Chapter II—

Late Gothic and Early Renaissance Houses

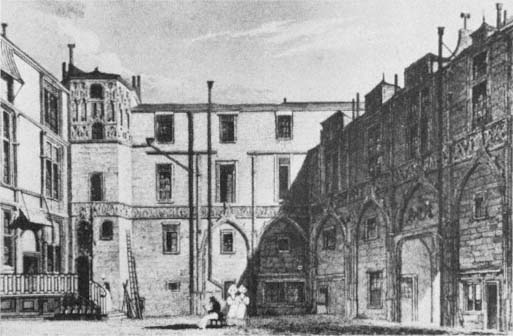

Two imposing houses, built by Princes of the Church, survive from the last quarter of the fifteenth century. These are the essential starting point for any discussion of the birth and development of the 'classic' and classical Parisian hôtel . The Hôtel des Archevêques de Sens in the east of the old city on the Right Bank was begun in 1475 and was completed by 1507 (Figs 19–23) and the Hôtel des Abbés de Cluny on the Left Bank was begun ten years later and was completed by 1510 (Figs 24–28).[1] Neither is classical, but the comparison and contrast of the two houses show decisive changes in organization which illustrate the act of conception of the 'classic' Parisian town house.

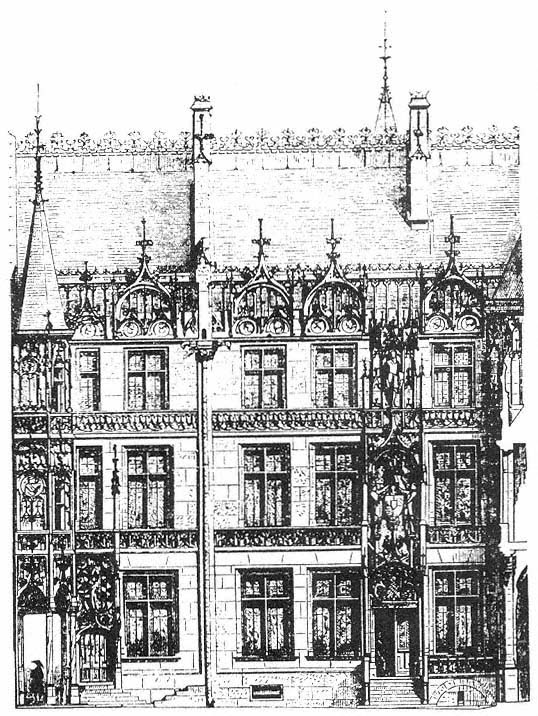

The stern appearance of the Hôtel de Sens is in keeping with our knowledge of the personality of its builder Tristan de Salazar. He was a soldier from his earliest manhood, and entered the church at the age of thirty. As a special mark of favour and gratitude for his father, Jean de Salazar's military service to the Crown, and in particular for a rescue by Jean de Salazar of the King from danger at the Battle of Montlhéry, Louis XI gave the archbishopric of Sens to Tristan de Salazar in 1474 when he was thirty-three. As a warrior and as a diplomat, Tristan de Salazar was a conspicuous figure at the Courts of Charles VIII and Louis XII, and the chroniclers and satirists of the period portray him as an ambitious, ruthless and avaricious man, with, in the words of one text, ' . . . a heart open to all evil and closed to all virtue . . .'[2] Salazar was criticized above all by contemporaries for greedily accumulating benefices and for being litigious, for the number of disputes he had with the priesthood at Sens, but Sens Cathedral was repaired and completed with large gifts from him which far exceeded the sums devoted to the building advanced by any of his immediate predecessors. An eighteenth-century guide to Paris[3] records an inscription on the Hôtel de Sens which dated from the builder's time and read 'Tristan, avec un art tout nouveau, releva ce sublime édifice, dont la vétusté consommait la ruine. Si le ciel accorde de longs jours à ce grand homme, sa mémoire sera partout célèbre dans la postérité.' Little can be said to confirm or contradict the boast of the Hôtel de Sens as built 'avec un art tout nouveau' without visual records of other important hôtels of the mid and late fifteenth century. The outstanding features of the exterior are the three pepperpot turrets on the main angles of the building, two of which flank the tall pointed arch of the main gate and its attendant

pedestrian gateway at the right. If there were openings in the ground floor on the outside, they would have been smaller and fewer than are seen today, with generous transom or mullion and transom windows to light the first and second floors. The outer elevations are crowned by heavily restored dormers on the attic with ogee pediments and fancy pinnacles, and the passerby was further informed of the power and glory of Salazar by a display of heraldry and archbishop's emblems in the tympanum of the main gate, all of which was hacked off during the Revolution, but which is recorded in an eighteenth-century drawing by Gaignières (Fig. 20). The exteriors of the south wing and the surviving portion of the east wing with the gateways are all assymmetrical, but the irregular borders of the site precluded symmetry on the outside where windows were opened where they were needed. The ensemble is given coherence by the horizontal string courses which run right round the building at first- and second-floor levels, and the entrance is given a balance by the twin pepperpot towers set

21

Hôtel de Sens. Entrance.

22

Hôtel de Sens. Stair tower.

23

Hôtel de Sens. South-western corner showing the different floor levels.

at the same height. These angle turrets were equally for prestige and defence. The curious penchant of the bourgeoisie and aristocracy for corner towers and turrets will be discussed below. The Hôtel de Sens is the last known domestic building in Paris to have serious provision made against an attack, not only with the angle turrets on the outside but also inset shoots in the point of the arch of the main gate and in the staircase tower in the courtyard for discharging boiling liquids.

The picturesque irregularity of the outside is partly a result of the shape of the site, but is also an early example of a building designed from the inside out, as commented upon by Serlio, with windows pierced where needed. In contrast, the original surviving parts of the courtyard have straight walls, and the courtyard shape as originally laid out was probably an isosceles triangle with the outer left pier of the main gate as its apex and the court front of the west wing or corps de logis as the short side of the figure. Unfortunately the exact length of the west wing is uncertain, and its relationship to and the original dispositions of the wing on the rue Figuier are unknown. The plan of the Hôtel de Sens contains many pointers to future developments with its gateways almost parallel with the corps de logis which bisects the site dividing the courtyard from the garden. The corps de logis is one room deep allowing views on to the courtyard or garden, and as its length is almost on a north/south axis, the main rooms would be lit by the milder morning and evening light as recommended by custom and later architectural writers.

