Khartar Gacch Legends

Because of its putative time-depth, the Osiya legend might be considered the most "inclusive" account of Osval origin. From the perspective of Jaipur, however, the Osiya myth seems to recede into a nebulous background. In this city, the dominant influence is the Khartar

Gacch, and the most relevant Osval origin mythology emphasizes the role of this mendicant lineage in the creation of Osval clans. I will refer to this body of material as the Khartar Gacch legends. Because the Khartar Gacch did not come into existence until the eleventh century C.E. , the putative time frame of the Khartar Gacch legends is much later than that of the Osiya legend.

Lest we lose the thread of our overall argument, it must be emphasized that the Khartar Gacch legends stress, as does the Osiya legend, the claim of Rajput/Ksatriya origin for most Osval clans. In a history of the Osval caste that adopts the Khartar Gacch perspective (Bhansali 1982; see chart on pp. 217-22), out of the eighty-one major clans listed, a total of sixty-five are (by my reckoning) traced to Rajput/Ksatriya clans or lineages.[35] Six are held to be of Mahesvari (a business caste similar to the Osvals) origin, but the Mahesvaris themselves are said to have been Ksatriyas originally. The remainder (including two clans of Brahman origin) can be regarded as special cases that do not disconfirm the main trend.

These accounts may be considered to be expressions of a coherent general theory about the origin of the community of Osval Jains. This is a theory that was shared by most of those with whom I discussed these matters in Jaipur. Some were hazy about the specifics, but the general view that Osval clans were created when Rajputs were converted to Jainism by distinguished ascetics—mostly Khartar Gacch ascetics—was quite widespread (see Figure 12 for an illustration of this belief). The Khartar Gacch legends themselves are less focused on the origin of the Osval caste as a whole than on the separate origins of Osval clans. As articulated to me by Jaipur respondents, the underlying theory holds that the Osval clans were created by Jain monks. These monks then encouraged their converts to marry only their co-religionists. In this way, the exogamous clans became knit into the encompassing Osval caste.

In what follows I draw heavily on two volumes that were placed in my hands by knowledgeable Jains in Jaipur. One is a history of the Osvals (cited above) authored by Sohanraj Bhansali (Bhansali 1982). The other is a short anthology of materials on jatis (castes) and clans putatively converted by Khartar Gacch monks (Nahta and Nahta 1978). Each of these books brings together large amounts of material gleaned from traditional genealogists, and together they are a rich source of material on Osval origins from the Khartar Gacch point of view.

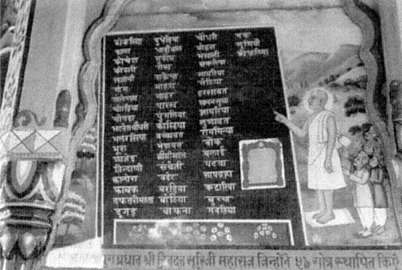

Figure 12.

Jindattsuri pointing to the names of clans created by him. Picture

on the wall of the dadabari at Ajmer.

The Quality of Miracles

A survey of these tales of conversion and clan formation reveals that thematically they are very much like the Osiya legend; the major differences are in the details. As in the Osiya legends, the theme of an ascetic's miraculous power is central. The convert-to-be, usually a king of some kind, finds himself in serious difficulty. A Jain mendicant overcomes the difficulty in a miraculous fashion, and the conversions follow.[36] The following examples will provide an idea of the range of the difficulties and miraculous interventions involved in these tales.

The difficulty is often the bite of a snake. For instance (this from Bhansali 1982: 67-72), the Katariya (or Ratanpura) clan came into being when a Cauhan (Rajput) king was bitten while resting under a banyan tree. Dadaguru Jindattsuri,[37] who just happened to be nearby, cured the king by sprinkling mantrit jal (mantra -charged water). The king offered him wealth, but Jindattsuri explained that mendicants cannot possess wealth. Jindattsuri then spent the rainy season retreat in the king's city (Ratanpur). The king came under the influence of his teachings, with the result that he and his family became Jains.

