Horton Foote: The Trip from Wharton

Interview by Joseph A. Cincotti

The bench is Pilgrim century. The paintings, about two dozen of them, are early primitives, mostly New England. The subjects don't so much pose as stare. Though the apartment is in New York City's Greenwich Village, a short stroll from the Hudson River, the feel is that of a decorous front room, a room you might find in one of the better homes of a small rural town, like, say, Wharton, Texas. The Two Academy Awards won by the resident of the apartment are not in evidence.

A number of years ago, Albert Horton Foote bought the last two available grave sites in the Wharton cemetery. In 1993, his wife, Lillian, his sometime producer and constant confidante, was laid to rest in one of them.

In Wharton, the live theater is confined to pageants at the local church. There is no movie theater. The last picture show unspooled awhile back. However, thanks to the ubiquity of the video store, most of the Foote oeuvre is available, even there, for rent.

But for the breadth of his acclaim, Horton Foote, the most famous son of Wharton, Texas, might be classified as a regional writer. The affinities are obvious between Foote and William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Flannery O'Connor. Foote has fictionalized Wharton into Harrison, his Faulknerian demesne, his Yoknapatawpha County, yet his territory is both broader and narrower, the landscape of the human heart. He is a chronicler of foibles, petty tyrannies, crossed purposes, intentions thwarted and realized in stories spun out in a novel, 34 produced plays, at least 29 teleplays stretching from television's golden age to the era of the miniseries, and 14 films, including To Kill a Mockingbird and Tender Mercies, both of which won him Academy Awards.

His reputation as a screenwriter is secure on the strength of those Academyhonored efforts, and of the films The Trip to Bountiful (which also earned him an Oscar nomination) and Of Mice and Men, directed by and starring Gary Sinise.

He is an actor's writer. His films find their power in the confluence of text and performance. Offhand, you may not recall, in any of Foote's films, a big moment or an immortal line. He eschews the obviously clever line, the overtly theatrical declamation, the profane outburst, the writer's wink. He doesn't write clips for the highlight reel. What he gives actors is the opportunity to build a performance moment to moment. Some take it. Gregory Peck, Robert Duvall, and Geraldine Page—all won Academy Awards for their performances in films he wrote.

As a young man, Foote left Wharton to become an actor. He bounced around Los Angeles, Washington, D.C., and New York, training in the standard American style of the day, before discovering Stanislavski through an emigre disciple, Tamara Daykarhanova. He wrote a scene for an acting class.

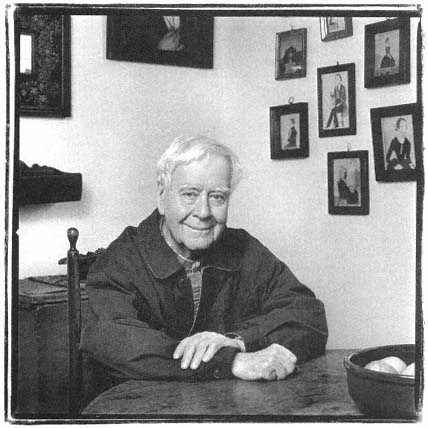

Horton Foote in New York City, 1995.

(Photo by William B. Winburn.)

The scene eventually became a play and in 1941 was produced as Wharton Dance. Foote traded grease paint for a fountain pen. He still writes with a fountain pen today.

Until recently, he has been a quiet but perennial presence in New York theater, the important off-Broadway houses providing a constant if temporary shelter for his work. Then, in 1995, his Young Man from Atlanta won the Pulitzer Prize in Drama. Another play is scheduled to open in New York in 1996, after a circuit through several regional theaters. Although Horton Foote is eighty years old, he has three screenplays in development. Every day, in notebooks or on long legal pads, he writes.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Television credits for Philco-Goodyear Playhouse, Studio One, Playhouse 90, DuPont Play of the Month, and U.S. Steel Hour include "Only the Heart" (1947); "Ludie Brooks" (1951); "The Travelers" (1952); "The Old Beginning" (1952); "The Trip to Bountiful" (1953); "A Young Lady of Property" (1953); "The Oil Well" (1953); "Rocking Chair" (1953); "Expectant Relations" (1953); "Death of an Old Man" (1953); "The Tears of My Sister" (1953); "John Turner Davis" (1953); "The Midnight Caller" (1953); "The Dancers" (1954); "Shadow of Willie Greer" (1954); "The Roads to Home" (1955);

"Flight" (1956); "Drugstore, Sunday Noon" (1956); "Member of the Family" (1957); "Traveling Lady" (1957); "The Old Man" (1959); "Tomorrow" (1959); "The Shape of the River" (1960); "The Night of the Storm" (1961); "The Gambling Heart" (1964). In addition, Foote's television work includes Flannery O'Connor's "The Displaced Person" (1977); William Faulkner's "Barn Burning" (1980); "The Story of a Marriage, Part 1, Courtship" (1987); and "The Habitation of Dragons" (1992).