We shall never know what was meant by the 'art tout nouveau' mentioned in the lost inscription, but the two most notable features of the courtyard as built were the projecting apse of the chapel near to or in the middle of the corps de logis and the stair tower, which still exists (Fig. 22). The pedigree of the large spiral projecting staircase is long and varied in French medieval domestic architecture. It gives access to all the floors both major and minor, but most interesting is its location in the Hôtel de Sens at the junction of the corps de logis and the apartments of the south wing. Such staircases often served both to give access to each of the floors of wings which might contain different numbers of levels and to act as a partition, allowing floors or wings to be locked off from the public or business activities of the house.

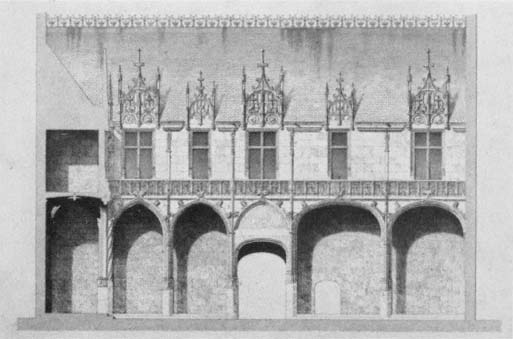

The atmosphere created by the architecture of the Hôtel de Sens is military and grave, and in comparison the Hôtel de Cluny is cheerful. The hôtel was built between 1485 and 1498,[4] whilst the beautiful gallery on the left-hand side of the courtyard was added between 1500 and 1510. Jacques d'Amboise was the seventh brother in a generation when the Amboise family were at the zenith of their power and prestige under Louis XII.[5] The youngest of the brothers, Georges, Archbishop of Rouen, was the undisputed power in the land from 1498 to his death in 1510. The patronage of all the arts and architecture by the Amboise outshone that of any other family of the late fifteenth- and the first decade of sixteenth-century France

24

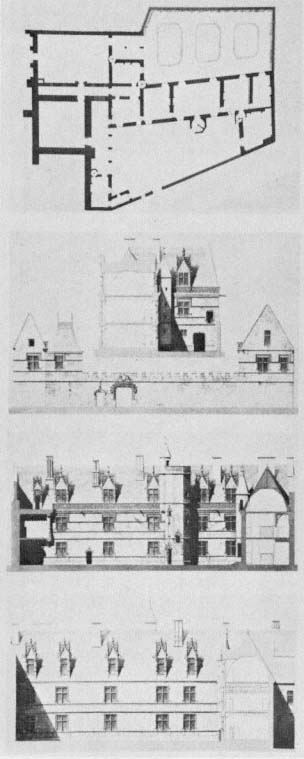

Hôtel de Cluny. Engravings from Albert Lenoir's

Statistique Monumentale de Paris of 1867.

25

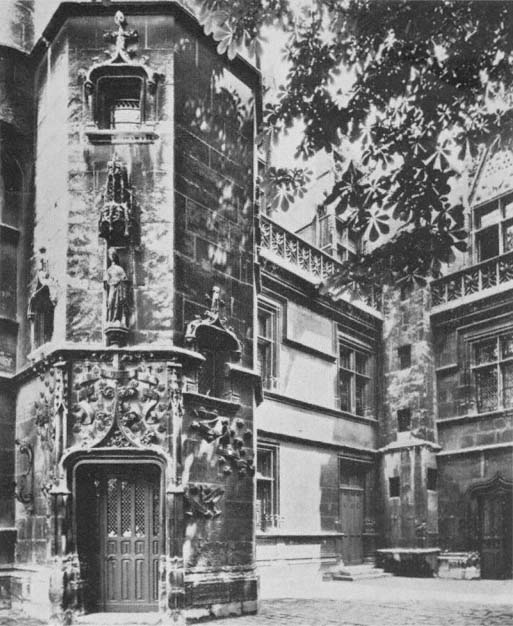

Hôtel de Cluny. Stair tower and eastern portions of the courtyard.

including that of the Crown, in its quantity, variety and modernity, and it is in the patronage of the Amboise that 'the vital steps towards Italianism' can be traced,[6] which profoundly influenced royal and aristocratic taste in painting, sculpture and architecture. At Gaillon from 1502 Georges d'Amboise rebuilt the castle in the most opulent flamboyant Gothic style

26

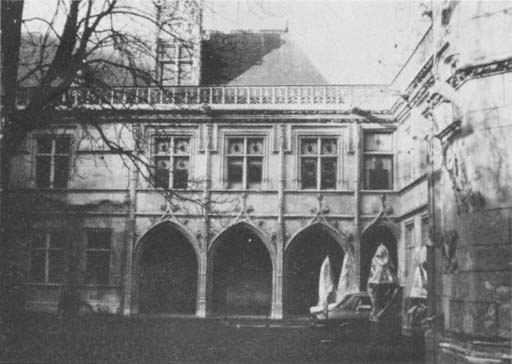

Hôtel de Cluny. Gallery.

which was succeeded by a classical style with the arrival of artists from northern Italy in 1508.[7] Gaillon is the acknowledged stylistic watershed in French architectural decoration, but Georges d'Amboise had built in Rouen one of the largest and most spectacular late Gothic domestic buildings,[8] the Palais de Justice (Fig. 29). Beside the Palais de Justice of Rouen or Gaillon, Jacques d'Amboise's Parisian hôtel looks modest in scale and in the richness and intricacy of its applied decoration.

According to Pierre de Saint-Julien, in his Mélanges paradoxalles et receuils de diverses matières pour la pluspart paradoxalles, & neantmoins vrayes . . . , published at Lyon in 1588, the Hôtel de Cluny and others of Jacques d'Amboise's building works, the repair of the Collège de Cluny close to the hôtel and the abbot's house at Cluny, were paid for out of 50,000 angelots of booty from the estates of English members of the Order of Cluny. Saint-Julien says this huge sum was accumulated within the space of three years, but adds that this should be thought neither excessive nor strange as the Head of the Order was the traditional beneficiary after the deaths of members of the Order. Such ecclesiastical benefices, notes Saint-Julien, made kings envious.

