Four

"Alien Yet Inviolably Durable

The Folk Architecture of Yoknapatawpha

"Folk," "vernacular," "primitive" architecture pervades Faulkner's world, buildings that elude and transcend chronology and that reach from the earliest times into the twentieth century. They are hard, tough structures, symbolic for Faulkner not only of the meanness of life for some, but of the patience and persistence and endurance of the people who built and used them. Originally such buildings were of logs, notched at the corners, a technique similar to that used in various Native American structures. In its European form, log construction was brought across the Atlantic not by the British but by German and Scandinavian immigrants, who settled in the eastern colonies and passed on their log building techniques to English- and African-Americans as settlement pushed west and south in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

"The first houses in new areas of settlement were usually crudely constructed," historian James Latham has noted. "These were temporary, to be used only until something more substantial could be built." There was a great difference between the early, one-room "log cabin," an Irish term, and the more permanent and technically and socially substantial "log house." Spatially, the basic form of the Southern folk house was the so-called single pen, a rectilinear, one-room log structure whose short side averaged some seventeen feet as compared with the long side of approximately twenty feet. It had a gable roof with a single chimney centered along one of the gable ends. Front and back doors were usually centered opposite each other in the two long sides. [1]

Figure 14

Dogtrot House, Lafayette County, Mississippi (nineteenth century).

When it became necessary to enlarge such houses, the usual method was to add a similar structure to one of the gable ends. If the addition occurred at the end opposite the chimney, the structure, now composed of two single pens, was logically called a "double pen house," with separate front entrances into the two rooms and a second end chimney in the center of the new gable. If the addition to the single pen was made to the chimney end, the resulting "saddleback house" had a central chimney that served both rooms, while usually retaining the double-pen practice of separate entrances from the porch. Since there were obvious difficulties in adding to notch-cornered log structures, the simplest solution frequently was to connect two single pens by an open passageway, with the passageway and both houses covered by one continuous roof, forming the popular "dogtrot" house (Figs. 14, 15, and 17). [2]

In addition to the technical rationale for constructing them that way, the open breezeway of the dogtrot house was a pleasant place for sitting and socializing, and the type became a ubiquitous building form, not only in the countryside but, in its formative years, of the Southern town as well. It was also referred to as a "dogrun," a "possumtrot," and "two pens and a passage." Like the single and double pen and the

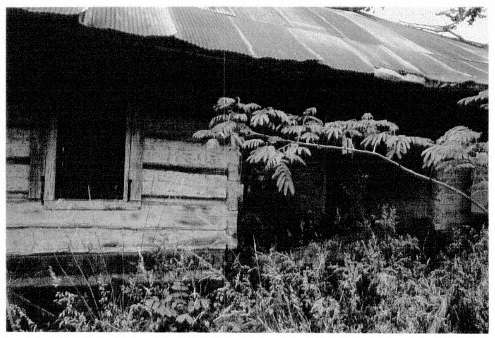

Figure 15

Dogtrot House, Lafayette County, Mississippi (nineteenth century), photograph by Martin Dain.

saddleback house, moreover, it continued as a building type long after notched-log buildings gave way in the middle and later nineteenth century to the so-called "balloon frame," a form and a technique made possible by the new combination of recently invented metal nails, readily planed lumber, and, with the coming of the railroad, easily shipped planks. Sometimes older log structures were covered over and "remodeled" with such boards.