Plays include Texas Town, Only the Heart, Celebration, The Chase, The Trip to Bountiful, Traveling Lady, The Midnight Caller, John Turner Davis, Tomorrow, A Young Lady of Property, Gone with the Wind (play, with lyrics), Night Seasons, Courtship, 1918, Valentine's Day, In a Coffin in Egypt, The Man Who Climbed Pecan Trees, The Roads to Home (three one-act plays: Nightingale, The Dearest of Friends, and Spring Dance ), The Old Friends, Cousin, Road to the Graveyard, Blind Date, One-Armed Man, The Prisoner's Song, Lily Dale, The Widow Claire, The Habitation of Dragons, Dividing the Estate, Talking Pictures, The Young Man from Atlanta, and Laura Dennis.

Published screenplays include Three Screenplays (To Kill a Mockingbird, Tender Mercies, and The Trip to Bountiful ).

Novels include The Chase.

Academy Award honors include Oscars for Best Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium for To Kill a Mockingbird and Best Original Screenplay for Tender Mercies; and an Oscar nomination for Best Screenplay for The Trip to Bountiful (Adaptation).

Writers Guild Awards include Best Script for To Kill a Mockingbird (Adaptation) and Tender Mercies (Original); and a nomination for Best Script for The Trip to Bountiful. He received the Writers Guild Laurel Award for Lifetime Achievement in 1993.

You said once, when speaking of Harrison, Texas, "I did not chose this task, this place or these people."

No. They chose me. That's absolutely true. I no more consciously chose that than I flew to the moon. The kind of writers that I like, I have a hunch that's mostly true of: that their material chooses them, rather than vice versa. I have tried to write some things about other places, some of them pretty good I hope.

What things are you thinking of?

Assignments. Like adapting a book for a movie, or something like that.

You consider that just an assignment?

Because it isn't something that comes from inside. I try to take assignments very seriously, but they aren't something coming organically from me.

How does it happen that a place chooses you?

I don't know what makes a certain kind of writer interested in a sense of place or time. I only know that it's true of people whom I admire very much: Reynolds Price, who is of course a great novelist, writes about his little patch of North Carolina; Eudora [Welty] writes about Jackson, Mississippi; and Flannery O'Connor wrote about Georgia.

It has nothing to do with good or bad writing. There are certainly wonderful writers that write very differently. But look at Joyce; he lived in Paris and was obsessed with Dublin. He indeed wrote back constantly [to Dublin], asking what happened on this day at this place at this hour—"Can you remember and tell me right away?" Gertrude Stein was very abstract, but even her abstractions, if you understand and know enough about Gertrude Stein, have a basis of some kind of reality, which is often Baltimore and America.

When did you know that Harrison, Texas—or Wharton—was going to have a claim on your imagination?

I always knew that. I think the first thing I ever wrote was called Wharton Dance, and the second thing was called Texas Town. I didn't decide on the name Harrison until later because I really wanted to get away completely from people asking, "Is this about so-and-so, or this or that person?" It helped a little bit to give the place a fictional name.

Is there an element that is oedipal in your writing so much about your mother and your father?

I couldn't really answer that, could I? That's something you would have to decide. I haven't thought about it. It's just what I seem to know. Certainly, I seem to be fascinated with trying to find a pattern or some kind of order to all this.

On the one hand, you have a great affection for your parents. On the other hand, as a writer, you have an absolute duty to be as honest as possible.

Absolutely. It helps that my parents are not here. I can be objective in a way you couldn't be otherwise. Some writers have no feeling for that, but I do; it would worry me. My mother and father openly admitted that these stories were based on them, and I did it because I was very fascinated with their particular journey, but in truth, you know, they're much more of a collage than anything else. I think this is what you do when you're writing. I don't think you're out to just specifically copy. Somehow, the material goes through a transformation.

I understand that after you left home your mother wrote to you every day until the day she died.

Well, not every day, but for a long period of her life, she did. After I got married, it was less—maybe three to four letters a week—but up until then, it was every day. She had a remarkable knack for letter writing. She kept me in touch with that whole world down there.

You've been prolific in your career. Hearing that about your mother, people might think they understand something about your prolificness.

(Laughs. ) I hadn't thought about that. It's true, though my mother had no ambitions as a writer. She was just a natural-born letter writer.

Were you a natural-born letter writer?

No. I didn't like to write letters. I've learned to. I have a daughter who is a natural-born letter writer, and I've realized it's very important to write letters.

When you were in California as a young man—then in New York and Washington—what effect did her letters have on you, coming so frequently, as a developing writer?

I think they had a great effect on me because I was able to keep in touch with people and things that I wouldn't have known about ordinarily. Without any strain, they just kept me in touch with the dailiness of their lives and the lives of that town; and it was that dailiness that always interested me. She didn't necessarily write me a sensational, gossipy letter, although once in a while, she'd tell me something out of the ordinary, but mostly, it was a kind of record of their day-by-day living and the living of people around them—we had a large, extended family.

Do you ever pull these letters out to help you with your writing?

Unfortunately, no. Unfortunately, many of them are gone. I'm sick about it.

What happened to them?

When you're young and you're living from hand to mouth and you don't know where your next meal is coming from and you're moving around a lot—because you can't pay the rent—you just don't hold on to things. I wish I had them, but I don't. But they're all in here somewhere. (Points to his head. ) That's the important thing. They were an enormous help to me.

Did you get to the point where you could discern the subtext of your mother's letters? Were there things unwritten in your mother's letters?

