62—

Mme Coutanceau's Clinic:

Bordeaux, 30 August 1793

Much has happened these last two months to enmesh the midwife's family in the revolutionary fray. The Coutanceaus have somehow finally gotten their maternity hospice, assigned to them on the very day that Charlotte Corday stabbed Marat in his bathtub. France's situation in the international war has meanwhile been deteriorating. Valenciennes has fallen in the north, and Toulon in the south. Now, on top of the threat of foreign invasion, Marat's murder has initiated a purge of internal traitors and anybody else suspected of moderate views. Everyone must show total devotion to the patrie . The National Convention, exactly one week ago, called for general conscription, a levée en masse requiring all young men between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five to "report without delay to the chief town in their district where they shall train in the use of arms each day while they await the order to depart."[1]

The Coutanceaus' son, Godefroy Barthélémy Ange, a medical student and only seventeen, has studied with his mother and has dedicated himself to "the art of healing" since 1790. He has been working as a chirurgien externe at Bordeaux's Hôtel Dieu since 1792. This call to "rise up against tyranny" changes his life. He will respond to it even though he is underage and must lie about his years, stating on an official form that he is twenty-one when he enlists as a surgeon in the Army of the Western Pyrenees.[2] Does he do this out of a genuine sense of commitment? Or is it perhaps a gesture to prove the family's patriotism? Mme Coutanceau will later say that she

meant her son to become part of her teaching and birthing operation at the new hospital, but starting now he takes a very different course.[3]

Meanwhile, the senior Coutanceaus have continued to work feverishly. Somehow, almost miraculously, despite the lack of funds from the central government, they proceed to teach and train midwives year in and year out. The balance of power in the household is shifting in interesting ways. The annual Bordeaux almanac always advertises the courses, dominated now very much by Mme Coutanceau (fig. 13) rather than her husband.[4] The municipality has put her in charge of an extra pavilion in the Collège de la Magdeleine to use as a maternity ward. The General Council of the commune of Bordeaux officially established on 13 July 1793 a new "hospital for women where they may deliver and to which will be admitted without discrimination unwed mothers and the poor." The clinic, on the street renamed Fossés de la Commune, has twelve beds, and the city council "names the citoyenne Coutanceau director of this hospice and . . . her husband accoucheur ." The couple must apply their talent and patriotic zeal to the task of delivering babies, but also to keeping them healthy and strong "by supplementing mother's milk with another food." Despite the lamentable fiscal state of the municipality, a promise is made—3,000 livres for her, 1,000 for her husband—and Bordeaux will continue to provide them with free lodging, wood for heat, and candles for light.[5] Although the city cannot keep its word on the money, it continues to give the clinic its moral support.

A midwife established as founder and director of a permanent clinic is a historic first in France. Mme Coutanceau has far surpassed her husband in importance, fame, and administrative responsibility. Once he had written in his hand the letters she dictated, and she had been quite dependent on him.[6] Now this accomplished woman is the boss, and he her underling. Although he continues to work alongside her for some time longer, he will branch off into other businesses, taking over some émigré property for example, to earn extra money. Meanwhile, du Coudray's niece is well on her way to becoming another great, famous midwife. Her aunt's taste for success and recognition, inexorably transmitted to her over years of training but latent until now, has really kicked in. She is almost forty, as was her aunt when she left Paris, striking out on her own, deciding to be separate and strong.

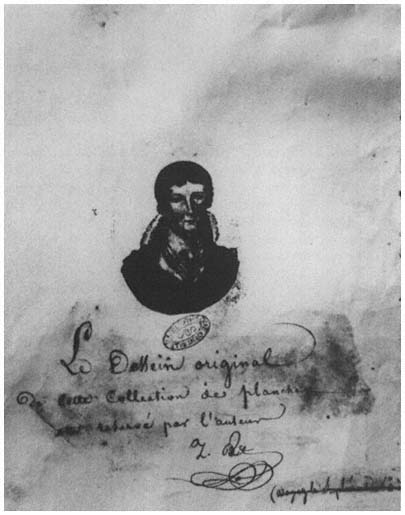

Figure 13.

This drawing of Mme Coutanceau is the only one of Mme du

Coudray's "niece" I have been able to locate. It is in an unpublished book

of illustrations by the Bordeaux artist Bouthenot in the Val-de-Grâce

Hospital in Paris. The printed volume, with planned engravings based on

these drawings, never appeared.

Photograph courtesy of the Val-de-Grâce

Hospital Library, Paris; may not be reproduced elsewhere.

It is not clear what role du Coudray plays in all this. Perhaps she is still healthy and dexterous enough to assist a bit with the teaching, or even to deliver babies privately for some extra money. Almost certainly she has been providing financial support for the household and clinic operations. Probably she has paid for everything. How else could they have stayed afloat? There were no other sources of philanthropy. The niece, as we saw, claims not to have been paid a single sou from Paris in the last three years, and Bordeaux, gallant intentions notwithstanding, cannot make good on its obligations. But the grand old lady has kept the valuable gifts she collected during three missionary decades, and has probably been melting them down and selling them off for several years already. Although there is no direct evidence of this, what else explains how, in the absence of all promised pensions from either state or city, the Coutanceau enterprise continues to thrive?