4

Valuables and Prestations

Trade and Prestation

Melanesians have been represented as preoccupied with the exchange of material goods.[1] In many instances the stereotype is undeserved and serves to mask a fuller understanding of the nature and meaning of transactions. Nonetheless, many ethnographers have pointed to broad distinctions between classes of transactions involving material items, variously contrasting trade, barter, commodity exchange, or "economic exchange" with ceremonial exchange, prestation, or gift. Others have made such distinctions from more theoretical perspectives (e.g., Gregory 1982; Sahlins 1972).

The passage of goods between parties to an exchange is one of innumerable forms of transaction as that notion may be broadly understood (Kapferer 1976). As I have argued in the Introduction, it is misleading to distinguish trade from prestations on the basis of descriptions of their conduct. This is an exercise in typologizing that must crumble in the face of intermediate cases. Rather, I argue that these forms of exchange should be distinguished in terms of actors' primary interests or intents. This is not to say that a label can be attached definitely to any particular transaction one may witness. Multiple social and cultural factors are involved in any transaction which are capable of manipulation and variable interpretation by the actors (cf. Bourdieu 1977).

This approach has the advantage of conforming to some theoretical arguments developed by Sahlins (1972), and also to the conceptions of the Maring themselves. The Maring make a terminological distinction between two general forms of exchange which I gloss as "trade" and "prestation." Each term entails an understanding of reciprocity, but the social and material contexts of the exchanges may vary widely. The term munggoi rigima , literally "valuables exchange," which I translate as "trade," refers to transactions explicitly concerned with the acquisition and distribution of goods. As stated by informants, the overt focus of such transactions is on the reciprocal movement of dissimilar objects of value. Trade transactions may occur between individuals— never groups—standing in any relationship to one another.

The term munggoi awom , literally "valuables give," I translate as "prestations" or "gifts." In these transactions the participants are explicitly concerned with the establishment, continuation, or discharge of social relations, rights, and obligations. The flow of material objects is not necessarily reciprocal but may entail the transmission of valuables in exchange for the gift of a woman in marriage, military aid, or settlement of insult. Maring exegesis points to the more restricted nature of munggoi awom exchanges: they occur only between particular categories of persons or collectivities in certain circumstances.

As a consequence of these different orientations of modes of exchange, the interests of transactors shifts from the appearance of a dominant concern for objects and the self in trade to a concern for the other in prestations. I say "appearance" of material self-interest since, in the final chapter, I argue that in the praxis of trade there is a potential for the expression of a central concern for sociability. Further, although the Maring characterize trade as centered on objects, it would be a misleading oversimplification to treat it as an essentially materialistic pursuit. It is also important to note that, in the absence of overt haggling or bargaining, trade does not involve competition within or between groups of "buyers" and "sellers," nor is it geared to the making of profit (cf. e.g., Thurnwald 1932). These issues can only be noted here but will be dealt with further in later chapters.

Trade transactions tend to be unremarkable events, involving only a pair of individuals. The actual exchange of goods is a relatively private event, unencumbered by elaborate codes of conduct. They are therefore hard to see, and many ethnographers whose attention was focused elsewhere may have gained the false impression that trade is of little significance. Prestations, by contrast, run the whole gamut from

the commonplace, private exchange of minor valuables between individuals as a sign of courtesy or intimacy to the rare and glorious spectacle of the dances and distribution of salted pork to allies in the final stages of the konj kaiko ceremony.

The various forms of prestations in fact can be grouped into two broad classes that I gloss as major and minor prestations. There is no general term for major prestations. Usually, they are highly public events involving groups of transactors. They consist of several named categories of ceremonialized exchange to mark specific events in the life cycle of individuals or the fortunes of collectivities. Such transactions usually involve strict codes of conduct relating to participants and the appropriate nature and quantities of goods. The various kinds of major prestations are detailed below, but examples include bridewealth and death payments. Minor prestations or gifts are known collectively as munggoi aure awom ("valuables nothing give"). The various forms and circumstances are not named. They are unceremonialized exchanges, usually between individuals, expressing solidarity, reconciliation, or intimacy attending numerous social events for which no named ceremonial exchange is obligatory. There is no set code of conduct relating to the occasions when gifts are appropriate, or to the kind and quantity of goods involved. Examples include mutual gifts between visiting matrikin or affines, or small prestations as expressions of sympathy in times of misfortune or as appreciation of past kindness.

There may be some objection to collapsing into a simple dichotomy the variety of transactions empirically present among the Maring and others (for which both the participants and anthropologist can provide distinctive labels). Mauss (1954: 28-29) provides some justification for such an exercise implicit in his complaint of the proliferation of Trobriand terms for different kinds of prestations, which masks the common features of all forms of the "gift."

To characterize trade as primarily "economic" in focus and prestations as social, political, or religious in orientation is misleading.[2] Clearly, both forms of exchange have important economic implications for the production of exchangeable items, their distribution, and consumption. A trader, nonetheless, may be motivated by a desire to acquire a particular item that he can use in a social and political transaction, such as bridewealth in exchange for rights to a woman's productive and reproductive powers and the political support of her agnates, or a religious transaction, such as the sacrifice of a pig to the spirits in exchange for health and protection. Even trade transactions

with an apparently self-interested and materialist, "economic" focus may also involve strong social and political motives. For instance, trade between affines may be pursued partly because the transaction has some utilitarian benefit for the participants, but also because it expresses a commitment to maintain their social and political links. By the same token, parties to a prestation may be conscious of the practical utility of the exchange as a means of redistributing useful or desirable goods.

These considerations indicate that trade and prestations as pure forms occupy the poles of a continuum and that they intergrade in some intermediate region. I stress that the distinctions, which derive from a particular ethnographic context, lie in actors' perceptions or interpretations of particular events and motives. The labeling of any specific transaction therefore cannot be based on mere observation by the ethnographer but requires attention to transactors' evaluations of their activities. This scheme thus serves as an advance on a similar continuum of forms of exchange proposed by Sahlins (1972) in terms of generalized through balanced to negative reciprocity, in which a priori assumptions about kinship distance are held as important determinants or covariants of the form and conduct of transactions. In Sahlins's scheme, what I call prestations fall toward the generalized reciprocity pole, typically involving relatives, and trade transactions toward the negative reciprocity end typified by self-interested, potentially hostile relations between unrelated persons.

Maring prestations occur between kin and affines, but parties to trade transactions run the spectrum from unrelated strangers to close relatives—even true brothers—and transactions may be completed immediately or delayed for up to several years. The conduct of trade transactions will be examined in chapter 8. Here I wish merely to note that although trade and prestations may be difficult to disentangle theoretically, to the Kundagai the distinctions in practice are clear, and must be so, if they are to react appropriately by normative standards in any particular transaction. Of the several thousand cases of exchanges that I collected, my informants were nearly always quite certain whether any one was to be understood as munggoi rigima or munggoi awom .

Since the goods and persons involved in Maring prestations are also those engaged in trade, neither form of exchange can be examined in isolation. Both are forms of the distribution of goods and of intergroup relations. Although the focus of this study is on trade, it becomes obvi-

ous from the foregoing remarks that one cannot understand the movement of goods in trade in isolation. The last chapter showed how the production of plumes destined for trade is embedded in the relations between humans and the environment, between groups and individuals, and between humans and the spirit world. Here I identify the major goods involved in trade and prestations, their ownership, and the flow of goods in prestations, before making a detailed examination of trade in subsequent chapters.

Valuables

In common with many other New Guinea societies the Maring class a range of goods in a named category, munggoi . The term has two meanings. In a general sense it refers to any object that is described in Tok Pisin as samting pulim pe , something that "pulls pay" or has exchange value. In this sense it may refer to any good passed in trade or major and minor prestations. In a more restricted or focused sense it is confined to "valuables" or "prestige goods." Paradigmatically, valuables in this narrow sense embrace items passed in major prestations: pigs, cassowaries, certain shells, stone and now steel tools, and paper money. Some high-value bird plumes and marsupial skins are also classed as munggoi in this restricted sense, although they are not used in major prestations among the western Maring. The Kundagai explain that they are "valuables" because they are of comparable exchange value to pigs, the preeminent object of ceremonial exchanges. Indeed, many such plumes and skins are used to acquire by trade pigs later killed for prestations. In all, some thirty-six objects fall into the category of "valuables" (although some informants are inclined to expand the list). Only twelve of these, however, are valuables in the restricted sense and are or were regularly employed in major ceremonial exchanges, and only munggoi are so used. Although traditionally the western Maring, including the Kundagai, did not use plumes in major prestations, the eastern Maring and the Narak and Kandawo have always done so. The Kundagai, however, have recently received some Red Bird of Paradise, Hornbill, and Paradise Kingfisher feathers in bridewealth, mainly from eastern Maring communities, although they do not include feathers in any major prestations they make.

The category munggoi as valuables includes items that may also be used as decorations, mokiang , but not all mokiang are also valuables. Many non-munggoi decorations are also traded, though less commonly

than are munggoi and generally at lower exchange rates. There is no doubt that the introduction of money has facilitated trade in these lesser goods and that, although some of these goods were formerly obtained by the Kundagai from beyond their territory, this was mainly in minor prestations from kinsmen rather than by trade. A few items are neither munggoi nor mokiang and are occasionally exchanged for money; these, however, were probably seldom if ever traded in the past.

Appendix 3 gives details of over seventy goods transferred in trade. The catalogue of items actually traded in any one period of time has varied as indicated in the appendix. Most things no longer traded are not used for any other purpose, such as decorations, or even retained as mementos of the past. For instance, to my knowledge no Kundagai now owns a dog-tooth necklace or pack of native salt.

Over one hundred items, animal, vegetable, and mineral, provide decorations, but I recorded only forty-seven used in trade. Of the fifty-three species of birds used in decorations, twenty-seven are or have been traded.

