Antonio Zantani

Zantani gained notoriety in Venetian music history by attempting to print four madrigals from the Musica nova in the late 1550s. But his links to Venetian music date from at least 1548 and involve the same Scotto edition in which Rore's Vergine cycle was printed. Besides the settings by Rore, this edition included works by Willaert, Perissone, Donato, and others that enhanced its Venetian character.[37] Most of Willaert's contributions were occasional, forming part of the dialogic networks I have attempted to describe here. Among them was a dedicatory setting of Lelio Capilupi's ballata Ne l'amar e fredd'onde si bagna[38] a tribute to a renowned Venetian noblewoman whom Capilupi named with the epithet "la bella Barozza" — Antonio's wife.[39] Its praise of her sets the Petrarchan paradox of the icy fire in a verbal landscape shaped by Venetian geography: her flame, born in the cold Venetian seas, burns so sweetly that the fire from which the poet melts seems frigid beside it.

Ne l'amar e fredd'onde si bagna In the bitterness and cold in which

L'alta Vinegia, nacque il dolce foco The great Venice bathes itself was born the sweet fire

Ch'Italia alluma et arde a poco a poco. That inflames and illumines Italy bit by bit.

Ceda nata nel mar Venere, e Amore Venus, born of the sea, may yield, and Cupid

Spegna le faci homai, spezzi li strali May put out the torches and break his arrows;

Chè la bella Barozz'a li mortali For the lovely Barozza stabs the mortals

Trafigge et arde coi begl'occhi 'l core. And consumes their hearts with her beautiful eyes.

E di sua fiamma è sì dolce l'ardore, And there is such a sweet ardor from her flame

Che quell'ond'io per lei mi struggo e coco That that which makes me melt and burn for her

Parmi ch'al gran desir sia freddo e poco. Seems frigid and small beside the great desire.

Barozza's full name was Helena Barozza Zantani. In 1548 she already had a reputation as one of Venice's great beauties. She had been painted by Titian and Vasari, venerated by Lorenzino de' Medici, and widely celebrated in verse.[40] These tributes

[37] A number of these pieces reappear in the manuscript of the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, Guelf 293. See Lewis, "Rore's Setting of Petrarch's Vergine bella," pp. 407-8, for a list of its contents and concordances.

[38] The setting is among those in Wolfenbüttel 293. The poem appears in Rime del S. Lelio, e fratelli de Capilupi (Mantua, 1585), p. 31. For my identification of the poet I am indebted to Lorenzo Bianconi and Antonio Vassalli's handwritten catalogue of poetic incipits, which gave me the initial lead on this and a number of other poems.

[39] Many sources confirm that Helena was Antonio's wife, including Dragoncino's designation of his stanza "Consorte di M. Antonio" (see n. 42 below); Aretino's paired letters to "Antonio Zentani" and "Elena Barozza" from April and May 1548, respectively (Lettere di M. Pietro Aretino, 6 vols. [Paris, 1609], 4:207' and 208'; Lettere sull'arte di Pietro Aretino, commentary by Fidenzio Pertile, ed. Ettore Camesasca, 3 vols. in 4 [Milan, 1957-60] 2:215-17); and the wills of Antonio and Helena, as given in Appendix, C and D.

[40] Both portraits are described by Pietro Aretino and both are now apparently lost. Vasari's was painted before he left Venice in 1542 (cf. n. 86 below); see Aretino, Lettere, 2:304' (no. 420, to Vasari, 29 July 1542, with a sonnet in praise of Barozza) and 4:208' (no. 478, to Helena, May 1548, with reference to both portraits), and Lettere sull'arte 1:224 and 2:216-17.

On Lorenzino's unrequited feelings for Helena Barozza, and for the most thorough gathering of information on her, see L[uigi] A[lberto] Ferrai, Lorenzino de' Medici e la società cortigiana del cinquecento (Milan, 1891), pp. 343-52, esp. p. 347 n. 2.

placed Helena in the cult of beautiful gentildonne, which assigned Petrarch's metaphorical praises to living ladies and generated yet more goods for Venetian printers.[41] Of all these praises, those in lyric forms were most apt to adopt something close to the lightly erotic tone of Capilupi: Giovambattista Dragoncino da Fano's Lode delle nobildonne vinitiane del secolo moderno of 1547, for instance, devoted one of its stanzas to the "sweet war" Helena launched in lovers' hearts, ending in praise of her "blonde tresses."[42]

Other encomia conflated her beauty with her moral worth. Confirming the occult resemblance thought to exist between physical and spiritual virtue, they deflected the transgressive possibilities to allure and mislead the unsuspecting to which beauty was also commonly linked. A letter of Aretino's to Giorgio Vasari of 1542 honored Vasari's portrait of Helena for the "grace of the eyes, majesty of the countenance, and highness of the brow," which made its subject seem "more celestial than worldly," such that "no one could gaze at such an image with a lascivious desire."[43] Aretino troped his own letter in an accompanying sonnet, declaring her loveliness of such an honesty and purity as to turn chaste the most desirous thoughts (see n. 43 below). Lodovico Domenichi's La nobiltà delle donne similarly joined beauty with virtue by comparing Helena's looks with the Greek Helen of Troy and her honesty with the Roman Lucrezia ("Mad. Helena Barozzi Zantani, laquale in bellezza pareggia la Greca, & nell'honestà la Romana Lucretia . . .").[44] Even the female poet-singer Gaspara Stampa added to her Rime varie a sonnet for Barozza, that "woman lovely, honest, and wise" (donna bella, onesta, e saggia).[45]

Like most of the women exalted by this cult, the virtuous Helena was safely sheltered by marriage. This ideally suited her to the Petrarchan role of the remote and unattainable lady, as it was now employed for numerous idolatries of living women.

[41] For documentation of the literary activity generated by these cults see Bianchini, Girolamo Parabosco, pp. 278-98, and on Helena, pp. 294-96.

[42] Fol. [4].

[43] Verses 9-11: "Intanto il guardo suo santo e beato/ In noi, che umilemente il contempliamo,/Casto rende il pensiero innamorato (Lettere 2:304' and Lettere sull'arte 1:224).

[44] Fol. 261 in the revised version printed by Giolito in 1551. Domenichi was an interlocutor in Doni's Dialogo della musica and a Piacentine comrade of Parabosco's. The theme of Troy echoed again at the end of Parabosco's I diporti, as a group of Venice's most prominent literati enthuse over various Venetian women in the popular mode of galant facezie, in between recitations of novelle and madrigali. The Viterban poet Fortunio Spira exclaims, "Che dirò di te . . . madonna Elena Barozzi così bella, così gentile! oh! se al tempo della Grecia tu fossi stata in essere, in questa parte il troiano pastore senza dubbio sarebbe stato inviato dalla Dea Venere, come in luogo dove ella meglio gli havesse potuto la messa attenere!" See Giuseppe Gigli and Fausto Nicolini, eds., Novellieri minori del cinquecento: G. Parabosco — S. Erizzo (Bari, 1912), p. 192. (I diporti were first published in Venice ca. 1550; see Chap. 4 n. 30 below.) Also directed to Helena may be a letter and three sonnets in Parabosco's Primo libro delle lettere famigliari (Venice, 1551) addressed "Alla bellissima, et gentilissima Madonna Helena" and dated 30 April 1550 (fols. 49-50). Parabosco makes intriguing mention there of "il nostro M.A. ilquale compone libri delle bellezze, & delle gratie vostre: con certezza che gli possa mancar piu tosto tempo, che suggetto. io vi faccio riverenza per parte sua, & mia" (our Messer A., who composes books of your beauties and graces, with the certainty that he may be lacking time, rather than a subject. I revere you for his part and mine); fol. 49.

