Four

The Mind of Sugarlandia

A letter came saying that the Women's Association of Silay was composed mostly of rich families, and that, although they belonged to the elite and that they' studied in big schools in Iloilo and Manila, nevertheless, in their meetings and sessions, they used their own dialect instead of English and Spanish. This was worthy of praise. Hence, I have no doubt that this association composed of twenty girls who belonged to the rich families, will without doubt prosper.

Makinaugalingon (Feb. 8, 1916)

Though it has waned, changed, been buried Santa Iglesia is first among religions In time to come it will again arise Reappear, coming to us.

Santa Iglesia Brotherhood, "Song of the Flag"

(trans. Linda Ty-Casper)

The preceding chapter dealt with the establishment of sugar society in Negros and Pampanga during the formative years from 1836 to 1920; the present one seeks to explore some ideas, perceptions, and attitudes of participants in that society as it solidified. What events shaped the thinking of sugar people, and how did they react to the changes wrought by the coming of large-scale production? One can more readily discern the social and economic structure that sprang up in sugar country during the frontier era than penetrate the outlook of sugarmen, their mentalité , in the argot of intellectual historians. The relationship between farming practice and world outlook is a subject only recently considered by historians, and success in such studies depends on having ample statements by the participants themselves. But expressions of discontent and satisfaction, of aspirations and disappointments by the sugar people of the Philippines are not so plentiful as are data on landholding, wealth, agricultural practices, and the other circumstances of livelihood. It is, therefore, difficult to differentiate the opinions of wealthy and modest planters and of rich and poor casamac and sugar workers, if indeed there are differences. To gain even a general notion of the outlook of sugarmen, one must comb their

scarce statements and those by others who wrote about them, as well as consider their group behavior. Such an endeavor risks distortion and can lead to overly broad conclusions; however, an initial foray is worth undertaking, for during the decades of the founding of the modern sugar industry, attitudes and predilections developed that carried over into subsequence times and affected the way the industry evolved.

Hacenderos

Several important phenomena shaped the thinking and behavior of sugar planters and landowners: conquest of the frontier; acquiescence, even encouragement, on the part of the colonial government in this endeavor; strong participation of foreigners in that undertaking; and dependence on international market conditions.

Perhaps the most significant result of the transformation of the frontier into thriving sugar plantations was the considerable wealth generated, despite years of economic depression that sometimes afflicted the industry. During this era no other enterprise yielded more profit than did sugar, and the title of hacendero became synonymous with material riches. Contrary to the romanticism about heroic conquest of the wilderness that suffuses the work of writers like Robustiano Echaúz and Mariano Henson, both planters themselves, the fact persists that at its heart the taming of the frontier remained for the hacendero an economic activity, the conversion of the soil and other natural resources into investors' profits.[1]

With rare exception so-called pioneers of the industry—ex-servicemen like de Miranda and Montilla; former tradesmen and artisans like the mestizos of Iloilo and central Luzon; and erstwhile colonial civil servants, Spanish and American—moved into agriculture from other pursuits and did not actually do farmwork themselves. Advertisements of complete estates for sale on Negros appeared in nineteenth- and twentieth-century Visayan newspapers, and rentals continued to offer a door to planter status. Among later generations, a similar situation prevailed. Consider, for example, Justo Arrastia, member of a prominent Pampangan Spanish mestizo family. He finished engineering studies at the University of the Philippines, undertook graduate studies at Cornell, worked for the Bureau of Public Works, and taught at his alma mater, all before turning to farming.[2] The following note from an Iloilo newspaper conveys an impression of the way many planters approached their occupation: "A tea party will be held in 'Union Juvenal' tomorrow afternoon in honor of Mr. C. R. Fuentes and his family. They are leaving Iloilo to farm in Murcia, N.O."[3] As easily as investors moved into sugar, they just as quickly departed. At the turn of the century, Pampanga's farmers left their land fallow or turned to rice in

the face of failing sugar markets; meanwhile, under similar harsh conditions, many Negros planters simply abandoned their haciendas.[4]

One gleans a sense of how hacenderos viewed their enterprises from some observations by Francisco Liongson. A physician educated in Europe, he subsequently served as governor of Pampanga and senator from the Third District; as well, he owned extensive sugar lands. In 1911, the Philippines Free Press interviewed him on matters pertaining to sugar farming, and his remarks sparked a debate on a number of issues related to tariffs and agricultural labor. On the state of sugar farming in his province, he commented:

The sugar industry in Pampanga occupies the first place, for it is the only product exported abroad and so is the article which brings in big returns or revenues to 'the province. It is true, other products of Pampanga, such as rice, are also important, but this cereal does not go abroad but only to neighboring provinces. Pampanga produces about 700,000 piculs of sugar and when the price for a picul does not go higher than P5, the hacendero pays only his expenses, interest of 8 per cent on the capital employed, and as administrator receives for his own services only P50 a month. As a result, with sugar at P5 a picul, there is no clear profit to pay him for his trouble. And this on the supposition that everything goes well, and there are no locusts, or fires among the sugar cane, or baguios [typhoons]; and over and above all this, that none of his carabao die. But when some of these calamities come, with sugar at P5 a picul, he is headed directly for bankruptcy.[5]

Investors certainly had to learn the economics of planting and processing if they hoped to flourish, but maximization of profits remained their chief concern. Overseers and tenants took care of the everyday business of making the soil yield its fruit. Low productivity directly resulted from failure by Filipino hacenderos to pay close attention to farming methods and from their tendency to entrust supervision of their properties to employees or tenants. Some planters actively involved themselves in cane production, but many more either lacked the experience and knowledge of how to farm efficiently or showed no interest in that aspect of the business. To raise productivity required infusions of technological expertise, personal attention, and capital resources—three commodities they often sparingly offered.

Because of low labor costs and an abundance of land, however, planters earned high returns from sugar farming during the best decades of the frontier era. One of the more astute American residents in Negros, John

White, a Philippine Constabulary officer assigned there during the early American years, commented:

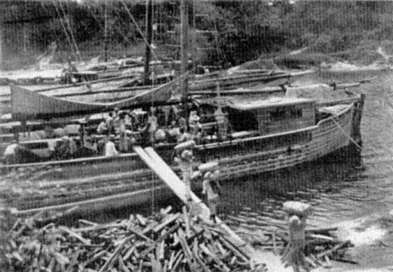

But beyond other Philippine pueblos that I have known Isabela possessed a distinctive flavor; whether it was the carelessness engendered by the proximity of constant danger or because of the large number of mestizos and Europeans on near-by haciendas I cannot say, but Isabela was always gay. The babaylanes [local insurgents] might be raiding the haciendas by day; but there would be a baile [ball] at night. Despite many years of insurrection and outlawry there was plenty of money in circulation. Let the price of sugar rise ever so little and the haciendas fairly ground out wealth from the black volcanic soil. Did the babaylanes burn the buildings? There was abundant bamboo in the foot-hills to be rafted down the river, and a camarin (storehouse) could be erected in a day or two.[6]

Rather than using their gains to raise agricultural productivity, hacenderos spent money elsewhere. The most entrepreneurial found ancillary activities in which to invest, or they turned to other financial outlets: shares of commercial banks and trading houses, money lending, trade, urban real estate, and utilities. Nevertheless, colonial policy severely limited opportunities in the broad area of manufacturing, and savings institutions did not exist before the twentieth century. Other planters utilized their profits to purchase jewelry for security against hard times or to educate their children as a way of diversifying their economic expectations. Many simply indulged in conspicuous consumption in the form of large houses, imported merchandise, gambling, religious processions, automobiles, and an extravagant lifestyle.

Sugar hacenderos became known for their liberal spending, as this quote from the Philippines Free Press suggests:

With sugar at eight pesos a picul it looks as if the halcyon days of yore were on the wing for the planters of Negros and Panay. . . .

