10.

The Vision States

A variety of uncommon physical states helped the Ezkioga seers to break the bonds of social class, gender, and age and enabled the seers to speak the unspeakable and express the inexpressible. The videntes (in Spanish) or ikusleak (in Basque) (those who can see, seers) saw things that the mass of spectators did not, whether blinding light, the Virgin, saints, Christ, the devil, or heavenly tableaux. Over time many of them also became "hearers" of divine messages, and some of them felt the divine touch. Often during the visions, believing spectators smelled heavenly perfumes.

I located references to the physical states of seers in about four hundred visions. This material reveals patterns for individual seers and a slowly evolving general model of how to have visions and what kinds of things to see. It reveals as well the attitudes toward unusual physical states of those who chronicled them and of the doctors and priests who diagnosed them. We are thus led to the highly polarized debate as to whether atypical states of consciousness are evidence for the supernatural. Positivist psychologists, spiritists,

and followers of Catholic mystics quickly incorporated the visions at Ezkioga into this ongoing argument.[1]

Two forums for this running debate were La Revue métapsychique and Études carmélitaines mystiques et missionaries.

People thought of visions and ecstasies as experiences that happened to saints, occasionally to religious in convents, but rarely to ordinary people like Bernadette or the children at Fatima; visions were definitely not a part of daily life. Devout laypersons may occasionally have had ecstasies. The contemporary poet Orixe described a repeated childhood experience in Huici (Navarra) when his grandmother would fall into a daze as he read to her the Way of the Cross on the balcony. Her eyes turned up and she seemed not to breathe. But none of the scores of elderly persons I talked to in the course of my research had experienced such a mystical encounter before the visions began at Ezkioga. One visionary about seventy-five told me he had known no seers before the events started. His only ideas about visions or ecstasies came from sermons about saints.

They would say here when friars came or in sermons that in such and such a place people talked with God, and that even today there are people who talk with God and so on. But we could not understand it. It is so hard to grasp. It is easy to say. But who speaks with God?

Yet there may be more in the way of a local tradition than I discovered. Trancelike states occurred in religious of both sexes; moreover, rural Basques read deeply in religious literature and many had kin in convents. In 1877 the Prophet of Durango, who proclaimed himself Saint Joseph, had visions of angels in his attic.[2]

Orixe (Nicolás de Ormatxea), "Amona," written 1896-1900; farmer seer, March 1983, pp. 18-19; for Durango prophet see Barandiarán, AEF, 1924, pp. 178-184. Basque visions of the dead or the vision of the prophet of Mendata in the 1870s seem to have been without trance.

In a number of places in Spain and Europe laypeople regularly enter into some unusual physical state. Shrines like El Corpiño (Pontevedra) attract persons who are afraid they are possessed. In southern Italy and Sardinia persons who think spiders have bit them perform a kind of curative dance. At the feasts of the Madonna dell'Arco near Naples and Santa Rosalia in Palermo pilgrims arrive in abstracted states. And at Echternach in Luxembourg pilgrims until recently entered a kind of trance through dancing. But in Europe in the early twentieth century the altered states that the church tolerated were isolated from everyday society; they took place behind convent walls or in remote cultural pockets. Only a few revered laypersons, like the German mystic Thérèse Neumann, bore witness to ecstasy, if at great physical cost.[3]

Lisón, Endemoniados; de Martino, Terra del rimorso; Gallini, Ballerina; Jansen, "Dansen voor de geesten"; Lewis, Ecstatic Religion; Rouget, Music and Trance. For therapeutic trance dancing by women throughout North Africa, see Jansen, Women without Men.

Yet a collective memory of trances in apparitions persisted throughout Europe and was maintained in shrines, legends, sermons, and prints. For the Basques Lourdes was the most obvious example. And it seems that the Ezkioga seers and organizers leaned first on Lourdes as a model for a liturgy, for an etiquette of how to act, and for physical symptoms of ecstasy.

The Role of the Liturgy: Priests, Seers, and Audience

Starting on the third day of visions, in July 1931, a kind of liturgy provided a context and meaning for the events at Ezkioga. Within this context seers came

forward in a variety of physical conditions, ranging from the unaltered, everyday state of the first girl, to the deep trances of Patxi, to what appeared to be total unconsciousness in others. The seers appear to have learned from one another and from those who paid attention to them, so over time their physical states converged. As the number and quality of the spectators waxed and waned and the liturgy evolved, so did the vision states.

As we have seen, the priest Antonio Amundarain of Zumarraga improvised the liturgy. He got the first seers to hold candles (like Bernadette at Lourdes) and recite after him the rosary in a small procession to the vision site on the Ezkioga hillside, and he had the onlookers recite the Litany with arms outstretched. The time of the seers' first vision—about 8:30 in the evening—determined the time for these prayers. What quickly evolved was a kind of orthodox ceremony, led by at least two priests, at an unorthodox time (after dark) and in an unorthodox place (a semiwooded hillside). Apart from the late hour, all of the other elements were fairly predictable. From the fifteenth century, at least, on the rare occasions when people had visions in the countryside, the townspeople would go there in procession. And no one thought it strange to say the rosary, for the words "Hail Mary, full of grace … Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners" were quite appropriate.[4]

For first days see Justa Ormazábal, Zumarraga, 10 May 1984, p. 2; and LC, 7 July 1931. For historical background, Christian, Apparitions, passim.

Doubtless Amundarain called on his experience at Lourdes. In the diocesan pilgrimage the year before "the zealous parish priest of Zumarraga, don Antonio Amundarain, recited the Rosary, alternating in our two national languages. The fifth mystery was prayed by all with arms outstretched in the form of a cross, with the bishop setting an example." As at the apparitions at Ezkioga a year later, the Basque hymn of farewell, "Agur Jesusen Ama [Goodbye, Mother of Jesus]," followed this rosary at Lourdes and many present wept.[5]

BOOV, 1930, p. 472.

The Zumarraga clergy organized the vision scenario in the first months. On July 7 they separated the two original child seers, praying a rosary simultaneously with each to check whether they were separately seeing the same thing; subsequently the priests confirmed the simultaneous vision to the crowd. After the visions were over and the children appeared to the crowd in a window, people applauded and wanted them to speak. So Amundarain recounted the details of the first week of visions and had the children recite three Hail Marys. On the next night his assistant Juan Bautista Otaegui led the rosary, and during the second mystery the prayers halted as Amundarain gave a running account of what the girl said she was seeing. During the Litany another girl interrupted the prayers, crying out "Mother, what do you want?" from the shoulders of her father.

It is not easy to describe the emotional jolts of faith that people felt in that impressive crowd of men and women. What sad groans! What humble words! What distress! What trembling! What tears of joy!… Hearts of

stone would have softened in that touching moment. How could one fail to weep in that happy moment of love?[6]

All 1931: ED and LC, 9 July; LC, 10 July; José Garmendia, EZ and ED, 11 July (quote); A, 19 July. For Santa María del Villar (Época, 16) Amundarain's account was a translation for those who did not know Basque.

Amundarain thereafter extended and fine-tuned the liturgy. On July 11 after the rosary and the Litany, a priest directed the crowd in the singing of a Salve. On July 12 after the five mysteries of the rosary, Amundarain asked the crowd (by then 25,000) to sing "Egizu zuk Maria [Pray for us, Mary]," One writer described this mission hymn as "the dear melody that our mothers put in each of our souls to invoke in times of importance the Mother of Heaven with the clean confidence of children." After the Litany Amundarain added seven Hail Marys in honor of the Seven Sorrows of the Virgin. He was applying time-proven techniques of parish missions to arouse repentance in the vision sessions. As on other nights, the seers punctuated the prayers with cries. La Constancia confirmed that the effect was "simple and grandiose, with an emotion that makes the soul swoon. If only for the benefits of this public fervor, one should go to Ezquioga."[7]

All 1931: LC and ED, 12 July; ED, 14 July; and LC, 14 July. For "dear melody" see Dunixi, ED, 18 July. For the liturgy at Oliveto Citra see Apolito, Cielo in terra, 41.

The ceremony enhanced the visions and the number of seers increased dramatically. After noting that on July 12 about one hundred persons had visions, the somewhat skeptical reporter of El Pueblo Vasco warned that the mood had become contagious.

Of the thousands and thousands of persons who come to Ezquioga, there are many whose temperaments, already excited by what they hear and read, are in a state of extraordinary impressionability that disposes them to a fit or a fainting spell as, in the midst of that impressive religious expectation, the almost fixed hour approaches people consider propitious for the apparition. So while these special circumstances continue, there will always be half a dozen persons who fall into trance and assure they have seen the apparition. But it is possible that there are also those who out of vanity or by imitation assure the same thing and even talk about it with a disorienting seriousness or with a suspicious good humor.[8]

PV, 14 July 1931.

Soon the crowd became a vibrant, collaborative chorus for the visions and a source of new seers. The group prayers became a kind of clock. Seers began their visions "during the second mystery," "at the start of the fourth mystery," "during the fourth mystery," "at the second Hail Mary of the fifth mystery," "at the beginning of the Litany," or "after all the prayers were over, when people were beginning to leave." And the seers or the holy figures they saw began to intervene in the ceremony and direct the crowd. On July 8 the ceremony was over by 9:45 P.M. ; four nights later it lasted until 11 P.M. because more seers interrupted the prayers. When a woman from Azpeitia continued to see the Virgin after the rosary on July 13, the priests led extra prayers and she reported that "the Virgin's face was happier, and [the Virgin] went down on her knees."

