Valuables

In common with many other New Guinea societies the Maring class a range of goods in a named category, munggoi . The term has two meanings. In a general sense it refers to any object that is described in Tok Pisin as samting pulim pe , something that "pulls pay" or has exchange value. In this sense it may refer to any good passed in trade or major and minor prestations. In a more restricted or focused sense it is confined to "valuables" or "prestige goods." Paradigmatically, valuables in this narrow sense embrace items passed in major prestations: pigs, cassowaries, certain shells, stone and now steel tools, and paper money. Some high-value bird plumes and marsupial skins are also classed as munggoi in this restricted sense, although they are not used in major prestations among the western Maring. The Kundagai explain that they are "valuables" because they are of comparable exchange value to pigs, the preeminent object of ceremonial exchanges. Indeed, many such plumes and skins are used to acquire by trade pigs later killed for prestations. In all, some thirty-six objects fall into the category of "valuables" (although some informants are inclined to expand the list). Only twelve of these, however, are valuables in the restricted sense and are or were regularly employed in major ceremonial exchanges, and only munggoi are so used. Although traditionally the western Maring, including the Kundagai, did not use plumes in major prestations, the eastern Maring and the Narak and Kandawo have always done so. The Kundagai, however, have recently received some Red Bird of Paradise, Hornbill, and Paradise Kingfisher feathers in bridewealth, mainly from eastern Maring communities, although they do not include feathers in any major prestations they make.

The category munggoi as valuables includes items that may also be used as decorations, mokiang , but not all mokiang are also valuables. Many non-munggoi decorations are also traded, though less commonly

than are munggoi and generally at lower exchange rates. There is no doubt that the introduction of money has facilitated trade in these lesser goods and that, although some of these goods were formerly obtained by the Kundagai from beyond their territory, this was mainly in minor prestations from kinsmen rather than by trade. A few items are neither munggoi nor mokiang and are occasionally exchanged for money; these, however, were probably seldom if ever traded in the past.

Appendix 3 gives details of over seventy goods transferred in trade. The catalogue of items actually traded in any one period of time has varied as indicated in the appendix. Most things no longer traded are not used for any other purpose, such as decorations, or even retained as mementos of the past. For instance, to my knowledge no Kundagai now owns a dog-tooth necklace or pack of native salt.

Over one hundred items, animal, vegetable, and mineral, provide decorations, but I recorded only forty-seven used in trade. Of the fifty-three species of birds used in decorations, twenty-seven are or have been traded.

Goods passed in trade can be classed broadly either as more or less ubiquitous or as specialized and localized in origin. Here I classify goods relative to their availability in Tsuwenkai. Items found in both Tsuwenkai and many other areas of dissimilar environment are not of specialized origin. Things found only in Tsuwenkai or a limited number of other similar environments, or widely distributed goods absent from Tsuwenkai, are classed as being of specialized origins. By this reckoning twenty-three, or somewhat less than half of the items ever traded, are the products of ecologically or technologically distinct areas. In most cases items are peculiar to high or low altitudes, although salt, stone, and some pigments are derived from localized deposits that are distributed with little relation to altitude.

The Maring grade valuables into broad hierarchic categories of order of value. Unlike, for instance, the Mae Enga (Meggitt 1971: 200), the Maring hierarchy does not involve rigid restrictions on the interconvertibility of items of different hierarchic levels. The Kundagai say that ideally items of one level can be exchanged for those in any other level. Mae Enga valuables normatively can be exchanged only with items of the same or immediately adjacent levels. Nonetheless, on the one hand, exchanges of goods with widely divergent value would not be contemplated by the Maring. On the other hand, convertibility. between Maring levels is enhanced insofar as items within any one level

are not of equal exchange value. The levels of value therefore do not conform to a scale of exchange value but are, rather, a hierarchy of "worth or desirability" (Meggitt 1971: 199).

Scales of value have altered over time as items available for use in prestations have changed. Table 13 lists hierarchies of valuables around the year 1900 (as related by an old man born around that time) and in the present. Opinion varies somewhat as to the number of levels and the allocation of specific items in the contemporary hierarchy.

Some informants list money in the same category as pigs, shells, and steel tools, because, like those items, it is a major component of prestations. Those who place money in a separate category of superior value do so because they say that since money can be converted to any other item more freely than other valuables it is the most valuable. It is therefore the most desirable of all goods.

Other categories crosscut these hierarchies: all shells are glossed mengr , bird plumes as kabang an (feathers) or kabang wak (skins), and marsupial fur as koi-ma an and skins as koi-ma wak .

Ethnographers frequently record quantities of valuables transferred in ceremonial exchanges. Except for pigs, however, there are few published details available on valuables stocks retained by individuals. A major aim of the following discussion is thus to document patterns of ownership of valuables among the Kundagai and show how the means of acquiring valuables varies. It must be conceded immediately that custodianship of valuables does not necessarily mean ownership, as one may hold temporary stewardship over, say, shells that belong to others. Nonetheless, the great bulk of valuables I saw during a census of valuables collections were identified by their custodians as their personal property.

I did not discern any reluctance on the part of the Kundagai to show me their plume and shell collections. It is possible that some men had stored separately shells that they had received in, or were about to give in, prestations, and that they preferred to keep the fact secret from my assistants and spectators in case their display should provoke claims or comments. In the absence of signs of evasiveness, however, I am confident that I saw most shells and plumes owned by resident Kundagai. I also saw some valuables belonging to absentees which were stored with resident kinsmen. In their general willingness to display and discuss valuables collections the Kundagai dearly contrast with some other societies—such as the Mae Enga, at least in respect of pigs (Meggitt 1974)—where such information is sensitive and secret.

TABLE 13. | ||||

Order of Value | Items | |||

A. ABOUT 1900 | ||||

1. | Greensnail shells | |||

2. | Pigs, live cassowaries, plumes of Astrapia, Sicklebill, Superb and Saxony Birds of Paradise, Vulturine Parrot, Fairy Lory, Goura Pigeon, Hornbill and Buzzarda | |||

3. | Stone axes | |||

4. | Dog- and marsupial-tooth necklaces | |||

5. | Nonema bead necklaces | |||

6. | Marsupial tails and pelts | |||

7. | Job's Tears necklaces | |||

B. IN 1973-1974 | ||||

1. | Money | |||

2. | Pigs, cassowaries, kina and greensnail shells, steel tools | |||

3. | Plumes of Astrapia, Sicklebill, Lesser, Superb, Saxony, and Raggiana Birds of Paradise, Vulturine Parrot, Papuan Lory, Cockatoo, Paradise Kingfisher, Hornbill, Buzzard, and Harpy Eagle; marsupial skins | |||

4. | Loose fur, chickens, minor shells | |||

a Other plumes, for example, of the Lesser Bird of Paradise, probably fell in this level. | ||||

As noted in chapter 2, most plumes and furs are owned by younger men, as it is they who more keenly participate in dances. Plumes and skins are not used by the Kundagai and other western Maring in major prestations, so that older men who are uninterested in dancing do not generally retain such goods except as trade items. In table 14 I give details of how animal remains recorded in the census of valuables were acquired.