Now it looks as if even P8.00 might not constitute the limit and that the register recording saccharine prices might not stop until it strikes an even P10. All of which means mortgages wiped off and plantations free and unencumbered and a healthy balance in the bank and large purchases and a revival of the ancient splendor and glory and royal magnificence and lavish entertainment for which Negros was formerly famed.[7]

Capampangan, too, earned a similar reputation for wealth, as evidenced by descriptions from numerous foreign travelers to the province. For

instance, José María Mourin, a Spanish visitor particularly observant of matters material, recorded at Christmas time 1876:

For our next activity we headed to San Fernando and went up to the house of the former Capitan [gobernadorcillo] named Paras, who lived with his family, among whom the one who stood out, a pleasant mestiza named Juanita.

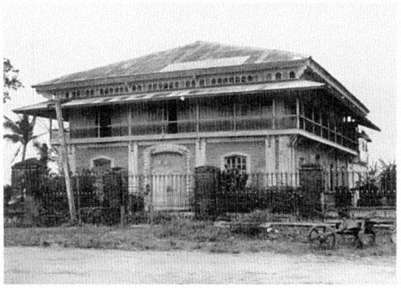

Not only did the good construction of this house surprise me, but also even the reliefs on the doors were well done, and the spaciousness of it, besides the profusion of furnishings that adorned it, and the good taste and beauty of many things, among others that caught my attention, a mirror in the Venetian style with a frame also of mirror, magnificent busts worth at least five hundred' pesos each, and a superb sideboard for silver plate in the dining room (which is a room separate from the interior gallery), that went for no less than one hundred pesos; and all that hardly benefits this rich family, since it has few needs, and only on great occasions do they light the lamps and show off the furnishings.

On a later visit to the Paras house, Mourin added:

While the others were eating. . . I could not help but focus on the contrast between the luxury, the splendor of this house, the exquisite platters, the delicious wines and all the refinements of modern civilization, with the calico shirt of Paras, his bare feet shod with light slippers, spending on this meal solely in order to entertain his guests, without having a fondness for those eating and drinking; and it's probable that a little ball of rice and viands, with their dried fish, solely constitutes the repast of Paras and his family. Undoubtedly it is worthwhile studying the indio with his mixture of plainness and ostentation, of vanity and indifference and the other multitude of contrasts that would be extensive to enumerate.[8]

Mourin's observations coincide sometimes even in small detail with those of such other tourists as Ferdinand Alençon, a French nobleman who visited Pampanga around 1850, and Edith Moses, an American who visited half a century later. Compare Mourin's remarks, too, with those of English businessman John Foreman about a hacienda in northern Negros in the early 1880s:

From Victoria[s] to Cadiz Nuevo, the route is still worse, and one has to ford several streams and a number of insecure bridges to reach the town. Instead of going directly to Cadiz Nuevo, I turned off to a place called Bayabas—to the property

of a half-cast Chinese planter, whose acquaintance I had made in Yloilo. His estate-house is the neatest and prettiest I have ever seen in any Philippine plantation. The spacious airy apartments are well furnished and decorated, whilst the exterior calls to mind a country gentleman's residence in fair Andalusia. Moreover, the furniture of the house was chosen with rare taste, whilst the vestibule and lobbies are void of that miscellaneous lumber generally found in Philippine farmery.

The owner, Don Leandro, and his Señora shewed me every attention. Ponies were at my disposal for riding round his splendid property—a basket chaise was always ready if I wished to go into town. I could bathe in the house, or I could swim in the river, the Italon diutai —with its shaded banks, two minutes walk from the house.[9]

Whether in the poblaciones of Pampanga or in the more rural settings of northern and interior Negros, foreigners encountered a form of hospitality purely indigenous in provenance. As early as 1521, a datu treated Ferdinand Magellan and his officers to a grand feast served on imported porcelain platters.[10] By the nineteenth century the ritual had changed little; only its main diplomatic purpose of putting strangers at ease had given way to a more informal function of providing visitors with respite from the journey and with evidence of a family's local standing. Furnishings and settings were more likely to be Western, reflecting intervening centuries of colonial influence.

Besides elegant meals, sugarlandia's hosts frequently treated their guests to an evening of dancing such as the ones attended by John White at the turn of the century.

The people of Negros delighted in dancing. Rarely a week passed in any pueblo but that a baptism or a birthday offered excuse to get together a few guitars or a more pretentious orchestra, clear the polished hardwood sala (hall) of some house, and tread a maze of waltzes, polkas, and rigadons (square dances) from 9 P.M. to daybreak.[11]

The first ball that White attended in Bacolod honored the visiting governorgeneral. Mourin was also invited to such affairs during his stay in Pampanga.

Other travelers to nineteenth-century Negros and Pampanga shared Mourin's view of the newly rich quality of the planter life there, of the elegant possessions out of sync with the hacenderos' own more plain, rustic lifestyle. Recent penetration by Chinese mestizos and others into the

planter group at a time when the taming of the frontier created new fortunes likely accounted for their need and ability to acquire status symbols, the fancy goods so proudly exhibited. As the period closed, however, later, better-educated generations behaved in a more sophisticated manner and became more comfortable with their use of such possessions. Edith Moses, a visitor in Apalit's most distinguished home, confirms this transition in the following comment:

The dinner was good, but dining or rather the feeding of one's guests is a serious affair in the Philippines. . . . After dinner we had music and dancing, and were delighted with the young uncle of the girls. He is a charming young man educated in Europe, yet not spoiled by his sojourn there. He was gay, unaffected, and simple in his manners. He is clever, too, and manages the large estate owned by an elder sister, who, it appeared, is a woman of character and position in Pampanga. She did not appear at the dinner and we did not see her until just as we were leaving, when a tall dark "Indian woman" appeared, who was dressed in a straight narrow skirt and a cotton jacket. She extended a hand in greeting, and our young host presented her with all due deference and courtesy as a lady who had never learned Spanish. No one seemed disturbed by her sudden appearance and there was no attempt to keep her in the background, but this dispenser of diamonds and dinners, for she owned the house and all it contained, preferred to superintend the kitchen maids and be presented to her guests later.[12]

At least one version of the contemporary social ideal of the planter class appeared in "A Remarkable Filipino Family." Written by Negrense planter/journalist Ramon Navas, the article, which was published in the Philippine Free Press , dealt mainly with the four daughters of a planter from Cadiz. Of them, he wrote:

But it is not so much that they play the piano and the violin so well, and that they shine in both Negros and Iloilo society, that the Lopez girls elicit admiration. Personally, I admire them most when they are at home.

Last week I had an opportunity of visiting their home in Faraon. While traveling for the FREE PRESS I saw many Filipino homes, but I have never been in one where so much of that right and sane Americanism, mingled with all that is best in our own native manners and customs, is to be found. As one enters the house one sees on the left a stand of books, on

the table on the other side, books again, and copies of the Ladies Home Journal, The Delineator, Woman's Home Companion, Collier's, Everybody's Smart Set, Popular Mechanics , and half a dozen other magazines, besides Manila and Iloilo and local newspapers.[13]

By the second decade of the twentieth century, this ideal of blending American culture with native refinement had spread widely among the Filipino upper class, in part because of the broad access to education provided by the colonial regime and because of closer economic ties encouraged by the Payne-Aldrich Act. In sugarlandia, moreover, familiarity with Occidental ideas and tastes became even more pronounced because of interaction with Spaniards and Americans through the industry and through intermarriage, especially with the former group.

