Chapter II

The History and Isolation of the Lese

"That is the way we Lese are. We want to be alone. Every house to itself."

—A Lese woman commenting on the infrequency of Lese interactions with the neighboring Budu farmers

Discoveries are inseparable from the roads we take to find them. Traveling south from the town of Isiro, across the forest-savanna border, through seemingly endless stretches of green, and into the heart of the Ituri rain forest, one is aware of the dilapidated north-south road as an encumbrance—a barrier to overcome, rather than an integral part of the local human landscape. Many Zairians who live with the road do not think of it as their own; it belongs to the tourists, missionaries, expatriate traders, and scientists, for whom, as some Zairians say, it was originally intended. The foreigners are the ones who have always depended upon it for commerce and mobility. For me, the road was a lifeline that linked me to what I perceived to be "the outside world," and I endowed the road with enormous personal meaning and significance. I tended, therefore, to unwittingly think of the road not only as the route of foreigners, but also as the anthropologists' footing, as an extension of myself. It was many months before I began to conceive of the road as an important element in the everyday lives of the people of Malembi.

The road alongside which the Lese of Malembi currently live is for them a symbol both of isolation and of contact; it constitutes both the limits and the possibilities of isolation. To some extent, Lese and Efe interaction with neighboring societies, and with urban or plantation systems, has been extensive or slight depending upon the condition of the road. In the 1930s, before the road was built, the Lese lived in interaction with a number of different groups, such as the Budu and the

Mamvu, but interaction must have been infrequent. Even within Lese areas, villages were situated as far as fifteen kilometers apart. During the 1940s, the Belgian administration displaced the Lese from their deep forest villages, resettled them close to where they intended to build the north-south road, and eventually forced them to construct it. By the 1950s, when Belgian colonialism reached its zenith, the north-south road was as wide as twelve meters. Trucks passed daily, going back and forth from Isiro and Mungbere to Mambasa, Epulu, and Kisangani. In those days, the trip from Isiro to Mambasa took less than five hours; from Isiro to Kisangani took just over a day.

By 1987, the road had so deteriorated that the trip to Mambasa took two days, and the trip to Kisangani sometimes took five to ten, depending on the weather and road conditions. All along the route, there are now bridges in ruin, deep holes, and trenches; long stretches are so overgrown that they are hardly passable. There are visible signs of atrophy also in the gutted buildings of the Belgian administration that now house Zairian government offices, in the disused rail lines, telephone and electrical poles, and remnants of the once lush plantations and gardens of the former European owners. At one time, Belgian and Greek entrepreneurs maintained plantations within a short walk from Malembi, and near the gardens of the Lese one sometimes finds old pipes and cement culverts blanketed in foliage.

During the rainy season, in October and November, the road is so muddy that only small motorcycles can get through. Occasionally, perhaps once or twice a month, a vehicle driven by a Catholic missionary comes along. Because of the humidity (even in the dry season at the beginning of the year) and the dense overhead curtains of plant life the road is seldom really dry. Villagers wage a constant battle to cut back the vegetation from their own paths, villages, and gardens, and the police and military continually press the villagers to clear narrow stretches of road, and to widen its borders in the hope that Land-Rovers, if there were any, could pass.

The road in a sense symbolizes what anthropologists have been gradually learning as we begin to explore historical transformations and reproductions, and place the study of social organization, kinship, or the economy, among other things, within a wider historical context. This change is a response not simply to synchronic studies but also to the old notion that communities can be studied in isolation from larger domains, such as the region, the nation, or even the international community. Epistemological changes in anthropology involve reconceptual-

izing the boundaries of what we assumed to be "closed societies," to one extent or another removed from the larger spheres of capitalism, polities, and the world system. Situating our fieldwork within historical context represents a central paradox in the practice of anthropology; the problem, as Sally Falk Moore phrased it, is that anthropology is practiced not in the world but in the local community, yet the local community exists within the world (personal communication).

If we overemphasize the importance of exogenous forces, we run the risk of viewing the communities we study as encompassed and determined by them, and of perpetuating the analytic dichotomy between the closed and open society, the traditional and the historical, the primitive and the modern (Lévi-Strauss 1976, Comaroff 1984). The north-south road of Malembi was, indeed, built by the Belgians. In the course of the road building, not only were many Lese forced to work on the road but others were made to relocate and work on plantations, missions, and in urban centers that were previously far out of their domain. But the Lese and the Efe also "constructed" the road both literally and figuratively. Many Lese, my informants tell me, welcomed the changes. Some Lese were happy to move to the roadside and engage in plantation and missionary work. Many Lese also enjoyed selling their crops for cash and receiving medical care from the missionaries. In past years, however, many Lese have sought to destroy the road and to insulate themselves from outsiders, primarily for the purposes of achieving safety and autonomy. Instead of trying to maintain the road, they have worked to help its deterioration as a way of reducing their contacts with European and neighboring groups—not only government administrators and Greek traders but also the Ngwana, Budu, Bila, and Mamvu, among others, all of whom are called ude , meaning stranger and enemy. More recently they have attempted to minimize the effects of Zairian state and regional domestic policies (especially those concerned with the value of the Zaire currency) on their local economy by participating less in local markets and wage labor. The Lese and the Efe with whom I lived from 1985 to 1987 try to interact almost exclusively with one another. More and more, owing both to their wishes for isolation and to the condition of the road (for which they are in part responsible), they are physically isolated from the missionary, urban, and agricultural systems with which they were so well acquainted before independence.

Lese men and women of all ages are ambivalent about such isolation. The villages, they say with sadness, are today much smaller than in

former years. This is due largely to a high mortality rate, and lower fertility (Ellison et al. 1986) resulting primarily from venereal disease. It is hard to determine just how prevalent sexually transmitted diseases are in the area, but gonorrhea and syphilis appear to be common among both the Lese and the Efe. In addition, AIDS, though most prevalent in the urban areas of Zaire, may soon reach the rural areas in which the Lese live. The poor condition of the road means that the Lese have less access than they would like to missionary hospitals and clinics. They also have less access to cloth and Western goods such as shoes and radios. Outside traders rarely enter the area to buy coffee or peanuts from the Lese, and since the Lese themselves show little desire to repair the road, and the Zaire government has neither the money nor the inclination to help the Ituri region, the present isolation will no doubt continue.

But isolation has its rewards in security and sanctuary. The lives of the new generation of Zairian Lese have been filled with anxiety and fear about the role of the state in their everyday lives. The Lese cite frequent imprisonment, poverty resulting from exploitation by government authorities, and the high inflation of the Zairian economy as examples of the dangers of the integration of their lives with what they call the "outside" world. The inside world of the Lese and the Efe is something to be protected and maintained, even if the insulation of that world has its costs. I cannot stress enough the importance and saliency of isolation that I found to be the case for the Lese during my fieldwork, the frequency with which the people of Malembi spoke to me about being alone (ite ), different (muamua ), and socially fragmented (ikau ). Isolation is not something of which only I am conscious, as I pursue an analysis of a social situation; this is how the Lese represented themselves to me.

The Lese of Malembi are isolated in two ways—isolated as a group, as a result of their conscious struggle for greater security and autonomy in the context of a history of oppression and peripheralization, and isolated from one another in smaller social units such as the house and the village, as a result of cultural dispositions. The deterioration of the road, the consequent loss of access to markets, and peripheralization from the centers of Zairian politics and economy forced the Lese into a larger geographical and social isolation, but cultural preference determined the internal social isolation. The tendency toward isolation in social and economic organization (a subject that forms the basis of chapters 4 and 5) cannot be underestimated. Not only the structure and

layout of Lese villages but also the beliefs in various forms of witchcraft and local prejudices against the sharing or trading of cultivated foods among themselves reinforce the larger isolation in a way quite different from the process of marginalization and peripheralization in the political economy. However, many Lese, I believe, rationalize their peripheral status in terms of the wishes for the isolation of other more local social domains; that is, although many Lese do not want to be isolated, especially from markets and medical centers, they may say that they do. One young Lese woman, commenting on the infrequency of her contacts with the Budu, a neighboring Bantu-speaking group, said, "That is the way we Lese are. We want to be alone. Every house to itself." She quite clearly confounds two different kinds of isolation—isolation in the larger political and economic context, and in the context of everyday village life—and thus draws a connection between the isolation of the Lese from other ethnic groups, and the isolation of houses from one another. She said, quoting a Lese proverb: "Pigs know each other by their noses," meaning that one should know only those with whom one is living intimately, or, more literally, those to whom one is close enough to smell.