Goods passed in trade can be classed broadly either as more or less ubiquitous or as specialized and localized in origin. Here I classify goods relative to their availability in Tsuwenkai. Items found in both Tsuwenkai and many other areas of dissimilar environment are not of specialized origin. Things found only in Tsuwenkai or a limited number of other similar environments, or widely distributed goods absent from Tsuwenkai, are classed as being of specialized origins. By this reckoning twenty-three, or somewhat less than half of the items ever traded, are the products of ecologically or technologically distinct areas. In most cases items are peculiar to high or low altitudes, although salt, stone, and some pigments are derived from localized deposits that are distributed with little relation to altitude.

The Maring grade valuables into broad hierarchic categories of order of value. Unlike, for instance, the Mae Enga (Meggitt 1971: 200), the Maring hierarchy does not involve rigid restrictions on the interconvertibility of items of different hierarchic levels. The Kundagai say that ideally items of one level can be exchanged for those in any other level. Mae Enga valuables normatively can be exchanged only with items of the same or immediately adjacent levels. Nonetheless, on the one hand, exchanges of goods with widely divergent value would not be contemplated by the Maring. On the other hand, convertibility. between Maring levels is enhanced insofar as items within any one level

are not of equal exchange value. The levels of value therefore do not conform to a scale of exchange value but are, rather, a hierarchy of "worth or desirability" (Meggitt 1971: 199).

Scales of value have altered over time as items available for use in prestations have changed. Table 13 lists hierarchies of valuables around the year 1900 (as related by an old man born around that time) and in the present. Opinion varies somewhat as to the number of levels and the allocation of specific items in the contemporary hierarchy.

Some informants list money in the same category as pigs, shells, and steel tools, because, like those items, it is a major component of prestations. Those who place money in a separate category of superior value do so because they say that since money can be converted to any other item more freely than other valuables it is the most valuable. It is therefore the most desirable of all goods.

Other categories crosscut these hierarchies: all shells are glossed mengr , bird plumes as kabang an (feathers) or kabang wak (skins), and marsupial fur as koi-ma an and skins as koi-ma wak .

Ethnographers frequently record quantities of valuables transferred in ceremonial exchanges. Except for pigs, however, there are few published details available on valuables stocks retained by individuals. A major aim of the following discussion is thus to document patterns of ownership of valuables among the Kundagai and show how the means of acquiring valuables varies. It must be conceded immediately that custodianship of valuables does not necessarily mean ownership, as one may hold temporary stewardship over, say, shells that belong to others. Nonetheless, the great bulk of valuables I saw during a census of valuables collections were identified by their custodians as their personal property.

I did not discern any reluctance on the part of the Kundagai to show me their plume and shell collections. It is possible that some men had stored separately shells that they had received in, or were about to give in, prestations, and that they preferred to keep the fact secret from my assistants and spectators in case their display should provoke claims or comments. In the absence of signs of evasiveness, however, I am confident that I saw most shells and plumes owned by resident Kundagai. I also saw some valuables belonging to absentees which were stored with resident kinsmen. In their general willingness to display and discuss valuables collections the Kundagai dearly contrast with some other societies—such as the Mae Enga, at least in respect of pigs (Meggitt 1974)—where such information is sensitive and secret.

TABLE 13. | ||||

Order of Value | Items | |||

A. ABOUT 1900 | ||||

1. | Greensnail shells | |||

2. | Pigs, live cassowaries, plumes of Astrapia, Sicklebill, Superb and Saxony Birds of Paradise, Vulturine Parrot, Fairy Lory, Goura Pigeon, Hornbill and Buzzarda | |||

3. | Stone axes | |||

4. | Dog- and marsupial-tooth necklaces | |||

5. | Nonema bead necklaces | |||

6. | Marsupial tails and pelts | |||

7. | Job's Tears necklaces | |||

B. IN 1973-1974 | ||||

1. | Money | |||

2. | Pigs, cassowaries, kina and greensnail shells, steel tools | |||

3. | Plumes of Astrapia, Sicklebill, Lesser, Superb, Saxony, and Raggiana Birds of Paradise, Vulturine Parrot, Papuan Lory, Cockatoo, Paradise Kingfisher, Hornbill, Buzzard, and Harpy Eagle; marsupial skins | |||

4. | Loose fur, chickens, minor shells | |||

a Other plumes, for example, of the Lesser Bird of Paradise, probably fell in this level. | ||||

As noted in chapter 2, most plumes and furs are owned by younger men, as it is they who more keenly participate in dances. Plumes and skins are not used by the Kundagai and other western Maring in major prestations, so that older men who are uninterested in dancing do not generally retain such goods except as trade items. In table 14 I give details of how animal remains recorded in the census of valuables were acquired.

The most common means of acquiring plumes and marsupial skins retained in valuables collections was by gift, followed by trade. By "gift" I mean minor prestations as outlined above. All the marsupial skins listed in the table are low-altitude species unavailable to Tsuwenkai Kundagai hunters by virtue of territorial hunting rights. Concerning bird plumes, trade and loans are more important means of acquiring valuable, or munggoi , plumes than those regarded only as decorations. This is as one might expect, for munggoi items, being more desirable, are more likely to be sought by a trader than are non-munggoi , as they can be used not only for decorations but exchanged for other valuables. In other words, they become commodities as well as decorations and, as such, can be converted into other desirable items. Non-munggoi

TABLE 14. | ||||

Total No. sets | Trade | Loan | Shot | Found |

A. BIRD PLUMES | ||||

All Species | ||||

458 | 120(26.2)b | 14(3.1) | 122(26.6) | 31(6.8) |

Non-valuables | ||||

187 | 29(15.5) | 1 (0.5) | 69(36.9) | 12(6.4) |

Valuables | ||||

271 | 91(33.6) | 13(4.8) | 53(19.6) | 19(7.0) |

B. MARSUPIAL SKINS | ||||

45 | 20(44.4) | 2(4.4) | ||

C. BEETLE SHARDS | ||||

17 | 5(29.4) | 7(41.2c ) | ||

a Refers exclusively to minor prestations. | ||||

b Numbers in parentheses are percentages of row totals. | ||||

c Collected by present owners in swarming season. | ||||

goods do not enjoy such free exchangeability. Gift is almost as important a means of acquiring munggoi as non-munggoi plumes, but hunting is of relatively minor importance in acquiring munggoi plumes, though in large part this is because six of the fifteen munggoi species are not found in Tsuwenkai.

The pattern of acquisition of shells differs from that of other animal products. Partly this is because shells are not of local origin and also because their uses and the categories of men owning them differ. Shells are transferred in large numbers in major prestations in which older men participate. Tables 15 and 16 give details of the ownership of 210 kina and 250 greensnail shells recorded in the collections of all 55 resident adult males. I have not reordered data on the distribution of ownership by age for other shells, as the numbers recorded are small and these shells are now very rarely used in prestations. Gross holdings of these other shells were as follows: 28 sets of Nassa dogwhelk headbands and ropes, most acquired in bridewealth, 3 sets of Cypraea cowry ropes, 8 Conus shell disks, mostly obtained in gifts, and one Melo bailer-shell fragment, acquired in bridewealth.

TABLE 15. | |||||||

Age: | 15-25 | 25-35 | 35-45 | 45-55 | 55-65 | 65-75 | All ages |

Number of men: | 7a | 22b | 11c | 5c | 7d | 3e | 55 |

A. KINA | |||||||

No. men owning | 2 | 21 | 9 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 43 |

No. shells | 6 | 111 | 45 | 21 | 23 | 4 | 210 |

Range owned | 0-4 | 0-13 | 0-9 | 1-8 | 0-14 | 0-3 | 0-14 |

Av./total men | 0.8 | 5.0 | 4.1 | 4,2 | 3.3 | 1,3 | 3.8 |

Av./men owning | 3.0 | 5.3 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 2,0 | 4.9 |

B. GREENSNAIL | |||||||

No. men owning | 3 | 17 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 42 |

No. shells | 28 | 109 | 59 | 19 | 24 | 11 | 250 |

Range owned | 0-15 | 0-13 | 3-12 | 3-6 | 0-16 | 0-7 | 0-15 |

Av./total men | 4.0 | 5.0 | 5,4 | 3.8 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 4,5 |

Av./men owning | 9.3 | 6.4 | 5.4 | 3.8 | 6.0 | 5.5 | 5.9 |

C. KINA AND GREENSNAIL COMBINED | |||||||

No. men owning | 3 | 22 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 47 |

No. shells | 34 | 220 | 104 | 40 | 47 | 15 | 460 |

Range owned | 0-19 | 1-25 | 3-17 | 5-11 | 0-30 | 0-10 | 0-30 |

Av./total men | 4.9 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 8.0 | 6.7 | 5.0 | 8.4 |

Av./men owning | 11.3 | 10.0 | 9.4 | 8.0 | 11.7 | 7.5 | 9.8 |

a Only one of these men is married; he and two others owned all the shells. | |||||||

b Four of these men are unmarried. | |||||||

c All men have at least one living wife. | |||||||

d Includes two widowers. | |||||||

e Only one man with surviving wife. | |||||||

Although plumes and skins are retained primarily for use in decorations or trade, shells are required as major components of prestations. They are also commonly traded but are only minor items of decoration. Consonant with these different social utilities, patterns of ownership and means of acquiring shells differ by age groups from holdings of plumes and skins.