[45] Rime (Venice, 1554), no. 278; mod. ed. Maria Bellonci and Rodolfo Ceriello, 2d ed. (Milan, 1976), p. 264. On the tributes of Stampa and others to Helena Barozza see Abdelkader Salza, "Madonna Gasparina Stampa, secondo nuove indagini," Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 62 (1913): 31.

But it also suggests that the music, writings, and paintings in her honor participated in loose networks of reference and praise that helped situate familial identities within larger civic structures. Indeed, it raises the possibility that some were spousal commissions meant (like Willaert's madrigal) to embellish the domestic household and redound to the family name: Helena's husband, Antonio, could after all count himself among the most avid of aristocratic devotees to secular music at midcentury and a keen patron of the visual arts.

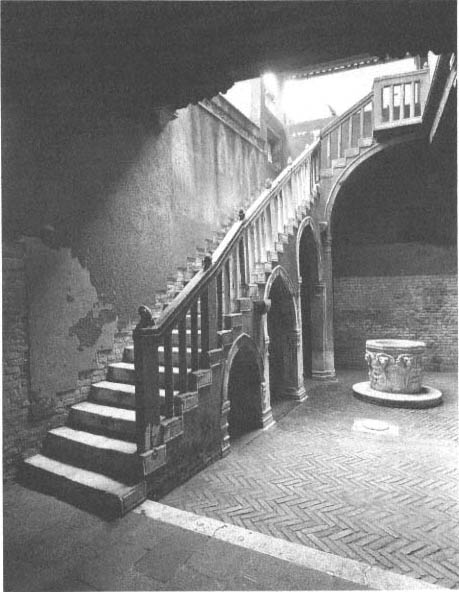

Zantani's vita will set the stage for reexamining relationships between civic identity and patronage at closer range.[46] Antonio was born on 18 September 1509 to Marco Zantani and Tommasina di Fabio Tommasini.[47] His father descended from a line of Venetian nobles, his mother from a family originally from Lucca and admitted to the official ranks of Venetian cittadini only in the fourteenth century.[48] In 1532 Antonio gained an early admission to the Great Council,[49] and on 16 April 1537 he and Helena were wed in the church of San Moisè.[50] Their respective wills of 1559 and 1580 identify their residence as being in the congenial neighborhood parish of Santa Margarita (see Appendix, C and D).[51] Inasmuch as Antonio's family clan was very small, they may also have lived at times, or at least gathered, at the beautiful Zantani palace nearby at San Tomà (Plate 12) — quarters that would have suited well the salon over which Zantani presided at midcentury.[52] Most famous of the earlier Zantani was Antonio's

[46] For a biography of Zantani see Emmanuele A. Cicogna, Delle inscrizioni veneziane, 6 vols. (Venice, 1827), 2:14-17. A briefer and more readily available biography, mainly derived from Cicogna, appears in Lettere sull'arte 3/2:528-30. Where not otherwise noted my biographical information comes from Cicogna.

The main contemporaneous biography is that given in the form of a dedication to Zantani by Orazio Toscanella in I nomi antichi e moderni delle provincie, regioni, città . . . (Venice, 1567), fols. [2] — [3']. It is reproduced in Appendix, E.

[47] I-Vas, Avogaria di Comun, Nascite, Libro d'oro, Nas. I.285. Marco and Tommasina were married in 1503 (I-Vas, Avogaria di Comun, Matrimoni con notizie dei figli).

[48] This information comes from Giuseppe Tassini's manuscript genealogy "Cittadini veneziani," I-Vmc, 33.D.76, 5:37-38, which, however, puts her marriage to Marco in 1505 (cf. n. 47 above). Tommasina drew up her will on 9 August 1566 (I-Vas, Archivio Notarile, Testamenti, notaio Marcantonio Cavanis, b. 196, no. 976), calling herself a resident of the parish of Santa Margherita.

[49] See Cicogna, Inscrizioni veneziane 2:14. (The date of 1552 given in Lettere sull'arte 3/2:528 is wrong.) On the practice of admitting young noblemen to the Great Council before their twenty-fifth birthdays see Stanley Chojnacki, "Kinship Ties and Young Patricians in Fifteenth-Century Venice," RQ 38 (1985): 240-70.

[50] I-Vas, Avogaria di Comun, Matrimoni con notizie dei figli. A marriage contract survives in the Avogaria di Comun, Matrimoni, Contratti L.4, fol. 381' (reg. 143/4), but is not currently accessible to the public.

[51] Helena's will was kindly shared with me by Rebecca E. Edwards. Cicogna refers to a will of 10 October 1567 that Zantani made just before his death, which is preserved in the Testamenti Gradenigo (Inscrizioni veneziane 2:16n.). Presumably it is included in the extensive Gradenigo family papers at I-Vas, which are as yet insufficiently indexed. (I am grateful to Anne MacNeil for inquiring about this.) Michelangelo Muraro cites an ostensible copy of the will at I-Vmc, MS P.D. 2192 V, int. 12, but the document in question is presently missing; Il "libro secondo" di Francesco e Jacopo dal Ponte (Bassano and Florence, 1992), p. 382. Cicogna quotes enough of this will, however, to show that Zantani took pains to have his name day celebrated every year thereafter: "Egli fu l'ultimo della casa patrizi Zantani, e col suo testamento ordinò che delle sue entrate fosser ogn'anno de' trentasei nobili dassero in elezione nel Maggior Consiglio."

[52] Zantani's clan died out with his death. Nonetheless, Pompeo Molmenti's statement that Antonio lived in the present Casa Goldoni is oversimple; see La storia di Venezia nella vita privata dalle origini alla caduta della repubblica, 7th ed., 3 vols. (Bergamo, 1928), 3:360-61. For the information, noted by Dennis Romano, that Venetian patrician families often had residences in several different parishes see Chap. 1 above, n. 1.

12.

Main staircase, Casa Goldoni, formerly Palazzo Centani (Zantani), parish of San Tomà.