The miraculous cure of an illness is also a major theme. A good example is the story of the Bavela clan (ibid.: 117). The Cauhan king of Bavela suffered from leprosy. As in all these tales, no cure could be found. However, in 1314 C.E. , Sri Jinkusalsuri (the third Dadaguru) came to the kingdom and told the king of a remedy that had originated with the goddess Cakersvari (a Jain goddess). The remedy was tried, and in seven days the king recovered. He then converted to Jainism, and his descendants became the Bavela clan.

Another example of a clan originating with the cure of an illness is the Bhansali clan (ibid.: 149-50). This is in fact one of the most illustrious of the Osval clans. In the tenth to eleventh century a Bhati (Rajput) king named Sagar ruled in what is now the famous pilgrimage town of Lodrava (near Jaisalmer). He had eleven sons, of whom eight had died of epilepsy. One day, Acarya Jinesvarsuri[38] came to the town. The king and queen went to him and pleaded for him to do something to save their remaining three sons. Jinesvarsuri said all would be well if they gave the kingdom to one son and allowed the other two to become Jains. The king agreed, and Jinesvarsuri initiated the princes in a bhandsal (a barn or storage building), which is how the clan got its name.

Considering the warlike nature of the Rajputs, it is hardly surprising that victory and defeat in battle are issues on which these conversion tales sometimes hinge. An example is the story of the origin of the Kankariya clan (ibid.: 1982: 72-74). It so happens that in 1085 one Bhimsen, the Ksatriya lord of Kankaravat village, was summoned by the king of Cittaur. He refused to obey, and the king of Cittaur sent an army to fetch him. Bhimsen took the "shelter" (saran ) of Acarya Jinvallabhsuri,[39] who happened to be visiting the village at that time. The monk said that he would help if Bhimsen became his sravak (lay Jain). After Bhimsen had accepted Jainism, Jinvallabhsuri had a large quantity of pebbles brought. He rendered them mantrit (that is, infused them with the power of a mantra ), and, in accord with his instructions, when the Cittaur army came they were met with a shower of these pebbles. The invaders panicked and fled. The clan got its name because of the role of these pebbles (kankar ) in its founding.

The Khimsara clan began as a result of defeat in battle (ibid.: 76-78). In a place called Khimsar lived a Cauhan Rajput named Khimji. One day, enemy Bhatis plundered his camels, cows, and other wealth. With some of his kinsmen he pursued the thieves, fought them, and was

defeated. While returning to his village he met Acarya Jinvallabhsuri and told him the sad story. The monk said that if Khimji would give up liquor, meat, and violent ways, then all would be well. Khimji and his companions accepted. The monk then repeated the namaskarmantra according to a special method designed to subjugate enemies and then gave his blessing. Because of the influence of the mantra the mental state of Khimji's enemies changed; they begged for mercy and returned all their plunder. This story further tells of how these converts maintained marriage relations with Rajputs for three generations. But in the end, troubled by "derision" (whose is not clear), Bhimji (a descendant of Khimji) brought the problem before Jindattsuri when he happened to visit the village. The monk imparted his teachings, and then joined this clan to the Osval jati (caste). They then began to marry within the Osval caste.

The Gang clan (ibid.: 80-82) is another example of a clan created because of an ascetic's intervention in battle. Narayansingh was the Parmar (Rajput) ruler of Mohipur. There he was besieged by Cauhans. The Parmars began to run low on resources, and things looked grim. Narayansingh's son, however, reported that Acarya Jincandrasuri "Manidhari" was nearby, and suggested that this very powerful ascetic might help them out of their difficulty. The son disguised himself as a Brahman astrologer and sneaked through the enemy lines and came to the monk. The monk taught him the sravakdharm (the path of the lay Jain), and, on the son's promise that he would accept Jainism, repeated a powerful stotra (hymn of praise) for getting rid of disturbances. The goddess of victory appeared with a powerful horse. On this horse the son rode back to Mohipur. Because of the influence of the stotra , when the enemy army saw him they thought they were seeing a vast army that was coming to aid the besieged Parmars. They fled, and in the end all sixteen of the king's sons became Jains, which is the origin of the sixteen subbranches of this clan.

