PART TWO—

PERSECUTION AND PERSISTENCE

Seven—

Family and Patronage: The Judeo-Converso Minority in Spain

Jaime Contreras

In 1983, Professor Heim Beinart, who has studied the crypto-Jewish community of Ciudad Real in great detail, called attention to the importance attached in that community to family ties and kinship relations. Searching for formulas to explain the cultural community which the Judaizing conversos of La Mancha had apparently established, Beinart concluded that endogamous matrimony was the essential cause behind the "manifestations of a common destiny"; manifestations which the entire cryptic community expressed openly with the violent eruption of the Tribunal of Faith in the final years of the fifteenth century."[1]

Indeed, it was Julio Caro Baroja who, thirty years ago, spoke of the need to elaborate a "cohesive and organic" history of the Spanish crypto-Jews from a more ethnohistoric perspective. Don Julio recommended that, for such an arduous task, it would be necessary to study "a couple of thousand Inquisition trials," which would eventually lead to the "history of a few hundred families united by a system of lineages." Caro Baroja thus defined a very precise operative method.[2]

As of today, neither the methodology proposed by Caro, nor the attention of H. Beinart, has elicited much enthusiasm among historians of the Hispanic crypto-Jews. It must be recognized that within specialized historiography, the judeoconverso families and their systems of lineage and kinship have hardly attracted much attention. Nonetheless, there is an obvious need to understand the mechanisms that develop within the limits imposed by blood ties, kinship, or relation through marriage. Today, our historiography demands this knowledge. To strike off on that barely intuited path, to delimit its contours, to specify its des-

tiny, and to draw up its outline, are the principal objectives we propose for ourselves as a team of investigators.

Our goal is, without a doubt, ambitious, because tackling the problems presented by the judeoconverso minority from a multidisciplinary perspective is a very involved and complicated procedure. Initially, we are obliged to study previous works in order to construct the first basic levels of study. Obviously, neither the original manuscripts, nor the printed sources, and certainly not the topic's enormous bibliography were conceived of or elaborated in terms of our own original focus. But whatever the methods of study, the questions posed were always similar in both structure and form from the very origins of the converso problem. All historical periods have dealt with the same protagonists, clothed at times in similar garb and at other times in contrasting dress. We are familiar with all the characters: they are the Old Christians and the New Christians; they are the Jews, the Judaizers and the "marranos"; they are also the Inquisition, the Crown, the Church, and the rabbinical authorities of the Jewish communities of the Iberian Diaspora.

The questions ordinarily posed by historians to these protagonists stem from the fact that two religious communities existed—the one a majority and the other a minority—who lived out their relationships in an especially dramatic manner. This much is true, but the issue of the degree to which the members of one community identified themselves vis-à-vis the members of the other, and the degree to which orthodoxy defined itself as such in an antinomian relationship with heresy has produced an inevitably simplistic and excessively rigid methodological framework.

Religious overtones shaded questions formulated from the two sides. Did marranismo exist as a religious phenomenon, or, to the contrary, was it "invented" by the inquisitors? What is the significance of the term Judaizer? Did all the New Christians Judaize? These questions were posed repeatedly, and always from either side of the problem. Not surprisingly, the answers were also inevitably polemical, and always elicited rich and subtle interpretations.

As a result, the issue, always complex and always unfinished, has remained, in my judgment, without precise horizons. Inordinate and at times intentional attempts to establish one sole perspective as a means of targeting and understanding the problem have blocked other interpretations. In this case, the historian must understand his own limitations. Is it possible to render comprehensible and objective a phenomenon which, because of its nature, resists focus?[3] Secrecy and clandestinity, both inherent aspects of crypto-Jewish sociology, complicate

any attempt to understand its nature. The cryptic nature of the Judaizing communities was concomitant with the unstable grounding of their very existence. Heretics in the eyes of the Catholic majority, they also experienced extreme difficulties in being acknowledged as Jews by the Hebrew communities abroad. This lack of adaptation to either system created a constant and permanent tension in the daily existence of the cryptic community; there was no alternative but to accept the situation and to make of it a customary form of internal coexistence. Nevertheless, and in spite of the relative guarantee of institutional security, this state of constant anxiety inevitably generated multiple responses from both individuals and groups. Both the actual situations and the social rejection that caused them resulted in a voluminous documentation from both the Catholic authorities and their Jewish counterparts which, while extremely interesting, is profoundly biased as well. The conversos who Judaized did not bequeath to posterity their own testimony; on the contrary, they were obliged to accept the fact that this task would be undertaken by others: at times, by their bitterest enemies, the inquisitors, and at others, by the Jews of the Diaspora, who frequently demonstrated a manifest unwillingness to integrate them into their communities.

As a result of all this, it is an incontrovertible fact that many historians, of whatever leaning, have found themselves unfailingly "trapped" by the seduction of the documents they have studied, documents not necessarily objective. Partly because of the documental bias and mainly because of the unilateral methodology applied, historiography on Iberian marranismo has turned out to be oversimplified and dualistic. There are two principal positions: (1) that marranismo is clandestine Judaism and (2) that marranismo existed only in the minds of the inquisitors and those who supported them.

These two entrenched conclusions have made it difficult to distinguish the diverse variations existing between one position and the other. More relativized positions need to be adopted: neither do all the trials begun by the Holy Office convey the image of a conscious and orthodox Judaism, nor can we assume from the rabbinical response that many conversos did not wish to Judaize. Liturgical obligations or traditional religious observances do not in themselves define the religion of the marranos. We are not in the presence of a religious creed that conforms to fixed or stable concepts. Clandestinity and secrecy reduced the religious socialization and allowed for a varied religious individuality; the trials of the Holy Office provide an extensive collection of examples in this regard.

Consequently, marranismo resulted less in a ritualistic and observant

practice than in a consciously motivated integration within Mosaic law,[4] undertaken individually or socially. There are many paths that lead to such a level of consciousness, but the ethnic bonds of a community are the first basic step toward initiating the process of social and religious integration. In other words, the term so commonly used in the documents of the times defining the converso ethnically as a "New Christian of Jewish origin" is merely the starting point. From this there developed a more or less singular religious practice—crypto-Jewish religiosity—which, under favorable circumstances, may have culminated in the complete acceptance of actual Judaism. This usually occurred when the individual, having to flee from the Iberian peninsula, arrived at a Jewish community in one of the other European countries.

This process may explain the existence of the cryptic communities of Iberian marranismo and their logical migratory patterns toward the diverse Jewish communities of Europe.[5] This produces, in turn, a "natural" evolution that begins with the New Christian and concludes with the Jew; the marrano is the intermediary stage.[6] There do not appear to be many doubts in this respect. Therefore, ethnic issues were mainly responsible for social segregation and juridical-administrative differentiation. To be marginalized in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Spain, it was not necessary to have been tried as a Judaizer by the Tribunal of Faith; all that was necessary was to have a few drops of Hebrew blood. Only by concealing the presence of these drops could the individual begin to aspire to an accepted social status that conferred both respect and honor. A vast amount has been written on these issues,[7] and it also has been pointed out quite clearly that money could expunge dubious ancestry and create ancient and time-honored lineages. Through these means, one purchased the required reputation; yet one error, one small, barely perceptible but intentional indiscretion was sufficient to destroy the entire achievement. When this occurred, the affected individual suffered immediate exclusion. While such a thing rarely happened, the important fact is that it did happen, and this revealed the extent to which lineage, belonging to a clan line, and ethnic origin were the central issues in the drama of coexistence between the majority and the minority. Race and lineage, both separately and barely differentiated from each other, represented the primary characteristics of social exclusion.[8]

The statutes on purity of blood, that neurotic obsession to "stir up entombed bones," as Quevedo wrote,[9] functioned as a means of attacking the social and juridical rights of the New Christians, but what is particularly interesting is that they also made more selective the social mechanisms that led to marriage. The "quality of the blood" was trans-

mitted through lineage and could be purchased with money; yet, like wine that must age with time, only marriage guaranteed it. For this reason the politics of marriage were of vital importance.