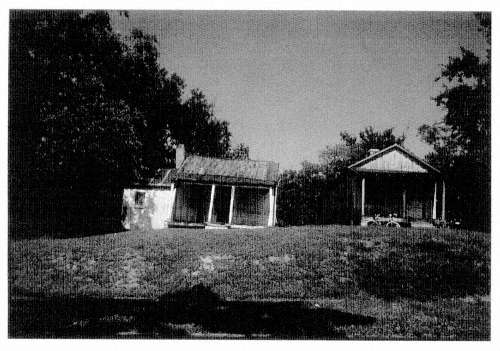

The dogtrot house could also be expanded into much grander forms, with the open passageway enclosed as a front stairhall to a new second floor. Such greatly enlarged houses might then be graced with a two-storey portico across all or part of the front facade, becoming in the process a homegrown version of the neoclassical house. This development characterized the houses of several prominent Oxford families whose histories Faulkner knew. They included the one-storey home, later named "Lindfield," of David Craig (ca. 1837), one of the early settlers of Oxford, a house located two blocks from the larger Shegog House (1848), which Faulkner would purchase in 1930 and live in the rest of his life. A rude, double-pen log house was also the basis of the home of another pioneer, Samuel Carothers, who later enlarged the house into a stately, two-storey dwelling with a six-columned portico across the front. In 1847, Dr. Thomas Dudley Isom, another of the town's earliest settlers, acquired the house and continued to improve and embellish it (Fig. 16). [ 3] Indeed, the transformation from humble necessity to neoclassical grandeur epitomized the social ascendancy of a number of Faulkner's most vivid fictitious characters.

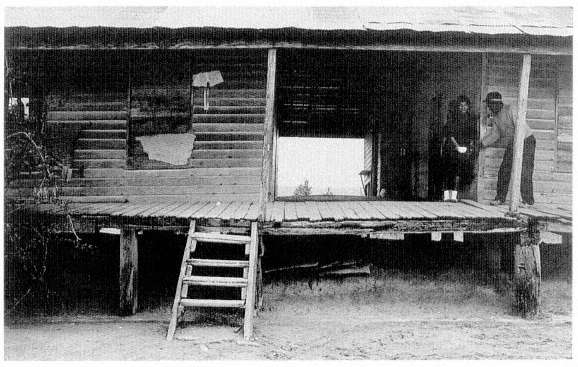

Still, un enlarged folk buildings, inhabited by both black and white Mississippians, were even more familiar structures in Faulkner's world, particularly in the Snopes trilogy. In The Mansion , ironically, a dogtrot house lay on a road marked with many wheels and traced with cotton wisps, yet dirt, not even gravel, since the people who lived on and used it had neither the voting power to compel nor the money to persuade the Beat supervisor to do more than scrape and grade it twice a year. So what he found was . . . what he had expected: a weathered, paintless dog-trot cabin enclosed and backed by a ramshackle of also paintless weathered fences and outhouses —barns, cribs, sheds —on a rise of ground above a creek-bottom cotton patch where he could already see the whole Negro family and perhaps a neighbor or so too dragging the long stained sacks more or less abreast up the parallel rows . (Fig. 17). [4]

In The Hamlet , the first volume of the trilogy, critic Michael Millgate argues, Faulkner's description of Mink Snopes's house is "important for its own sake, as an additional facet of the analytical portrait of the area, but it is also crucial to our understanding of Mink himself and of the reasons why he murders Houston. Thus there is obvious dramatic point in the utter poverty of the place being evoked through the eyes of Mink

Figure 16

Carothers-Isom House, Oxford, Mississippi (1843 and later).

himself as he returns from the murder." It was dusk. He emerged from the bottom and looked up the slope of his meagre and sorry corn and saw it—the paintless two-room cabin with an open hallway between and a lean-to kitchen, which was not his, on which he paid rent but not taxes, paying almost as much rent in one year as the house had cost to build; not old yet the roof of which already leaked . . . just like the one he had been born in, which had not belonged to his father either (Plates 2 and 3). [5]

Later still, Millgate contends, as Mink is being taken to jail in Jefferson, "his own background is implicitly evoked in terms of his awareness . . . of the trim and prosperous world of Jefferson." The comparison is shattering: the surrey moving now beneath an ordered overarch of sunshot trees, between the clipped and tended lawns where children shrieked and played in bright small garments in the sunset and the ladies sat rocking in the fresh dresses of afternoon and the men coming home from work turned into the neat painted gates, toward plates of food and cups of coffee in the long beginnings of twilight . Compared to the environment in which he had spent his life, this world, however enviable, was alien to Mink. It was a milieu he could never imagine entering, though one into which his more resilient cousin, Flem, would cunningly ingratiate himself. [6]

Figure 17

Dogtrot House, Lafayette County, Mississippi (nineteenth century).