The next night a twelve-year-old boy who saw a panoply of holy figures—the Virgin, the Sacred Heart of Jesus, two angels, some male religious—noticed that a heavenly nun was saying the rosary with the people. What began with children seeing the Virgin as a distant divine figure became in two weeks a kind of joint mission session. Earthly and heavenly participants met at a junction of the two realms.[9]

ED, 14 July 1931, probably Juana Ibarguren of Azpeitia; for boy see LC, 16 July 1931.

El Pueblo Vasco again warned how easily these conditions could give rise to visions.

The ambience could not be more propitious for suggestion, and so, admitting, of course, the possibility of the supernatural, we should read these reports with great reserve, above all taking into account the age and condition of those who claim to have participated in these visions.

On the next day, July 16, people expected a miracle. El Día 's description of the atmosphere confirmed this warning:

The voice of the priest who led the prayers reached distinctly the entire field. A vast murmur replied religiously…. The moment was one of intense emotion, and not only religious emotion, but the expectation of the unknown, and an expression of anxiety or fear could be seen on many faces. The cry would go up. Where would it be? Everyone looked at his neighbor, and no one was sure of himself.[10]

PV, 16 July 1931, and ED, 17 July 1931; see also Gatestbi, "Ezkion zer? [What Happens in Ezkioga?]."

On the eighteenth of July, another day of expected miracle, seers periodically cut into the priests' prayers, and when these were over, few in the enormous crowd departed.

Everywhere there started up prayers of isolated groups, men and women on their knees with their arms in the form of a cross praying devoutly without anyone allowing the least lack of respect. Gestures and partial movements [of individuals] throughout the crowd indicated that the mysterious phenomenon was under way.[11]

All 1931: ED, 19 July; Luzear, ED, 21 July; PN, 19 July; Iturbi, EZ, 23 July. From these sources the liturgy on July 18 consisted of a rosary led by a priest and two or three youths, a hymn, two Litanies, Salve Regina Gregoriana, Hail Marys to the Seven Sorrows, the hymn "Egizu zuk Maria," then prayers dispersed through the crowd. Over the month of July the order of these elements varied.

By then the sessions of prayers and hymns began after the priests had demanded quiet and continued in what one newspaper called a "sepulchral silence." The seers interrupted the service during and after the prayers. A schoolteacher described the spontaneous part on July 19:

And here the marvelous, the eminently simple and moving part began: "Ayes" and isolated shouts here and there: strangled cries, loving questions to "Mother! Mother!" some serene and ingenuous, others anguished and with an indescribable tone of voice—wails, fainting, tears, pressing appeals for forgiveness and grace; alteration of the calm and silence around the seers.[12]

Martínez Gómez, VN and PN, 22 July 1931.

We saw that some of this "alteration of calm and silence" involved applause, enthusiastic shouts, and vivas to the Virgin, to Christ, to Catholic Spain, and probably to Euskadi, to Christ the King, and to Alfonso XIII.

Walter Starkie, the Irish Hispanist, described the mix of liturgy and visions:

The Litany in contrast to the rosary was recited in Latin, and right from the start I felt that curious sensation of collective excitement … as if the devotional excitement of those thousands and thousands of people had enveloped me and lifted my soul out of my body. Suddenly I heard a cry piercing through the buzzing rhythm of the Litany.[13]

S 132-133. For this mix at Oliveto Citra see Apolito, Dice, 218.

The visions and the prayers, the cries and the buzzing rhythms, created a single dramatic structure. On July 21, for example, the original girl seer saw the Virgin open her arms during the rosary and she saw her wave when the crowd sang farewell with "Agur Jesusen Ama [Good-bye, Mother of Jesus]." And a boy saw the Virgin pray the rosary with the crowd, passing the beads through her fingers, and he saw her smile and move her lips as if singing.[14]

Similarly, when Bernadette said the rosary at Lourdes, she saw the Virgin counting beads. LC, 22 July 1931, has the first mention of the Agur hymn. The press referred to "Egizu zuk Maria" more frequently, and of the hymn the canon Juan Bautista Altisent of Lleida wrote: "When ... a shrine is built here that all of Spain visits in enormous pilgrimage, this hymn will without doubt be the equivalent of the 'Ave' of Lourdes" (CC, 9 September 1931).

This boy seer began to have visions a quarter of an hour before the official prayers, and other seers imitated this kind of excursion from the liturgical perimeter. On July 23 a fifteen-year-old farm girl from Ormaiztegi also saw the Virgin before the prayers. She described the Virgin following the movements of the crowd in prayer and kneeling on a kind of stairway when the Litany began. The ceremony Amundarain had set up to contain the visions had been outflanked, and the visions thereafter often preceded the official program and almost always continued after it.[15]

PV, 24 July 1931, p. 2.

Amundarain thought of the prayers he led as collective atonement for the burning of religious houses in May. María de Echarri confirmed that the prayers addressed the hostile climate for Catholics in Spain:

No prayer against the Liberals precedes or follows the rosary. They pray, for sure, fervently and with many tears, for Spain, for the nation that is more loved when it is more humiliated and disgraced. They pray for those who persecute Christ; they ask for mercy for those blind with hatred, so they can see, repent, and be saved. In the prayers there is not a whit of anger or indignation. Mercy and forgiveness are the feelings expressed.[16]

Amundarain to A. Pérez Ormazábal, 25 July 1931, in Pérez Ormazábal, Aquel monaguillo, 109-110; Echarri, Heraldo Alavés, 25 August 1931. María de Echarri was at Ezkioga sometime in the preceding week.

But as we have seen the seers even more than the priests keyed the visions to the particular circumstances of Basque and Spanish Catholics, expressing on behalf of the Virgin what the priests would not have dared to say in public. The familiar prayers and hymns of the liturgy set a general tone of penance; the vision messages that erupted during the ceremony provided specifics.

At 5 P.M. on July 24 an Ormaiztegi teenager seer was the first to see the Virgin in daylight. Her vision was a relief to Amundarain, for many people had voiced unease at the nighttime appearances. Four days later Amundarain started the

night session earlier, at 6:30 P.M. Nevertheless, most of the seers did not have visions until nightfall, about two hours later.

Shortly after the rosary had ended, and with still some daylight left, a movement of suspense of the entire crowd lets us know that one of the phenomena that everyone is awaiting with feverish anguish has occurred. The light gets dimmer and dimmer until the hillside is completely dark. It is at this time that the cases of vision occur in greatest number…. No one is capable of describing the emotion one feels at this time.[17]

For day vision see LC, 25 July 1931, p. 2. Patxi tried and failed to have a vision at the same time (ED, 24 July 1931, p. 8). Ten days earlier Amundarain had organized a rosary at 6:30 P.M. to see if Patxi and others would have visions in daylight, but they did not. Quote from F. D., CC, 16 August, for 6 August. Similarly the canon Altisent, CC, 9 September, for 18 August, "It has just got dark ... the time for deep emotions has come."

The priests decided that if the visions were going to continue and masses of spectators remain in the dark, a liturgy the clergy led was better than freelance prayers in small groups. So in spite of the new daylight rosary, priests led others into the night. The original rosary had five mysteries in Basque and a Litany in Latin. Later people prayed the expanded version of three parts and fifteen mysteries. By August 18, because of the numerous pilgrims from San Sebastián, Navarra, and Catalonia, one five-mystery section was in Spanish. This formal service generally ended around 8:30 or 9 P.M. , but at least on some nights there were rosaries as late as the visions lasted.[18]

At Knock in Ireland in 1880 the priest switched to English from Gaelic as pilgrims came from farther afield; see Nold, "The Knock Phenomenon," 45. There were at least two and generally three five-mystery rosaries between July 29 and Ramona's wounding on October 15. I do not know if priests led all of them.

Up to the time of Ramona's wounding in mid-October, the seers continued to orchestrate the prayers, interrupting the official liturgy and expanding into the periods before and after it. A visitor described Benita Aguirre in the rain of July 27, "with a powerful and angelic voice, crying out repeatedly, 'Egizu zuk Maria gugatik erregu [Pray for us, Mary]' (the first line of the hymn), leading the immense multitude to get down on their knees and sing hymns to Mary and say repeatedly the Litany and the Salve." Another wrote on July 30 that a girl from Bergara asked the Virgin, "'Do you want us to pray?" The girl then "asks us to pray and all of us prayed fervently seven Hail Marys." On August 16 during the liturgy a young girl from Albiztur told the crowd the Virgin wanted them to pray the rosary with more seriousness and sing the Salve better.[19]

Visitor: Cuberes i Costa, EM, 5 August 1931; for girl from Bergara: N., "Anduagamendiko agerpenak [The Apparitions of Mount Anduaga]," 708; for Albiztar girl: Luistar, A, 23 August 1931.