In general one might anticipate that young and old men will own fewer shells as they will tend to be less involved in ceremonial payments, requiring fewer shells for prestations and receiving less. Young unmarried men are not considered to be fully adult, partly because they have not assumed responsibilities for dependents and for the maintenance of amicable relations with affines. As such their need of shell valuables is not great. Old men similarly are often little involved in

TABLE 16. | |||||||||||

Means of Acquisitionb | |||||||||||

Age | No. owninga | No. shellsa | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |

A. KINA | |||||||||||

15-25 | 2 | 6 | 3(50.0c | 1(16.6) | 4(66.6) | 1(16.6) | 1(16.6) | ||||

25-35 | 21 | 83 | 16(19.3) | 10(12.1) | 25(30.1) | 3(3.6) | 5(6.0) | 5 9(71.1) | 20(24.1) | 4(4.8) | |

35-45 | 9 | 41 | 11(26.8) | 4(9.8) | 13(31.7) | 6(14.6) | 1(2.4) | 35(85.4) | 6(14.6) | ||

45-55 | 5 | 12 | 7(58.3) | 1(8.3) | 2(16.7) | 1(8.3) | 11(91.7) | 1(8.3) | |||

55-65 | 4 | 23 | 16(69.6) | 2(8.7) | 2(8.7) | 20(87.0) | 3(13.0) | ||||

65-75 | 2 | 4 | 3(75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 4(100.0) | ||||||

B. GREENSNAIL | |||||||||||

15-25 | 3 | 28 | 4(14.3) | 8(28.6) | 12(42.9) | 14(50.0) | 2(7.1) | ||||

25-35 | 17 | 84 | 19(22.6) | 6(7.1) | 21(25.0) | 3(3.6) | 8(9.5) | 57(67.9) | 19(22.6) | 8(9.5) | |

35-45 | 11 | 58 | 20(34.5) | 6(10.3) | 14(24.1) | 3(5.2) | 8(13.8) | 51(87.9) | 7(12.1) | ||

45-55 | 5 | 16 | 5(31.3) | 3(18.7) | 1(6.3) | 3(18.7) | 12(75.0) | 4(25.0) | |||

55-65 | 4 | 24 | 11(45.8) | 2(8.3) | 1(4.2) | 14(58.3) | 10{41.7) | ||||

65-75 | 2 | 11 | 3(27.2) | 2(18.2) | 3(27.2) | 8(72.7) | 3(27.2) | ||||

C. KINA a GREENSNAIL COMBINED | |||||||||||

15-25 | 3 | 34 | 7(20.6) | 8(23.5) | 1(2.9) | 16(47.1) | 15(44.1) | 3(8.8) | |||

25-35 | 21 | 167 | 35(21.0) | 16(9.6) | 46(27.5) | 6(3.6) | 13(7.8) | 116(69.5) | 39(23.3) | 12(7.2) | |

35-45 | 11 | 99 | 31(31.3) | 10(10.1) | 27(27.3) | 9(9.1) | 9(9.1) | 86(88.9) | 13(13.1) | ||

45-55 | 5 | 28 | 12(42.9) | 4(14.3) | 1(3.6) | 5(17.8) | 1(3.6) | 23(82.1) | 5(17.8) | ||

55-65 | 4 | 47 | 27(57.4) | 2(4.3) | 4(8.5) | 1(2.1) | 34(72.3) | 13(27.7) | |||

65-75 | 2 | 15 | 6(40.0) | 2(13.3) | 1(6.7) | 3(20.O) | 12(80.0) | 3(20.0) | |||

TOTALS | 46 | 390 | 118(30.3) | 34(8.7) | 87(22.3) | 20(5.1) | 28(7.2) | 287(73,6) | 88(22.6) | 15(3.8) | |

a Totals in these columns do not equal totals that can be calculated from table 15 since means of acquisition of some shells is unknown. | |||||||||||

b For explanation of categories see text. | |||||||||||

c Numbers in parentheses are percentages of row totals. | |||||||||||

prestations. In part this is the result of their declining interest and ability to participate through age and ill health, but also because sons.., on reaching middle age, assume the exchange responsibilities of their fathers. It follows that married men of middle age can be expected to be most involved with prestations and so to handle larger amounts of shells. This does not necessarily mean that they will hold larger stocks.

Data on shell holdings of fifty-five men are arranged in ten-year-interval age groups in tables 15 and 16. Some clarification of certain tabulated means of acquisition is required. Informants usually specified whether a shell was received in a major prestation—mainly bridewealth and death payment—or as a return gift for such a payment they had made or contributed to. In the first instance, shells were acquired directly from donors or indirectly in redistributions from major recipients. Return payments include three subcategories: direct returns for earlier major prestations by current shell owners; as indirect returns in redistributions from other major recipients; as returns for helping kinsmen make their own major prestations. That is, figures for bridewealth and death payments, and for returns for these two prestations, include shells both distributed between groups making prestations and redistributed within recipient and donor groups. The inclusion of several types of distribution under one heading conforms to Kundagai presentation of information. The "gift" column includes shells passed in minor prestations (munggoi aure awom ) that were not counted as reciprocation for aid in amassing prestations associated with marriage or death.

As suggested, the average number of shells owned by individuals in different age groups varies as does the relative importance of means of acquisition. Most shells are acquired in prestations, although relative proportions vary with age. Trade assumes greater significance as a source of shells for young and, to a lesser extent, old men, with prestations being most significant for men aged between thirty-five and fifty-five. The few shells listed as acquired by "other" means include several taken live from the sea, then cut and polished by their present owners while working on coastal plantations. One man also inherited nine shells from his father. Several dogwhelk collections had also been inherited. Inheritance of shells seems uncommon; on death a man's valuables are normally distributed to kinsmen as part of a death payment.

It is appropriate to note briefly how the age groups employed in the analysis relate to the developmental cycle of men and their households.

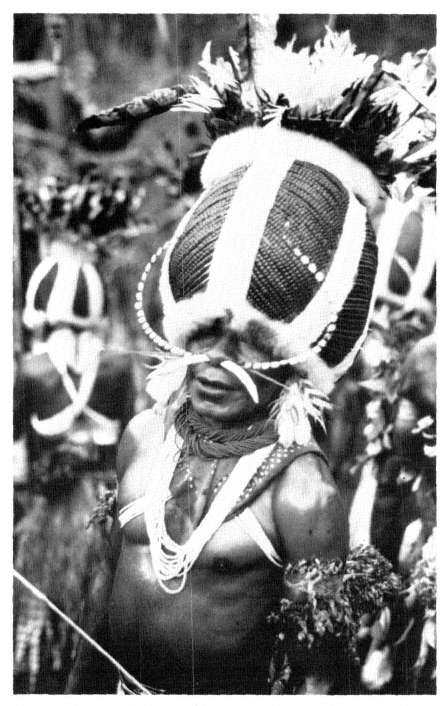

Lucien Yekwai in full dancing regalia. He wears a mamp ku glong wig, decorated

with lines of scarab beetle heads, cuscus fur strips, and plumes of eagle, fowl, and

parrot, and carries a bow in his left hand.

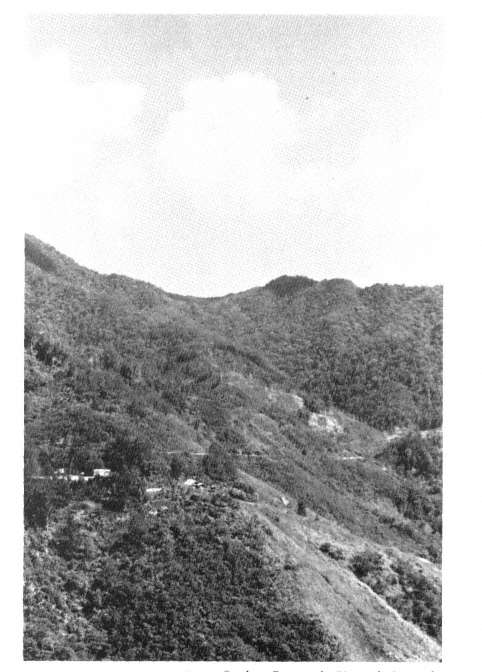

Looking north up the Kant Valley to Gendupa Pass on the Bismarck Crest. The

buildings on the nearer ridge include the ethnographer's house (center) and the

haus kiap (government rest house) located on the edge of the census ground (left).

Note the planted casuarina trees around the census ground, graded walking track

on flank of farther ridge. Newly cleared gardens can be seen at the forest edge at

the head of the valley where the Kant River turns sharply westward. Fallow growth

in the middle altitudes obscures several homestead sites.

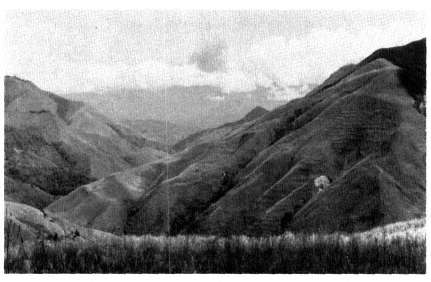

Looking south across the Pint Basin grasslands. The long ridge sloping down from

the right is the north face of Komongwai near the southern border of Tsuwenkai

territory. Kompiai settlement is located on the ridge to the left. The Sepik-Wahgi

Divide lies on the skyline. Note the landslip scar on the flanks of Komongwai and

horizontal marks attributed by the Kundagai to old garden terraces cleared in

grassland before the arrival of steel tools in the 1940s.

Mount Dundunk on the heavily forested Bismarck Crest, seen from a homestead

yard.