I haven't ever thought about it. Actually, I wouldn't think so, because she was very explicit, nothing veiled or hidden at all. That's one thing I learned as an actor: to search for the subtext in the material. I never think about it while I'm writing, but later on, I'm delighted if one senses a subtext.

I know you studied for a long time as an actor and were influenced by the Method. Can you tell me a little bit about Tamara Daykarhanova?

I stumbled on her early when I was a young actor. A very well-known actress of the 1930s, named Rosamond Pinchot, met me on the street in New York and told me she would pay me to be her scene partner, working with Tamara. That's how I met Tamara. Tamara Daykarhanova was a student of Stanislavski's, who had been with a very famous revue called Balieff's Chauve Souris, which toured Europe. Her husband [the aeronautical engineer Sergius Vassiliev] got into deep political trouble with the interim government before the Communist government, so they had to leave Russia. They came over here

and first worked with [Maria] Ouspenskaya, who had started the American Laboratory Theatre and was a very famous teacher of the method. When Ouspenskaya went to Hollywood, Tamara started her own studio [the Tamar Daykarhanova School for the Stage]. She brought into the studio Andrius Jilinsky and [his wife] Vera Soloviova, both from the Moscow Art Theater, who had been members of Michael Chekhov's company. They taught the Stanislavski system, which I am very indebted to because it taught me a great deal about play structure. I worked in Tarmara's studio with Vera for about two years, out of which we started a company called the American Actors Company [in 1938]. I guess, you'd call it an off-off-Broadway company now, but it was over a garage. That is where I first started writing.

Vera was really a great influence. I kept in touch with her through the years. She had been in Stanlislavski's famous production of [Charles Dickens's] Cricket on the Hearth, playing the blind sister, and then she was the second Nina in The Cherry Orchard, replacing the original Nina. She and Andrius Jilinsky were both members of [Eugene] Vaktahngov's first studio and of course were very steeped in the Method. Having also worked with Michael Chekhov, they had their own approach to acting.[*]

What did she teach you?

First of all, for me there was a whole period of unlearning the bad habits I had picked up in my conventional training as an actor, which was to be very vocal and to work things out vocally rather than to find my inner life. They gave us a whole series of exercises for actors—

Including the circles of attention?

Jilinsky taught that technique. We really did scene study with Vera.

Are you still, these fifty or more years later, influenced by the Method? Do you still find yourself writing in the beat?

Absolutely. The whole sense of the through-line, the sense of actions, what people want on stage.

Can you explain what the 'beat' is?

It's just an arbitrary term. It's like, what is the beginning of an action and the end of an action, you might say. The first beat of the play might be any moment that begins and ends.

The smallest unit of acting?

It could be. As you work on, you try to make the beats larger. At first, you might break them down into infinitesimal beats; then you try to make them larger. Some people use the term 'beats.' Other people use the term 'actions.' It

* Additional background on Stanislavski's disciples in America can be found in Christine Edwards's Stanislavsky Heritage: Its Contribution to the Russian and American Theatre (New York: New York University Press, 1965), which makes mention of the American Actors Company and Horton Foote.

all means the same thing, really. The reason I like to use the word 'beat' is it's almost a musical term. It's like a musical phrase.

How did the Stanislavski system or method help you as a writer?

It applied to me wonderfully as a writer, because in my work as an actor, I would break a play down so that, without really knowing it, I was studying its structure in the sense of what it was the characters wanted. That's really much more important than the result of the character: what do they want, what causes the conflict between them, what is the structure of the scene, what is the overall through-line of the play, what is the spine, what does everything kind of hold on to. That was one way in which I could instinctually, as an actor, work on trying to understand the play.

Can you think of any other writers you would consider Method or system writers?

Oh, I don't think anybody in the modern theater has escaped it. They may think they have. They may disallow it or think it's tiresome or unnecessary. But you can't be in our theater and not have been, on some level, influenced either for or against the system or the Method. How is that possible?

What kind of career do you think you would have had as an actor if you hadn't become a writer?

Oh, my God, I don't know. I shudder to think of it, because I don't think I could take the pressure an actor has to go through. I loved acting, but I wasn't happy acting like I am happy writing. I loved it, and certain parts were very easy for me, but then other parts were very difficult. There are some actors that just enjoy taking on any role and finding certain things in it for them. I had to take roles that I felt instinctively in sympathy with. But I didn't act for very long, and we are talking about a long time ago.

Can you tell me about the gestation and incarnations of The Trip to Bountiful—from Lillian Gish to Geraldine Page?

Oh, well! Fred Coe was a remarkable man and remarkable producer.[*] He had started the Philco-Goodyear Playhouse, and was commissioning people to write television plays. I had done one for him, and he was anxious that I do another. You had to go in and tell him just a few lines of the script, which I have always felt was a horrendous experience.

Sort of a pitch?

We'd call it a pitch today. It was a sort of gentle, mild one, but that's exactly what it was.