Photo courtesy of Osvaldo Böhm.

grandfather of the same name, who had reputedly battled the Turks and been brutally killed and dismembered for public display while a governor in Modone.[53] According to one account, it was owing to "the glorious death of his grandfather" that Antonio gained his title of Conte e Cavaliere, bestowed with the accompaniment of an immense privilege by Pope Julius III, who occupied the papacy between 1550 and 1555.[54] Later in life Antonio served as governor of the Ospedale degli Incurabili. One of his memorable acts, as Deputy of Building, was to order in 1566 the erection of a new church modeled on designs of Sansovino.[55] He died before he could see it, in mid-October 1567, and was buried at the church of Corpus Domini.[56]

Music historians remember only two major aspects of Zantani's biography. The first is that he was foiled in trying to publish a collection of four-voice madrigals that included four Petrarch settings from the Musica nova, then owned exclusively by the prince of Ferrara. The second is that he patronized musical gatherings at his home — gatherings that involved Perissone, Parabosco, and others in Willaert's circle, as recounted in Orazio Toscanella's dedication to him of his little handbook on world geography, I nomi antichi, e moderni (given in full in Appendix, E).

It is well noted that you delight in music, since for so long you paid the company of the Fabretti and the company of the Fruttaruoli, most excellent singers and players, who made the most fine music in your house, and you kept in your pay likewise the incomparable lutenist Giulio dal Pistrino. In the same place convened Girolamo Parabosco, Annibale [Padovano], organist of San Marco, Claudio [Merulo] da Correggio, [also] organist of San Marco, Baldassare Donato, Perissone [Cambio], Francesco Londarit, called "the Greek," and other musicians of immortal fame. One knows very well that you had precious musical works composed and had madrigals printed entitled Corona di diversi.[57]

Among the recipients of Zantani's patronage, then, were guilds of instrumentalists and singers, solo lutenists, organists, chapel and chamber singers, and polyphonic composers (primarily of madrigals and canzoni villanesche ), several of them doubling in various of these roles. Both the Fabretti and the Fruttaruoli were long-established groups. The Fabretti were the official instrumentalists of the doge, performing for many of the outdoor civic festivals, and the Fruttaruoli a confraternity

[53] For modern biographies of Antonio's grandfather and father, see Cicogna, Inscrizioni veneziane 2:13-14.

[54] See Toscanella's dedication to Zantani, I nomi antichi, e moderni, fol. [3], with further on Zantani's family, heraldry, etc. The origins of Zantani's knighthood with Julius III would seem to be confirmed by a manuscript book on arms written by Zantani and titled "Antonio Zantani conte e cavaliere del papa Iulio Terzo da Monte," as reported by Cicogna, Inscrizioni veneziane 2:16. If Toscanella was right about the immense size of the privilege, this may account for Zantani's apparent increase in patronage in the early to mid-1550s.

[55] See Bernard Aikema and Dulcia Meijers, Nel regno dei poveri: arte e storia dei grandi ospedali veneziani in età moderna, 1474-1797 (Venice, 1989), p. 132, and Muraro, Il "libro secondo," p. 382.

[56] The church was secularized in 1810 and later destroyed; see Giuseppe Tassini, Curiosità veneziane, ovvero origini della denominazioni stradali di Venezia, 4th ed. (Venice, 1887), pp. 208-10. On Zantani's death date see Cicogna, Inscrizioni veneziane 2:16.

[57] See Appendix, E, fol. [2']. The passage was first quoted and trans. in Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:446-47.

that likewise performed outdoor processions.[58] Apparently Zantani paid members of both the Fabretti and Fruttaruoli over a considerable time and, as Toscanella's wording implies, also kept the lutenist dal Pistrino on regular wages, perhaps as part of his domestic staff. Toscanella did not mean to suggest that these musicians all convened ("concorrevano") at once, but he was calling up the idea of collective gatherings in the sense of private musical academies.[59]

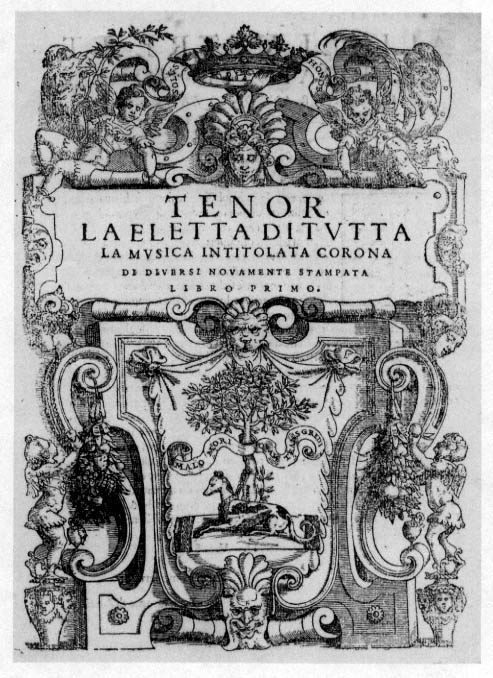

Zantani's foiled efforts in music printing might be seen as part of a larger attempt to increase his familial patrimony. In approximately 1556-57 he assembled with the aid of another gentleman, Zuan Iacomo Zorzi, the musical anthology that eventually led to his confrontation with agents protecting the interests of the prince of Ferrara. The anthology was to be published with an ornate title page and with the title La eletta di tutta la musica intitolata corona di diversi novamente stampata: libro primo (Plate 13).[60] Zorzi contributed a dedication addressed to none other than Zantani himself (Plate 14) — this despite the fact that Zantani was not only the print's backer but in reality its chief owner and producer. Zorzi's dedication praised

[58] The latter were named for their renowned promenade on the so-called Feast of the Melons, which reenacted an occasion when they had been feted with melons by Doge Steno — an honor that they repeated ritually in every first year of a doge's reign by bearing melons in great flowered chests and small silver basins on a certain day in August and processing with trumpets, drums, and mace bearers from the campo of Santa Maria Formosa through the Merceria and piazza San Marco to the Ducal Palace. For further information see Giuseppe Tassini, Curiosità veneziane, ovvero origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia, rev. ed. Lino Moretti (Venice, 1988), pp. 266-67: "[L]a confraternita dei Fruttajuoli, eretta fino dal 1423, aveva qui un ospizio composto di 19 camere, ed un oratorio sacro a S. Giosafatte. Quest'arte, unita a quella degli Erbajuoli, aveva un altro oratorio dedicato alla medesimo santo presso la chiesa di S. Maria Formosa. I Fruttajuoli col Erbajuoli erano gli eroi della cosi detta festa dei Meloni. Dovendo essi presentare al doge nel mese d'agosto del primo anno del di lui principato un regalo di meloni (poponi), solevano nel giorno determinato raccorsi in Campo di S. Maria Formosa, e per la Merceria, e per la Piazza di S. Marco, preceduti dallo stendardo di S. Nicolò e da trombe, tamburri e mazzieri [mace-bearers], recarsi in corpo a palazzo, portando i poponi in grande ceste infiorate, e sopra argentei bacini. Introdotti nella Sala del Banchetto, complivano il doge per mezo del loro avvocato, poscia gli facevano offrire da due putti un sonetto ed un mazzolino di fiori, e finalmente fra mezzo le grida di Viva il Serenissimo! consegnavano i poponi allo scalco ducale."