Cultural refinement, a good education, and a reputation for lavish hospitality stood as important achievements to members of planter society, and they spent liberally to attain those goals. The image of the freewheeling, free-spending planter came to symbolize both independence of spirit and action to the hacendero class and to other Filipinos as well. Francisco Varona, a Visayan author of the 1920s and 1930s, wrote a book that revealed his admiration for the great entrepreneurs whom he described in almost heroic terms. For example, he portrayed one of them as follows:

They still recall the pomp and opulence of D. Jose Domingo Frias, the magnate who competed from La Carlota with Capitan Orong Benedicto, Sambi Hernaez and Isidro de la Rama in financial matters. Of Frias they said that, through his capitalization of haciendas and hacenderos, he could have built a larger fortune, had he been a man of greater ambition. He could have owned a number of haciendas that today would represent one of the grandest fortunes in the Philippines. But Don Jose Domingo Frias contented himself with having what, at the time, was considered the maximum in riches, with his million in properties, lorchas and cash, the product of his loans; he bridled his ambition, satisfying himself with pursuing his business at a moderate pace while he rewarded himself by living a splendid life of a nabob generously shared with his family and all his friends. He created and maintained at his own expense, and for the personal delight of his palatial house-hold, the best and largest orchestra, the orchestra Kandaguit, and in his immense dining room he maintained a perpetual banquet for guests who came regardless of the day of the week.

It is said that, once, when D. Jose Domingo Frias was playing cards, people approached him with a proposition for sale at a seductive price of a beautiful hacienda with mature cane. The potentate Don Jose Domingo did not want to listen to the proposition so as not to bother the friends who were playing with him. Well, this hacienda, having been purchased by someone else, was paid for from money produced by the sale of sugar milled from the harvested cane.[14]

In Pampanga, independence was also highly esteemed, but the more cautious Capampangan frequently tied prestige to public service and the professions as well. Being a sugar planter meant having social standing in Pampanga, and great entrepreneurs like Roberto Toledo, Jose L. de Leon, and Augusto Gonzalez were all highly admired; nevertheless, most smaller landholders needed further attainments to rise to the social pinnacle. Jose Ventura, son of a planter and nephew of Governor Honorio Ventura, acquired an advanced education in England and Spain and achieved prominence as an attorney and financier; furthermore, he married Carmen Pardo de Tavera, daughter of a member of the Philippine Commission.[15]

The ideal of the independent and achievement-oriented planter clashed with the reality of the prevalence of debt: in sugarlandia, since hacenderos frequently found themselves dependent on loans. For every Jose Domingo Frias willing to supply credit, there existed numerous farmers borrowing from him or from others. Credit and debt is a phenomenon woven into the fabric of Philippine society and is prehispanic in origin. It stands at the heart of patron-client bonds such as the tenant-landlord relationship that tied Pampangan society together and was used in various ways in other businesses in the islands. Social and political relations have long operated on a ubiquitous system of favor and obligation. In the sugar industry, however, the system of loans grew out of proportion to the availability of credit and took on more of the character of a strict business obligation.

Negrense farmers freely admitted their personal dependence on credit and its role in sustaining the sugar industry on their island. Confronted with a market crisis in 1886, a group from La Carlota and Pontevedra sent the government a petition of relief that included the following remarks:

From 1860 to 1877 was the time of the development of agriculture in the Archipelago, thanks exclusively to the special help of the foreign commercial houses that unlocked financial credits for both machinery and clarifying equipment to establish haciendas, especially for cane sugar. [The credit], if not all that was necessary, [was] at least enough to produce [sugar] under conditions of [hacenderos] being able to redeem annu-

ally, if not all their debts, at least two thirds or three quarters of them with some exception. [It was] all that some hacenderos could accomplish under the most favorable circumstances and with their best efforts.

In this whole period, due to the fertility of the soil and to the newly opened lands, even with little intelligence on the part of the majority of the farmers, the fields produced sugar in abundance so that from year to year came such enthusiasm for agriculture that peninsular and locally born Spaniards and natives who figured at least that even though they dedicated insufficient [funds] to create haciendas, by relying always from the start on the credit that they would get from the above mentioned houses, and, with the good conditions of the years cited up to 1877 and beyond, there was such abundance of production that in those years there was a feeling of well-being because the rewards more than compensated for all the anxieties of the work. The savings sugar afforded them they gradually returned to the farm as improvements that haciendas needed for completion, and in this manner at the end of each harvest and sale of sugar it always roughly came out that if they did not break even with their creditors, having very little debt they could later resort to a loan for the succeeding harvests.[16]

With the frequent downturn in market conditions from the late nineteenth century onward, the plea for low-interest credit grew into a steady refrain in sugarlandia, somewhat more strongly heard in Negros than in Pampanga. Through newspapers and reports of the provincial governors, the call for loans and mortgages came from planters and their spokesmen. Timoteo Unson, a newspaper writer and planter farming in Negros, spoke most eloquently on behalf of distressed planters in a 1913 article in the Philippines Free Press . After detailing the preceding years of disaster and pointing out that most planters did not have resources for luxurious living, he concluded:

There you have the true causes of the present crisis and it is not attributable to improvidence or mismanagement on the part of the farmers, since it has been shown how if the farmers of Negros know how to spend 100 or 200 thousand pesos on silks and jewels to please their wives and daughters, they also know how to spend eight million on work animals; if they know how to spend 100 thousand pesos on automobiles, they also know how to spend 6 million on agricultural machinery and cultivation equipment, and for such people who know how

to allocate their expenses, it is an injustice to say that they spend money on luxuries and feasts.[17]

The Iloilo newspaper Makinaugalingon (Native ways) sometimes served as the conscience of southern farmers, and, apropos agricultural loans, its editor wrote:

Many of the farmers from Negros have no clear account books. Hence, many of them were victims of a loan shark—especially if the loan money was not spent properly, but was, instead, used on things unrelated to farming, for example, gambling, diamonds, politics, automobiles, and other luxurious things. If so, the hacendero will certainly fall into the pit of bankruptcy, and, hence, his hacienda will be taken by the loan sharks. Thanks to a law introduced by Commissioner Jaime de Veyra, all luxury goods must be paid for by the owner. Perhaps this kind of law will curtail the unnecessary expenditures of some hacenderos.[18]

In reality, hacenderos and landholders employed credit in a variety of ways: to farm, to invest in newer equipment, and to retire prior debts, as well as to grant loans to their tenants and duma'an. Planters also borrowed to buy luxury goods and to invest in nonfarming enterprises. Critics and defenders of the planter way of life could find many examples of the misuse of and the need for credit, and the numerous references to this subject suggest that it remained a pressing topic in sugarlandia, particularly in the last few decades of the frontier era.

Especially in times of distress, partisans of the hacenderos spoke often and loudly of the need for survival loans: however, during good years only occasionally did anyone from the inside point to risks inherent in extravagant expenditures. In 1920, the following rather isolated news item appeared: "Representative Lope Severino of Silay recently announced that he is not happy with the luxury of the hacenderos. They should think of the future because the price of sugar might go down and the little saving they have might just disappear like a dream."[19] Here surfaces a rare testimony on a harsh reality of planter life: that big rewards from sugar farming came only intermittently. Credit remained the vehicle by which hacenderos transported themselves from one crisis to the next.

Planters in Negros and Pampanga perceived no difficulty in turning to the government for aid with their financial problems because in the past the regimes had provided them economic relief. The planter class stood as a powerful political and economic prop for the colonial administrations, and

the latter sought to assure landholders' support by following policies that would not alienate them.