In late July the hope for a great miracle waned and attendance declined from tens of thousands to under five thousand nightly. People began to come with a different attitude. No longer potential seers, they became spectators. No longer nervous, fearful, and excited at the prospect of becoming seers themselves, many came just to see the famous in action. At the end of July Walter Starkie wrote, "Poor Dolores, for many of those good people you are like Francisco Goicoechea—a purveyor of nightly stunts, and you act as a thriller for them." In early September a writer in El Liberal of Bilbao observed: "For several weeks now, people who go to Ezquioga no longer think they will see the Virgin; they go to see the seers, the ones who do not miss a day."[20]

S 148; Millán, ELB, 10 September 1931; also Txibirisko, La Tradición Navarra, 19 September 1931.

This shift in spectator attitudes had various causes. After two or three weeks the visions lost their novelty. Attendance from the immediate Basque hinterland declined, and visitors from farther away, less sensitive to the local mood, were

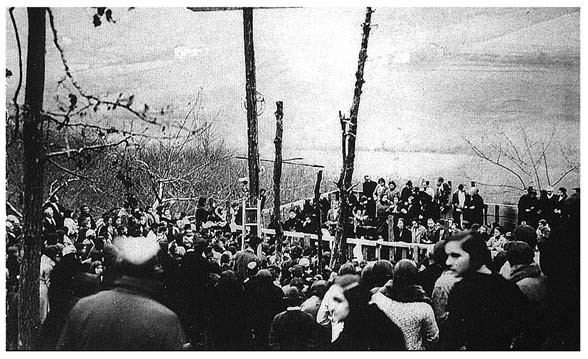

People watching seers in vision on stage, 27 December 1931. Photo by José Martínez

less likely to be seers. Starting in mid-July the press had begun to point to the unusual nature of the trances of some seers, like Patxi. In October Patxi put up the stage so that people could see the seers better. The platform was especially necessary when it became evident that miracles—trances, stigmata, or falling ribbons or medals—would happen to the seers themselves, not to the assembled crowd or the world at large. Priests led the nonstop rosaries from October 15 to October 20 from the stage, near the seers in a row, each seer in front of a helper. The seers were still facing the cross and holy trees where they saw the divine, but the people now faced the seers, not the cross or the trees. Many people had their backs to the Virgin.

After the end of October the cold and the rain and the negative press reduced the audience; at times all the spectators could fit on the stage with the seers. On a more informal basis, priests continued to lead rosaries, but Amundarain no longer organized them. When on December 26 the vicar general forbade priests to go up to the site, the prayers were led by seers, laypersons, or believing priests from other dioceses. Separate seers in vision led their cuadrillas up the hillside following the stations of the cross. Catalan pilgrim groups had their own prayer directors. But only during Holy Week 1932 and in September of that year did attendance climb once more into the thousands, with the kind of massed prayers so powerful in stimulating visions and moving hearts.

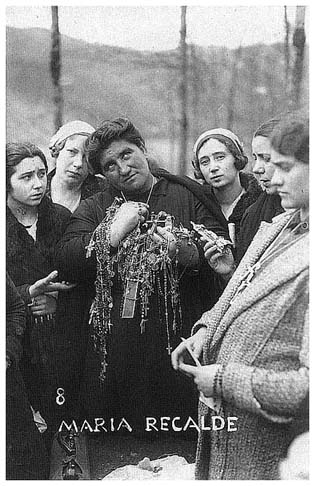

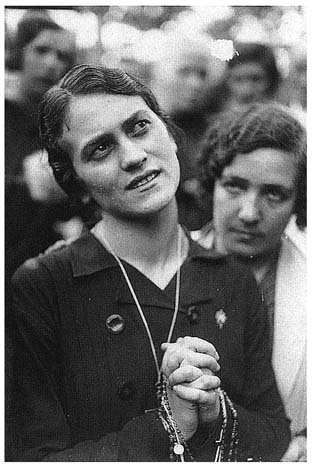

María Recalde in vision with rosaries, 1932. Photo by Joaquín Sicart

With a smaller audience, the seers could attend to the needs of those around them. Over the summer believers began to give the seers large numbers of medals, rosaries, and crucifixes to be blessed. A Catalan woman described Ramona Olazábal in early September:

One day, before the prayers began, one of those present gave this girl his rosary so she would have it in her hands during the ecstasy. She accepted it with signs of pleasure, but the idea spread and they did not stop calling her, each handing over to her a rosary…. When the rosary began, she stopped, knelt devoutly, and the ecstasy came very quickly. Afterward I asked her, "Did the Most Holy Virgin bless them?" "Yes, She blessed them," she replied.[21]

Delás, CC, 20 September 1931, about her visit September 3-5.

Image removed -- no rights

On the left, bent over by the weight of an invisible cross and kept from falling by two

men, a seer who is an elderly farm woman acts out the stations of the cross in vision,

May 1933. This seer will distribute as divine tokens the roses the woman in the

foreground carries. From VU, 23 August 1933. Photo by J.A. Ducrot, all rights reserved.

Photographs from the fall of 1931 and the spring of 1932 show the visionaries draped with devotional paraphernalia. As in the Barranca, most visions featured a moment when the Virgin would bless these objects. People who had connected medals with the holy trees now gave them to the seers to hold. The seers themselves had become the center of attention and a focus of miracles.

The believers took great pleasure in these divine tokens. A vision by Ignacio Galdós in November 1931 of angels receiving medals from the Virgin reflects the relation of believers to seers.

In her right hand the Virgin held silver rosaries, and in the other, many gold medals, which, raising her hand, she offered to all of us. The medals were all different, and I recognized only one, of Saint Anthony. Eight angels appear, and all kiss the scapular of the Most Holy Virgin, and then she puts a medal around the neck of each, and the angels, in their enthusiasm, like children, show them to each other and then soon disappear.[22]

SC D 102-103.

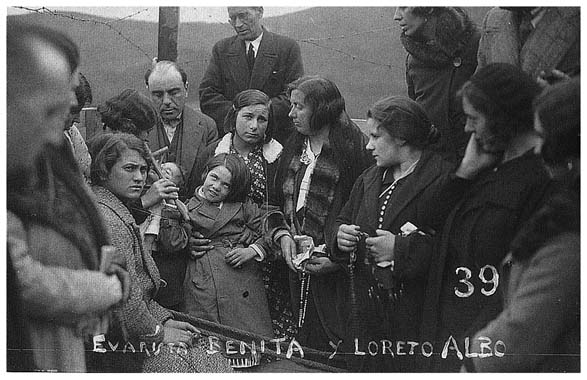

Catalans watch Benita Aguirre hold a crucifix for a boy to kiss, winter 1932. Photo by Joaquín Sicart

Medals and rosaries by this time had become a kind of medium of exchange that bound believers and seers together. In some cases, on instructions from the Virgin, the seers gave their own crucifixes, medals, or rosaries as gifts to believers; then the believers would buy others and give them in return.[23]

ARB 122, 139-140.

Visions included the obeisance of angels, who formed a kind of court for the Virgin, bowing, kneeling, and receiving orders. Similarly, believers kissed seers' hands, whether those of Ramona after the wounding or those of Benita when she returned their rosaries.We have also seen the flower become a divine symbol. Away from Ezkioga, some children in trance saw the Virgin in a flower or had visions of flowers or rewarded spectators with flowers. This distribution of flowers, easier in small groups, became common in the Ezkioga visions in 1932; thus blessed flowers, like blessed rosaries, were something that pilgrims took home as personalized talismans from the Virgin.[24]

For the language of flowers, of which this seems to be a refraction, Goody, Culture of Flowers, 232-253.

Another way to distribute grace was to press a crucifix to the lips of observers on the Virgin's command. From December 1931 seers in vision offered crucifixes to certain persons or invited certain individuals to come forward, giving them a

crucifix to kiss. Seers gave some believers the crucifix to kiss for an especially long time and ignored others altogether.

By distributing divine approval, the seers set up a kind of hierarchy of grace among the spectators. In the case of the Catalan expeditions, this new hierarchy sometimes reversed the order of the group. The factory worker José Garmendia and the humble farm woman María Recalde picked out the servants and the poorer members of the group not only for special favors but for notice as future seers. To be sure, they also singled out those who were chroniclers, like Salvador Cardús, Arturo Rodes, and Rafael García Cascón. Those they skipped were generally the few doubters or cynics in the expedition or onlookers obviously skeptical of or entertained by the events. In the Catalan groups these were the persons for whose "conversion" to Ezkioga members prayed. The later liturgies then, like those of the visions in villages away from Ezkioga, incorporated into the relations between seers and spectators a kind of theater of grace. Promotion, inclusion, conversion, or exclusion provided the tension in the plot.[25]

See ARB, passim, for descriptions of these events, for instance, pp. 110-111. G. Klaniczáy pointed me to an early equivalent in the way the ecstatic boy Henricus distributed kisses in "Legenda S. Emerici Ducis," E. Szentpétery, ed., Scriptores Rerum Hungaricum (Budapest, 1938), 2:452.

Vision States: How Others Saw Them

In about half of the Spanish lay medieval visions that we can document village priests or civil authorities instructed seers to return to the divine figure and request a proof. Some of the proofs they brought back were signs on their bodies or on those of other townspeople: a hand fixed as a cross; a mouth that would not open; wounds from a divine beating; sudden blindness; the prediction of imminent death from the plague of a seer or villager. We saw an echo of these signs when the judge could not undo Rosario Gurruchaga's hands, when Cándida Zunzunegui became supernaturally heavy after the police arrived, when Ramona and Luis had blood on their hands, and when the seers foresaw their own death.