I had an idea based on a certain situation in my family that haunted me. Originally, I had tried to start the story of The Trip to Bountiful on the day that Mrs. Watts was forced by her father to marry her husband—emotionally, if not

* See the Jay Presson Allen and Arnold Schulman interviews for additional Backstory 3 reminiscences about the producer-director Fred Coe.

physically, forced—and the story just wasn't working. By that time, I knew enough to know that you can't use your well if it's not working. So I just put the work aside, and I don't know how or why—what the mechanics were—but a couple of days later, I realized I had started the story all wrong. I decided I had to start at the end of her life. When I did that, I wrote the script very quickly.

I could never tell one of my stories until after it was written, because it would ruin it for me. After I wrote it, I went down to see Fred and told him the story. He used to say that all I told him was something about this old lady who wanted to get back home. I don't believe that; maybe it's true. Then, he used to say—he always laughed about this—"Two days later, you sent me a full script." Of course, the script was already written.

Well, we did the play on television, and of course, it was 'live'. None of us realized the power and phenomenon of the play, but that night we began to sense it, because after the show the phones in the studio started to ring, and they rang and rang. People were calling and talking about Lillian Gish [who played the leading role of Mrs. Carrie Watts]. They had seen her performance and were excited because they had not seen her for years. The response was so emotional.

Then the Theatre Guild asked me if I would turn it into a full-length play, and I did.

It only ran thirty-nine performances, right?

No, more than that. First, we did it at Westport [a theater in Connecticut] for a week. Then we took it to Wilmington and Philadelphia before we brought it into New York. Lillian had an enormous success in it, and Jo Van Fleet [as Jessie Mae Watts, the daughter-in-law who hates Mrs. Watts] won the Tony that year. The out-of-town notices had been just stunning, but the New York notices were disappointing—okay, but not what we hoped. Then we had a newspaper strike, and it was rough. But the play had great partisans, even then. People would come to it three times to see it. People who liked the play liked it a lot. It was [Brooks] Atkinson whom we expected to just fling his hat in the air, because he had been very kind to me in other reviews. He loved Lillian Gish and was kind to the play, but dismissive.[*]

So the play began to have a legend. People remembered the production with fondness. Over the years, I had many movie offers, but I kept turning them down because I wanted Lillian, very badly, to play the part; and in those days, Hollywood felt she wasn't bankable. People tried to talk me into all

* Brooks Atkinson, in his New York Times review of November 4, 1953, praised Lillian Gish's performance as a "masterpiece," but said of the play that it did "not make for a very substantial play for a whole evening. Nor does Mr. Foote make things any better by underwriting. He is a scrupulous author who does not want easy victories, and that is to his credit morally. But he might also do a little more for the theatre by going to Bountiful himself as a writer, providing his play with more substance and varying his literary style."

kinds of other actresses they felt were bankable—like [Katharine] Hepburnmdash;all very interesting women. But I just said, "No, this role belongs to Lillian Gish." When she hit ninety, I realized it was a losing cause, and I couldn't do anything about it any longer.

That's when [the director] Peter Masterson called me up and said he wanted to do a film and this was his choice. I said, "First thing, Pete, the stumbling block is, who is going to play the part?" He said, "What about Lillian?" I said, "I have to tell you. I think she's too old now. The whole point of Mrs. Watts is that she isn't really a very old woman—[they] have put her into that category. And secondly, I don't think, physically, she can take the job. If you ask her, she'll say yes; so don't dare ask her." I never saw Lillian after that. I hope she forgave me, but she knew how loyal I had been up until that time. It must have been hard on her, because she loved the part.

Did you rewrite the play in those intervening years?

No, never.

Did you do some rewriting for the film?

For the film, I added things, of course. You had to. It was the first time I could actually take the trip, because in the days of live television, the restrictions of television were much like theater. Peter said, "Who do you want in the part, then?" I said, "I want Geraldine Page." He said, "I absolutely agree." That was it. Except nobody wanted Geraldine Page. People suggested Anne

Rebecca De Mornay (left) and Geraldine Page in the film The Trip to Bountiful.

Bancroft or Jessica Tandy—I can't tell you who all they wanted. But I can be stubborn. I just bulled my neck and said, "Well, we're not going to do it unless . . . " Peter and Sterling [Van Wagenen], who was by then the coproducer [with Foote], backed me up. Of course, once we got Geraldine, they were all happy, as well they should have been.

How was Geraldine Page's Carrie Watts different from Lillian Gish's?

Oh, I know how. I'll tell you one thing that everybody says: "Lillian was very ethereal." That's not so. Lillian had certain qualities that seemed ethereal, and at moments, she had great spirituality, but she was as tough as a pine knot. She really was strong and had as much strength as Geraldine Page. Geraldine didn't play it quite as purposefully belligerent; she played it more slyly than Lillian. But they were both wonderful.

I'll tell you who was also remarkable in it just recently—Ellen Burstyn. She was in a revival of the play almost two years ago. She was extraordinary. The root was the same, but she was different. So I've had three remarkable actresses, very different from each other.

Where do you think that piece of work works best—on television, on the stage, or in film?

In all three, it worked well in its own time. Certainly, Lillian was more effective in some ways in the theater, because she had more space to work with and she had a wonderful company. Geraldine, of course, gave a landmark performance. For this last production, the play also had real vitality, and the audiences just ate it up. I never tire of watching it. I'm very impersonal about it. It's almost as though I didn't write it.

Tell me a little bit about your first screen credit, Storm Fear.