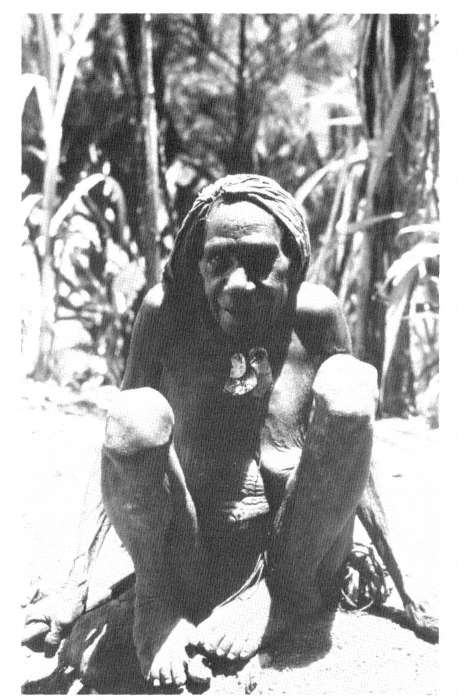

Kumbwamp in 1974, aged about 65. She wears a traditional bark cloth cape and

necklace of greensnail shell fragments.

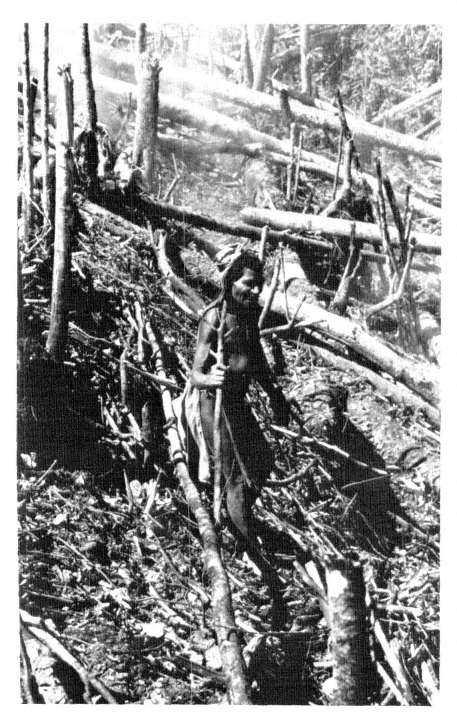

Wande planting a newly cleared garden cut from advanced secondary forest. Burnt

rubbish is still smoking in the background.

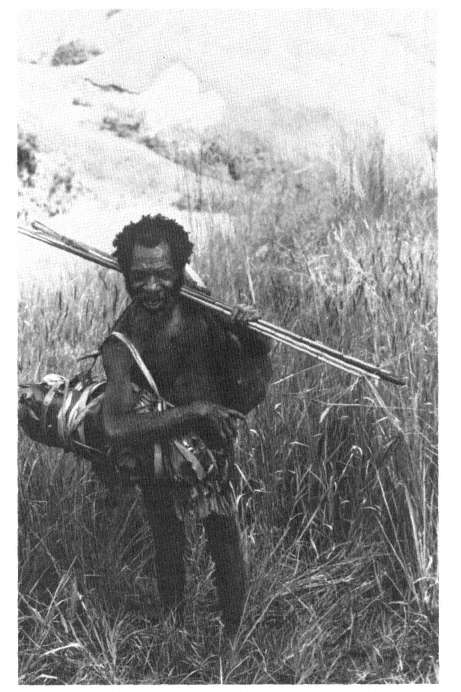

Kamkai returning home from work in his gardens. He carries harvested tubers and

other produce in a bilum (string bag) and improvised bundle carried in the male

fashion slung from the shoulder. Because he has been working in a bush area, he

carries a bow and hunting arrows in case he encounters game. He has hitched up

his apron for ease of movement in thick undergrowth.

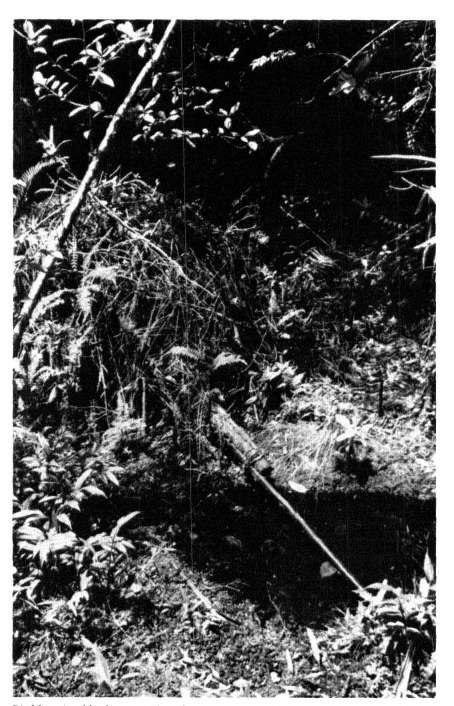

Bird hunting blind at a pool in the high altitude forest. The blind has been abandoned

for some time and is in disrepair, with its heavy leafy covering largely rotted

away revealing the domed structure. A bark tube to guide an arrow to its mark

protrudes through the blind wall bound to the top of the pole that serves as a

perch.

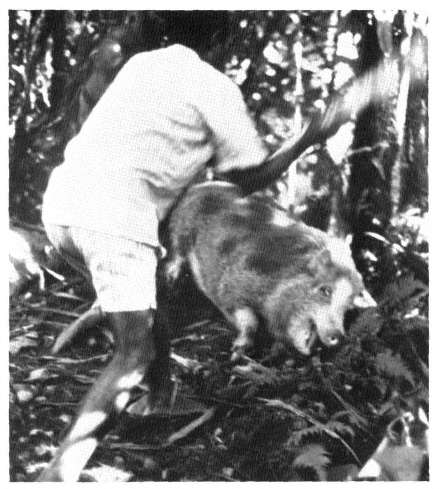

Sacrifice of a large pig for a bridewealth presentation in a raku , sacrificial grove

and cemetery.

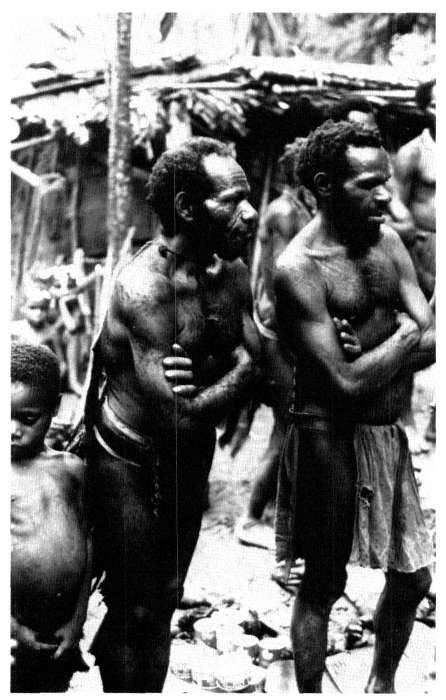

Spectators at a bridewealth presentation in 1974. The low, turtle backed house in

the background, roofed with pandanus fronds, is typical of Tsuwenkai houses.

Part of a bridewealth presentation on display, 1974. Greensnail shells are arranged

at the far end, kina, flanked by lines of paper money on the left (the arrows are

to prevent the money from blowing away, and are not part of the presentation),

axs and bushknives to the right. Joints of cooked pork are on display in a separate

pile out of the photo.

After presentation of bridewealth the bride and her companion emerge from se-

clusion. She is heavily decorated, mainly with parrot feathers. In her left hand she

waves a Lesser Bird of Paradise plume and carries a joint of pork in her right hand

as gifts for her husband's kin. This practice of presenting a heavily decorated bride

has been adopted recently from Kuma-speaking areas of the upper Jimi.

Giewai displays Harpy Eagle feathers he hopes to exchange for money with a party

of visiting traders from the upper Jimi.

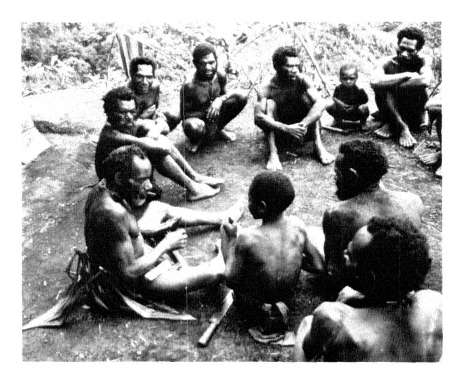

Kemba (left) displays money (folded on his thigh) to a group of fellow Kundagai.

He has been given the money by a trade partner in the Simbai Valley who asked

Kemba to get him a pig.

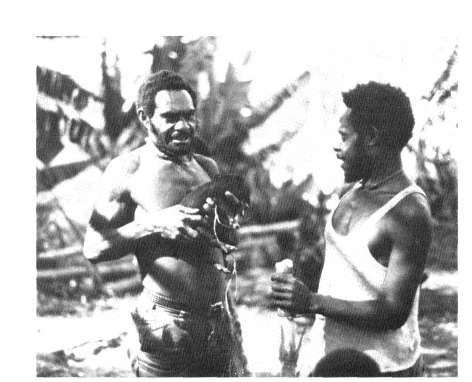

John Kandemungu (left) ponders the merits of a piglet a visiting trader from Togban

(right) wishes to exchange for money. The visitor holds a stick of sugarcane he

has been offered in hospitality.