The most common means of acquiring plumes and marsupial skins retained in valuables collections was by gift, followed by trade. By "gift" I mean minor prestations as outlined above. All the marsupial skins listed in the table are low-altitude species unavailable to Tsuwenkai Kundagai hunters by virtue of territorial hunting rights. Concerning bird plumes, trade and loans are more important means of acquiring valuable, or munggoi , plumes than those regarded only as decorations. This is as one might expect, for munggoi items, being more desirable, are more likely to be sought by a trader than are non-munggoi , as they can be used not only for decorations but exchanged for other valuables. In other words, they become commodities as well as decorations and, as such, can be converted into other desirable items. Non-munggoi

TABLE 14. | ||||

Total No. sets | Trade | Loan | Shot | Found |

A. BIRD PLUMES | ||||

All Species | ||||

458 | 120(26.2)b | 14(3.1) | 122(26.6) | 31(6.8) |

Non-valuables | ||||

187 | 29(15.5) | 1 (0.5) | 69(36.9) | 12(6.4) |

Valuables | ||||

271 | 91(33.6) | 13(4.8) | 53(19.6) | 19(7.0) |

B. MARSUPIAL SKINS | ||||

45 | 20(44.4) | 2(4.4) | ||

C. BEETLE SHARDS | ||||

17 | 5(29.4) | 7(41.2c ) | ||

a Refers exclusively to minor prestations. | ||||

b Numbers in parentheses are percentages of row totals. | ||||

c Collected by present owners in swarming season. | ||||

goods do not enjoy such free exchangeability. Gift is almost as important a means of acquiring munggoi as non-munggoi plumes, but hunting is of relatively minor importance in acquiring munggoi plumes, though in large part this is because six of the fifteen munggoi species are not found in Tsuwenkai.

The pattern of acquisition of shells differs from that of other animal products. Partly this is because shells are not of local origin and also because their uses and the categories of men owning them differ. Shells are transferred in large numbers in major prestations in which older men participate. Tables 15 and 16 give details of the ownership of 210 kina and 250 greensnail shells recorded in the collections of all 55 resident adult males. I have not reordered data on the distribution of ownership by age for other shells, as the numbers recorded are small and these shells are now very rarely used in prestations. Gross holdings of these other shells were as follows: 28 sets of Nassa dogwhelk headbands and ropes, most acquired in bridewealth, 3 sets of Cypraea cowry ropes, 8 Conus shell disks, mostly obtained in gifts, and one Melo bailer-shell fragment, acquired in bridewealth.

TABLE 15. | |||||||

Age: | 15-25 | 25-35 | 35-45 | 45-55 | 55-65 | 65-75 | All ages |

Number of men: | 7a | 22b | 11c | 5c | 7d | 3e | 55 |

A. KINA | |||||||

No. men owning | 2 | 21 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 43 |

No. shells | 6 | 111 | 45 | 21 | 23 | 4 | 210 |

Range owned | 0-4 | 0-13 | 0-9 | 1-8 | 0-14 | 0-3 | 0-14 |

Av./total men | 0.8 | 5.0 | 4.1 | 4,2 | 3.3 | 1,3 | 3.8 |

Av./men owning | 3.0 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 2,0 | 4.9 |

B. GREENSNAIL | |||||||

No. men owning | 3 | 17 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 42 |

No. shells | 28 | 109 | 59 | 19 | 24 | 11 | 250 |

Range owned | 0-15 | 0-13 | 3-12 | 3-6 | 0-16 | 0-7 | 0-15 |

Av./total men | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5,4 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 4,5 |

Av./men owning | 9.3 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.9 |

C. KINA AND GREENSNAIL COMBINED | |||||||

No. men owning | 3 | 22 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 47 |

No. shells | 34 | 220 | 104 | 40 | 47 | 15 | 460 |

Range owned | 0-19 | 1-25 | 3-17 | 5-11 | 0-30 | 0-10 | 0-30 |

Av./total men | 4.9 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 5.0 | 8.4 |

Av./men owning | 11.3 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 8.0 | 11.7 | 7.5 | 9.8 |

a Only one of these men is married; he and two others owned all the shells. | |||||||

b Four of these men are unmarried. | |||||||

c All men have at least one living wife. | |||||||

d Includes two widowers. | |||||||

e Only one man with surviving wife. | |||||||

Although plumes and skins are retained primarily for use in decorations or trade, shells are required as major components of prestations. They are also commonly traded but are only minor items of decoration. Consonant with these different social utilities, patterns of ownership and means of acquiring shells differ by age groups from holdings of plumes and skins.

In general one might anticipate that young and old men will own fewer shells as they will tend to be less involved in ceremonial payments, requiring fewer shells for prestations and receiving less. Young unmarried men are not considered to be fully adult, partly because they have not assumed responsibilities for dependents and for the maintenance of amicable relations with affines. As such their need of shell valuables is not great. Old men similarly are often little involved in

TABLE 16. | |||||||||||

Means of Acquisitionb | |||||||||||

Age | No. owninga | No. shellsa | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

A. KINA | |||||||||||

15-25 | 2 | 6 | 3(50.0c | 1(16.6) | 4(66.6) | 1(16.6) | 1(16.6) | ||||

25-35 | 21 | 83 | 16(19.3) | 10(12.1) | 25(30.1) | 3(3.6) | 5(6.0) | 5 9(71.1) | 20(24.1) | 4(4.8) | |

35-45 | 9 | 41 | 11(26.8) | 4(9.8) | 13(31.7) | 6(14.6) | 1(2.4) | 35(85.4) | 6(14.6) | ||

45-55 | 5 | 12 | 7(58.3) | 1(8.3) | 2(16.7) | 1(8.3) | 11(91.7) | 1(8.3) | |||

55-65 | 4 | 23 | 16(69.6) | 2(8.7) | 2(8.7) | 20(87.0) | 3(13.0) | ||||

65-75 | 2 | 4 | 3(75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 4(100.0) | ||||||

B. GREENSNAIL | |||||||||||

15-25 | 3 | 28 | 4(14.3) | 8(28.6) | 12(42.9) | 14(50.0) | 2(7.1) | ||||

25-35 | 17 | 84 | 19(22.6) | 6(7.1) | 21(25.0) | 3(3.6) | 8(9.5) | 57(67.9) | 19(22.6) | 8(9.5) | |