[59] We can deduce what stretch of time Toscanella's description covered by considering the musicians' biographies. Of the madrigalists mentioned, Parabosco came to Venice around 1540, Perissone at least by 1544, and Donato by 1545, whereas the minor composer and contralto Londariti was hired into the chapel at San Marco only in 1549 (see Chap. 9 below, n. 4 and passim). By 1557 Parabosco had died. Londariti left the chapel around the same time (see Ongaro, "The Chapel of St. Mark's," pp. 187-88, who dates his departure between 6 April 1556 and 10 December 1558), and Perissone had most likely passed away by 1562 (ibid., p. 165 n. 194 and Document 272).

Giulio dal Pistrino is almost undoubtedly the same as Giulio Abondante, who published five books of lute music (three extant) between 1546 and 1587. See Henry Sybrandy, "Abondante, Giulio," in The New Grove 1:20, and Luigi F. Tagliavini, "Abondante, Giulio," Dizionario biografico degli italiani 1:55-56.

The organists Padovano and Merulo did not enter San Marco until 1552 and 1557, respectively, Merulo having taken Parabosco's place on the latter's death; but Padovano, true to his name, was a Paduan who had long been in the area, and Merulo has been placed in Venice at least as early as 1555. The latest information on these organists has been amassed by Rebecca A. Edwards, "Claudio Merulo: Servant of the State and Musical Entrepreneur in Later Sixteenth-Century Venice" (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1990), to whom I am grateful for sharing various information before her dissertation was filed. On Padovano and his family, see Edwards, p. 94 n. 27. Edwards speculates that since Merulo witnessed a document for Zantani in Venice on 27 November 1555 (p. 214 n. 2) he may have been studying in Venice for some time before 1555, possibly under Parabosco (pp. 269-70). Merulo's close ties with Parabosco can be deduced from the dedication of the latter's Quattro libri delle lettere amorose (Venice, 1607) by the editor Thomaso Porcacchi, who called Merulo "ora molto intrinseco del Parabosco che glie l'haveva lasciate [i.e., le lettere ] in mano avanti la sua morte"; see Edwards, p. I n. I. Edwards also establishes that the printer and bookseller Bolognino Zaltieri, whom Toscanella names as having engaged him to assemble I nomi antichi, e moderni ("diede carico à me in particolare di raccorre . . . i Nomi antichi, & moderni," fol. [2]), was one of Merulo's partners; see Chap. 3 and Chap. 4, pp. 217-18.

[60] The "corona" was probably a reference to the Zantani family heraldry. See Appendix, E, fol. [3].

13.

La eletta di tutta la musica intitolata corona di diversi novamente stampata:

libro primo (Venice, 1569), title page.

Photo courtesy of Musikabteilung der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

14.

La eletta di tutta la musica intitolata corona di diversi novamente

stampata: libro primo (Venice, 1569), dedication from Zuan Iacomo

Zorzi to Antonio Zantani. Photo courtesy of Musikabteilung der

Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

Zantani as the "'padre' of musicians, literati, sculptors, architects, painters, antiquarians . . . [and] all sorts of honored men."

The anthology (or most of it) was apparently printed by about 1558 but not issued until 1569, ten years after the Ferrarese had brought out the Musica nova. It is worth recounting a bit of the well-known story behind the print and its relation to

Willaert's Musica nova,[61] because it tells us a lot about Zantani's character and about the new function Petrarchan tropes and styles assumed in helping to define identity in a thickly populated urban world. Zorzi had secured the original privilege for La eletta in 1556, but Zantani immediately had it transferred to his own name. Apparently he wanted to avoid the vulgar process of procuring the privilege himself, which it was the usual business of printers to do.[62] On 19 January 1557 Zorzi was granted the privilege for the print along with approval to essay a new printing technique. And both were transferred to Zantani on 29 March 1557.[63]

The anthology was obviously hot property from the start. In addition to Willaert's previously unpublished Petrarch settings, it included new works by Willaert's prominent disciples Donato and Perissone.[64] Unlike the Musica nova, La eletta was planned from the outset as an appealing four-voice potpourri. The reader for La eletta's Venetian license summarized its literary contents as "diverse types of poems" such as "canzoni, sonetti, madrigali, sestine, ballate, and so forth . . . treating youthful topics and amorous emotions."[65]

Ironically, this project brought the Cavaliere more lasting notoriety than any of his other ventures. When Zantani planned the publication he undoubtedly intended the settings from the Musica nova to crown it. He probably got hold of them through his connection with Willaert's three protégés, Parabosco, Perissone, and Donato: it was they who, between 1545 and 1553, had published parallel settings imitating those that later became part of Willaert's Musica nova collection and who therefore must have had closest access to them.[66] As it turned out, however, Polissena Pecorina had already sold the whole corpus (or something close to the printed version of it) with sole rights to Prince Alfonso d'Este, who meant to have it published by Gardane in an exclusive complete edition. The news that Zantani's

[61] For a retelling of the story with illuminating new details and copious documentation see Richard J. Agee and Jessie Ann Owens, "La stampa della Musica nova di Willaert," Rivista italiana di musicologia 24 (1989): 219-305. The authors were kind enough to share the article with me in typescript before its publication. Since Agee and Owens publish all of the relevant documents thus far known, I cite their article for documents, including ones first unearthed by others.

[62] Agee and Owens, "La stampa della Musica nova," Document 7, pp. 246-47. The documents directly concerning printing privileges were nearly all first transcribed in Richard J. Agee, "The Privilege and Venetian Music Printing in the Sixteenth Century" (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1982).

[63] Ibid., Documents 9 and 10, pp. 248-49 (originally located by Martin Morell), which mention the use of new characters and staves.

[64] The settings by Rore, Ferrabosco, Francesco dalla Viola, Heinrich Schaffen, and Ivo had all been published before 1556. The three settings by Donato were not brought out elsewhere until Donato's Secondo libro a 4 was issued in 1568. Three of Perissone's four were still unique in 1569 (a fourth had come out in Gardane's print De diversi autori il quarto libro de madrigali a quattro voci a note bianche novamente dato in luce (Venice, 1554); Vogel/Einstein 15541; RISM 155428). This left only the following settings (in addition to Perissone's) as apparently unique to La eletta when it was finally issued: single madrigals by Giachet Berchem and Sperindio and a group of eight settings by Giovan Contino, all clustered toward the end of the volume. In all, its cultural capital had radically dropped.

[65] See the reader's report for the license cited in Agee and Owens, "La stampa della Musica nova, " Document 4, dated 28 November 1556: "ho letto, et ben esaminato alcune rime diverse, poste in canto, et altre volte stampate, come sono Canzoni, Sonetti, Madrigali, Sestine, Ballate, etcetera né in quelle ho ritrovato cosa contra nostra Santa fede né contra l'honore et fama di alcun principe, Et con tutto che trattino materie giovanili, et affetti amorosi, non sono però tali, che non si possino stampare senza pericolo che corrompino gli buoni costumi" (p. 245).