In medieval accounts the physical state of the seer while having visions was not an issue. Only when laypeople began to doubt visions at the beginning of the sixteenth century do we read of a seer's claim to trasponerse , to be "transported so that she did not know or think she was in this world but rather the other." The authorities did not ask witnesses about these states, and indeed, most visions we know about took place without witnesses.[26]

Christian, Apparitions, 185-187.

By the time of the Ezkioga events, however, the new model of public trance-like visions applied, based presumably on Lourdes and ultimately on conventual mysticism. No longer did lay seers shuttle back and forth between the saint and the community after private visions. While their first vision might be private, they took along witnesses in subsequent sessions, and their state of consciousness while in vision was relevant to the process of validation. An altered state served as a sign. For inexperienced observers such a state might be proof that the visions were true. For seasoned clerics it might simply indicate that a seer was not

consciously faking. In any case, the old idea that contact with the divine left some kind of effect on the body resurfaced. Ezkioga believers refer to this state as being "en visión." Reporters from Basque newspapers, careful about prejudging the visions, generally avoided the word éxstasis , associated with sainthood, and only occasionally used the more neutral word trance .

Since at least the turn of the seventeenth century, when the Italian physician Paolo Zacchia described some religious visions as symptoms of mental illness, doctors took part in deciding whether visions were authentic.[27]

Marchetti, "La simulazione."

For some altered states might indicate not an ecstasy resulting from contact with the divine but another physical or mental condition. Animal magnetism, catatonia, epilepsy, hypnotism, hysteria, intoxication, mania, neurosis, obsession, somnambulism (which associated a trance with a dream state), and suggestion were diagnoses that experts offered at one time or another for seers at Ezkioga. Amundarain wanted to rule out alternatives like these, so in the first days he brought in the local doctor, Sabel Aranzadi. As with the doctors of the Bureau de Constatations at Lourdes in regard to miracles, Aranzadi's job at Ezkioga was to eliminate natural alternatives to ecstasy. His presence gave the commission the legitimacy of science.Aranzadi and other doctors took the pulses of the original brother and sister in vision and found them normal and steady. But since these children did not seem to experience any altered state, either during or after their visions, what they saw rather than what they felt was newsworthy. One of the reasons the public abandoned them rather quickly was the sheer simplicity of their experience. Rafael Picavea wrote of the boy, "The new seers have eclipsed him. He neither suffers moving faints nor falls into truculent pathological dreams."[28]

For pulse, all 1931: LC, 12 July; EZ, 15 July; ED, 17 July; ED, 19 July; Picavea, PV, 6 November.

The newspapers spent more time on those who showed more physical symptoms. The first of these was the chauffeur Ignacio Aguado, one of four successive youthful males who were skeptical about the visions and were then struck with visions themselves. When Aguado saw the Virgin during the rosary on July 4, he had been laughing and joking with friends. He felt something like a faint and fell down for about a minute. To observers he seemed unconscious, but as he described it, "I fell to the earth, but I did not lose my senses [el sentido ] and I continued to see the image." He had to be carried into a house and then driven back to Beasain. By one account he made a confession and became a churchgoer. The big play the press gave Aguado, side by side with the initial account of the child seers, indicates his critical role in supporting them. El Pueblo Vasco even inserted a cameo photograph of Aguado alongside one of the original seers' family. For most readers his conversion was part of the first account of the visions they read.[29]

All 1931: LC, 7 July; DN, 7 July; PV, 10 July (Aguado quote); A, 12 July (Aguado confession); GN, 17 July.

Patxi Goicoechea of Ataun was next. He fell down on July 7, after the regular prayers were over and he had made a joke about the Virgin. He had bounded to a rise on the hillside and pointed her out with a shout. On the advice of someone

nearby, he asked the Virgin three times what she wanted, and she said they should say the rosary. Those around him did so. Reporters described him then as keeping his eyes open but losing consciousness (sin sentido, kordegabeta ), as fainting (desvanecido ), as having a fit (pasmo ) or a rapture (arrobamiento ), or as remaining ecstatic (extatico ). His friends carried him down the hill. Like Aguado, he said, "I fell down in a faint but I did not lose consciousness; as I went down the hill in their arms she continued before me." By this time there was a first-aid room, and the doctors there found Patxi's heart working well. Like Aguado, he was shaken and someone had to drive him home. He did not recover fully until late that night, and for four days he did not eat, hardly slept, and was sad.[30]

All 1931: LC, 9 July; LC, 12 July; PV, 12 July (quote); A, 12 July.

In early July there were other seers experiencing trancelike states, but at first the press was interested not so much in the seers' partial loss of senses, which served as a kind of proof, but rather in their fall to the ground and the physical aftereffects. On July 8, the day after Patxi's vision, it was the turn of Xanti, a youth from Gabiria. He was allegedly stunned in mid-blasphemy as he raised his wineskin (or, in another account, as he rolled a cigarette). He had said there was no saint, male or female, who could knock him down, presumably referring to what happened to Aguado and Patxi. Three days later Aurelio Cabezón, an eighteen-year-old newspaper photographer who had been bantering with teenage girls during the prayers, suffered a similar shock. By his own account he saw the Virgin coming toward him, he gave a shout, and he fell to the ground unconscious. There doctors found his pulse racing. He regained consciousness in about half an hour. Afterward he was pallid, faint, thoughtful, preoccupied, and distracted. When he returned to take photographs on July 18, he had another vision during the rosary and was spooked again as the Virgin seemed to be coming toward him. He let out "a terrifying cry that echoed across the entire hillside" before falling unconscious.[31]

For Xanti see ED, 11 July 1931; Garmendia, EZ, 12 July 1931; and Cuberes i Costa, EM, 5 August 1931, citing Rvdo. Juan Casares's notebook. According to local people, Xanti stayed converted even though he worked in a factory. For Cabezón, all 1931: ED, 12 July; PV, 14 July; ED, 14 July; ED, 19 July.

This kind of initial "conversion by reaction," something like that of Saul on the road to Damascus, also occurred to a factory worker from Beasain. He allegedly said he would shoot his pistol at the Virgin if she appeared, and he promptly fell back into the arms of the church organist. It also happened to a taxi driver from San Sebastián, who allegedly made fun of the visions and fell backward and began to weep. It happened as well to Ignacio in Bachicabo in August, to a youth aged twenty-four named Nicanor Patiño, who made fun of the apparitions in Guadamur on August 29, and to Luis Irurzun in Iraneta in October. In 1920 a youth from Los Arcos had experienced the same reaction when he threw a coin at the Christ of Piedramillera. Under the pressure of the events, some of the most adamantly opposed, the most skeptical, were paradoxically those closest to belief. For Catholic newspapers these cases provided perfect object lessons for the Republic—they emphasized how divine power reduced proud men to weaklings. Therefore journalists emphasized not the altered state or the vision itself but the physical and psychological defeat.[32]

All 1931: factory worker (LC, 12 July), taxi driver (ED, 17 July; LC, 17 July; PV, 23 July; S 127-128). Patiño vision, 29 August, in El Castellano, 31 August 1931, Martín Ruíz, El Castellano, 2 September 1931, and León González Ayuso, Guadamur, 5 November 1976; for Los Arcos youth: Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 132-133, 140; see also Bloch, "Réflexions," and Goguel, La Foi dans la Résurrection, 419.

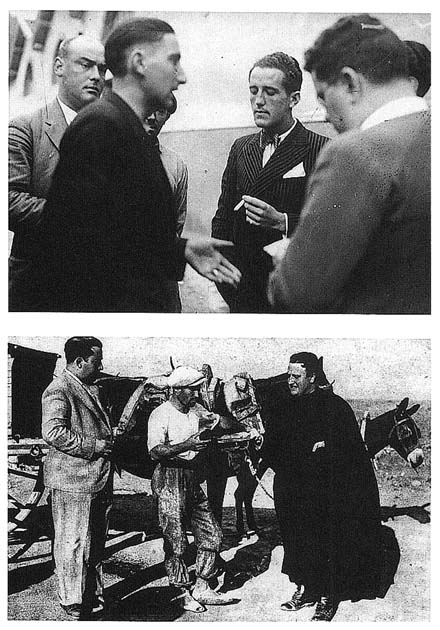

Attention to working men with "conversions by reaction": top,

reporters and chauffeur Ignacio Aguado in Legorreta, 9 July

1931 (photo by Pascual Marín, courtesy Fototeka Kutxa, Archivo

Fotografico, Caja Gipuzkoa, Donostia-San Sebastián); bottom, priest

and doctor with farm laborer Nicanor Patiño at Guadamur, 1931 (from

Ahora, 5 September 1931, courtesy Hemeroteca Municipal de Madrid)

As these males were achieving special prominence, women and children were also fainting right and left (the words used included deliquio, desmayo, desvanecimiento, síncope, pérdida de conocimiento ). Again, the final faint and aftershock seemed to be the determinative reaction, the evidence that the vision was real. For example, an eighteen-year-old female from Zestoa gave a great scream when she saw the Virgin on July 14 ("I could not hold it in"). She was not able to sleep the next night and was in an acute state of nervousness the next day.[33]

PV, 16 July 1931.