35-45 | 11 | 58 | 20(34.5) | 6(10.3) | 14(24.1) | 3(5.2) | 8(13.8) | 51(87.9) | 7(12.1) | ||

45-55 | 5 | 16 | 5(31.3) | 3(18.7) | 1(6.3) | 3(18.7) | 12(75.0) | 4(25.0) | |||

55-65 | 4 | 24 | 11(45.8) | 2(8.3) | 1(4.2) | 14(58.3) | 10{41.7) | ||||

65-75 | 2 | 11 | 3(27.2) | 2(18.2) | 3(27.2) | 8(72.7) | 3(27.2) | ||||

C. KINA a GREENSNAIL COMBINED | |||||||||||

15-25 | 3 | 34 | 7(20.6) | 8(23.5) | 1(2.9) | 16(47.1) | 15(44.1) | 3(8.8) | |||

25-35 | 21 | 167 | 35(21.0) | 16(9.6) | 46(27.5) | 6(3.6) | 13(7.8) | 116(69.5) | 39(23.3) | 12(7.2) | |

35-45 | 11 | 99 | 31(31.3) | 10(10.1) | 27(27.3) | 9(9.1) | 9(9.1) | 86(88.9) | 13(13.1) | ||

45-55 | 5 | 28 | 12(42.9) | 4(14.3) | 1(3.6) | 5(17.8) | 1(3.6) | 23(82.1) | 5(17.8) | ||

55-65 | 4 | 47 | 27(57.4) | 2(4.3) | 4(8.5) | 1(2.1) | 34(72.3) | 13(27.7) | |||

65-75 | 2 | 15 | 6(40.0) | 2(13.3) | 1(6.7) | 3(20.O) | 12(80.0) | 3(20.0) | |||

TOTALS | 46 | 390 | 118(30.3) | 34(8.7) | 87(22.3) | 20(5.1) | 28(7.2) | 287(73,6) | 88(22.6) | 15(3.8) | |

a Totals in these columns do not equal totals that can be calculated from table 15 since means of acquisition of some shells is unknown. | |||||||||||

b For explanation of categories see text. | |||||||||||

c Numbers in parentheses are percentages of row totals. | |||||||||||

prestations. In part this is the result of their declining interest and ability to participate through age and ill health, but also because sons.., on reaching middle age, assume the exchange responsibilities of their fathers. It follows that married men of middle age can be expected to be most involved with prestations and so to handle larger amounts of shells. This does not necessarily mean that they will hold larger stocks.

Data on shell holdings of fifty-five men are arranged in ten-year-interval age groups in tables 15 and 16. Some clarification of certain tabulated means of acquisition is required. Informants usually specified whether a shell was received in a major prestation—mainly bridewealth and death payment—or as a return gift for such a payment they had made or contributed to. In the first instance, shells were acquired directly from donors or indirectly in redistributions from major recipients. Return payments include three subcategories: direct returns for earlier major prestations by current shell owners; as indirect returns in redistributions from other major recipients; as returns for helping kinsmen make their own major prestations. That is, figures for bridewealth and death payments, and for returns for these two prestations, include shells both distributed between groups making prestations and redistributed within recipient and donor groups. The inclusion of several types of distribution under one heading conforms to Kundagai presentation of information. The "gift" column includes shells passed in minor prestations (munggoi aure awom ) that were not counted as reciprocation for aid in amassing prestations associated with marriage or death.

As suggested, the average number of shells owned by individuals in different age groups varies as does the relative importance of means of acquisition. Most shells are acquired in prestations, although relative proportions vary with age. Trade assumes greater significance as a source of shells for young and, to a lesser extent, old men, with prestations being most significant for men aged between thirty-five and fifty-five. The few shells listed as acquired by "other" means include several taken live from the sea, then cut and polished by their present owners while working on coastal plantations. One man also inherited nine shells from his father. Several dogwhelk collections had also been inherited. Inheritance of shells seems uncommon; on death a man's valuables are normally distributed to kinsmen as part of a death payment.

It is appropriate to note briefly how the age groups employed in the analysis relate to the developmental cycle of men and their households.

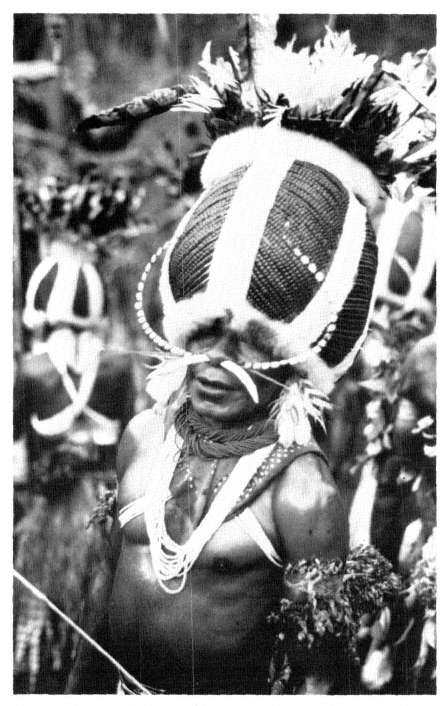

Lucien Yekwai in full dancing regalia. He wears a mamp ku glong wig, decorated

with lines of scarab beetle heads, cuscus fur strips, and plumes of eagle, fowl, and

parrot, and carries a bow in his left hand.

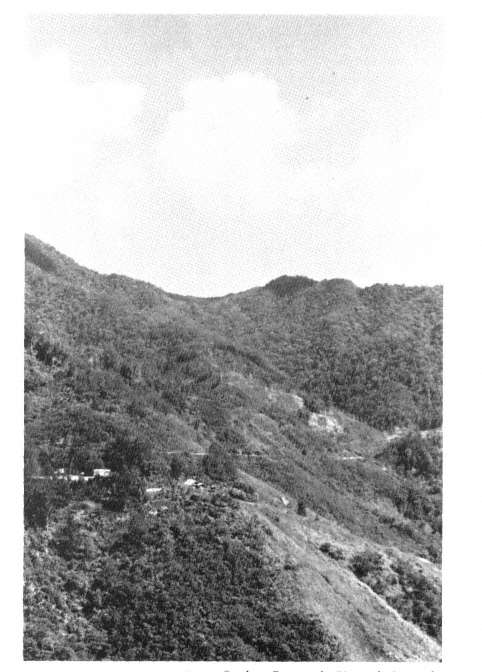

Looking north up the Kant Valley to Gendupa Pass on the Bismarck Crest. The

buildings on the nearer ridge include the ethnographer's house (center) and the

haus kiap (government rest house) located on the edge of the census ground (left).