The letters patent of nobility and the certificates of purity, results of tedious and complex secret investigations, were superimposed onto the inexorable and selective economic process and provoked a sharply defined and strengthened reaffirmation of the traditional social groups and estates. The social expansion timidly carried out in the first forty years of the sixteenth century was aborted after the generalization of the statutes. Lineages were once more reaffirmed, family ranks closed ever more tightly among themselves, and clans and kinships were consolidated. Very few possibilities remained for persons of questionable background who had not succeeded in establishing themselves within respected and highly regarded lineages.

If, as we know, the Edicts of Faith published by the Holy Office occasionally served as propaganda through which many crypto-Jews, heretofore ignorant of the religion they wished to practice, reaffirmed their faith,[10] the statutes also allowed many New Christians, isolated within the vast expanse of the majority, to discover their unique identity. It was obviously a cultural identity that consequently reinforced the bonds defining them—both social bonds and ethnic ties.[11]

In examining the wide range of implications which these premises suggest, my principal objective is to unravel the complex familial structures developed internally within the ever unstable cryptic communities; such an objective demands as well that we focus carefully on the relations between these judeoconverso groups and the surrounding environment, that is, the Old Christian majority.

We must therefore adopt a rigorously selective criterion with regard to the "diverse messages" transmitted by the documentation of the period. As is well known, the documentation of the time exhibits a virulent anti-Semitism, sometimes latent and at other times quite explicit. The image presented in this vast quantity of paper is stereotypical, but no less real for this reason. The Judaizer is a permanent protagonist in daily reality. His presence is constant—always necessary but always uncomfortable. He embodies adverse stereotypes; he is the typified enemy, the opposing archetype who permits self-affirmation by means of negation. The Judaizer is the expiatory victim, the most hated antisocial agent because he is the heretic par excellence and, affirming the magic aspect of collective existence, he is the cause of all the evils that afflict the realm.

The image, most definitely stereotypical, that emerges from these

mountains of books, documents, and treatises reveals a rarefied cultural atmosphere that logically corresponds to the collective parameters of the Catholic majority. Constant references to this stereotype have slowly formed a strategy of exclusion silencing all divergent manifestations. Uniformity has been imposed and thought has become monolithic.

The polemic over the statutes of purity, described in meticulous and detailed form by Albert A. Sicroff, exemplifies the inexorable tendency to suppress all differences. Sicroff demonstrates how certain positions that emerged triumphant at the end of the process had been very weak at the start. The supporters of the statutes increased in number over time, suggesting the existence of two "periods" of diverse evolution, at the end of which social coexistence fossilized. The various options were polarized into two essential positions: the dominant groups and the excluded ones. The former defined themselves through racial purity, noble lineage, virtuous reputation, and orthodox religion. Wealth was also an attribute. The excluded groups, in contrast, were so defined by the absence of all of these factors.[12]

There were many New Christians, crypto-Jews who accepted their marginalized condition and used it to cement their identities; they viewed their isolation as the feature that most defined them. Thus, in the face of religious persecution, they reconfirmed their desire to Judaize; in the face of social rejection, they reaffirmed their clandestine relations; in the face of the contempt and political neglect of their king, they collaborated with his enemies;[13] and finally, in the face of the baroque exaltation of "the lineage of the peasants," they defined a premeditated familial strategy, distinctly endogamous, as an essential means of ensuring the survival of their ethnic lineage.

Obviously, we cannot deduce a monolithic uniformity in either social structure, belief, or behavior. The attitudes learned in the bosom of the community, as well as those acquired in the contacts with foreign synagogues (aljamas ), blended with difficulty within the limited and asphyxiating boundaries of clandestinity. There, the pressure from the majority was felt as an oppressive burden. It was not easy to resist, and on many occasions the weakness of the cryptic system was unable to withstand it. It was therefore necessary to maintain, among individual tendencies and general requirements, a certain degree of laxity that would guarantee coexistence, minimizing the risk of flight and the profound estrangement which, tragically and irreversibly, resulted in the Holy Office.

Of all the elements that assured the cohesion of the cryptic group, two stand out: the unity of faith and the solidarity of blood ties. Américo

Castro, with remarkable intuition, discovered the enormous importance that the Hebrew community of the Hispanic kingdoms gave to the issue of "blood." When Castro studied the emergence of the statutes, he saw in them the triumph of the Christian "caste" over the Hebrew "caste," a triumph based precisely on a particularly Jewish characteristic: the interest in maintaining at all costs their own specific singularity. Castro's thesis, bold and original, provoked angry and, at times, bitter reactions. This is not the occasion to repeat past dissensions that can only be understood within their social and intellectual context; yet today, when many historians, whether they are Jewish or not, investigate these themes, they arrive at hypotheses quite similar to those formulated earlier by Américo Castro. The topic of blood and lineage is one of these overworked themes.

The Hebrews, argued don Américo, boasted of possessing pure and ancient blood; they thus displayed pride in having an ancestry at least as long and ancient as that of the Old Christians. They considered themselves descendants of a superior ancestry that conferred attributes of nobility upon them. In their theories, the Hebrew minority followed the same arguments as the Old Christians. They explained, for example, that the exaltation of blood and lineage was not, in and of itself, strictly a racist formulation. This was not a mechanistically physiological or biological racism but rather the nourishing of a collective sentiment that inherits the consciousness of a past tradition, culture, and collective family. In the same way that they operated for the Old Christians, the laws of heredity—biological laws—did not alone transmit the blessing of a Jewish ancestry; moral and cultural values acquired in the mythical and courageous past were what determined the quality of blood. Lineage was the end of this process. Lesser nobility, nobility, and purity of blood formed the essential triumvirate of the Iberian Jews' social ethic, which they defended with the same energy as the Christian apologists: "Do not try to shame me by calling my parents Hebrews. Certainly that is what they are, and I desire it so: if near-antiquity is nobility, then who is more ancient?" Alonso de Cartagena eloquently defended his Hebrew ancestry.[14]

The antiquity of those mythical lineages lost in the past was what transmitted the honor, respect, and reputation which the Old Christians claimed exclusively for themselves. The Iberian Jews and New Christians developed an imitative strategy as anti-Semitism was unleashed and, encouraged by popular hatred, the justice system, with its Christian bias, penetrated the synagogues. The contempt of the masses extended everywhere, the Jews' protectors lost power, and the Crown acceded to

the cries for extermination. During those years of violence, Jewish Spain and the newly converted proudly exhibited the antiquity of their lineages. This was a tardily awakened consciousness, since the ghetto had already been formed and its violent siege presaged terrible fatalities. That "historical" consciousness which rejected exclusion was deeply resented by the Christian majority. The palace priest exemplifies this attitude: "They [the Jews] pretended to supreme excellence, presuming that in the entire world there were no better people, neither more discreet nor more respected than they, being of the lineage of the tribes of Israel."[15]

The lineages of Israel, therefore, were ancient. Nobility, virtue, and pure and respected blood: these were the parameters Castro considered fundamental to the Hispanic Hebrews. They are not, in principle, new arguments, but nevertheless it is interesting to see how other historians, with another focus and different documentation, have emphasized the same themes that obsessed Castro.