To obtain such support from the government, hacenderos had learned to make use of petitions, a custom that dated back at least to 1886, when Negrenses sent Manila a nine-point proposal. By the twentieth century ad hoc agricultural associations in Pampanga and Negros, with prominent spokesmen like Liongson, Jose Escaler, Jose de Leon, Rafael Alunan, Matias Hilado, and Tito Silverio, regularly petitioned Manila on various financial matters related to their benefit. Additionally, under the United States, planters enjoyed increased say over government financial policies when sugarmen were elected first to the Philippine Assembly established in 1907 and then to the Senate after 1916.[20] The following item from the Free Press reveals how planters interacted with the government on their own behalf:

News of the possible postponement of legislative action on the project for a national bank so alarmed the farmers of Occidental Negros that a meeting of them was held in Silay last Sunday for the purpose of devising some means to avert the impending calamity. It was decided to send former assemblyman Esperidion Guanco, who was president of the first agricultural congress, and Carlos Locsin to Manila to urge upon the legislature the necessity of immediate action on the bill. According to Mr. Guanco, unless the legislature approves the national bank bill, the withdrawal of two million pesos of government money from the planters during the next harvest crop, and the shutting down of credit by the British houses on account of the war, will mean the grave of Negros agriculture.[21]

Within two years Guanco was elected to the Senate, where he ended up on the banking committee overseeing policies of the newly created PNB and supervising the activities of rural credit associations. By 1920 the leaders of the sugar industry were already influencing government policy in the Philippines; more and more sugarmen were moving to Manila to enjoy the benefits of urban life—and also to lobby for favorable legislation for their industry.[22]

As a group, hacenderos adopted a conservative stance toward the use of government in support of the common weal; rather, they supposed its purpose was to aid planters so that they could afford to help others. As noted in the last chapter, owners paid little in the way of land taxes, and the government accordingly functioned on sparse income. In 1920 the provincial government of Negros Occidental sought permìssìon from the governor-general to solicit private contributions for the construction of roads and bridges.[23] Many public expenditures in Negros and Pampanga de-

pended on private donations, a sort of noblesse oblige, and local newspapers abounded with stories of elite generosity, among them the following:

Agustin Ramos of Himamaylan, Negros, donated to the municipality a concrete school house which cost him P15,000. People rejoiced at this exemplary act.[24]

The high esteem for public instruction in this province exists, perhaps because said branch has the necessary support for its promotion and development. One may say, if no school buildings are being raised, that they begin to raise them and that they will probably raise them. Bacolor rates among others with its School of Arts and Trades; Arayat with its intermediate school; San Fernando with its high school. The erection of these buildings is through voluntary contributions of the citizens and through donations by the municipal, provincial and insular governments.

Angeles and San Luis have already collected enough money, in spite of the hard times, to build in their respective jurisdictions spacious intermediate schools. It mounts into the thousands of pesos the money gathered by voluntary contribution. Not much time will pass, if the eagerness for instruction continues as it has up to today, before all the towns in this beautiful region may count upon their own school houses.[25]

Numerous items from the local news make it clear that provincial schools, public as well as private, relied on the generosity of the wealthy, and this situation caused a writer for La lgualdad to wonder if democracy could flourish under a system where public education depended so heavily on private largesse.[26] But Negrense planters felt that they made education effective. In 1901, when the Philippine Commission met with local officials to discuss formation of a civil government, the following observation appeared:

Referring to the subject of education, [a representative from Bacolod] did not think the present system in Negros left anything to be desired. He referred to the town of Bago, where there are over four hundred children attending school. The president of that town had paid money out of his own pocket for clothing, so that the children might appear decently attired; and all this upon the initiative of the present government of Negros.[27]

Like so many conservatives, hacenderos feared that too much government would cost them money better used elsewhere. In deliberations over

creation of provincial administration for both Pampanga and Negros, questions of officials' salaries arose and were strongly debated. On the matter of taxation, the following comment appeared in the minutes:

Senor Ramon Orozco [of Bacolod], who offered to speak in English if desired, showed credentials making him the floor representative of five towns of Western Negros. . . . His towns, he said, were also pleased with the proposals as to the land tax and distributing more equitably the burdens of supporting the government. . . .

Orozco, however, went on to say that the "proletariat" class, not owning land, would pay nothing under this system, while their wages are now about eight dollars a month and on these they live very comfortably. The onus of taxation would fall on the rich, who would gradually lose their land.

Another speaker interrupted to recommend a direct tax of two dollars gold per year on the proletariat class. At present they have to pay $1.50 gold for cedulas.[28]

This last remark reveals a strong planter belief that the functions of government' did not include rectifying the income imbalance between rich and poor. Furthermore, it shows the distinct limitations on the sense of paternalism felt by the elite of Negros.

By virtue of their wealth, political position, education, and cultural orientation, the elite attained a familiarity with foreigners that made it easier for them to exert influence upon the colonial regime. Western merchants, government officials, and travelers regularly sojourned at Pampanga and Negros, where they interacted with hacenderos officially and unofficially. On Negros there existed a situation virtually unknown elsewhere in Southeast Asia, where citizens of the metropolitan country actually worked as inquilinos for native landholders. In no other area outside Manila did such an easy relationship between Europeans and the native elite spring up as in the sugar provinces. With Americans it took longer for such an interaction to develop, in part because of racial prejudices and stereotyping the new rulers brought with them and also because of the language barrier; nevertheless, when the first military officers and civilian administrators arrived in Pampanga and western Negros, they were quickly introduced to children of the elite already able to speak English, often learned in Hong Kong.[29] Official contacts between representatives of the two peoples were followed by formal social engagements that eventually led to more personal relations. To be sure, outright social equality did not exist, and Americans usually proved more standoffish than did their predecessors; nevertheless, greater dependence on native participation by

the new administration eventually eased the formality of the relationship. In no other colony in Southeast Asia did a group of natives immediately play such an influential role as did that in the Philippines. Consider that, of the original three Filipino appointees to the Philippine Commission, two—Pardo de Tavera and Luzuriaga—held sugar lands and a third—Benito Legarda—while not having sugar properties, owned other agricultural lands and a nipa palm wine distillery in Guagua, Pampanga. The general attitude of sugarlandia's elite toward foreigners appears most clearly in its response to the Philippine Revolution, against both Spain and the United States.

The Revolution, Asia's first major nationalistic movement against a Western power, stands as the most complex series of events in the archipelago’s history, and the body of literature on this subject is enormous. Historiographic disagreements about the. meaning and extent of revolutionary activity abound, and it would require at least a monograph to elucidate these debates; nevertheless, recent work on the Revolution in Pampanga and Negros has provided some insight into sugar elite behavior during those trying times.[30]

Between 1872 and 1896, members of the Filipino intelligentsia led by Jose Rizal and Marcelo del Pilar launched the nonviolent Propaganda Movement among students and intellectuals of the Christian lowlands to encourage political, economic, and religious reform of the Spanish regime. While the movement's main actions occurred abroad and in the areas in and around Manila, the turmoil reached into Pampanga when a small number of landholders such as Ceferino Joven and Mariano Alejandrino joined "subversive" Masonic lodges in San Fernando and Bacolor. A crackdown on Freemasonry in 1892 resulted in punishment of both men, the harsher sentence falling on Alejandrino, who was exiled to northern Luzon. Capampangan also shared in the student ferment in Spain, where Jose Alejandrino (son of Mariano) and Francisco Liongson joined Rizal in discussions of the colony's future under colonialism. Although large numbers of Capampangan did not participate openly in the various organizations, many undoubtedly quietly shared the sentiments in favor of reform. The province was so close to the center of agitation that the political currents of the times could scarcely have gone unnoticed or unfelt there. In Negros, however, there appears to have been little enthusiasm for the Propaganda Movement from elite residing either in the archipelago or in Europe. Negrenses studied at those same educational centers where the burning issues were discussed, but only a few converted to the cause, including Juan Araneta, a student contemporary of Rizal and Jose Alejandrino at the Ateneo de Manila and in Europe.

Open revolt against Spain broke out in the Tagalog provinces in August 1896 and culminated in victory when revolutionary troops gained control over almost all of Luzon during June 1898. The First Philippine Republic, based on the Malolos (Bulacan) Constitution, was inaugurated under the leadership of President Emilio Aguinaldo on January 23, 1899. As the fortunes of Spain declined, Capampangan and Negrense allegiance to the mother country faded as well.