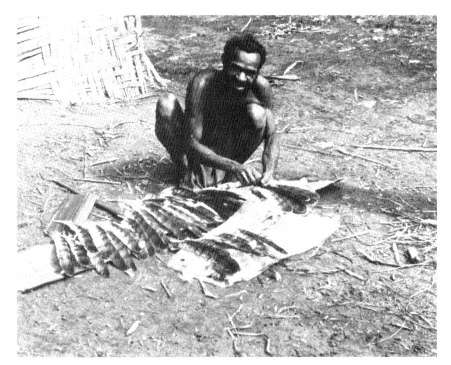

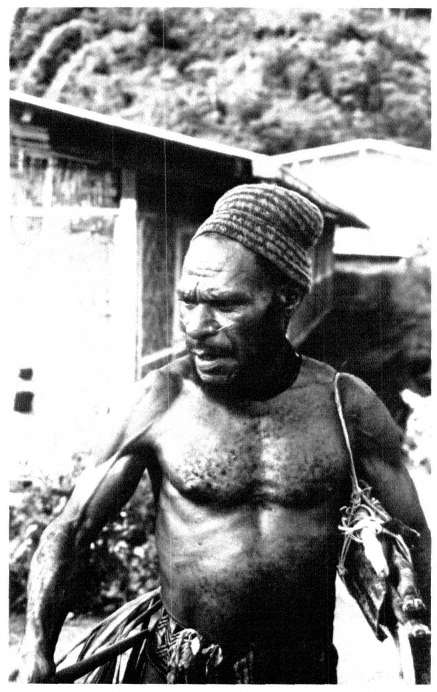

Itinerant pig trader from south of the Jimi River at festivities hosted by the Angli-

can Mission at Koinambe, Christmas 1973. Note his traditional decorations of

netted cap, slivers of bamboo in nose, and woven belt. He carries the piglet he

wishes to exchange for plumes slung in a bark roll from his shoulder. The piglet's

trotters can be seen protruding from its wrapping.

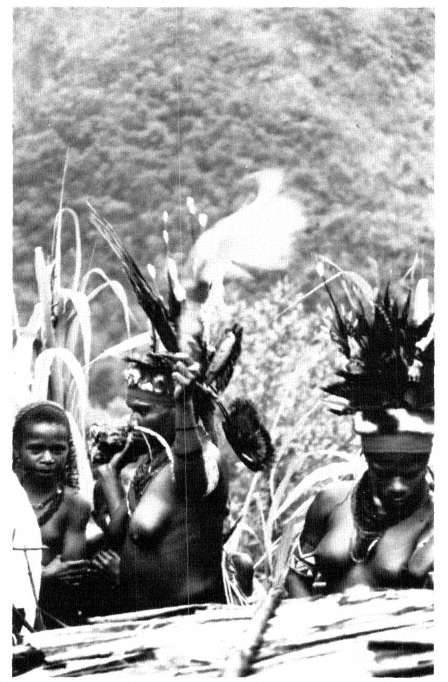

Dance contingent and spectators at a pati held in Tsuwenkai, 1974. The building

in the background is a temporary shelter for visitors. The man in the right fore-

ground has a Lesser Bird of Paradise plume in a bamboo tube he wishes to trade.

The fifteen to twenty-five age group represents young adults, the bulk of whom are bachelors attached to the households of their fathers, elder brothers, or other senior cognatic or affinal kin. The next three age groups (from twenty-five to fifty-five) represent predominantly married men with responsibilities for one or more wives, growing numbers of children, and perhaps unmarried siblings, widows of kinsmen, aging parents, and other kin. As a man approaches middle age his responsibilities for dependents tend to increase and he becomes more involved in a network of exchanges flowing from both his own marriage as well as those of other clansmen. By the time he is in his late forties or early fifties a man's conjugal family will begin to break up, with the marriage of his children. Relatively few men in their late fifties have continuing responsibilities for young children, and their exchange obligations and care of dependents have frequently been assumed by sons or younger brothers. Thus, the last two age groups represent old men, most of whose households have dissolved and who have been incorporated into the households of a younger generation of mature men.

A large proportion (all unmarried) of men under twenty-five own no shells at all. Of those that do, their stocks of kina are lower than of any other age group, although holdings of greensnail approximate the average for all age groups combined. Bridewealth forms the most important means of acquiring kina, whereas trade is the major means of obtaining greensnail shells. Most greensnail coming by trade were bought while their owners were on contract labor near Rabaul. Men of this youngest group are a significant source of new greensnail brought from beyond the locally based spheres of exchange. Kina are less often brought home in this way. It is mainly such younger men who go to work in distant areas.

Men of the twenty-five to thirty-five age group retain the largest stocks of shells. Bridewealth and trade are the most significant means of acquisition. Men in the thirty-five to forty-five age groups gain most shells in bridewealth and death payments but rely least heavily of all ages on trade for their supplies.

In the forty-five to fifty-five age group the average size of shell stocks is below the mean for all age groups combined. Receipt of bridewealth and death payments and return gifts for these are the most important means of acquiring shells. These means become more marked for the oldest two age groups.

There are two peaks of the average number of shells owned: in the fifteen to twenty-five and fifty-five to sixty-five age groups. The peak in

the younger group can be explained by their acquiring shells by trade, whereas the older group receives some by trade but most (57.4 percent) in bridewealth, mainly for their daughters. Most women are probably married when their father.,; are in this age group.[3]

If average shell stocks are calculated on the basis of all men in an age group, rather than the number of men owning shells, then the largest collections are held by the twenty-five to thirty-five age group, with stocks decreasing thereafter with age. This pattern may be accounted for as follows. Men between twenty-five and thirty-five are amassing shells for their own initial bridewealth payments. Indeed, at the time of the valuables census, several men in this group stated that they had many shells because they were about to give bridewealth. Although this group receives only 21 percent of their stocks in bridewealth, mainly for clan sisters, they are evidently receiving many shells in return for their own bridewealth payments and in return for helping kinsmen, mainly agnates, in making bridewealth payments. Of all age groups, they receive the largest proportion of their stocks in the form of return gifts associated with bridewealth.

Bridewealth increases in importance as a means of acquiring shells up to the age of sixty-five, but return gifts associated with bridewealth decrease in importance. 'This is because the major contributors to bridewealth payments tend to be younger men, whereas older men give smaller and receive larger proportions of shells by this means. Men between forty-five and fifty-five, by contrast, are the major recipients of death payments and return gifts for death payments. Such payments are mainly received for deceased married sisters and their children and for their father's sisters and father's sisters' sons and unmarried daughters. Men in the oldest age group, who are often real or classificatory fathers to men of the forty-five to fifty-five age group, are also the main recipients of death payments for the latter category of deceased males and unmarried women, who are sisters' children.

These data concern only shells currently held in personal collections. I have no comparable material on the number of shells or other valuables that men may have distributed in prestations or contributed to major exchanges of other men, and for which returns are outstanding. Indeed, this would be a fruitless exercise of computation for the ethnographer and Kundagai alike, as one can never be certain that valuables will be reciprocated in equal quantities and worth, or when, if at all. Some shells I saw in collections were already earmarked to settle existing debts. The number of shells a man may expect to exercise rela-

tively autonomous control over therefore is indeterminate and does not necessarily include all in his possession but may include some in the custody of others.

Notwithstanding these considerations, the material on existing shell stocks can be used as a basis to suggest the means of loss of shells. Although men aged twenty-five to thirty-five receive relatively few shells in bridewealth, they receive the largest proportion of all age groups in return gifts for bridewealth. Men of these ages are most active in giving bridewealth, and the large amounts they receive in return gifts reflect this. Similarly, men aged forty-five to fifty-five are not only receiving large proportions of shells in death payments but pay out substantial death payments for parents and young children. In the census of valuables, return gifts for death payments exceed receipt of death payments. As not all death payments are countered by a return gift (see below), it is probable that many of the return gifts listed are from other men whom shell owners have helped to make payments, rather than as returns for presentations their owners have made as principal donors. Men over fifty-five years old have received no shells as return gifts for death payments, and few as return gifts for bridewealth payments, which suggests that they contribute little to such prestations. This conclusion is borne out by my observations on contributions to such prestations that occurred during fieldwork.

Bridewealth becomes increasingly important with age as a means of acquiring shells, but the fact that the size of shell stocks decreases with age indicates that losses of shells, mainly in death payments in middle age and as contributions to sons' bridewealth payments which are not replaced by return gifts,[4] exceeds the acquisition of shells with advancing years. Accumulation through trade is most important for younger men and of secondary importance for men over forty-five. The latter are perhaps attempting to replenish their stocks, which are declining through prestations that are not fully reciprocated.

Regardless of age, bridewealth and associated return gifts are the most important means of acquiring shells (55.6 percent combined), with trade being next in importance. Shells received in death payments and associated return gifts are of lesser numbers, if only because death payments are smaller than bridewealth.

Nine of the fifty-five men whose shell collections I examined are big-men. Two of these (in the forty-five to fifty-five and sixty-five to seventy-five age groups) are politically influential tep yu ("Talk Men"). The other big-men are bamp kunda yu ("Fight Magic Men") and

mengr yu ("Shell Men") who are not outstanding in political affairs. The older tep yu owns more shells than the average for his age group and slightly more than the average for all shell owners irrespective of age. The younger tep yu owns fewer shells than these averages. Most remaining big-men own stocks approximating averages for their age groups. Greatest variations are two men owning no shells and one owning thirty shells. There is, then, a wide range in the collections of big-men, but there is no strong evidence to suggest that they tend to possess more shells than other men. I doubt that big-men as a category have created more outstanding debts by contributing to other men's prestations than have other men, although the younger tep yu may have done so. It is reasonable to conclude that big-man status of itself does not necessarily correlate with personal wealth.

I obtained no ordered data on the ownership of steel tools. Most men own several axes and knives, but they are often all used for everyday tasks, even if one tool is favored above others. Thus, steel tools are seldom stored in separate bundles like other valuables and, if not in immediate use, are propped up inside doorways or wedged into house walls. One man aged about thirty had a bundle of thirteen axes stored. in his house. Another man of about forty-five had five axes. While on contract labor in coastal centers most men buy several steel tools for use in their own bridewealth payments or to distribute as gifts to male and female kin. Steel tools are also bought from stores in Tabibuga, Koinambe, and Simbai Patrol Post and are usually purchased by younger men collecting bridewealth payments. Steel is also commonly traded between settlements. Most such tools, however, change hands in prestations.