A recent study by Swetschinski on the Jewish communities of Amsterdam during the seventeenth century stresses the social differentiation of the Sephardic Jews as compared with the Ashkenazi branch. In the city of Amstel, the Jews who had emigrated from the Iberian peninsula acted as if they were superior to natives of other areas. Swetschinski, studying the apologetic writings of the founders of the "Portuguese" community, notes the constantly brandished argument: "the superiority of the Hebrews originally from Sefarad."[16] Mosés Aron ha Leví, chronicler of the recently established community, argued that the Iberian Jews who settled in Amsterdam had brought with them the ancestry of their blazoned lineages. Daniel Levi de Barrios, the most prolific of all the Jewish writers who wrote in Castilian in Amsterdam, referring to the origin of his brothers, could not find more authoritative terms than "purity of blood" and "superior lineage." Daniel Levi de Barrios was so "Hispanicized" that Scholberg, his principal scholar, generalizes that "the Sephardic Jews of Amsterdam seem very Spanish in this respect."[17]

Thus, the bourgeois and "tolerant" Amsterdam of the mid-seventeenth century hosted a Jewish community of Iberian origin which, having fled from the Holy Office, was as much obsessed with lineage as were the Old Christians. This obsession was their governing feature and was what distinguished them most clearly from Jews who were emigrants from other areas. Escaping from a closed and secret situation, those Jews who in former days had survived the persecution of the Tribunal of Faith knew better than anyone else that only through blood alliances could they preserve their religious beliefs.

In this as in many other issues, Revah, when studying the "Bocarro-Francés" Jewish clan, understood the interests of family ties and, consequently, the singular importance of marriage for the community.[18] It was therefore essential to employ the appropriate strategy. Only those unions which faced the future with the weight and the duty—ultimately, the heritage—of the past could sustain the magic of the lineage, and with it, tradition, honor, and esteem.

Here we have the Jewish family or the Judaizing family constituting itself as a basic element of social and cultural cohesion. The classical endogamy of the Judeo-Christians was ultimately necessary, because it alone allowed religious affirmation, facilitated the process of socialization, and also assured the reproduction and subsequent development of economic structures. The judeoconverso family thus fulfilled three principal functions: it ensured faith, preserved the entity of lineage, and made possible the attainment of wealth.

Historians of the conversos have scarcely questioned this triple familial function. In this regard, the partial and myopic vision of the historian has portrayed a false and incomplete image of the conversos. We do not know them as forming part of a social group, or within their familial organization, or as participating in their own specific cultural world; nor do we know them, with rare exceptions, as individuals, persons in and of themselves. Our knowledge is limited to an image conveyed by the literature of the period and the documents of the Holy Office, and that image is particularly biased. In the inquisitorial documents, their predominant role is that of victims, and they are recognized as such in the formal and often tragic language of the penal trials. We have rarely sought any meanings beyond this image; we must therefore find and decipher the documents. Histories of the family, lineages, and kinships are, in themselves, suggestive and novel vantage points which the historian cannot ignore.

Caro Baroja has shown us this path. As indicated above, he believed it necessary to write the history of those "hundreds of lineages." But when striking off on that path, we discover that the methodology is unknown to us and that our lack of precision forcefully limits our steps.

Nevertheless, as we know, research on the history of the family has increased since the decade of the 1960s. This growth is due to the qualitative evolution occurring in historical demographic studies.[19] Through the analysis and the quantification of natural factors of population, this discipline has shifted toward the study of the social aspects that develop around the family structure such as types of marriages, transmission of belongings, access to property, and localization and analysis of pa-

tronage. The history of the family is thus an immense field where the interdisciplinary nature of the social sciences may well demonstrate its effectiveness. Whatever the future directions may be, some thoughts have already been firmly established: the family is the key institution sustaining the social system, and this occurs through two opposing yet complementary functions: on the one hand, the transmission of sociocultural values through the biological laws of heredity, and on the other hand, the "control" of any dysfunctional element that might arise within the family.[20] In summary, contemporary cultural anthropology reminds us that the family in the Habsburg period reproduces itself, thus making "commercial strategies" possible, regulating the relations among its members, and perpetuating the force of authority by sacralizing its effects.

Nonetheless, such conclusions result from theoretical speculation, since concrete empirical analysis as applied to past eras is in the initial stages. Moreover, the scarcity of this type of research on minority groups is overwhelming. With such a limited background, to investigate the systems of familial organization of an ethnoreligious minority that also lives cryptically and whose real existence is not legally recognized by the majority implies an effort that remains to be carried out in all its aspects.[21]

The history of the crypto-Jewish family must be patiently reconstructed. Such an objective requires an initial premise on the part of the investigator: in the crypto-Jewish community, the family was always a component of internal solidarity. Let us begin, then, at the beginning.

During the fifteenth century, when the intensity of the conversion process paralleled institutional violence, the converts from Judaism, the New Christians, developed an entire strategy in order to reach the highest levels of the urban aristocracy. Thirty years ago, Francisco Márquez Villanueva explained that the objective was to control many municipal offices.[22]

Essential and complementary elements intervene in that historical process of social and political ascent; one is the economic level attained and the other, the bonds of solidarity woven by family and lineage. The second element is conditional upon the first, as the essential means that assured the marginalized minority's economic success was the harmonious, supportive, and operative inclusion of the individual within the family clan. Only when this had been accomplished could the individual ascend socially and politically, obtaining municipal offices, positions that ensured a certain immunity. This was surely the social direction of the

recently converted minority, whose specific marginality halfway between the two religions gravely endangered their existence as a group.

The propensity toward sociopolitical ascent originating in familial solidarity does not suggest a behavior unique to the crypto-Jews, but their only possible strategy. The dominant sociopolitical system was based not upon the individual but rather upon the larger kinship system. Today, it is obvious to everyone that the group's definitive component was to be found in the hierarchical relations of loyalty, and that such loyalty, a primary characteristic of private family relationships, constituted the fundamental public feature of political relationships as well. For this reason there was no possibility of promotion or of any kind of social recognition not based a priori in these primary structures. The converso, like any other individual, ascended socially and politically through channels attained by the clan and the "family" to which he belonged. The political importance of groups as defined by blood and lineage tainted public life with a sordid and, on occasion, unabashed struggle for higher levels of power. The conversos were not strangers to such conflicts. Márquez Villanueva writes very lucidly on this point: "The clan spirit of the converso cliques impelled the ascent, in the face of all opposition, of their diverse members through tactics as efficacious as they were rancorous and, in the long run, prejudicial against those who employed them."[23]

The "clan spirit" dominated political relations, and all pertinent obligations were derived from it. Given that the attained occupation or post was not an individual achievement but rather a triumph in which the clan played the main role, this same clan could also impose its own internal needs, the two most important being the "cession" by the individual of the office to a third party and the establishment of new ties or obligations of patronage. The degree of kinship relations was a well-known leverage, in the cession of sinecures or municipal offices and in the persistent interest in seeking the "protection" of a powerful house.[24]

Let us summarize: blood ties and kinship bonds, whatever their extent and degree of intensity, wove a tight network of interests and solidarities throughout Iberian society with hardly any individual exceptions. Such were the basic principles of social structures. The conversos followed the same system as the majority group, but their circumstances obliged them to reinforce it. The mere fact of belonging to an ethnic minority was in itself a segregating factor, aggravated besides by harsh religious repression; all of this thrust the conversos to the margins of the system. Internal cohesion thus became the sole essential condition for survival. At

the end of the fifteenth century, when the recently created Inquisition penetrated straight to the heart of the cryptic communities, they had still not found a better solution in their defense than to practice a closed endogamy. Mixed marriages (between Judaizing conversos and Old Christians) were not very frequent, and although there were exceptions, nuptials within the Judaizing group were always the norm.

