Destruction of Riparian Systems Due to Water Development in the Mono Lake Watershed[1]

Scott Stine, David Gaines, and Peter Vorster[2]

Abstract.—During the early decades of this century over 320 ha. (800 ac.) of marsh, wet meadow, and riparian woodland covered the Grant and Waugh Lake depressions and lined the banks of lower Rush, Parker, Walker, and Lee Vining Creeks. Construction of reservoirs and diversion of streams have destroyed virtually all of this wetland vegetation. Streamside riparian systems could be restored by allowing moderate amounts of water to flow down the creeks.

Introduction

Prior to the large-scale manipulation of streamflow in the Mono Basin, the lower reaches of Parker, Walker, Rush, and Lee Vining Creeks were bordered by riparian woodland, wet meadow, and marsh vegetation. The depressions now occupied by Waugh Lake and Grant Lake Reservoir supported extensive stands of marsh and wet meadow. This paper briefly describes the former extent of this wetland vegetation, and documents its destruction due to water impoundment and diversion.

Flow Regime Under Natural Conditions

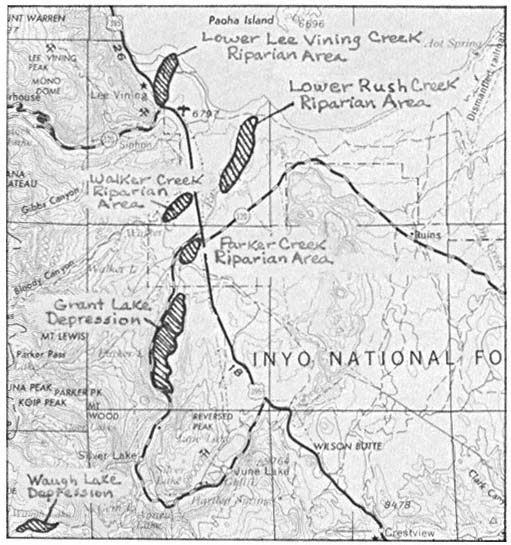

Rush, Parker, Walker, and Lee Vining Creeks head at the 3,200- to 3,960-m. (10,500- to 13,000-ft.) crest of the Sierra Nevada east of Yosemite National Park (fig. 1). The streams debouch from their bedrock canyons on the east side of the Sierra at elevations ranging from 2,130 to 2,440 m. (7,000 to 8,000 ft.), then flow 11 to 16 km. (7 to 10 mi.) across alluvial, lacustrine, and aeolian sediments on the floor of the Mono Basin to the shores of Mono Lake.

These streams, which under natural conditions account for approximately 75% of the surface inflow to Mono Lake, are fed primarily by snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada. Peak flows are usually attained in May, June, and July. By September of the average year, flows in the bedrock reaches of the streams have declined significantly. Along the basin floor, however, groundwater from the loose, unconsolidated sediments continues to feed the creeks.

The streams themselves constitute the main source of this groundwater. As they cross their alluvial fans and piedmont slopes, a substantial amount of flow percolates through the coarse sediments. The water is then slowly returned to the streams in their lower reaches. Streamflow in these basin reaches thus remains substantial during the dry months of late summer and fall. Even during prolonged (5- to 10-year) periods of drought, groundwater keeps the lower creek reaches flowing.

Riparian Systems Prior to Water Development

It was along these perennially flowing, lower reaches of Rush, Walker, Parker, and Lee Vining Creeks and in the Grant and Waugh Lake depressions that the most luxuriant wetland vegetation in the Mono Basin was found (fig. 2). Dense groves of aspen (Populustremuloides ), black cottonwood (P . trichocarpa ), willow (Salixexigua , S . lutea , and probably others), Jeffrey pine (Pinusjeffreyi ), and probably mountain alder (Alnus tenuifolia ), interspersed with meadows and cattail marshes, formed riparian corridors that followed the streams practically to the shores of Mono Lake (fig. 3 and 4). Over 243 ha. (600 ac.) of this wetland mosaic laced 13 to 16 km. (8 to 10 mi.) of the river course. Early maps indicate that the Grant and Waugh Lake depressions supported 200 ha. (500 ac.) or more of wet meadow and marshland.