Note the planted casuarina trees around the census ground, graded walking track

on flank of farther ridge. Newly cleared gardens can be seen at the forest edge at

the head of the valley where the Kant River turns sharply westward. Fallow growth

in the middle altitudes obscures several homestead sites.

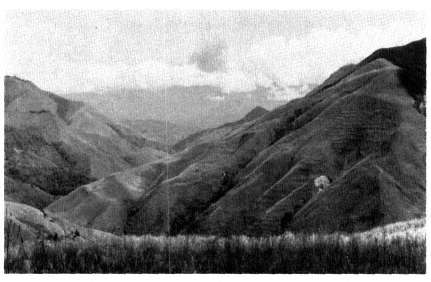

Looking south across the Pint Basin grasslands. The long ridge sloping down from

the right is the north face of Komongwai near the southern border of Tsuwenkai

territory. Kompiai settlement is located on the ridge to the left. The Sepik-Wahgi

Divide lies on the skyline. Note the landslip scar on the flanks of Komongwai and

horizontal marks attributed by the Kundagai to old garden terraces cleared in

grassland before the arrival of steel tools in the 1940s.

Mount Dundunk on the heavily forested Bismarck Crest, seen from a homestead

yard.

Kumbwamp in 1974, aged about 65. She wears a traditional bark cloth cape and

necklace of greensnail shell fragments.

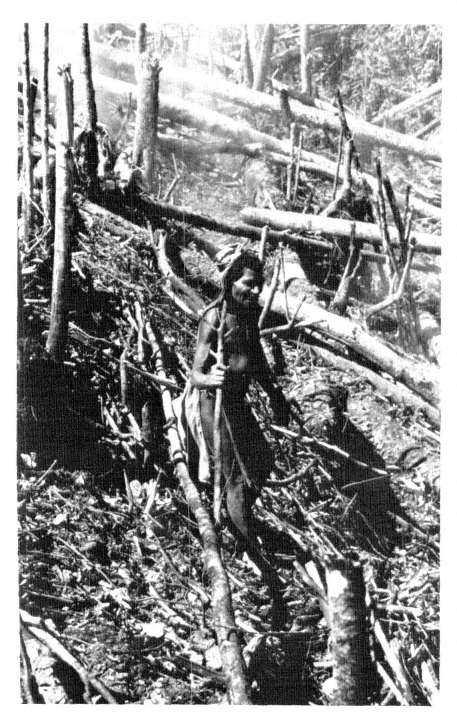

Wande planting a newly cleared garden cut from advanced secondary forest. Burnt

rubbish is still smoking in the background.

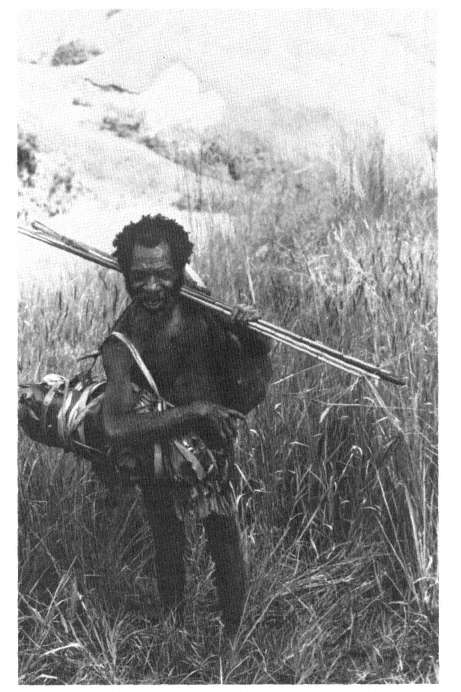

Kamkai returning home from work in his gardens. He carries harvested tubers and

other produce in a bilum (string bag) and improvised bundle carried in the male

fashion slung from the shoulder. Because he has been working in a bush area, he

carries a bow and hunting arrows in case he encounters game. He has hitched up

his apron for ease of movement in thick undergrowth.

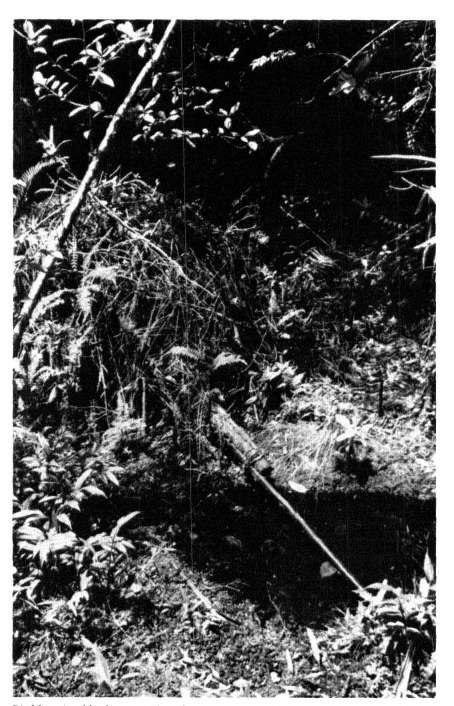

Bird hunting blind at a pool in the high altitude forest. The blind has been abandoned

for some time and is in disrepair, with its heavy leafy covering largely rotted

away revealing the domed structure. A bark tube to guide an arrow to its mark

protrudes through the blind wall bound to the top of the pole that serves as a

perch.

Sacrifice of a large pig for a bridewealth presentation in a raku , sacrificial grove

and cemetery.

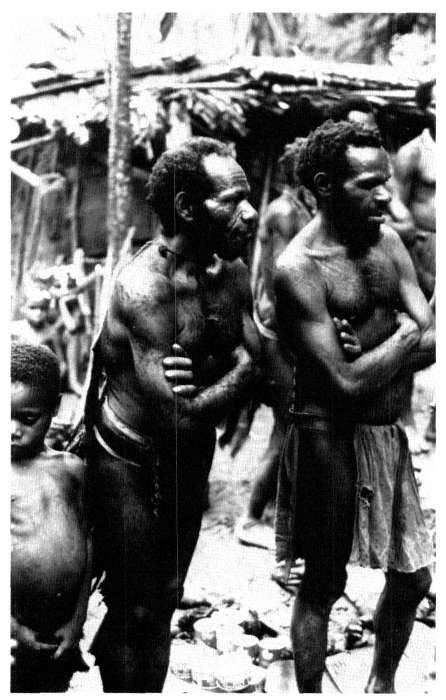

Spectators at a bridewealth presentation in 1974. The low, turtle backed house in

the background, roofed with pandanus fronds, is typical of Tsuwenkai houses.

Part of a bridewealth presentation on display, 1974. Greensnail shells are arranged

at the far end, kina, flanked by lines of paper money on the left (the arrows are

to prevent the money from blowing away, and are not part of the presentation),

axs and bushknives to the right. Joints of cooked pork are on display in a separate

pile out of the photo.