This endogamous practice established networks of solidarity among most members of a community, and, by extension, it created connections with other small local communities to the point where, at the end of the fifteenth century, almost all communities were affected. The constant references to relatives and friends which abound in the procedural documents of the Holy Office indicate the extent to which the bonds of solidarity were extended far beyond the more precise limits of blood ties. Ethnic ties, family connections, and religious fellowship formed the defenses that guaranteed survival. Heim Beinart discovered a similar situation in Ciudad Real around 1480, which he describes in these terms: "At the end of two or three generations, [the conversos of Ciudad Real] had become one big family whose members were as powerful as ever."[25]

Obviously, a system structured in such a way could not be perfect. Its coherence was not totally guaranteed because it ultimately depended upon the degree of individual and social adhesion. Blind loyalty could not be counted upon, and the existing adhesions are explained by the subtle results and the dialectical play that were developed internally in consequence of the group's needs, expectations, and gratifications. The complexity of these relationships inevitably created frustrations—implicit or explicit—affecting either the individual or the group and constituting the breaches through which the repressive mechanisms of the majority were able to penetrate the interior of the community. The principal mission of the cryptic authorities was to prevent this from happening, giving warning and appealing urgently and anxiously to the community's internal solidarity. Their principal task was to avert the destructive effect of the talebearer. The Judaizers of many small communities had already experienced the devastating consequences brought about by the tribunal. The same thing always took place: the inquisitors penetrated through the breaches left open by private dissatisfactions. When this misfortune occurred, solidarity, which had been attained with such difficulty, was destroyed.[26]

The danger of intrusion was difficult to avoid given the constant fear one lived in: "They always live uneasily and in fear of the harsh Inquisition," wrote Levi de Barrios.[27] Even during the periods of minor repression, security was not guaranteed. Clandestinity and secrecy imposed a

tense and harsh way of life. The crypto-Jew not only had to protect himself from the "raids" of the tribunal but was also severely censured by many former compatriots who, now safely practicing Judaism in some foreign community, bitterly criticized the crypto-Jew's reluctance to flee, as they themselves had, in search of a safe port. Abandoning home and business, they had fled from idolatry in order to live the religious tenets of their faith.[28] The effects of their criticism on the crypto-Jew were thus very important, given the moral authority that such criticism wielded.

It was difficult to live in a state of permanent internal exile; the need to leave the ghetto and participate in some way in the public arena was urgently felt, even when it entailed adopting a false identity. While dangerous, crossing into the hostile exterior of the majority could also alleviate the seriously conflictive tensions that accumulated within the interior. Permanently forced to live a double life, the cryptic community paid dearly for its inherently deficient structure. A progressive loss of cultural patrimony, an increasing weakening of religious devotion,[29] and also the overwhelming presence of the majority weighing down forcefully upon any minority cultural spirit were to blame for the grave deterioration which the community inevitably suffered.[30]

It was necessary to counteract these deficiencies through compensatory means, which were not only helpful to the individual but provided bonds of solidarity for the group. One of these means was the economic influence held by the community as a whole, especially during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

We should, however, first consider some specific issues regarding the Jew's so-called aptitude for accumulating wealth. Like all generalizations, this is a simplistic distortion of historical reality. It is no longer possible to maintain that economic prosperity prevailed in all the Judaizing communities on the peninsula; examples proving the opposite abound everywhere, in Iberia as elsewhere. Need it be stated that neither the Jews nor the conversos constitute, in themselves, a specific social group in the production of capital of the period? One can easily demonstrate the presence of Hebrew blood, Jewish or converted, on each and every one of the rungs of the social ladder. Wealth is not a patrimony derived from ethnicity or beliefs. To affirm the opposite is to assume as true the classic typical anti-Semitic argument which endeavors to make a totality out of what can be no more than a partial reflection of reality. The strategy of stereotyping,[31] as we already know, consists of assimilating a partial reality (some conversos were wealthy) into a fictitious totality (all conversos were wealthy).

By affirming these basic principles, the historian does not obscure

reality: a minority of judeoconversos had amassed substantial patrimonies and risen to the highest levels of social prestige. Jewish men played crucial roles in the world of commerce, in business, and in government.[32] Although their participation in such activities assumes far more importance if we compare it with their numerical insignificance, it is also true that their contemporaries' view of this problem was biased, because of the perpetually distorting effects of official propaganda. But when it was said, for example, that "the pulse of commerce is sustained only by the merchants of the Hebrew caste,"[33] we should understand that such a judgment, while not totally accurate, did not convey a completely distorted image of reality. The so-called "businessmen" of the seventeenth century were made up of a contained group of wealthy conversos principally in Portugal.

The people were not too misguided when, humiliated by their poverty, they observed, in contrast, how wealth overflowed the homes of some New Christians. While it would be absurd to deny this fact, it has not been possible to measure its entire extent and significance, nor is this the moment to do so.

Nonetheless, we must ask what the reasons were for this acknowledged economic success. There is no single or direct answer, but an objective reading of Inquisition documents discloses several basic causes, one of which is the organic solidity of the kinship ties. This relation was pointed out above, as was the fact that even though research is scarce, some has been carried out.

In his study of the Bocarro-Francés family,[34] Revah furnished proof of the connections between its kinship ties and the commercial enterprises the family sustained. This is not the only example; in his investigation of the Sephardic communities of Hamburg and Altona, Kellembez[35] patiently worked out the complex networks of commercial contracts uniting them among themselves and with the conversos from the interior of the Iberian peninsula. This splendid work outlines a complex variety of commercial formulas structured and guided by the imperatives of kinship. Kellembez demonstrated with precise genealogical data that these well-known commercial ventures, expanded across oceans and characterizing the rise of early capitalism in the seventeenth century, were built upon the permanence of blood and kinship through marriage. Located throughout the commercial routes that linked other continents to Europe, many Jewish families maintained permanent commercial ties made possible only through kinship or affinity.

New Christians from Portugal and Castilian crypto-Jews who traded wool, for example, maintained close relations that merged together fam-

ily and business. The Judaizing conversos of the interior and Jews who had fled to the exterior organized commercial societies that at times extended to the coastal boundaries under family protection. Neither dispersion nor distance presented any kind of obstacle to families and businesses; on the contrary, the strength of the blood ties conferred fundamental advantages on such risky ventures.[36]

Commerce, whether domestic or destined for the great overseas routes, was the speculative activity par excellence. The most prosperous fortunes were based not on production, but on trade. The secret of a successful business lay in knowing how to exploit the price differential which a particular commodity could generate on its round through diverse markets. The merchant in charge of buying or selling required specialized agents, located in each and every one of the markets on the circuit. He needed to gain the trust of these agents. For this reason, the most suitable partner or employee either was a relative or belonged to the same lineage. Commerce functioned through strong ties of internal solidarity, and such "securities" constituted an essential condition for its development. This is not very difficult to document; we need only list the great fortunes originating in the Portuguese community of Amsterdam. The commercial emporia of Abraham Pereira, of Duarte Fernández, and of Jerónimo Nunes da Costa reveal a hierarchical family organization, with each member of the family assigned a specific task.

Let us summarize: there is no doubt that the history of the crypto-Jews of the Iberian peninsula demands new approaches in order to reveal the fundamental components of the life of this minority interiorized by their own clandestinity. We need to ask how cryptic families functioned. Yet this is only part of the problem. It would be too simplistic to convey the impression of a strong, solid, socially and culturally cohesive minority deriving those characteristics solely from its secret religion, without mentioning that, together with its integrating tendencies, the minority also experienced disintegrative factors and opposing tendencies.