[66] See Chap. 9 below.

print was to be issued imminently with Willaert's four-voice madrigals came to the prince's attention only in late 1558, setting off a volley of hostile exchanges between a whole cast of characters, Venetian and Ferrarese: Zantani; the unhappy Ferrarese ambassador in Venice, Girolamo Faleti; Alfonso's secretary at home, Giovanni Battista Pigna; and Alfonso's father, Duke Ercole.[67]

Clearly Zantani had pinned great expectations on his intended Corona, in which he had already invested considerable labor and funds by Christmas 1558, when notice of it reached the sponsors of Musica nova in Ferrara.[68] In the battle that ensued, Zantani turned hot with anger and humiliation. A famous letter to Faleti from late 1558 sputtered indignantly at the idea that those two "mecanici" Gardane and Zarlino should be allowed to hamper the well-laid plans of a nobleman like himself.

I would never have thought that you would ever create such displeasure about something by which I am made unhappy or that you would give such trouble as you have to the petition of certain tradesmen like Gardane and Father Gioseffe Zarlino and, without giving me to understand anything, order me now to dispense with the four madrigals taken out of the book of Mr. Adrian . . . (and not even taken out in such numbers as they are [found] in that book); and they have removed your authority ["mezo"] and that of your excellent Duke. To you I am just a servant of yours and moreover to Francesco dalla Viola and those other mercenary people. But you know very well that my father was a consigliere and always very favored in his dealings even by the doge and now I on the contrary must accept this offense. I can never believe that the Duke should want to create such vexation not only for me but all my relatives. I tell you now that my privilege is also [at issue] here and in my petition it says that I was making "a selection from all the madrigals both printed and not printed" and this was in 1556. But I turn to you and say that I will be grieved by you interminably that for four madrigals you should use me thus.[69]

[67] Pecorina's role and many details of these exchanges were first brought to light by Anthony Newcomb, "Editions of Willaert's Musica Nova: New Evidence, New Speculations," JAMS 26 (1973): 132-45. Other studies have followed up on this and various other aspects of the Musica nova 's printing history, namely David S. Butchart, "'La Pecorina' at Mantua, Musica Nova at Florence," Early Music 13 (1985): 358-66, and most recently Agee and Owens, "La Stampa della Musica Nova. "

[68] Agee and Owens, "La stampa della Musica nova, " Document 48, pp. 276-77 (see also n. 71 below).

[69] Ibid., Document 45, p. 274: "Io non harei mai pensato che V.S. mi fese mai dispiacer né cosa che per lei mi dolese e dese fastidio che a peticion de certi mecanici come è il Gardana, Pre Isepo Zerlin, senza averme mai fato intender cosa alcuna, farmi far hora comandamento ch'io dispena quatro madrigali tolti fuora del libro di m. Adriano et non più in tanto numero che sono in quel libro et hano tolto il vostro mezo e della eccellentia del signior duca. Io li son ancora mi suo servitor et piu di Francesco Dalla Viola et st'altri mercenarii et sa ben V.S. che sempre che mio padre esta consegier ancio[?] dose si è stato sempre favorevole in le cose sue et che hora mo alincontro per ben io deeba [sic] ricever mal io non posso mai creder che'l signior duca mi voglia usarmi dispiacer non solum a me, ma eciam a tutto il mio parentado. Io ve dicho che'l mio privilegio si è ancian a questo et in la mia suplica dice ch'io ho fato una selta de tutti i madrigali cusì in stampa come non in stampa et questo fo del 1556 ma vi torno adir che [ ] mi dolarò di voi in sempiterno che per quatro madrigali usarme tal termine." The letter is undated, but Agee and Owens note that it was written no later than 6 December 1558. Facs. in Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart, vol. 14, cols. 671-72. My translation does not attempt to eliminate the awkwardness of the original.

On the positions held by Antonio's father, who became a consigliere to doge Lorenzo Priuli in 1557, see G. B. di Crollalanza, Dizionario storico-blasonico delle famiglie nobili e notabili italiane estinte e fiorenti, 3 vols. (Pisa, 1886-90; repr. Bologna, 1965) 3:119.

To Zantani's mind the Ferrarese were launching a direct assault on his kin and his venerable social status. In the wake of the feud Zantani was even contemplating a lawsuit. Owing to the machinations of Pigna he did not follow through on this. Pigna enlisted the efforts of the weary Faleti to urge Zantani away from jeopardizing Prince Alfonso's good graces simply in order to thwart a lowly composer like Francesco dalla Viola, who was only engineering the publication on the prince's behalf.[70] On Christmas Day 1558, after securing Zantani's reluctant cooperation, Faleti wrote a beleaguered report to Duke Ercole, updating him on the current state of affairs. Here we see Zantani's ire in a profoundly Venetian light.[71] The Ferrarese should not imagine that it is in Faleti's power to make the Cavaliere stop sounding his case and stop trying to retain his privilege in order not to lose a "great deal of money that he has spent in printing his work." For "it is the custom of this Republic to let everyone be heard, not to say one of their most principal nobles, for whom so many have by now exerted themselves."[72]

Nonetheless, after all rank had been pulled, it was Ercole and Alfonso who came off victors — courtly princes over city nobles. Zantani apparently agreed reluctantly to delay publication of La eletta for a ten-year period. When it was finally issued, with Zorzi's dedication to Zantani, the Cavaliere had been dead for two years.

These musical activities formed part of a dense thicket of patronage activities discernible through both dialogic writings and art-historical chronicles. All told, they reveal Zantani as an avid collectionist, who added music as part of the vernacular arts to other artifacts favored by Venetian antiquarian types, especially medals, antiques, and portraits. All of these were common fare among local patricians, who heaped honor on their families' names by their systematic additions to domestic patrimony. Antonio stands apart from most other patrons in actually performing the labors of some of the artisanal crafts he patronized. In addition to the music-printing technique he invented, he produced his own prints of engraved coins.[73] He practiced the art of engraving himself, as well as painting and, even more surprisingly, the gentler work of embroidery.[74]

Zantani's dual roles as amateur artisan and collector were brought together most intensely in his work with medals. In time he assembled one of the most noted medal collections of his day and by 1548 collaborated with the famous engraver

[70] Agee and Owens, "La stampa della Musica nova, " Document 47, pp. 275-76.

[71] Ibid., Document 48, pp. 276-77.

[72] "[S]e questi pensano che sia di mio potere il fare che predetto Cavaliere non produca le sue ragioni a diffesa sua et a mantenimento del suo privileggio per non perdere una grossa spesa che ha fatto nel stampar l'opera sua, s'ingannano, essendo costume di questa Republica il dar modo a tutti che siano uditi nelle loro ragioni, ne che a uno de principalissimi suoi gentil'huomeni a favore del quale homai tanti si sono messi" (ibid.).

[73] On the former see ibid., Documents 9 and 10, pp. 248-49.

[74] See Toscanella, I nomi antichi, e moderni, fol. [2']: "Non è nascoso ancora, che S. S. C. dipinge, ricama & intaglia sopra ogni credenza bene."