After presentation of bridewealth the bride and her companion emerge from se-

clusion. She is heavily decorated, mainly with parrot feathers. In her left hand she

waves a Lesser Bird of Paradise plume and carries a joint of pork in her right hand

as gifts for her husband's kin. This practice of presenting a heavily decorated bride

has been adopted recently from Kuma-speaking areas of the upper Jimi.

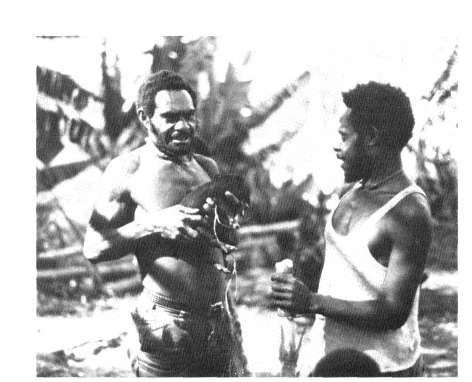

Giewai displays Harpy Eagle feathers he hopes to exchange for money with a party

of visiting traders from the upper Jimi.

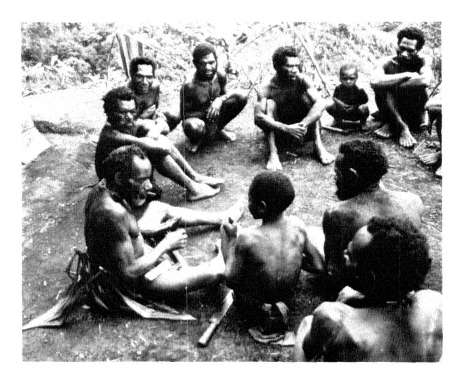

Kemba (left) displays money (folded on his thigh) to a group of fellow Kundagai.

He has been given the money by a trade partner in the Simbai Valley who asked

Kemba to get him a pig.

John Kandemungu (left) ponders the merits of a piglet a visiting trader from Togban

(right) wishes to exchange for money. The visitor holds a stick of sugarcane he

has been offered in hospitality.

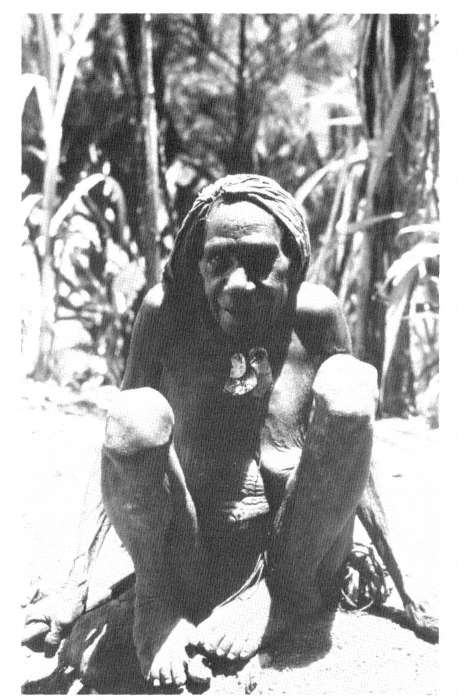

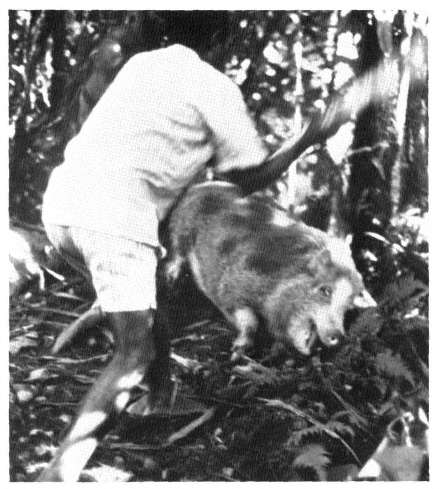

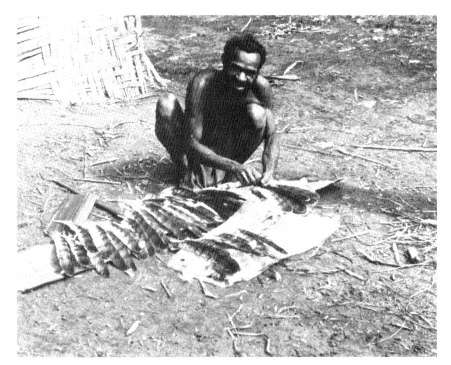

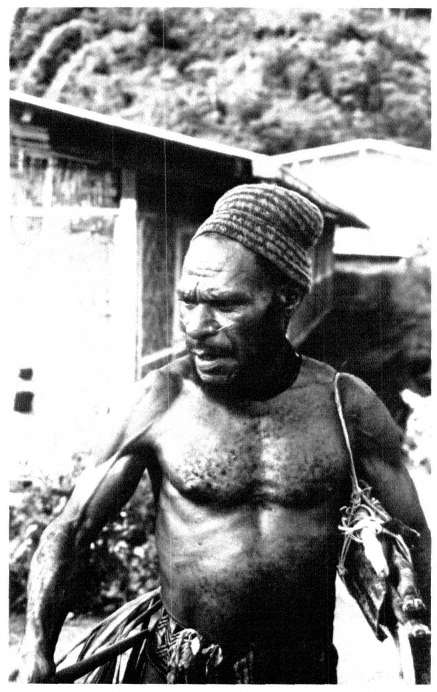

Itinerant pig trader from south of the Jimi River at festivities hosted by the Angli-

can Mission at Koinambe, Christmas 1973. Note his traditional decorations of

netted cap, slivers of bamboo in nose, and woven belt. He carries the piglet he

wishes to exchange for plumes slung in a bark roll from his shoulder. The piglet's

trotters can be seen protruding from its wrapping.

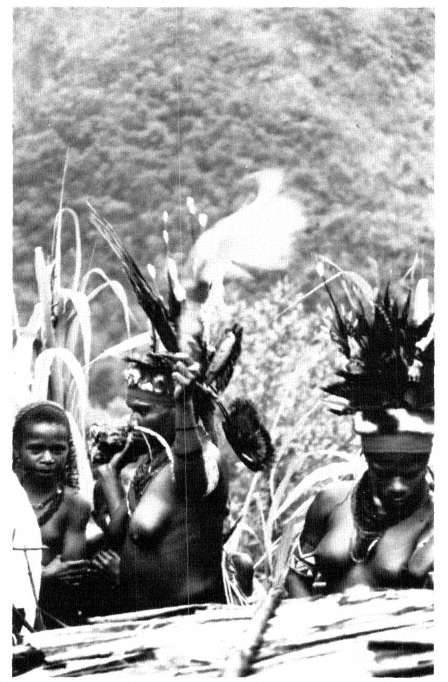

Dance contingent and spectators at a pati held in Tsuwenkai, 1974. The building

in the background is a temporary shelter for visitors. The man in the right fore-

ground has a Lesser Bird of Paradise plume in a bamboo tube he wishes to trade.