These riparian systems had considerable esthetic, recreational, and wildlife values.

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] Scott Stine is a Graduate Student and Lecturer in the Department of Geography, University of California, Berkeley. David Gaines is an Independent Researcher and Author (P.O. Box 29, Lee Vining, Calif. 93541). Peter Vorster is a Consulting Hydrologist with Philip Williams and Associates, San Francisco, Calif.

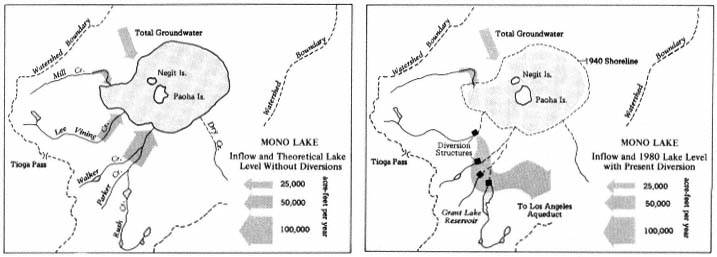

Figure 1.

Index map of Mono Lake (ca. 1953).

John Muir wrote glowingly of lower Rush Creek in 1894 (Muir 1894). In 1924 Joseph Grinnell pointed out the importance of the basin's cattail marshes to birds such as the Least Bittern (Grinnell and Storer 1924). The alluvial reaches of Rush Creek are said to have supported the finest brown trout fishery in the eastern Sierra.[3] And until recently the riparian areas were used extensively by picnickers, hikers, and duck hunters.[4]

Figure 2.

A portion of the USDI Geological Survey Mariposa

1:250,000 sheet (1957) showing major riparian areas.

Water Development in the Mono Basin

While small-scale stream diversions for irrigation, mining, and milling occurred in the Mono Basin as early as the 1850's, it was not until the early years of the twentieth century that water development escalated to significantly impact the region's riparian vegetation. Around 1915 a dam was constructed by the Cain Irrigation District to impound water in the Grant Lake depression. This small reservoir was enlarged in 1926. The Waugh Lake depression underwent similar modification in 1925 when the Southern Sierra Power Company built a small dam across upper Rush Creek.

In 1930 Los Angeles voters approved a $38-million bond issue to finance the extension of the City's aqueduct northward from the Owens Valley into the Mono Basin. By 1934 Los Angeles

[3] Johnson, Wes. 1981. Personal communication.

[4] Mathieu, Lily. 1981. Personal communication.

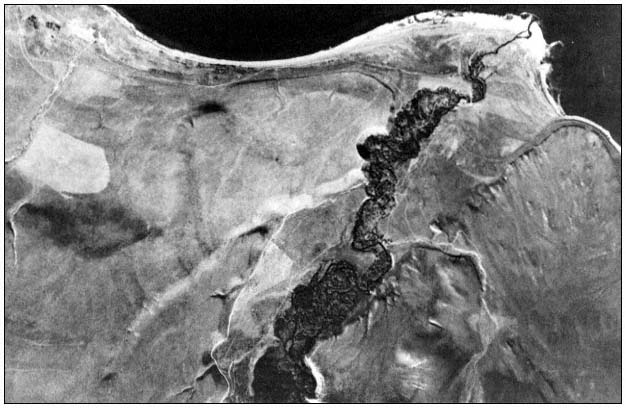

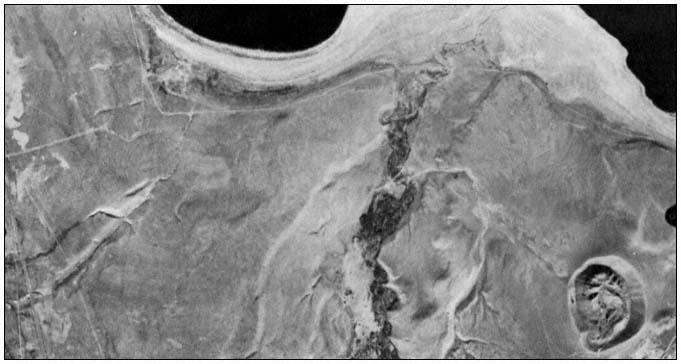

Figure 3.