It was a learning experience because I knew nothing about the movies. I took the job because I rather liked certain things about the book [Storm Fear, by Clinton Seeley (New York: Holt, 1954)], and I liked Cornel Wilde.

Why did he come to you?

I think because someone had seen my play Traveling Lady and told him about it. He, in those days, was doing films for little money, and since this was my first film, I think he thought he could get a good writer for little money, if you want me to be truthful about it.

Did you go out to Hollywood for a time?

Yes, I did. Not during the shooting but just to work on the script.

Was Cornel Wilde helpful to you at all in terms of the script?

No, but he didn't interfere in any way. I liked working with him. I worked with Cornel at his house and at Columbia. There were certain things we talked about, but in the end, I just plunged in and did it.

Did you have contact with any other Hollywood writers?

Mostly people that I had known before, mostly theater or live television writers. And there were some actors I'd known that I was in touch with. But I was on my own with that script.

Did you have any particular impression of Hollywood at that time?

Not too much, except to save my money and get out of there as quickly as I could.

Why "quickly"?

I just didn't feel that it was a place for writers to be, and I still don't think so.

I think when people hear your name, what immediately comes to mind is the big three or four films: To Kill a Mockingbird, Tender Mercies, The Trip to Bountiful, and Of Mice and Men. Perhaps they are less familiar with your plays. How do you feel about that?

I can't help it. Nothing I can do about it. Those things right themselves. My plays are being done now a great deal outside of New York.

Can we talk about To Kill a Mockingbird and Of Mice and Men? When your telephone rings and someone asks you to adapt a work of literature, what is your reaction?

Well, I don't like to adapt, to begin with. It's a very painful process—a big responsibility—particularly if you like something, which I usually have to do. In the case of Mockingbird, it was sent to me, and I said, "I'm not going to read it because I don't want to do it." My wife read it—she's passed on now—but she had enormous influence on me. She said to me, "You'd better stop and read this book." So I read it and felt I could really do something with it. [The producer] Alan [Pakula] and [the director] Bob [Mulligan] had offered it to Harper [Lee, the book's author] to adapt, and she didn't want to do it. They felt she and I should meet, so they brought Harper out to Nyack, and we had an evening together and kind of fell in love. That script was a very happy experience.

Was it harder or easier to adapt than you thought it would be?

Not hard, because first of all, Alan Pakula was the producer, and he's very skillful. I have to find ways to get into things. I had read R. P. Blackmur, a critic I admired, and he wrote a review-essay about it called "A Scout in the Wilderness," comparing the novel to Huck Finn. That meant a lot to me because Huck Finn was something I always wanted to do and still would like to do as a film—if you could, although you would have to wait until the era of being politically correct about it has passed. The comparison to Huck Finn made my imagination go.

Harper also told me that [the character of] Deal was based on Truman Capote, and that was very helpful to me. The contribution Alan made was to say, "Now look, just stop worrying about the time frame of the novel and try to bring it into focus in one year of seasons: fall, winter, spring, summer." Architecturally, that was a big help. Then I felt I could compress and take away and add from that point of view.

Of Mice and Men, again I resisted. But I had great respect for [the actordirector] Gary Sinise. My great resistance there was it had been done so much—what in the world could anybody ever say that was different? I had

spent my young manhood pretending I was Lenny. (Foote does an imitation. ) Everybody was doing Lenny in those days. But then I reread the novella, and I was struck by how fresh it seemed, particularly how it related to today, with the rootlessness and the hopelessness and the migratory conditions. I felt quite taken with it. Then—I know I'll get into trouble for saying this, because it's considered a classic—I happened to run off the [Lewis] Milestone film [Of Mice and Men, 1940], which I decided was terrible. I thought it was full of clich́s and everything I didn't want to do. Gary agreed with me. He said, "Don't pay any attention to that silly thing." He had a great passion about the male-bonding idea. He sent me a film, which I'd never seen, called Scarecrow, with Al Pacino, who I think is a remarkable actor, and Gene Hackman, also a wonderful actor. It is a tale of two guys on the road—very different from Steinbeck—but suddenly, I found myself interested in doing Of Mice and Men and exploring it.

Were you on the set of all of your big four films?

No, just the middle two [Tender Mercies and The Trip to Bountiful ]. For Mockingbird, I was there for all of the casting. I did some of the screen tests. I played Gregory [Peck's] part in some of the screen tests with the kids. With [Gary] Sinise, I was there for the first week, and I went back the last week.

On 1918, On Valentine's Day, and Courtship, you functioned almost as a codirector.

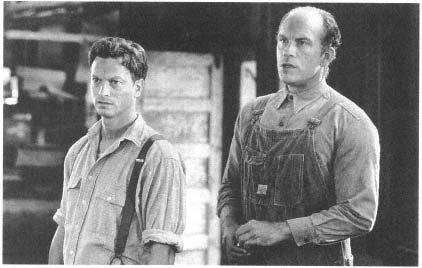

Gary Sinise (left) and John Malkovich in the 1993 film Of Mice and Men.

I was.

You directed the actors?

I did.

Is that the best of both worlds? A writer who gets to deal with the performances but doesn't have to deal with the technical stuff?

