Planning for Fewer People

In all suburban areas, the power to regulate land use is the primary means available to direct growth, protect the tax base and property values, and preserve amenity and community character. Throughout the New York region, more restrictive zoning and building codes have been the typical suburban response to population growth. A large developer explores possibilities for tract housing in Cranbury in southern Middlesex, and quickly is faced with the rezoning of most of the township's vacant land upward to one-acre parcels. In Millburn, in Essex County, the local government examines development trends and responds with two-acre and five-acre zoning in order to "make sure that the type of township we have now will be preserved in the future."[22] In addition to increases in minimum lot sizes, suburbs seek to limit intensive and inexpensive development by requiring minimum house sizes, forbidding mass-produced housing through such devices as "no look-alike" provisions in local zoning ordinances, enacting building codes that drive up the costs of housing construction, prohibiting the construction of multiple-family dwellings, restricting the number of bedrooms in apartment units, and forbidding mobile homes.[23]

The region's richer suburbs have the most restrictive codes and the most successful development policies, but almost every suburb with vacant land has sought to maximize internal benefits by zoning for fewer people. Over the past quarter-century local planning throughout the region has become far more sensitive to the costs and benefits of residential development, in part because state and especially federal planning assistance have provided resources for professional staff and consultants. Along the region's frontier, planners teach the contrasting lessons of Westchester and Nassau to those who still harbor the "misconception that the more houses you build, the more ratables you have, and the lower your tax burden."[24] Sophisticated plans are developed to limit population, with increasing attention given to environmen-

[21] Princeton Township Planning Board, 1967 Annual Report (Princeton, 1968), p. A-3.

[22] Mayor Ralph F. Batch, quoted in the Newark News, December 21, 1965.

[23] See Michael N. Danielson, The Politics of Exclusion (New York: Columbia University Press, 1976), especially pp. 50–74; Mary Brooks, Exclusionary Zoning (Chicago: American Society of Planning Officials, 1970); and Norman Williams, Jr., and Thomas Norman, "Exclusionary Land Use Controls: The Case of Northeastern New Jersey," Syracuse Law Review 22 (1971), pp. 475–507.

[24] Donald McCoy, planning board secretary, Hopewell Borough (Mercer County), quoted in Trenton Times, August 15, 1967.

tal factors that are seen as severely constraining future development. In intensively settled suburbs like Madison Township in Middlesex, new homeowners in their tract houses soon grasped the rudiments of suburban political economy. Faced with rapidly mounting costs caused by mass development on 50-by-100-foot lots with no offsetting industrial or commercial property, Madison residents sought relief by rezoning undeveloped land for one-half and one-acre lots, so that people like themselves would no longer be able to settle in the municipality.[25]

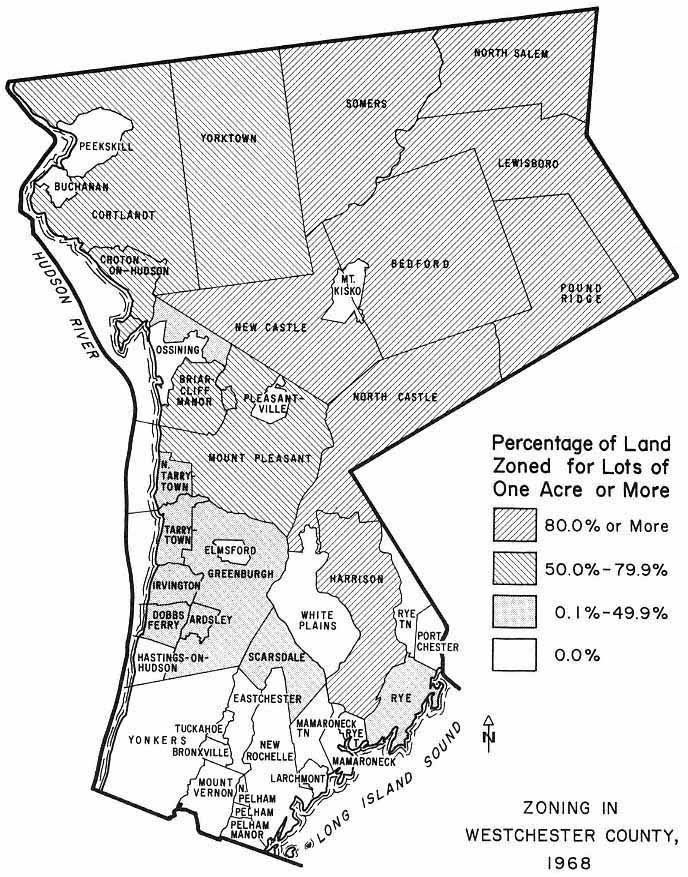

Largely as a result of these pressures in suburbs rich and poor, the average lot size in five inner- and intermediate-ring counties—Fairfield, Bergen, Middlesex, Passaic, and Westchester—more than doubled between 1950 and 1960. In 1952, Westchester was zoned for 3.2 million people; nineteen years later upzoning had reduced the county's residential capacity to 1.8 million. By 1962, two-thirds of all the vacant land in the New York region was zoned for one-half-acre or larger lots, while two-fifths of the total was reserved for parcels of one acre or more. Over half of all the land in Westchester's towns—which encompass most of the county's undeveloped acreage—was zoned for lots of two acres or more by 1968. (See Map 4.) By 1970, in the New Jersey suburban belt which encompasses Morris, Somerset, Middlesex, and Monmouth counties, over three-quarters of the undeveloped residential land was zoned for one acre or more, and houses of at least 1,200 square feet were required on 77 percent of the total acreage available for single-family dwellings.[26]