1930 aerial photograph of lower Rush Creek, Mono Lake at top. This

was the most extensive area of riparian vegetation in the Mono Basin.

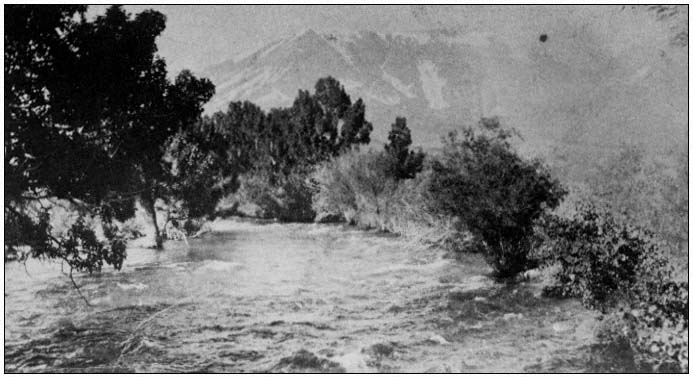

Figure 4.

Rush Creek about 0.16 km. (0.1 mi.) southwest of Highway 395, ca. 1920. (Courtesy of Enid Larson.)

had consolidated its rights to the basin's principal streams. Six years later workers completed a network of pipelines and impoundments; this included the further enlargement of Grant Lake Reservoir. The following year, in 1941, the first diversions of water from Mono Basin began (Gaines 1981).

During the next 30 years an average of 55,000 acre-feet (AF) of Mono Basin water per year was turned southward. An average of 40,000 AF per year, however, continued to flow down the creeks on an irregular basis (Los Angeles Department of Water and Power 1974).

In 1970, with the completion of a second Owens Valley aqueduct, the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power (LADWP) substantially increased its take of Mono Basin water (ibid .; Gaines 1981). During the past decade nearly the entire flows of Rush, Parker, Walker, and Lee Vining Creeks have been diverted southward. Effective groundwater replenishment has ceased. Except for brief periods in 1978 and 1980 the streams have remained essentially dry below the diversion dams (fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Map of Mono Lake showing the major tributary streams and points of diversion. Since diversions began in 1941

the lower stretches of Rush, Parker, Walker, and Lee Vining Creeks have been transformed from perennial streams

into abandoned washes. Mono Lake has fallen 13.7 vertical meters (45 vertical feet), its volume has been halved,

its salinity has doubled, and Negit Island has become connected to the mainland.

Impact of Water Diversions on Riparian Systems

The early impoundment of water behind the Grant and Waugh Lake dams led to the immediate loss of some 140 ha. (350 ac.) of riparian system. Later enlargement of the Grant Lake reservoir by the LADWP flooded an additional 61 ha. (150 ac.) of marshland and meadow.

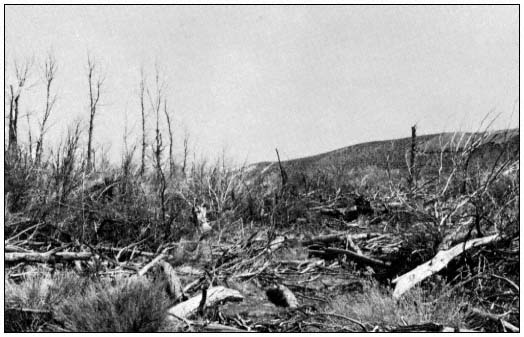

The destruction of streamside wetlands occurred more gradually. By the early 1950's the riparian vegetation along Lee Vining Creek was so desiccated that fire was able to consume some 40 ha. (100 ac.) of woodland.[5] During the early 1970's the arboreal vegetation along the lower creek reaches is said to have been brown and withered.[6] Photographs from 1978 show that little live vegetaton remained along the once-extensive Rush Creek wetlands (fig. 6 and 7).