In As I Lay Dying , much the same kind of implicit social and architectural comparison occurred in Addie Bundren's posthumous trip to the Jefferson cemetery from the farm on which she had lived. There a cotton house had been made of rough logs, from between which the chinking has long fallen. Square, with a broken roof set at a single pitch, it leans in empty and shimmering dilapidation in the sunlight, a single broad window in two opposite walls giving on to the approaches of the path .[7]

Mildly updated versions of such structures would continue to appear on the outskirts of Jefferson into the twentieth century, with subtle markings in their maintenance and accoutrements, demarcating race and class. In Knight's Gambit , young Benbow Sartoris, on leave from the Army Air Corps in 1942, observed such houses as he returned by train to Jefferson. He sensed that the train was beginning to pass the familiar land: the road crossings he knew, the fields and woods where he had hiked as a cub then a scout. . . . Then the shabby purlieus themselves timeless and durable . . . the first Negro cabins weathered and paintless until you realized it was more than just that and that they were a little, just a little awry, not out of plumb so much as beyond plumb: as though created for, seen in or by a different perspective, by a different architect, for a different purpose or anyway with a

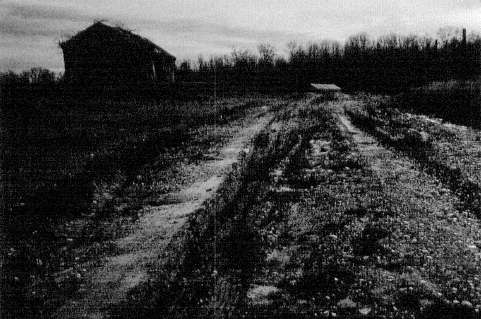

Figure 18

African-American working-class houses, Holly Springs, Mississippi (early twentieth century).

different past . . . each in its fierce yet orderly miniature jungle of vegetable patch . . . and usually a tethered cow and a few chickens, the whole thing—cabin outpost washpot shed and well having a quality flimsy and make-shift, alien yet inviolably durable like Crusoe's cave; then the houses of white people, no larger than the Negro ones but never cabins, not to their faces anyway or you'd probably have aright on your hands, painted or at least once painted, the main difference being that they wouldn't be quite so clean inside (Fig. 18). [8]

Yet such dwellings also recall the very beginnings of Jefferson, as described in Faulkner's Compson appendix to The Portable Faulkner: a solid square mile of virgin North Mississippi dirt as truly angled as the y our corners of a cardtable top (forested then because these were the old days before 1833 when the stars fell and Jefferson, Mississippi was one long rambling one-storey mudchinked log building housing the Chickasaw agent and his tradingpost store) .[9]

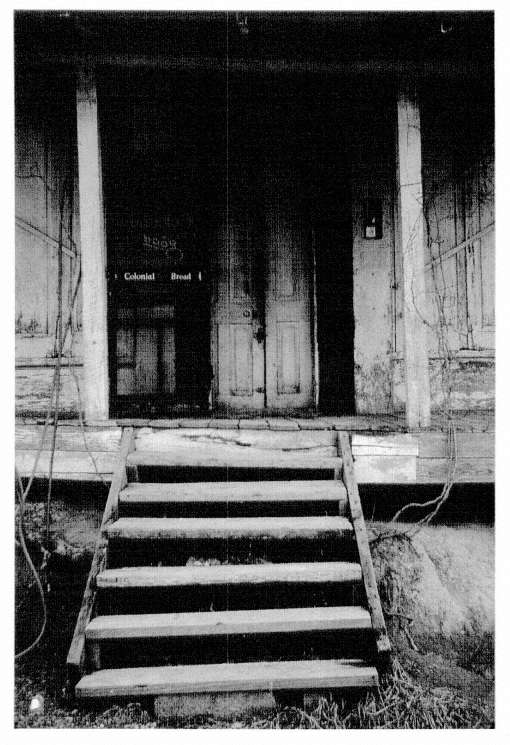

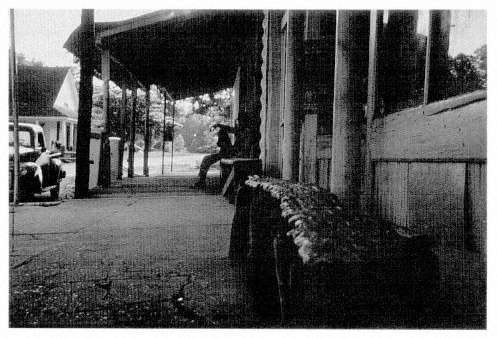

Stores of all varieties were crucial in Faulkner's work: social as well as commercial structures, places to see and meet other people, to transact business, personal and professional; important stages in Faulkner's world of comings and goings for the most rural people whose visits to such places constituted a primitive window on a larger