The fifteen to twenty-five age group represents young adults, the bulk of whom are bachelors attached to the households of their fathers, elder brothers, or other senior cognatic or affinal kin. The next three age groups (from twenty-five to fifty-five) represent predominantly married men with responsibilities for one or more wives, growing numbers of children, and perhaps unmarried siblings, widows of kinsmen, aging parents, and other kin. As a man approaches middle age his responsibilities for dependents tend to increase and he becomes more involved in a network of exchanges flowing from both his own marriage as well as those of other clansmen. By the time he is in his late forties or early fifties a man's conjugal family will begin to break up, with the marriage of his children. Relatively few men in their late fifties have continuing responsibilities for young children, and their exchange obligations and care of dependents have frequently been assumed by sons or younger brothers. Thus, the last two age groups represent old men, most of whose households have dissolved and who have been incorporated into the households of a younger generation of mature men.

A large proportion (all unmarried) of men under twenty-five own no shells at all. Of those that do, their stocks of kina are lower than of any other age group, although holdings of greensnail approximate the average for all age groups combined. Bridewealth forms the most important means of acquiring kina, whereas trade is the major means of obtaining greensnail shells. Most greensnail coming by trade were bought while their owners were on contract labor near Rabaul. Men of this youngest group are a significant source of new greensnail brought from beyond the locally based spheres of exchange. Kina are less often brought home in this way. It is mainly such younger men who go to work in distant areas.

Men of the twenty-five to thirty-five age group retain the largest stocks of shells. Bridewealth and trade are the most significant means of acquisition. Men in the thirty-five to forty-five age groups gain most shells in bridewealth and death payments but rely least heavily of all ages on trade for their supplies.

In the forty-five to fifty-five age group the average size of shell stocks is below the mean for all age groups combined. Receipt of bridewealth and death payments and return gifts for these are the most important means of acquiring shells. These means become more marked for the oldest two age groups.

There are two peaks of the average number of shells owned: in the fifteen to twenty-five and fifty-five to sixty-five age groups. The peak in

the younger group can be explained by their acquiring shells by trade, whereas the older group receives some by trade but most (57.4 percent) in bridewealth, mainly for their daughters. Most women are probably married when their father.,; are in this age group.[3]

If average shell stocks are calculated on the basis of all men in an age group, rather than the number of men owning shells, then the largest collections are held by the twenty-five to thirty-five age group, with stocks decreasing thereafter with age. This pattern may be accounted for as follows. Men between twenty-five and thirty-five are amassing shells for their own initial bridewealth payments. Indeed, at the time of the valuables census, several men in this group stated that they had many shells because they were about to give bridewealth. Although this group receives only 21 percent of their stocks in bridewealth, mainly for clan sisters, they are evidently receiving many shells in return for their own bridewealth payments and in return for helping kinsmen, mainly agnates, in making bridewealth payments. Of all age groups, they receive the largest proportion of their stocks in the form of return gifts associated with bridewealth.

Bridewealth increases in importance as a means of acquiring shells up to the age of sixty-five, but return gifts associated with bridewealth decrease in importance. 'This is because the major contributors to bridewealth payments tend to be younger men, whereas older men give smaller and receive larger proportions of shells by this means. Men between forty-five and fifty-five, by contrast, are the major recipients of death payments and return gifts for death payments. Such payments are mainly received for deceased married sisters and their children and for their father's sisters and father's sisters' sons and unmarried daughters. Men in the oldest age group, who are often real or classificatory fathers to men of the forty-five to fifty-five age group, are also the main recipients of death payments for the latter category of deceased males and unmarried women, who are sisters' children.

These data concern only shells currently held in personal collections. I have no comparable material on the number of shells or other valuables that men may have distributed in prestations or contributed to major exchanges of other men, and for which returns are outstanding. Indeed, this would be a fruitless exercise of computation for the ethnographer and Kundagai alike, as one can never be certain that valuables will be reciprocated in equal quantities and worth, or when, if at all. Some shells I saw in collections were already earmarked to settle existing debts. The number of shells a man may expect to exercise rela-

tively autonomous control over therefore is indeterminate and does not necessarily include all in his possession but may include some in the custody of others.

Notwithstanding these considerations, the material on existing shell stocks can be used as a basis to suggest the means of loss of shells. Although men aged twenty-five to thirty-five receive relatively few shells in bridewealth, they receive the largest proportion of all age groups in return gifts for bridewealth. Men of these ages are most active in giving bridewealth, and the large amounts they receive in return gifts reflect this. Similarly, men aged forty-five to fifty-five are not only receiving large proportions of shells in death payments but pay out substantial death payments for parents and young children. In the census of valuables, return gifts for death payments exceed receipt of death payments. As not all death payments are countered by a return gift (see below), it is probable that many of the return gifts listed are from other men whom shell owners have helped to make payments, rather than as returns for presentations their owners have made as principal donors. Men over fifty-five years old have received no shells as return gifts for death payments, and few as return gifts for bridewealth payments, which suggests that they contribute little to such prestations. This conclusion is borne out by my observations on contributions to such prestations that occurred during fieldwork.

Bridewealth becomes increasingly important with age as a means of acquiring shells, but the fact that the size of shell stocks decreases with age indicates that losses of shells, mainly in death payments in middle age and as contributions to sons' bridewealth payments which are not replaced by return gifts,[4] exceeds the acquisition of shells with advancing years. Accumulation through trade is most important for younger men and of secondary importance for men over forty-five. The latter are perhaps attempting to replenish their stocks, which are declining through prestations that are not fully reciprocated.

Regardless of age, bridewealth and associated return gifts are the most important means of acquiring shells (55.6 percent combined), with trade being next in importance. Shells received in death payments and associated return gifts are of lesser numbers, if only because death payments are smaller than bridewealth.

Nine of the fifty-five men whose shell collections I examined are big-men. Two of these (in the forty-five to fifty-five and sixty-five to seventy-five age groups) are politically influential tep yu ("Talk Men"). The other big-men are bamp kunda yu ("Fight Magic Men") and

mengr yu ("Shell Men") who are not outstanding in political affairs. The older tep yu owns more shells than the average for his age group and slightly more than the average for all shell owners irrespective of age. The younger tep yu owns fewer shells than these averages. Most remaining big-men own stocks approximating averages for their age groups. Greatest variations are two men owning no shells and one owning thirty shells. There is, then, a wide range in the collections of big-men, but there is no strong evidence to suggest that they tend to possess more shells than other men. I doubt that big-men as a category have created more outstanding debts by contributing to other men's prestations than have other men, although the younger tep yu may have done so. It is reasonable to conclude that big-man status of itself does not necessarily correlate with personal wealth.