Isolation, then, is one of the constituents of Lese identity. The Lese are, of course, not as isolated as they make themselves out to be, nor does everyone always and unequivocally hold a particular preference for contact or isolation. As we shall see, the Lese have a long history of forced labor, rubber cultivation, and relocation. More recently, and to this day, the Lese sell some cash crops to outsiders and sometimes work as wage laborers at plantations so that they can buy Western goods. Many Lese have also enjoyed occasional friendships with missionaries and the various scientists, including anthropologists, who have lived in the area over the years. Moreover, they continue to be subject to harassment by state officials. Yet the Lese of Malembi insist that they are isolated. Such is the ambivalence that characterizes the Lese within their historical predicament and allows the young woman cited above to overlook the distinction between these two parallel processes of isolation, one imposed from outside, the other imposed from within. Marginalization has become so confounded with smaller-scale social isolation—in the idea of isolation as a general tendency—that it is an integral part of many Lese men and women's self-image.

The concern with what I have referred to as "isolation" is crucial to my representation of the Lese in this study. Recall that one of the central aims of this book is to discover just how the Lese of Malembi derive a

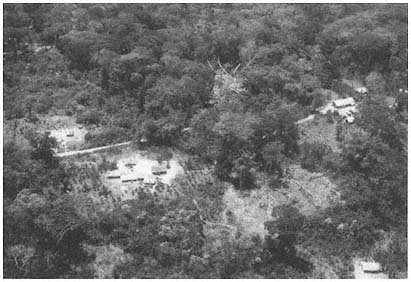

A Lese village with scattered coffee plants and a recently slashed and

burned garden. Photograph by R. R. Grinker .

sense of who they are, and where they find the cultural material to construct group boundaries and identities. Isolation has become an ethnic criterion, a way that the Lese envisage themselves in relation to their history and to the other ethnic groups with whom they have had contact.

The Lese "Chiefdoms"

More by name than by actual political organization, the farmers living at Malembi today are, officially, members of a "chiefdom." They call themselves the Lese-Dese and make up one of five Lese chiefdoms in northeastern Zaire, the others being the Lese-Karo, living from Nzaro to Mambasa, the Lese-Abfunkotu, living from Komanda to Mount Hoyo, the Lese-Otsodo, living from Watsa to Djungu, and the Lese-Mvuba, living in the vicinity of Beni, near the Ugandan border. H. Van Geluwe (1957) treats all the Lese as if they were one unified group, and the Mvuba as if they were another. G. Schweinfurth (1874), one of the first explorers to encounter the Lese, recognizes an additional group called the Lese-Obi, and P. Schebesta (1952) lumps the Mvuba, Lese, and Mamvu together as the Bvuba-Balese-Mamvu based on their lin-

guistic similarity. To my knowledge, however, those people who call themselves Lese-Obi identify themselves as a subgroup of the Lese-Abfunkotu. The Lese-Otsodo also present some confusion, since many Otsodo identify themselves as Lese-Mangutu. The Mamvu, today considered by Zairians to be a non-Lese group, live north of Malembi and Dingbo. The Lese-Dese, with whom we are concerned here, is the smallest of all the groups. They live in the Collectivité Lese-Dese , a Zairian administrative unit that includes approximately twenty-three hundred farmers, about nineteen hundred of whom are Lese-Dese, about four hundred of whom are Mamvu, Lese-Karo, or Azande, and about a thousand Efe who live close to the Lese-Dese villages.

Following Geluwe (1957), A. Merriam (1959) considers the "Mamvu-Lese" as a "culture cluster" either within itself or as a subcluster of the Mangbetu-Azande cluster (based primarily on similarities in material culture). Although the customs and the language of the Mamvu are considerably different from those of the Lese-Dese and the Lese-Karo, their proximity has resulted in extensive intermarriage with the Lese, as well as the mutual exchange of language and ideas. Vansina (1990a), using A. Vorbichler's figure of a 93 percent correspondence between the Mamvu and Lese-Abfunkotu languages (Vorbichler 1971), suggests that the split between the Mamvu and the Lese groups occurred as recently as A.D. 1720. He points out that in the first centuries A.D. , several diverse groups of farmers and herders made their way into the rain forest from nearly every direction (Vansina 1990a:169). However, historians and linguists who have looked into the question of dating the arrival of the Lese distinguish the Lese from the early wave of immigrants. The immigrants included speakers of three main language families: Bantu, central Sudanic, and Ubangian; the Lese most likely derive from, or were associated with, the Sudanic speakers.

I refer to the Sudanic Lese language as "Lese," and the language as spoken by the Efe, "Efe." I have purposely dropped the prefix "Ki-," used by many scholars (e.g., Schebesta 1933; Turnbull 1965b; Bailey 1985) to refer to the languages of northeastern Zaire because "Ki-" is a prefix for Bantu rather than Sudanic languages and should therefore not appear with "Lese" or "Efe."[1]

According to the historian and administrator M. Baltus (1949), the various Lese groups before colonization classified themselves into four

[1] Readers interested in the morphology of Lese and related languages can refer to Harries 1956 and Vorbichler 1971.

divisions: the Lese-Karo, the Maro, the Masa, and the Lese-Dese. Baltus believed that, as early as the seventeenth century, the Lese were situated north of their present location, in the Uele and Bomokande River area, and that, in the nineteenth century, as a result of Zande and Mangbetu expansion, they were pushed further south. Whether or not the Lese were actually affected by Zande and Mangbetu invasions, we do know that the Lese were living with the Efe, and living within or near the Ituri rain forest, at that time (Keim 1979). The Lese themselves say that they come from a large mountain called Menda, from which all the "black people" of Africa originated. After arguments over sharing fruit, each group went its own way, the Budu traveling to Wamba, and the Mamvu and the various Lese groups traveling southeast toward the Nepoko River.

We do not know where Mount Menda is located; we cannot even be sure that such a mountain exists outside of legend. Most Lese I interviewed, however, are confident that their ancestors emigrated from the north, and Mount Menda may therefore be a metaphoric representation of north. Paul Joset (1949), another historian and administrator, thought the Lese could have traveled south to the Ituri from the Uele/ Bomokande region, or, just as possibly, could have come from the Ruwenzori mountain area far to the east and gradually moved west across the Semliki River, from what is now western Uganda.

There is some support for this latter theory. For one thing, the Lese-Mvuba (they appear as "Mbuba" or "Bambuba" in Joset 1949) live today not far from the Semliki, the town of Beni (close to the Uganda-Zaire border), and Lake Mobutu (formerly Lake Edward, on the Uganda-Zaire border) and form part of a larger ethnic group called the Amba. Also, some elderly Lese-Dese informants told me that despite the many people who believe Mount Menda is in the north, it is actually located in the savanna to the southeast of the Ituri forest. Furthermore, Baltus (1949) says that his Lese-Mvuba informants talked of migrating from a great lake (there are no great lakes in the Uele region), following the Mamvu and Lese-Dese across the savanna. There is also support for the Lese legend of migration from a mountain in the fact that, whereas there are few mountains in the Uele or Ituri regions, the area around the Semliki is quite mountainous. In addition, the Lese-Dese language contains words for birds and mammals that live only outside the rain forest, such as hippopotami and lions, large populations of which live in the valley of the Semliki River. Joset writes:

The Bambuba [Mvuba] are blood brothers of the Walese, and of the Mamvu. They seem to have been the rear-guard of the migration; the

Mamvu, followed by the Walese, preceded them. . . . According to the commissioner of the Absil district, the Bambuba came from Kitara, in Uganda, by way of Mukeve, to the north of Ruwenzori. In the course of their migrations, they settled in MUHULUNI [sic; Uganda], near the border, then settled in the Abwanza region (currently inhabited by the Watalinga). Under the pressure of the Watalinga, who also came from the east, the Bambuba crossed the Semliki River and settled on its banks.