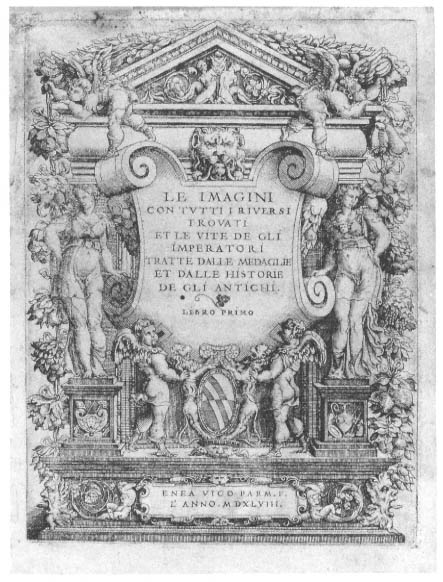

Enea Vico in producing Le imagini con tutti i riversi trovati et le vite de gli imperatori tratte dalle medaglie et dalle historie de gli antichi. Libro primo, a book of medals depicting the first twelve Roman emperors together with a large variety of reverses portraying their lives.[75]

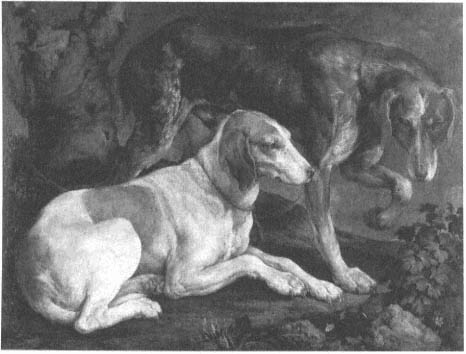

Zantani may well have printed Le imagini himself, or at least been centrally involved in doing so. Embedded in the elegant title page was the Zantani coat of arms and at the base of the left-hand column Zantani's crest showing a leopard and a scimitar in memory of his grandfather's bravery (Plate 15). On the final recto is Zantani's printer's mark, a device of a leashed dog (Plate 16), decorated with two mottoes that locate the crafts of printing and engraving within standard themes of civic virtue: "Solus honor" and "Malo mori quam transgredi" ("Only honor" and "I would rather die than transgress"). The dog, as it turns out, occupied a special place in Zantani's symbolic system. The only painting Zantani is undisputably known to have commissioned was one done by Jacopo dal Ponte around 1550 of Zantani's two hounds (Plate 17).[76] Moreover, elements of canine iconography found in Le imagini reappeared on the title page of La eletta (Plate 13), where a leashed dog was positioned at the base of the cartouche with Zantani's mottoes draped around the dog's tree and on the crown at the top. Within this symbolic network the dog represented honor and fidelity. As the first substantial artifact that Zantani bequeathed to posterity, Le imagini thus designates an ethical and intellectual space with intriguing symbolic links to the views of patrimonial objects he later expressed concerning La eletta. While speaking outwardly to collecting, Le imagini's prefaces and plates moralize ancient history as the vaunted prototype for sixteenth-century forms of patriarchy.

Zantani clearly did not do any of the actual engraving for the volume; rather, he allotted to himself the tasks of writing two prefaces and collecting and organizing the medals' reverses, with representations of the emperors' careers.[77] At the outset of the prefaces Zantani insists that his main labor, that of comprehending the totality of the emperors' lives and deeds in visual portrayals, has been a historical one. The reader's task, he claims, should (like his) be to consider the ancients' actions with the intellect

[75] Aretino's praise of this work in a letter dated April 1548 suggests it had been already printed by that month (Lettere 4:207'; repr. in Letter sull'arte 2:215-16). The projected second book was never published, and in some copies (like that at Harvard) the words "Libro primo" have been scraped away. On Le imagini see also Marino Zorzi, ed., Collezioni di antichità a Venezia nei secoli della repubblica (dai libri e documenti della Biblioteca Marciana) (Rome, 1988), pp. 70-71.

[76] I am grateful to David Rosand for this information (private communication) and for sending me proofs from Muraro, Il "libro secondo," which documents that the commission was made in 1548 and paid for in 1550 (pp. 70-71). The painting was acquired by the Louvre while this book was in press.

[77] This is the division of labor suggested by Vico in his Discorsi . . . sopra le medaglie de gli antichi divisi in due libri (Venice, 1558), where he refers to the "medaglie di rame di Augusto, nel libro de' riversi de' primi XII. Cesari da me fatto e gia in luce (di cui è stato autore l'honorato cavalliere m. Anton Zantani)" (p. 84). It is not absolutely certain who published the book, but Zantani is the most likely candidate since his family arms appear on the title page; see Crollalanza, Dizionario storico-blasonico 3:119/2, and Eugenio Morando di Custoza, Libro d'arme di Venezia (Verona, 1979), tavola CCCLXXX, no. 3413. The Latin translation of the work issued in 1553 as Omnium caesarum verissime imagines ex antiquis numismatis desumptae replaced Zantani's arms with the lion of Venice and made various other alterations; the entry in the National Union Catalogue attributes the printing of this later volume to Paolo Manuzio, as does Ruth Mortimer, Harvard College Library, Department of Printing and Graphic Arts: Catalogue of Books and Manuscripts, pt. 2, Italian Sixteenth-Century Books, vol. 2 (Cambridge, Mass., 1974), p. 778.

15.

Le imagini con tutti i riversi trovati et le vite de gli imperatori tratte dalle

medaglie et dalle historie de gli antichi: libro primo (Venice, 1548), title page.

Photo courtesy of the University of Chicago, Special Collections.

16.

Le imagini con tutti i riversi trovati et le vite de gli imperatori tratte dalle

medaglie et dalle historie de gli antichi: libro primo (Venice, 1548), printer's mark.

Photo courtesy of the University of Chicago, Special Collections.

as much as to gaze at their portraits with the eyes.[78] This admonishment precipitates an awkward moral lesson. From looking and reading "one sees and appreciates the value of virtue, to what unhappiness wrongdoing leads, of what profit is honest conversation, how easily men's thoughts change, how a virtuous man is really free and an evil one a servant, and finally how no one can escape the providence of God in receiving either penalties or rewards."[79] As the embodiment of the virtues Zantani aimed to depict, the emperors' lives were necessarily idealized to mirror the mythologized self-imagery that made Venice out as a new Rome.[80] This preoccupation with moral ques-

[78] "[I]o intendo di dare in luce le imagini de gli imperatori tratte dalle antiche medaglie con tutte quelle maniere di riversi che alle mani pervenute mi sono, come che non picciol fatica in ciò habbi havuta, & aggiugnervi la somma delle vite, & operationi fatte da quegli. . . . Prendete adunque ò lettori questa dimostratione di buona volontate verso voi, & quanto con l'occhio del corpo riguarderete le effigie de gli antichi, tanto con il lume dello intelletto considerate le loro attioni, prendendo que'begli essempi del vivere, che si convengono" (Le imagini, p. [4]).

[79] "Poca è la fatica di guardare, & di leggere, ma la utilitate, & il frutto è copioso, & grande, perche si vede, & istima quanto può la virtute, à che infelicitade si volga l'errore, di quale giovamento sia l'homente libero, & uno scelerato servo. & finalmente come niuno fugge la providentia di Dio nel ricevere le pene, ò i premi, ch'egli s'habbia meritato" (ibid., pp. [4]-[5]).