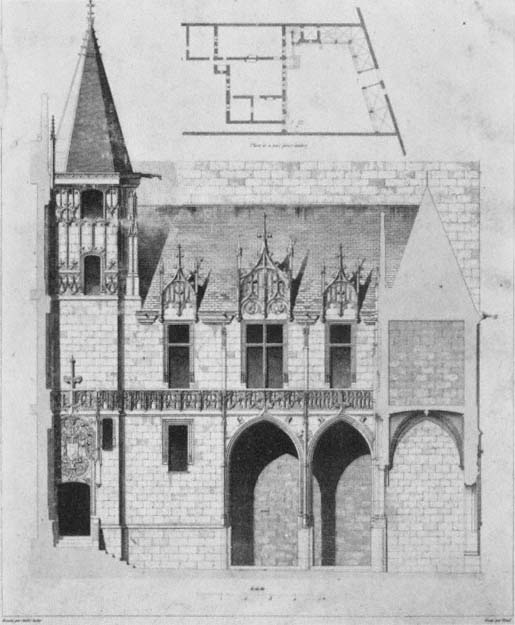

The main wing of the Hôtel de Cluny would have been built at right angles to the gallery, at the left of the court and the lateral block on the

right, had the oblique angle of the street been less pronounced. The slight obtuse angle of the junction of the corps de logis and the gallery is not obvious when passing through the gate in the crenellated screen wall to admire the decoration and clever organization of the courtyard elevations. As shown by Albert Lenoir's engravings, the three quarters of the main façade seen when passing through the gate was symmetrical with three window bays widely separated, framed on the left by the gallery and on the right by the projecting octagonal staircase. The entrance to the staircase which leads up to the largest room in the enfilade of the corps de logis is carefully aligned with the gate, and also screens the different and concentrated fenestration of the eastern quarter of the main front. The courtyard elevations are devised with what we might call 'local symmetry', with each portion designed to be seen as a complete and coherent, if not an independent composition. With the conversion of the Hôtel de Cluny into a museum during the 1850s two more pairs of windows were pierced in the front between the gallery and the stair tower, and the picturesque asymmetry which the restorers thought of as truly Gothic, has destroyed the careful balance and proportions devised by the anonymous architect of the 1480s.[9] Horizontal string courses run right round the courtyard binding all the portions of the elevation and, in contrast to the Hôtel de Sens, express the equality and consistency of height of the ground and first floors in all the wings. The richest decoration on the corps de logis and the right lateral block is reserved for the attic storey with its elaborate cornice covered with vegetable and witty animal and human caricatures, and an ornate balustrade with tall and elaborate sculptured dormers above. The gallery on the left was given special treatment with pointed arches enriched with crocketed blind ogees, and the horizontal with vertical courses which make a dense grid on the first floor. In the dormer of the gallery is the first evidence in Paris of the north Italian classicism imported to Gaillon during these years, with the square pilasters which rise at left and right of the pediment (Fig. 26). The open arcade of the gallery gave shelter for servants and stores, but its main use was as an access to the stable court which was one of the chambers of the Roman baths adjacent.

The organization of the elements in the plan of the Hôtel de Cluny is replete with traditional and forward-looking features. The entrance screen is only a token gesture of defence, and its height was calculated to allow a view from the street of the house's crown of cornice and dormers. The mounted visitor to the Hôtel de Cluny would dismount in the most spacious end of the courtyard with his horse being led away to the left, whilst he or she would walk to the prominent escalier d'honneur at the right. Projecting towers for staircases have become a theme for specialized study,[10] and apart from prominence in architectural ensembles they played an important role in the etiquette and ritual of royal and aristocratic houses, for example from the famous Louvre staircase of Charles V[11] to the Hôtel Jacques Coeur at Bourges of 1452 to 1456, the lavish Tour du Lion on the

27

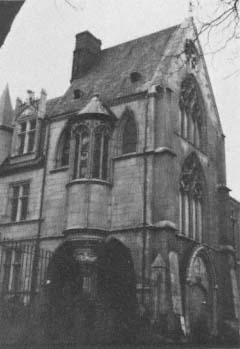

Hôtel de Cluny. Exterior of the chapel.

28

Hôtel de Cluny. Interior of the chapel.

29

The Palais de Justice of Rouen.

Château de Meillant built by Jacques d'Amboise's brother, Charles II d'Amboise, and on to the first building initiative of François I's reign at Blois of 1515 to 1524. Where a host greeted his guest would be decided upon according to the rank of the visitor. On the staircase of the Hôtel de Cluny are the arms and emblems of Jacques d'Amboise (Fig. 25) rather than on the street front chosen by Tristan de Salazar, and it gives access to ground, first and attic floors. It is not possible to be certain that the first floor contained the fine reception rooms and the private rooms of Jacques d'Amboise, but with the chapel and gallery at this level, this floor was surely the piano nobile , with the ground floor for guest rooms and offices, with service functions in the ground floor of the right lateral block. The staircase of the house was carefully placed on the façade to give access, but also to mark a partition between the public and private areas of the building, and on this principle, seen in other houses, all the rooms to the right of the escalier d'honneur should have been private apartments.

The chapel of the Hôtel de Cluny is the only feature of the interior to survive, although even it is not intact. In plan, the chapel is almost square, with a central pillar supporting elaborate flamboyant rib vaults (Fig 28). In the upper tier of the walls are intricately carved canopied niches where there were statues of members of the Amboise family instead of saints or martyrs, but private chapels or family chapels in churches were often used

to express dynastic pride with inscriptions, paintings or sculpture.[12] Cardinal's hats decorated the walls above the doors of the enfilade of the corps de logis , and as completed for Jacques d'Amboise the house must have been as full of family imagery inside, as outside. The wealth and taste of the Amboise are displayed unequivocally in the Hôtel de Cluny but it did not remain with the family as it was built for the Order, and was leased by them from Jacques d'Amboise's death in 1516 up to the Revolution, and provided a healthy income. The Venetian ambassador reported in 1577 that ' . . . [Parisian hôtels ] are almost always rented furnished, by the day or by the month; for the concierges whom we might call the estate agents for houses and palaces, find it unwise to do otherwise for fear of their master's sudden return to Court. When that happens one has to decamp quickly, above all when it is the house of a great lord. This has happened during my own time here to the Papal Nuncio Salviati, who was forced to move three times within the space of two months.' The Hôtel de Cluny had more considerate landlords for a long line of illustrious lessees beginning with Louis XII's widow Mary of England, and it was here in the next century that Mazarin first stayed in the French capital.