Sharing the same ethnic and racial characteristics, the Mamvu-Walese-Bambuba also share the same linguistic characteristics. (1949:5, my translation)

The linguistic evidence may be quite unreliable, of course. If the Lese came from the north and traveled through the forest south to the Semliki, and then moved back into the forest, they could have been familiar with mammals in a transitory way. Many Lese groups who live near the forest-savanna ecotone have had contact with a variety of savanna populations, so that words of savanna origin were introduced into the vocabulary at various points in history. Joset, on the other hand, says that the various Lese groups, "the warriors of the forest," as he calls them, did not like the savanna and searched for forest land. He says that the Lese, after living for some time at the edge of a series of mountains, were afflicted with severe hunger. They dispersed and looked for hospitable territory.

The Walese left Mount Ami, stopped for a short time at Mount Sawa, and settled on Mount Mulabu, in the middle of the forest. They planted bananas there, proof of a prolonged stay.

Several years later there was a great famine that dispersed the Walese. Each family split off from the group, going its separate way, seeking hospitable soil; this would be the last stage of their migration. (Joset 1949:5, my translation)

The First Citizens

Geluwe (1957), a Belgian museum worker who had never been to Africa, but nonetheless assembled reports of explorers, missionaries, and Belgian territorial administrators into a volume on the Lese and Mamvu peoples, agrees with Joset that the Lese came to the forest and discovered the Pygmies, whom she refers to as the ancient inhabitants of the Ituri forest. The Pygmies are, in fact, officially designated in Zaire as "Premier Citoyens" (first citizens), a title that, in addition to lumping these culturally different groups under a single category, accords them the privilege of not paying taxes. Both Joset and Geluwe state with confidence that the Lese represent the first non-Pygmy arrival to the forest.

There is, of course, little evidence to indicate how long the various Pygmy groups have lived in the Ituri, and Vorbichler's dates, based on linguistic evidence, are far from conclusive. If, as some recent ecological data suggest, no hunter-gatherer group has ever lived in a rain forest environment independent of agriculture (Headland and Reid 1989; Bailey et al. 1989; Bailey and Peacock 1989), it may well be that the Pygmies entered the Ituri at the same time or later than farming communities, and the Lese-Efe relationship may therefore be of very recent origin.

The history of the relation between the various Pygmy groups is as unclear as the history of the relation between the Lese and the Efe. The short-statured hunter-gatherers who live with the Lese and the Mamvu in the northern Ituri forest call themselves the Efe. They distinguish themselves from three other named Pygmy groups in Zaire: the Mbuti, who live to the south of the Efe and who are associated with the Bantu-speaking agriculturalist Bila; the Sua, who live on the western border of the Ituri and are associated with the Budu, and the Aka, who live in the northwest with the Mangbetu. The members of each of these Pygmy groups generally associate with one, but sometimes more than one, group of farmers and speak a language that is mutually intelligible to the farmers. Thus, the Mbuti, who associate with the Bila, speak a language similar to KiBila, and the Efe speak a language similar to Lese. When Mbuti and Efe meet, they communicate in Swahili or Lingala.

Despite the differences in language, Schebesta sought linguistic evidence to explore earlier relationships among these disparate Pygmy populations. He intended to show, first, that there were similarities in structure between the language of the Sua and the language of the Efe, and, second, that the Sua and Efe similarly altered the languages as spoken by the farmers. For example, although the Sua and Efe languages are radically different, they both drop the sound /k / in favor of a gutteral sound; /aka / as spoken by the farmers thus becomes /a'a / in Sua or Efe, and /mpaka / becomes /mpa'a /. If Sua and Efe could be shown to be similar to one another, and yet distinct from the languages of their village counterparts, this might point to an earlier unity, linguistic or otherwise, between Pygmy groups. Turnbull furthered this line of investigation by stating that an Mbuti from any part of the Ituri can recognize , though not comprehend , any other Pygmy language. However, there are too few data to support generalizations about prior unity, and the hypotheses are fueled less by scholarly investigation than

by the assumption that foragers and farmers entered the forest independently, and that all Pygmies were at one time a single, undifferentiated cultural group.

Finally, the study of the history of the relations between the Lese and the Efe, as we shall see, is in somewhat of a muddle. Recognizing the importance of the relationship between the two groups, however, can lead to several interesting lines of research, including glottochronology (Vansina 1990a) and studies of the historical changes in Lese-Efe relations. One might well question whether the Lese sought relations with the Efe because of the demands foreigners placed upon the Lese to supply forest goods. There is strong evidence to suggest that some patron-client relations in Africa have their origin in imperial or colonial history (Turton 1986). D. Turton, for example, argues that the link between the Mursi pastoralists and Kwegu hunters and cultivators of Ethiopia was forged in recent imperial history primarily to enable the Mursi to exploit the Kwegu for ivory. As well shall see in a moment, both Arabs and Belgians demanded ivory and rubber, and the Lese were able to provide their quotas only with the help of the Efe. Establishing a point of origin for such complex relations is an endless and perhaps fruitless task. Neither this chapter nor this book attempts to answer such questions. However, future investigations must take into account the historicity of ethnicity. It is unlikely that the Lese and the Efe of today resemble those of yesterday.

Precolonial History

In any case, Baltus states that by the nineteenth century the Lese bordered the left bank of the Nepoko River, and its southern tributaries, the Uala, Afande, Mambo, and Ngaue rivers. A group of people known as the Masa followed the Lese south, settled east of the Lese-Dese on the Kero River, and would much later be incorporated into the new Lese-Dese chiefdom. The Lese-Karo, and the Maro, occupied the left bank of the upper Bomokande, as well as parts of the Nepoko, Nduye, Epulu, and Ituri rivers. Another group, the Lese-Abfunkotu, who now live southeast of Mambasa, followed the Ituri River and established themselves on what is today the Beni road. For reasons unknown to Baltus or Joset, the Lese subsequently migrated south and west from the Nepoko toward the confluence of the Biasa and Nduye rivers. The Andisopi and Andipaki phratries, which today occupy Malembi, the

site of this study, occupied the Afande and Mambo rivers. According to Baltus, Tshaminionge, a man whom the Belgians appointed chief of the Lese-Karo, believed that the Karo were for a time under the authority of the Mangbetu people, who today live far north of both the Lese-Karo and the Lese-Dese. The Mangbetu demanded that the Karo give them ivory and women as tributes, and later demanded rubber for trade with the Belgians and the Arabisés.

The Arabisés, a people of Arab-coastal Swahili origin who were first contacted by Europeans at the Congo River as early as 1870, were actively involved in slave and ivory trading, and their dominion extended throughout the eastern Congo, from Stanleyville (Kisangani) to Lake Albert (Lake Mobutu), and Lake Edward (Lake Idi Amin Dada). Sir Henry Morton Stanley encountered them on his expeditions and helped to establish an Arabisé settlement on the banks of the Ituri River at Ma Wambi. According to Baltus's informants, the Arabisés kidnapped young boys and girls from various groups for slavery, and mutilated or executed many adults. Joset notes:

Until the arrival of the Europeans, independently of their numerous internal ways, the Walese had to deal with large fights, first against the Bahema, then against the Arabisés . . .

Five or six years later [after a Hema invasion], came bands of Arabs, slave traders, under the authority of three chiefs . . . It was the first time the Walese came in contact with firearms. The Arabisés resumed, in a bloodier fashion, the massacres that Kabarega [of the BaHema] had carried out. The old men we interviewed—who were between six and ten years of age at the time of these events—asserted that the Arabs killed more than half of the male population and carried off children, livestock, ivory, and young women.(1949:7, my translation)

By the turn of the century, many Arabisés were settled at Wamba, within a day's walk of most of the Lese-Dese villages. Other Arabisés were settled at Andudu (36 km. north of Malembi), Nduye (70 km. south of Malembi), and Mambasa (120 km. south of Malembi). The arrival and penetration of the Belgians brought an end to the Arabisé violence and slave trading, but they continued other forms of trading for many decades. They were the first to engage the Lese in rubber and ivory production, and their presence can still be recognized in the names of the Lese-Dese, among whom names of Arabic origin such as Abdala and Salumu have been passed down over the generations, and in the presence of a Swahili dialect, KiNgwana, that is today the lingua franca of eastern Zaire.