But El Día 's reporter was early in discerning a difference between genders. After interviewing a farmer still terrified the day after his vision, he wrote, "But not in all cases does the apparition have this upsetting effect, which seems to be more common among the men, who fall into faints or are semicataleptic." He mentioned two young women, Evarista Galdós and Juana Ibarguren, who "saw the apparition and far from being frightened ran after her, wanting to get closer and find out for themselves if the apparition was flesh and blood."[34]

ED, 15 July 1931.

Other descriptions of Benita Aguirre, Lolita Núñez, Ramona Olazábal, and the original sibling seers show that at least some women and girls welcomed the visions rather than feared them. This too was a pattern in the testimony at Piedramillera in 1920, where a woman saw the Christ smile each time she entered the church. The implication in these accounts seems to be that the women and children were more comfortable with the divine, while men were uneasy because of unconfessed sins and unresolved doubts.We may question whether a pattern emerged at all at Ezkioga or at Piedramillera. An unconscious selection by reporters and priests may in fact have prejudiced their reports. After the initial conversion reactions in July, the priests and doctors fished for more conversion reactions with their printed questionnaire: "What did you think about what was going on at Ezquioga with the visions? What mood were you in when you came to Ezquioga—devotion? diversion? or to make fun?" From Elgoibar a newspaper correspondent wrote that on July 16 four young men in their twenties had had visions. The note described an aftershock for one of them, who could not sleep that night and had to stay home the next day because he felt "abnormal and nervous." Of the other three it said nothing; presumably they slept well and went happily to work. Conversely, the press did not report some of the more traumatic visions of women because they considered the women hysterical. So our sources may be working from a script similar to the one used a decade before to describe those who saw crucifixes move.[35]

ED, 19 July 1931.

The stories of men converted by visions affected the debate on women's suffrage in the Constituent Cortes in Madrid. When the republican priest Basilio Alvarez and the republican pathologist Roberto Novoa Santos argued that women were hysterics subject to the whims of the uterus, the feminist Clara Campoamor countered that all the seers at Ezkioga and Guadamur were hysterical men. Newspapers on the Catholic right cultivated one misconception, that

only men had deep visions at Ezkioga, to show that irreligious men felt guilty. Campoamor used this misconception to refute another, that women were biologically irrational, born of the positivist left.[36]

Campoamor, DSS, 1 September 1931.

When the miracles of July 12, 16, and 18 failed to materialize, public attention shifted to Patxi. His visions were a prolonged spectacle of conversion (weeks after his first vision he would still cry out that he had been bad and he asked the Virgin to forgive him), and he was leading the way with exciting political messages and predictions of miracles.[37]

Lassalle, PN, 9 August 1931, "Mother, Mother, do not weep! Weep not, kill me, but forgive the others, who do not know what they do. Mother, forgive me, don't cry!"

He attracted attention in yet another way: in vision he appeared wholly insensitive to pain. When seeing visions he could talk, hear, and see those around him, but he could not, it seems, feel. As a result he became a kind of exhibit A, like a fakir. His local doctor from Ataun sometimes accompanied him to Ezkioga and other doctors and priests came to examine him in vision. They took his pulse, stuck him with needles and other sharp objects (including, by Bilbao doctors in 1932, a lancet under the nail of his big toe), burned him with a cigarette lighter, tested his pupillary reflex (he had none), and attempted with lights to provoke blinking (in vain). Occasionally he was excited and had what seemed to be convulsions, and once on his return to Ataun his doctor had to give him morphine to calm him. But he seems to have settled into a routine of visions on certain nights at certain moments of the rosary. Doctors described him in vision as catatonic or semicataleptic but in his normal life, out of vision, as sane and well.[38]For pulse see LC, 9 July; EZ, 14 July; S 135; Molina, El Castellano, 24 August; Altisent, CC, 9 September; B 177. For pricks see ED, 19 July; PV, 23 July; Lassalle, PN, 4 August; for lancet see J. B. Ayerbe, "Maravillosas apariciones," AC 1:2. For burns see Lassalle, PN, 4 August, and for pupillary reflex, ED, 18 July. For eyelid reflex see ED, 23 July; Molina, El Castellano, 24 August; Delás, CC, 20 September. For convulsions see PV, 23 July, and for morphine see Picavea, PV, 6 November. Clean bill of health from Dr. Pinto of Santa Agueda, B 380, and Dr. Carrere, AC 405.

This intense scrutiny culminated on August 1 when Patxi supposedly levitated. He declared that the Virgin had insisted, in spite of his objections, that he be elevated for seventy seconds. Although a day later the newspapers backpedaled and said that Patxi's friends simply felt his body become weightless, the idea stuck. Levitating was the stuff of the saints of cloisters, and Patxi became "Patxi Santu." A long and favorable article in Pensamiento Navarro on August 4 entitled "Apparitions? A Trip to Ezquioga" totally ignored the Virgin or her messages and dealt instead with Patxi and his strange vision states.[39]

"¿Qué ocurrió al joven Goicoechea?" ED, 2 August 1931, p. 2; ED, 4 August 1931, p. 5; PV, 4 August 1931, p. 3; Lassalle, PN, 4 August 1931; Rodríguez Ramos, Yo sé, 12-14. Micaela Goicoechea, age 24, who worked as a servant in Legorreta, allegedly levitated on September 6 (Boué, 148; R 47; Paul Romain in EE [April-May 1935]: 3), but two days later a reporter could find no witnesses (Txibirisko, La Tradición Navarra, 19 September 1931). At the end of September the rumor circulated in Bilbao that a boy had risen two meters, "and that because of all this and some other things the doctor was convinced of the truth of everything" (letter from a woman believer, 27 September 1931, private archive). Patxi supposedly levitated again October 17 (Easo, 19 October 1931, p. 8). An old-time believer (Ikastegieta, 16 August 1982) told me he himself saw a woman rise two meters in the air and two men grab her and bring her down.

The first step in any examination by the doctors was to take the seer's pulse. Almost any result was evidence for the truth of the visions for persons disposed to believe. For instance, doctors thought it exceptional when seers went through what were obviously highly moving visions with no change in pulse. The canon Juan Bautista Altisent of Lleida wrote of a boy seer: "I take the pulse of this child while he speaks to me, and it is completely normal. This is precisely, in the opinion of the doctors, the most remarkable thing of all: that in spite of the psychic state of the seer, his pulse keeps completely steady." Conversely, doctors thought it remarkable that Goicoechea's pulse ran so fast after a vision on July 11. Dr. Aranzadi told a reporter: "His pulse rate was fantastic. I was going to draw some of his blood because I feared his veins would burst." For this doctor Patxi's state of arousal demonstrated sincerity.[40]

Altisent, CC, 9 September 1931; Aranzadi quote, ED, 14 July 1931; Aranzadi said in PV, 23 July 1931: "The reality of his severe excitation and convulsions cannot be open to doubt."

Later, when doctors found some seers' pulses to be so slow during visions as to be imperceptible, they considered this phenomenon remarkable too. A professor from the Institut Catholique de Louvain in late August examined a teenage girl, probably Evarista, in vision. He listened to her heart and lungs, took her pulse, and examined her eyelid reflexes. He judged that the heart was beating irregularly, so he brought her out of her vision as a hypnotist would. A San Sebastián doctor examining Evarista in March 1932 found that her heart went three minutes without beating and considered her survival proof that the visions were supernatural. When believers tried to sum up the evidence of pulse rates during visions, they could not agree on a pattern. One Catalan doctor said the pulses tended to be normal, another maintained that they tended to be slow, weak, and sometimes even temporarily absent, and Burguera held that they were largely normal, although those of nervous persons tended to be fast.

As these examples show, doctors tried to apply science to these seers' states, but they had little experience and few standards. Thus they fell back on their inclinations, and since those who went to Ezkioga were more likely to be sympathetic, their findings tended to be favorable. The seers came to recognize doctors as allies. In vision Evarista turned to the San Sebastián doctor, saying, "The Virgin is very pleased by these scientific observations designed to illustrate and propagate the events at Ezquioga." Conversely, what the Jesuit Laburu saw of Evarista and other seers merely confirmed his prior skepticism. In the notes for his Vitoria lecture he wrote, "In any hypnotist or spiritist session, one can find identical phenomena. These things are common and very well known in suggestive phenomena."[41]

For Louvain see Tuya, "¿Apariciones?"; for Galdós, ARB 146; for pulse patterns, B 56-57, 124-134; for Laburu, L 40.

From late July observers stuck seers with pins and burned them—some on the neck, others on the face and on the arms. Baudilio Sedano recounted that when he stuck Benita Aguirre with a long pin, she turned and smiled benignly. A skeptical French doctor did the same to a fifteen-year-old boy. In these instances, the seers showed no sign of pain. Observers tested children in Navarra in similar ways.[42]

"Noticies de Badalona," EM, 19 September 1931 (burns); Baudilio Sedano de la Peña with Lourdes Rodes, Barcelona, 5 August 1969, p. 1; for skeptical doctor, Pascal, "Visite"; Antonia Echezarreta, Ezkioga, 1 June 1984, p. 12 (tests on Ignacio Galdós); Pedro Balda, 7 June 1984, p. 13 (French doctors prick Luis Irurzun); old-time believer, Ikastegieta, 16 August 1982 (use of needles in faces); El Castellano, 26 September 1931, p. 1 (use of light in eyes); Tuya, "¿Apariciones?" (hand over eyes); Celigueta report, ADP, Izurdiaga.