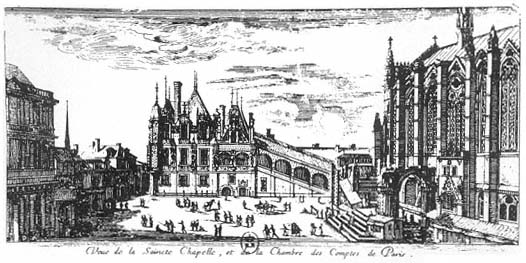

Only a small group of interesting buildings are recorded and can be described from the reign of Louis XII (1498 to 1515) but each of this group of two or possibly three buildings is of exceptional quality, the Hôtel le Gendre, enlarged and embellished around 1506 on the rue des Bourdonnais to the north-east of the Louvre in the 'quartier des Halles' (Figs 30–37), the Chambre des Comptes begun in 1504 which stood beside the Sainte-Chapelle on the Ile de la Cité (Fig. 38), and to these two might be added the mysterious and undatable Hôtel des Ursins which was once a landmark of the north side of the Ile de la Cité opposite the place de Grève and the Hôtel de Ville (Figs 40–43).

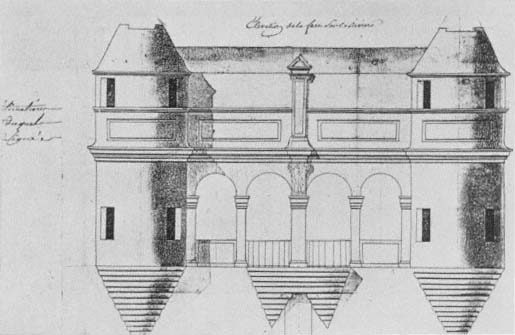

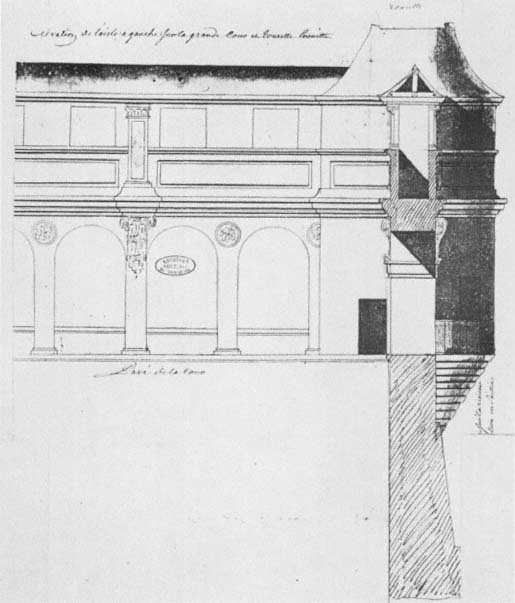

The demolition of the Hôtel le Gendre in 1841 might have obliterated all trace of a special building in the history of Parisian architecture, but the announcement of its imminent destruction provoked a fervent outcry from architects and antiquarians led by Viollet-le-Duc, which did not succeed in saving the building, but led to many of its decorative elements being preserved, and to reconstructions of its original appearance being made.[13] Romantic lithographers as much as antiquarians admired the jaded opulence of the house, but Viollet-le-Duc and Albert Lenoir studied the building, to publish reconstructions which remain the most vivid record of a lost masterpiece. Records of the Hôtel le Gendre are of exceptional value and significance because it is the last important hôtel whose plan and whose elevations are known and can be studied in detail, before a gap in our knowledge which extends to the mid 1540s. At least a quarter of a century of Paris' domestic architecture remains obscure, with only a small number of interesting buildings known from seventeenth- and eighteenth-century plans.

Pierre le Gendre (c. 1465–1524) was one of four 'Trésoriers de France'

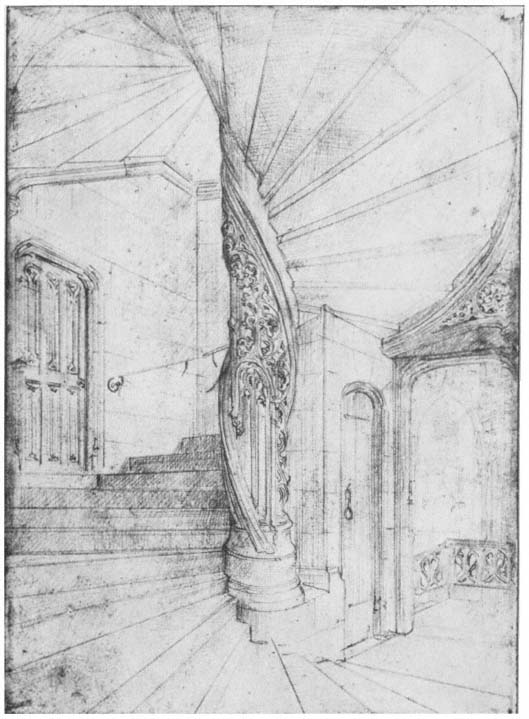

30

Hôtel Le Gendre. View of the north side of the courtyard about 1840.

and a rich and well-connected royal servant. The inventory of the contents of his house in the rue des Bourdonnais and of his country properties covers 491 folios which list about 2,250 objects, and is a valuable social document which describes the use of each room of the house and their fittings and furniture.[14] The list of the contents of the Hôtel le Gendre covers 250 folios with descriptions and valuations of every item from expensive furniture and tapestries, wall hangings, works of art and arms, to small utilitarian items in the kitchen and stables. This inventory provides detailed proof of the role of the staircase as a means of access and of partition. Pierre le Gendre built his house both as a home and as a work place with, on a floor level below the first leg of the gallery which connects with the entrance wing, (Fig. 35), the 'comptouer des clercs' or bank for his administration and secretaries.[15] Viollet-le-Duc's plan shows no direct passage from this office to the main block other than across the stairs, and as seen in Pugin's beautiful drawing of the interior (Fig. 36), the door which led into the 'comptouer des clercs' was not on the same level as any of the floors of the main block. People with business at the house might only glimpse the door of the private apartments up another flight of the spiral from the offices.