Red Rubber

King Leopold's dynamite-carrying agent Henry Morton Stanley—and later, the whole colonial regime—was popularly known in the Belgian Congo as the "Bula Matari" (literally, "rock crusher"). The Belgians ruled the Congo ruthlessly and comprehensively, penetrating into Congolese societies to dominate, govern, and recruit labor from its members. Leopold II of Belgium began his large-scale exploitation soon after being given the Congo Free State as his personal property at the Berlin conference of 1885. Within five years, the Congo Free State claimed to own all natural products of the Congolese forests (Jewsiewicki 1983), and it had seized all land not "directly occupied" by the Africans. With virtually no financial assistance from his homeland, Leopold would have to seek revenues from even the most secluded of forest populations. Local farmers like the Lese, Bila, Budu, and Mamvu would eventually form the basis of the Belgian colonial economy (Jewsiewicki 1983; Young 1983; Young and Turner 1985).

At first, Leopold II was able to provide funding for colonial rule by exploiting ivory and wild rubber. Western demand for ivory had been high for a long time, and after the development of the pneumatic tire in England in the 1890s, the demand for rubber hosing and tubing spurred rubber production in the Congo. Between 1894 and 1905, the price of rubber doubled (Harms 1975). But there were several problems with rubber production, not the least being a shortage of trees. B. Jewsiewicki cites a 1908 report that shows only six rubber trees on average in one acre of Congo forest, each tree yielding only half a kilogram of rubber. At this rate, the rubber supply was nearly exhausted within a decade after production began. Production was further hampered by wasteful methods. Instead of extracting the sap carefully with small incisions, collectors cut and mutilated the trees, making them worthless for future use. By 1910, the Belgians had run out of rubber in Equateur Province, and the supply was waning in the Ituri. The flood of Southeast Asian rubber three years later was a further depressant. The serious human cost of rubber production also began to emerge, and it helped critics of the Belgian regime, especially the English, to influence Europeans of many nations to halt investments and seek goods elsewhere (see Morel 1906). Jewsiewicki sums up:

During the Leopoldian era in Zaire history, only 10 percent of income came directly from the Crown domains, the profit from which was mostly used to finance the activities of the Crown of Belgium. Rubber and ivory, which had

contributed 60 percent of the total value of exports in 1890, were responsible for 95 percent of the total in 1900. Rubber accounted for 84 percent of this figure, but in the long run the system destroyed itself by destroying its own resources of men and rubber trees.(1983:99).

All Congolese were taxed, but since money was forbidden in the Leopoldian Congo, they were "allowed" to pay their taxes with labor for the state or for concessionary companies. In some parts of the Congo, local inhabitants were therefore obligated to give rubber to Leopold's concessionary companies, as a labor tax, also called "taxes in kind" (Louis 1966:274), or the impot de cueillette . The formal quota was four kilos of dry rubber (equivalent to eight kilos of wet rubber) every two weeks for each male inhabitant. In actual practice, the Belgians extracted everything they could, and the requirement of a specific quantity of rubber was primarily a way to make the exploitation look ordered and temperate (Jan Vansina, personal communication). Those who did not meet that burden were subject to beatings, and the Arabisés apparently tried to get rubber in any way they could, including violent acts. Congolese sentries guarded the posts, and they were flogged and sometimes executed or mutilated if the villagers under their supervision did not meet the quota. While there is no accurate estimate on the number of Congolese men, women, and children executed, tortured, or mutilated between 1885 and 1906 (some estimates are as high as one million), the number must have been in the thousands.

Although historians have not documented actual methods of violence committed against inhabitants of the Ituri during the rubber collecting period, some missionary reports, and reports from intermediaries responsible for forcing the local populations to produce ivory, rubber, and other goods for the state, suggest that amputated hands were circulated as a currency to make up for shortfalls (Forbath 1977). The Congo Reform Movement in Britain, fueled by outrage at the fact that an individual could control and own such a large amount of land and people, accepted these reports of violence as accurate. For the purposes of his propaganda, E. D. Morel, the leader of the movement, called Leopold's reign the era of "red rubber," rubber stained with blood of innocent thousands. Even if the stories about amputated hands are inaccurate, the reality is that a large percentage of Congolese died as the result of violence and disease.

Oral history suggests that soon after contact with the Europeans, the great-grandparents and grandparents of the Lese of Malembi collected rubber, though whether or not this was a legal obligation is not clear.

Certainly, however, for the Lese as for all Congolese, the dwindling supply of rubber forced men to travel farther and farther from their villages, beyond the boundaries of their clans and phratries. Out of their own territories, various groups often fought violently with one another for rights to the little rubber that remained. In a letter dated June 15, 1915, D. de D. Siffer, a Belgian official, described to the district commissioner in Irumu the local inhabitants' difficulties in procuring rubber. Siffer's letter suggests strongly that the Lese inhabitants of the Nepoko region were under legal obligation to produce rubber; the obligation was, indeed, a general policy in the Belgian Congo; however, I know of no written documents stating explicitly that the Lese were forced to collect rubber. From his post among the Lese-Dese, Siffer (District du Kibali-Ituri Correspondence, 1920–37, Zone de Mambasa archives) writes of the rubber collecting activities of the "people of Nepoko," presumably the Mamvu:

Their [the WaLese's] forest is just about the last resource of the people of Nepoko. Seeking to take care of their taxes by the harvest and sale of rubber, the people of Nepoko show up in [our] area after walking for five to seven days, already poorly received because they come to exhaust the forests that the Walese would prefer to keep for themselves. They are starving and want to eat; they steal from the plantations, and the Walese have a great sense of property. Quarrels follow, arrows are shot, and there are wounded at every battle. The Walese is constantly vigilant.(my translation)

Siffer goes on to point out that in addition to the human casualties, many houses were burned and destroyed.

My Lese informants were clear in their association of the rubber collection era with a time of feuds that made travel beyond one's boundaries all the more perilous. The period seems to be a significant reference point for the Lese. Three elderly informants (two men and one woman) whom I questioned about the past, though not specifically about rubber, brought up rubber collection as one of the most important events in Lese history. I quote:

1. We were feuding, and the Europeans came and said "stop that." "Go and get rubber for us." They sold the rubber we gave to the BaNgwana [part-Arab descendants] grandfathers. Rubber, rubber, rubber. It went to the ude [Belgians]. The others called themselves Marabo (Arabisé), and their skin was red. My father called them KodoKokbo because it [KodoKokbo] is a long snake that is red, and the Marabo carried long sticks, and beat us with them. We had to give rubber, and they paid us with cups and beads, and bracelets.

2. Our great-grandfathers lived at the time of rubber. They would go out for two days, but stay only two days because they were afraid of being lost or killed. They did get lost, and when Ude-ni, my ancestor, looked for his father, and when he passed the Andisamba Efe, they shot him with an arrow, and killed him.

3. We were at war with the Maru [phratry]. Azima's father showed my father to a place where there was some rubber left. Our children followed, and went to the river to dig for crabs. Aumbu of the Maru heard the children EdiEdi and Aboreke. He knew they were the voices of children, and killed them. And so there the Maru killed us.

