The Genesis of a New "Expressionism"

During the years 1913–1914 Corinth's pictorial conception began to undergo profound changes. As if to prove to himself that he could still handle even the most physically challenging assignment, he executed at this time a set of wall decorations for the Villa Katzenellenbogen, at Freienhagen, near Berlin, comprising ten large tempera paintings on canvas (B.-C. 567, 568, 571, 573, 609–614) illustrating episodes and individual figures from Homer and Ariosto. In these paintings, as well as in the preliminary drawings he made for the project, he continued to strive for anatomical accuracy and complicated fore-shortened postures. Similar in conception and execution are several contemporary paintings of the female nude (B.-C. 561, 562, 564, 566) as well as the

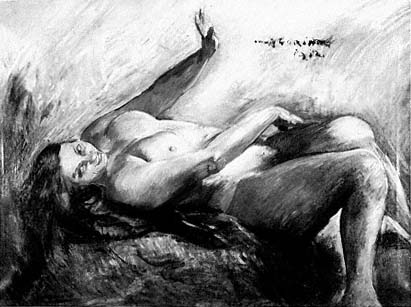

Figure 131

Lovis Corinth, Potiphar's Wife , 1914. Oil on canvas, 107 × 148 cm, B.-C.

605. Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt

(on loan from a private collection).

composition Ariadne on the Island of Naxos (B.-C. 569). The two versions of Joseph and Potiphar's Wife (B.-C. 606, 607) from 1914, in contrast, announce a different approach. In the preparatory painting in Darmstadt (Fig. 131) only Potiphar's wife is shown, reclining in an attitude of physical abandon. The brushstrokes, while simplified, emphasize the voluptuous forms of the anatomy; the heroine's lascivious gaze makes the viewer an unwitting accomplice in her amorous pursuit. In the two finished versions, of which the one in Krefeld may serve as a representative example (Fig. 132), the explicit eroticism of the subject has been subordinated to a much freer execution. The brushstrokes cascade downward from the upper right to the lower left, creating a suggestive rather than a descriptive ambience. Although the facial expressions and the anatomy of the nude are overspecific, even these exaggerations become bearable with the otherwise sketchy application of paint.

There is evidence that Corinth's drawings played an important role in his gradual acceptance of a language of form far less dependent on observation and description than heretofore. In one of the preliminary drawings for Sam -

Figure 132

Lovis Corinth, Joseph and Potiphar's Wife , 1914.

Oil on canvas, 77 × 62 cm, B.-C. 607. Kaiser

Wilhelm Museum, Krefeld.

son Blinded (Fig. 133), inscribed incorrectly in the lower right corner with the year 1913, Corinth heightened the expressive content by subjecting the anatomy to violent dislocations. The contours are not carefully controlled but torn. The widely spaced diagonal shading, freed from the necessity of modeling, respects the surface character of the sheet. Corinth did not apply the same simplified approach to the painting itself, however, but limited such formal explorations to the graphic medium.

In Ecce Homo (Fig. 134), a 1913 drawing in lithographic crayon and watercolor, description is subordinated still further to suggestion. The web of diaphanous lines is given only slight definition by the colored wash; and since neither setting nor groundline is indicated, the image rises mysteriously into the pictorial space. Unlike conventional representations of the subject, which usually objectify the episode entirely within the confines of the picture, Corinth's drawing forces the viewer into a real dialogue with the figures shown because it is the viewer whom Pilate addresses with his questioning gesture.

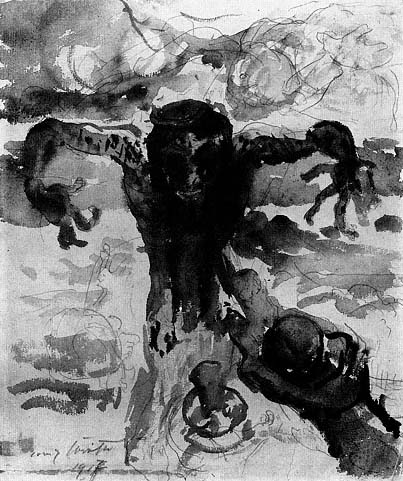

Figure 133

Lovis Corinth, Samson Blinded ,

1912. Crayon, 46.6 × 34.0 cm,

Staatliche Museen, Berlin (DDR)

(25/7826).