That's the only way I could do it. I would never want to direct a film completely. Too much time is consumed.

How do you work with actors? What do you say to them?

First of all, I try to pick actors that speak the same language as I do. I'm not didactic about that. There are certain actors who don't know anything about the Method yet are wonderful actors. They have instincts. I try to create an atmosphere of trust, so actors don't feel they are being judged, and so they can experiment and try things. I kind of edit for them and talk over problems that they may be having, see if I can find solutions that are helpful to them. That's really how I do it. I know too well ever to insist on someone doing it only one way. I welcome what the actor can bring. Five different actors are going to do the same scene differently. That I welcome.

Do actors recognize that you are writing in the 'beat'?

I don't talk about it. But I think that's why actors like my work. Mostly, too, because they love the subtext of it.

You've worked with Robert Duvall several times. What does he mean to you as an actor?

Oh, my lord. He's kind of my talisman. I just depend on Robert. So many times I've turned to him, and I just know whatever he does is going to be wonderful. He brings total commitment to the character he is playing and great integrity to his work.

Can you tell me a little about your history with him?

He was doing a play of mine called The Midnight Caller [in Sanford Meisner's acting class], and Sandy Meisner called me up and said, "Get on down here and see this young man in your play, because I think you'll be very pleased." Robert Mulligan was in town, and his then wife, Kim Stanley, was also around. My wife and I went down with them to see this production and were just taken with this young man playing a young alcoholic who totally disintegrated during the play and finally killed himself, though you never saw that—you just heard the character had done that.

When we were casting Mockingbird and thinking about who could play Boo Radley, my wife said, "What about that young man we saw?" Fortunately, Bob [Mulligan] had seen him also and said, "Yeah, you're perfectly right. Let's use him." That was the beginning. Then Robert was in The Chase, though I had little to do with it. Then we did this wonderful project called Tomorrow.

For my money, that's Duvall's best performance.

He's inclined to agree with you.

Robert Duvall (at left) and Gregory Peck (center) in To Kill a Mockingbird.

Even with The Godfather and Apocalypse, Now in the running.

Have you ever seen my film Convicts?

No.

You should see it. Because he's extraordinary in Convicts. Anyway, Robert and I did Tomorrow first as a play, then as an independent film. Then came Tender Mercies and then Convicts.

You don't talk very much about your other sixties screen credits: The Chase, Baby, the Rain Must Fall, and Hurry, Sundown . . .

The Chase is simply based on my novel.[*]

I thought you did a little consultation on the film.

Just before they went into production. But the film is so far away from my original work that I never thought it had much to do with me.

Did you talk about the script with Lillian Hellman?

No, Sam Spiegel. Lillian was, by that time, away.

Did they incorporate any of your ideas?

* The Chase was based on Foote's 1956 novel of the same name (New York: Rinehart), which, in turn, is an adaptation of his 1952 play.

I don't really know. I hope so. I only saw it once. I'm not fond of it at all.

How about Baby, the Rain Must Fall?

Baby, the Rain Must Fall I'm very proud of. I worked very closely with Alan Pakula and Bob Mulligan on that, and they shot it here in my home—in Texas. I was very much involved and on the set during the filming. Always with them—they're very inclusive.

What about Hurry, Sundown?

Not a word of it is mine. I got along very well with Otto [Preminger], but we just didn't agree on how it should be done. We parted amicably, and he got another writer and had a whole new script written that I've never read or seen. But Otto called me afterwards and asked if, as a favor to him, I would lie and put my name on the script. Since he'd paid me so much money, I felt I couldn't turn him down; so I said yes.

Are you certain not a word of it is yours?

Oh, I know because Otto told me.

Is that the reason why you worked on films only sporadically for a time? Because you had had these unpleasant experiences?

I didn't like working on big films, and so I had to wait until I could find a venue that was more acceptable to me. I liked working on Mockingbird and Baby, the Rain Must Fall a lot, but they were very personal films, and I just didn't like working on the impersonal, big-budget stuff.

It was Tomorrow that really turned me around. That was done for about $400,000, and there again, I felt very necessary and wanted. I was on the set and in the editing room, and that's how I felt it should be with a writer.

Wasn't there a period in the early seventies when you went to the New Hampshire woods and stopped writing?

No, I didn't really stop writing. There was a period in the early seventies when I went to the New Hampshire woods to reevaluate my work, but I wrote a great deal while I was there. I was discouraged because I didn't really have much in common with what I felt was going on in the sixties in the theater. I wasn't terribly interested in taking off my clothes or the kind of profanity that people felt was very liberating. I was interested in it, but I didn't feel a part of it. I felt I had to get away and work, because the other is very distracting: if you're around when everybody is saying, "This is the way to do it . . . this is what's selling . . . blah, blah, blah." I've been through so many different fashions now in theater and writing.

How did you come to write Tender Mercies. That was a rare, original screenplay for you. Was that written with Robert Duvall in mind?

No, I don't ever write with people in mind, although very soon after it was finished, I knew it was right for Bob. I was working on my Orphans' Home Cycle, as a matter of fact working on Night Seasons and a number of other things. I was living in New Hampshire, and I needed some money. My agent, Lucy Kroll, told me, "They like you out in Hollywood. You're so peculiar—

you won't pitch—but if you would just give me a few lines about something, I could get you some money to write it and to finish these other projects."