When these and other Lese informants discussed the period of rubber collection from the perspective of their relations with the Efe, they often remembered the period fondly, as a time when the Lese and the Efe shared their lives and food much more fully than they do today. For example, the Efe and the Lese cooperated in rubber collecting. The Efe, in fact, produced large amounts of rubber, and rubber acquisition thus became an essential part of their relationship with the Lese.[2] The Efe accompanied the Lese as guards on most of the Lese rubber-collecting expeditions and guided the Lese on lesser-known forest paths. One Lese man reported: "We lived always with our Efe. Every man cut rubber with his Efe. Every man stopped and stood with his Efe before the ude [European] to sell rubber. Everything. We did everything with the Efe." The Efe not only helped the Lese collect rubber, but in later years would protect the Lese from hunger seasons and the violence of Zairian national political strife.

Rubber was such an important item for the colonial administration that rubber markets were placed on the axis of the north-south trail that later became the road through the Lese residences; markets were also established at Nduye, and later at Biasa (only 40 km south of Malembi) and Paoni. Although the Congo rubber market essentially came to a halt after 1910, the Lese occasionally cut and sold some rubber on a voluntary basis until the 1930s. An elderly Lese man said, "Later the Dese stopped selling [rubber] at Nduye, but we sold at the Andikara clan [Biasa]. From there they started to build roads, and we sold rubber at Uetakukbo [Paoni]. They stopped getting rubber when Alambi became chief of the Lese-Dese [in1936]."

[2] In sharp contrast to the Lese situation, the Aka Pygmies of present-day Central African Republic did not engage in rubber collection, though why this was the case is not clear, especially since the Aka were the principal producers of ivory, another good demanded by Europeans (Bahuchet and Guillaume 1982:200).

Aspects of the Belgian Colonial Economy

Belgium responded to the financial crisis and to increasing criticism in Europe over the brutality of Leopold's regime by assuming control over the Congo Free State in 1908. Soon after annexation, Belgium replaced the brutal station agents and sentries with Belgian civil servants. Congolese soldiers were organized into gendarmeries, and the floggings, executions, and amputations were for the most part halted. Most of the forced labor ceased, as did the imposition of rubber and ivory quotas, and Leopold's monopoly on commerce was open to any and all investors. The Belgian administration focused its attention on two areas: mining and agriculture. By the 1920s, it was exploiting tin, gold, copper, and iron in the Congo for extensive profit, primarily in Katanga district. The new administration did not interfere with the mining concessions created by Leopold, but rather expanded them with a railway concession, and new mines were developed in previously unexploited areas of the colony—gold mines in the east and northeast, near Wamba, Watsa, and Mambasa, where the Budu and the Lese-Otsodo formed the bulk of the labor pool, and manganese mines in the south, partly as a response to the demands of American steelworks. By the 1920s, many of these towns had undergone extensive construction and landscaping. Schebesta noted that by 1933 Wamba was an administrative headquarters, had many factories and plantations, and had "broad streets lined with Coco-nut palms on either side" (1933).

From oral history, my best estimate is that the mines were within a three-day walk of the Lese-Dese villages, far enough away to allow them to escape direct incorporation into the mining industry. Mining development depended on the recruitment of huge labor pools from the hinterland of the colony, but recruitment was purposely carried out locally, within the vicinity of the mines, so as not to mix workers from different "disease zones" (Vellut 1983), and thereby, it was hoped, prevent the spread of disease; mortality rates were already a significant problem at the mines. The Belgian recruiters profited from indigenous food scarcity because hungry farmers sought to work on the mines in exchange for payment in cultivated food and dried, salted fish. Locusts and other natural catastrophes had always forced people to shift residences, and during these times of crisis many Congolese migrated to the mines, where food was more plentiful. The Lese-Dese, though no better off than most in their food supply, lived too far from the mines to get

attention from the labor recruiters, and I heard no accounts of any Lese-Dese going into the mining area for any reason.

Indirectly, however, the Lese and other more remote communities were caught up in the mining industry because the mine workers' food came from the agricultural sector, and because agriculture itself suffered from losses of labor as farmers flocked to the mines. When the wild rubber market finally collapsed, the colony needed a profitable and exportable surplus to increase revenues, as well as a surplus of food above the level of rural subsistence systems so that they could feed the miners. By World War I, the colony decreed that each villager had to devote at least 60 days to growing crops decided upon by the administration, and that failure to do so would result in fines, beatings, and imprisonment. Large plantations were established near Wamba to produce food for the miners, but these did not produce enough food for export. Until World War II, the only profitable export crop coming out of the plantations was palm oil, much of which came from palm fruits gathered by local hunters and farmers like the Lese (Young and Turner 1985).

European farmers in the Congo produced little food on their own and were nominally successful in coffee production only; Jewsiewicki (1983) notes that "the production of [other] foodstuffs thus remained in African hands, and its regional commercialization remained within the framework of a free market." European capital was channeled into the processing of cotton and palm oil, rather than into primary production. Recognizing this situation, many in the colonial administration aimed to increase indigenous production, to capitalize on what had already been established. In an attempt to form an agricultural policy, the administration founded INEAC (Institut National pour l'Etude Agronomique au Congo Beige) . The goal, never realized, was to have the Congolese develop cash crops such as cotton, palm oil, coffee, and rice, in cooperative paysannat (peasantry) collectives, and in that way stimulate an active market economy. The cooperatives succeeded in many instances, but the money was rarely returned to the farmers (Vansina, personal communication). Europeans did not support and encourage, or did not comprehend the logic of, indigenous Congolese agricultural practices (largely, subsistence-level shifting systems). The colonial administration considered these practices to be a hindrance to modernization (Wilkie 1987).

Along with agricultural development came the development of a commercial infrastructure that included, by the time of independence in 1960, some ten thousand miles of navigable waterways, three thousand

miles of rail, and eighty-five thousand miles of roads (Wilkie 1987). Infrastructural expansion affected even the most peripheral of Congolese, the Lese and the Efe. In 1941, when the Belgians decided to begin road construction, the Lese-Dese, and specifically the Andisopi and Andipaki phratries, were living near the Afande and Mambo rivers, a short distance from Wamba. The Belgian administration began recruiting Lese labor and forced the members of these phratries out of their villages and into Malembi, a new area east of Wamba where the Belgians intended to encourage Europeans to establish plantations, missionaries to build churches, and the Lese to build bridges and roads. The Belgians brought Lese men thirty to sixty kilometers from their villages to construct a north-south road through the Ituri forest, and, in 1943, forced entire Lese families to resettle at the roadside. The following statement by one of my informants gives us a sense of the authoritative and officious manner in which the Lese were relocated: "The strangers sat atop Malembi. They dug all the way from Mambasa to Mungbere. Five, ten, five, ten. Go there, come here. To the place of the Masa. Someone?! Present! Someone?! Present! Someone!? Present! They measured gardens for us, told us where to plant. Someone?! Present!" The Lese who eventually occupied Malembi were told to plant cotton, palm oil trees, rice, and coffee, and to abandon their practice of shifting residences every two or three years. Residences became much more permanent, with residence shifts of less than one kilometer's distance occurring about every seven years. Few of the Lese or other Congolese produced much coffee or cotton, in part as a resistance to the colonial administration. Some reports state that groups such as the Lese would plant crops following the orders they had been given but then never harvest them because they had not been told explicitly to do so (Jewsiewicki 1983).

Administrative Innovation and the Origins of the Lese Chiefdoms

Early in its rule, the Belgian colonial administration set out to enforce the cultivation of crops by means of the authority of officiers de police judiciare and also of a newly developed local administration consisting of African chiefs who were selected as the administrative chiefs of their various ethnic groups. In 1910, the Belgian administration introduced the first organized administration of territories in the Congo as a whole (Jan Vansina, personal communication). This was a decree that would

in time become a reality on the ground. The administration would choose one locally respected man from each ethnic group, give him a medallion, and name him chief of a "tribe" (tribu ). We do not know the process by which these chiefs were chosen, but we do know that they were recognized locally as men with large families, villages, and gardens. Each tribe constituted a chiefdom (chefferie ), even though many of these groups, such as the Lese, had never recognized a central authority within their indigenous political systems. The chief was to be the "customary head" of a "tribe." In the event that a particular society did not have such authority figures as an indigenous institution, the Belgians nonetheless asked local inhabitants to suggest a candidate. If they did not suggest one, one was chosen by the district commissioner. The position of chief was to be, ideally, that of a "former ruler who has been placed in tutelage" (I.D. 1213, Manual of the Belgian Congo , n.d.). Moreover, each village had to nominate someone for the position of a notable , or capita (headman). Capitas were to be heads of villages, men responsible for reporting to census takers the numbers of residents at villages, and for ensuring that these residents produced their quotas of cultivated foods.

