PART III

THE METAPHOR OF THE MASK AFTER THE CONQUEST

11 Syncretism

The Structural Effect of the Conquest

It was almost to be expected that when the pre-Columbian world of Mesoamerica was confronted by the European world, when Moctezuma came face to face with Cortés, the mask would play a symbolic role in that confrontation of two worlds, each with its own spiritual assumptions. Confronted by the cross of Cortés, Moctezuma responded with the mask: different metaphors for different views of reality, each wonderfully expressive of a way of relating human life to the mystery of the eternal. These were such fundamentally different ways that the resulting conflict between the representatives of two of the world's great religions would never be fully resolved, for none of the possible resolutions could work. The fundamental differences made a full merger impossible; the realities of the Conquest dictated that the indigenous view could not prevail. But the eons-long, rich development of that indigenous view in the mythic vision and ritual practice of the peoples of Mesoamerica had entrenched it so firmly that it could never be destroyed by foreign invaders. The conquistadores prevailed physically, but the spiritual vision of the indigenous people remained intact. The result was the peculiar blending of Christian and indigenous symbols and ritual which continues to exist today among the Indian peoples of Mesoamerica.

When, thirty or so years after that meeting of Cortés and Moctezuma, the boy who was to grow up to be Fray Diego Durán came to Mexico City, he found himself in the midst of that unresolved conflict in "an unstable and motley [society]—two religions, two political systems, two races, two languages—in sum, two conflicting societies struggling to adapt to one another in a painful cultural, social, religious, and racial accommodation."[1] He was to spend his life in that struggle and in his darker moments came to doubt that he and his fellow priests were making much progress toward ending the conflict through the meaningful conversion of the indigenous population. In 1579, he wrote, "These wretched Indians remain confused. . . . On one hand they believe in God, and on the other they worship idols. They practice their ancient superstitions and rites and mix one with the other."[2] As he realized, they were fitting Christian concepts into the structure of their own spiritual vision.

How ignorant we are of their ancient rites, while how well informed [the natives] are! They show off the god they are adoring right in front of us in the ancient manner. They chant the songs which the elders bequeathed to them especially for that purpose ... They sing these things when there is no one around who understands, but, as soon as a person appears who might understand, they change their tune and sing the song made up for Saint Francis with a hallelujah at the end, all to cover up their unrighteousness—interchanging religious themes with pagan gods.[3]

He wrote that he was "extremely skeptical" that the indigenous religious calendar had been discarded in favor of the Catholic one and feared that he had "seen too much" to be optimistic about the possibility of true conversion.[4]

Those fears proved well founded. Four hundred years later, the "idolatry" he sought to stamp out still persists among indigenous groups, especially in the rural areas of Mexico and Guatemala serviced infrequently by visiting priests. Fairly near Mexico City in rural Tlaxcala, for example, an "extensive complex of basically pagan supernaturals, beliefs, and practices" still prevails,[5] and among the Maya of the Yucatán, the Chacs are still "the recipients of more prayers and offerings in a pagan context than any other supernatural being."[6] For

many Maya communities, in fact, the indigenous symbols of sun, moon, rain, and corn are still prominent.[7] An outsider visiting one of the Concheros dance troupes in central Mexico concluded that "they are carrying on the same practices that they had before the Conquest. They have not changed. . . . They are pagan, I tell you, purely pagan in their religion."[8] While his conclusion may exaggerate the "pagan" influence on today's belief structure and ritual activity generally and on the Conchero cult in particular, it is nevertheless quite true that pre-Conquest beliefs and practices persist, often within a fundamentally indigenous structure of belief.

Four centuries later there still beats in the heart of every Mexican a little of that blood which once stirred emotions before the rising sun, incarnate in Huitzilopochtli, or danced in the gay fertility of the harvests beneath the blessed rain of a Tlaloc, who continues to produce the divine corn .[9]

And four centuries later, masked dancers continue to dance their obeisance to the eternal forces of the world of the spirit which create and nurture life in this world. For them, the mask serves the same metaphorical function that it did for their distant forebears thousands of years before in the village cultures that began the long development of that indigenous Mesoamerican spiritual tradition. But to understand fully the culminating episode of that tradition and its relationship to the metaphor of the mask, we must first come to terms with the impact of the Conquest on native religion. We must ask, with Gibson, "What, finally, did the church accomplish?"[10] The answer is far from simple and must necessarily be incomplete; one must ultimately be willing to accept a certain degree of ambivalence, for paradoxically, as Hunt suggests regarding Zinacantecan symbolic structures, the old beliefs "have both changed profoundly and remained much the same, depending on the perspective. The symbolic structure has not changed (the structure is still there) and paradoxically it has changed (it became buried)."[11] And further complexity arises from the fact that what the church was able to accomplish varied from region to region. The indigenous framework of Maya religion, for example, is today more obvious, closer to the surface than that of central Mexico, a difference resulting from the fact that "the Aztec abandoned pagan rites and fused their own religious beliefs with Catholicism, whereas the Maya retained paganism as the meaningful core of their religion, which became incremented with varying degrees of Catholicism."[12]

Thus, syncretism, which William Madsen, following H. G. Barnett,[13] defines as "a type of acceptance characterized by the conscious adaptation of an alien form or idea in terms of some indigenous counterpart,"[14] rather than the replacement of the indigenous religion by the Christianity of the conquerors provided the means by which the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica were converted to Christianity, but even that end—which was not, of course, the goal the missionary priests soughtwas difficult to achieve in spite of the many superficial factors that might have seemed to make it relatively easy to accomplish. Conversion was particularly difficult at first because the repressive tactics used by the conquerors produced profound resentment and bitterness; the church had destroyed their gods and so for at least ten years, "the dominant Aztec reaction to Christianity was rejection."[15] The response given by "some surviving Náhuatl wise men in 1524 to an attack by the first twelve missionary friars on the validity of Indian religion and tradition" captures, in both its words and tone, that bitter resentment:

It was the doctrine of the elders

that there is life because of the gods;

with their sacrifice, they gave us life.

In what manner? When? Where?

When there was still darkness.

It was their doctrine

that the gods provide our subsistence,

all that we eat and drink,

that which maintains life: corn, beans,

amaranth, sage.

To them do we pray

for water, for rain

which nourish things on earth.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

For a long time has it been;

it was there at Tula,

it was there at Huapalcalco,

it was there at Xuchatlapan,

it was there at Tlamohuanchan,

it was there at Yohuallichan,

it was there at Teotihuacán.

Above the world

they had founded

their kingdom.

They gave the order, the power,

glory, fame.

And now, are we

to destroy

the ancient order of life?[16]

But punishment usually results in compliance, and because the friars meted out punishment for noncompliance and rewarded compliance, the behavior of the indigenous peoples gradually changed. But a "change of behavior does not [necessarily] involve acceptance of new values,"[17] and many of the conversions to the new religion were superficial.

That those superficial conversions took place is due in some measure to the numerous coincidences of belief and practice between the two religious systems. Durán, in fact, saw so many parallels that

he was convinced an evangelist had been there before the Spanish. But he was hardly pleased, as he also observed that "all of this was mixed with their idolatry, bloody and abominable, and it tarnished the good."[18] Some went even further.

Fray Servando Teresa de Mier, a Dominican friar from northern Mexico, was to create a furor such as had never before shaken the religious life of New Spain with his memorable sermon of December 12, 1794. In the Shrine of Guadalupe he revealed to his astonished listeners that the Aztecs had actually been a Christian people, though their Christianity had been deformed. They had worshipped God the Father under the name of Tezcatlipoca, the Son as Huizilopochtli, and venerated the Virgin Mary as Coatlicue.[19]

The existence of such striking coincidences of belief and practice contributed greatly to the syncretic adaptation of Christian forms to indigenous beliefs by allowing the basically different underlying assumptions to dictate practice that seemed Christian but was motivated by essentially indigenous beliefs. Thus, one must proceed cautiously in attempting to determine what the church was finally able to accomplish.