I attempted to determine the size of the Kundagai pig herd on two occasions: during the population census at the beginning of fieldwork and again in late September 1974 . During the population census I simply asked men the number of pigs they owned. I did not see all animals, therefore, and, although I know at least some men gave accurate figures, some errors were inevitable by this method. The Kundagai do not appear to be secretive about the number of pigs they own, unlike, for instance, the Mae Enga (Meggitt 1974: 168, n. 8). Nor do kinsmen in other settlements agist pigs for the Kundagai to any significant extent.

A man generally divides his pigs among his wives and older unmarried daughters to care for. If his herd is larger than these dependents can care for on their own, he may assign some pigs to the care of mar-

ried sisters or his mother resident in Tsuwenkai, or to male kin who in turn assign them to their own female dependents.

In January 1974 the Kundagai pig herd was counted at 243 animals, which is no doubt an underestimate. At the end of September 1974 the number of pigs was 311. This latter count is more accurate.[5] It excludes pigs agisted outside Tsuwenkai, though probably no more than 12 animals are involved. The total includes piglets, but I do not know the age or sex structure of the pig herd. Table 17 shows the distribution of ownership of pigs by age and sex as of September ]974.

All males over about fifteen years old are potential pig owners, though few adolescents actually own beasts. Almost every male over the age of twenty-five owns at least one pig, whatever his marital status. Women do not normally own pigs over which they can expect full rights of disposal. Of the three women owning pigs, the youngest is a remarried widow whose husband lives in Bokapai with his first wife. The older woman is a vigorous and independent co-wife of a mengr yu big-man. Her two pigs were a gift from a daughter's husband. The remaining woman is a non-Kundagai widow with several young children. She lives in the homestead of her husband's brother.

All married men owned at least one pig, while one man owned as many as fourteen. On marriage a man will often be given a pig by his father or an elder brother for his wife to care for. A woman with no pigs under her charge will complain to her husband.

The size of an individual's pig herd shows an increase up to the forty-five to fifty-five age group, after which the size of herds falls. Two of the twenty-two unmarried pig owners are likely to remain permanent bachelors, as informants say no woman would consent or be expected to marry them. One, aged about thirty, is considered plim , "mad," the other aged forty to forty-five, a notorious kwimp , "witch."

Men between thirty-five and fifty-five own the largest pig herds. This may be explained by the tendency of men of these ages to support the greatest number of female dependents who can care for their pigs. Most polygynists with both wives surviving are in this age range. It is also between these ages that a man generally will have the greatest number of unmarried younger sisters or daughters to help his wife or wives and widowed mother to care for his pigs. Once a man's sisters or daughters are married they will be caring for their husband's pigs and, even if they remain within their natal settlement, the number of further pigs belonging to agnates which they can care for decreases. Thus, older men are often unable to find sufficient guardians to maintain large pig herds.

TABLE 17. | ||||||||||||

Age | A. No. | B. No. | No. | Average owned | Married | Unmarried | Widowed | |||||

potential owners | owning | pigs | per A | per B | No. owning | Av. owned | No. owning | Av. owned | No. owning | Av. owned | ||

A. MALES | ||||||||||||

15-25 | 27 | 15 | 46 | 1.7 | 3.1 | 1 | 5.0 | 14 | 2.9 | |||

25-35 | 31 | 30 | 130 | 4.2 | 4.3 | 23 | 4.6 | 7 | 3.4 | |||

35-45 | 13 | 13 | 69 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 12 | 5.7 | 1 | 1.0 | |||

45-55 | 5 | 5 | 29 | 5.8 | 5.8 | 5 | 5.8 | |||||

55-65 | 7 | 5 | 19 | 2.7 | 3.8 | 4 | 4.5 | 1 | 1.0 | |||

65-75 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 1 | 4.0 | 2 | 3.5 | |||

SUB TOTAL | 86 | 71 | 304 | 3.5 | 4.3 | 46 | 5.0 | 22 | 3.0 | 3 | 2.7 | |

B. FEMALEa | ||||||||||||

25-35 | 1 | 1 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.0 | |||||||

35-45 | 1 | 4 | 4.0 | 1 | 4.0 | |||||||

45-55 | 1 | 2 | 2.0 | 1 | 2.0 | |||||||

SUB TOTAL | 3 | 7 | 2.3 | 2 | 1.5 | 1 | 4.0 | |||||

C. TOTALSa | 74 | 311 | 4.2 | 50 | 4.6 | 22 | 3.0 | 4 | 3.0 | |||

a It is unusual for women to own pigs in their own right, and so potential number of female pig owners has not been shown. | ||||||||||||

Younger unmarried men are in a similar position. They rely upon unmarried sisters, mothers, or brothers' wives to care for their pigs. All these women may also have responsibilities for other men's pigs. There seems to be only a minor tendency for big-men to own slightly more pigs.

The average number of pigs per owner (male and female) is 4.2. This compares well with data Meggitt (1974: 168, n. 8) gives on Mae Enga pig holdings, where the average number of pigs per owner varies from about 1.9 for bachelors to 5.4 for married men, with a mean of 4.1 for all owners. (The equivalent figures for the Kundagai are 3 pigs for bachelors and 5 for married men.) Meggitt suggests his ratios are underestimates, as the Mae Enga are reluctant to reveal the number of pigs they own.

The ratio of Kundagai pigs to the total resident human population is also high by highland standards. In September 1974 there were 1.1 pigs to I person. This compares with 0.83 to I among the Tsembaga when the pig herd was at its maximum prior to their 1963 konj kaiko (Rappaport 1968: 93) (see table 19 for other Maring ratios). Ratios in the central highlands range from about 1 to 1 to 3 to 1 (Feachem 1973). It is clear, then, that the Kundagai cannot be considered poor in pigs. Although the much denser human populations of the central highlands mean that their pig populations are also much larger, it is unlikely that Kundagai husbandry practices and the work burden of women would permit a much larger pig herd. Nonetheless, informants were of the opinion that the Kundagai herds were larger prior to the last konj kaiko in 1960, although I cannot evaluate this statement. The herd is maintained at a lower level now, they say, as pigs are more frequently killed for damaging food and coffee gardens and are killed periodically to be butchered and sold for cash within Tsuwenkai. Such killings are now an important means of depleting the pig herd. Major prestations often include joints of cooked pork from one or more large pigs, while celebratory feasts and sacrifices to the spirits to cure sickness account for most other pigs. Table 18 lists the number of pigs killed during fieldwork and the principal reasons.

In addition, at least five adult or subadult pigs died of sickness or were killed by other pigs during fieldwork. An unknown number of piglets died, mostly from apparent intestinal infections. Several of the larger pigs were eaten, two being cut up for sale.

To the time of the September pig census fifty-nine pigs were killed, or nineteen percent of the then total population. If no further pigs were

TABLE 18. | ||

Principal Reason for Killing | Number | |

1. Bridewealth & other affinal prestations | 16 | |

2. Death payments | 2 | |

3. Termination of widow's mourning | 6 | |

4. Removal of food and fire taboos (in association with widowremarriage) | 1 | |

5. Sacrifice in sickness | 3 | |

6. Adultery compensations | 2 | |

7. Celebratory feasts | ||

a. return of migrant workers | 6 | |

b. for Bishop on opening of new Tsuwenkai church | 2 | |

c.for Healeys on departure from field | 3 | |

8. Garden or house raiding | 10 | |

9. Run wild | 3a | |

10. For killing other pig | 1 | |

11. For butchering and sale | 11b | |

TOTAL | 66 | |

a One agisted in Tsuwenkai for a Kinimbong man. | ||

b All or part of at least 10 pigs killed for other reasons also put on sale. | ||

acquired before November (as I suspect was the case), the loss rate of pigs by killings was 21.2 percent. The number of live pigs lost from the Tsuwenkai herd was small. Most such losses were of piglets imported by trade and then quickly exported again.

Buchbinder (1973: 131) gives figures for the number of pigs killed by several Simbai Maring populations in 1968. Comparative data are given in the following table.

These data indicate that the size of the Kundagai pig herd relative to human population is similar to ratios in other Maring settlements. The Simbai Maring are further comparable with the Kundagai in that none were collecting pigs for a konj kaiko (Buchbinder 1973: 130). A ratio of about one pig per person therefore appears to be the general size of contemporary Maring pig herds. In 1968, however, no Maring population approached the Kundagai slaughter rate. The collective kills of the Bomagai—Angoiang and Funggai—Korama clan clusters of Gunts made up the highest slaughter rate. The average proportion of pig herds killed annually for the nine Simbai populations was 9 percent.

The greater rate of killing in 1973-1974 no doubt reflects an increase in the number of pigs killed for butchering and sale. Money was still scarce in the Simbai in 1968. My presence in Tsuwenkai as a ready source of cash undoubtedly encouraged the killing of pigs for sale. If

TABLE 19. | |||||

Population | Resident human population | Pig population | Pig-per- | No. pigs killed | Percent of herd killed |

Tsuwenkai Kundagai | 273 | 311 | 1.1 | 66 | 21.2 |

Kinimbong Kundagai | 113 | 148 | 1.2 | 14 | 9.5 |

Tsembaga | 206 | 209 | 1.0 | 16 | 7.6 |

Tuguma | 253 | 232 | 0.9 | 24 | 10.3 |

Kanump-Kauwil | 342 | 354 | 1.0 | 15 | 4.2 |

Kandarnbent-Namikai | 321 | 319 | 1.0 | 14 | 4.4 |

Ipai-Makap | 220 | 197 | 0.9 | 17 | 8.6 |

Tsenggamp-Mirimbikai | 90 | 180 | 2.0 | 23 | 12.8 |

Bomagai-Angoiang & Funggai-Korama | 293 | 297 | 1.0 | 51 | 17.2 |

Kono | 121 | 113 | 0.9 | 10 | 8.8 |

MEAN | 223.2 | 236 | 1.1 | 25 | 10.6 |

a Data other than for Tsuwenkai from Buchbinder 11973). | |||||

these animals are excluded from the table, then 17.6 percent of the Tsuwenkai herd was killed. This is only slightly above the highest rate of slaughter in the Simbai in 1968. If kills for such rare events as celebratory feasts for the diocesan bishop and other visitors are also excluded, then 16.1 percent of the herd was killed. This is still a high slaughter rate.