I thought about it. I was very interested in my nephew who was part of a group that had been playing around for gigs, as they call them, and the life of musicians reminded me much of what I had gone through as an actor. Most of the group had jobs on the side, and they would sometimes go to play at places where somebody—maybe the manager—had hired two orchestras for the same night, but the first one that showed up got the job. I began to think about a country-western band, paralleling it to my experiences as an actor—that kind of rejection. I told this idea to someone at 20th Century-Fox and she rather liked it and she told me that her boss was coming in from Hollywood. His name was Gareth Wigan, a partner with Alan Ladd, and would I tell it to him?

I thought that was easy enough, so I told it to him. He liked it but said, "There's only one thing. I think somewhere in there there should be an older character." I said, "Okay—I'll think about it." He said, "But I want to make a deal with you. When your agent comes out [to Hollywood], have her come round, and we'll work out a contract."

Out Lucy [Kroll] went. She got off the plane, bought the Reporter or Variety, and the first thing she read was that Wigan and Ladd had left Fox.[*] In the meantime, I had been thinking about the idea, as is my wont. I got intrigued, and because I really don't like to accept money before things are written, I thought I'd just pull in my belt and write it. I did and felt it was a wonderful part for Duvall; so I called him up, and we met in New York at a place I was subletting. I read it to him, and he said he'd do it.

It wasn't all that easy to get it done. It took us almost two years. A man named Philip S. Hobel and his wife, Mary-Ann Hobel, were very helpful as producers; then of course [the director] Bruce Beresford was a great gift to us. I had seen Breaker Morant —which I loved and still love as a film—but I didn't think he would be interested in this at all. In the meantime, we'd been turned down by many directors. Bruce was sent the script in Australia. He told me he usually waits a month before reading a script, but something told him to go to this one right away, so he read it. Halfway through it, he called up and said he'd do it. He said, "I just have to know one thin—if I can get along with the writer." And we got along very well.

Did he change it much?

Not much. The essence of it was always there. I think maybe there was some narration that he felt was unnecessary—things like that. He edited more than changed.

* Twentieth Century-Fox President Alan Ladd, Senior Vice President Jay Kanter, and Vice President Gareth Wigan announced in June 1980 that they would resign from the studio as of December 1980.

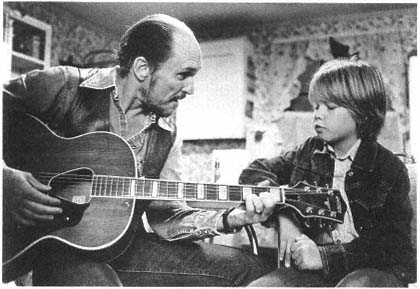

Robert Duvall and Allan Hubbard in Tender Mercies , directed by Bruce Beresford.

What about Duvall? Did he do any writing on the set?

When he was working out scenes, there were things he did that I incorporated into the film.

The title Tender Mercies comes from the Seventy-ninth Psalm.[*]

It's from a lot of psalms, actually, but it's also from the Seventy-ninth.

How did you settle on that title?

I don't know. I just love the phrase.

It's often said that a writer has about three stories in him, and that he spends a lot of time rewriting or revising them in various guises. It may or may not be true. What do you think about that?

Thematically, if you're talking about themes, I think themes do reappear constantly in one's work. I thought what Ben Brantley said about Night Seasons was very perceptive,[**] and I'm going to write him a little note and thank

* Psalms 79:8: "Let thy tender mercies speedily . . . "

** HortonFoote also directed Night Seasons, which starred his daughter, the actress Hallie Foote, as Laura Lee Weems, "a small-town, family-smothered spinster." Ben Brantley wrote in the New York Times (November 7, 1994) that "father and daughter conspire to present a lucid anatomy of a subject that has always obsessed the author: the elusiveness of the idea of home The theme has echoed plaintively throughout Mr. Foote's oeuvre, from his best-known work, A Trip to Bountiful, to his nine-play 'Orphans' Home Cycle.'"

him for it. He spoke about the theme of home reappearing in my works, and how it surfaces and was worked out in Night Seasons, and that's true. I know it does reappear all the time. It's almost an irony in the sense that [the character of] Josie lives in this apartment and can't even remember names anymore; Laura Lee, all she has are pictures of houses that she pastes into a scrapbook; and Thurman and Delia, who get a house, it's hell for them—because they fight all the time—home has no meaning for them at all. In that sense, it's a very ironical use of the desire for home.

You're often said to have an affinity with Faulkner—perhaps because of York County and Harrison, Texas—and people also compare you to Chekhov. But in our conversations, you have mentioned Flannery O 'Connor, Katherine Anne Porter, Reynolds Price, Eudora Welty.

Peter Taylor is another. I haven't mentioned him yet. Now I will, because he's been an influence on me, and another important influence is Elizabeth Bishop.

Really?

Oh, yeah. I read her all the time. Marianne Moore, T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound—they also had an enormous influence on me. Faulkner? I admire him greatly, and I've adapted him; as a matter of fact, there's another Faulkner project that may come about, an adaptation of The Old Man which I first did forty years ago for Playhouse 90.

