The 4th-Century Temple of Zeus

The 4th-century Temple (Figs. 44 and 45) used three architectural orders: an exterior Doric peristyle and an interior Corinthian colonnade which was topped by a second story of the Ionic order. It had a pronaos in antis , or porch with facade columns framed by antae , and, in keeping with a tendency of 4th-century building, omitted the opisthodomos , or rear

Fig. 45.

Restored eastern facade of the Temple of Zeus, from Hill, The

Temple of Zeus at Nemea , Pl. VI.

porch. At the rear of the cella, in place of the opisthodomos , was an adyton (the innermost room of a temple which was "not to be entered": we might say "the holy of holies").[73] Another characteristic of its age is the shortened plan with six columns across the facade and twelve along the sides as opposed to the Classical proportion of six by thirteen. The crypt within the adyton is an unusual feature. The finished building contained no sculpted decoration. Although conservative in design, the Temple shows great care and precision in execution and, in several instances, interesting solutions to structural problems.

Building Materials . Most of the stone used in the 4th-century Temple is limestone, certainly quarried from the low

[73] For omission of the opisthodomos in the 4th century, see G. Roux, L'architecture de l'Argolide aux IVe et IIIe siècles avant J.-C . (= BEFAR 199, Paris 1961) 328; for the adyton at Bassae, ibid . 58-55; for the adyton at Delphi, G. Roux, Delphes: Son oracle et ses dieux (Paris 1976) 101-17.

ridge running along the eastern side of the valley between Nemea and Kleonai (see p. 10). Although the stone has become hard and gray from exposure and weathering, when first cut it is actually soft and sandy reddish limestone. Blocks of the same limestone from the Early Temple were reused along with newly quarried stone in the foundations of the 4th-century Temple. Newly quarried blocks were used in the superstructure. Black marble was used for the threshold of the cella door.[74] Soft limestone was used in the interior for the Corinthian capitals of the lower order and for the Ionic upper order. This stone is easier to carve, and within the cella it would not have suffered from exposure to the elements. The limestone was coated with a fine white stucco, which served both to protect exposed surfaces and to decorate the stone. Traces of blue and red decoration appear as well.[75] White Pen-relic marble was used for the sima (a typical feature in 4th-century architecture of the Argolid).[76] The roof was constructed of wooden rafters over which terracotta roof tiles of local manufacture were layered.

Foundations and Krepidoma . The krepidoma and its foundations (Fig. 46) may best be viewed at the northwest. The foundation blocks of the peristyle continue for seven courses (2.80 m.) below the euthynteria . A series of parallel foundation walls, three or four courses deep, supports the interior paving. The north-south orientation of these walls in the cella is visible where the paving is broken away; in the pro-

[74] Some of the threshold blocks were removed from their original position sometime between 1915 and 1924 (see Clemmensen and Vallois, op. cit . [n. 13] 1-20, Pls. I-II and Fig. 5, where the southern portion of the threshold was apparently still in situ ). The stone is similar to that employed in the Tholos at Epidauros, which is referred to as "black Argive stone" in the building accounts there (IG IV 103.15).

[75] These traces occur on triglyphs (blue) and metopes (red); on one of the cornice blocks, where the mutules are blue and the fascia red; and on the plastered surface of the underside cyma reversa molding, where fine incised lines indicate that it carried a painted Lesbian leaf decoration.

[76] Roux, L'architecture, op. cit . (n. 75) 328.

Fig. 46.

Restored longitudinal section of the Temple,

from Hill, The Temple of Zeus at Nemea , Pl. VIII.

naos and the crypt the walls run east-west. The space between them was originally packed with earth and construction debris such as stone chips.

Building Techniques . The Temple measures 20.09 by 42.55 m. at the stylobate level. Squared blocks laid next to and on top of one another in typical Greek fashion are held together, if at all, by iron damps and dowels. These iron clamps, of a hook type with lengths ranging from 0.30 to 0.40 m., were sealed into their cuttings with molten lead, which prevented air and moisture from rusting the iron and which acted also as a cushion to absorb shock and to provide a certain flexibility. Few examples of either clamps or dowels remain because the demand for iron and lead during the Early Christian and later periods claimed most of them. Two damps, however, may be seen at the center of the western end of the Temple, and a fragment of an iron dowel with some of its lead is in the museum (IL 236; see case 20, p. 67).