Some conversions result from a lack of male issue. The Bhandari clan (ibid.: 163-64) is an example. In the tenth to eleventh century there was a Cauhan ruler of Nadol village (in Pali district) named Rav Lakhan. He had no sons. One day, Acarya Yasobhadrasuri[40] came to the village. The king told him about his trouble and asked for a blessing. The monk said that sons would come, but that one of them would have to be made into "my sravak ." The king's twelfth son became a Jain, and because he served as the kingdom's treasurer (that is, keeper of the bhandar ) the

clan became known as Bhandari. A descendant of this son came to Jodhpur and settled in 1436. Previously this family had been known as "jainicauhanksatriya ," which means that they were Jains who were still Rajputs. At this point they became Osval Jains as a result of the teachings of a Khartar Gacch acarya named Bhadrasuri.

Conversion and Supernatural Beings

In parallel with a similar pattern that we have seen already in the story of Saciya Mata, in these tales the work of conversion is sometimes associated with the "Jainizing" or taming of non-Jain supernaturals. As Granoff points out (1989b: 201, 206), the ascetic in these tales often works his conversion miracle through the agency of a clan deity, usually a goddess, a theme that is certainly present in the Osiya materials surveyed earlier. "In these stories," Granoff points out, "monks are often powerful because they can command a goddess to do their bidding and aid their devotees or potential devotees" (ibid.: 201-2).[41] Granoff's survey of clan histories discloses another common pattern, that of the vyantar who is in fact a deceased kinsperson and who has come back to trouble his or her former relatives; the malignant spirit is then pacified by the monk and becomes a lineage deity (ibid.: 211). Most of these ideas are also present in the Osval materials I have surveyed.

For example, converts-to-be sometimes suffer from demonic possession. An alternative story about the Bhansali clan (this one from Nahta and Nahta 1978: 36) again focuses on King Sagar. One day a brahm raksas (a kind of demon belonging—the demon himself says in the story—to the "vyantar jati ") afflicted his mother.[42] Nothing could induce it to leave her. Finally, in the year 1139, Acarya Jindattsuri arrived in Lodrava and was asked to remove the demon. When he ordered it to go, it responded by saying, "The king was my enemy in a previous birth; I taught him about nonviolence, but this wicked devotee of the goddess wouldn't accept it and killed me. After I died I became a brahm raksas and I have come to destroy his family in revenge." The monk taught the demon Jain doctrine and made his vengeful feelings subside. The demon then left the mother, and Sagar became a Jain in the bhandsal as before.

In fact, the Bhansali clan seems to have had special problems with vengeful supernatural beings. According to another story (Bhansali

1982: 158-59; see also Granoff 1989b: 214-15), there was once an inhabitant of Patan named Ambar who hated the Khartar Gacch. When Jindattsuri's disciple came to Ambar's house to obtain food and water for the guru's first meal after a fast, Ambar tried to kill Jindattsuri by providing poisoned water. At Jindattsuri's instructions, a Bhansali layman, who happened to be in the community hall at the time, mounted a hungry and thirsty camel to fetch a special ring that would remove the poison. When the ring was brought and dipped in the water, the influence of the poison abated. Then this entire unfortunate matter became known throughout the city, and the king summoned Ambar, who admitted his guilt. The king gave the order for Ambar's execution, but Jindattsuri had the order cancelled. After that, Ambar began to be called "hatyara " (murderer), and upon his death he became a vyantar and began to create various kinds of disturbances (updravs ).[43] He vowed that he would not become peaceful until the Bhansali line was destroyed. In the end, Jindattsuri thwarted this vyantar by waving his ogha (broom) over the Bhansali family ("parivar ," but apparently referring here to the entire Bhansali clan). This is how the Bhansalis acquired their reputation of being second to none in their devotion to gurus (guru bhakti , and referring specifically to devotion to the Dadagurus).