To maintain their pig herd in the face of high slaughter the Kundagai would need to increase the recruitment rate of the herd. The major means of achieving this are by import of live pigs and a reduction of export of locally raised pigs[6] Medicines are sometimes acquired from agricultural officers at the Tabibuga government station, which help reduce pig mortality through sickness. Considerably increased import of young pigs has probably been the major factor in allowing greater rates of slaughter. I doubt, however, that pigs are often kept until they reach full size, and this may be important in permitting a sustained rapid turnover of the pig population. Indeed, a feature of the present pig herd is that it appears to be maintained at near-maximum size. Formerly, and still so among those Mating populations yet to stage konj kaiko ceremonies, pig herds went through long cycles of slow increase to maximum densities followed by massive slaughter at the end of the ritual cycle (Rappaport 1968). The present Kundagai strategy may have serious ecological consequences yet to be determined. However,

assuming that fewer pigs are allowed to reach maximum size (and certainly I saw few very large pigs), the overall live-weight of the herd at maximum numbers permitted by the capacity of women's labor to sustain them may be considerably less than that of a herd immediately prior to a konj kaiko . In short, the demographic pressure of the Kundagai and their pigs may be less than that of a comparable population approaching a kaiko .

Small numbers of live piglets are lost from the herd in trade, gifts to affines or occasionally as return gifts for bridewealth or death payments. Most pigs are nonetheless lost as pork rather than live. The same holds for the Narak and Kalam neighbors of the Maring. Unlike many parts of the central highlands where ceremonial payments may include relatively large numbers of live pigs, losses from a Maring herd do not swell the herds of recipients[7] One is led to conclude, therefore, that notwithstanding the periodic large pig kills among central highlanders, there is probably a more rapid turnover of pigs among the Mating and their neighbors. Even if Maring pig fertility is similar to that in the central highlands it is unlikely that reproduction is sufficient to maintain the Kundagai pig herd at its present size without considerable import of live pigs, mainly effected through trade,[8] a matter to which I return briefly in chapter 7.

Kundagai stocks of other livestock are low. Two men owned one cassowary each during the period of major fieldwork. One of these birds was killed as a sacrifice to the spirits during the illness of the owner's wife. Three men owned four dogs, two of which had litters. Most householders own fowls, but their numbers are few.

Prestations

So far I have identified those items traded and variables affecting the ownership of valuables. I now turn to a discussion of how these goods are distributed in prestations between groups and the geographic patterns of these movements.

Here I focus on those transactions labeled munggoi awom , "prestations," by the Kundagai. Being concerned with the establishment, maintenance, or discharge of obligations and rights, these transactions are a form of social relations grounded largely in kinship. The categories of individuals or groups making or receiving prestations are determined mainly by the patterns of past or present marriages linking

donors and recipients. To this extent, one can speak of exchange as defining groups, as Wagner (1967) argues for the Daribi (Healey 1979; LiPuma 1988).

As I have shown in chapter 1, the distribution of marriage ties has a strongly directional component and, to this extent, it follows that prestations flowing between individuals or groups related by marriage (in the same or different generations) must also be directional. If these prestations are balanced by an equal flow of similar goods in the reverse direction, then the movement of goods in prestations becomes symmetrical. In that event, prestations would effect a circulation of valuables among intermarrying communities. Where the flow of women between communities is not symmetrical, however, there will also be an unequal flow of valuables in prestations, such that prestations will serve to drain valuables from those communities receiving more wives than they themselves give in marriage.

The following payments are those that the Kundagai class as munggoi awom . In the Kundagai view the principal prestation is bridewealth, and it is invariably mentioned first in any list of payments sought from informants. This is understandable in that not only are bridewealth payments generally the largest prestations a man makes, but they should ideally continue as long as a marriage lasts. Contingent on the presentation of bridewealth and the legitimation of a union that it effects, various other prestations follow. Thus, for instance, the recipients of death payments are determined by the direction of bridewealth.

The analysis of trade in subsequent chapters is based on detailed case material of individuals' recall of trading histories. The same numerically based analysis of individuals' involvement in prestations is not possible, for informants were generally unable to remember precise details of prestations they had made. I believe this "amnesia" to be genuine, not an attempt at evasion. A few men claimed to recall quantities of valuables in major bridewealth and death payments they had made, though most could give only vague indications. It is, of course, possible that men reigned forgetfulness—especially when witnesses were present—for fear that disclosures might open them to claims on their resources by exchange partners. Yet, willing public disclosure of the composition of prestations by some men does not support such an interpretation.

There is an ideal of equivalence and balance rather than competitive

increment in Maring prestations (see also LiPuma 1988: 148, 151). Contrary to the pattern observed in certain other highland societies, Maring big-men do not gain status through the management of wealth in competitive exchange (Rappaport 1968; Lowman-Vayda 1971; Healey 1978a). Social relations stress egality rather than inequality, although this does not rule out the occurrence of imbalances over a series of prestations. This ethos of egality makes the absence of strict accounting of prestations explicable as a subversion of any certain means of evaluating individual performances against others; prestations are expected :to conform loosely to a general ideal rather than to be evaluated against specific transactions of other individuals. Thus, men can give statements about the general size and composition of different kinds of prestations in particular periods while maintaining ignorance of details of their own transactions—the number of items and the identity of those who contributed to a prestation.

Although most major prestations are made in the name of a particular individual, he receives assistance from a range of kinsmen, so that they are essentially collective transactions expressing the state of particular social relationships at specific moments in time. Despite the ideal of egality and conformity to conventional composition, there is, nonetheless, scope for a degree of negotiation on the part of donors and recipients, and for generosity in giving larger prestations than customarily expected. For example, a representative of bridewealth recipients may be present when a donor amasses valuables in his homestead prior to the ceremonial presentation. In veiled speech he may indicate the recipients' expectation of a larger prestation or try to prevent too large a bridewealth being made if he feels his group's resources will be unduly strained in providing a return gift. The possibility of generosity in major prestations introduces elements of tension into particular transactions which the collective suppression of memory prevents from developing into invidious comparisons of performance over time.

By contrast, most men show remarkable recall of the details of trading transactions. The reasons for this lie in the Maring view of trade as explicitly focusing on reciprocal and strictly equivalent transfers of objects rather than on the nature of social relationships. This is so even though trade may be an expression of, and a means of, constructing ongoing social relationships, as I argue in the final chapter. Unlike prestations, trade transactions are exclusively the private affairs of individuals, not of collectivities in public. As explicitly balanced

transactions regardless of the state of social relationships linking transactors, trade exchanges are rigorously equalitarian. Further, although particularly vigorous traders may gain some notoriety, men do not compare performances, and no status attaches to differential involvement in trade. Full recall of trading activities is thus no real or potential threat to the equalitarian social order.

Although account is not kept of the composition of prestations given and received, men do recall details of many specific items involved. Thus, in recording trade histories, I often learned of a shell or an axe that had been acquired by trade, contributed to a prestation a kinsman was amassing, and reciprocated in a return gift. The point is, however, that such accounting is keyed to specific items , not the events in which they moved in prestations. I found it as fruitless an exercise to ask men to list others who had contributed to their prestations as it was to recount the composition of prestations. For example, on one occasion I asked separately a man who had given bridewealth and his brother, who was a major contributor, to detail the composition of a prestation a few days after I had observed its ceremonial display and presentation. Their opinions differed, and neither account tallied with my record. Once assistance has been received and reciprocated the details of an event are forgotten.

In this general lack of recall of the details of major prestations the Kundagai are in marked contrast to other societies, such as the Kaulong (Goodale 1978), Wola (Sillitoe 1979), and Melpa (Strathern 1971). Significantly in such societies the social identity and status of men (and, for the Kaulong, of women also) or groups is inextricably linked to prowess in the skilled manipulation of valuables in competitive ceremonial exchange.

It is noteworthy that by the mid-1980s the situation in regard to the recall of major prestations was changing. In respect of at least bridewealth, men were beginning to claim good recall of bridewealth payments they had made, and often the composition of prestations was written down. The stated reason for this change in attitude toward recall of bridewealth was so that a donor could gain full return of the prestation in the event of divorce. Though never common after the payment of major bridewealth, divorce occasionally occurs nowadays when a young man feels that his young wife is not attending to his entrepreneurial interests. These revolve around the production of parchment coffee, as well as a man's interests in such ventures as trade stores

and alluvial gold works (see chap. 6). Concern to record exact amounts given in bridewealth does not seem to be general, however, but mostly confined to younger and more entrepreneurially ambitious men.

Bridewealth

Bridewealth payments, ambra poka ("woman price"), are often delayed until the birth of a child, by which time it is generally regarded that a marriage will endure. There seems to be a tendency nowadays for bridewealth to be given with less delay, and often before the birth of a child. Of the several bridewealth payments a man usually makes to his wife's agnates during her life only the first or second are substantial. In making the major presentation a man generally requires assistance, as he seldom owns sufficient valuables of his own. Fellow subclan members provide the most aid, with other clan members and, to a lesser extent, matrilateral kin providing smaller amounts. Bridewealth received by a man for his sister or daughter is shared out among the same kin, and such distributions are often specified as returns for aid in making the recipient's own bridewealth payment, or, if he has not yet given bridewealth, they may be counted as creating debts that can be canceled by contributions to his later bridewealth. A woman's brothers are the principal recipients of bridewealth for her, though her father may receive it if there are no true brothers of sufficient age to receive and redistribute the bridewealth.

