introduction, was in fact already the standard American practice.[80] But it seemed most unsatisfactory in place of the traditional European principle of naming by place, for the plain reason that, as the prospectus of the convention put it: "the same grape will make totally different wines in different places"—a proposition as true today as it ever was then. As one convention speaker argued, with hundreds of catawba and Warren wines available, and no two of them alike, the names "catawba" and "Warren" could guarantee nothing at all. Place names, brands, or private names were what were wanted.[81]

Furthermore, varietal naming made no proper provision for blends of more than one sort of grape. How could you call it catawba if it was really Catawba, Lenoir, and Scuppernong? The proposals for labelling recommended by the convention were, first, the name of the state, followed by the town or other local name (river, hill, valley, or the like), and then the maker's name or brand. Nothing was allowed for the variety or varieties of grape.[82] The scheme is evidently not a perfect one, but it is interesting evidence of the way in which the difficulty—still being agitated as I write—of naming the wines of a new country was recognized.

The production of wine in Georgia in 1860 was 27,000 gallons, not in itself an impressive figure, but remarkable in comparison to the virtual absence of any production at all in 1850. In 1870, five years after the Civil War had ended, Georgia made 21,000 gallons.[83] Obviously the war did not put an end to winemaking on the scale that it had reached just before it began, but it is equally clear that the expansive and enthusiastic interest of those days had been killed. As for Charles Axt, who inspired the grape growers of Georgia, he was murdered in his bed with a hatchet in 1869; his slayer remains unknown.[84]

One interesting episode, at least, took place in Tennessee before the war. This was in Polk County, high in the hills of the extreme southeastern corner of the state. The enterprise was a sort of religious charity, yet without any distinct religious or economic ambitions, and it left so little record that even local tradition has hardly anything to say of it. Some time in the late 1840s the family of the emigrant Long Island horticulturist André Parmentier bought land in the Sylco Mountains of southeastern Tennessee, and, by 1850, had settled on it six Catholic families—about twenty people—of French, German, and Italian origin.[85] The Parmentiers, a married and an unmarried daughter, were devout Catholics, active in the lay affairs of the church, and they evidently conceived of their Tennessee settlement as a Catholic community. The place was called Vineland, or, in one account, Vinona. There, under the direction of a Monsieur Guerin, and in the midst of forests abounding in bears, panthers, and rattlesnakes, they planted vineyards of Isabella and Catawba grapes and made both white and red wines. There is also evidence that some wine, at least, was made from wild grapes. Because of the great steepness of the slopes—up to 45°—the vineyards were terraced. Polk County is credited with only 613 gallons of wine in the census of 1860, and even supposing that the Catholic communitarians of Vineland made more wine than was officially counted, they still had an industry on only the tiniest scale. What rule of life—religious or political—if any, that they lived by, we do not know. Indeed, everything about the place is unclear, except for the fact that for a decade at least, until the war dispersed it, an exotic little group of Catholics was tending native grapes and making wine for sale in the Scotch Presbyterian territory of the southern Appalachians.

Tennessee, in large part no doubt because of the unfitness of its eastern highlands for anything else, was beginning to be presented as a potential site for winegrowing. As early as 1854 the Horticultural Review noted that a Colonel James Campbell had a prosperous vineyard on the French Broad River near Knoxville

66

The symbolic—and prophetic—seal of the state of Connecticut:

laden grape vines as the amblems of divine care in the New

World. The motto may be translated as "who transplants.

sustains." (From The Public Records of the Colony of

Connecticut, 1706-1716 [1870])

and concluded that Tennessee was a good place for grapes;[86] in 1856 a Frenchman named Camuse was reported to be producing good wine in the state.[87] David Christy, the geologist, abolitionist, and journalist, published a pamphlet at Cincinnati in 1858 entitled The Culture of the Fine in the South West Alleghenies , calling attention to western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee as places peculiarly suited to the vine. But there was little experience to prove the claim. Mark Twain's luckless father owned a large property in Tennessee (Fentress County, also in the eastern part of the state), a legacy he left to his children that tormented them with false hopes of speculative profits for years. The land, Mark Twain wrote, was in "a natural wine district ... there are no vines elsewhere in America, cultivated or otherwise, that yield such grapes as grow wild here." Twain's father sent some samples to Longworth in Cincinnati, who graciously replied that "they would make as good wine as his Catawbas." But that promise was never acted on. When a buyer appeared with a scheme to settle foreigners on the land and turn it into wine country, Twain's erratic brother Orion, in a transient moment of teetotal conviction, refused to sell the land to a buyer who wished to put it to the wicked work of winegrowing. Such, at least, is the story Mark Twain tells.[88]

In 1859 and in 1860 two surveys of the wine industry appeared; one was written by the British consul in Washington, Edwin Morris Erskine, who, at the request of his government, undertook to gather statistics on the winegrowing industry in the United States. The other was contained in the national census of 1860. Together they give a picture—incomplete, indeed, but reliable within its limits—of the state of things after the first fifty years of more or less successful production in the United States, and with that picture this chapter can fitly close. In Erskine's account, which he put together in part through his own independent travel and inquiry, California was not yet a factor, though reports of its potential were be-

ginning to be heard in the eastern states. Neither was New York State, where the commercial beginnings were still too new to have made themselves visible. But, Erskine reported, the promise was almost unlimited:

About 3,000 acres are cultivated as vineyards in the state of Ohio; 500 in Kentucky; 1,000 in Indiana; 500 in Missouri; 500 in Illinois; 100 in Georgia; 300 in North Carolina; 200 in South Carolina, with every prospect of a rapid increase in all. It is calculated that at least 2,000,000 gallons of wine are now raised in the United States, the average value of which may be taken at a dollar and a half the gallon.[89]

A total of at least twenty-two of the thirty-two states then in the Union contained "vineyards of more or less promise and extent," leading Erskine to prophesy that "the culture of the vine in the United States will extend itself and improve very rapidly; and that, at no distant period, wine will be produced as cheaply and abundantly as in Europe."[90]

The figures of the 1860 census, gathered a year after Erskine's, are less expansive and no doubt nearer to the mark. The national production was put by the census-takers at just over 1,600,000 gallons. California was already yielding a significant quantity of wine—the figure given is 246,000 gallons, almost certainly too low. But the industry was still firmly centered upon Cincinnati, with its outlying provinces of Kentucky and Indiana. Kentucky made nearly 180,000 gallons, Indiana 102,000 and Ohio led all the rest with 568,000. Eleven other states, including—surprisingly—Connecticut, produced more than 20,000 gallons in 1860;[91] New York, for example, though it had gone unnoticed by Erskine, was up to 61,000 gallons. The United States, as it stood on the brink of the Civil War, was not yet making wine enough to supply a nation of wine drinkers—it does not do so even now—but it had increased its production eightfold in one decade. Mr. Erskine had the right notion of the way things were headed.