Although the vertical joining surfaces of blocks were treated with anathyrosis , hard and soft pockets in the limestone made the working of perfectly smooth surfaces difficult. To obtain the tightest fit possible, a saw was run through the joining surfaces between blocks so that they would mirror each other. Traces of saw marks are visible on several blocks.

Fig. 47.

An empolion.

Column drums were aligned by means of empolia , the square cuttings for which are visible in many fallen drums around the site. A pair of wooden blocks inserted at the center of each column drum held a rounded wooden centering peg (Fig. 47). The peg ensured the proper alignment of column drums but was not important structurally.

The Temple platform exhibits horizontal curvature, which is known in other ancient Greek temples.[77] At Nemea the center of the platform on the long sides is nearly 0.06 m. higher

[77] Virtually imperceptible deflections from true horizontal or vertical lines have been identified in Greek architecture and various explanations offered for them; they are interpreted either as errors in modem observation and calculation or as intentional measures to correct optical illusions which were expected to arise otherwise. See F. C. Penrose, An Investigation of the Principles of Athenian Architecture (London 1888) 22-24, 27-35, 36-44; and J. J. Coulton, Greek Architects at Work (Ithaca 1977) 108-12.

Fig. 48.

Restored Corinthian capital, from Hill The Temple

of Zeus at Nemea , Pl. XXIII.

than the corners. To prevent rainwater from collecting, the Temple platform slopes down gently from the walls of the cella.

Cella . The interior colonnade of the cella (see Fig. 46) was two tiered, running parallel with the north and south walls and returning across the western end. The lower order was Corinthian, the upper Ionic (see p. 71). The primary function of the superimposed columns was probably to help support the roof, for no evidence suggests that a gallery ever existed.

The free-standing CORINTHIAN COLONNADE had six columns along the sides and four across the western end. The columns, each composed of five drums, rose to a height of 7.49 m. including capital and base. The capitals (Fig. 48; see museum A 16, 18, 20, pp. 18, 71) are similar to those at

Tegea.[78] The surface of each capital designed to face the wall of the cella was executed less carefully than the others. The joint surfaces of the column drums are smooth (without anathyrosis ; the same is true of the exterior columns), and several bear traces of saw marks (see p. 135). The column drums have empolion cuttings similar to those found on the top surfaces of the Doric capitals, apparently used in both cases in the rotation of the blocks on a lathe during trimming and carving. (See museum A 138, discussed on p. 72, for an unfinished column shaft dearly worked on a lathe.)

The shafts of two columns have rectangular cuttings for tenons, which may have been used to secure metal screens. The position of the cuttings indicates that the screens rose to at least half the height of the shaft. The screens were probably placed between the columns at the rear (west) of the cella where they would restrict access to the adyton . The openings between the corner columns and the cella walls were probably dosed with narrow but solid walls, as suggested by a "peninsula" which extends the smooth area of the paving surface from beneath the column to the wall.

The IONIC UPPER ORDER followed the plan of the lower order on whose epistyle it rested. It was composed of a series of quarter- and half-round column shafts carved on the corners and the ends, respectively, of rectangular piers (see museum A 11 and 248, p. 7I). The quarter-round columns were placed at the corners, the half-round columns along the sides of the colonnade and probably across the western end, each one centered over the columns of the lower order. The volutes of the capitals were carved with deep grooves, the edges spiraling to terminate in eyes projecting from the capital (Fig. 49). This design would have made the most of the little light entering the upper part of the cella.

[78] Roux, L'architecture, op. cit . (n. 73) 362-68.

Fig. 49.

Restored Ionic capital, from Hill, The Temple of Zeus at Nemea , Pl. XXVI.

The WALLS of the cella and pronaos were composed of a toichobate (wall base) course raised 0.08-0.09 m. above the peristyle paving and 0.05 m. above the paving of the sides of the cella; orthostate blocks (some still in situ around the cella); plinthoi (rectangular blocks, many of them reused in the Basilica); and an epikranitis (a wall-crowning block with decorative molding) which rested on top. The interior orthostates of the cella walls were set higher (0.43 m.) than the exterior orthostates, corresponding to the different heights of the cella floor and the exterior peristyle floor. The exterior orthostates at both western corners were L-shaped, as were the wall blocks which rested on them. The last wall block placed in each course (i.e., the "center" block) had two parallel rows of horizontal slots resembling ladders cut at each end (Fig. 50). The block would have been lowered with crowbars cutting by cutting and fitted into place.