Figure 134

Lovis Corinth, Ecce Homo , 1913. Pencil and

watercolor, 33.7 × 25.4 cm, Eidgenössische

Technische Hochschule, Zurich.

Figure 135

Lovis Corinth, The Carrying of the Cross , 1916. Pencil,

25 × 35 cm, Kunsthaus Zurich (1935/25).

Photo: Walter Drayer.

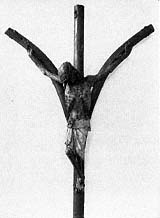

Figure 136

Lovis Corinth, Crucified Christ , 1917. Pencil and watercolor, 33.5 × 28.5 cm.

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (G 15.679).

Figure 137

Anonymous German, Plague

Crucifix, early 14th century.

St. Maria im Kapitol, Cologne.

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

There can be no doubt that Ecce Homo is yet another work steeped in Corinth's personal experience, part of his continuing effort to mythologize the events of his life in paradigmatic literary subjects. This personal component accounts for much of the drawing's formal audacity and meaning. Moreover, it was conceived as an independent work, not as a study for some painting or print. Among Corinth's paintings only two figure compositions suggest that he was prepared as early as 1913 to accept a comparatively sketchy execution as a "finished" work in that medium as well. One is the anecdotal Christmas Eve (B.-C. 577), a painting of Charlotte Berend in the disguise of Santa Claus presenting gifts to the Corinth children; the other is the so-called Small Martyrdom (B.-C. 558), which Corinth had begun in 1908 with the aid of a model strapped to a custom-made cross. In 1913, having added the figures of Mary, Longinus, and an executioner, he decided to sign the canvas, although it still retained the appearance of a preliminary oil sketch.

Corinth's development as a draftsman was not as consistent, however, as the above examples suggest. Indeed, in many drawings he reverted to his earlier academic conception. Not until 1916 did he explore more fully the departure from nature and the expressive handling of the graphic medium that distinguish the drawings Samson Blinded and Ecce Homo . The frieze-like composition of The Carrying of the Cross (Fig. 135) harks back to Martin Schongauer's famous print. But even though the architectural setting allows the drawing to be understood in terms of depth, real space has collapsed. The arch of the city gate in the upper left and the crosses of Christ and the two thieves are merely suggested by overlapping amorphous shapes that occupy the same plane. The contours of the figures have been negated by the blurring effect of the superimposed shading. Surface has begun to replace line; mass has been reduced to tone.

Corinth's development as a draftsman culminates in the watercolor drawing Crucified Christ (Fig. 136) of 1917. Here the horrid figure of Christ rises to the picture surface like a specter, virtually undefined in texture and mass. As in the Ecce Homo , the proximity of the frame propels the image into the viewer's space and consciousness. Removed from a larger narrative context, like the terrifying German plague crucifixes from the fourteenth century (Fig. 137), this Crucified Christ is the very incarnation of physical and psychic pain.

Without completely abandoning his faith in visual experience, Corinth openly renounced the academic ideals of his student years and earlier career when he wrote in October 1917 to the editor of Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration : "The hastiest sketch done before nature has greater artistic value than the most conscientiously painted composition pieced together in the studio."[26]

That Corinth's development as a draftsman had brought him to this recognition is evident not only from the drawings themselves but also from their new importance in his work. By 1916 there is little difference in form or conception between a drawing such as The Carrying of the Cross and the two lithographs (Schw. L245, L246) and the etching (Schw. 263) for which the drawing was a preliminary study. Still more striking is the evolving reversal in the relationship of Corinth's drawings to his paintings. His earlier drawings were subordinated to the paintings, serving generally as preparatory sketches. And even when conceived as independent works, they never seriously challenged the prodigious output of his brush. From 1914 on, however, he sought to impart the expressive force of his drawings to his painting as well—though not yet to new works; instead he subjected earlier paintings to the dynamics of his new drawing style by turning paintings into prints. Earlier he had made etchings after a number of his paintings, but always with the intent of reproducing the originals fairly closely. Not until his drawing style had matured did he begin to impose the same expressive simplifications on the graphic repetitions of earlier paintings. Compositions such as Harem (see Fig. 94) and Susanna and the Elders (B.-C. 387), both typical examples of Corinth's earlier extroversive manner, were among the first of his paintings to be so recast (Fig. 138).[27]