If the study of the interiority of the crypto-Jews is suggestive and attractive, their external profile, their social life, is as much if not more so. In public the judeoconverso was an ordinary sort with no distinguishing characteristics. Like any other individual, he formed part of the complex mesh of social relations; he acted within the framework of duties and privileges inherent in a hierarchical society. He also shared in the consciousness that defined, socially, economically, and ideologically, the social group to which he belonged. The judeoconverso, upon leaving the "ghetto," could not avoid entering the corporate structures that

regulated everyday life. He belonged to guilds and confraternities and participated as well in the factions so frequent at the time. In each and every one of these, the importance of dual loyalty systems (bonds between two people which provide protection and benefit) took precedence over every other form of horizontal relationship. This primary system functioned throughout the entire social pyramid, weaving dense social networks, made hierarchical and vertical according to a set of rights and obligations that were unwritten but were always effective. The society as a whole was formed by a complex graded network of dual relationships that ascended to the apex of the pyramid, the position held by the nobility, the great protector and recipient of diverse loyalties.[37]

The patronage system thus defines relations of dependence whose essential cohesive elements are kinship and lineage. The crypto-Jew was no exception to the "patron-client" relationship. When, from the secret recess of his private life, the Judaizer went out into the world, he did so in obeisance to his noble patron and, like so many others, expected his protection in return. Whatever vantage point on the social pyramid we assume, the spectacle of a society "under patronage" is the same. The judeoconverso behaved the same way as any other individual. At court they depended upon this or that patron; Rodrigo Méndez Silva, for example, belonged to the Cortizo clan, which was very close to the Conde-Duque de Olivares.[38] The great physician and philosopher who fled from the Venetian ghetto, Fernando Cardoso, found himself "protected" by another illustrious Spanish personage: don Juan Alonso Enríquez de Cabrera, duke of Medina de Rioseco and admiral of Castile.[39] These are two examples of very well-known people, but there are many other unknown participants in the same system. To learn about these social mechanisms and to study the intricate network of interests is, ultimately, our essential objective.

Eight—

The Jew As Witch: Displaced Aggression and the Myth of the Santo Niño de La Guardia

Stephen Haliczer

From the perspective of the social historian, one of the greatest successes achieved by Habsburg Spain was its ability to avoid, in large measure, the massive witch-hunts that swept over most of the rest of Christian Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Historians have generally ascribed to the Inquisition much of the credit for this achievement. As a highly respected institution with well-established jurisdiction over matters of heresy or other threats to the Catholic faith, the Inquisition was in a position to set the tone for the entire Spanish legal system regarding such offenses. Although the Holy Office never attained complete control over crimes involving witchcraft, its skeptical attitude toward much of the evidence produced in these trials, and its well-advertised role in ending the Navarre witch panic of 1609–1612 profoundly influenced the entire climate of public and learned opinion in ways that tended to discourage witch-hunting on a massive scale.

In most respects, however, early modern Spain was little different from other contemporary societies since it housed the same kind and degree of social and economic pressures that engendered witchcraft accusations elsewhere. Spain shared with other countries, for example, the stereotypical image of women as being morally and intellectually weaker than men and, as a result, more likely to be vulnerable to the temptations of the Devil.[1] Moreover, apart from the reassurance in matters of religion offered by the fact of the Inquisition's existence, early modern Spaniards experienced the same anxieties and insecurities as their contemporaries in France or Germany and were, therefore, equally concerned about the threat from supernatural forces to their everyday life.

For its part, the Inquisition's attitude toward witchcraft accusations can hardly be attributed to any enlightened rationalist negation of the power of the Devil. As late as 1631, seventeen years after Alonso de Salazar Frías's celebrated Seventh Report to the Inquisitor General, Gaspar Navarro published his Tribunal de la supersticion ladina, in which he explicitly accepted the reality of diabolical pacts, maleficia and the witch's sabbath and called for exemplary punishment of witches. The work frequently quoted from the famous Malleus Maleficarum in support of its arguments and carried with it the warm endorsement of Dr. Baltasar de Cisneros, inquisitorial cualificador of the Zaragoza tribunal.[2]

The Spanish rulers of the period were themselves haunted by the threat of foreign aggression and internal subversion, an atmosphere hardly conducive to calm in the face of the witch craze. One of these rulers, Charles II, was himself the reputed victim of witchcraft perpetrated by the royal confessor Froilán Díaz. In the Franche-Comté, Luxembourg, and other parts of the Spanish Netherlands, the governments of Philip II, III, and IV strongly encouraged the persecution of witches and in Luxembourg alone there were 355 executions between 1606 and 1650.[3]

Given the fact that the Inquisition never had complete control over these cases, its increasing concern for the niceties of legal procedure alone could hardly have prevented a witch craze. Indeed this is amply demonstrated by the situation in Navarre in 1610–1612 where local justices aided by certain parish priests carried out the initial arrests, tortured suspects unmercifully, and extorted confessions which were then eagerly and uncritically accepted by the inquisitors on the spot.[4]

Under sixteenth- and seventeenth-century social conditions, therefore, the only thing that could account for Spain's relative inactivity in the face of the European witch craze was the presence in that country of another target of displaced aggression, a target so firmly identified in the public mind with all that was evil and pernicious that it could readily substitute for the witch as the ultimate source of social evil.

During the fourteenth century, with the breakdown of the old toleration that had permitted Christian, Jew, and Moslem to live side by side in relative harmony, the Jew became more and more identified as the chief enemy of Christianity. By the time of the Cortes of Toro in 1371, the Jews were described as "rash and evil men, who sow corruption with impunity so that the greater part of our kingdom is ruined by them in contempt of Christians and the Catholic faith."[5] Ironically, this description came at a time when the Jewish communities had suffered griev-

ously during the recently concluded civil war between Pedro I and his half brother Henry of Trastámara.

By the 1380s the weakened condition of the Jewish communities and the relativistic philosophy then popular among Jewish intellectuals were producing numerous conversions.[6] After the rioting of 1391, Jews converted en masse, led by their rabbis, and from then on Spain's Jewish communities became smaller and more impoverished while the converted Jews grew in numbers, wealth, and political importance. By the middle of the fifteenth century, however, resentment of the conversos was giving rise to a polemical literature that rejected the possibility of their true conversion to Christianity and blamed them for all the crimes normally attributed to Jews. The most interesting and important of these writings was the Fortalitium Fidei (Fortress of the Faith) by the Franciscan Alonso de Espina, first published in 1460. The work is divided into four volumes, each dedicated to describing the iniquity of one of the four chief enemies of the Catholic faith: heretics, Muslims, Jews, and demons. For Espina, Jews and converts did not exist as a separate category; there were only "public Jews and secret Jews." Since conversos were secret Jews, they were naturally guilty of all the offenses traditionally attributed to Jews by European folk tradition, including profanation of Hosts and the murder of Christian children and the use of their blood or body parts in religious rituals. According to Espina, Jewish law, which is equally binding on both Jews and converts, commands the destruction of Christians and Christianity, which they actively strive to accomplish by starting fires, poisoning wells, and doing other evil deeds.[7]

It was left to the Spanish Inquisition, however, to officialize medieval demonological myths about Jews and apply them to Jewish converts to Christianity in such a way as to keep alive the flames of Spanish anti-Semitism long after the expulsion of the Jews themselves. This process began with the case of the so-called Holy Child (Santo Niño) of La Guardia when both Jews and converts were accused of working together to commit a crime of unimaginable horror which threatened the very existence of Christian Spain. So successful were the inquisitors in this that the La Guardia case served to create in the public imagination a kind of bogyman, a larger-than-life image of the Jew/converso who was at once child murderer, blood sucker, rebel, and demonic sorcerer who sought to reverse the divinely established order of things by destroying Christianity so that, according to Licenciado Vegas, the Holy Child's first chronicler, the Jews "would become the absolute lords of the earth."[8] It was this bogyman who provided the Spanish masses with an ideal object of displaced aggression capable of absorbing the sadomaso-

chistic fantasies and infanticidal impulses that provided the psychological force behind the witchcraft panics in other parts of Europe.