At the time of his death le Gendre's house was packed with furniture, tapestries and objects d'art, especially the apartments of the ground and first floors of the corps de logis which were replete with luxury goods of all

31

Hôtel Le Gendre. Plan from Viollet Le Duc's

Dictionnaire de l'Architecture, tome VI.

kinds. The inventory lists numerous oak chests and caskets dispersed around the house, for the regal quantities of his clothes and other valuables. The first-floor gallery which ran from above the bank to a chapel at the far end of the entrance wing was the only part of the house left sparsely furnished with a solitary settle.[16] Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century texts on the running of households insisted on the master's obligation to see that his servants celebrated mass twice daily. The bareness of this portion of the Hôtel le Gendre suggests that the chapel in the entrance wings was for communal use, and le Gendre might have had a private oratory in the tourelle (Fig. 37).

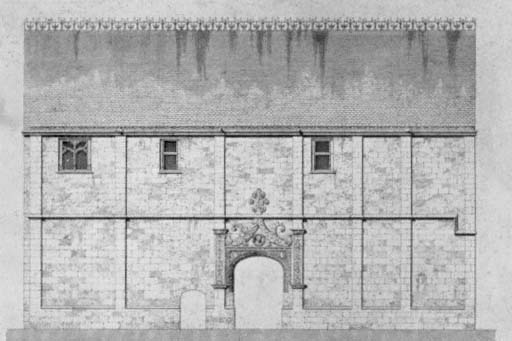

If the inventory of the Hôtel le Gendre had not survived, most of the domestic arrangements could have been divined from the plan, with the master's quarters in the middle of the site overlooking the forecourt and the garden, and having the kitchens and stables at the end of the garden with a service gate on to the rue Tirechappe. The contrast between the austerity of the street front (Fig. 32) and the opulence of the courtyard fronts made the passage from the outside the more impressive, as can still be experienced at the Hôtel de Cluny walking through the entrance screen. The gateway on to the rue des Bourdonnais was framed by a bizarre com-

32

Hôtel Le Gendre. Street front on the rue des Bourdonnais,

from Albert Lenoir's Statistique Monumentale de Paris of 1867.

33

Hôtel Le Gendre. Courtyard side of the entrance front

from Albert Lenoir's Statistique Monumentale de Paris of 1867.

34

Hôtel Le Gendre. Courtyard elevation of the corps de logis as reconstructed

by Viollet Le Duc in his Dictionnaire de l'Architecture , tome VI.

35

Hôtel Le Gendre. Elevation of the north wing linking the corps de logis with the

entrance wing, as reconstructed for Albert Lenoir's Statistique Monumentale de Paris of 1867.

36

Hôtel Le Gendre. Interior view of the staircase dividing the

corps de logis from the north wing, drawing by Pugin.

37

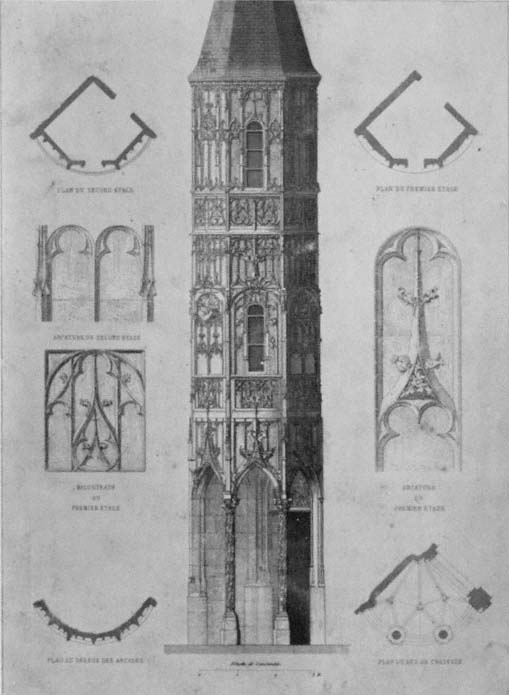

Hôtel Le Gendre. Elevation and details of the tourelle in the left-hand corner

of the courtyard, from Albert Lenoir's Statistique Monumentale de Paris of 1867.

position of raised pilasters and with a triangular arrangement of acanthus branches which faintly resemble a pediment. With its historical or portrait medallions and pilasters the entrance of the Hôtel le Gendre is the earliest truly Italianate piece of decorative design recorded in Paris, but it is more in keeping with the kind of design found on the title page of a book than with contemporary or near contemporary architecture in northern Italy or Rome.[17] The courtyard in its original condition was a showcase for the range and diversity of the skill of the Parisian master mason with decorative tracery.

Each of the six horizontal decorative layers of the tourelle (Fig. 37) has its own distinctive tracery patterns of varying complexity, with the small tiers between the floor levels and the bottom of the windows having the most intricate and dense compositions, as if they were true screens or balustrades. On the first leg of the gallery (Fig. 35) the three bays have different traceries in the horizontal band dividing the ground and first floors, and only in the dormer pediments, as reconstructed by Lenoir, is there any repetition of a pattern. Unfortunately nothing is known of the garden front; the reconstructions of portions of the courtyard published by Albert Lenoir are meticulous but are not wholly reliable when compared with the surviving fragments, and his conjectures on the roof lines and dormer pediments are reasonable and now cannot be disproved or corrected. The finesse and variety of the Hôtel le Gendre's tracery is one illustration of the vigour and inventiveness of the flamboyant Gothic style in early sixteenth-century France,[18] and with workmanship of such quality it is possible to understand how the fashion for classical decoration was slowed in Paris and the Ile de France.