I obtained no ordered data on the ownership of steel tools. Most men own several axes and knives, but they are often all used for everyday tasks, even if one tool is favored above others. Thus, steel tools are seldom stored in separate bundles like other valuables and, if not in immediate use, are propped up inside doorways or wedged into house walls. One man aged about thirty had a bundle of thirteen axes stored. in his house. Another man of about forty-five had five axes. While on contract labor in coastal centers most men buy several steel tools for use in their own bridewealth payments or to distribute as gifts to male and female kin. Steel tools are also bought from stores in Tabibuga, Koinambe, and Simbai Patrol Post and are usually purchased by younger men collecting bridewealth payments. Steel is also commonly traded between settlements. Most such tools, however, change hands in prestations.

I attempted to determine the size of the Kundagai pig herd on two occasions: during the population census at the beginning of fieldwork and again in late September 1974 . During the population census I simply asked men the number of pigs they owned. I did not see all animals, therefore, and, although I know at least some men gave accurate figures, some errors were inevitable by this method. The Kundagai do not appear to be secretive about the number of pigs they own, unlike, for instance, the Mae Enga (Meggitt 1974: 168, n. 8). Nor do kinsmen in other settlements agist pigs for the Kundagai to any significant extent.

A man generally divides his pigs among his wives and older unmarried daughters to care for. If his herd is larger than these dependents can care for on their own, he may assign some pigs to the care of mar-

ried sisters or his mother resident in Tsuwenkai, or to male kin who in turn assign them to their own female dependents.

In January 1974 the Kundagai pig herd was counted at 243 animals, which is no doubt an underestimate. At the end of September 1974 the number of pigs was 311. This latter count is more accurate.[5] It excludes pigs agisted outside Tsuwenkai, though probably no more than 12 animals are involved. The total includes piglets, but I do not know the age or sex structure of the pig herd. Table 17 shows the distribution of ownership of pigs by age and sex as of September ]974.

All males over about fifteen years old are potential pig owners, though few adolescents actually own beasts. Almost every male over the age of twenty-five owns at least one pig, whatever his marital status. Women do not normally own pigs over which they can expect full rights of disposal. Of the three women owning pigs, the youngest is a remarried widow whose husband lives in Bokapai with his first wife. The older woman is a vigorous and independent co-wife of a mengr yu big-man. Her two pigs were a gift from a daughter's husband. The remaining woman is a non-Kundagai widow with several young children. She lives in the homestead of her husband's brother.

All married men owned at least one pig, while one man owned as many as fourteen. On marriage a man will often be given a pig by his father or an elder brother for his wife to care for. A woman with no pigs under her charge will complain to her husband.

The size of an individual's pig herd shows an increase up to the forty-five to fifty-five age group, after which the size of herds falls. Two of the twenty-two unmarried pig owners are likely to remain permanent bachelors, as informants say no woman would consent or be expected to marry them. One, aged about thirty, is considered plim , "mad," the other aged forty to forty-five, a notorious kwimp , "witch."

Men between thirty-five and fifty-five own the largest pig herds. This may be explained by the tendency of men of these ages to support the greatest number of female dependents who can care for their pigs. Most polygynists with both wives surviving are in this age range. It is also between these ages that a man generally will have the greatest number of unmarried younger sisters or daughters to help his wife or wives and widowed mother to care for his pigs. Once a man's sisters or daughters are married they will be caring for their husband's pigs and, even if they remain within their natal settlement, the number of further pigs belonging to agnates which they can care for decreases. Thus, older men are often unable to find sufficient guardians to maintain large pig herds.

TABLE 17. | ||||||||||||

Age | A. No. | B. No. | No. | Average owned | Married | Unmarried | Widowed | |||||

potential owners | owning | pigs | per A | per B | No. owning | Av. owned | No. owning | Av. owned | No. owning | Av. owned | ||

A. MALES | ||||||||||||

15-25 | 27 | 15 | 46 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 1 | 5.0 | 14 | 2.9 | |||

25-35 | 31 | 30 | 130 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 23 | 4.6 | 7 | 3.4 | |||

35-45 | 13 | 13 | 69 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 12 | 5.7 | 1 | 1.0 | |||

45-55 | 5 | 5 | 29 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5 | 5.8 | |||||

55-65 | 7 | 5 | 19 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 4 | 4.5 | 1 | 1.0 | |||

65-75 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 1 | 4.0 | 2 | 3.5 | |||

SUB TOTAL | 86 | 71 | 304 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 46 | 5.0 | 22 | 3.0 | 3 | 2.7 | |

B. FEMALEa | ||||||||||||

25-35 | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.0 | |||||||

35-45 | 1 | 4 | 4.0 | 1 | 4.0 | |||||||

45-55 | 1 | 2 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.0 | |||||||

SUB TOTAL | 3 | 7 | 2.3 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 4.0 | |||||

C. TOTALSa | 74 | 311 | 4.2 | 50 | 4.6 | 22 | 3.0 | 4 | 3.0 | |||

a It is unusual for women to own pigs in their own right, and so potential number of female pig owners has not been shown. | ||||||||||||

Younger unmarried men are in a similar position. They rely upon unmarried sisters, mothers, or brothers' wives to care for their pigs. All these women may also have responsibilities for other men's pigs. There seems to be only a minor tendency for big-men to own slightly more pigs.

The average number of pigs per owner (male and female) is 4.2. This compares well with data Meggitt (1974: 168, n. 8) gives on Mae Enga pig holdings, where the average number of pigs per owner varies from about 1.9 for bachelors to 5.4 for married men, with a mean of 4.1 for all owners. (The equivalent figures for the Kundagai are 3 pigs for bachelors and 5 for married men.) Meggitt suggests his ratios are underestimates, as the Mae Enga are reluctant to reveal the number of pigs they own.

The ratio of Kundagai pigs to the total resident human population is also high by highland standards. In September 1974 there were 1.1 pigs to I person. This compares with 0.83 to I among the Tsembaga when the pig herd was at its maximum prior to their 1963 konj kaiko (Rappaport 1968: 93) (see table 19 for other Maring ratios). Ratios in the central highlands range from about 1 to 1 to 3 to 1 (Feachem 1973). It is clear, then, that the Kundagai cannot be considered poor in pigs. Although the much denser human populations of the central highlands mean that their pig populations are also much larger, it is unlikely that Kundagai husbandry practices and the work burden of women would permit a much larger pig herd. Nonetheless, informants were of the opinion that the Kundagai herds were larger prior to the last konj kaiko in 1960, although I cannot evaluate this statement. The herd is maintained at a lower level now, they say, as pigs are more frequently killed for damaging food and coffee gardens and are killed periodically to be butchered and sold for cash within Tsuwenkai. Such killings are now an important means of depleting the pig herd. Major prestations often include joints of cooked pork from one or more large pigs, while celebratory feasts and sacrifices to the spirits to cure sickness account for most other pigs. Table 18 lists the number of pigs killed during fieldwork and the principal reasons.