The complexity and sophistication of the Santo Niño legend stands out remarkably when it is compared to the closest contemporary ritual murder accusation of which we have a record: the case of Simon of Trent. This case, which began before Trent's podestá in 1475 and concluded in 1478, involved two elements that were traditionally a part of such accusations: extraction of blood for use in Jewish Passover rituals and the grotesque reenactment of the crucifixion of Christ in order to mock Christianity itself.[9]

Of these two elements, however, it was the use of the child's blood for ritual purposes that clearly predominated while the elements related to the mockery of the Passion and of Christians in general were weaker and clearly of secondary importance. Again and again, the podestá, whose earlier prejudices had been confirmed when a convert assured him that his own father had quaffed glasses of wine mixed with blood on Passover, forced his Jewish victims to enumerate the various ways in which they and their coreligionists used the blood of Christian children. Faithful to the traditions of the medieval ritual murder accusation, Samuel and Tobia, two of the most important defendants, admitted after repeated torture that they drank wine mixed with blood at Passover and they also sprinkled blood on the dough used to make the ritual matzos.[10] The court was also told that Christian blood was routinely fed to pregnant Jewesses so that their babies would be born fat and healthy.[11] In a clear reference to Christian fears about the use by Jews of Calamus Draco, the dark or blood-red gum of a species of palm, to relieve pain after circumcision, the Trent Jews were also forced to admit that they applied wine mixed with blood to the circumcision wound.[12]

Of course the truth, the fact that Judaism categorically prohibits its adherents from consuming blood as in Leviticus 17:11–13, did have a way of coming out in proceedings of this nature, and the case of Simon of Trent was no exception. At one point, the podestá asked Mose, one of the defendants, very directly why Jews drank Christian blood when their own law prohibits the consumption of blood in any form. Mose's reply neatly disposed of this issue, however, when he declared that the law applied only to the blood of animals and not to the blood of Christian children, which is consumed to show disdain for Christianity. After another session in the torture chamber, Mose even stated that leading rabbinical authorities had openly declared that it was no sin to consume the blood of Christians. In this way, through careful stage-management and the liberal application of torture, the podestá's potentially embar-

rassing question was turned into yet another way of adding to the trial record more "evidence" of the Jews' insatiable thirst for blood.[13]

Consistent with the emphasis placed on the ritual use of blood by Jews rather than the reenactment of Christ's Passion, the wounds allegedly inflicted on the hapless Simon seem almost haphazard rather than designed to imitate those inflicted on Christ. Simon's cheeks were torn with pincers, his body stuck with pins in many places and then the pincers were used to inflict a wound on his shins from which blood was collected.[14]

In contrast with the vivid imagery invoked to describe the collection and ritual use of Christian blood, the testimony that was forced out of the accused relating to their mockery of Christ's Passion seems strained and unnatural, almost as though the judges themselves were less than convinced of its centrality to the case. In the first place, although Simon was allegedly crucified, this was almost an afterthought since he received most of his wounds before his arms were extended to form a cross and he died shortly thereafter.[15] Furthermore, the description of the actual mockery of Simon's body is clumsy and childlike; the Jews were even made to testify that they had stuck their tongues out and shown their bare buttocks to the corpse.[16]

The case of the Santo Niño de La Guardia involved six Jews and five conversos from the villages of La Guardia and Tembleque near Toledo and was tried between December 1490 and 16 November 1491, when the accused were burned at the stake. From its very inception, the trial unfolded in an atmosphere of intense anti-Semitism stirred up by the Inquisition's tremendous wave of prosecution against the converted Jews of the Toledo region beginning in 1486. Surprisingly enough, however, the case was not brought before the Toledo tribunal. Instead, it was heard by a special inquisitorial court convened under the watchful eye of Inquisitor General Tomás de Torquemada in the monastery which he himself had founded with money confiscated from the converted Jewish victims of the Holy Office: Santo Tomás of Avila.[17]

In the trial record, the blood libel itself represents only a minor chord in a complex variety of charges. Of course blood was allegedly drawn from the child's body and collected in an earthenware jug, but it was removed by Lope Franco, one of the accused, after the child was brought out for burial. Apart from this, the case omits any mention of the elements that normally comprised the blood libel and which figure so prominently in the Simon of Trent legend. Rather than concentrating on the ritual use of Christian blood by Jews, the case of the Santo Niño brings together a series of charges that are most often separated in

medieval anti-Semitic folk tradition. The affair of the Santo Niño was alleged to have begun as a Jewish plot to use black magic in order to destroy first the inquisitors and then all Christians. According to the confused and often contradictory testimony that was extorted from Yuce Franco, one of the tribunals' Jewish prisoners, this plot started as early as 1487 and involved the employment of Rabbi Abenamias, a master magician, living in Zamora.[18] Abenamias was to be responsible for casting an evil spell using a heart torn from the body of a Christian child and a consecrated Host, both of which would be obtained for him by the accused.[19]

Furthermore, the plotters were alleged to have gone to great lengths in order to imitate Christ's Passion down to the smallest detail. On 24 September 1491, Benito García, one of the hapless conversos, was accused of having carried the child to a cave near La Guardia where he had been nailed to a wooden cross, lashed repeatedly, and a crown of thorns placed on his head.[20] While the child was being beaten, his supposed torturers recited curses designed to mock Christ for whom the child was a substitute. Among other things, Christ was called a "traitor and deceiver who had preached lies against the Jewish faith," an "evil sorcerer who had sought to destroy the Jews and Judaism," and the "bastard son of a perverse and adulterous woman."[21] In this way, out of the pain and torment inflicted on their Jewish and converso victims, Avila's special inquisitors had managed to concoct an extraordinarily suggestive myth which lent itself easily to being further elaborated and made more horrifying by later authors.

We can see how this process began in the very first known account of the case, the Memoria muy verdadera de la pasion y martirio, que el glorioso martir, inocente niño llamado Cristobal, padescio . . . en esta villa de la guardia, written in 1544 by Licenciado Vegas, the apostolic notary of the village. In the Memoria verdadera the vague plot to destroy Christians through enchantment is assimilated to the tradition of Jewish poisoners that had cost so many innocent lives during the Black Death and other periods of unexplained epidemics. Drawing upon a French folktale from some time after the Black Death, Vegas makes the story of the Santo Niño begin in France with the frustrated attempt by several of the individuals involved in the case or their ancestors to poison the wells there with a magic powder made from the heart of a Christian child and a consecrated Host. They were successful in obtaining the Host but were thwarted in their efforts to secure the heart of a Christian child and were tricked into accepting a pig's heart instead.[22] Of course the maleficia that they were planning failed, but somehow these Jews or their descendants

found their way down to Castile, converted nominally to Christianity, and chose La Guardia as the ideal spot to try their enchantment because of its allegedly close resemblance to Jerusalem. But this time, instead of relying on the impoverished parents of the child to murder him and supply his heart as they had done in France, they determined to kidnap a child (whose name turned out to be Christobalico) and cut his heart out themselves after carrying out a mock crucifixion.[23]

It is in describing this crucifixion that Vegas gives free reign to his imagination, transforming the meager details contained in the tribunal's final sentence into a richly detailed imitation of Christ's entire Passion as suffered by the child martyr. According to Vegas's perfervid account, little Christobalico was first forced to carry a heavy cross up the hill to the cave where he was to be crucified. Before he was crucified he was given no less than 6,200 lashes, although we are told that the child informed his tormentors that only the last one thousand really hurt because they were more than Christ himself received.[24]

Vegas's account, which must have circulated widely in Toledo since it was copied by the converso Sebastián de Horozco (1510–1581), was incorporated into Licenciado Sebastián de Nieva Calvos's El niño inocente; hijo de Toledo y martyr en La Guardia . It is in this work, published in 1628, where the Jew/witch connection is made quite explicit. Jews and conversos involved in the Santo Niño affair are depicted as fiendish, physically repellent creatures acting with the support of the devil to carry out his purposes in the world. Benito García de las Mesuras, for example, is described as having an appearance so horrible as to "menace with destruction not only some poor innocent but even the most resolutely defended kingdom." His close associate, Garci Franco, had a "depraved expression" and was so ugly that "it would not be strange if he were to be the executioner of the wrath of heaven." Franco had such an evil reputation in La Guardia that mothers would frighten their noisy or disobedient children by threatening them with his appearance. For his part, Franco is said to have gloried in the hatred and abhorrence of his neighbors, which helped to keep his "vindictive rage against Catholics" at a fever pitch.[25] Like the witches described by Sprenger and Kramer in the Malleus Maleficarum, Benito García, Garci Franco, and their companions had made an explicit pact with the Devil, who sought their perdition by convincing them that they could destroy using the very things with which God gave life to the body and the spirit: the human heart and the consecrated Host.[26]