Figure 19

College Hill Store, steps and door, College Hill, Mississippi (late nineteenth century).

world. The store in the hamlet of College Hill, northwest of Oxford, dated originally from the late nineteenth century and remained unchanged through the mid-twentieth century—except for the modernist intrusion of the red gas pump outside (cover and Fig. 19). The College Hill Store was used by MGM as an important set location in its filming of Faulkner's Intruder in the Dust . Descriptions of stores in Intruder, The Hamlet , and various stories evoke the penumbral attributes of buildings, especially the smells, much in the manner of Proust's Remembrance of Things Past . In "Barn Burning": The store in which the Justice of the Peace's court was sitting smelled of cheese. The boy, crouched on his nail keg at the back of the crowded room, knew he smelled cheese, and more: from where he sat he could see the ranked shelves close-packed with the solid, squat, dynamic shapes of tin cans whose labels his stomach read .[10]

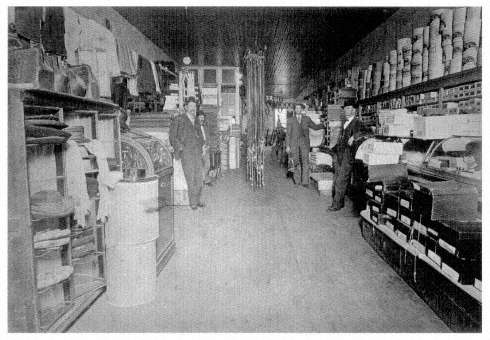

Faulkner somehow failed to characterize the oldest, largest, and most important small-totem store in north Mississippi, the upscale J.E. Neilson Company, founded in 1839 by one of Oxford's oldest and most prominent families. He seemed to be drawn to its smaller, more rural variants, as typified in such establishments as D. Pointer and Company, in nearby Como, Mississippi (Figs. 22-26). In The Hamlet , Faulkner described a store's now deserted gallery, stained with tobacco and scarred with knives . The reference to knives may have come from his familiarity with a store in the hamlet of Taylor, Mississippi, south of Oxford, where old men's, possibly absent-minded, pocketknife whittling had nearly carved away the wooden benches in front (Fig. 20). Faulkner's notable talent for compiling elegant lists reached its apogee in describing the interiors of such stores, as for example in the Compson appendix to The Portable Faulkner , where in 1943 the town librarian seeks out Jason Compson to show him a color picture in a glossy magazine of his prodigal sister, Caddy, photographed with a Nazi general staff officer. Here again, in his inimitable way, Faulkner made his point with a coruscating contrast between Caddy's corruptly elegant, high-profile notoriety and the dusty layers of the hometown store where her brother's "office" was housed. In this passage, Faulkner also made the point that there were buildings and spaces in Yoknapatawpha which, if not "gender specific," were at least accepted as male or female domains, the transgression of which had important symbolic connotations of self-assured determination (Figs. 21-26). The librarian entered the farmer's supply store where Jason IV had started as a clerk and where he now owned his own business as a buyer of and dealer in cotton—striding on through that gloomy cavern which only men ever entered—a cavern cluttered and walled and stalagmite-hung with plows and discs and loops of tracechain and singletrees and mulecollars and sidemeat and cheap shoes and horse linament and flour and molasses . . . and strode on back to Jason's particular domain in the rear, a railed enclosure

cluttered with shelves and pigeonholes bearing spiked dust-and-lint-gathering gin receipts and ledgers and cotton samples and rank with the blended smell of cheese and kerosene and harness oil and the tremendous iron stove against which chewed tobacco had been spat for almost a hundred years, and up to the long high sloping counter behind which Jason stood .[11]

The folk houses and country stores were similar to the larger, if equally primitive, barns, cotton gins, churches, warehouses (Figs. 27 and 28), and train stations (Figs. 29-31, 33) of Yoknapatawpha. Unlike the elegant Beaux-Arts terminals in Memphis, Jackson, and even Holly Springs, the simple, utilitarian small-town train stations in Oxford, Ripley, Como, and Batesville were particularly prominent in Faulkner's world. The depot in Oxford (Fig. 29) was a lively nexus of comings and goings for townsmen and University students alike. Especially at the nearby coffee house, "The Shack," which overlooked the station, Faulkner joined fellow students in lively socializing. From the same station in Yoknapatawpha, Quentin Compson departed for Harvard, and countless Jeffersonians entrained for Memphis, New Orleans, and exotic points beyond. More ominously, from the same station in Jefferson, Temple Drake, in Sanctuary , began her perilous journey, which darkened even more precipitously as she abandoned the train a few miles south in the station at Taylor.