Informants say that the amount of bridewealth given is decided by the husband. One of the bride's agnates, however, often comes to watch the husband make a final count of valuables on the day preceding the presentation. The purpose of this visit is to gauge the amount of valuables bridegivers will have to amass for the return gift, but if the bridewealth is less than expected the visitor may intimate to the husband that he must collect more valuables.

Bridewealth presentations are divided into two portions, the gi poka ("black price") of nonreturnable valuables that may be "eaten" by the recipients, and the jika poka ("return price") of valuables to be reciprocated in a return gift. This, however, must not include any items that were received in the bridewealth, so that recipients cannot rely on the prestation to finance their return gift. Even return gifts of money are made up of notes (coins are not used) that have been collected within the receiving group. The same rule applies in making return gifts for other payments. Return gifts of valuables from the bride's agnates

to the husband may be made the day after bridewealth is ceremonially presented or delayed for many months. Nowadays, a return gift of money is often made with little ceremony immediately after bridewealth is received. Return gifts of other valuables are usually delayed longer. The size of return gifts varies from about 25 percent to 75 percent of the bridewealth received. Table 20 gives details of the composition of bridewealth payments since the turn of the century.

Bridewealth for previously married women, mostly widows, occasionally divorcees, is less than for unmarried women.

Additional bridewealth payments generally consist of a single cooked pig and/or a few shells and steel tools and money. These additional payments are often made after the birth of children and are sometimes called wamba poka , "child price."

Whatever the reason for a marriage, bridewealth should be given; failure may be a cause for divorce, initiated either by the wife who feels her worth is unacknowledged and her agnates not compensated for losing her, or by the wife's agnates who prefer to reassign her to someone more likely to be conscientious in making affinal prestations.

Bridewealth received from the Kalam is usually smaller than that given by the Maring. The Kalam, however, do not expect a return gift although their Kundagai affines sometimes offer one.[9] In making bridewealth payments to Kalam the Kundagai give customary Maring amounts and receive return gifts.

It is clear from the table that there has been considerable inflation in bridewealth values, as well as changes in their composition since around the 1930s. There was a sharp increase in the number of shells, steel tools, and the amount of money passed in bridewealth in the 1960s and early 1970s, while the number of pigs increased also. Thereafter, the numbers of shells—especially kina—and steel tools included in bridewealth fell off considerably, while the number of pigs and sums of money increased yet further. Marginally more pigs were included in bridewealth in 1974-1978 than in the subsequent period, but the variation in numbers in individual transactions was lower: from two to six pigs in 1974-1978, against five to eleven in 1979-1985. It has become more common to include at least some live pigs in more recent bridewealth presentations.

Death Payments

Death payments, munggoi gwio wele awom ("valuables bones break give"), or munggoi kump-kent awom ("valuable bones give"), for

TABLE 20. | ||||||||||

Perioda | Pigs | Cassowaries | Money (K) | Axes (S=stone) | Bushknives | Kina | Greensnail | Dogwhelk/cowry ropes, headbands | Other | |

A. MAJOR BRIDEWEALTH, PREVIOUSLY UNMARRIED WOMAN | ||||||||||

1900-1910 (1) | 1 | 1 | 10S | 2 | ||||||

1930* | 1 | 12S | 1 | or | 1 | 2 | 1 tooth necklace | |||

1935-1940 (2) | 1.5 | 8.5S | 6.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | |||||

1955-1960* | 1-2 | 5-20 | 5-20 | 5-20 | 5-20 | 10-20 | ||||

1965-1970 (5) | 2 | 0.2 | 26+b | 9.6+ | 6.8+ | 19.8 | 18.2+ | |||

1973-1974 (8) | 2.6 | 0.1 | 240 | 17.5 | 12.4 | 30 | 29.8 | 0.1 | 1.3 Kingfisher skins | |

1974-1978 (8) | 8 | 937 | + | + | + | + | ||||

1979-1985 (5) | 7.4 | 0.8 | 1,720 | 4.8 | 3.4 | 7.4 | ||||

B. MAJOR BRIDEWEALTH FOR REMARRIED WIDOW/DIVORCEE | ||||||||||

1973-1974 (2) | 1 | 123 | 4.5 | 12 | 13.5 | 14 | ||||

1974-1978 (2) | 2 | 605 | + | + | + | + | ||||

1979-1985 (2) | 1.5 | 50 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 6 | 7.5 | ||||

a figure in parentheses indicates number of cases; entries in columns are mean amounts. An asterisk denotes general statement in absence of specific cases. | ||||||||||

b A + denotes additional amounts given, but precise details not remembered. | ||||||||||

males and unmarried females are given by the deceased's agnates to the group that ceded rights in the deceased's mother to that group. In most cases the transfer of rights is effected through bridewealth payments.[10] In the case of married females, the payment is made from the woman's husband to her agnates. As the Kundagai explain the direction of these prestations, death payments for all males and unmarried females are made to the deceased's ama cen , or matrikin. Specifically, the recipients are the deceased's bapa , mother's brother, and wambe , mother's brother's son. If the deceased is still a child his father makes the payment. Death payments for a married woman are given to her agnates by her husband, if he is alive, and by her sons if they are adult. Death payments are therefore clearly related to patterns of marriage.

A return gift is not always made for death payments. The practice of sister exchange and repeated intermarriage between two clans means that there will be many death payments flowing in both directions between two clans. Donors of a death payment may tell recipients not to make an immediate return gift but to count the death payment for a specified wife or member of the recipients' clan as a later return. Ideally such paired death payments should be of equal value. If this is not the case, a return gift should be made to balance the payments.

Unlike bridewealth only a single death payment is usually made. However, several smaller prestations are sometimes made to different recipients.

Informants say that death payments for people of either sex or any age are the same. Since few informants could recall exact amounts given in particular cases the statement is difficult to evaluate (see table 21). It seems, however, that death payments for young children are generally smaller than for adults and are often counted by their donors as doubling as a further bridewealth prestation.

A general inflationary trend since the mid-1960s at least, similar to that shown by bridewealth, is suggested by the small number of cases listed in table 21.

Girls' Puberty Payments

The term "girls' puberty payments" seems the most appropriate translation of the Kundagai, munggoi am yundem , "valuables breast assemble." This payment is given by a girl's father to his wife's brother, the girl's bapa , when she reaches puberty. It is generally made when the girl is between about fifteen and eighteen years of age. The donor

TABLE 21. | |||||||||

Perioda | Pigs | Money (K) | Axes | Bushknives | Kina | Greensnail | Dogwhelk/cowry ropes headbands | Other | |

1930* | 1 | 1 | or | 1 | 2 | 1 tooth necklace | |||

1955-1960 (1) | 1 | 5+ | 4 | ||||||

1965-1970 (1) | 1 | 32 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 15 | |||

1970-1974 (2) | 1 | 45 | 3.5 | 2 | 6.5 | 10.5 | |||

1974-1978 (1) | 1 | 60 | 2 | 2 | |||||

1979-1985 (2) | 3 | 394 | 4.5 | 4 | 9.5 | ||||

a Figures in parentheses indicate number of cases; entries in columns are mean amounts. An asterisk denotes general statement, no specific cases remembered. | |||||||||

receives aid from fellow subclan and to a lesser extent clan members. The Kundagai rationale for the prestation is as follows. The girl's bapa has received much bridewealth for his sister and thereby relinquishes his rights to share in bridewealth received for his sister's daughter. It is the girl's brothers or, if they are still young, her father, who are the principal recipients of her bridewealth. Yet the mother's brother has "planted" the girl in another clan,[11] and her father has benefited from her labor, and her brothers will not only receive her bridewealth but may themselves obtain a wife in sister-exchange for her. On the girl's marriage the bapa also loses rights to receive a death payment for her. The am yundem is therefore given to the bapa to compensate him for his loss of rights to share in bridewealth and death payment for the girl. At the same time the prestation discharges any further obligations the girl's father and brothers have toward her bapa in respect of her. Males retain obligations and rights of mutual aid with their bapa throughout their life.

This kind of prestation does not seem to be widely known as am yundem among the Kundagai, and it is apparently unknown in at least some other Maring groups including the Tsembaga (Roy Rappaport, pers. comm.) and the Tugumenga (Neil Maclean, pers. comm.). Many Kundagai regard such a prestation as an additional substantial bridewealth and name it accordingly. Significantly, am yundem payments approximate the value of a major bridewealth, but no return gift is received. Informants suggested that the approximate size of a prestation in the mid-1970s would be one or two pigs, K100, and twenty each of axes, bushknives, kina, and greensnail shells.

Child Reclamation Payments

Young widows often return to their natal homes or remarry into different clans if their husbands' agnates do not exercise their right to marry the woman in widow inheritance. Any children they take with them tend to become assimilated into their mother's or her new husband's clan. Occasionally a deceased man's agnates may wish to retain or reclaim his children as members of their own clan while allowing their mother to depart. This may be done by a wamba munggoi lem prestation ("child valuables give"). Such a "reclamation payment" is made to whoever assumes guardianship of the children—usually the widow's agnates or new husband. In practice the payment seems seldom given and informants could not recall any cases. They considered

that a payment of several hundred Kina and one to three pigs would be an appropriate amount.

Payment to Military Allies

On the final day of the konj kaiko festival hosts distribute salted belly-fat of pork, konj kura ("pig salt"), to those who have helped them in the last round of hostilities. Since recruitment of allies in war is an individual enterprise, these highly ceremonialized prestations pass between individuals. Allies, nokomai , are drawn exclusively from consanguineal and affinal kinsmen. They are always of different settlements, as all members of a local population participate as a single unit in warfare with major enemies.