A striking example of this coincidence is the resemblance between Ometeotl, the supreme and abstract creator god of the Aztecs of whom no idols existed and to whom no ritual was specifically dedicated, and the Christian conception of God the Father, the relatively remote creator aspect of the tripartite Christian godhead. Similarly, Quetzalcóatl, the white Tezcatlipoca who died, rose to the heavens, but would return, could be, and was, compared to Christ in addition to more commonly being likened to Saint Thomas and sometimes Saint James. Both Christ and Quetzalcóatl had been sacrificed, both were sonlike aspects of the creator god, both existed in opposition to a dark aspect of the creative force, and both were seen as particularly representative of mankind. Among today's highland Maya, the parallels are perceived differently; they often conceptualize the trinity as three symbolic beings. One of these incorporates the entire Christian pantheon of gods, including God the Father, Jesus, and the saints, angels, ghosts, and virgins; a second consists of the earthly world as a whole including mountains and volcanoes; and the third is comprised of the ancestral dead.[20]

Such comparisons, of course, attempted to paper over the fundamental structural differences between the two cosmological views and the profound differences in the purposes of ritual within the two systems. Christianity saw an unbridgeable gulf between man in this world and god in the heavens; through death, the individual might find a union with the godhead, but god was not present in this fallen world. That separation of man and god was alien to the indigenous spiritual vision that held that one need only don the mask in the proper ritual context to allow the omnipresent world of spirit to emerge into this world. This world, then, was not only not seen as fallen but as sanctified: it was the visual manifestation of the underlying world of the spirit. While Christian ritual was primarily dedicated to the salvation of the individual's soul, that is, the movement of one's spirit after death from this fallen state to union with god, such a concept was alien to indigenous thought since union with the godhead was achievable through ritual. Indigenous ritual focused rather on man's reciprocation for the creation and sustenance of life by the world of the spirit, a conception foreign to the Christianity of the conquerors. As Marilyn Ravicz says, "The pre-Hispanic Indian had seen his relationship to the divine as one of dependence but as collaborative; . . they now had to see it as one of utter dependence upon a gracious two-edged Will of Love and Justice."[21]

But one aspect of the conquerors' religion was more easily assimilated than the others: the Virgin Mary, the symbolic giver and nourisher of life, was more similar to Coatlicue or Tonantzin, manifestations in indigenous thought of the nourishing earth that produced life, than was Christ to Quetzalcóatl or God the Father to Ometeotl. As is generally the case with Mediterranean Catholicism, in Mexico, even today, Mary is honored far more extensively than the Father and Son. She

is believed to have appeared in person to an Aztec commoner, Juan Diego, ten years after the Conquest of Mexico by Cortes, and to have imprinted her image, that of a mestiza girl, on the rough cloak or tilma of maguey fibers which he was wearing. This miraculous painting is still the central focus of veneration for all Catholic Mexicans .[22]

As Alan Watts points out, in that manifestation as the Virgin of Guadalupe, her "icon stands before the worshippers in its own right, representing the Virgin alone without even the Christ Child in her arms."[23] She is the mother goddess. Thus, Madsen claims that the "most important stimulus for fusion [of the two religions] was the appearance of the dark-skinned Virgin of Guadalupe which enabled the Aztec to Indianize the white man's religion and make it their own."[24] And still today the Virgin of Guadalupe, whose cult began immediately after the Conquest, continues to be worshiped as Tonantzin in many areas.

The two deities share many characteristics. Mary was the virgin mother of Christ, while the Coatlicue manifestation of the earth goddess similarly gave birth to Huitzilopochtli after having been impregnated by an obsidian knife that fell from the sky. In consequence, both were mothers of gods and invoked as "our Holy mother." Not

coincidentally, Mary was associated with the temple originally dedicated to Tonantzin on the hill of Tepeyac where the Virgin of Guadalupe first appeared to Juan Diego. But these similarities cannot obscure some fundamental differences as "the nature and function of the Virgin of Guadalupe are entirely different from those of the pagan earth goddess. The Christian ideals of beauty, love, and mercy associated with the Virgin of Guadalupe were never attributed to the pagan deity"[25] whose dual nature as earth goddess made her both creator and destroyer of life in the cyclical flux of the cosmos. Thus, the similarities between them enhanced the syncretic process, while the differences assured Mary's taking on a symbolic meaning she had never had in Spanish Christianity.

The two religions also shared the use of the cross to symbolize the meeting of the world of the spirit and the natural world. As we have seen, the Mesoamerican cross is actually a quincunx (fig. 4), a cross in which the center is of the same importance as each of the arms, which, in turn, represent the four cardinal directions and the four "cardinal" points of the sun's diurnal course. For pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, the quincunx symbolized the spatial and temporal dimensions of the universe and located its symbolic center. Another cross, this one known as the foliated cross, was an important symbol to the Maya, as we have seen in our discussion of the symbolism of the lid of the sarcophagus of Pacal, ruler of Palenque, and the ceiba tree, as its equivalent, similarly marked the center point of the universe with its roots penetrating into the world of the spirit below and its branches reaching into the spiritual realm above. Significantly, Cortés "stamped the sign of the cross on the ceibas which he found along his route" in the Maya area and "suggested adorning the Christian cross with branches and flowers, therefore presenting to the Indians the precise image of the mythical foliated cross, symbol of life and center of the universe" they had always revered. In such ways "the syncretism of the Christian Holy Cross with the mythical tree of native theogony came into being." After identifying that tree as the symbol of "the support of the universe," Salmerón explains that

the Mexican of pre-Conquest times, like today's Indian, in order to find security and to bind himself to that which is sacred, constructed his home in the image and likeness of the universe as he conceived it: square in form and, at its summit, the reference to the tree which sustains it. When the evangelizer presented the Christian cross to the natives as the protector of man-In Hoc Signo Vinces—he was saying nothing strange: transposed, the cross was the same symbol that had protected these people since early times.[26]

The cross, then, was yet another indication that the symbols of the past continued to give meaning to the present, "ordering reality simultaneously in the shape of the root metaphors of the old quincunx and the new cross."[27]

Hunt sees that conflation of the two crosses and the idea of sacrifice for which both stood as central to an understanding of the syncretic merging of the two religions.

Why then did the Mesoamerican peoples not adopt the codes of Christianity clearly and purely or completely reject one symbol system or the other? This was not necessary. The marriage of the old and the new was an easy one to arrange. To be converted they had only to reject one single major ritual parameter, that is, to change from actual human sacrifice for the maintenance of the social-cosmic order to symbolic human sacrifice, in the most human figure of Christ on the cross. Obviously, the cross itself, so similar in design to the prehispanic quincunx, imbued both the old and the new iconographies with the same aura of received sacred truth.[ 28]

Although Hunt may oversimplify the essential problem, it is surely true that the Indians considered the crucifixion and violent martyrdom of Christ, as well as that of many saints, symbolic of human sacrifice but experienced no feeling of guilt, sadness, or repentance in connection with that sacrificial death. To the Indian, it, like pre-Columbian human sacrifice, was a reciprocal necessity in the cyclical flux constituting the eternal and universal order of things. Death was necessary so that rebirth might occur. Thus, the image of sacrifice might be the same, but the meaning of that image was profoundly different as the significance of the native symbol never changed.

Precisely that syncretic mode of apprehending spiritual reality can be seen in the Maya view of sacrifice, the supremely important ritual activity through which man offers his substance in reciprocation for the sustenance of his life by the world of the spirit. Interpreting the crucifixion as another version of human sacrifice, the Maya continue to "pray to the cross as a god of rain"[29] and thus unite the central symbol of Christianity with the central idea of indigenous Maya thought. Landa realized very early that the fusion of the idea of heart sacrifice with the Christian crucifixion was evidence of continued paganism among the Maya, but as Thompson points out, it was only through this connection that Catholicism could have had any meaning in the indigenous cultural context. What was "incipient nativism" to Landa[30] was "meaningful acculturation to the Indians."[31] And the rituals through which the now-symbolic sacrifice is rendered to the world of the spirit continue to be scheduled according to the indigenous calendar in many Maya communities. In the Chiapas villages of Chamula and Zinacantan, for example, the ancient solar calendar is still used both to regulate ag-

ricultural activity[32] and to determine the dates of religious festivals.[33] For the Maya, "the revelations of time are still tied to the destiny of man"[34] but now in a syncretic way.