The pupils of the eyes of many seers, like those of Patxi, did not contract when exposed to light. And both skeptical and sympathetic observers mention seers who, like Patxi, did not blink during visions.[43]

B 57-58, 129-134 (pupils do not react to light); Millán, ELB, 9 September 1931 (young man does not blink when lighted match passed before eyes); Altisent, CC, 9 September 1931, on Benita Aguirre and again, CC, 13 September, on Patxi, who did not blink for half an hour in vision; for similar observations: Farre, Diari de Sabadell, 7 October 1931, on teenage girl; Juaristi, DN, 25 October 1931, on Unanu girl; and Bernoville, Études, 20 November 1931, on woman seer.

Starting in late July doctors and priests held a cloth or some other object in front of the seers to test whether the visions were "subjective" (if they continued) or "objective" (if they ceased). The objects blocked visions of some seers but not of others. Again, no one seemed to know what this information meant. In retrospect, one fact seems clear: the seers were in a variety of physical states.[44]Tests with interposed objects reported in PV, 23 July 1931; ED, 22 July 1931 (on girl); S 144 (on Lolita Núñez); F. D., CC, 16 August 1931 (on Benita Aguirre). Thérèse Neumann and seers in Belgium saw in spite of interposed objects, so their visions were classed as interior: Pascal, Hallucinations; on this test at Medjugorje see Apolito, Cielo in terra, 84.

Another proof used to validate the apparitions was the change of expression on seers' faces. A reporter for El Pueblo Vasco noted, "The great transformation in their faces … impressed us vividly, leading us to exclaim, "Something is going

on here!'" Both believing and skeptical spectators singled out the same seers, by no coincidence those whom Raymond de Rigné, Joaquín Sicart, and José Martínez from Santander later photographed the most. Canon Altisent wrote of Benita Aguirre:

The child has a normal kind of face, but at the moment of the apparition the face is so transformed as to become exquisite, something that cannot be described. Then I thought that if Murillo were alive now he would go there to seek the model for the faces of the angels in his inspired canvases.

Similarly, a Catalan woman wrote that Benita seemed "like one of the angels she is contemplating." Salvador Cardús saw the transformation in Ramona as "a reflection of the beauty of the Mother of God" on the seer's face, with "a sweet smile that could only be the Virgin's."[45]

PV, 17 July 1931; Altisent, CC, 9 September 1931; Delás, CC, 20 September 1931; SC E 31.

People also singled out Cruz Lete ("one of those whose face is transformed most angelically") and Evarista Galdós, whose expression was "incredible if she were not really seeing something extraordinary." The skeptical French doctor Émile Pascal also noted the change in Evarista's face.

Little by little her face lights up, she smiles and seems to be seeing a marvelous spectacle. For a half hour her features reflect expressions that are really very beautiful: beatitude, joy, piety, happiness, etc., one after another with an unheard-of intensity. Without exaggerating, one thinks when seeing her of the Saint Teresa in ecstasy by Bernini in the church of Santa Maria in Rome…. Monsieur de Rigné has obtained some remarkable pictures of her … but they give only a poor idea of the intensity and beauty of this ecstatic's expressions. Remember that Bernadette at Lourdes in her visions was as though transfigured. Just seeing her was enough to convince certain witnesses.[46]

Tuya, "¿Apariciones?" 625; Pascal, Hallucinations, 34-35, who cites Estrade, Les Apparitions de Lourdes.

But not all faces were beatific in visions. Some, like Patxi's, alternated between ecstasy and a thick, sleepy look: "During the phenomenon he has two phases, one of apparent ecstasy and another of sopor. When he returns from the latter to the former, Dr. Aranzadi exclaims, 'Look, look what an enormous difference in the lines of his face!'" Others did not look right at all. Several observers I talked to disbelieved the visions precisely because of the faces, presumably the faces not photographed. In Ormaiztegi a priest's sister said, "What faces! They had fear on their faces. If they were seeing the Virgin would they look that way? I cannot conceive it." Two elderly sisters from Ordizia said the seers in trance had "disfigured faces."[47]

Patxi about 6-8 August 1931 in Lassalle, PN, 9 August 1931; interviews in Ormaiztegi, 2 May 1984, p. 2, and with sisters in New York, 3 October 1981.

People saw other changes in the faces. Even skeptical observers noticed a sheen (brillo ) on the face of Luis Irurzun. And occasionally people remarked a special light like an aura or halo. The mother of Antonio Durán, a young lawyer from Cáceres, saw his face "illuminated, as if some kind of light emerged from his features." Arturo Rodes described the original boy seer from Ezkioga as if

Evarista Galdó's in vision, 11 March 1932. Photo by Joaquin Sicart

alight: "It was pitch-black and he seemed to shine like an angel that was adoring the divinity."[48]

Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 7 June 1984, p. 5, told me that Victoriano Juaristi remarked on the sheen on Luis's face, and Maritxu Güller also mentioned seeing it; for the transformation of faces, "Lo que ha visto un cacereño en Ezquioga," El Castellano, 26 September 1931, from Extremadura; and ARB 39.

A pilgrim from Catalonia noted as physical signs of the sincerity of a seer from Sevilla, Consuelo Luébanos, the bruises on her cheek from her fall into trance. But the absence of bruises from falls could be still another reason to believe. Two Catalans saw none on Benita Aguirre's face despite her fall, and they generalized, "Even heavy men like Garmendia, whose solid body falls hard and loud against the ground, have never received any injury as a result of such spectacular spills." All of these observations sharpened the public's awareness that many of the seers were in a special state while having visions.[49]

Luébanos in Cuberes i Costa, EM, 5 August 1931. Gratacós, "Lo de Esquioga," 17 Dr. Tortras Vilella of Barcelona commented: "I confess with perplexity that I never observed the least injury" (B 125).

During the summer of 1931 medical interest in the matter was intense. Within a week of the first report there were several doctors present, including the famous Fernando Asuero of San Sebastián. When seers collapsed on the hillside, a doctor

was generally available. Doctors accompanied some seers from their villages; periodically groups of doctors examined the seers together. As the vision states became news in themselves, so did the doctors, including two from Hendaye and the professor from Louvain. This medical interest reflected the importance of doctors at Lourdes and was characteristic of most other nineteenth- and twentieth-century apparition sequences. Rumor had it that Manuel Azaña, then minister of war, had sent Gregorio Marañón, the nation's greatest medical authority, to diagnose the visions on July 22. Patxi, by then well aware of his own exotic properties, said he would like to meet the doctor.[50]

For memoirs of a Basque doctor at Lourdes, Achica-Allende, Cuadernos. Asuero (1886-1942) reportedly assured children they would have no more visions. He had achieved world renown in March and April 1929 for his cures by stimulating the trigeminal nerve. See Barriola, "La medicina," 41-45; Sánchez Granjel, Médicos Vascos, 36-38; Barbachano, El Doctor Asuero; and ED, 12 January 1933, p. 12. On Marañón, ELB, 23 July 1931, and PV, 23 July 1931; S 138; Patxi in Rodríguez Ramos, Yo sé, 15. The San Sebastián priest Pío Montoya, 7 June 1983, p. 3, assured me that Marañón had been there.

The most active among the many doctors on the Catalan trips were Miguel Balari, a homeopath who had previously studied the Barcelona mystic Enriqueta Tomás, and Manuel Bofill Pascual of the Clínica San Narciso in Girona, Magdalena Aulina's personal physician and public defender. The close-knit Basque medical establishment kept its distance, and persons with cures they attributed to the visions could not obtain medical certificates. Not one Basque doctor was a public supporter, much less a seer. At most, some were involved collaterally.[51]

The prominent urologist Benigno Oreja Elósegui (1880-1962) provided Patxi with the use of a car, according to Laburu (L 14). Oreja was a confounder of the Clínica San Ignacio of San Sebastián and spent weekends and summers at his house in Ordizia, Aurteneche, "Vida y obra," 14-67. Patxi approached Oreja's brother Marcelino, the deputy in the Cortes, without success. The daughter of the doctor of Segura was a seer, as was the maid of the doctor of Ormaiztegi: PV, 25 July 1931; PN, 22 July 1931; and Luis S. Granjel, Salamanca, 2 November 1994.

At first the vision states intrigued the Zumarraga doctor Sabel Aranzadi enough that he pointed reporters to the most "interesting cases." He eventually ended by supplying some of the most telling negative evidence. Yet he was never absolutely sure that the visions were false. In later years he told his friends that in spite of all he knew he could not bring himself to throw away the bloodstained bandages of Ramona Olazábal. The president of the medical association of Gipuzkoa, the ophthalmologist Miguel Vidaur, helped Padre Laburu. But neither Vidaur nor Aranzadi took a public stand.[52]

On Sabel Aranzadi: Mate sisters, Zumarraga, 10 May 1984, p. 2. Vidaur when widowed became a Jesuit and went to China; Barriola, "La medicina," 19.