At the east wall of the cella on either side of the door were parastades , or wall returns, projecting over z m. into the cella. A pier attached to the western face of each parastade formed the eastern end of the interior Corinthian colonnade. The opening for the door between the parastades is 4. 16 m. wide. When the door, built of two wooden leaves, was opened, each leaf folded against its parastade . The parastade thus prevented the door from swinging too far back and protected the

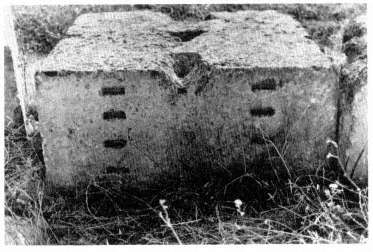

Fig. 50.

"Center" wall block with horizontal lifting slots.

interior colonnade from such swinging. Similar parastades were used in the Xenon (see p. 98), and the technique is found elsewhere as well (e.g., at Tegea and Bassae).[79] The design at Nemea, unlike those at Tegea and Bassae, effectively coordinated parastade and interior. colonnade.

The CRYPT at the rear (western end) of the cella is rectangular in plan (ca . 3.65 by 4.35 m.), with its four walls carelessly constructed of numerous reused blocks. The poor quality of the masonry suggests that the walls were faced with either stucco or stone veneer, although there is no evidence for either. At the eastern side, from the north, six steps (0.71 m. wide) descended into the crypt to a depth of nearly 2 m. The lowest three steps are preserved, the top two of which were

[79] For parastades at Bassae, see Roux, L'architecture, op. cit . (n. 73) Pl. I; for those at Tegea, see C. Dugas, J. Berchmans, and M. Clemmensen, Le sanctuaire d'Aléa Athéna àTégée ( Paris 1924) Pls. IX-XI, LXIII; see also IG II 1668.23-26 and 59, and the discussion of the term metopa in L. D. Caskey, G. P. Stevens, and J. M. Paton, The Erechtheum (Cambridge, Mass. 1927) 304-5.

carved out of a single block. A foundation wall of the Early Temple runs from below the steps toward the west wall of the crypt (see pp. 131-32). The crypt floor was paved with a thin (0.02 m.) layer of cement plaster which rests against the early foundation wall. On the interior faces of the two orthostate blocks of the cella wall immediately west of and above the crypt a curious raised panel has been carved, one not found on any other orthostate blocks.[80]

The function of the crypt remains a mystery. We may suppose that it enclosed an area of some religious significance. Where sunken adyta are preserved or recorded elsewhere, they are often associated with oracles (e.g., Temple of Apollo at Delphi).[81] The association of the seer Amphiaraos, one of the Seven who witnessed the death of Opheltes, with nearby Phlious (Pausanias 2. 13.7), although suggestive, cannot be considered evidence for an oracular cult at Nemea, which is, moreover, conspicuously absent from the literary sources.[82]

No fragments of the CULT STATUE , already missing when Pausanias (2. 15.3) visited the Temple in the mid 2nd century after Christ, have survived. It was probably located in front of the western columns of the cella. In the sanctuary of Nemean Zeus at Argos, Pausanias (2.20. 3) saw a bronze statue of Zeus which he attributed to the sculptor Lysippos of Sikyon, who was active in the latter part of the 4th century B. C.[83] It is

[80] See B. H. Hill, The Temple of Zeus at Nemea (Princeton 1966) 27-29, for discussion of both the northern limit of the crypt and the panels on the orthostates.

[81] Roux, Delphes, op. tit . (n. 73) 101-17.

[82] See L. Bacchielli, "L'adyton del Tempio di Zeus a Nemea," RendLinc ser. 8:37 (1982) 219-37, for an interesting recent study suggesting that the crypt at Nemea was intended for oracular purposes.

[83] Cf. Argive coins of Imperial times depicting a standing Zeus, nude, holding a scepter in his fight hand, with an eagle at his feet; the type persists virtually unchanged through several reigns and is thought to represent a copy of the statue by Lysippos; F. Imhoof-Blumer and P. Gardner, "Numismatic Commentary on Pausanias," JHS 6 (1885) 85, Pl. K: XXVIII.

tempting to suppose that this statue had been removed from Nemea to Argos when the games were transferred there (see p. 57).