Still another similarity between the religious practices of conquered and conqueror can be seen in the pre-Columbian personification of the gods in small idols similar in function to Spanish santos. Perhaps encouraged by this practice, a number of associations were made between the old gods and the Christian saints. Tlaloc, for example, was sometimes associated with Saint John the Baptist and Toci with Saint Anne. In fact, "there are saintly counterparts for nearly all the native deities, which are either mere additions to the native religions (existing only in name) or represent the beneficial aspect of the deities with whom they are paired."[35] Of all the coincidences we have enumerated, the association of idols and saints probably persisted longest and had the greatest impact on the syncretic process since in accepting the community of saints as "a pantheon of anthropomorphic deities,"[36] the Indians were able to see each of them as a particular manifestation of the undifferentiated world of the spirit, a particular manifestation that served a particular ritual purpose in much the same way the multitudinous "gods" of pre-Columbian spiritual thought had functioned in ritual. Before the Conquest, each village had its own patron deity whose idol was ritually adorned with robes and jewels and presented with offerings; after the Conquest, each adopted a Catholic patron saint whose image was similarly adorned.[37] Little changed except the image; the underlying structure remained intact. Religion continued to provide "an explanation of the ordering of the universe, a channel for dealing with the supernatural forces of nature."[38]

Specific examples of the connection between "pagan" idols and santos abound. Durán noted that even after fifty years of contact with Christianity, the Indians were hiding their idols in church structures. And the association of idols and saints was still so strong in the seventeenth century that the worship of Catholic saints was called idolatry by Jacinto de la Serna, "who observed that some Indians thought the saints were gods."[39] "In 1803 one entire town in the Valley of Mexico was found to be worshipping idols in secret caves."[40] And even as late as the 1940s, the churches were kept locked in some Mixe communities so that priests could not interfere with the townspeople placing idols on the altar alongside the saints; for the Mixe, the church was simply another shrine.[41] The santos were generally worshiped in ways very closely related to the earlier indigenous worship, and consequently the religious fiestas still held for Christian saints have many of the pre-Hispanic elements of those held earlier in honor of various "pagan" deities.[42]

The two religions were superficially similar not only in their symbols, however; remarkable coincidences in their ritual practices also encouraged syncretism. Both, for example, had rites of baptism, confession, and communion. As Coe notes,

The Spanish Fathers were quite astounded that the Maya had a baptismal rite. . . . [During the ceremony] the children and their fathers remained inside a cord held by four old and venerable men representing the Chacs or rain gods, while the priest performed various acts of purification and blessed the candidates with incense, tobacco, and holy water.[43]

Among the Aztecs after the Conquest, the baptized infant often received a Spanish first name in honor of a Catholic saint and an Aztec second name honoring an Aztec god, both selected according to the day on which the child was born; the Christian name was determined by consulting the Catholic calendar while the Aztec name came in traditional fashion from the tonalpohualli.[44]

In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, ritual confession was related both to Tezcatlipoca, whose omnipresence enabled him to see all, and to Tlazolteotl, a manifestation of the female earth goddess known as the "filth eater" since the earth received everything. Confession could take place only once in a lifetime, and therefore the moment for it was carefully chosen. The penitent confessed his sins to a priest who was bound to secrecy; the confession was solely for the deity for whom the priest acted as agent. Then the priest, according to the severity of the sin, set a penance that, once accomplished, provided immunity from further temporal punishment. Durán explains that the confession was "not [always] oral as some have claimed,"[45] which he deduced from the fact that when he heard the Catholic confessions of Indians, they often brought pictures of their sins, evidently in the style of the codices. Although the modes of pre-Columbian confession varied somewhat from area to area—among the Zapotecs, for example, there were annual public confessions while the Maya might confess to family members in the absence of a priest[46] —the correspondence of all these practices to those of the Christian confessional was remarkable. It is little wonder that Durán was led to conclude that "in many cases the Christian religion and the heathen ways found a common ground."[47]

He was amazed as well by similarities in the rite of communion fundamental to both religions as each prescribed the ritual consumption of a sacrificed god. While "the Catholics drank wine and swallowed a wafer to symbolize their contact with the divine blood and body of Christ, the Mexica consumed images of the gods made of amaranth and liberally annointed with sacrificial blood."[48] The dough that formed those images was known by the Aztecs as "the flesh of god,"[49] a ritual substitute for the flesh of sacrificial victims who

had become gods but a substitute paralleling remarkably the Christian idea of transubstantiation. Other similarities in ritual practice existed as well: both religions accompanied ritual by the burning of incense in sacred places, and the priests who conducted that ritual in both cases "chanted, wore elaborate robes, made vows of celibacy, lived in communities ... and wore their hair in a tonsure."[50] Pilgrimages to especially sacred places played a major part in both. In fact, pre-Conquest pilgrimage centers, such as the one at Chalma, soon became, and remain even today, Catholic pilgrimage centers. But while these similarities helped to make the superficial transition between the two religious systems relatively easy, beneath the surface they had the opposite effect. They allowed indigenous meanings to remain attached to apparently Christian ritual behavior. Coupled with the deep resentment generated by the displacement of indigenous priests and ritual practice, this retention of indigenous belief did much to counteract the superficial success of the syncretizing process.

In addition to the many coincidences that encouraged the syncretic process, the Spanish themselves helped to keep the native concepts and customs alive by consciously using those coincidences in belief and practice as a means of making the doctrine and practice of the church intelligible to the natives. We have already noted that Cortés, no doubt consciously, confounded the Christian and native crosses among the Maya by slashing crosses into sacred ceiba trees and by permitting Christian crosses to be adorned, a practice that continues today, thus contributing to their confusion in the indigenous mind with the foliated cross that symbolized the tree of life. Similarly, he allowed Aztec idols to remain in the temples side by side with the crosses he had erected. And this confusion of symbols occurred in the communication of doctrine as well. For example,

in order to make the natives understand the meaning of the Christian heaven, the catechizer made use of the description of the Tonatiuh-Ichan (House of the Sun), the place where warriors killed in battle dwelled, or those who were sacrificed to the gods. These souls accompanied the sun . . . [and] returned to earth in the form of precious birds with red feathers, to suck nectar from the flowers.[51]

This same imagery can also be found in post-Conquest poems with angels taking the place of the warriors.[52]

The Catholic ceremonial calendar similarly encouraged the syncretic fusion of the two systems of ritual. As we have shown in Part II, the charting of the orderly movement of time was of great symbolic importance to the peoples of Mesoamerica. The calendar revealed the workings of the spirit, and the ceremonial cycle regulated by it was therefore ordained by the gods. Thus, it is not surprising, as Durán observed, that the particular day on which a Christian festival fell played a large part in determining the importance attached to it by the native populace and the enthusiasm with which it was celebrated. He noted that if the date had an important relationship to one of the indigenous gods, the feast was celebrated with much more joy, "feigning that the merriment is in honor of God—though the object is the [pagan] deity."[53] Even today, the pre-Columbian 260-day sacred calendar with named and numbered days persists in scattered places, especially among the Maya, and "time continues to be calculated and given meaning according to the ancient methods."[54] As will be seen in the discussion of the masked ritual involving the tigre and the pascola, such coincidences between Christian and indigenous ceremonial calendars are widespread even in areas where the indigenous calendar, as such, no longer exists. The tigres dance on days consecrated to the patron saints of the villages, but these days happen to fall at the proper time for rain-propitiating ritual. The Yaqui and Mayo celebrate the resurrection of Christ after the somber period of Lent, but their ritual makes clear that they are celebrating the rebirth of life in the agricultural cycle as well. Throughout Mesoamerica, the indigenous population continues to lavish its ritual attention on those Christian festivals that coincide with the important points of the indigenous ceremonial cycle.

The syncretic fusion of religious forms can also be seen in the continued use of indigenous sacred places as pilgrimage centers and places of worship. Cortés began this process when, during the Conquest, he decided that "in the place of that great Cue [pyramid] we should build a church to our patron and guide Señor Santiago" and built the cathedral dedicated to Saint James on the site of the Temple of Huitzilopochtli.[55] This construction at the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlán which equated the Aztec god of war with the saint who was the patron of the Spanish forces was to be followed by many more churches throughout Mexico which would similarly relate an indigenous god to a Christian deity or saint. According to Rafael Carrillo Azpeitia,

The conquerors used the pyramids as bases for their churches, thus taking advantage of the symbolism that represented the occupation and destruction of the temple of those people who had resisted the victors. Old places of worship were consecrated to the deities of the new religion. The cave of Oztoteotl was dedicated to the Holy Christ of Chalma; the church of Our Lady of Los Remedios was built on top of Mexico's most important ancient shrine, the pyramid of Quetzalcóatl in Cholula; in Tepeyac, at the northern edge of

Mexico City, the basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe was constructed, on the site where Tonantzin (Our Mother) had been adored.

He goes on to relate this particular impetus toward syncretism to the others we have discussed.

In the same way that the ancient temples and pyramids were used as bases for new sanctuaries, the spiritual catechists used certain customs and rites as a basis for the religious conversion and the subjection of the Indians to the power of the Crown. This syncretism is defined clearly by Solórzano y Pereyra, when he says about the Church: "Convinced that it would not be easy to deprive the heathens of their ancient customs immediately, and after having considered well, [the Church] decided to leave them their customs but call them by a better name."[ 56]

From our point of view in this study, there was no more important custom "left" the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica than the tradition of masked dance.[57] Nowhere is the Spanish practice of allowing native customs to remain while calling them by "better names" clearer, and no set of customs shows more graphically the complexity of the syncretic process. It can be said generally that the interruption by the Conquest of the steady development of Mesoamerican spiritual thought and the ritual based on it led to the existence in colonial and modern times of three types of masked dance among the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica: those dances introduced by the friars which have European forms and use European-style masks, those that substantially retain indigenous traditions and use masks derived from pre-Hispanic sources, and those that demonstrate a thorough fusion of the two traditions and a corresponding fusion of mask styles.