Despite attempts by the Republican forces to involve Pampanga in their struggle, the province remained uncommitted during the first year. On October 15, 1897, the last Spanish governor of Pampanga, José Cánovas, wrote to his superiors:

[Since the outbreak of fighting] there was not a single moment of indecision: from the first moment until today, all the towns declared allegiance to Spain, have stayed and will stay at her side, accepting the same fate as the Spanish flag, rejoicing with the triumphs of our arms and suffering for the cause of Spain's persecution, blockade and plunder by the rebels who, on different occasions, have shown to the Pampangos who have fallen into their hands indignities for [the rebels'] having encountered in this province one of the most formidable obstacles to their intent, because Pampango loyalty has been a model of continuity for the soldiers of five provinces. . . .

A call was sounded to gather resources for Pampangos who died or were wounded in the lines of [our] army, and the province with great generosity offered her help; ask for donations for the [Spanish] patriots and at once the province will heed the call without pressure of any kind.[31]

For all its contributions, Cánovas hoped that the government would award Pampanga a permanent title such as "Muy Heroica y Siempre Fiel," or "Muy Noble y Muy Leal," or even "Muy Española."

Pampangan loyalty began to wither in late 1897 when guerrilla units of the Republican cause began to filter into the province, providing evidence that Spain could no longer control the military situation. A Capampangan from Tarlac, General Francisco Makabulos, commenced organizing clandestine revolutionary cells in every town; and the Spanish population, facing increased hostility, started one by one to evacuate the province. By the time of Dewey's victory over the Spanish fleet at the Battle of Manila Bay in May 1898, Pampanga had committed itself to the Republic, raising local troops to expel remaining Spanish forces.

The Negrenses, too, initially declared their allegiance to Spain and, more tangibly, committed men and money to the Loyal Volunteers, a locally

raised force of Spaniards and natives who joined the fighting against Aguinaldo's army from November 1896 to April 1898. The Negrenses did not support in any significant way the Republican cause, although several planters including Juan Araneta were arrested and held on suspicion.

As long as Spain appeared able to hold the upper hand in the conflict, most Negrenses stayed loyal to the mother country; however, with Spain's defeat at Manila Bay and its subsequent losses to the armies of Aguinaldo and the United States, the hacenderos began to distance themselves from their old ally. By August 1898 several towns in Negros Occidental had formed central and local revolutionary committees, and Generals Aniceto Lacson and Juan Araneta acted as regional commanders of the northern and southern sections respectively. Planters created local military units and drafted their sometimes reluctant workers to fill the ranks. Lacson even resorted to hiring Macabebe mercenaries from Pampanga to provide himself with reliable soldiers. In a move coordinated with revolutionary groups on Iloilo, Negrenses used their superior numbers to defeat small pockets of Spanish troops in Bacolod and Himamaylan between November 5 and 8, thereby ending more than three centuries of Spanish occupation.

Negrense leaders then took a unique step: instead of affiliating with the Malolos Republic, they immediately formed their own provisional government with Lacson as president and Araneta as war delegate. During the next month they created the Cantonal Government with local branches in every town of the island and opted for autonomous status vis-à-vis Malolos. This course of action did not sit well with leaders on neighboring Panay, for leaders there had hoped to include Negros in a new federal government of the Visayas they were then creating. The decision taken at Bacolod and endorsed by most planters can perhaps be seen as further evidence of a growing social and sentimental separation of Negros from its parent settlement across the Guimaras Strait.

The third and final phase of the Revolution commenced in February 1899 when the Philippine Army battled the forces of the United States, which now claimed the archipelago by virtue of the Treaty of Paris signed the preceding December. The First Filipino Republic ended in April 1901 upon the capture of Aguinaldo and his taking the oath of allegiance to the United States; nevertheless, sporadic guerrilla operations persisted in widely scattered areas including Pampanga and interior Negros for months, even years in the case of the latter. Despite continuing incidents of violence, the inauguration of civil government on July 4, 1901, signified to the elite of sugarlandia the finale of the Revolution.

Within a week of obtaining the Spanish surrender and before the signing of the Treaty of Paris, the government of Negros forwarded to the Americans a petition seeking alliance, signed by Lacson, Araneta, Melecio Severino, and other high-ranking officials. After Iloilo fell to American forces in February 1899, representatives from Negros accelerated that search. Members of both the Malolos and U.S. governments acknowledged that this defection of Negros seriously damaged the morale and prestige of the budding national government. Thereafter, in several stages, the island moved toward provincial status under the new regime, a status confirmed on May 1, 1901. These actions earned the enmity of the Aguinaldo government, and the Negrenses subsequently had to ask for help from the Americans in dealing with Republican dissidents who had secretly entered their province and harassed planters declaring their allegiance to the United States.

Leaders on Negros justified their actions in this way:

Holding the current responsibility that we have contracted before the civilized world [and] . . . considering that, having assured the internal order of this territory, we have also the duty to take precautions against the attacks of Spain or of any other foreign power, that if this event should occur, it would be the beginning of the destruction of all that exists on this fertile, rich and coveted soil, because we are prepared to repel with all our force all unjustified aggression; having deliberated with wisdom about this most essential point that demands immediate solution and making use of the authority we are demonstrating:

The provisional revolutionary government of this independent territory has agreed to take refuge as a protectorate of the Grand Republic of the United States of North America.[32]

At the turn of the century Philippine nationalism scarcely reached rural areas, and the sugar elite of Negros placed local concerns above those of a newly formed, shaky government dominated by a small group of leaders from central Luzon. From their own vantage, Negrenses could hardly have acted otherwise.

The south also faced another worry, where to sell its sugar. Exports from Iloilo had begun dropping off, and the demise of Spanish authority made existing international market arrangements unpredictable. That the possibility of renewing access to the U.S. market and of penetrating the Dingley Tariff wall occurred to leaders on Negros is obvious from the

following hint contained in a letter, dated May 27, 1899, from President Aniceto Lacson to President McKinley:

The Island of Negros, inhabited by sorts of toil engaged almost exclusively in agriculture, produces more than half of the total amount of sugar exported from the Philippines, and for this reason its inhabitants are in the majority peacable, and have gladly accepted American authority, because it is the incarnation of work and material progress, and is the generator of moral progress also.[33]

Economic interest coupled with political realism informed basic decisions made by the Negrense leadership during the Revolution.

The third phase of the Revolution proved far more devastating and divisive for the Capampangan, since a large share of the fighting happened on their turf, leaving their land ravished and many of the poor famished. No neat political swings occurred, and questions of loyalty became confused because of shifting military control, physical and psychological coercion, and the raging guerrilla warfare that engulfed the province. Broadly speaking, Capampangan began this phase overwhelmingly in support of the Republic, but by the time the period ended, with the creation of Pampanga Province under the American civil government in February 1901, a majority of the elite backed the new colonial regime. Many local civilian leaders participated in the Malolos government, and Maximino Hizon and Jose Alejandrino as well as Servillano Aquino and Francisco Makabulos from Tarlac served loyally in the top ranks of the army. Residents in the province 'provided soldiers, logistics, and moral support to the cause, even as U.S. forces began to invade its borders.

For roughly the next two years, the provincial elite found themselves trapped between two contending parties, each demanding their allegiance. Guerrilla intimidation of planters to hold their loyalty was matched by U.S. coercive pressures to end their support for the Republic. Murders, kidnappings, burnings, arid robberies marred tranquility until the Americans finally mastered sufficient control of the countryside. As peace returned, more and more hacenderos—including such former loyalists as Liongson, Joven, and Enrique Macapinlac—committed themselves to the new order. Others, such as Hizon, Alejandrino, and Pedro Abad Santos, even after their capture remained true to the cause.