In addition, at least five adult or subadult pigs died of sickness or were killed by other pigs during fieldwork. An unknown number of piglets died, mostly from apparent intestinal infections. Several of the larger pigs were eaten, two being cut up for sale.

To the time of the September pig census fifty-nine pigs were killed, or nineteen percent of the then total population. If no further pigs were

TABLE 18. | ||

Principal Reason for Killing | Number | |

1. Bridewealth & other affinal prestations | 16 | |

2. Death payments | 2 | |

3. Termination of widow's mourning | 6 | |

4. Removal of food and fire taboos (in association with widowremarriage) | 1 | |

5. Sacrifice in sickness | 3 | |

6. Adultery compensations | 2 | |

7. Celebratory feasts | ||

a. return of migrant workers | 6 | |

b. for Bishop on opening of new Tsuwenkai church | 2 | |

c.for Healeys on departure from field | 3 | |

8. Garden or house raiding | 10 | |

9. Run wild | 3a | |

10. For killing other pig | 1 | |

11. For butchering and sale | 11b | |

TOTAL | 66 | |

a One agisted in Tsuwenkai for a Kinimbong man. | ||

b All or part of at least 10 pigs killed for other reasons also put on sale. | ||

acquired before November (as I suspect was the case), the loss rate of pigs by killings was 21.2 percent. The number of live pigs lost from the Tsuwenkai herd was small. Most such losses were of piglets imported by trade and then quickly exported again.

Buchbinder (1973: 131) gives figures for the number of pigs killed by several Simbai Maring populations in 1968. Comparative data are given in the following table.

These data indicate that the size of the Kundagai pig herd relative to human population is similar to ratios in other Maring settlements. The Simbai Maring are further comparable with the Kundagai in that none were collecting pigs for a konj kaiko (Buchbinder 1973: 130). A ratio of about one pig per person therefore appears to be the general size of contemporary Maring pig herds. In 1968, however, no Maring population approached the Kundagai slaughter rate. The collective kills of the Bomagai—Angoiang and Funggai—Korama clan clusters of Gunts made up the highest slaughter rate. The average proportion of pig herds killed annually for the nine Simbai populations was 9 percent.

The greater rate of killing in 1973-1974 no doubt reflects an increase in the number of pigs killed for butchering and sale. Money was still scarce in the Simbai in 1968. My presence in Tsuwenkai as a ready source of cash undoubtedly encouraged the killing of pigs for sale. If

TABLE 19. | |||||

Population | Resident human population | Pig population | Pig-per- | No. pigs killed | Percent of herd killed |

Tsuwenkai Kundagai | 273 | 311 | 1.1 | 66 | 21.2 |

Kinimbong Kundagai | 113 | 148 | 1.2 | 14 | 9.5 |

Tsembaga | 206 | 209 | 1.0 | 16 | 7.6 |

Tuguma | 253 | 232 | 0.9 | 24 | 10.3 |

Kanump-Kauwil | 342 | 354 | 1.0 | 15 | 4.2 |

Kandarnbent-Namikai | 321 | 319 | 1.0 | 14 | 4.4 |

Ipai-Makap | 220 | 197 | 0.9 | 17 | 8.6 |

Tsenggamp-Mirimbikai | 90 | 180 | 2.0 | 23 | 12.8 |

Bomagai-Angoiang & Funggai-Korama | 293 | 297 | 1.0 | 51 | 17.2 |

Kono | 121 | 113 | 0.9 | 10 | 8.8 |

MEAN | 223.2 | 236 | 1.1 | 25 | 10.6 |

a Data other than for Tsuwenkai from Buchbinder 11973). | |||||

these animals are excluded from the table, then 17.6 percent of the Tsuwenkai herd was killed. This is only slightly above the highest rate of slaughter in the Simbai in 1968. If kills for such rare events as celebratory feasts for the diocesan bishop and other visitors are also excluded, then 16.1 percent of the herd was killed. This is still a high slaughter rate.

To maintain their pig herd in the face of high slaughter the Kundagai would need to increase the recruitment rate of the herd. The major means of achieving this are by import of live pigs and a reduction of export of locally raised pigs[6] Medicines are sometimes acquired from agricultural officers at the Tabibuga government station, which help reduce pig mortality through sickness. Considerably increased import of young pigs has probably been the major factor in allowing greater rates of slaughter. I doubt, however, that pigs are often kept until they reach full size, and this may be important in permitting a sustained rapid turnover of the pig population. Indeed, a feature of the present pig herd is that it appears to be maintained at near-maximum size. Formerly, and still so among those Mating populations yet to stage konj kaiko ceremonies, pig herds went through long cycles of slow increase to maximum densities followed by massive slaughter at the end of the ritual cycle (Rappaport 1968). The present Kundagai strategy may have serious ecological consequences yet to be determined. However,

assuming that fewer pigs are allowed to reach maximum size (and certainly I saw few very large pigs), the overall live-weight of the herd at maximum numbers permitted by the capacity of women's labor to sustain them may be considerably less than that of a herd immediately prior to a konj kaiko . In short, the demographic pressure of the Kundagai and their pigs may be less than that of a comparable population approaching a kaiko .

Small numbers of live piglets are lost from the herd in trade, gifts to affines or occasionally as return gifts for bridewealth or death payments. Most pigs are nonetheless lost as pork rather than live. The same holds for the Narak and Kalam neighbors of the Maring. Unlike many parts of the central highlands where ceremonial payments may include relatively large numbers of live pigs, losses from a Maring herd do not swell the herds of recipients[7] One is led to conclude, therefore, that notwithstanding the periodic large pig kills among central highlanders, there is probably a more rapid turnover of pigs among the Mating and their neighbors. Even if Maring pig fertility is similar to that in the central highlands it is unlikely that reproduction is sufficient to maintain the Kundagai pig herd at its present size without considerable import of live pigs, mainly effected through trade,[8] a matter to which I return briefly in chapter 7.

Kundagai stocks of other livestock are low. Two men owned one cassowary each during the period of major fieldwork. One of these birds was killed as a sacrifice to the spirits during the illness of the owner's wife. Three men owned four dogs, two of which had litters. Most householders own fowls, but their numbers are few.