The Hôtel le Gendre was not a classical house in style, but the dispositions and use of the site are those of a fully evolved 'classic' Parisian town-house plan. Many of the features described by Corrozet in his ideal house were on show at the Hôtel le Gendre with its large entrance gateway, its forecourt with rich decoration and medallions, and the siting of the corps de logis in the middle of the site facing one way on to the courtyard and the other on to a pleasant garden, which may have had the sets of antique and modern statuary imagined by Corrozet. The site of the house was long but it was not narrow with a street frontage of just under twenty-five metres in width, and allowed for a spacious court and garden. The Hôtel le Gendre was not planned to make full use of the ground as can be seen with the forecourt which was made as large as possible, the entrance and bank wings were shallow in depth and a wing was not built on the left-hand side to complete the courtyard. In houses where space was limited, kitchens would be housed in the basement of a lateral wing of the corps de logis , and horses might be stabled in the vicinity. Le Gendre had built a comprehensive set of service buildings for kitchens, stables and servants' quarters, and judging from the quantities of kitchen equipment listed in the inventory, he could have entertained lavishly in his splendid house.

38

The Chambre des Comptes. Engraving by Israel Sylvestre.

The rue des Bourdonnais was amongst the most prestigious streets in the capital in the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, as the rue de Grenelle and the rue de Varenne in the faubourg Saint-Germain were to become the addresses of the richest and royal in the eighteenth century. The Hôtel le Gendre had for neighbours the Hôtel de la Trémouïlle on its south side, and to the north the hôtel of Louis de Poncher, who was one of the four 'Trésoriers de France' with Pierre le Gendre. It is not possible to estimate whether the Hôtel le Gendre was stylistically advanced or conventional for Paris in the late 1500s, for we know nothing of the style of the houses of le Gendre's peers such as Louis de Poncher, but there can be no doubt that it was designed to impress with its opulence inside and outside, a true 'Invention Joyeuse' in the spirit of Corrozet, for whom the Gothic style was the modern style in his trio of 'Romanesque, Greek and Modern'.

The Chambre des Comptes built in 1504 is the first of a long series, which extends to the late nineteenth century, of government and municipal buildings on whose façades rich ornament and statuary celebrate an institution's standing and historical and moral traditions to the public (Fig. 38). The dormers and the projecting angle turret were covered with intricate carving, and the royal and moral kudos of the Chambre des Comptes was celebrated by the set of five statues in the niches on the first floor which showed Louis XII in company with the four Cardinal Virtues, Temperance, Prudence, Justice and Fortitude. The long arcaded-staircase ramp was used for processions and ceremonies including royal proclamations. The building was burnt out and demolished in 1737, and none of the decorations or sculpture was retained to give us a clearer idea of its style and quality than can be gleaned from Israel Sylvestre's engraving.

39

The Place de Grève and the Ile de la Cité, showing the Hôtel des Ursins

at the right of the cross's shaft. Engraving by Israel Sylvestre.

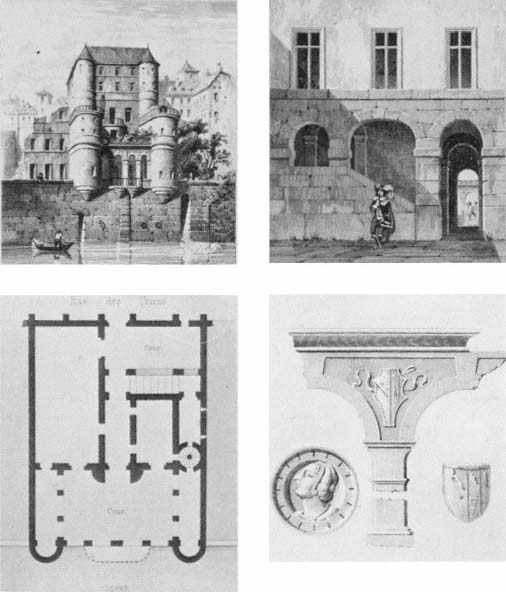

The Ile de la Cité saw very little private residential building during the sixteenth century.[19] The densely populated central section and northern side of the island, with its thirteen parishes and twenty-one places of worship,[20] had become one of the artisan and bourgeois quarters of the city before the mid fifteenth century. The sector in which stood the Hôtel des Ursins was the most notorious enclave, in and around the rue Glatigny which was popularly known as the 'Val d'Amour' with its brothels and taverns[21] (Fig. 39). This tower house is certainly fourteenth century in date and was owned if not built by a famous 'Prévôt des Marchands' Jean Jouvenal des Ursins (1360–1431).[22] Albert Lenoir's reconstruction of the house seen from the river is full of questionable details and is little more than a romantic evocation of a prominent feature of the cityscape, which disappeared about 1769, seen in Sylvestre's engraving (Figs 39–40) and in every painting showing the north side of the Ile de la Cité of the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries in the Musée Carnavalet.[23] The sixteenth- and seventeeth-century paintings agree in showing a tall square tower with full height round-angle turrets, but the paintings show an arcaded loggia below the roof that would have been an early sixteenth-century addition in the style of the terrace arcades shown by Lenoir and in survey drawings of 1760 in the Archives Nationales (Figs 41–43). The top two floors seen in Lenoir's vignette could be the result of a mutilation of the elevation in the eighteenth century, for the house is known to have been split up for multiple occupancy by the mid eighteenth century.

40

Hôtel des Ursins. Reconstruction engravings from

Albert Lenoir's Statistique Monumentale de Paris of 1867.

The date of the architecture of the terrace cannot be fixed, but the detail of a spandrel from the arcade facing the river published by Lenoir shows that it was in an unadulterated Italian style, unlike any French building of the first half of the sixteenth century. The case for the terrace arcades of the Hôtel des Ursins being an early and direct import, dating no later than 1520, is supported by the character of the medallion shown by Lenoir which resembles those of the Hôtel le Gendre. A shallow cutting into the

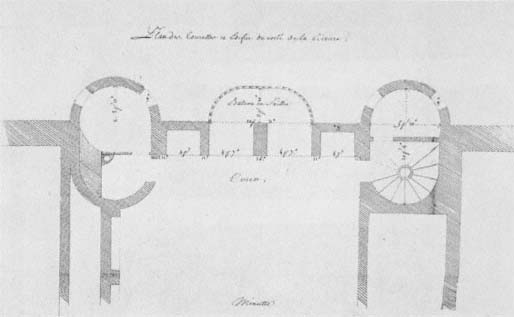

41

Hôtel des Ursins. Terrace front, an eighteenth-century survey drawing.