That's also where Tomorrow started.

That's right. There's talk now of reviving The Old Man as a film, which I would love to do. I have a great affinity for Faulkner. I know stylewise I have learned much more from Katherine Anne [Porter] or Elizabeth Bishop, however. In other words, I'm a taker-outer rather than a putter-inner.

How so?

I'm not a minimalist—I don't mean that. But I like to eliminate. Faulkner, I think, is a grand master of the rolling phrase and the long sentences. I don't know how to do that.

Now, Chekhov? I adore Chekhov's short stories very, very much, and I love his plays—no question about it—but in some ways, I feel closer to his short stories. He was a great short story writer. Of course, he is a great playwright.

How does a play occur to you?

Boy, if I knew that—if I could patent that—I'd be a rich man. All kinds of devious ways.

Do you still take long walks to stimulate the writing?

Yes, I also keep notebooks, and sometimes just a phrase in a notebook will start me off. I never know. I've also learned that you can't really predict the time for the consolidation of the idea. You can use your will, and you can say, "I know this is wonderful—I'm going to make it work," and it just won't do it. Something is larger there, and you have to say, "Okay, you win." Katherine

Anne Porter has that theory about the drawer: you put something in a drawer, and when you go back to it, something has happened to it. Sometimes something bad happens to it.

Could you write a play that is set in New York City?

I could try. I don't guarantee what would happen. I don't hear it. Lord knows I've spent a lot of my life here, and I keep thinking to myself, "I really would like to write a play about the theater." Maybe I will. I just don't, instinctively. Other themes are somewhere in there (points ), and they keep resurfacing—knocking, knocking—saying, "Let's go."

You can't push it or force it, call or bend it to your will.

No, you can't.

But the fact of the matter is, you've written a score of television plays—by now, thirty or so—you've written screenplays—

Yes, I work all the time. All I'm saying is—

Do you have all these different projects going at different times in different drawers?

Sometimes I do. One might run out of fuel; then you just take up something else. It's a very mysterious thing—writing. It's like acting: You can study techniques until you drop over on your face. Then there's the x factor. It's not fair, because I know the most wonderful, the hardest-working people in the world that are actors. They know all the technical things, but nothing much happens. The same with many writers that I know. But with certain writers, their talent is the essence of the person. It's something that's uniquely theirs. It's—

Grace?

Grace, maybe. It's like the palm of your hand. It's your voice. You can pick up certain stories and know immediately who wrote that story after three or four paragraphs. I don't think that can be taught, and I don't know where that comes from. It's one of the great mysteries, as far as I'm concerned.

Did you always have the same voice? Can you discern periods in your work?

I can, but I can tell you that the root is always there. The preoccupations are always there. The search is always there. Sometimes it's done better than other times, and I hope and trust I've learned something through the years, although there are certain of my early things that I'm very impressed with. Some of it I don't think I could do today.

Do you, after all these years, think of yourself principally as a playwright?

I am first and foremost a playwright. I don't mean that to be quite as dismissive as the way it sounds. I really would hate to give up screenwriting. There was a time when I would just tell you right off: I'm a playwright—and that's it. But I've learned from being a screenwriter. I think I've learned, although I'm discouraged right now. Because the way I like to do films is to

do independent films. I'm not a big studio man; I just don't operate well with them. Therefore, I'm not aggressive about films. I have three films in different stages of progress right now. But they're all very hard to sell and hard to do.

One of them Duvall wants to do, if he can get it off the ground, and I hope he will, called "Alone." Then I was commissioned by Eddie Murphy's company to write a film about blacks, which I'm very proud of. And Bruce Beresford is dying to direct that one. It's called "The Man of the House." They're trying to find a studio to finance it right now, because Murphy himself won't be in it.

The third project is called "The Parson's Son." It's an original, but I was paid to write it by a company called Wind Dancer. It would be their first feature film. Mostly they've done television—Home Improvement and The Cosby Show, for years. Again, it's a very unorthodox story. The other two are Harrison; this one is outside Harrison. They had sent me a short story to dramatize; I liked the story, but I didn't feel it could be a film. When I met with the author, I learned he is a third-generation Lutheran minister—and I got very interested in him. That's literally what the film is about—his history and his personal story, and what it meant to grow up as the son of a Lutheran minister.

Whatever happened to your Bessie Smith project?

Someone could do my Bessie Smith script right now, if they felt they could do it for $12 million, but Bruce [Beresford] feels it has to have at least $18 million, and nobody can get that much money for it.

This is a script you wrote—

Many years ago. It was written for Columbia Pictures. [The choreographerdirector] Joe Layton wanted to do it; then Columbia backed away because musicals—particularly black musicals—weren't considered commercial. So I didn't own the rights for a long time, but I have a copy here, and one of my sons, who wants to be a producer, was rooting around, looking for material, and he pulled out "Bessie" and loved it. I said, "You picked the wrong thing— because I don't own it." But he was very aggressive about it and found the money to buy the script back.

Didn't the producers of Driving Miss Daisy want to do it at one time?

Yes. Very badly. But their budget was $28 million.

Is your work on all of these unproduced screenplays finished?

My work is done. When it gets closer to production, maybe there will be things to do, but my work is done.