We have seen how in Navarra the psychiatrist Victoriano Juaristi, a kind of regional version of Gregorio Marañón, turned public opinion against the visions in the Barranca. In San Sebastián the only doctor publicly opposed was José Bágo, who remanded the seers to the insane asylum. Politics rather than a personal knowledge of the visions seems to have moved him. As far as I know, the pathologist and deputy in the Cortes Roberto Novoa Santos did not go to observe the Ezkioga seers, but his assistant, José María Iza, was at Ezkioga on 17 October 1931. Not surprisingly his diagnosis was that "all have the muscular rigidity, the lack of reflexes, and certain peculiarities in the pupil and the nostrils that indicate the cataleptic state characteristic of hysterics."[53]

On Iza, PV, 18 October 1931. Iza followed the misogyny of his mentor, Novoa Santos, who argued in the Cortes, 2 November 1931, against women's suffrage: "La mujer es eso: histerismo." Heliófilo in Crisol, 3 November 1931, quoted from a 1929 Novoa Santos book: "A woman is a child who has achieved full sexual maturity. The guiding force of her morphological and 'spiritual' distinctiveness is her ovary."

There was always the possibility that some of the seers were mentally ill, a danger to society and in need of treatment. In 1934 a doctor in Soria published the case history of a male patient and seer whose first vision—he saw the Miraculous Mary surrounded by lights—was in 1929. The Virgin told him to "Love charity and you will see the Father of the Poor." He gave his money away, spent some time with the Vincentian Fathers in Guadalajara, then went off preaching on his own in the Alcarria, Córdoba, and Granada. People called him "the crazy friar." Local authorities took him to a mental hospital in Córdoba,

where among other claims he said he had become an automobile driver by order of the Virgin. She chose him to transport the column of Our Lady of Pilar to the village of Villaseca in Soria, where the Last Judgment would be held. He also asserted that one day he would be pope.

This patient was ill in more painful and dysfunctional ways as well, and the doctor concluded that he was insane and a danger to society, with symptoms including weak-mindedness, schizophrenia, and paranoia. But he also pointed out that

there are many mentally ill persons like M. G. whom we come across in daily life, who work and have a social life, individuals who, if they run along in a rut without difficulties and without coming across obstacles that require a healthy mind to overcome get into trouble only when they run afoul of laws and legal codes.[54]

Nieto, "Sobre el estado," 698. I owe this reference to Thomas Glick.

Doctors, reporters, or the general public diagnosed none of the Ezkioga seers as obviously crazy. When studying the unusual and varied vision states, the doctors were observing persons who had every appearance of being mentally healthy, so they focused more on the phenomenon than its bearers. Even Laburu recognized the similarities of the trances at Ezkioga to those other nonpathological contexts produced and he steered well clear of their physical properties in his lectures. When he showed the film of mental patients after a film of the seers, he did so, I think, simply to sway the audience; in the text of his lecture he never suggested that the seers were mentally disturbed.

Whether they believed in the visions or not, those who went to Ezkioga did not think the seers' unusual behavior was the result of mental instability. Some considered rather that the seers' actions embodied the reigning social and political instability (what the count of Romanones, referring to Ezkioga, called "the religious hypertension that the Basque people have reached"). For the believers the dramatic states of the seers reflected the extreme reactions of the divine beings to the plight of Spain.[55]

Romanones made the remark to the prominent French writer Gaëtan Bernoville in the summer or early fall of 1931: Études, 20 November 1931, p. 464.

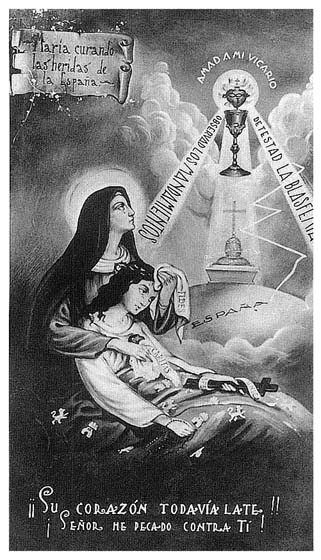

Thérèse Neumann: The Model for the Evaluators

The holy person who came to mind most when commentators searched for comparisons was the German mystic Thérèse Neumann of Konnersreuth in Bavaria. After a series of physical disablements and cures, in 1926 when she was age twenty-eight she began to have every Friday an extended sequence of visions of episodes of Christ's Passion. During the visions she seemed to weep tears of blood and had the marks of the stigmata on her hands, feet, and left side. Between episodes, in a trancelike state, she might answer consultations of pilgrims. Starting in September 1927, she claimed, she took no food but Holy Communion. The Sunday after Ramona's wounding, somebody distributed at Ezkioga large numbers

Drawing of Thérèse Neumann in vision. From El Pasionario, before March 1931

of an article on Neumann from the Madrid daily Informaciones . The Basque press that reported on Ezkioga carried lengthy stories about the German stigmatic and had in fact already done so before the visions. El Pasionario had been running a series of articles on her for more than a year when the visions started. Those looking for divine signs found that Ezkioga and Thérèse Neumann were part of a divine offensive against materialism and atheism.[56]

For the comparison with Ezkioga see Arteche, ED, 14 July 1931. Polo Benito, El Castellano, 11 September 1931, cited Neumann and Ezkioga, along with Lourdes, Fatima, and Guadamur, as elements of an "ofensiva de Dios." Tuya in "¿Apariciones?" suggested waiting for the truth of Ezkioga to come clear as a cardinal suggested waiting in the case of Neumann. Bishop Mateo Múgica contrasted Neumann's obedience with the seers' rebellion (Sebastián López de Lerena, "Relación de la visita que la vidente Gloria Viñals hizo al Sr Obispo de Vitoria el día 6 de septiembre de 1933," private archive).

For local news of Neumann see Basilio de San Pablo, "Manifestaciones de la Pasión"; "El caso asombroso de Teresa Neumann," ED, 3 April 1931, p. 12; Farges, Easo, 19, 20, and 21 October 1931; Bay, PV, 27 October 1931; "Un caso inexplicado, Teresa Neumann, la estigmatizada de Konnersreuth," Easo, ten-part series from 25 November to 8 December 1931; EM, 12 January 1932, p. 8; A, 9 October 1932, p. 2; for Informacìones Neumann article distributed at Ezkioga see Juan de Urumea, El Nervión, 23 October 1931.

News of this mystic reached Spanish newspapers in September 1927. Some clerical commentators warned against gullibility, referring to the recent cases of Claire Ferchaud and Padre Pio. Ferchaud's vision at Loublande during World War I found favor in the French church, but the Holy Office intervened and in March 1920 condemned the visions unequivocally. Padre Pio da Pietrelcina, an Italian Capuchin, experienced the stigmata in 1918. By 1920 leaves from a rosebush in his monastery and letters with his signature were used in healing in Spain. Spaniards visited him and wrote him for advice. The Holy Office issued five decrees against him starting in 1923, the latest in May 1931. Neumann convinced others, like a Capuchin who had been an early promoter of Padre Pio.[57]

Spanish devotion to Padre Pio in Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 91-92; and Diario Montañés, 13 June 1922, p. 1. Basilio de San Pablo, "Manifestaciones de la Pasión," 1930, pp. 58-62, cites articles in El Debate in September 1927 by "Danubio," in El Debate in September 1928 by Bruno Ibeas, in El Siglo Futuro in October 1928, and in ABC (Madrid) on 3 July 1929 by Polo Benito. Warnings about gullibility: Tarré in La Hormiga de Oro, 6 October 1927, and Gazeta de Vich, 15 October 1931, and Urbano, "Neumann, Rafols." Martínez de Muñeca, El Debate, 26 July 1932. El Pasionario held off reporting on Neumann because of the false miracles at Gandía in Valencia in 1918, the exaggerations at Limpias starting in 1919, and the case of P. Pio.

By the start of the Ezkioga visions Editorial Litúrgica Española in Barcelona had published three books on Neumann. In 1931 she was at the height of her popularity, living proof of the truth of Catholicism, receiving three hundred letters a day.[58]Spirago, La Doncella estigmatizada; Lama, Una Estigmatizada; and Alujas, Teresa Neumann. Herder published Waitz, Mensaje, in 1929, and "Els Fets de Konnersreuth" began appearing in La Veu de l'Angel de la Guardia in October 1930. For Neumann's popularity see M. Lecloux, "Une Conférence sur Thérèse Neumann," La Croix, 27 November 1931, p. 2.

Reports about her fit into an ancient tradition of fasting laywomen who serve as intermediaries for humans with the dead and with heaven, a tradition that continues to the present day in Spain.[59]There was a woman who supposedly lived only on the host in Montecillo, near Espinosa de los Monteros (Burgos) in the 1930s (Baroja, El Cura de Monleón, 146). In 1977 I heard of a similar young girl in the province of Orense, considered a saint for not eating, who had people lining up to visit her and leave alms until a doctor from Vigo administered a drug and she vomited octopus. Apart from the better known cases of holy abstinence in saints, studied by Imbert-Gourbeyre, C. Bynum, and R. Bell, there appears to have been a long and continuous folk tradition of "living saints" of this nature in peasant Europe. See, for example, the Austrian woman in Bourneville, Louise Lateau, 86, and for Asturias, Cátedra, This World, Other Worlds, 264-268.