The majority of the elite in Pampanga seemed to swim with the tide of whichever side controlled the province, but such an observation obscures a more complex reality. The elite espoused a conservative ideology that called for order and the sanctity of private property, and they gave their

allegiance to the government—Spanish, Philippine Republican, or American—that appeared to provide them the best guarantee of stability. At times when it was not clear which faction would win, many Capampangan paid a heavy price for making a choice, suffering death, injury, and/or loss of property. When the Americans emerged at last as the victors and supported the traditional order, the elite backed them, even at considerable risk to themselves. While their revolutionary experience differed, the sugarmen of Negros and Pampanga shared, finally, a common desire for tranquility, peaceful commerce, and the preservation of their own estates, aspirations the Americans promised to respect. To those ends, national independence took a back seat.

Planters of sugarlandia subsequently subordinated their desire for political freedom to their need for markets. No more striking evidence of this attitude can be found than in debates over passage of the Payne-Aldrich Act in 1909. This tariff bill offered duty-free access to the U.S. market for large quantities of Philippine agricultural commodities, including sugar, in exchange for free entry to the archipelago of American manufactures. Filipino nationalists opposed this bill, correctly anticipating that it would create an economic reliance on the United States that would delay political independence.[34]

Sugarmen did not begin their quest for American tariff preferences with the idea of compromising Philippine independence, and not all hacenderos favored the 1909 arrangement; however, in the end, the majority of them chose economic advantage over other considerations. In September 1901, scarcely had civil government come to the provinces when planters in Negros and Panay petitioned Governor-general Taft for reduction of duties under the Dingley Tariff, and this plea continued for the next eight years with planters from the south even taking their case directly to the halls of the U.S. Congress.[35] Spokesmen for the Negrense planters did not view tariff relief as a brake to the drive toward liberation but rather as part of a package of relief for their depressed industry. In his report for 1906, for example, Governor Melecio Severino, after outlining the economic hardships confronting Negros, wrote the following:

Such being the calamities afflicting agriculture, with which the planters must necessarily and desperately contend, it cannot be hoped to bring about an improvement of agricultural conditions by their unaided efforts or without the decided protection of the Government.

It therefore becomes necessary for the Insular Government to exert itself on behalf of the Islands for the enactment of legislation which shall free from customs duties agricultural

machinery and implements; which shall encourage the establishment of agricultural and mortgage banks, and which shall reduce or abolish the Dingley tariff on sugar. It would also be advisable for the Philippine Commission to appropriate Insular money for the extermination of locusts and grasshoppers and to enact a law regulating plantation labor.[36]

Capampangan, in contrast, because of their proximity to the capital and its politics and because of their closer ties to the old revolutionary cause, showed greater understanding of the dangers inherent in tariff concessions. In 1905, a group called "Comite de Intereses Filipinos," made up of more than a hundred of the province's most influential agriculturalists and professionals, sent a long petition to Secretary of War Taft, listing thirty desired changes. Unlike the usual solicitation from Negros, the document encompassed all the points of the current nationalist agenda, including demands for a specific date for independence, formation of a legislative assembly, trial by jury, revision of the sedition and libel laws, reform of the constabulary, change in the composition of the Philippine Commission, reduction in the alcohol and land taxes, and equal pay for Filipino and American officials. All these changes and others preceded pleas for tariff consideration for local commodities. Indeed, the petition raised so many politically sensitive issues that the senior inspector of constabulary for Pampanga secretly investigated the origins of the document and reported on its organizers to his superiors.[37]

Because of differing political traditions and perhaps because Pampanga possessed a more mixed economy than did Negros, Capampangan remained more divided on Payne-Aldrich than did Negrenses. At the time of the passage of the bill, debate in Pampanga, pro and con, raged "redhot," in the language of the Philippines Free Press .[38] Nevertheless, confronted with the reality of their dire economic conditions, hacenderos supported the compromise. As Governor Arnedo, himself a sugarman, wrote in his annual report:

As to the general opinion regarding the results expected from the Payne Bill after enactment thereof by the Congress of the United States, so far as the agriculture of the province is concerned, this bill was in general well received by the majority of the inhabitants of the province, and although a small minority appeared to sustain the contrary opinion, in the sense that the effects of this bill, instead of being beneficial, will be detrimental to the interests of the country in general and the province

in particular, it may be affirmed that this was but a play of party politics.[39]

In Negros the reception of "Bill Payne" was even more enthusiastic, although even in the south some reservations about its political implications surfaced. Governor Severino wrote in 1909:

By the foregoing brief statements of the prices that prevailed in the Iloilo market, it will be seen that sugar quoted highest when favorable news of the bill was received.

The rise in prices naturally caused the planters of Occidental Negros to form a favorable opinion of he Payne bill, although this opinion was divided with respect to the considerations relative to its transcendental influence on the political future of the Islands.

The majority of the planters, realizing the palpable results which will accrue to agriculture in the future from the enactment of the Payne bill, as it will create a market for Philippine sugar, paid no attention to the efforts made to make a failure of every public meeting held in its favor, and in important assemblies convoked by the municipal presidents of different places, not only said that they favored the bill and asked for prompt enactment, but also would accept free trade, provided that Philippine sugar was admitted duty free into the United States.[40]

After enactment of Payne-Aldrich, sugar farmers of both provinces, although they gave occasional lip service to the idea of independence, cast aside any reservations once favorable market conditions appeared and came to rely almost entirely on sales to the United States. In 1915 the Agricultural Association of Pampanga, representing the most influential of the province’s agriculturalists, wrote to Resident Commissioner Manuel L. Quezon in Washington, asking his help to continue the existing tariff preferences, for without them the Philippines could not compete with Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and U.S. domestic producers for a piece of the American sugar market.[41]

The following year the U.S. Senate added to the pending Jones Bill the Clarke Amendment that promised independence for the Philippines within two to four years. While this amendment ultimately met defeat, it evoked the following response from Jose Ledesma Jalandoni, a Negrense planter whose opinion represented that of a strong segment of sugarlandia:

I am not opposed to independence, but I believe that ample time for preparation should be allowed us so that we can devote all our efforts and energies to the development of the vast

agricultural resources of our country. 'Let us urge the establishment of agricultural banks, sugar centrals, railroads and all that is necessary to develop our national resources, for, with the individuals prosperous as they should be, .the government which derives from them shall be able to establish coast fortifications, a respectable navy, a well organized army and acquire sufficient war implements and ammunitions to enable it to meet other nations shoulder to shoulder, or breast to breast. . . .

The great majority of our professional and ignorant politicians are actually insisting upon independence under whatever form without calmly considering the responsibilities that it brings with it. They have flattered and seduced the people into this belief, call us "traitors" without stopping to ascertain that the interests of our country are dearer to our hearts than to theirs. Let us not be deluded by the emotion of beholding our dear flag unfurled on the shaky mast which may break never to rise again.[42]

Demand for a stable market, like the need for a steady source of credit, imposed sharp limits upon the economic and political choices of these otherwise powerful and independent-acting planters.