spandrels left a continuous moulding around the arches which is used to express a key stone at the top of each arch. The clarity and elegance of these Doric arcades made a strange contrast to the solid defensive corner turrets from an earlier building phase, and to the keep which would have excluded sunlight from the terrace. Without an exact dating for the terrace arcades, it is not possible to say which of the early sixteenth-century owners of the house was responsible for this precocious stylistic alteration. The addition of the suffix 'des Ursins' to the family name of Jouvenal came about in the early fifteenth century as a deliberate and bogus attempt to link the Jouvenals with one of the oldest families of Rome, the Orsini.[24] The pure Italian terrace might be the result of a member of the family celebrating this claim in architectural form more than a hundred years after these pretensions are first recorded. The Italian coat of arms depicted by Lenoir in one of the spandrels is not an Orsini coat of arms, but more closely resembles the arms of the noble Venetian family of Foscarini, but this heraldic signature on the building has not been deciphered. From before the beginning of the seventeenth century the Hôtel des Ursins was in decline, or 'in the hands of others' to use Corrozet's phrase, and only one event of interest took place there on the 30 May 1677 when Racine, who had lodgings in the building, agreed on the terms of his marriage contract.[25]

42

Hôtel des Ursins. Section of the terrace, an eighteenth-century survey drawing.

The reign of François I from 1515 to 1547 was a great age of country house building in the Loire Valley during its first half, and in the Ile de France during the second half, and the story of developments in classical styles under François I has to be told using examples from provincial cities and of country houses.

43

Hôtel des Ursins. Plan of the terrace, an eighteenth-century survey drawing.

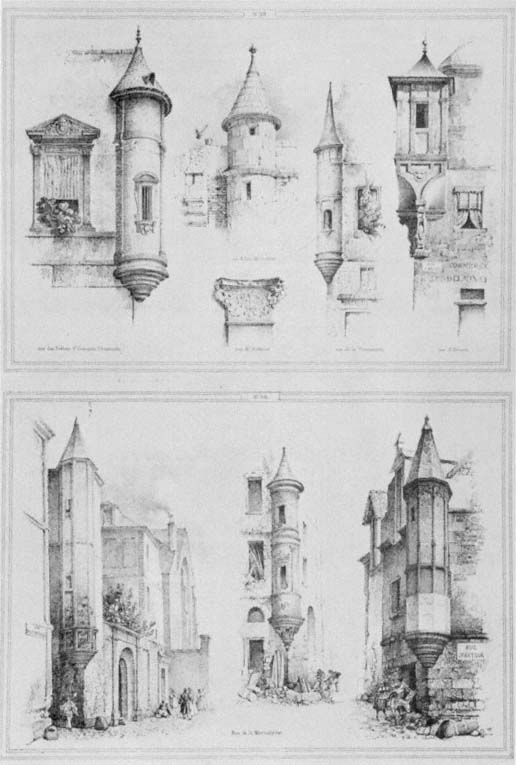

The transition from the flamboyant Gothic style to the fashion for classical motifs can be illustrated by the decoration of angle turrets, in which Paris was once rich but now is poor.[26] These expensive appendages, which required specialized knowledge of geometry in a master mason, were in medieval times considered as symbols of status for a monarch only,[27] but by the sixteenth century the affluent were seeking permission from the Parlement de Paris to add angle turrets to their houses as public statements of their civic and personal pride. The turret of the Hôtel Jean d'Hérouet is the only survivor in a Gothic style, and is thought to date from the reign of Louis XII,[28] (Fig 44), and like that of the Chambre des Comptes (Fig 38) spans two storeys and is octagonal. The elaborate blind tracery on this middle-sized private house can only be compared to the Hôtel le Gendre, where on the courtyard tourelle the patterning was more intricate. It has been claimed that the Renaissance was the only architectural revolution which did not bring with it any technical changes or reforms.[29] The idea has its faults, but on Parisian angle turrets, whether round, square or octagonal, a variety of Italianate detail displaced the Gothic and produced some curious effects without any innovations in engineering. The proportions of a correctly-drawn pilaster were not suited to a tall narrow angle-turret, and the resulting distortions can be seen in two lost examples on the rue des Prêtes Saint-Germain l'Auxerrois (Fig. 45 top left) and on the rue de la Mortellerie (Fig 45 bottom centre) both of

44

Hôtel d'Herouet. Present condition.

45

Corner turrets of the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries,

from L. T. Turpin De Crissé's Souvenirs du Vieux Paris of 1836.

46

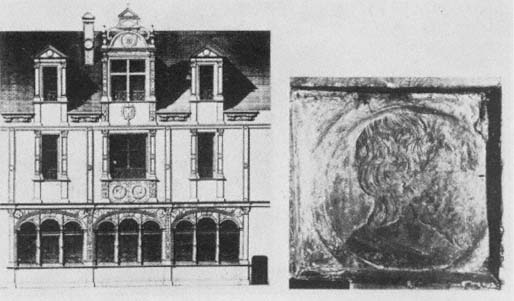

Hôtel de Neufville Villeroy, rue des Poulies.

Seventeenth-century plan.

which must have dated from the early years of François I. The corner turret of the Hôtel des Abbés de Fécamp survives (Fig. 45 bottom left) and was once decorated with royal lilies and salamander of François I,[30] but here no attempt was made on the elongated surfaces to graft classical detail. Inside, this turret there was in Lenoir's day magnificent inlaid panelling, and such luxurious fittings show that a feature which was originally for a house's defence, a place from which to watch the street, had become a place for privacy and comfort.[31] These sanctums, like an Italian 'studiolo', might have been the only truly private place for the master of a busy household. Jean de Vignolles, a notary and Royal secretary, applied to the Parlement de Paris in 1533 for permission to build a projecting angle turret on his house at the corner of the rue Saint-Denis and the Aubry-le-Boucher opposite the future Fontaine des Innocents, and he described his proposal in patriotic terms, ' . . . une tourelle triomphant, à l'antique, ymagée du roy et autres images, à la grande décoration et honnesté de la ville', for which permission was granted.[32]