An example of the involvement of a goddess in the origin of a clan is provided by the story of the Ranka-Vanka clan (Nahta and Nahta 1978: 38-9). The two protagonists, Ranka and Vanka, were descended from Gaud Ksatriyas, who had migrated from Saurashtra; they lived in a village near Pali where they were farmers. One day Acarya Jinvallabhsuri came and declared that Ranka and Vanka were destined to have an encounter with a snake within a month, and that they should refrain from working in the fields. Despite the warning they continued to go to the fields, when finally, as they were returning one evening, they stepped on the tail of a snake. The angry snake pursued them, and they had to take refuge in a temple of the goddess Candika (a meat-eating Hindu goddess) where they slept that night. In the morning, they saw the snake still lingering near the temple. They then began to praise the goddess in hopes of eliciting her aid. The goddess said, "Because of the sadguru 's (Jinvallabhsuri's) teaching I have given up meat eating and the like, and you people must give up farming and become the 'true lay Jains' (sacce sravaks ) of Jinvallabhsuri." She called off the snake, told them that they would acquire svarnsiddhi (the ability to make money), and sent them home. Later, Acarya Jindattsuri visited that place and

Ranka and Vanka began to attend his sermons. They were "influenced," became pious lay Jains, and later prospered greatly.

The Jain goddess Padmavati is important to the story of the origin of the Phophliya clan (ibid.: 49-50). The story begins with King Bohitth of Devalvada, who founded the Bothara clan (a very well known Osval clan) after being converted to Jainism by Jindattsuri. At the time of his conversion, his eldest son, whose name was Karn, remained a non-Jain and succeeded his father to the throne. Karn, in his turn, had four sons. One day he was returning from a successful plundering expedition when he was attacked and killed. His queen then took her sons to her father's place at Khednagar. One night the goddess Padmavati appeared to her in a dream, and said, "Tomorrow because of the coming to fruition of your powerful merit, Sri Jinesvarsuriji Maharaj will come here; you should go to him and accept Jainism, and you will obtain every kind of happiness." The four sons all became Jains. They made an immense amount of money in business, and were assiduous in doing the puja of the Tirthankar. At the instruction of Jinesvarsuri, they sponsored a pilgrimage to Satrunjaya, and while on the way they distributed rings and platters full of betel nuts (pungiphal ) to the other pilgrims. For this reason the eldest son's descendants become known as the Phophliya clan.

Even the Hindu god Siva was once used by a Jain monk as an instrument of conversion (ibid.: 42). It seems that the Pamar king of Ambagarh, whose name was Borar, wanted to see Siva in his real form, but was never successful.[44] When he heard about Acarya Jindattsuri he went to him and asked if he could arrange such an encounter. The great monk said that he would arrange the vision, but only if the king agreed to do whatever Siva instructed him to do. The king agreed, and went with the monk to a Siva temple. Standing before the linga (the phallic representation of Siva), the monk concentrated the king's vision, and amidst a cloud of smoke trident-bearing Siva himself appeared. Siva said, "O King, ask, ask (for a boon)!" The king said, "O Lord, if you are pleased, then give me moks (liberation)." Siva said, "That, I'm afraid, I don't have in my possession. If there's anything else you want, then say so, and I'll give it to you, but if you desire eternal nirvan , then you must do what this Guru Maharaj says." After the god left, the king worshiped Jindattsuri's feet and asked how to obtain liberation. The monk imparted the teachings of Jainism, and the king accepted Jainism in 1058. His descendants are the clan called Borar, so named for their royal ancestor.