Casamac and Duma'an

Before World War II, the Filipino poor left little printed testimony concerning their reactions to events that changed their lives. Moreover, many of those in the past who claimed to speak for tenant farmers and laborers exhibited little understanding of or empathy with them. Often these putative spokesmen represented the interests of the upper class rather than those of their adopted charges. Historians recently have pointed out that, in several instances at least, the rural farmer's world view differed widely from that of the landholder, that the two outlooks were positioned at a greater distance from one another than is normally implied in the great tradition-little tradition dichotomy. Patron-client paternalism did not necessarily produce the kind of symbiosis that allowed planters to fathom the thinking of those who labored in their fields; rather, opportunism, a patronizing attitude, and even adversariness characterized that relationship. Evidence suggests that workers in sugarlandia shared this same fate of being little or badly understood by litterateurs.[43]

In 1964, as part of my research on local history, I conducted an anonymous informational survey among older men in Pampanga concerning their memory of their lives before 1920. Among the respondents, 149 former sugar tenants and thirty landowners provided data about their

residence, education, and employment in the sugar industry during this century's first two decades. Aside from brief, biographical answers, many of these interviewees, who ranged in age from 69 to 104 years, volunteered more extensive comments about their work experience. Their insights, given to the local teachers and college students who acted as surveyors, offer some unusually frank comments on tenant-landlord relations. The forty-four intervening years, eventful and tumultuous as they were, did not erase for some of these old men vivid memories of their days laboring in the sugar industry.[44]

Perhaps the clearest notion that emerged from these interviews was the contrast in perceptions between landlords and casamac about their relationship: landholders considered that their tenants felt a deep sense of gratitude toward them for the treatment they received, while tenants often expressed resentment and fear. The following statements demonstrate this contrast, the first from a landholder in Angeles:

My brother and I tilled the soil—our own land—and had helpers, wards of my father. We treated them like members of our own family. They lived with us. We supplied their necessities and we did not maltreat them. I remember they loved us very much. My father saved one of them from the Guardia Civil during Spanish times. My father held the position of cabeza.[45]

A retired school teacher and hacendero from Guagua described the samacan system in these terms:

We were like one big family. They treated us like their parents and we treated them like children. When the planting began and they came to the house for the cuttings, they brought along firewood of their own volition, and I was thankful for their gesture of kindness.[46]

Another planter, from San Fernando, added:

My father was a farmer with around a three-hundred-hectare hacienda. . . . The sharing of crops was fifty-fifty and the expenses were also on a fifty-fifty basis. The tenants loved my father. They would come and help us during fiestas, bringing us gifts of fruits, chickens, and sweets.[47]

While some tenants considered their landlords paternalistic, the majority were more resentful. An 84-year-old tenant from Porac gave the most positive comment about the relationship:

The tenant and the landowner share fifty-fifty. . . . The landowner calls for the tenant when the Chinese buyer comes—

everything is done in their presence and with their consent. No interest on money and rice. The landowner (Hipolito Coronel) was very humane. He treats his tenants as member of the family. The tenants are served their meals at the family table.[48]

On the other side, a casamac from Guagua stated:

The tenants would serve the landlord by cutting wood for fuel for him, cleaning his yard and his house, and giving him gifts of chickens, firewood, and carabao milk whenever he had a fiesta. No request of the landlord was ever turned down. Of course, the landlord had a way of discriminating among his tenants. It must be kept in mind that the landowner has foremost in his mind the increase of his production. Nevertheless, there were times when a landlord would remove his tenant from his farm for failing to please hirn. There were even cases when the landlord cut out the ration of the tenant altogether.

A common practice of the landlords at that time . . . was that every weekend when the tenant's wife went to see the landlord for the next week's ration, she was made to clean the yard, the house, or made to cook the landlord's meal before she was given the ration, which time was usually shortly before noon or even later.[49]

Another, from Angeles, said:

My landlord would ask me to do odd jobs for him without pay, even to the extent of cutting wood, which was about three carloads, and delivering it to his house. My wife used to dean clothes and clean the house of my landlord. She, too, received no compensation for it. At the end of the milling season our debts were cleared. Of course we were the poor, then oppressed by the rich. I did not complain. We were not allowed to, and nobody dared to.[50]

Fear of landlords appeared in numerous comments, including one by a tenant, 73, from San Fernando:

I started selling firewood at the age of about ten or eleven years old. We were very poor. My father was a tenant farmer. He had no carabao. . . . At that time we were much afraid of our landlord. My father could not answer back for fear of be-

ing removed from his work. My father's landlord cheated my father.[51]

One from Mexico testified:

My landowner was the kindest among the Panlilios. I was formerly a tenant of Don Vicente Panlilio, but something happened. I asked him once if he thinks that the price he gave to my crop was too low. But it happened that he was out of mood at the time I asked him. I have always considered myself one of the most faithful tenants, but that time he got angry with me and he started shouting at me. Plenty of co-tenants heard me because we were in the fields at the time. They were angry at me because I didn't assert my right. They said I was a weakling. All of them were mad at Don Vicente. Then it happened that Don Bengang Panlilio, his cousin, needed one more tenant, and I asked Don Vicente if I could transfer to his cousin's hacienda. He was no longer angry at that time and he refused to let me go. My landlord was just temperamental. I understood his moods because I knew he has some Spanish blood.

Later on Don Bengang asked Don Vicente if he could spare one, and that was when I transferred to Don Bengang's hacienda. He was a very kind old man—very fatherly; although he also had some bad moods, he was very kind compared to Don Vicente. There were even some brothers of Don Vicente who whipped their tenants.[52]

That whippings occurred on occasion was confirmed by another Mexico tenant, age 78, who revealed:

During those times even grown men got beaten when the landlord, Pablo Panlilio, did not like what he did. We said a tenant was given "two cavans" if he gets whipped fifty times, because one cavan was equal to twenty-five gantas. . . . And the whip he used was not just an ordinary kind, it was especially made for the purpose of whipping tenants. It had a leather case, the handle was made of a metal and gold plated, and the stem was of thick rounded leather. When the landlord asked his servant to bring out the whip, everyone in the barrio trembled in fear. Even how much one hated the tenant being beaten, one felt pity when the whip was taken out. Everyone gathered to see, and the family most of the time cried for mercy. The landlord rarely used the whip, however. He used it only in extreme cases, but I did see him use it once when I

was a small boy, and the memory stayed long in my mind. The tenant was not like a human being when he was being beaten. During the first few whippings he shouted in pain, but after that he did not cry anymore, because he became numb.[53]

If Pampangan tenants expressed a sense of helplessness in the face of planter power and authority, they also conveyed a sense of hopelessness as well. A 76-year-old tenant from San Fernando offered a common sentiment of the era:

Although the sharing of crops was on a fifty-fifty basis, the tenant shouldered his expenses on the farm. Whatever he got from his landlord in cash or kind (cigarettes, rice, sugar) he paid back. He worked for his landlord like a slave. . . . What was not quite nice was that most landlords cheated their tenants. . . .

The tenant does not get his share of the harvest because he has no place to store it' and he does not have connections with big buyers like the Chinese, et cetera.[54]

The endlessness of unrewarding work appeared further in a statement from a 100-year-old tenant from Angeles:

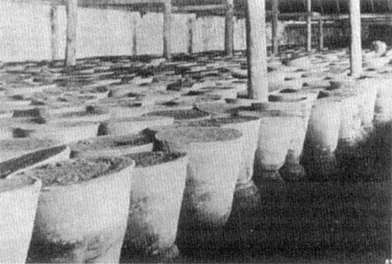

I was supposed to receive one fourth of the sugar production which we placed in pilones. No sugar and no money was given to me in return, for my share was kept in my landlord's storehouse. He sold my share as he pleased without my knowing the selling price. I was just informed of the cost of my ration every time I came to get it. At the end of the next harvest, I was informed of the balance of debts. I got so fed up with such treatment that I gave up the work. My son who was then quite big worked in my stead.[55]

Landholders at their most paternalistic expressed their reluctance to loan money, for it encouraged long-term indebtedness, and three of them commented:

I used to limit the loans of my tenants, because I wanted them to make a little sacrifice for their future. I did not collect interest on money I loaned them. I even gave them lessons on how to produce more, once in a while.[56]

When I lent my tenants any amount of money, I charged twenty percent interest to prevent them from borrowing often and spending the money for gambling. When my father died, I canceled all debts of my tenants.[57]