After Vegas's account was published, the myth of the Santo Niño took hold of the popular imagination and became the subject of plays by Lope

de Vega and José de Cañizares and sermons by such popular preachers as Fray Damián López de Haro (Toledo Cathedral, 1614). Little Christobalico became a patron saint of La Guardia and his shrine received visits from such luminaries as Ferdinand the Catholic, Charles V, and Philip II.[27] The case also figured prominently in the anti-Semitic writings of the period, including Fray Francisco de Torrejoncillo's fanatical Centenella contra los judios, where it served to demonstrate the "intense hatred" felt by Jews for Christianity.[28]

By the mid-sixteenth century, however, the story of the Santo Niño had become just one element in a pervasive anti-Semitism that was directed first against the Spanish conversos and later against the Portuguese New Christians who came to Spain after the union of the two crowns in 1580. Thus, in Spain and Portugal anti-Semitism was not just a social atavism but had real potential victims who were persecuted and discriminated against as much for their racial origins as for their religious practices. The infamous limpieza de sangre statutes that required genealogical investigations designed to prevent the descendants of Jews from entering honorable corporations only really took hold after the major centers of Spanish crypto-Judaism had been exterminated.[29] For its part, the Inquisition kept popular anti-Semitism at a fever pitch with spectacular show trials directed at prominent New Christian financiers like Joao Nunes Saraiva and his brother Henrique, who appeared at the auto de fe of 1636 in spite of their staunch protestations of fervent Roman Catholic belief.[30] Spain's Old Christian ruling elite was quick to see the hand of the Jew behind any threat to the faith. As early as 1556 Philip II expressed the view that "all the heresies which have existed in Germany and France . . . have been sown by the descendants of Jews."[31]

Interestingly enough, at around the same time that anti-Semitic ordinances were being passed by more and more Spanish institutions, the Spanish Inquisition began staking out a moderate position for itself on the witchcraft issue. In 1526, just one year after the Franciscan Order adopted a limpieza statute, the Inquisition held an important meeting in Granada to discuss its policy toward the witchcraft trials that were beginning to take place with increasing frequency in northern Spain. After careful deliberation, four of the ten inquisitors present, including future Inquisitor General Hernando de Valdés, voted that witches only went to the Sabbath "in their imagination." Those present at the meeting also decided that henceforth witches should be tried by the Holy Office because the murders that witches confessed might be mere illusions.[32]

In spite of the lack of unanimity on the issue of the Sabbath, the 1526 meeting set the tone for the Inquisition's attitude toward witchcraft

cases. In 1538, when witches were accused of having caused harvest failures and other evils, the local inquisitor was instructed to explain that these things are "either sent by God for our sins or are a result of bad weather, and that witches should not be suspected." In August 1614, in reaction to the Logroño auto de fe of 1610 at which six persons accused of witchcraft were burned, the Suprema officially adopted a skeptical attitude toward the crimes supposedly committed by witches and embodied that attitude in a set of instructions meant to guide local inquisitorial tribunals.[33] In fact, the 1614 instructions changed little because, with the sole exception of the inquisitors of Logroño in 1609–1610, local inquisitors tended to be extremely unwilling to hand down harsh sentences in cases that would have earned the death penalty in France or the Holy Roman Empire during the same period.[34]

By officializing medieval anti-Semitic folk traditions and extending them from the Jews to the conversos through a well-publicized show trial, the Spanish Inquisition made sure that anti-Semitism and not Scholastic witch theory would answer the early modern Spaniards' craving for an object of social aggression. Moreover, even though France and the Holy Roman Empire shared many of the same folk beliefs about Jewish iniquity and diabolism, Jews could not provide them with an effective object for collective anxiety and frustrations. The Jews of France had been expelled in 1394 and, even though the decree was repeated in 1615, the sight of Jews was so rare in France that they were regarded as an exotic sight when Frenchmen met them while traveling abroad.[35] In sixteenth- and seventeenth-century France witches and Huguenots assumed a "Jewish" role and were widely accused of many of the same things of which the Jews had been accused in former times.[36] In the Holy Roman Empire most Jews were expelled during the sixteenth century and both Catholic and Protestant focused on the witch as an ideal scapegoat for social ills.[37] Only Spain and Portugal among the great European states of the early modern period could combine theories of Jewish diabolism and implacable hatred of the true faith with the actual presence on their territories of large numbers of persons of Jewish origin. Significantly, serious witch persecution in Spain was mainly confined to the Basque region, precisely the area that had had least contact with Jews in the Middle Ages. For the rest of the country the converted Jew substituted for the witch as a pariah, reflecting through antithesis and projection society's most ingrained fears and repressed longings.

Perpetuated in plays, paintings, and histories down to 1955 when Ramón Saravia published his El Santo Niño de La Guardia through a Catholic press specializing in children's books, the myth of Jewish in-

iquity represented by the Santo Niño legend has contributed powerfully to that curious Spanish phenomenon: anti-Semitism without Jews. Even today, in a Spain increasingly secular, pragmatic, and cosmopolitan, the legend of the holy child prowls around like the ghost of past intolerance. Christobalico, the holy martyr, remains the patron Saint of La Guardia, and the Church, which in the mid-1960s disavowed the Simon of Trent blood libel, continues to support and profit financially from the annual celebrations that commemorate the creation of the far more dangerous anti-Semitic myth of the Santo Niño de La Guardia.

Nine—

On Knowing Other People's Lives, Inquisitorially and Artistically

Joseph H. Silverman

The epigraph for my essay comes from the play by Lope de Vega, El niño inocente de La Guardia . Its words—spoken by a Jew—are a dramatic summation of many significant aspects of this conference:

What King and Queen are these [Ferdinand and

Isabella] who

through such chimeric schemes

—based on secret counsel—

would send into exile those

who scarcely offend them?

What flames are these, rekindled

from ash by Dominican hordes?

What new Cross is this, black and white,

that delights the Catholics so?

What new mode of scrutiny and

legal system have we here?

Why are trials now held in secret?

Oh, if only Spain had never known such rulers!

Woe unto us, exiled from our own

fatherland in such misery!

The suffering that so long ago was foretold

has not yet ceased and our

punishment is unending.

(Pp. 59–60)

In an unforgettable moment of epiphanic self-revelation, the squire in the anonymous sixteenth-century novel Lazarillo de Tormes confesses to his young servant that, if he had a chance to serve a noble master, he

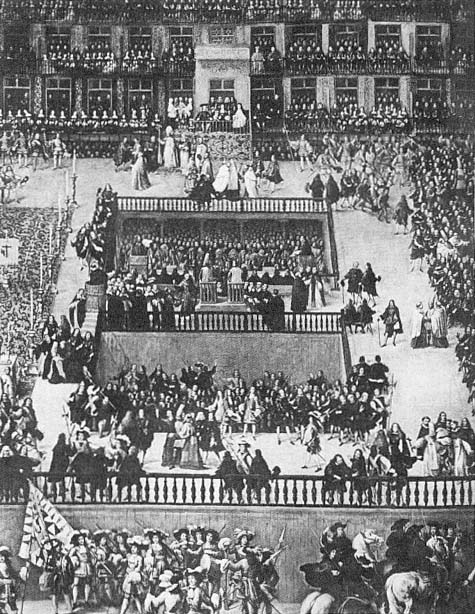

Fig. 6.