Compared to the high elegance of the neo-Gothic Episcopal Church in Jefferson, Dilsey's primitive church in The Sound and the Fury (Fig. 32) presented a palpably different image: The road rose again, to a scene like a painted backdrop. Notched into a cut of red clay crowned with oaks the road appeared to stop short off, like a cut ribbon. Beside it a weathered church lifted its crazy steeple like a painted church, and the whole scene was as fiat and without perspective as a painted cardboard set upon the ultimate edge of the fiat earth, against the windy sunlight of space and April and a midmorning filled with bells. Toward the church they thronged with slow sabbath deliberation . The interior had been decorated, with sparse flowers from kitchen gardens and hedgerows, and with streamers of coloured crepe paper. Above the pulpit hung a battered Christmas bell, the accordion sort that collapses. The pulpit was empty, though the choir was already in place, fanning themselves although it was not warm .[12]

Indeed, in Yoknapatawpha's folk, vernacular buildings, the actual and the apocryphal were remarkably consanguine.

Figure 20

Stores, Taylor, Mississippi (late nineteenth century).

Figure 21

Goodwin and Brown's Commissary, Courthouse Square,

southeast side, Oxford, Mississippi (1880s).

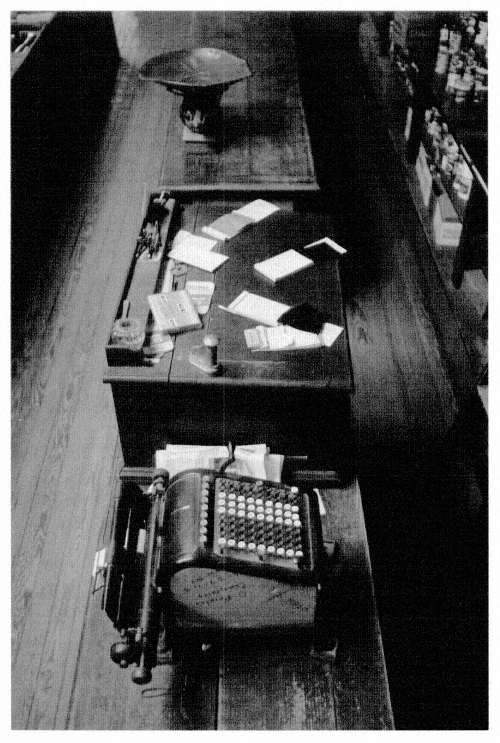

Figure 22

Counter, D. Pointer & Company, Como, Mississippi (late nineteenth century, demolished).

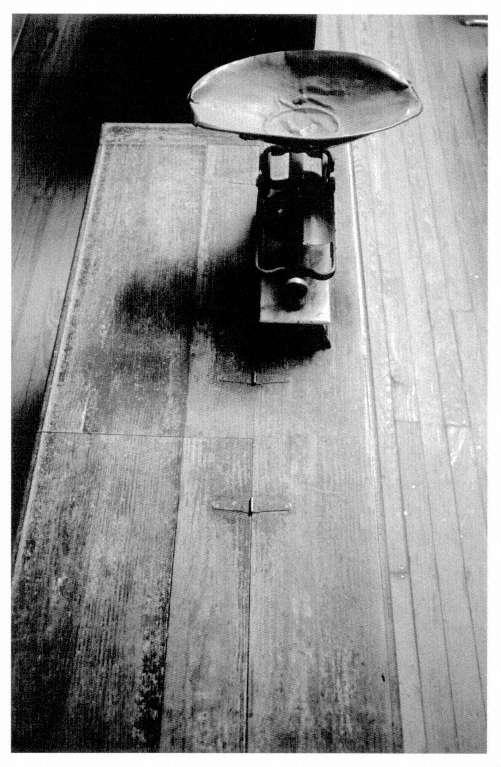

Figure 23

Scales, D. Pointer & Company.