[80] Only occasionally did he counterbalance the representations with moral criticism (some of Nero's reverses depict courtesans, plunder, and the like).

17.

Jacopo dal Ponte, Portait of Two Hounds (Due bracchi ), ca. 1550. Commissioned by

Antonio Zantani in 1548, paid for 1550. Private collection.

tions was to return in a little literary composition of his, the "Dubbi morali del cavaliere Centani" — a brief contribution to a popularizing ethics organized into a pedantic series of questions and responses on temperance, abstinence, and honesty.[81]

In the last analysis Zantani begged any exegetical questions that might emerge from these exercises. While he could have "interpreted and made declarations about the reverses," Zantani wrote, he believed such an effort in many ways to be "difficult and vain" and so left this to the judgment of each individual.[82] Even this he turns to moral account, for true judgment is seen as an act of divination, the revelation of a stable reality whose truth is unassailable. After all, "it can easily happen that the contin-

[81] Zantani's "Dubbi morali" is found in Book II of the Quattro libri de dubbi con le solutioni a ciascun dubbio accommodate, published by Giolito (whose name does not appear on the title page) and ed. by Ortensio Landi (Venice, 1552), pp. 174-76. The volume is discussed by Salvatore Bongi, Annali di Gabriel Giolito de' Ferrari, 2 vols. (Rome, 1890-97; repr. Rome, n.d., 1:368-70. On Zantani's composition of "dubbi amorosi" for another volume edited by Landi see Muraro, Il "libro secondo," p. 382 (I have not seen the latter "dubbi").

[82] "Io poteva . . . forzarmi nella presente opera de interpretare, & dichiarire i riversci delle medaglie, ma riputando io tale fatica in molte parti essere & difficile, & vana, ho voluto lasciare al giudicio di ciescaduno questa cura, & pensiero" (Le imagini, p. [6]).

ual diligence of some students . . . may reveal fitting and true interpretations, [while] many others [are] sooner apt to guess than to judge the truth."[83] "The risk of error is very great," he cautions, "and the fruits dubious and few."[84] His preference was the wordless language of pictures and his pleasure the tasks of taxonomy: organizing the reverses into a visual chronicle, separating copper ones from gold and silver, and the like. Less verbal than many of his fellow patricians, Zantani nonetheless longed for the same moralized polity represented by good olden times and timeless old goods.

The moralizing tone Zantani adopted in Le imagini and in the "Dubbi" recalls many writers' emphases on Helena's virtue — a virtue that was mutually produced through encomiastic representations of her and through her own forms of social action. Like many Venetian noblewomen Helena seems not only to have stood for ideals of virtue but to have lived out her personal life in pious acts of charity. Toward the end of her life, on 22 June 1580, she organized such acts in a lengthy and detailed will inscribed by her own hand (Appendix, D). Following Venetian tradition she requested a burial "senza alcun pompa" in the same arch of the church of Corpus Domini where her father-in-law and husband were buried. For the rest she mostly specified distributions of alms: ten-ducat sums to various churches, institutions of charity, and to the prisoners of the Fortezza, altogether totaling one hundred ducats; ten-ducat dowries for three needy girls; all of her woolen and leather fabrics among "our poor relatives"; and the release of all her debtors.[85]

By comparison, Antonio's enactments of virtue took more public and symbolic forms. At the crux of his collecting activities was a family museum that bound civic virtue together with patrimonial fame. In keeping with this, the legacy of Zantani's work with medals not only presents him in the guise of moralist but shows him in the archetypal mold prevalent from the fifteenth century of the Venetian antiquarian engrossed by the ancient world and intent on preserving the past. In some forms, this sort of preservation could take merely fetishistic and sterile forms of

[83] "[M]olto bene possa avvenire, che la continova diligenza d'alcuni studiosi, accompagnata dal giudicio, & bello intendimento di varie cose, possa ritrovare acconcie, & vere interpretationi, & molti altri essere atti piu presto ad indovinare, che giudicare la verità" (ibid.).

[84] "[I]l rischio di errare è grandissimo, il frutto dubbio, & poco, & molto habbia dello impossibile per l'oscurità delle cose avolte nella longhezza, & nella ingiuria del tempo: percioche le cose dalla memoria nostra lontane sogliono seco recare ignoranza, & l'antichita guasta, & corrompe i segni di quelle" (ibid.).

[85] Helena's will resembles those of other patrician women in Venice, whose bequests emphasized private relations with neighbors, servants, and friends, charitable institutions, and bilateral and natal kinship relations over and above the patriline. Among studies that have dealt with this question, see Stanley Chojnacki, "Dowries and Kinsmen in Early Renaissance Venice," Journal of Interdisciplinary History 5 (1975): 571-600; Donald E. Queller and Thomas Madden, "Father of the Bride: Fathers, Daughters, and Dowries in Late Medieval and Early Renaissance Venice," RQ 46 (1993): 685-711, esp. p. 707; and (most importantly for the sixteenth century) Dennis Romano, "Aspects of Patronage in Fifteenth- and Sixteenth-Century Venice," RQ 46 (1993): 712-33, esp. pp. 721-23 on female testators. Romano distinguishes between a "primary system" of patronage, with objects as the product (as generated by commissions) and a "secondary system" of patronage with objects as the sign (as effected through donations and bequests). Wills, for Romano, formed central instruments for the enactment of secondary forms of patronage, not least because they were relatively public in nature. In Helena's case, they represent a prime documentary source for our knowledge of how such patronage ensured the female patrician's virtue and the salvation of her soul through the care of less fortunate social ranks and thus pulled her acts into a complex circulation of culturally encoded goods and favors between high and low.

collectionism. Yet most Venetian antiquarians did not simply accumulate items piecemeal but made systematic acquisitions of vases, numismata, engraved jewels, and other antique artifacts, organizing them as a means of honoring the ancestral home. This is the end that is consolidated through production of Le imagini, as affirmed by the prominent Zantani iconography that decorates its title page.

In the sixteenth century antiquarians increasingly complemented their domestic patrimony with portraiture. Titian's painting of Helena, now apparently lost, could well have been Antonio's commission, forming part of larger patterns of acquisition no longer visible to us.[86] Venetians often purchased Flemish paintings, thus paralleling the acquisitions of Venetian musical patrons.[87] Here we can begin to piece together the cult of Helena, the cultivation of northern polyphony (and painting), and the antique collectionism that in combination marked Antonio's world. All three constituted precious components in the patrimonial order. Objects distant in both time and place formed monuments to the breadth and power of his family estate, in which Helena was central as both image and property. It seems almost inconceivable that an interested party like Zantani, much accustomed to shaping the creative forces around him, did not have a hand in constructing the cult formed around his wife. How different would such constructions have been from a monument to his medal collection like Le imagini or a testimonial to his salon like La eletta? The allusive networks within which such encomia and commemorations existed — and into which dialogic modes drew their practitioners more generally — were animated by the complex exchanges of goods, favor, speech, and song that created value and fame.[88]

[86] Titian's portrait is not dealt with among the lost portraits taken up in the comprehensive catalogue of Titian's works by Harold E. Wethey, who apparently missed Aretino's reference to it; see The Paintings of Titian: Complete Edition, 2 vols. (New York, 1971), vol. 2, The Portraits. Vasari's portrait did have its genesis in a familial commission, but from Helena's brother Antonio Barozzi. Vasari's notebook records the portrait as follows: "Ricordo come adi 10 di marzo 1542 Messer Andrea Boldu Gentiluomo Venetiano mj allogò dua ritrattj dal mezzo la figura insu[;] uno era Madonna Elena Barozzi et [l'altro era] Messer Angelo suo fratello de qualj ne facemo mercato che fra tuttj dua dovessi avere scudi venti doro cioè scudi 21" (Il libro delle ricordanze di Giorgio Vasari, ed. Alessandro del Vita [Rome, 1938], p. 39).