The trend toward more restrictive land-use controls in the New York region drew increasing fire in the late 1960s. Civil rights groups, fair housing organizations, labor unions, and other critics attacked the exclusion of blacks, lower-income groups, and blue-collar families from housing opportunities in the suburbs. Among the more vocal opponents of restrictive zoning are institutions with a regional perspective, such as the Regional Plan Association and the New York Times . The RPA's report on "Spread City" scores suburban land-use policies for promoting social irresponsibility, exporting costs and problems to others, wasting land, increasing the costs of public-utility systems, and undermining public transportation.[27] Similar concerns have been voiced by state officials in New Jersey, who have advocated a reversal of municipal land-use trends in the face of the state's growing housing crisis.[28]

[25] Madison Township's zoning restrictions were successfully challenged in state court in 1971 by a developer and Suburban Action Institute; see Oakwood at Madison, Inc. v. Township of Madison, 117 N.J. Super 11 (1971) and Oakwood at Madison, Inc. v. Township of Madison, 128 N.J. Super 438 (1974). During the course of the extended court fight, Madison Township changed its name to Old Bridge Township.

[26] See Regional Plan Association, Spread City, RPA Bulletin No. 100 (New York: 1962); Economic Consultants Organization, Zoning Ordinances and Administration (New York: 1970); Westchester County Department of Planning, Interim Report 6, Residential Analysis for Westchester County, New York (White Plains, N.Y.: 1970), pp. 8–15; and State of New Jersey, Department of Community Affairs, Division of State and Regional Planning, Land Use Regulation: The Residential Land Supply (Trenton: 1972), pp. 14–16.

[27] See Regional Plan Association, Spread City, passim .

[28] See State of New Jersey, Department of Conservation and Economic Development, Division of State and Regional Planning, The Residential Development of New Jersey: A Regional Approach (Trenton: 1964); State of New Jersey, Governor, A Blueprint for Housing in New Jersey, A Special Message to the Legislature by William T. Cahill, Governor of New Jersey (December 7, 1970); and State of New Jersey, Governor, First Annual Message to the Legislature, Brendan Byrne, Gover-nor of New Jersey (January 14, 1975). Efforts by the Cahill and Byrne administrations to ease suburban zoning restrictions are discussed in Chapter Five, as are earlier proposals made during the administration of Governor Richard J. Hughes.

Map 4

Zoning in Westchester county, 1968

Vigorous support for these proposals comes from most of the region's residential developers, who have little love for the land-use practices of the "tight little islands with a stay-out sign for home builders [and which] are unconcerned about the population explosion."[29]

[29] John B. O'Hara, President, New Jersey State Home Builders Association, quoted in John W. Kempson, "Zoning Called Bar to Full Land Use," Newark News, March 4, 1965.

But this criticism has little direct impact on the policies of suburban governments. While pockets of local opposition to fiscal zoning are found in the region, particularly in suburbs with more heterogeneous populations, those who favor liberalization rarely succeed in their encounters with local planning or government bodies. In Princeton Township, for instance, liberal Democrats, civil rights groups, teachers, and moderate-income members of the ItalianAmerican Federation sought in vain during the 1960s to alter restrictive landuse policies in order to foster a balanced and diversified community. Among the opponents of liberalized zoning in 1966 were two successful candidates for local office, one of whom did "not see the point of providing housing for anybody and everybody," while the other "certainly [didn't] want this Statue of Liberty in Princeton."[30] During the same year, a campaign to rezone a large area of Greenwich downward to one-half-acre lots failed, despite the support of local firemen, nurses, post-office employees, and some owners of large parcels of undeveloped land. Defenders of four-acre zoning insisted that their resistance to change had "nothing to do with racial or religious factors. It's just economics. It's like going into Tiffany and demanding a ring for $12.50. Tiffany doesn't have rings for $12.50. Well, Greenwich is like Tiffany."[31]

Local government agencies like Princeton's planning board and Greenwich's zoning commission successfully resist pressures for more intensive land use because they are responsive to the desires of the majority of their constituents. Opposed to rezoning in Greenwich in 1966 were thirty-four local organizations, ranging from taxpayer groups and neighborhood associations to garden clubs. "In Greenwich," observed a landowner who favored change in local four-acre zoning, "no one can get elected unless he swears on the Bible, under the tree at midnight, and with a blood oath to uphold zoning."[32] Once in office, such officials are strongly guided by community sentiment and local self-interest. As the chairman of Princeton's planning board explained in 1966: "Unless there is a groundswell or sentiment for high-density zoning, or through court action, Princeton will remain a residential town of relatively large home lots. . . . [The people of Princeton] would rather live in a low-density suburban area than in a town or city. . . . "[33] As the 1970s came to a close, no groundswell had yet appeared in the vast majority of the region's newer and richer suburbs, most of whose residents continued to prefer spacious zoning.