The organization of the Lese into chiefdoms is curious because it occurred at a time when chiefdoms were being abolished by the thousands. R. F. Betts (in Boahen 1985) notes of the European colonization of Africa:

With the establishment of European administration, chiefs were manipulated as if they were administrative personnel who might be reposited or removed to satisfy colonial needs. Chieftaincies were abolished where considered superfluous and created where considered colonially useful. Perhaps the most striking example of this process occurred in the Belgian Congo (now Zaire) where, after 1918, the number of chefferies (kingdoms or states) was reduced from 6,095 in 1917 to 1,212 in 1938. (p. 147)

In addition, the Belgians were attempting to adopt the Lugardian model of indirect rule, which would recognize "native authorities" and limit the imposition of external or foreign structures of authority. In order to settle disputes and to tax, however, modifications in political institutions were necessary, and for the Lese this involved the invention of the chiefdom. The Lese were more than likely consolidated because they had no indigenous political organization beyond alliances of a small number of clans and had no leadership that could serve the Belgians as liaison for the Lese. The Belgian administrators had considerable difficulty in establishing organized contact and communication with the

Lese—so much, indeed, that it took fourteen years for them to carry out the 1910 decree among the Lese-Dese (Irumu District Correspondence, Zone de Mambasa Archives). Finally, on April 1, 1924, after what must have been a long series of attempts to consolidate the Lese into a chiefdom, their first chief, Mbula (Andimau clan), was "appointed" (Baltus 1949). At the same time, the Lese-Karo received their first chief, Tshaminionge, and the phratries were required to nominate notables to represent the villages in front of the chief. An informant said: "Before, everyone was the chief of his house, and we did not know the ways of the chief. They all got their medallions at Tutu-ke [today named Andudu]. Every tribe [tribu ] was asked 'who do you want to be your chief?' and then 'who do you want to be your notables? ' The first person to state an opinion became a notable ."

How these groups were organized into different chiefdoms, or whether the name "Lese-Dese" was an indigenous term to describe political units, is not known, but my informants suggest that the word "Lese" is of recent origin. They use the words "Lese," "Dese" or "Karo," to describe members of the Lese-Dese and Lese-Karo chiefdoms, and older people describe all Lese-Dese as "Andali," which is the current name of a large phratry, that is, a collection of clans tied together through intermarriage. The Andali phratry may have consisted of over two hundred pople at the time they were incorporated into the Lese chiefdom. According to Joset (1949:5), the term Andioli , meaning "the descendants of Oli," was used by the Lese-Obi to refer to all the Lese. Lese-Dese elders I interviewed assert that all Lese-Dese are Andali, and that the term means "the people [or descendants] of Ali."

One informant's rendition of the process by which the Belgians distinguished between the Lese-Dese and Lese-Karo suggests that linguistic boundaries were a significant factor for the Belgians in their construction of chiefdoms.

The Belgians said the Dese and the Karo should be one people. The Commandant called, "Tshaminionge!" "Present!" "Mbula!" "Present!" The Belgian said, "Who are you?" Mbula said, "I am Andali." Tshaminionge said, "I am Karo." The European asked Tshaminionge, "What do you call a bird?" He said "osa." Then he asked Mbula, "What do you call a bird?" He said "keli." Then they were given their medallions, but they were separated.

Whether Mbula and Tshaminionge used the terms "Andali" and "Karo" to refer to phratries, descent groups, or ethnic groups is not clear, but it is likely that the chiefs were identifying themselves by phra-

try, since that was the most inclusive level of social segmentation for which there was a word in the Lese language. Each phratry maintained a distinct way of speaking and gesturing, and still, today, the members of one phratry can be identified by their accents, tonality, and vocabulary.

The whole notion of a chiefdom as a politically, linguistically, and ethnically homogenous unit was generated by the colonial administration in its efforts to tighten its control and administration of the Ituri forest peoples. Much of the solidarity that Lese-Dese today experience in opposition to other Lese groups, such as the Lese-Karo or Lese-Mvuba, is no doubt a consequence of the Belgian administration's unification of various Lese phratries into their own form of political and administrative structure. Like colonists elsewhere, the Belgians attempted to fix and classify responses to their questions within their own categories regardless of whether or not those categories reflected indigenous social groups (Cohn 1987:206; Anderson 1991[1983]:168).

Censuses, too, may have played a significant role in fixing ethnic identity, even clan identity. According to my informants, Belgian administrators counted adult men of different clans, excluding the Efe. The vast literature on European images of the Pygmies, written mainly by explorers and missionaries, reveals that the Efe were not seen as potential workers, and, according to my Efe and Lese informants, were further dehumanized as "baboons" and "monkeys." The census takers would thus ask not only how many men were living at a particular clan's village but how many men were members of that clan, even if they were living or working elsewhere. Clan identity, indeed chiefdom identity, can be manipulated, yet the census takers demanded that people maintain (and perhaps, in some cases, invent) one specific set of identities. Censuses can often result in the invention and reification of social categories. In my own efforts to look at fertility and clan death, I replicated a 1947 census of Lese villages, and thus used the identical categories employed by the census takers. I may therefore play a part in producing identities and contributing to the ongoing legitimacy of the ethnic group, phratry, and clan as distinct categories. One can only wonder whether the Belgian denigration of the Efe as animal-like influenced the Lese's view of the Efe.

Oral history and interviews with elders do indicate that the Lese had little difficulty accepting a new identity as members of a chiefdom. Although the chiefdom introduced into Lese society a new category of social groupings more inclusive than the clan or phratry, the chiefdom

was a buffer between the village and the state, represented at first by the colonial administration, and later by Zairian police and other state officials. Thus, the government-imposed Lese officials came to be legitimated by the local populations not because they were respected as effective adjudicators or political representatives, but because they could protect the people from the government (see also Turnbull 1983a:59). Since state officials sometimes defer to the chiefs in the adjudication of criminal offenses or concerning fines imposed by the state, the people quite naturally appreciate that it is in their best interests to cultivate amiable relations with the chiefs.

Under the Belgian administration, a chief's duties were, not unlike his duties today, to collect taxes, mobilize labor for portage and road construction, and enforce the cultivation requirements. The colonial administration of the Congo was "organized into a microadministrative grid extending into the farthest village" (Young and Turner 1985), with the intention of controlling the resources of even the most isolated villages. It appointed local chiefs, chefs de localité , who would be in charge of a few hundred people at the most, and would report to the central chief. The Belgian administration appointed officials at the most local levels of the Congo. To my knowledge, only the Pygmy groups of the Belgian Congo, seminomadic and therefore elusive, uncountable, and considered by many Congolese and Belgians to be subhuman, were never organized into a chiefdom. My Lese and Efe informants report to me that officials during the colonial regime imagined the Efe to be violent and rarely ordered them to collect rubber, to become farmers, or to work on the road. Belgian censuses bear out the colonial view of the Efe; the official Belgian censuses I have seen seldom mention the Efe, and never count or include them as an available work force.

About seven pages of correspondence between territorial administrators and the commissioner of the Irumu district survived independence and the rebellions that followed. These letters attest to the fact that the Belgians had great difficulty dominating and governing the Lese, the Efe, and also the Mamvu, who sometimes lived within one or two days' walk of the Lese.[3] A 1912 correspondence stated, "Except for among the . . . [sic ] and the Walese and the Mamvu, the political situation had been 'good'." (Irumu, 17 Mars 1912, Benaets to the District Commissioner, my translation. Zone de Mambasa Archives). The same official stated that he had abandoned the Lese until he could gather more mili-

[3] Documents obtained by Robert C. Bailey in 1980.

tary support from Wamba in order to "subdue" the population. Several months later, in 1912, he reported that he was not hopeful about the possibility of dominating the Lese, and he remarked that the Lese had more interest in maintaining relations with the "Marabo"—the Lese word for the Arabisés—than they did in establishing new relations with the Belgians.