The two Doric columns of the PRONAOS remain where they were placed more than two millennia ago, still supporting epistyle and frieze blocks (see Figs. 45 and 46). The columns, made up of twelve drums, are 9.55 m. high. The central epistyle blocks (parallel exterior and interior) are those preserved in situ . Contrary to the Peloponnesian tradition, the triglyphmetope frieze of the pronaos was undecorated (i.e., neither sculpted nor painted).[84] The extant frieze includes one block carrying a single triglyph and metope and the central block carrying a single metope (the last block to be placed; see the discussion of the exterior frieze, p. 139).

Exterior Colonnade . The DORIC COLONNADE (see Figs. 45 and 46) consisted of twelve columns along the flanks and six at the ends. Of these thirty-two columns a single example remains standing east of the southern pronaos column. Thirteen drums made up each column, which rose to a height of 10.33 m. The columns are noted for their slender proportions, a feature of late Doric buildings.[85] The column drums display a slight convexity (entasis ) in their taper, perhaps to correct the optical illusion of a concave outline which would be formed by a shaft with a straight upward taper (see n. 77). The shafts were carved with twenty flutes separated by sharp

[84] Roux, L'architecture, op. cit . (n. 73) 404.

[85] The proportion of column height to diameter is 6.34 to 1 and shows the tendency of the Doric column to grow taller and thinner over the ages. The 6th-century B.C. Temple of Apollo at Corinth, for example, has an analogous proportion of 4.15 to 1. By the 5th century the proportion of column height to diameter on the Parthenon in Athens had become 5.48 to 1. The thin proportions at Nemea have long been noticed by, inter alios , W. M. Leake, Travels in the Morea III (London 1830) 332: "The slenderness of the columns is particularly remarkable, after viewing those of Corinth; it is curious that the shortest and longest specimens, in proportion to their diameter, of any existing Doric columns, should be found so near to one another. The columns of Nemea are more than six diameters high, or as slender as some examples of the Ionic. . . ."

Fig. 51.

A lewis: a device inserted into a hole in the upper

surface of a stone block so that the block can be lifted

without damage to its finished exterior surfaces.

arrises. The lower side of the bottom column drums follows the gentle convex curve and slope of the stylobate.

The EPISTYLE blocks, each 3.75 m. long and paired back-to-back, spanned the distance from the center of one column to the center of the next. At the four comers of the building the interior epistyle had its comer joints cut at 45-degree angles.

The regular unit of the triglyph-metope FRIEZE contains a single triglyph and metope. The arrangement of alternating triglyphs and metopes and the centering of every other triglyph over a column required certain variations to the standard block (e.g., the comer block consisted of two triglyphs and an intermediate metope on its long face and a single triglyph on its short face). The block used near the center of both the flanks and the ends of the Temple consisted of a single metope; this type was the last frieze block to be lowered into place on each side of the building, and it alone shows a lewis hole (seen in cross section, with a lewis inserted, in Fig. 51), used for lifting and lowering.

The frieze backers were designed to rest against the frieze course and to support a peristyle ceiling. The preserved top surfaces, however, show no traces of a ceiling.

The CORNICE rested on and projected over the frieze course. The cornice blocks preserve two cuttings, which were used to secure the wooden rafters of the roof (Fig. 52): sockets were cut on the fiat top surface of the blocks along the back edge and shallow depressions along the front edge with cuttings for long rectangular dowels. The bed of the socket is horizontal and does not follow the angle of the pitch of the roof. Thus it is unlikely that it held the sloping rafter. The combination of socket and dowel suggests the use of horizontal tie beams or ceiling joists (set into the socket) to restrain the ends of the rafters (doweled into the upper section).[86]

The austerity of the Doric entablature was tempered by the elaborately decorated marble SIMA (gutter) along its eaves (Fig. 53). Each block of the marble sima is symmetrically designed around a central lions head spout (used to throw rainwater clear of the building) and ends with a spiraling acanthus tendril (see museum A 3, 5 a-e, 6, p. 17). All the decoration is carved on the vertical face of the block; the bottom edge has a projecting fascia. The lack of a crowning molding on the sima is an Argive and Corinthian detail.[87] Palmette antefixes, also of marble, were placed into cuttings at the joints between sima blocks. The sima supported the tile roofing by serving as a brake against the gravitational force exerted by the tiles. Each unit spanned the width of two pan files and had at its center a marble cover file (actually the continuation of the back of the palmette antefix). Because neither comer nor apex

[86] Cornice blocks from Tegea appear to preserve identical cuttings. C. Dugas restores a rafter with a V-shaped end set into the socket and doweled: op. cit . (n. 79) Pl. XLIV. Cf. A. T. Hodge, The Woodwork of Greek Roofs (Cambridge 1960) 84-85. Hill and Williams's restoration of a horizontal tie beam seems the more likely interpretation of these unusual cuttings (which apparently do not occur elsewhere): Hill, op. cit . (n. 80) 15-16.