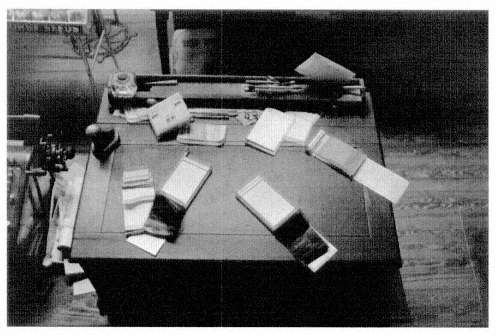

Figure 24

Desk, D. Pointer & Company.

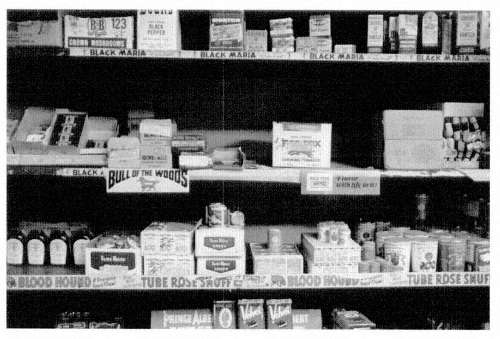

Figure 25

Snuff Shelf, D. Pointer & Company.

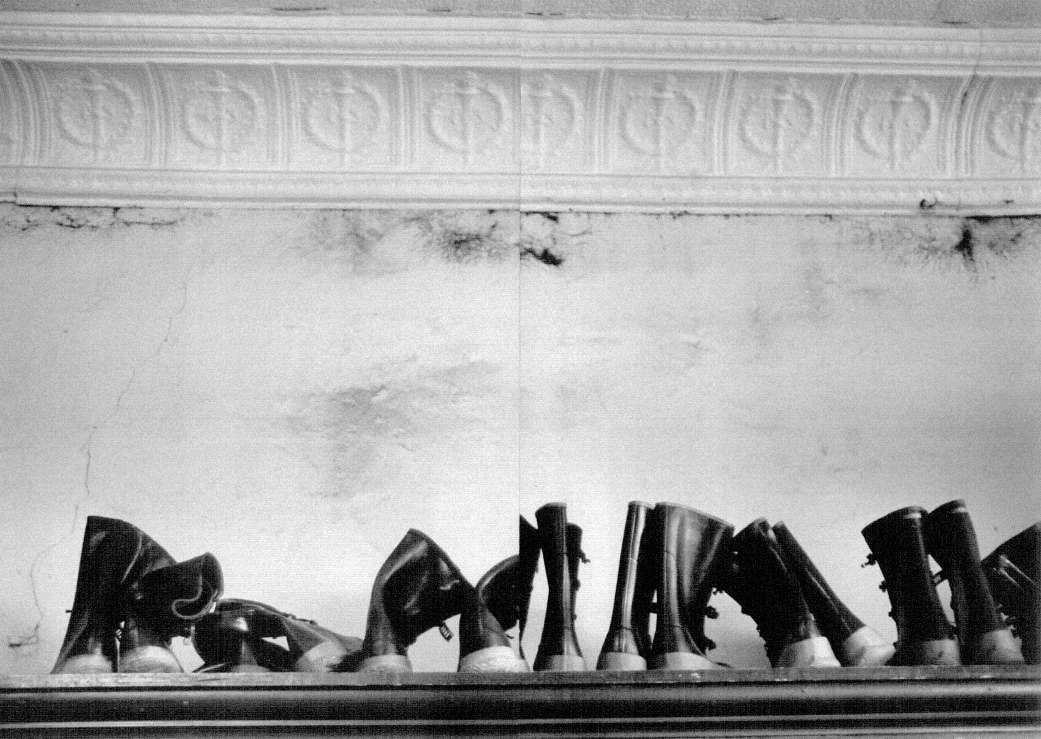

Figure 26

Shoes and Cornice, D. Pointer & Company.