Auto de fe by Pedro Berruguete.

would—among other virtuous (!) acts—"be malicious, mocking, and a trouble-maker, a malsín , among those of the house and outsiders; [he'd] go prying and trying to know other people's lives so [he] could tell his master about them. And [he'd] do all kinds of other things of this sort which are the vogue in palaces today and please the nobility well" (p. 57). As Covarrubias informs us in his Tesoro de la lengua , the malsín, a word of Hebraic derivation, is "that individual who secretly warns the authorities of the transgressions of others with evil intention and self-interest, and to perform this function is called malsinar" (p. 781b).

The phrase to know other people's lives in this context, closely allied with the activities of the malsín, persuaded me to offer, in 1961, a very negative appraisal of the squire, in contrast with Azorín's judgment of him as the most noble and worthy in Spanish history. But, more importantly, the words saber vidas ajenas , "to know other people's lives" were to become a signpost in my reading and teaching, which in the early 1950s were influenced by the irresistible imperative dimension of the writings and person of Américo Castro. And so, over the years, I collected examples of the phrase, in its exact form or in words that suggested its meaning, which inevitably led me to see the aspects of Golden Age literature I now want to evoke, basing myself on Mordecai M. Kaplan's premise that the full meaning of any text cannot be derived from the contemplation of the text itself, apart from the social, economic, psychological, and intellectual setting to which it belongs.

Antonio de Guevara, who always seems to be saying more than his words denote, even in those commonplace truths and fabulous lies that he manipulates between the remote past and his own moment, writes:

Among the inhabitants of Crete it was customary, even obligatory, not to dare ask any visitor from a foreign land who he was, what he wanted, and from where he had come, under penalty of being whipped or sent into exile. And the purpose involved in promulgating such laws was to rid men of the temptation to be curious, that is to say, to want to know other people's lives and not pay attention to their own. . . . For what men seem to devote most of their time to is asking and investigating what their neighbors are doing; what they're involved in, how they support themselves, with whom they have dealings, where they go, what places they enter and even what they're thinking; because it is not enough that they insist on asking, they even presume to guess . . . For this reason Plato said: "Know thou, if thou knowest not . . . , that the sum of all our philosophizing is to persuade and counsel men that each one should be the judge of his own life and not be concerned to scrutinize the lives of others ." (Menosprecio , 30–36)

It goes without saying—though I'll say it anyway—that despite his reference to Plato's "Know thyself" and the realm of philosophy, Guevara is really talking about what Francisco Márquez termed "el problema del rigor inquisitorial" (p. 350). Elsewhere, becoming more specific about the potential danger and destructiveness involved in knowing other people's lives, that is, saber vidas ajenas as a weapon of an Inquisition-crazed society, he observes that "I have never seen a man insult another without prying into the life he was leading, without scrutinizing his blood line, [every branch and twig of his genealogical tree] . . . or without disinterring his ancestors" (pp. 375–382). These last remarks appear in a letter addressed to a friend who had called recent converts to Christianity "dogs, Moors, Jews, and pigs." With even greater force and specificity, Guevara writes that

one solitary blemish will dishonor an entire generation. A stain on the lineage of some country bumpkin affects no one beyond him, but a stain on an hildalgo's blood affects his entire family, because it sullies the reputation of his forebears, it serves to disinter his ancestors, it leads to the investigation of his living relatives, and it corrupts the blood of those yet to be born. (Pp. 441–442)

Now, Guevara is writing these last words in answer to an Italian gentleman who had sought to implicate Fray Antonio in the disappearance of a vial of perfume. But we can hardly believe that this is the kind of offense that would destroy a family's reputation retrospectively and proleptically. Guevara's broader and deeper meaning—his condemnation of irrational intolerance—is more apparent against the background of an earlier remark to his Italian accuser: "I, sir, am determined to pay no attention to your insult, nor to respond with anger to your letter, for I take much more pride in the religious order I belong to than in the pure blood of my ancestors . . ." (p. 440).

Alonzo de Orozco, in his Victory of Death , proclaims:

O sinner, you who go lost and wandering through the sea of life! Do you want to know why every passion stirs you and draws you after it? The reason is that you forget death, because it seems to you that you are immortal . . . In the dead man's house there is the only true philosophy . . . , but in the gatherings of the living they speak of other people's lives, and not being content to speak ill of the living, they engage in a greater cruelty: they disinter the dead, with great offense to God and infamy to those who died. (P. 136 n. 7)

It is scarcely necessary to mention that the dead alluded to here are the ancestors of New Christians, or that the disinterring of the dead is an

analogue of the inquisitorial practice of exhuming and burning the mortal remains of discovered secret Jews. In 1580—as C. R. Boxer has noted—the remains of the great pioneer of tropical medicine, Garcia d'Orta, "were exhumed and solemnly burned in an auto de fe held at Goa, in accordance with the posthumous punishment inflicted on crypto-Jews who had escaped the stake in their lifetime" (p. 11). For the Judeo-Christian Mateo Alemán, those who dug for this kind of information were like hyenas "who nourish themselves on the dead bodies they disinter" (1:48). Through the animal imagery Alemán communicated what Stephen Gilman called the full horror of inquisitorial dehumanization (p. 179). Juan de Zabaleta observed that "the malicious curiosity of men is so penetrating that it perceives blemishes in the bones of those who lie buried" (p. 247). And Gracián—writing with aphoristic density—recommends that "one should not be in life a book of vital statistics, an archive of genealogies and family traditions, for to concern oneself with the infamy in other people's lives is usually an indication of one's own tainted reputation. . . ." "In such matters," he concludes, "the one who digs the deepest will be most covered with mud," for which reason one must avoid at all costs "the effort to be a walking registry of others' ignominy, which is to be, though alive, like a soulless and despised public record of the Inquisition's trials and convictions" (p. 85 no. 125). In Quevedo's Buscón , don Pablillos's mother is imprisoned by the Inquisition of Toledo "because she disinterred corpses," but not because she did it in order to know other people's lives or to destroy a reputation by discovering some trace of Jewish blood, as an inquisitor in her own right, but because, as a witch with tainted blood no less, she literally disinterred freshly buried bodies, so that "in her house were found more legs, arms, and heads than in a shrine for miracles" (p. 94). The meaning of "to know other people's lives," then, in all these contexts and any number of others that could be cited, tells us something about the inquisitorial bent of the world in which Cervantes lived while writing Don Quixote , a world in which these words from La Celestina had disastrous validity: "When you tell someone your secret, your freedom is gone" (p. 57). In Cervantes's Colloquy of the Dogs , Cipión suggests to his friend Berganza that they should take turns relating their lives, "because it will be better to spend the time in telling their own lives than in delving into the lives of others ." At another point, while discussing police officers and notaries, Cipión observes that not all notaries are corrupt, "for there are many notaries who are good, faithful, law-abiding, and eager to please without harming anybody; for not all of them extend lawsuits, or advise both parties, or pocket more than what they're entitled to; nor do they

go searching and prying into other people's lives to put them under suspicion with the law [or the Inquisition]."

In another vein, but even closer to my subject, are these words spoken yet again by Cipión, who knows something about the difficulties of finding a decent job:

The lords of the earth are very different from the Lord of Heaven. The former, before they accept a servant, first examine his lineage as if they were looking for fleas, then they scrutinize his qualifications and even wish to know what clothes he has. But to enter God's service the poorest is the richest, the humblest is the man of most exalted lineage, and so long as he sets out to serve him with purity of heart [not of blood], God orders his name to be written in his wage-book and assigns him such rich rewards that in number and excellence they surpass all his desires.

"All this, friend Cipión, is preaching," says Berganza, and of course it is. But it was a sermon that Moorish dogs (perros moros ) barked and Jewish pigs (marranos judíos ) squealed, that New Christians and even some Old Christians preached, with the hope of achieving in Spain an open society, that kind of society which—in the words of the spiritual New Christian Henri Bergson—"is deemed in principle to embrace all humanity. A dream dreamt, now and again, by chosen souls, it embodies on every occasion something of itself in creations, each of which, through a more or less far-reaching transformation of man, conquers difficulties hitherto unconquerable" (p. 251).