These, of course, are "ideal" types; in fact, every dance and folk drama contains both indigenous and European elements. In even the most clearly indigenous of masked dances, such as the Danzas del Tigre , which continue the association of the jaguar with rain and which will be discussed below, there are European elements, and even the most European of dance-dramas with the most European-appearing masks contain clearly indigenous elements. And in some masked dances, such as the Yaqui and Mayo pascolas, the indigenous and Christian elements have become so interrelated that they can no longer be separated. But it is significant that all of these dances—from the European to the indigenous—are today performed by Indian dancers in Indian villages. Where Indian and Ladino communities coexist in rural villages, it is the indigenous community that performs the masked dance-drama, which is very often regarded by the Ladinos with the scorn with which they generally regard Indian customs. The millennia-old Mesoamerican impulse to don the mask in ritual is still carried on even by those ritual performers who wear the most European of masks, masks that are generally quite realistic depictions of human features rather than the symbolic composite masks of the pre-Columbian tradition. And those masked dancers continue the ancient tradition even though they may participate in the most European of ritual forms.

The European forms are varied. Citing Ralph Beals,[58] Gertrude Kurath points out that "influences from Spain were strongest in the sixteenth century due to colonial policies," and these influences brought the folk dramas and dances as well as the mask types then popular in Spain to the indigenous population of New Spain. Chief among these were the Moriscas, Pastorelas, and Diablos.[59] As part of their indoctrination into the new faith, the indigenous population found themselves participating in

imaginary pastorals in which the forces of God triumphed over those of the wicked one; . . . supposedly historical representations in which the Moorish world of the unfaithful fell, beaten by the power of the champions of the faith; dances in which the Christians or the conquerors made the sign of the cross triumph over the Mohammedan Moors or the infidelity of the Indians.[60]

Nothing in all of the syncretic adaptation of Christian forms to indigenous realities is stranger than the fact that even today masked Indians throughout Mesoamerica, and beyond to the north and south, are celebrating in dance the expulsion of the Moors from medieval Spain. The reason for this bizarre result of the syncretic process becomes clear when one remembers that the Conquest of the Americas took place shortly after the Reconquest of Spain in which the Moors were forced back to North Africa. This new conquest seemed an extension of the earlier one to the Spanish as both pitted the spiritual and material force of Christendom against infidels. Throughout Spain, and ultimately throughout Europe, a dance-drama known as Morisma reenacted the triumph of the Reconquest as costumed Spanish Christians engaged and defeated the costumed forces of the Moors.[61] That dance-drama came to the New World as an integral part of the cultural equipment of the invaders and was soon made relevant to the Conquest of the Americas. No doubt performed in the Antilles before the Spanish even reached America, the first recorded performance by Spaniards on this continent occurred in 1529, and the dance-drama was an integral part of Spanish fiestas in New Spain from that time on. Between 1600 and 1650, the dance reached the pinnacle of its importance among the Spanish colonists, but as it waned in importance among them, as they gradually distanced themselves from the customs of the mother country, it paradoxically grew in importance among the mes-

tizo and indigenous populations, although for different reasons.[62]

It had been introduced to the newly converted indigenous population by the missionary priests as a means of indoctrinating them with the Christian view of earthly life as a struggle between good and evil, and while the success of the priests in inculcating that view is debatable, their success in introducing the drama is still evident. By the twentieth century, it had become solely an indigenous institution and was no longer performed even by mestizo groups. In fact, according to Arturo Warman, its presence today can be considered diagnostic of the indigenous nature of the group performing it.[63] As the subject matter does not seem directly relevant to the realities of Mesoamerican Indian life, the reasons for the popularity of the dance are not entirely clear. While "the absolute Catholicism of these dances is an article of faith among the Indians," there are a number of suggestions that the enthusiastic adoption of the Moors and Christians was in some measure a result of its ability to encompass "vestiges of aboriginal ritual."[64] And that ability may come, in turn, from the pagan past of the Spanish dances themselves.

Although Spanish history is the apparent source of the Moriscas, it seems probable that they actually represent religious acculturation in that more ancient pagan dances associated with spring fertility rites and other events received a new lease on life when they were transformed into festivals to celebrate Christian victory over the infidels.[65]

Thus, a level of metaphoric significance may have existed under the Christian veneer of the dance, making it easily assimilated by the tradition of Mesoamerican spiritual thought, which, after all, focused a great deal of attention on that annual moment of rebirth generated by the spiritual force that sustained life.

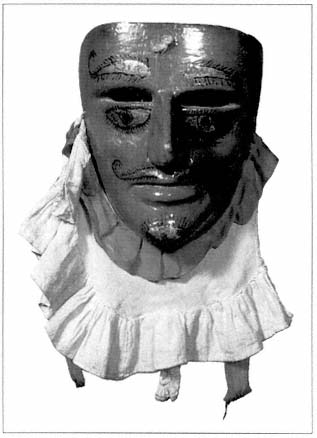

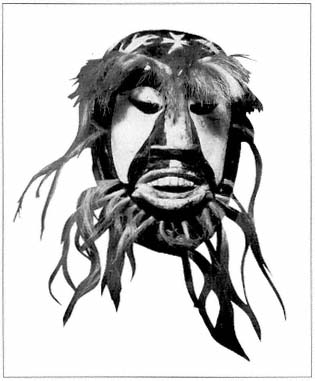

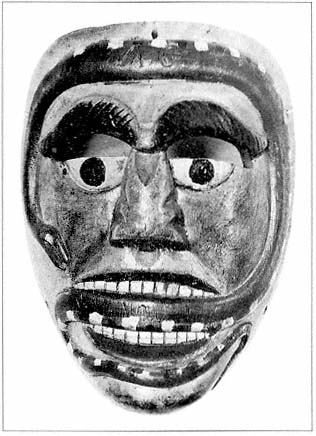

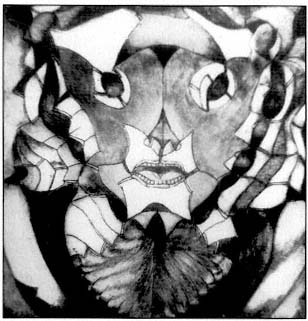

Whatever the reason for its successful implantation in the Americas, that success is undeniable and can perhaps best be measured by the number of variants of the original dance which presently exist,[66] variants that can be divided into two fundamental types. In the first, the struggle enacted by the masked and costumed participants still pits the Moors, often wearing dark masks (pl. 61), against the Christians, either unmasked or wearing light-colored masks, in a combat dance-drama filled with a bizarre mixture of historical references and anachronisms that lends importance and dignity to the mythic struggle being reenacted. A contemporary version performed in Tlaxcala, for example, has Christian characters with such names as Carlomagno, Oliveros, Roldán, Ricarte, and Guy de Borgoña confronting Moors called Almirante Balán, Fierabrás, Mahoma, and Lucafer as well as the devils Apolin and Zapolin.[67] In a variant popular in the Sierra de Puebla, the Christians are led by Santiago (Saint James), the patron of the Spanish forces during the Reconquest of their homeland and the Conquest of the New World, and the Moorish forces are often led by Rey Pilatos (King Pontius Pilate) and count among their soldiers a number of Pilatos. Essentially, the drama opposes the forces of good—Santiago and the Christiansto the forces of evil—Pontius Pilate, Mohammed, various specifically named devils, and the Moors. As we have seen, such an opposition of good and evil, symbolized here by the dark and light masks, is far more characteristically European and Christian than indigenous, so that, superficially at least, it seems clear that in theme as well as content, the dance of the Moors and Christians is a Spanish introduction.[68]

Pl. 61.

Mask of a Moor, Dance of the Moors and Christians, Cuetzalan,

Sierra de Puebla (collection of Peter and Roberta Markman).

This makes the existence of the other fundamental variant of the dance even more difficult to explain, for in it, the Mesoamerican native population, usually identified in the dance as Aztecs, replaces the essentially evil Moors in the struggle with the Christians. Although this variant exists in a number of forms, they are generically known as Dances of the Conquest and exhibit "the core pattern" of the dance of the Moors and Christians.[69] That the Indians could have become involved with the expulsion of the Moors from Spain

seems strange, but it is even stranger that they could have been brought to define themselves as evil and to celebrate their own defeat.[70] The explanation of this phenomena most in accord with the ideas recorded by various ethnographers among the Indians themselves is that from their present position as Christians, they can regard the history of the "defeat" of their forebears as a victory for Christianity, which made possible their present status. Significantly, that interpretation portrays the drama as illustrative of the symbolic process of rebirth identified by Foster, although not in a fertility context.