Today the marshes and wet meadows that once lined the basin stretches of the streams have vanished entirely. Most of the deciduous trees have died (fig. 8). The few Jeffrey pines that remain are not establishing seedlings. Streambanks that were once clothed with mesic vegetation have been colonized by Great Basin xerophytes such as sagebrush (Artemisiatridentata ) and rabbitbrush (Chrysothamnusnauseosus ).

[5] Banta, Don 1981. Personal communication.

[6] Mathieu, Lily 1981. Personal communication.

Figure 6.

1978 aerial photograph of lower Rush Creek. Virtually no live riparian vegetation remains.

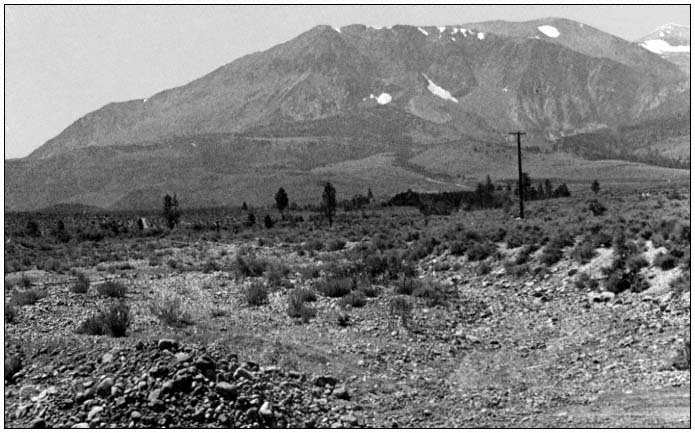

Figure 7.

The abandoned channel of lower Rush Creek in 1981. This photo was taken from the same point as figure 4.

Figure 8.

All that remains of the once-extensive riparian woodland along lower Rush Creek.

Restoration Potential

Restoration of riparian vegetation along lower Rush, Parker, Walker, and Lee Vining Creeks would require a reduction in present diversions and maintenance of minimum streamflows throughout the year. Under these conditions it is thought that riparian vegetation would reestablish itself relatively rapidly.

The prospects for curtailing water diversions hinge on the outcome of current efforts to stabilize the level of Mono Lake. This unusual body of chloro-carbonate-sulfate water is shrinking and increasing in salinity due to the diversions, endangering a unique ecosystem and hundreds of thousands of nesting and migrating birds. Environmentalists and residents are attempting to preserve Mono Lake through legislation and litigation. They are opposed by the LADWP, which argues that diversions are critical to the City (Los Angeles Department of Water and Power 1974, Gaines 1981).

In December, 1979, an Interagency Task Force on Mono Lake, chaired by the California Department of Water Resources and consisting of representatives from Federal, State, and local agencies, recommended that Los Angeles reduce its diversions from the Mono Basin from an average of 100,000 AF to an average of 15,000 AF per year. The Task Force documented how the City could replace this water through an expanded program of conservation and waste-water reclamation (California Department of Water Resources 1979). Implementation of the Task Force Plan would also restore riparian vegetation along lower Rush and Lee Vining Creeks. To date, however, the opposi-of the LADWP has blocked the Task Force Plan and prevented any reduction in diversions (Gaines 1981).

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Adreinne Morgan and Sharon Johnson for cartographic assistance, and to Mono Basin residents Don Banta, Lily Mathieu, and Wes Johnson for historical information.

Literature Cited

California Department of Water Resources, Southern District. 1979. Report of the Interagency Task Force on Mono Lake. 140 p.

Gaines, David. 1981. Mono Lake guidebook. 113 p. Mono Lake Committee-Kutsavi Books, Lee Vining, Calif.

Grinnell, Joseph and Tracy I. Storer. 1924. Animal life in Yosemite. University of California Press, Berkeley, Calif.

Los Angeles Department of Water and Power. 1974. Los Angeles water rights in the Mono Basin and the impact of the Department's operations on Mono Lake.

Muir, John. 1894. The mountains of California. 381 p. T. Fisher Unwin, London.