My informants contend that the Lese were more fearful of the Belgians than of any other group, that the Lese were frightened by the Belgians' "hideous" white appearance and their overt displays of force. Some Lese believed the Belgians to be the tore , or evil spirits, some of whom are said to have white faces. Many believed them to be cannibals. Why else, my informants asked me, would they kill so many people whom they did not know? The Lese tell numerous stories of Belgian cannibalism, and the chief of the Lese-Dese even pointed out to me two abandoned buildings in which the Belgians were alleged to have processed Congolese bodies for food. Some anthropologists working in the Ituri have had to differentiate themselves from the Belgians to avoid accusations of cannibalism.

The administrator wrote:

The situation is always bad, police operations have produced no results; I will soon be prepared to send an officer to Wamba, and a military operation will be led against the Walese.

. . . This region needs to be worked directly by European traders; they are the only ones who will create needs among the natives. But the Walese are still savages. They have hardly had any dealings with us; the go-betweens, rather unwilling, have always been the Arabisés from the Mavambi-Irumu route. (my translation)

We do not know how the region was eventually conquered, but Adjt. Sup. Benaets wrote on June 22, 1913, that sous-lieutenant Rultberg controlled the region, that the area was "calme," and that the inhabitants would no longer run away from colonial officials. There were likely several military sweeps in the region, stimulated in part by the difficulties of controlling the movements of local inhabitants, and in part by the fact that much of the Ituri was controlled by Arab descendants. In 1914, the Congo Oriental Compagnie (C.O.C.) was able to found a trading house near the Biasa River, an area that, according to a territorial administrator's report in 1939, was by 1924 the boundary between the chiefdoms of the Karo and the Dese. (Although most of the Lese were living far to the west of Biasa, the administrator's report suggests that many Lese-Dese were already living near Biasa, and therefore

near the site of the yet-to-be-built north-south road, and near what is today Malembi). According to an administrator, a Lieutenant Scharff, the Arabisé chiefs helped the Belgians forge more peaceful and cooperative relationships with the Lese at Biasa. In a letter dated August 5, 1914, M. Siffer wrote to Scharff and the Irumu District Commissioner that although not perfect, the situation with the Lese was improving: "La situation chez les Mamvu est très satisfaisante . . . chez les Walese, cela va moins bien" (the situation among the Mamvu is quite satisfactory . . . among the Walese things are going less well). But despite resistance, Siffer said, the Lese were "subdued" and received "whites" with hospitality.

The administrator also notes that the Lese were involved in several wars and feuds among themselves. Oral history I collected in 1987 indicates that several Lese groups suffered food shortages around the turn of the century, and, presumably with the help of their Efe, attacked groups with larger and more productive gardens. Explorer's accounts seem to bear this out: for example, a detailed illustration in Major Gaetano Casati's Ten Years in Equatoria (1891) depicts Pygmy women stealing corn from the garden of a Lese group under attack by their husbands. According to M. Siffer's official report, the "dwarfs" (Efe) were constantly attacking the Lese's neighbors, the Mamvu, in order to steal their cultivated foods. He lamented that any extra foods were either given to, or stolen by, the Efe, rather than traded at the C.O.C. post. In May of 1916, the same official wrote that the Belgians would never be the "masters of these forests" until they conquered the Efe, whom he called "Mambuti." He stressed that the individual Lese was "occupied" with his Efe trading partners "de tout son pouvoir" (in every capacity). The Lese, he noted, fed the Pygmies because they served as warriors for the villages of their Lese partners and guarded their Lese partners' houses, villages, and gardens from outside attack. The official concluded, "tous les méfaits qui secommettent [sic ] sont commis par les Mambuti" (all wrongdoing is committed by the Mambuti).

During the years 1914–20, few reports were made. Joset, however, collected some oral history from the Lese-Obi (who live to the south of the Lese-Dese) around 1916. He stated (1949) that, for the Lese, the age of rubber collecting was one of prosperity, and that during World War I, a number of Lese-Obi served near Kisangani as porters carrying ammunition. Although the Lese-Dese had little contact with the Lese-Obi, they had a good deal of contact with territorial administrators from Irumu. It is likely that some Lese-Dese men were also involved in

the ivory trade and helped to transport military goods. It seems that, by 1920, the Belgians had left the Lese-Dese alone, for a 1922 report from the territorial administrator at Andudu states that no Belgian government official had visited them in two years. After 1922 the yearly reports contain usually less than four sentences of general information, with phrases such as "situation bonne," or "situation excellente." Reports filed up to 1937 continued to state that relations between the Belgians and the Lese and Efe ran hot and cold, and that the Lese generally did not obey the laws of the colonial regime. In late 1926, the territorial administrator at Irumu noted that he was having considerable difficulty recruiting Lese-Dese and Lese-Karo men for service in the "F.P." (Force Publique , a Belgian-organized army made up of Congolese) or for work with l'Offitra , a rail/transport company with offices at Kinshasa and Matadi.

Between 1924 and 1935 there is little mention in official reports of Chief Mbula of the Lese-Dese. Most Belgian reports during this decade focus on Tshaminionge, the chief of the Lese-Karo. Tshaminionge seldom resisted colonial orders and is praised as "paternal," "accredité," and "le plus coutumier des chefs coutumiers" for his efforts to force the Lese-Karo to begin preliminary construction work on the north-south road. This is supported by Schebesta, who writes in 1933 that "Chamunonge [Tshaminionge] is a protege of the Colonial authorities, who have conferred on him numerous honours and tokens of their favour" (1933:225). There is no mention in the brief colonial reports I have seen of the murder of Chief Mbula of the Lese-Dese in 1927, and there is only one mention of his successor, Djumbu, whose name suddenly appears in the records in 1931. Even Schebesta, who stayed with Mbula for two days, wrote little about him, and stated only that "Mbula was valueless from the point of view of my research work, as no pigmies [sic ] lived anywhere nearby" (1933:225). Mbula was, for obvious reasons, regarded by the Belgians as an ineffective chief. Official correspondence describes him as lazy and uninterested in traveling to the various Lese villages to collect head taxes, and the government in fact considered finding a new man to replace him. But in October 1927, near the Mobilinga River, the Belgian problem with Mbula was resolved when Mbula was killed by one of his own policemen. The story told by my informants is that Mbula got into an argument with the policeman, Batuko—a Lese-Dese man of the Andipaki phratry—either about the way in which Batuko had allegedly mistreated an elderly Lese man named Akilau, whom he had tied up and beaten on charges of disre-

spect, or, as others say, because Mbula had seduced Batuko's wife, and Batuko had discovered them in flagrante delicto. Schebesta amplifies the story: "Mbula was shot dead some years ago by one of his policemen, whose wife he had seduced. The chief's family group speedily avenged his death. Two women inveigled the assassin into their toils, bound him, and beat him to death with cudgels" (1933:225). Baltus's version is that Batuko tried to escape to Andipaki but was caught and murdered by Lese-Dese civilians (Baltus 1949). One man told me:

They said, "if we go to the Europeans, they will leave this murderer, so we will kill him." They cut off his nose with a machete. Achakbati of Andipaki sent a letter to the district commissioner at Irumu. Who will be the new chief? Djumbu, Mbula's brother. He slept with the medallion [remained chief for] only a few years. The Europeans took it from him because he was a bad chief, and he tortured people. There was a lot of mud on this chief [he was dishonest and cruel]. They asked who will be chief? And they came with Arambi [of the Andape phratry], who received the medallion [in 1936].