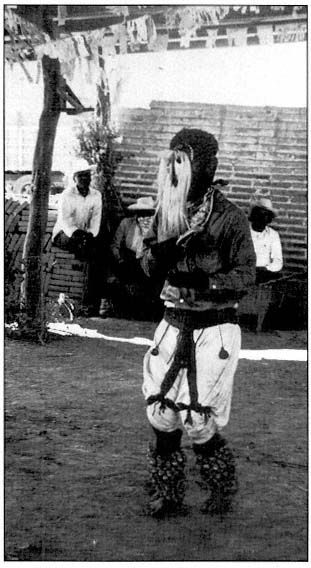

Two variants of the Dance of the Conquest are particularly interesting from our point of view because they illustrate the vitality of the dance today as well as the differences in the processes of syncretism in the two major areas of Mesoamerica. In central Mexico, the Concheros, "a highly organized votive dance society," have as their primary activity the performance of a variant of this dance performed unmasked in fiestas from Taxco to Queretaro to which they make pilgrimages. Organized into "mesas" in military fashion, "they are like a religious army marching to fiestas to make a sacrifice, or an offering, of their dance,"[71] which they perform to the music of the concha, a lutelike instrument fashioned from the armadillo shells from which their name is derived. While the Concheros may accurately be described as "a nativistic complex for men and women of all ages in search of Indian tradition,"[72] it must be remembered that the native tradition, for them, is at least nominally Christian, and the Conquest provided the crucial, God-given opportunity for the conversion of the indigenous religion to Christianity. The Conquest, then, was a victory rather than a defeat.[73]

The case is somewhat different among the Maya, for the process of conversion in the Maya area was even less successful than in central Mexico. The Dance of the Conquest of Guatemala, when contrasted with the activities and beliefs of the Concheros, demonstrates some of those differences. Rather than being performed by a dance cult that makes pilgrimages to various fiestas, the Guatemalan dance is village based, being performed in villages by masked community members (colorplate 10) at the annual festival of the patron saint. While the dance-drama performed by the Concheros focuses its attention on the conversion of the indigenous population and the beneficent results that flowed from it, the Guatemalan dance-drama is seen by the peoples of the villages on one level as a form of historical instruction that emphasizes their glorious indigenous past.[74] On that level, the religious motivation is neither exclusive nor always even paramount but is, as Bode points out, somewhat subordinate to the role of the dancedrama in defining for the people what it is to be Maya.

The Conquista is less than sacred and more than habit. The dancers do not fulfill esoteric vows. Nor do they sustain relatively heavy financial sacrifice, practice long hours, and recite perfectly in a high plaintive voice merely for tradition's sake. They are evoking a proud past and filling otherwise monotonous lives with the excitement and fellowship afforded in preparing for the dance: in practicing, in getting their costumes, in doing their costumbres, in performing for a people eager to have recounted again and again the story of Tecum.[75]

And the story of Tecum is the story of their past glory, now to be experienced through the spectacle of the drama.

According to Tedlock, that drama, as it is performed in Momostenango today, "is strongly biased against the conquerors." The focus is on the three main indigenous characters, each of them identified by characteristic masks: the leaders Rey Quiché, Tecum Umam, and Rey Ajitz who is the red dwarf Tzitzimit.

Rey Quiché is terrified by the Spanish forces; he gladly receives baptism and thereby survives the Conquest. The brave Tecum Umam marches into battle against the Spanish; he refuses baptism and dies. The C'oxol or Tzitzimit correctly divines the defeat; he also refuses baptism, but instead of taking arms, he runs off to the woods to live . . . [where] according to Momostecan accounts, the C'oxol gave birth to Tecum's child. . . . The moral of the drama seems clear. The political leader accepted baptism, the military leader accepted death, and the customs survived the Conquest by going into the woods, where the lightning-striking hatchet of the Tzitzimit continues to awaken the blood of novice diviners and where the child of Tecum still lives.[76]

But there is another level of meaning here. Garrett Cook's research in Momostenango reveals a specifically religious dimension of this nativistic interpretation of the dance-drama. According to his informants, the characters of the dance are seen as Mundos , "anthropomorphic original beings" associated with the sacred earth,[77] or in our terms, manifestations of the world of the spirit existing momentarily for a specific ritual purpose and thus identical in that sense to the gods of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica. For the Quiché of Momostenango, then, the Dance of the Conquest is an integral part of an essentially indigenous ritual life required of them by their gods.

The Quiché are animists for whom the supernatural is immanent, not transcendent. They live in an inherited world which it is their job to maintain. The maintenance of the world and its complex institutions, which were created by the primeros, the founders of civilization, is the primary religious duty .[78]

In "the woods," away from the urban centers dominated by the new society, the Maya continue to live in the old ways, according to the old spiritual vision. Paradoxically, the Dance of the Conquest, introduced to replace that vision with the Christianity of the conquerors, has come to symbolize both the inner strength and the essential meaning of those old ways. Thus, defeat has been turned to victory in a very different way from that imagined by the Concheros of central Mexico. And this "victory" is celebrated in the old way—by masked dancers in a ritual performance.

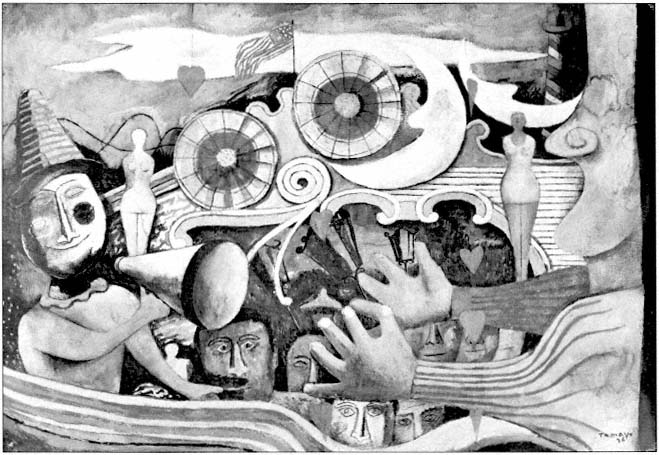

In addition to the dance-dramas based on the struggle between Moors and Christians, the conquerors also introduced folk plays, often featuring masked characters, dramatizing the significant moments of the mythic narrative underlying the new religion. Passion Plays brought Christ's crucifixion to the Indians, while the Pastorelas, outgrowths of medieval European Miracle Plays, depicted Christ's miraculous birth. As Ravicz points out, the Pastorelas, still widely performed in both mestizo and Indian Mexico, were "one of the important ways in which the first missionaries used pre-existing religious patterns" in their proselytizing since in pre-Conquest ritual, "the role of the particular god whose ritual was being celebrated was literally enacted by a chosen member of the celebrants themselves."[79] She refers, of course, to masked impersonators of the gods, indicating the close relationship between pre- and post-Conquest masked ritual.

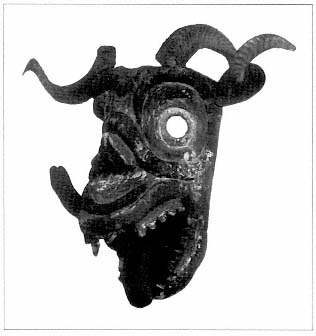

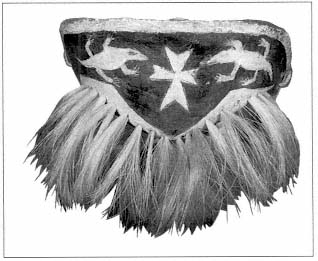

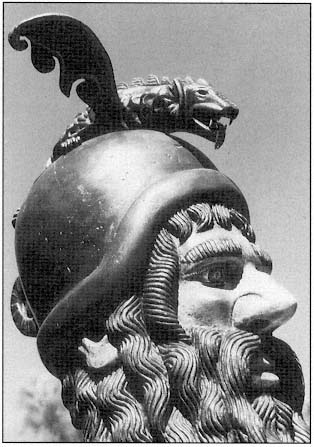

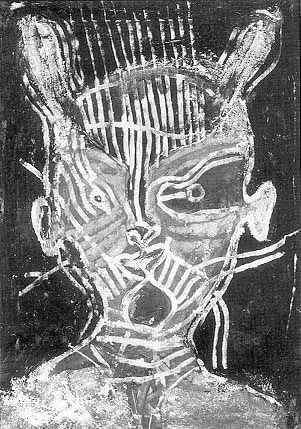

While the thematic centrality of the birth and crucifixion of Christ has obvious relevance to the pre-Columbian connection between sacrifice and rebirth, another motif commonly found in the Pastorelas seems more specifically Christian. That motif involves a struggle between the devils of the play who wear fantastic masks (pl. 62) derived from the European tradition but reminiscent of the composite masks of the pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican past and one or more hermits who, in stark contrast, wear simple, realistic masks (colorplate 11). The struggle may be for the soul of Bartolo, a foolish shepherd,[80] or may arise from the devil's attempt to disrupt the pilgrimage of the shepherds to Bethlehem, but whatever its specific cause, it presents, on a somewhat comic level, a struggle between good and evil. That struggle is also presented on a more serious level as the chief devil, generally Lucifer, attempts to disrupt the ceremonies surrounding the birth of the Christ child. His attempts are ultimately frustrated by the archangel Michael,[81] so that the dramatization of the struggle between good and evil, the struggle the immanent birth of Christ will ultimately resolve, is presented on each of the levels—comic, serious, and symbolic—of the play.