On sixteenth-century collections that mixed antiques and portraits see, for instance, Logan's description, which matches Toscanella's representation of Zantani: "Two possible ancestors of the Renaissance art collection are the collection of family relics and memorials and the antiquarian collection. The first Venetian family museums in the fifteenth century were . . . of the former kind — collections of arms and banners and other family relics — and doubtless in such shrines to the family lares and penates many sixteenth-century portraits found a natural place. The evidence suggests, however, that the systematic collection of works of art tended to be more closely associated with the collection of antique objects"; see Oliver Logan, Culture and Society in Venice, 1470-1790: The Renaissance and Its Heritage (New York, 1972), p. 153.

[87] On antiquarianism in Venice and the Veneto see Lanfranco Franzoni, "Antiquari e collezionisti nel cinquecento," in Storia della cultura veneta, vol. 3, Dal primo quattrocento al Concilio di Trento, pt. 3, ed. Girolamo Arnaldi and Manlio Pastore Stocchi (Vicenza, 1981), pp. 207-66. For a good general discussion of the phenomenon, with analysis of certain Venetian collections described in Marcantonio Michiel's Anonimo Morelliano, see Logan, Culture and Society in Venice, pp. 152-59. Logan reports that three-quarters of Venetian antiquarians also owned foreign paintings, with Flemish ones predominating. He adds that in general "the number of Flemish works tended to be in proportion to the size of the antique collection" (p. 158), and suggests that some of this may be accounted for by the trade lines through which both were acquired.

[88] For a fine anthropological treatment of the politics and forms of commodity exchange in social life see Arjun Appadurai, "Introduction: Commodities and the Politics of Value," in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge, 1988), pp. 3-63.

Here we might return to our starting point: the anxieties over the fashioning and winning of fame revealed in the dialogics of print culture by which we mainly come to know the Zantani. These anxieties had been adumbrated two centuries earlier in Petrarch's own verse, which called attention to the poet through his amorous obsession and his paradoxical complaints over the appropriation of his lyrics by the common fold. Central to the Venetians' construction of fame, apropos, was Petrarch's devotion in the Canzoniere to the cult of a single woman, a woman now often transformed into real flesh and blood, given voice, and sometimes satirized as sexually available. In all such forms, conventional and inverted, Petrarch's lyrics still provided the Renaissance master trope for figures of praise. As many critics have been quick to point out, moreover, Petrarch's praise of Laura is at root a monument to his own literary creation and the creation of his own self, as symbolized by the poet's laurel (the wreath of poetic achievement) and embodied in the verbal kinship Laura and laurel are given in his lyrics. This idea subtends the now classic semiotic analysis of Petrarch's poetic strategy proposed by John Freccero.[89] In Freccero's words, Petrarch's laurel is "the emblem of the mirror relationship Laura-Lauro, which is to say the poetic lady created by the poet, who in turn creates him as poet laureate."[90] Restated in the balder terms of my analysis, what Petrarch demonstrated to later generations was not only how to praise others but how to make praise of others serve as praise of oneself. This idea is wedded to more recent notions of Petrarch's special role in early modern culture in establishing selfhood not just as an ideological site of subjectivity and autonomy but as a socially embedded site of agency and self-invention — "self-fashioning," as it has come to be called in the coinage of Stephen Greenblatt.[91]

Critics since Freccero have elaborated the importance Petrarch's covert strategies of self-exaltation and self-fashioning assumed for the lyric in subsequent centuries. One of the most provocative commentaries comes from Nancy J. Vickers in her essay "Vital Signs: Petrarch and Popular Culture."[92] Vickers's interest lies in the continuities between Petrarch's tropes and the tropes prevalent in present-day popular lyrics, a continuity she sees made possible by our technological capacity for wide-

[89] "The Fig Tree and the Laurel: Petrarch's Poetics," Diacritics 5 (1975): 34-40.

[90] Ibid., p. 37.

[91] I refer to Greenblatt's Renaissance Self-Fashioning: From More to Shakespeare (Chicago, 1980) but also to more exclusively literary statements on the matter, notably Thomas Greene, "The Flexibility of the Self in Renaissance Literature," in The Disciplines of Criticism: Essays in Literary Theory, Interpretation, and History, ed. Peter Demetz, Thomas Greene, and Lowry Nelson, Jr. (New Haven, 1968), pp. 241-64, as well as the general notions of individuality as a salient feature of Renaissance culture, as defined by Jacob Burckhardt in the nineteenth century. On Petrarch's specific role in this process see Arnaud Tripet, Pétrarque, ou la connaissance de soi (Geneva, 1967), Giuseppe Mazzotta, "The Canzoniere and the Language of the Self," Studies in Philology 75 (1978): 271-96, and most recently (and importantly), Albert Russell Ascoli, "Petrarch's Middle Age: Memory, Imagination, History, and the 'Ascent of Mount Ventoux,'" Stanford Italian Review 10 (1992): 5-43.

[92] Romanic Review 79 (1988): 184-95. For Petrarch's ambivalence about his appropriation by the common people see Vickers's analysis on p. 195 of a passage from his Familiari. Other studies locating Petrarchism in specific historical time and place that have influenced my recent thinking include those cited in n. 3 above.

spread reproduction of words and sounds. For Vickers, continuities within high lyric verse cannot alone account for the vast temporal and cultural dispersion of Petrarchan texts as material identities. They cannot account for what she calls "the multidirectional exchanges between high, middle, and popular cultures so radically enabled by the reconstitutions of the work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction."[93] Here Vickers speaks of the culture of late-twentieth-century rock music. Yet her observations on how radically dispersed themes are inherited and traded between different social strata resonate with my own. For like her I am interested in how repetitions of Petrarchan tropes served to make famous the objects idolized, as well to create their authors' fame. More specifically, I am interested in how Petrarchan tropes were recast in dialogic forms to fashion fame in a dynamic urban environment. This means an environment receptive to the mobility of a kind of "middle class," of which most professional musicians formed a part, and receptive to the phenomenon of entrepreneurship, in which Venice's many less-established immigrant patrons, as well as musicians, played a role. In the network of compacts formed between patrons and composers we see the dialectic mechanical reproduction formed with Petrarchan music and Petrarchizing words.