Not surprisingly, Corinth's development as a draftsman is closely linked to his growing skill as an illustrator. His earliest illustrations, a series of marginal vignettes and full-page drawings for Joseph Ruederer's collection of short stories, Tragikomödien , were done in 1896. They were carefully prepared after many studies of the live model. He did not undertake his next illustrations until 1910, when Paul Cassirer commissioned him to execute twenty-two color lithographs for The Book of Judith (Schw. L54). These, as well as the twenty-six color lithographs for The Song of Songs (Schw. L82) from the following year, are still not true illustrations but are more akin to small-scale history paintings, rivaling rather than enhancing the text. They too are based on a large number of preliminary studies and, like Corinth's paintings at this time, emphasize complicated postures and a strong sense of plasticity. In these respects they differ sharply from contemporary illustrations by Max Slevogt, whose imagination took flight without the aid of a model. Slevogt's activity as an illustrator began on a large scale much earlier than Corinth's. His nearly 150 pen-and-ink drawings for Ali Baba , of which forty-four were published by Bruno Cassirer in 1903, are lively improvisations that blend, rather than compete, with the text, prodding the reader's imagination at every turn of the page. Corinth first achieved a comparable degree of spontaneity in 1913 with his

Figure 138

Lovis Corinth, Harem , 1914. Etching, 18.1 × 16.4 cm, Schw.

170. Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich.

Figure 139

Lovis Corinth, Count Durande and Francoeur ,

from Achim von Arnim, Der Tolle Invalide auf

Fort Ratonneau , 1916. Lithograph, 45.5 × 30.2 cm,

Schw. L269 V. Staatliche Graphische

Sammlung, Munich.

lithographs for episodes from The Thousand and One Nights (Schw. L140) and for "Le Connestable" (Schw. L143), a story from Balzac's Contes drolatiques . His real breakthrough as an illustrator, however, came in 1916 with the lithographs for Achim von Arnim's Der Tolle Invalide auf Fort Ratonneau (Fig. 139): these no longer look like individually framed pictures but appear to grow organically from the pages of the book.

Perhaps a renewed awareness of Max Klinger's views on the freer relation of the graphic arts to the world of nature helped to change the position of the drawings in Corinth's work,[28] for his paintings continued to show a similarly expressive distance from nature only sporadically. A third version of Joseph and Potiphar's Wife in 1915, for example, was cast in a deliberately controlled form (B.-C. 657). Only in 1917 do Corinth's paintings also begin to show a more consistent use of evocative color and form and a diminished reliance on pure observation.

The stylistic evolution of Corinth's late work is most readily documented in the numerous still lifes he painted beginning in 1912. As in the example from Bordighera (see Fig. 121), he initially aimed for sumptuous effects, with showy flowers in expensive vases, often juxtaposed with bowls of rare fruit and confections. The earliest examples still show the environmental context of the various objects, but beginning in 1915 (Fig. 140) space is increasingly neglected, and the objects are usually observed from above, so that they appear more randomly distributed across the surface of the canvas. Although the pears and apples in the Schweinfurt painting are modeled, the other elements of the still life lack textural distinction. Even the statuette at the upper right has little representational value and functions primarily as part of the pictorial structure. The colors, on the whole, are somber, and black has been used profusely in both the shadows and the ground. More genial in expression is the still life from 1916 (Fig. 141). As in the preceding painting, the downward view flattens the imagery, and black is again a major feature in the composition, although its effect is lightened by the cheerful hues of the Chinese figurine, the darkly glowing red of the lobsters, and the shades of white and blue that flash across the table cloth.