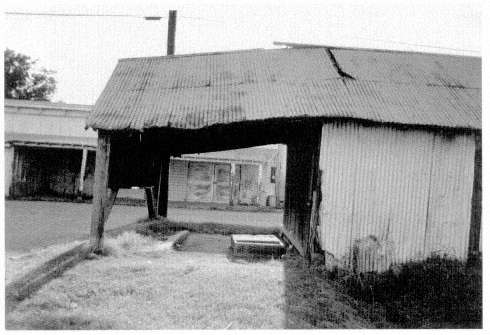

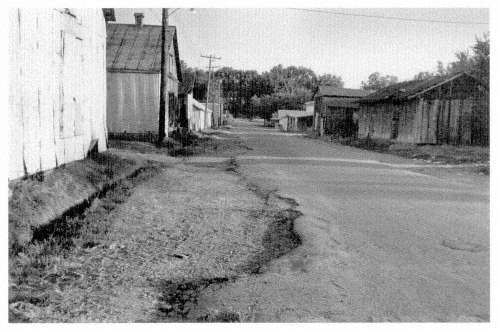

Figure 27

Warehouses, Back Street, Como, Mississippi (late nineteenth century).

Figure 28

Stores and Warehouses, Back street, Como, Mississippi (late nineteenth century).

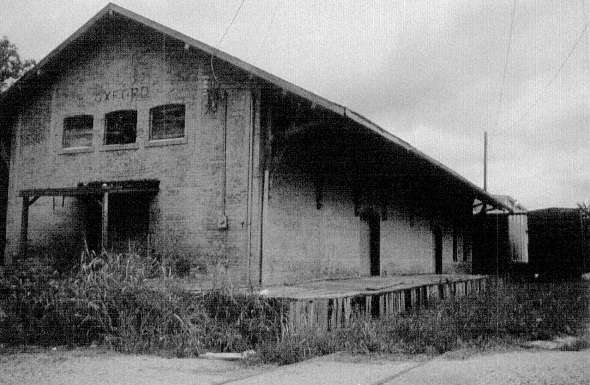

Figure 29

Train Station, Oxford, Mississippi (late nineteenth century).

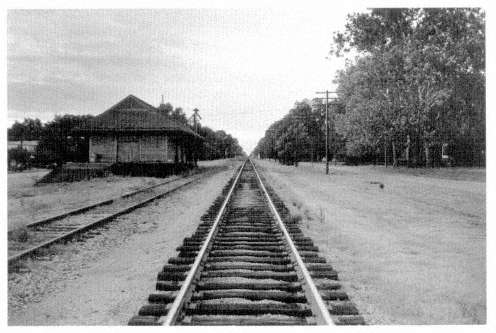

Figure 30

Train Station, Como, Mississippi (late nineteenth century, demolished).

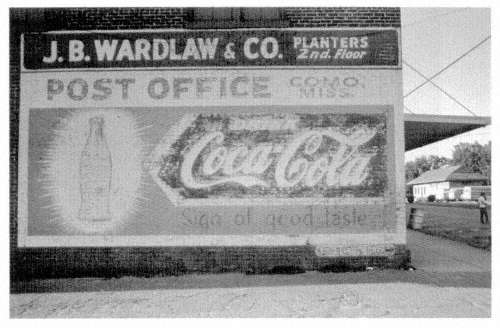

Figure 31

Train Station and Coca-Cola sign, Como, Mississippi.

Figure 32

Armstead Chapel, C.M.E Church, Oxford, Mississippi (mid-twentieth century).

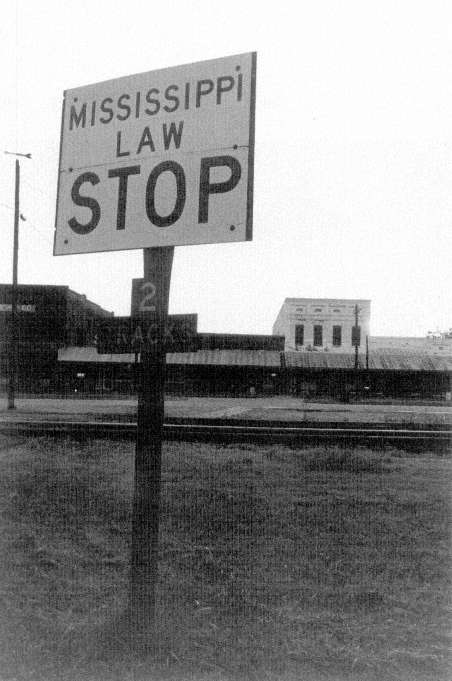

Figure 33

Stop Sign, Train Station, Como, Mississippi.