My father . . . always gave his tenants money as often as they came to borrow, so that when I took over, I found many of the tenants with debts as big as five hundred pesos, six hundred pesos, and a thousand pesos. There seemed to be no way by which they could pay their debts, so I forgave them their debts and told them to start anew. I often gave them lectures on thrift. There were two bad traits I observed common to most tenants—indolence and extravagance.[58]

Despite these charitable sentiments most tenants borrowed to survive, and most landholders loaned them the cash, the majority of the latter charging some interest rate between 5 percent and 20 percent for cash. And this system resulted in a recurring round of indebtedness that left tenants without hope of breaking free. A 95-year-old tenant from San Fernando revealed his thoughts in this manner:

The landlord at that time would give you any number of pilones of sugar as he pleased. We could not complain for fear of being removed from our work. We were much cheated and we poor people were treated as servants. We worked as tenants to pay for the debts incurred by our parents, and our children would in turn work as tenants to pay for our debts to our landlords. We worked day and night. The landlord's word was law.[59]

Perennial debt and inability to alter their situation informed the thinking of casamac in Pampanga; however, these attitudes did not necessarily determine their reaction to a specific hacendero. Rather, along with adequate subsistence tenants expected, even insisted upon, fairness from landlords. Casamac opinion about their relations with others as well depended on this need for fairness, and wrong was measured by just how inequitably someone treated them. The following narrative concerning the arrival in 1916 of the cadastral survey in Magalang reveals a long-remembered slight harbored by a 74-year-old tenant of that town:

I remember clearly—the police came and gathered us. They told us to go to the tribunal [municipal building]. But we were afraid of the police then, and we never wanted to go near the tribunal for we associated it with being imprisoned. They told us to register our land, but we didn't want to have anything to do with the police. We didn't go to the municipal building, and they came and asked us why. We told them we were very busy working in our fields. They then told us that a man would register our land for us. We were ignorant at the time

and we were happy that this man would register for us. We found out later he registered it in his name.[60]

Most tenants in this era possessed no legal claim to land, only traditional rights through the samacan, and the registering of titles did not directly affect them; however, the perception of inequity on the part of those associated with the survey made many tenants view the cadastral program negatively.

Casamac operated on a basic sense of justice in dealing with landholders; and above all the implied paternalism, they needed to be satisfied that they received enough and that their contracts operated fairly. A tenant from San Fernando expressed this sentiment succinctly:

During that time the landlord bore all the expenses on the farm, and all the production went to the storehouse of the landlord. He gave us our necessities—food, clothes, shoes, and other things—and we did not know our share. We just lived buried in debt to our landlord. We were like members of his family. He disciplined us and we were afraid of him. We were not given enough subsistence and we left him.[61]

The samacan functioned in such a way that tenants seldom improved their economic condition, largely because opportunities to profit all remained in the hands of hacenderos. The latter kept the books, warehoused and sold the finished product, set interest rates, and often loaned stores, equipment, and draft animals. Choosing where to profit at the expense of tenants remained a matter of individual landlord style, and the manner selected often determined casamac reaction. Charging moderate interest on loans did not appear to cause undo reaction, providing other parts of the contract proved acceptable; charging no interest compensated for other exactions by the hacendero. A satisfied tenant from Guagua described his relationship this way:

My share of the sugar was paid in cash to me by my landlord, usually a peso less than the current selling price. The molasses went to my landlord. Any amount of money I borrowed from my landlord did not bear any interest. The relationship between us was paternal.[62]

By far the biggest perceived inequity on the part of tenants dealt with the matter of selling finished sugar to brokers. Planters often did not seem to realize the distrust they created with these financial dealings; rather, they believed that they did the casamac a favor (or fooled tenants into

thinking so) in handling the complex negotiations. Three landlords gave different justifications for dealing alone with the Chinese brokers:

During those times tenants were treated very well by us. We did not ask any interest. . . . They were free to ask for help anytime they needed it. Only we were the ones who purchased the whole crop, including theirs, because they might be cheated by Chinese merchants.[63]

When we sell the sugar I got the average price of sugar and I multiplied it by the number of piculs. That was how I gave an accounting to the tenants. Sometimes I sell several piculs at a certain price and the week after I sell several other piculs at a higher price. I get the average of all these prices and that was the price I based the accounting on.[64]

If I sold a pilon of sugar at twenty-five pesos, I charged it to [the tenant] at twenty-four pesos. My gain was one peso, which was in the form of a gift to me for selling my tenant's share.[65]

No matter how hacenderos justified their negotiations, tenants found them the greatest source of injustice in the samacan contract. Two representative tenant comments reveal the hostility and misperception that underlay the Pampangan labor arrangement:

In sugar production we farmers were cheated most of the time. If a pilon of sugar cost twenty-five pesos in the market, the landowner will first tell the poor farmer any amount he wishes to tell him. Any complaint by the farmer in this accounting will mean his firing from his job.[66]

The landlord treated us kindly in words. I know very well that they were cheating me, especially in sharing the crop, which is supposed to be on a fifty-fifty basis. . . . And when it comes to sharing harvested sugar, the crop was first put in the bodega of the landlords. Then they did everything they can to cheat us. However, they lend us money without interest, provided it will be paid back in not longer than one year.[67]

Tenants who sold their own share usually defended their samacan relationship as fair, but such individuals remained a small minority. Perceived inequities as early as the first two decades of the twentieth century threatened the social order that had developed over the preceding years.

In 1970 a similar survey collected responses from duma'an and other sugar people from Negros concerning their life in the two decades before

World War II.[68] Among the interviewees were eighty-two duma'an from 70 to over 100 years of age who supplied observations concerning their early days working on haciendas. Because of the time lapse between the two surveys and the different period emphasis of the later one, the data collected are not quite comparable; nevertheless, these older Negrenses did offer recollections of the late frontier period. And their comments on their working life contrasted in some ways with those of Pampangan casamac.

Duma'an evinced somewhat more satisfaction with their conditions than did their northern counterparts, perhaps reflecting the better market conditions that prevailed in Negros in the the early twentieth century. While no hacienda laborer admitted to improving his circumstances, they generally felt their subsistence needs were met. An 80-year-old retiree from Murcia supplied this response:

My life as a hired worker of the hacienda was much better during that normal time, even though wages were so small as compared to wages now. At the rate of fifty centavos a day I could still support my family, since prices of foods were very much lower as compared to prices now. I can also let my children go to school, but, due to their [negative attitude], they didn't even reach the intermediate grade.[69]

Several of the comments, however, contain a certain ambivalence: their wages had to suffice, because no alternative sources of livelihood existed. Three examples from octogenarians in. Hinigaran, Isabela, and Himamaylan exemplify this sentiment:

We received no consumo [rations]. . . . Life was hard but I couldn't complain about my financial problems for fear of losing my job. I had to work in the field every day, even when I wasn't feeling well, since my earnings were paid on a daily basis.[70]

We were given consumo and the amount was deducted from our salary. I was contented with my earnings. It was a hand-to-mouth way of life. I supported my family with my meager income. Everything was cheap during that time, so no worry at all, although this income was not enough to meet daily needs.[71]

There were no major troubles, although the landowner didn't give any privileges to his laborers. They couldn't get any cash

loans from him, nor get any help in bad times. Laborers would just have to bear the kind of management they have.[72]

The remarks of the minority who proclaimed dissatisfaction with their hacienda wages contained overtones of a fear and helplessness that bonded them to their poor situations. Three retired duma'an, two from Pulupandan and one from Binalbagan, made representative comments in this vein:

There were no labor troubles. If you do good in your work you won't have any trouble at all. They were treated well by the owner, if they only follow what the owner would like them to do.[73]

Laborers couldn't complain—otherwise they'd be ousted. They just waited for instructions and payday. They never complained because they reasoned that the landlord wouldn't help them anyway.[74]

I just obeyed orders. At times I complained to the cabo because of too much work, but the cabo didn't listen to my complaints. I just worked and obeyed orders.[75]