Some of the enthusiasts for Ezkioga had been to see Neumann. The Bilbao religious philantropist Pilar Arratia found the visionary crucifixions at Ezkioga in January 1932 similar to those of the stigmatic, except they were without blood. The noted Basque clergyman and philologist Resurrección María de Azkue visited Neumann in September 1928 and on his return gave lectures about her; he seems to have been a discreet sympathizer of the Ezkioga visions. Neumann enthusiasts like Raymond de Rigné, Fernand Remisch, Ennemond Boniface, and Gustave Thibon spread news of Ezkioga in Belgium and France.[60]

For Arratia see Echeguren to Laburu, Vitoria, 20 January 1932; Azkue, La Estigmatizada, first published in Reseña Eclesiástica. See R 51, "an eminent priest who has seen Thérèse Neumann, assures that the revelations of Gloria Viñals will be more important"; he mentions Azcue a few pages later.

Father Thomas Matyschok, a professor of Psychic Sciences in Germany, gave lectures on Neumann in Pamplona in August 1932 and in San Sebastián in December. His experience with Neumann qualified him as an expert, so Juan Bautista Ayerbe took him to evaluate Conchita Mateos in vision. Matyschok found in the child the five key qualities he observed in Neumann: (1) she fell into ecstasy suddenly; (2) she was not aware in sight, sound, or intellect of what was happening around her; (3) she remembered faithfully and precisely what happened in the ecstasy; (4) she was insensible to fire, pricks, blows, and the like, and (5) she did not blink or move her eyes when struck by a powerful electric beam.[61]

VN, 3 August 1932, p. 8; LC and ED, 16 December 1932, and PV, the next day; J. B. Ayerbe, "Las maravillosas apariciones," AC 2:5.

Like Soledad de la Torre, Padre Pio, and other "living saints," Neumann was used as an oracle and a prophet. She seems to have worked in synergy with other sources of religious enthusiasm. I do not know if visitors asked Neumann about Ezkioga, but she did answer questions about Spain. Matyschok said that she told him that the Limpias visions were true and that it was the Christ of Limpias that she saw in her visions. Similarly, she told a priest from Zaragoza in September 1935 that she had heard of Madre Rafols's prophecies and that "a young man," whom the priest retrospectively identified with Francisco Franco, was working firmly for Christ in Spain.[62]

J. B. Ayerbe to Alfredo Renshaw, 6 October 1933, ASC; Antonio Gil Ulacia, a priest in Zaragoza, "Un caso inédito: A modo de prólogo," in Vallejo Najera, El Caso. Neumann was also used as an almanac. Diari di Vich, 10 September 1931, p. 3, said she predicted flooding from a great storm that month. In October 1931 she was said to have confirmed the apparitions at Marpingen; as in 1877 Louise Lateau also was thought to have backed these visions: Blackbourn, Marpingen, 167, 368.

People also used Neumann as a counterexample. Rafael Picavea sought to discredit the Ezkioga visions by describing "morbid" phenomena in which self-suggestion played a large part. He cited evidence that Neumann ate secretly and deceived herself as well as others in order to show that Ramona and other seers were equally open to self-deception.[63]

Picavea, PV, 20 November 1931.

Starting in the mid-nineteenth century, as psychology became more prominent, even among Catholics there was a kind of open season on religious ecstasy. A diagnosis of hysteria for Teresa de Avila was a major issue in Spanish publications appearing around her third centenary.[64]

Perales, Supernaturalismo, defended Teresa de Avila's visions, locutions, and divine raptures against naturalists like Maury but nevertheless diagnosed her as suffering from grand mal of Charcot (270, 338) and cited as certainties phenomena of spiritism and magnetism (285-297), which he attributed to the devil. Brenier de Montmorant, Psychologie des mystiques, 237 n. 1, gives other participants in the controversy.

The pathologist Roberto Novoa Santos proposed angina as Teresa's divine wounding. These were offshoots of an enormous French literature that sought natural explanations for trances, raptures, miracle cures, and stigmata. Orthodox Catholic psychologists spent much of their time refuting the new studies or denying their applicability to true visions.[65]Novoa, Patografia; he raised the angina issue in a lecture at the Madrid Atheneum, 20 November 1931. For French background see Herman, Trauma and Recovery, 7-28; Hilgard, Divided Consciousness, 1-14; Duchenne, Mécanisme de la physionomie, 145-154; Maury, Le Sommeil, 229-255; Godfernaux, Le Sentiment, 48-59; Charcot, La Foi qui guérit; Charcot and Richer, Les Démoniaques; Didi-Huberman, Invention de l'hysterie; Didi-Huberman, "Charcot, l'histoire et l'art"; Murisier, Maladies, 7-72; and Ribot, The Diseases, 94-103. Richet's Tratado de Metapsíquica was published in Barcelona by Editorial Araluz in 1923. For Catholic defense see Brenier de Montmorant, Psychologie des mystiques, 103-205; Mir, El Milagro, 2:712-13, 3:295-315, 361-400; Antonio de Caparroso, Verdad y caridad, 1932; and for a good bibliography see Gratton, DS.

Those defending Thérèse Neumann had to show how different she was from the mentally ill stigmatic studied by Janet in De l'angoisse à l'extase, or fromLouise Lateau, the most famous stigmatic of the previous generation.[66]

See, for instance, Robert van der Elst, "Autour d'une stigmatisation," La Croix, 24 December 1931, p. 3, and his "Stigmates" in Dictionnaire apologétique (Paris: Beauchesne). For Lateau see Imbert-Gourbeyre, Les Stigmatisés, vol. 1, and Curicque, Voces proféticas, 367-399. Bourneville, Louise Lateau, cites other works.

The Jesuit Juan Mir y Noguera charged that many of those challenging Catholic mysticism were Jews: "Yes, Jews who, not satisfied by making themselves lords of wealth, politics, and the press, scale the bastion of science to work more thoroughly their iniquity." The challenge had reached Spain. "Rationalism has infected not a few doctors in the peninsula, and the number of enemies of miracles and divine mysticism is still growing."[67]Mir, El Milagro, 3:399-400.

As far as I know, only one psychologist made a serious effort to examine the Ezkioga seers with "rationalist" theories in mind. The French doctor Émile Pascal was at Ezkioga sometime in early 1932 and two years later he published his attempt to "deoccultize" the apparitions, first in a specialized journal and then in a book entitled Hallucinations or Miracles? The Apparitions of Ezquioga and Beauraing .[68]

Pascal, "Visite" and Hallucinations. He also wrote "Une explication naturelle des faits d'Ezkioga est-elle possible?" EE 8 (October-November 1935). Pascal had already written Le Sommeil hypnotique produit par le scopochloralose (1928); Un Révélateur du subconscient: Le Hachich (1930); and La Question de l'hynoptisme (1930). Under the name Pascal Brotteaux he published Hachich, herbe de folie et de rêve (Paris: Editions Vega, 1934).

Pascal proposed that at Ezkioga the first seers' visions were based on stories about other apparitions and that the visions spread by imitative suggestion. As other instances he cited the Jansenist visionaries in the cemetery of Saint-Medard, an epidemic of possession at Morzine in the 1860s, the contagious effects of mesmerism, and American revival meetings. Similarly, the psychiatrist Victoriano Juaristi from Pamplona considered the Navarrese child visions an epidemic of neurosis like similar contagions in schools, hamlets, and entire regions; and the deputy and journalist Rafael Picavea compared the spread of visions to psychological contagion among women factory workers and to the seventeenth-century witch craze.[69]

Pascal, Hallucinations, 42-43; Juaristi, DN, 25 October 1931, p. 12; Picavea, PV, 14 and 20 November 1931. The treatise on crowd psychology by Rossi, Sugestionadores, 113-135, gave examples of group suggestion, including some Italian religious visions.

What interested Pascal especially was the psychic state of the seers. He suggested that the seers were

plunged into a light subconscious state, with a tendency toward a fixed idea. More precisely, the seers are plunged in a low-grade somnambulism, with all their spontaneous attention concentrated on the vision, as with a hypnotized subject under the influence of an intense suggestion. We would call this a light state. For there is missing here one of the characteristics of a deep somnambulism: amnesia upon awakening.

He pointed out the similarity of these seers to persons he had observed under the influence of certain drugs or light hypnosis: all were at least partially aware of what was going on and could remember their experience later. In this kind of half-trance they had contact with the external world and could answer questions from those around them: "The normal consciousness of the ecstatic is present, like a kind of spectator, at the apparitions provoked in the subconscious by the suggestions of the ambience."[70]

Pascal, Hallucinations, 45. See the similar, if cruder, analysis by Millán, ELB, 10 September 1931: "They 'see' their own thoughts, they 'speak' with the mental figure that their brain has lodged and given form, and they 'hear' words that their own 'ego' pronounces, according to the beliefs, feelings, or physical circumstances of the seer-sensitive."

Padre Burguera objected to suggestion as an explanation. He pointed out that many people went to Ezkioga wanting visions but did not have them,

while others who were merely curious or even skeptical did. Pascal countered with the psychological axiom that "instead of evoking the expression of the subconscious, voluntary and conscious attention paralyzes it and blocks its development," which is why those who wanted visions often did not get them. But, Pascal argued, "fear that the subconscious might erupt and the attempt to prevent it from doing so will often evoke it in sensitive persons," a process that would seem to apply to unwilling visionaries like our young male converts.[71]

Pascal, Hallucinations, 48, citing Coué; B 89-115.