Pl. 62.

Mask of a Devil, Pastorela, Michoacan

(private collection).

In a fascinating way, then, the Pastorelas couple the basic opposition of good and evil, an essentially Christian conception, with the most fundamental image of rebirth in Christian doctrine, the incarnation of Christ—the incarnation of spirit in matter, a conception with obvious and fundamental parallels in indigenous spiritual thought. It is not surprising, then, that of all the dance-dramas introduced by the Spanish, "those celebrating the Nativity are perhaps the most widely distributed."[82] The Christian emphasis on the opposition of good and evil in the context of the opposition of spirit to matter was introduced in part through such plays where the opposition is metaphorically defined by the contrast in masks. But it was understood in terms of the indigenous conception of rebirth, and thus the Pastorelas provide an excellent example of the syncretic process at work. As will be seen in the discussion of the pascola , that particular fusion of Christian and indigenous thought is at the heart of the system of religious thought created by the Yaqui and Mayo of northwest Mexico.

When the missionary friars taught the new religion by encouraging the converted "to honor Christian supernaturals with songs, dances, and folk dramas similar to those in Aztec worship,"[83] they not only allowed but encouraged the Indians to continue to perform, often in masks, what had been one of the most sacred forms of ritual behavior. Now, however, they were to "dance their way into Christendom."[84] By allowing those dances, including even the most indigenous, which were only slightly transformed by Christian themes, to be performed in the church courtyards on Catholic saints' days, the friars encouraged the continuation

of native forms of worship within a Christian context, a practice that is still alive. The results of that encouragement were both predictable and, evidently, apparent even to some of the friars, since in 1555, Indians were specifically forbidden "while dancing, to use banners or ancient masks 'that cause suspicion,' or to sing songs of their ancient rites or histories, unless said songs were first examined by religious persons, or persons who understood the Indian language well."[85]

Thus, the dances and folk dramas and their characteristic masks, along with the other factors we have enumerated (the coincidences between Spanish and indigenous symbols and ritual, the Spanish encouragement to retain some indigenous practices intact and others somewhat modified while "calling them by a better name," the mass conversions of the peasants "often with no more than a token understanding of the new divinities they were to worship,"[86] and the fact that "the confused natives, trying to understand [the Christian concepts], made their own selection of gods, rites, and ceremonies, according to the way these fitted into their version of the world"[87] ) are sufficient to account for Charles Wisdom's conclusion that there appeared to be a

complete fusion [of indigenous and Christian religion] to the extent that the Indians themselves are unaware that any such historical process has taken place. An important point to make is that this has resulted in a new and distinct supernatural system, neither Maya, Mexican, nor Catholic, all the aspects of which are closely integrated to one another and to the remainder of the cultures of which they are a part .[88]

A small but amazingly instructive contemporary example of this fusion of the two traditions is provided by Martha Stone in her discussion of the Conchero dance cult. When she asked a "capitán" to explain the meaning of the twelve rays emanating from the Xuchil, the Conchero's version of the monstrance that in Catholic ritual holds the host, he replied that they symbolized "the twelve rays of the sun, or the twelve disciples of Christ, as you please." And the meaning of the mirror in the center? It represents "the all-seeing powers of Tezcat, a god of our ancestors [Tezcatlipoca was referred to as Smoking Mirror] or the all-seeing powers of the ánimas benditas, as you please."[89] His response carries in potential all the responses of all the practitioners of the folk religion of Mesoamerica, that spiritual structure bearing within its rich symbolism and ritual both of the traditions from which it was formed. Whether in terms of the fiestas and their rituals or the churches and their idols, there are still two cultures at work, and thus one can choose the name that pleases.

Seeing all of this fusion as a "hybrid" religion, Hunt asks,

How is it possible ... that Indians so readily accepted the Christian religion but continued their old rituals, their attachment to ancient symbols, native gods, and autochthonous notions, for over five centuries? The answer is that this is a natural response for a culture with a pantheistic view of the sacredness of the universe. Because reality is one and many, the addition of new images such as the Christian saints or Jesus himself simply expands the repertoire of sacred "words" that can be fitted into the divine "sentence matrix," already defined as simultaneously complex, ultimately unknowable, ever-changing, and unitary .[90]

Her "pantheistic view" is what we have described as the shamanistic foundation of Mesoamerican spiritual thought. The development of syncretism has shown its durability, but it has also demonstrated something more surprising: that foundation was capable of supporting a new, syncretic system of spiritual thought, which can be characterized as the interplay between the indigenous foundation and the materials of the imported religion, an interplay that makes clear that the foundation determines to some extent the shape and appearance of the edifice raised on it. In that sense, it can be said that Mesoamerican spiritual art "still expresses the shamanic state of cosmic unity."[91] More specifically, Robert Redfield observes that the shamanic beliefs and practices that coexist with Christianity in many regions of highland Guatemala are still

essentially pagan. Practically all of these Highland villages maintain . . . shaman-priests who carry on rituals and recite prayers in which pagan deities as well as saints are addressed. These rites are sometimes performed in a Christian church and sometimes at shrines on the hilltops where the pagan gods dwell. Animal sacrifice is practiced; stone idols are still used in connection with religion and magic; not a few of the communities carry on their ritual and even their practical life according to a pagan calendar that has survived from the days before the Conquest.[92]

Mesoamerican Indians generally "view the universe as peopled by spiritual beings; many of the features of nature around them are spiritual and personal."[93] The underlying shamanistic structure of belief remains.

It is clear, then, that Christianity came to Mesoamerica in the form of syncretism rather than as the conversion from one faith to another, which Durán and his fellow missionary priests sought. The Christian forms of spiritual thought and ritual were adapted in terms of what the adapting culture saw as counterparts in their thought and ritual. The two religions became one only in this sense, but since that combination could not resolve the fundamental contradictions between

them, the indigenous structure of spiritual thought remained intact. Even the friars often realized that the two systems were fundamentally incompatible and used that argument as a means of bringing the Indians to accept the new faith and reject their own,[94] but this argument succeeded no better than their other efforts. The Indians, realizing the essential incompatibility of the two, retained the structure of the faith of their forefathers.

Fundamental to that spiritual vision was the idea that the creative force of the spirit entered the world of man through a process of "unfolding" whereby a continuum was constructed which ultimately connected that force to man. Moreover, indigenous spiritual belief saw all things as part of one essentially spiritual reality in which "the microcosm and the macrocosm are but different forms in which one and only one vital order is manifested."[95] Christianity could provide no parallel to this conception as it saw man and this world as "fallen, " as essentially separate from god and the world of the spirit. For the conquering Christians, the world of man and man's physical being were essentially material and could be dealt with by material means; man's spirit was separate from this world and from his body. For the indigenous population of Mesoamerica, no such separation was possible; everything was essentially spirit. Christianity, moreover, proposed that good might ultimately exist without evil, pleasure without pain, and light without darkness, while indigenous spiritual thought, on the contrary, was dualistic in the sense that it conceived of unity as the joining of opposed qualities and was always aware of the simultaneous existence of both halves of those pairs of opposites. For this reason, it was not just difficult but almost impossible for Mesoamerican thinkers to comprehend the idea of a single, monolithic truth.

As we have seen, the result of the intersection of these two mythic systems is extremely complex, but it is perhaps fair to say that while the Conquest destroyed the theoretical superstructure of pre-Columbian religion (i.e., the philosophical and theological speculation of the priesthood), the myths and rituals and the underlying structure to which they gave essential form remained fixed in the minds and lives of the peasants. It was there that the formal and temporal order of the ritual life of the European conquerors merged into the indigenous structure, preserving intact the foundation of pre-Hispanic spiritual thought. The old religion was forced underground, but it remained alive in "a different intellectual context" from that of its earlier splendor.[96] As James Greenberg discovered, what survived was not merely the "bare bones" of that ancient body of belief. "It was only after extensive work that I realized that what I had perceived as 'bones' were the flesh and blood of Chatino belief and that 'Catholicism' had been completely reworked and resynthesized in terms of the pre-existing nexus of ritual and doctrine."[97]

Even as we write, the conflict continues. Today's Los Angeles Times , delivered to our doorstep this morning contains an article headlined: "400-Year Church Ties Cut by Ancient Mexican Tribe." The article recounts "the troubles between the Catholic Church and the Chamulas. . . . Chamula leaders charged that the Catholic bishop in San Cristobal connived to end traditional Mayan forms of worship." In response, they ousted the Catholic clergy from their churches and "called in a preacher from a solitary Christian sect in the faraway state capital" who would not "interfere with the ancient ceremonies."[98]

The vitality of indigenous religion, as exemplified by the Chamulas, corroborates Charles Gibson's answer to his question which we posed earlier: "What, finally, did the church accomplish?"