Mbula's brother, Djumbu, succeeded him, but he was ousted by the Belgian administrators within one or two years in favor of a new leader, the chief Arambi. Reports in 1932 and 1933 state that a military excursion had been carried out by the Belgian administration in order to halt "illegal practices." Djumbu, Mbula's fellow clansman and successor, appears to have been involved with large-scale cultivation of marijuana (an illegal activity), which, according to the official reports, he exported from the chiefdom. Due in large part to the impact of the Depression, there were at about this time several shifts in the focus of administrative personnel throughout the colony, away from the local administration of localities and toward large-scale infrastructural work on bridges and roads. One of the consequences of this was that many of the Belgian territorial personnel left the Lese-Dese area in 1932 (Hackars, report to Stanleyville, District du Kibali-Ituri, Historical Papers). In 1933, some correspondence took place between the administrative headquarters at Ituri and Stanleyville. The correspondence followed official reports that a military exercise of 1932, and exploratory reconnaissance with the Dese in the same year, revealed a situation that was less than satisfactory to the administration, which then had to decide whether or not it should unite the Dese and the Karo under one secteur or cheferrie . Unfortunately, the correspondence says nothing about why the Lese situation was so unsatisfactory, nor what specific actions Belgian military took against them.

The choice of Arambi as the new chief of the Lese-Dese came only

after a long and difficult decision in which KopaKopa, of the Andipaki phratry (now located at Malembi), opposed him (Baltus 1949). The administration described Arambi in a 1936 report:

The forest population of the Dese, who already give rise to fewer concerns than three or four years ago, will reach a level of political and economic evolution equal to that of their neighbors, if one can maintain in Mambasa the long-term presence of a good agent, endowed with as much tact as energy. Arambi, the chief candidate of the Dese, the only one to have garnered nearly all the votes of the Dese Notables , is a very calm fellow, very understated, more of a peacemaker and conciliator than one to organize new initiatives. Given the current conditions among the Dese, he is the best man politically. (P.V. 246, my translation)

Within a year, the Karo and Dese were, in fact, united, not under one chiefdomship but into a single administrative unit called the Frontière de Karo-Dese . This is the last official report of the colonial administration available to me: "Arambi was sworn in on March 31, 1937. The Karo-Dese border was drawn and recognized by decisions 245 of March 10, 1937, and 246 of March 9, 1937, by the Commissioner of the Kibali-Ituri district; relating respectively to the Karo and the Dese" District du Kibali-Ituri Historical Papers. (P.V. 246, my translation).[4] Arambi served for seven years until his death in 1943. Nekubai of the Andipai clan was named to be the new chief, and his new headquarters of the chiefdom was established at Ngbongupanda, approximately eighteen kilometers to the south of Malembi.

Relocation and Reorganization

During the early 1940s, the Lese who now occupy Malembi were expelled from their villages and forced to relocate around the proposed site of the north-south road; elders were excluded from resettlement, but since few of them wanted to stay alone in their villages, nearly all of them moved with their families. Although the Lese were told that they would have only a short period of obligatory labor, only later did they learn that the residence shift was to be permanent. The area the Belgians assigned to the Lese was one that had formerly been inhabited by the Masa phratry of the Lese-Karo and their associated Efe families, and though the Masa were not at that time occupying the sites that

[4] I wish to thank Scott Carpenter for assisting in the accurate translation of documents written in French.

became Lese-Dese villages, they nonetheless believed that the land remained theirs, especially the old abandoned gardens, which could be slashed and burned again and still produced small quantities of yams and tubers. Over the next few years, there were some bitter quarrels between the Lese-Dese and the Masa over access to the palm oil trees that grew near the Masa gardens. One particularly serious quarrel occurred between the Masa and the Andingire and Andingbana clans of the Lese-Dese Andisopi phratry:

The Europeans named Iapu to be capita of Andingire clan, and they gave him the area from Ngodingodi to Abdala's stream Anderu at Andingbana village. Koboni of the Andibuku clan received the area from the marsh to the Malembi River. Everything was Masa. Andingbana had no place. The Belgians tried to give Abasondo hill to Andingbana, but they did not want to go there. Iapu said they could remain next to Andingire, and gave them their current village. But we fought a lot over palm oil, and Andingbana and the Masa do not like each other. We had to give the Masa gifts of elephant, and other things.

Within a decade, the Lese-Dese and the Efe held firm control over their new land and trees. The Masa slowly moved north, began to intermarry with the Lese-Dese, and within a short time had shifted their chiefdom identity away from the Karo to the Dese, probably encouraged by the administration, which sought to keep the peace and simplify ethnic boundaries: if the Masa lived within the chiefdom of the Lese-Dese, they could not be designated as Lese-Karo. The Masa today refer to themselves as the Masa phratry of the Lese-Dese, but they remember that they were at one time Lese-Karo. Similarly, the Belgians relocated the Maru phratry of the Lese-Dese within the territory of the Lese-Karo chiefdom, and today the Maru claim to be Lese-Karo.

On the whole, despite the trouble with the Masa, the Lese-Dese were able to take up their new residences in some peace. Within the general area designated for the new Lese-Dese residences, most of the clans were able to choose their immediate neighbors, and could even reestablish the same kinds of spatial relations between clans and phratries that they had had before in what the Lese today refer to as their sapu , or ancestral villages. The main problem for the Lese was the smaller size of the new area. Before relocation, Lese villages were highly independent and for the most part self-sufficient social units, situated as far as fifteen kilometers from one another. This distance made it possible to group phratries well apart. Not all villages were exactly alike, but villages of the same phratry were closer together than villages or clans that

belonged to a different phratry. Lese elders remember the days before relocation as filled with feud and violence between villages and between phratries. They say that they sent Efe to other villages as spies to collect information on the availability of food and meat, and the numbers of women and children who lived there. If there was a great deal of food in another village, they might raid it; if there was an inequity in the number of women and children, they might capture or kill them to bring their levels into parity.

After relocation, although the Lese of Malembi were able to reestablish prior sequences of clans and phratries, it was not possible for them to locate their villages at great distance from one another. Instead of the widely spaced villages they had been accustomed to, now nearly twenty clans were resettled on the roadside within an administrative unit only twenty-seven kilometers long, so that few villages were more than two kilometers from another. This closer proximity of villages and settlement on a major road meant increased contact with non-Lese, and new competition for land and resources. Moreover, although these Lese had some choice in the matter of locating their villages, they were told by the Belgians, and then later by the state of Zaire, that they could shift their village sites only every seven years, instead of the customary two or three years. In addition, they were ordered to locate their villages at the roadside. From the point of view of the Lese, settlement at the roadside diminished the size of the forest because the area available for settlement and for clearing was limited by the close proximity of their neighbors.

Another major problem with relocation was the difficulty of maintaining the close Lese-Efe relations. Every Lese village maintained relations with Efe, and most of the Efe groups that were associated with the Lese villages were prepared to move along with their Lese to the roadside so that they could continue the relationships. This was by their own choice, not by any order of the Belgian administration. But many Efe clans did not move right away. Some remained with the few older Lese who did not resettle, others moved closer to Wamba to establish relations with the Budu farmers they had come to know through their Lese partners. Most of the latter never reestablished exchange relations with their Lese partners; some have changed their clan names, assumed specifically Budu names, and learned to speak the Budu language fluently. Efe informants describe relocation as an abrupt shift in their trading relations, a time of turmoil and uncertainty. Whether an Efe camp moved to the roadside or to Wamba, moving meant learning about new

stretches of forest and adapting to the demands of new historical conditions. To this day, many of the Efe and the Lese continue to return annually to their former area (sapu), sometimes for visits of one to three months.

Development in the Belgian Congo During the 1950S

Soon after World War II, the Belgians faced increasing criticism abroad and within the Congo over continued colonization. The Congo Reform Movement in England had long exerted pressure on the Belgian government to instigate reforms and to uphold the 1885 Berlin Conference's commitment to "free trade and welfare of the indigenous population" (Louis 1966; Morel 1906), and in response to this and other pressures, the Belgian administration had tried to expand education in the Congo in order to develop an African elite, possibly as a preparation for decolonization. By 1958, a state-run dispensary had been set up at Ngbongupanda (the administrative headquarters of the chiefdom of the Lese-Dese), and trained work elephants and machines had been sent to the Ituri to widen the north-south road to twelve meters and to build long drainage ditches.