[87] Hill, op. cit . (n. 80) 19, n. 48; Roux, L'architecture, op. cit . (n. 73) 329.

Fig. 52.

Restored drawing of the exterior superstructure, from Hill,

The Temple of Zeus at Nemea , Pl. XIII: A = epistyle, B = interior

epistyle, C = triglyph-metope frieze, D = frieze backer, E =

cornice, F = horizontal joist socket, G = sima.

Fig. 53.

Restored sima, showing the marble tile stops carved from the same block.

sima blocks (these would have carried cuttings for akroteria bases if they existed) have survived, akroteria cannot be restored.

The PEDIMENTS (see Fig. 45), 17.92 m. long and 1.87 m. high at the center, consisted of three courses over 1.00 m. thick. No conclusive evidence for pedimental sculpture exists.

Wood construction between the rafters and the ROOF tiles is hypothesized on the basis of an inscription from the second half of the 4th century describing the arsenal of Philo in the Piraeus.[88] There, lath and boards held with iron nails and a covering layer were used as a bed for Corinthian tiles.

Corinthian terracotta tiles manufactured in the kilns south of Oikoi 6 and 7 were laid above this hypothetical wooden system for the roof of the Temple of Zeus at Nemea (see p. 168).

The entrance RAMP , (see Figs. 45 and 46) at the eastern end of the Temple was built after the krepidoma had been completed and met the top of the stylobate in a flush joint (as suggested by the incline of the surviving blocks). Characteristically temples of the Hellenistic period have such ramps; the Temple of Zeus at Nemea is the first of them.

Tegea and Nemea . Several striking parallels between the Temple of Zeus at Nemea and the Temple of Athena Alea at Tegea have been noted. Scholars have suggested that the design of both the sima and the Corinthian capital at Nemea were copied directly from those at Tegea and, furthermore, have assigned the architect of the temple at Tegea, Skopas, to the Temple at Nemea as well. Although the buildings share several features (some of which are shared in general by 4th-century temples), they differ significantly in overall plan and design. While a conscious effort at Nemea to adopt some of the forms used at Tegea is likely, it does not follow that the same architect designed the two temples. It seems more tea-

[88] IG II 1668.55-59.

Fig. 54.

Perspective drawing of the columns to be reconstructed in the first phase

of the Temple reconstruction project.

sonable to suppose that there were artisans who worked on both projects, quite likely repeating some techniques and styles.[89]

Reconstruction Project . A detailed study of all the surviving architectural elements scattered around the Temple (Fig. 5) was begun in 1980 with the objective of eventually reconstructing the building.[90] Fallen blocks were moved and recorded individually (measured, drawn, and photographed)

[89] See Hill, op. cit . (n. 80) 44, n. 107 for a summary of scholars who have argued that the same architect designed, or the same artisans constructed, the two temples. More telling evidence would seem to be the virtually identical method used for securing rafter to cornice block (see p. 144 and n. 86); structural details shared by the two buildings may have greater significance than stylistic details, which are more bound by convention.

[90] See F. A. Cooper et al., The Temple of Zeus at Nemea: Perspectives and Prospects (Athens 1983) 51-83.

and then placed around the Temple in fields grouped by type to facilitate retrieval during rebuilding. Once the fallen material had been cleared and the platform and standing columns studied, the original position of each block was located and new plans and restored elevations drafted.

In March 1984 reconstruction of the third and fourth columns from the northeastern corner on the northern side of the Temple began (Fig. 54). Ancient blocks were removed, cleaned, repaired, and replaced, and some forty-two new blocks of the krepidoma were quarried from the same quarry believed to have been used by the Temple builders (see p. 134), cut, and set in place. For economic reasons work was suspended in January 1985 with seven more new blocks still needed before the restored stylobate would be ready to receive the columns. In addition to the newly set blocks, the visitor will see several alongside the Temple, including repaired column drums in various degrees of preparation waiting to be reset.