On the surface it achieved a radical transition from pagan to Christian life. Beneath the surface, in the private lives and covert attitudes and inner convictions of Indians, it touched, but did not remold native habits. Modern Indian society . . . abundantly and consistently demonstrates a pervasive supernaturalism of pagan origin, often in syncretic compromise with Christian doctrine. Although it cannot really be demonstrated, it may be assumed that the pagan components of modern Indian religions have survived in an unbroken tradition to the present day .[99]

Today, while many scholars predict the death of pagan beliefs and customs, the Concheros continue to dance and to pray, "May our ancient religion endure, as it has from the beginning, to the end of all things."[100] Their prayer is repeated—in a variety of words and ritual actions—by indigenous groups throughout Mesoamerica.

12

The Pre-Columbian Survivals

The Masks of the Tigre

O jaguar, most noble, slyest of all the beasts of ancient Mesoamerica, deified for thousands of years by the Olmecs and Zapotecs, by the peoples of Teotihuacán, Tula, and Mexico-Tenochtitlán: fight on wildly in the fray; die on a thousand times in our village fiestas.[1]

The jaguar—as a symbol of the earth, rain, and fertility—did not die with the Conquest but ironically continues to die every year in the festivals in and through which the indigenous folk religion of Mesoamerica exists. This annual death is, as it always has been, representative of the death that precedes rebirth in the eternal cycle of life and death. Thus, the jaguar mask central to the widespread Danza del Tigre in its many variations (to which Fernando Horcasitas refers) provides the best example of the survival of the mask and its underlying assumptions in indigenous ritual. What Gibson says of pre-Columbian survivals generally—that while a continuity of existence from pre-Columbian times is difficult to demonstrate, "it may be assumed that the pagan components of modern Indian religions have survived in an unbroken tradition to the present day"[2] —is specifically true of today's jaguar mask and its accompanying ritual; without exception, scholars accept Horcasitas's contention that "from all indications, la Danza del Tigre has pre-Hispanic roots."[3]

The earliest evidence we have for the existence of the mask and the dance, while colonial, strongly suggests their pre-Columbian origin. In 1631, the Inquisition prohibited the Danza del Tigre in Tamulte, Tabasco, since "it contained hidden idolatry offensive to our Religion." Specifically, dancers "disguised as tigres " fought, captured, and simulated the sacrifice of a dancer dressed as a warrior in "a cave called Cantepec"; the simulated sacrifice was followed by an actual sacrifice of hens.[4] On the basis of this and other evidence, Carlos Navarrete concludes that "popular 'animal dances' [often] concealed ancient pagan rites."[5] That those rites in this case are involved with the provision of water from the world of the spirit is demonstrated by the ritual's familiar combination of thematic motifs. The union of blood sacrifice, the cave, and a human being disguised as a jaguar (tigre , in the context of indigenous ritual, means, and is generally translated as, jaguar) in this ritual configuration recalls the pre-Columbian rain gods and their ritual propitiation at the time of the coming of the rains. The central position of the jaguar mask makes the connection clear; and that colonial mask was the forerunner of the numerous jaguar masks worn today, 350 years later, masks which are visually reminiscent of their pre-Columbian predecessors.

The modern mask, in most of its variations, generally displays the features of the pre-Columbian, jaguar-derived rain god masks—prominent fangs, a pug nose, round eyes with prominent eyebrows, and often a large, though not bifid, tongue dangling from its mouth. In many cases, the wearer looks out of the mask through the open mouth,[6] an unusual arrangement in modern masks but one reminiscent of pre-Columbian practice. Thus, both the earliest evidence of tigre mask ritual and the appearance of the masks themselves suggest a pre-Columbian origin.

Probably the most widespread and surely the best-documented ritual dance-drama is the Danza de los Tecuanes found primarily in the central Mexican states of Guerrero and Morelos.[7] It recounts "the hunting and killing of a tecuani or jaguar" who has devastated the local village. The version detailed by Horcasitas in 1979 begins with the wealthy landowner, Salvadortzin, and his assistant recruiting hunters, among them an archer, a tracker, and Juan Tirador, the marksman who will

finally shoot the jaguar. Once they are recruited, Salvadortzin gives them their charge:

Viejo Rastrero! Old Tracker! I want you to hunt and kill the tiger because the tiger's been doing a lot of damage. The tiger's ruined seven villages, the tiger's destroyed seven hamlets, the tiger's finished off all the good cows, the tiger's eaten up all the good donkeys, the tiger's eaten up all the good bulls, it's eaten up all the good goats, it's eaten up all the good sheep. It's even devoured all the good girls who go to the well for water, man! I'll pay you well to go get the tiger, man![8]

In a similar speech delivered by Don Salvador to his mayordomo in the version of Texcaltitlán in the state of Mexico, the landowner says the tigre is consuming the yearling bulls, the calves, the lambs, the kids, the piglets, and the rabbits, to which the mayordomo responds, "We are going to die of hunger."[9] Thus, the wild animal, the jaguar, is destroying the domesticated animals that support human culture by providing food in an orderly and regular manner and is serving here the same structural function it had in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica from the time of the Olmecs; it is still generally symbolic of the untamed forces of nature that must be brought into harmony with the order underlying human society.

And it is through the accoutrements of human society that that order is achieved. Salvadortzin questions Juan Tirador, who will kill the jaguar, about his looks and then about his weapons:

"Juan Tirador, they tell me that you are brave. They tell me you are a good hunter. Is it true that you have a strong heart? Is it true that you have a big mustache? Is it true that you have a bushy beard? Is it true that you are handsome and have rosy cheeks?" All this is in reference to Juan's wooden mask. To each of these questions he answers "Yes, yes. True, true." "Is it true you have good weapons?" Juan Tirador then describes his hunting equipment, which is that of a small army: traps, cords, pistols, shotguns, munitions, rifles, muskets, bullets, cartridges, machetes, knives, daggers and so forth.[10]

The answers seem deliberately designed to point up the difference between the "natural" mask and claws of the jaguar and the "civilized" mask and weapons of the hunter and thus reiterate the opposition of nature to culture suggested by the destruction of the domesticated animals by the wild jaguar. And this theme is found in other details of the dance-drama. Much is made, for example, of the wealth of the landowner and the paying of Juan Tirador, a motif emphasizing the social structure in opposition to the natural behavior of the jaguar: the hunter kills as a profession, the jaguar as an expression of his being. The emphasis on the dogs used by the tracker suggests the theme of domestication in another way: domesticated animals can be used to subdue wild animals as well as be destroyed by them. And the final skinning of the jaguar to make various items of clothing for the hunters and the dogs demonstrates that nature is not only potentially destructive but can also be useful to human society when brought under control. It is fair to say that the drama turns on the underlying opposition between nature and culture and in the killing of the jaguar, illustrates the necessity of "domesticating" wild nature.

The final speech of the variant enacted at Tlamacazapa, Guerrero is fascinating in this regard:

"But wait, Juan Tirador," shouts the Governor. "The jaguar is so big that I will give you a piece of skin for your coat, for your vest, for your belt, for your shirt, for your pants, for your leather jacket, for your chaps, for your trousers, for your leggings, for the case for your weapons. Even for the shoes of your puppies! Even for your mask, man!"[11]

The dead jaguar (a human being wearing a mask) thus becomes a mask for the hunter in a startling switch ending the dance and making clear both the sophistication of this tradition of mask use and the awareness within the drama of the metaphoric nature of the mask, for the shoes for the puppies and the mask, the last of the items enumerated, are the only items not part of everyday life outside the drama; what was formerly wild can be used to support culture and in that use becomes a "mask" to cover the inherent "wildness" of all life. That this theme should exist in a dance-drama whose central character wears the mask of a tigre, or jaguar, indicates clearly that the symbolic merging of man and jaguar in the were-jaguar masks of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica continues, albeit in altered form, and that the were-jaguar still stands as a metaphor for the sustenance of man by the world of the spirit through the fertility of nature.

While the dance-drama of los Tecuanes lacks most of the earth and fertility symbolism associated with that pre-Columbian were-jaguar, a closely related variant in which essentially similar masks are employed retains that symbolism, as its name, los Tlacololeros , suggests. The name is derived from tlacolotl , Nahuatl for a plot of land,[12] and the dance "dramatizes the efforts of men to cultivate their fields and their struggle against the tiger that ambushes them and threatens to destroy their human labor."[13] The two dance-dramas seem to have divided the two forms of domestication characteristic of agricultural life—that of animals and the land—into two separate, but clearly related, dances that coexist in the state of Guerrero; perhaps the single colonial source of these modern variants[14] united the two forms of domestication.