Pierre le Gendre died without children, and his fortune passed to the Neufville Villeroy family,[33] which provided three generations of secretaries of state to the Valois Kings.[34] Le Gendre's beneficiary was his nephew, Nicolas I de Neufville-Villeroy, who had built a spacious house

within the dense 'quartier des Halles' on the rue des Poulies, on which building was begun before 1520 and continued throughout the reign of François I.[35] Nothing is known of the Hôtel de Neufville-Villeroy's elevations, but the plan alone is of outstanding importance in the sparse architectural history of Paris before the 1540s (Fig. 46). From the late seventeenth-century plan, where the house appears as the 'Hôtel de Longueville', the 'hôtel' appears with all its later additions, but the enfilade of the main block and the arcaded gallery at right angles to it on the left of the courtyard are amongst the original portions. The mentality behind the planning of the Hôtel Neufville-Villeroy amplified and regularized the pattern set at the Hôtel de Cluny and modified for a smaller scale for Pierre le Gendre. The main staircase was the spiral in the square angle-pavilion in the left of the court, from which there was access to all levels of the main block and to the gallery, but which at ground-floor level, shown by the plan, partitioned off the agglomerate of the ancillary buildings behind. The site was irregular, but the main block was placed almost half way down the plot, beyond which was the broader regular expanse of the garden. This plan shows the hôtel in an expanded form, and we cannot be sure of the original arrangements made for stabling horses, whether they sheltered at the right-hand side of the courtyard, or at the end of the garden as at the Hôtel le Gendre, where in the late seventeenth century there were stalls for twenty-five horses, a considerable number in a town house. Our ignorance of the appearance of this house is the more unfortunate, because de Neufville was closely involved with Italian and French artists and architects during the late 1520s and 1530s in his role as superintendent of the works at the Château de Madrid in the Bois de Boulogne.[36]

The variety of classical styles current in Paris before the upsurge of building during the 1540s can be seen in engravings recording a house on the rue Saint-Paul, the Hôtel Tyson and the imposing Hôtel d'Etampes (Figs 47–49) none of which can be accurately dated, and whose building histories are unknown. The curious hybrid decoration of candelabra pilasters, medallions and vegetable motifs of the house on the rue Saint-Paul, is a kind of ornament more usually found on furniture and on altarpiece frames.[37] Few buildings of this size or style are known, but it is comparable in scale and in many details of its decoration to a house built by Nicolas Chabouillé at Moret, which is dated to the years 1515–1525.[38] If the house on the rue Saint-Paul was as early as 1525, it predates the major transformation of the area in which it stood, the lotissement of the Hôtel Saint-Pol. The Hôtel Tyson in the 'quartier des Halles' was built shortly before 1531[39] and is curious in having Gothic decoration on its angle turret (Fig. 45 bottom right) and Renaissance decoration on the main body of the house, the most elaborate relief work being reserved for the dormers (Fig. 48). This substantial house is the only known Parisian example of the use of the old and the new style together, but there must have been others.

The Hôtel d'Etampes stood in a prominent position on the Left Bank

47

House, 27 rue Saint-Paul. Reconstruction engraving of1870, and a surviving detail.

48

Hôtel Tyson. Engraving of its condition in 1830 by Martial Potémont.

49

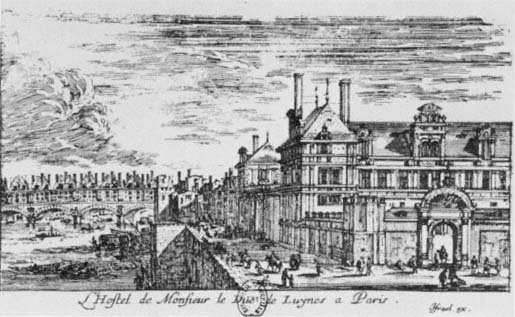

Hôtel d'Etampes (later de Luynes). View from the west by Israel Sylvestre.

opposite the Ile de la Cité just west of the Pont Notre-Dame (Fig. 49). It was demolished about 1670, and no early documents concerning it have been found in the archives, no plan has come to light, and only one partial view of it from a distance shows its elaborate classical elevations.[40] François I's most enduring mistress, Anne Pisseleu, Duchesse d'Etampes, might have commissioned the design of the building, but it was built on a site given by the King and certainly with monies from his purse, for she was both 'la plus belle des savantes, et la plus savante des belles' and avaricious.[41] The engraving shows a long corps de logis with an angle pavilion facing a walled courtyard entered by a monumental pilastered and pedimented gateway. The shell in the curved pediment might have been intended as a symbol of Venus, an amusing landmark announcing the residence of the most favoured Royal mistress.[42] A plan would show the extent of an exceptionally large house and might make possible a reconstruction drawing as has been done for a group of later lost or mutilated hôtels . The engraving shows two pavilions on the quayside connected by a tall screen wall, behind which must have been a second courtyard. It would be interesting to know if the second court was the main court, or whether the furthest angle pavilion was built to make a symmetrical composition of the river front, and abutted on to service buildings or stables, rather than a wing of the scale of that shown in the engraving. If the engraving is reliable, the Hôtel d'Etampes had a plain

dressed stone-ground floor, separated from the first floor by a wide frieze. The piano nobile had an architecture of twin pilasters reminiscent of the François I wing at Blois, with a single pilaster at the middle below an imposing central dormer, an example of the 'concordant disharmony' in fenestration which appealed to Serlio in French domestic architecture of the 1540s and before. The prolific pasticheur Androuet du Cerceau's scheme XXII from his first Livre d'Architecture of 1559 (Fig. 14) does not have applied architectural ornament closely resembling that of the Hôtel d'Etampes shown in the engraving, but his project's scale and form make the comparison interesting. A long building one room deep with a central staircase, an enfilade leading from either side of the stairs suitable for an arrangement of presence chambers, antechamber and private apartments in the pavilions, is the plan of a house for a great personage familiar from the mid sixteenth century onwards all over northern Europe.[43]

The Hôtel d'Etampes was probably built during the 1530s under royal auspices, and would have been designed in whole or in part by a senior figure in the Royal Works from one or other of the dynasties of master masons like the Le Bretons or the Chambiges. It is possible that it should have been considered in the next chapter on 'Royal Building' where there is nothing to discuss between the proclamation of 1528 and the appointment of Lescot as architect for the Louvre in 1546.

50

Terraces on the Pont Notre-Dame. Engraving by Marot.