While los Tecuanes is almost wholly involved with animals, los Tlacololeros deals with the agricultural cycle. As the drama begins, the jaguar

taunts the spectators while the ten or twelve tlacololeros, all similarly dressed and masked and each named after a particular plant, prepare a plot of land and plant a seed, after which they complain to the chief of the hunters of the jaguar who threatens their agricultural efforts. In response to these complaints, the chief uses a dog, la Perra Maravilla , to track the jaguar, and when he is brought to bay, often in a tree, the chief finally kills him. After the hunt, as in los Tecuanes, there is a good deal of discussion of the size of the jaguar. The tlacololeros then burn the plot of land in preparation for the next planting. While the land is burning, pairs of dancers whip each other, often violently, on their padded costumes, the sounds of the whips simulating the sound of the fire. Often a clownlike character carries a dessicated squirrel with which he torments the other characters and the audience.[15] Thus, all the elements of the cycle of life, especially as it applies to agriculture, are here, and the theme of life coming from death with its complementary notion of the necessity of the sacrifice of life is clearly evident. Often, though not always, los Talcololeros is presented as a part of rain-petitioning ceremonies,[16] providing yet another link to the agricultural cycle and to the were-jaguar mask of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.

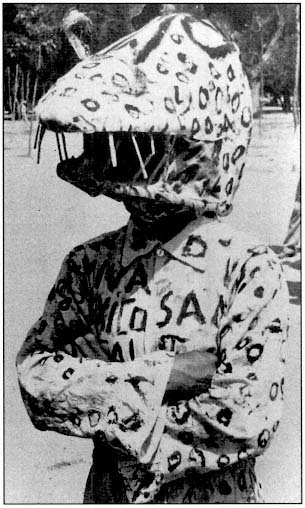

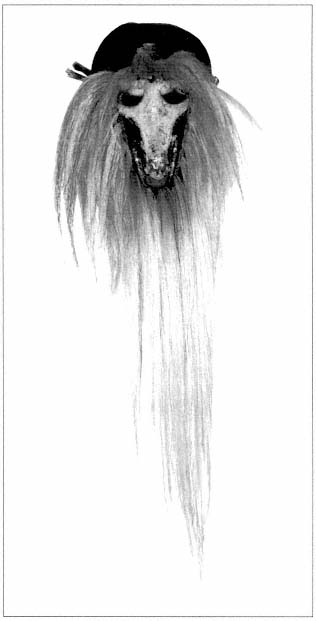

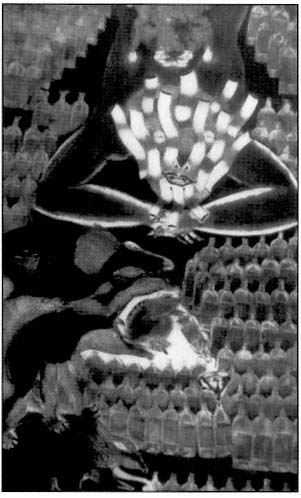

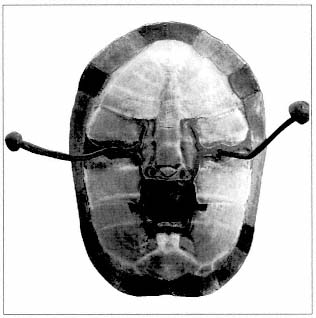

Pl. 63.

Mask of a Tigre, Guerrero. The wearer of the mask

may be seen through the mask's mouth.

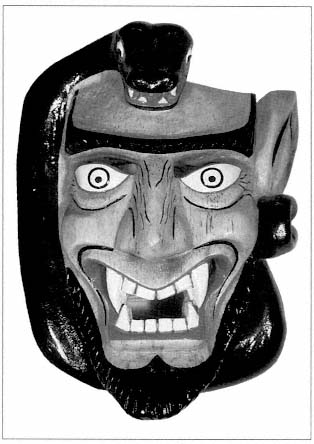

Pl. 64.

Masked Tigre, Dance of the Tecuanes, Texcaltitlán,

State of Mexico (reproduced with the permission of FONADAN).

The tigre masks employed in the dances of Guerrero and Morelos range from carved and lacquered wood masks (pl. 63), often magnificent creations, to mask helmets made by covering a reed or wire frame with painted cloth (pl. 64).[17] Different as the masks are, however, their common origin can be seen in their remarkably similar, though differently interpreted, features. Always, for obvious reasons, the mouth is the focus of attention. Large and generally fanged, it often has a protruding tongue and sometimes provides the opening through which the wearer sees. In such cases, the face of the wearer can be seen within the mask exactly as the opossum mask helmet from Monte Albán (pl. 34) symbolically revealed its wearer within. The nose of the tigre mask is generally a feline pug nose, and the eyes are often distinctly circular and goggle shaped, though not always. The masks generally bristle with clumps of hair, eyebrows, and mustaches of hog or boar hair and are usually painted yellow with black spots. The masks comprised of these features range from relatively realistic portrayals of the jaguar to highly stylized ones, but they all emphasize at least some of the features we have seen in the jaguar-derived pre-Columbian rain gods from the Olmec were-jaguar[18] to the Oaxacan Cocijo, the Tlaloc of central Mexico, and the Maya Chac.

Although there is some regional variation, masks essentially similar to these represent the jaguar in ritual throughout Mesoamerica, and other elements of los Tecuanes and los Tlacololeros consistently appear along with the familiar mask.

First, the tigre seems always to be accompanied by boisterous, generally sexually based humor. At times, the jaguar interacts with the spectators, teasing and taunting them; at times, the performance includes a ritual clown, often carrying a stuffed animal, who engages in sexual foolery; and at other times, the various characters within the drama involve themselves in similar antics. Whatever form it takes, however, there is always humor. As Horcasitas puts it, "The dance is a comedy, yet it would show disrespect to omit it from the village fiesta. It is holy and funny. Religious feeling here is expressed in merriment, not in gloom."[19] That the dances are thought of as religious is indicated by their being preceded and concluded by specifically religious ritual and by their often being presented in the courtyard of the church. But the generally sexual nature of the humor is obviously related to the fertility theme of the ritual drama and is remarkably compatible with its basic nature/culture opposition as it suggests that human sexual proclivities must be controlled for culture to exist. In this connection, it is significant that male participants are generally required to observe a period of sexual abstinence that provides the opposite extreme from the wild sexuality of the humorous elements of the drama. The message is clear: normal human life within a culture is characterized by what the culture defines as normal sexual activity—neither the abstinence of the ritualist nor the wild abandon of the tigre and other characters.

Along with the humor that functions in the context of the nature-versus-culture oppositions, the tigre performances of modern Mesoamerica almost always involve a series of up/down oppositions. In the version just described, the jaguar climbs a tree where he is finally killed. Other versions are more spectacular; in a variant performed at Texcaltitlán, Guerrero, for example, the jaguar first climbs a tree in an attempt to escape the hunters and then climbs a rope extending from that tree to the top of the nearby church tower.[20] Conversely, the tigre is often involved with caves. These up/ down and in/out oppositions seem clearly related to pre-Columbian pyramid/mountain and temple/ cave ritual and assumptions, especially since the summits of mountains and the inner reaches of caves, as we have seen, were intimately associated in myth and ritual with the provision of rain by the gods. Significantly, the tigres are often involved with church towers, that is, contemporary, religiously defined "summits."

The tigre dances also share a fundamental involvement with violence. The central character, the jaguar, is violent in his destruction of other characters and is finally disposed of violently, and dramatic violence often occurs between the other characters. Moreover, the violence within the drama often provokes very real violence among the spectators. Because of the large amounts of alcohol consumed by festival participants and the emotions aroused by the dance-drama, real blood is often shed and, not infrequently, participants are killed. But this is expected and, in a strange way, seen as desirable. Véronique Flanet, in discussing the festivals in the Mixteca, says that a fiesta is not deemed successful if no one has been killed. She quotes typical remarks: "Last year's festival was much better; there were seven people killed," or "When no one is killed, there is nothing worth mentioning about a fiesta."[21] This emphasis on, and expectation of, bloodshed and violent death—both within the ritual performances and without—may seem barbaric to us and to the civil and ecclesiastical authorities of modern Mexico, but as an integral part of the ritual fertility festivities, it reflects the fundamental connection in the Mesoamerican mind between sacrifice and fertility. Seen in this way, it is in perfect accord with other modern practices and assumptions with the same pre-Columbian roots. One thinks, for example, of the penitentes throughout Mesoamerica and the bloody depictions of Christ in indigenous art.