The evocative Still Life with Lilacs (see Plate 23), painted in 1917, helps to explain Corinth's new way of seeing nature. In it the tangible image, perhaps more overtly than ever before, was largely a pretext for revealing—in the process of painting itself—the inner meaning of the picture. In that sense Corinth approached the subject exactly like the Expressionists, who similarly were less concerned with resemblance than with artistic vision and who sought

Figure 140

Lovis Corinth, Still Life with Fruit , 1915. Oil on canvas,

55.5 × 70.5 cm, B.-C. 644. Sammlung Georg Schäfer,

Schweinfurt.

Figure 141

Lovis Corinth, Still Life with Buddha, Lobster, and Oysters , 1916.

Oil on canvas, 55 × 88 cm, B.-C. 664. Galerie G. Paffrath, Düsseldorf.

to penetrate appearances to lay bare the inner essence of things. The flowers are dissolved in a torrent of brushstrokes that follow the familiar diagonal direction from upper right to lower left. The entire surface of the canvas vibrates, producing an impression of restlessness and excitement that unifies the picture but does not allow the eye to focus on any specific detail. Light from the upper right falls on the flowers yet scarcely penetrates beyond the uppermost blossoms of the bouquet. Except for a few touches of bright red, green, and white, the flowers remain in darkness, as shades of somber green and purple are enveloped in strokes of deep black. Beneath the painting's blustering vigor one senses a profound disquietude and an awareness that decay eventually embraces all living things. Prodigiously wasteful in their splendor, the lilacs seem consumed from within and thus take on the character of a metaphoric image into which the painter projected the knowledge of his own physical frailty.

In his portraits, too—again more or less consistently only from 1917 on—Corinth adopted a similarly expressive pictorial structure. Most of these works (commissioned portraits are the exception among them) depict members of the painter's family and friends; and this private character most likely encouraged the greater freedom in conception and execution. Initially Corinth continues to emphasize verisimilitude, but optical truth yields increasingly to subjective interpretation. This is apparent even in the portrait of Wilhelmine from 1915 (Fig. 142), in which Corinth projected his own psychological disposition onto his daughter, then only six years old. The window, through which no light penetrates, and the back of the chair, echoing the posture of the girl's arms, enclose her and restrict her movement. Amid the vivid touches of color, the face, surmounted by the broad-brimmed hat, remains a center of calm. And only the face has been given definition; the rest of the body is simplified. This pictorial isolation of the girl's features also underscores her solitude. Gazing at the viewer with large, pensive eyes, she has no real contact with the toy she holds. Of the children's portraits of the modern period only Edvard Munch's famous painting Puberty conveys a more poignant impression of loneliness, although in the very different context of explicitly adolescent anxieties.[29]

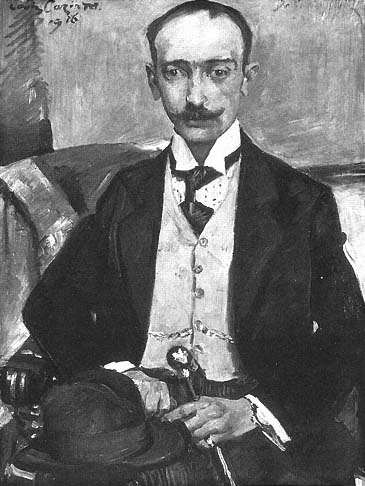

A more conventional conception governs the portrait of Karl Schwarz (Fig. 143) from 1916. Schwarz is seated quietly, his hat on his knee, his left hand clutching a walking cane. Corinth clearly did not record the sitter's fastidious appearance without a touch of irony. At the same time, he was sensitive to the sitter's inner life. Karl Schwarz averts his gaze, but the feverish glow of

Figure 142

Lovis Corinth, Wilhelmine with a Ball , 1915. Oil on canvas,

95 × 72 cm, B.-C. 652. Landesmuseum Oldenburg (LMO 13.328).

the eyes belies the placid demeanor, while the fashionable suit and accessories emphasize his frailty. Karl Schwarz (1885–1962) lived indeed in a constant state of delicate health. Employed as a reader for the publishing house of Fritz Gurlitt, he was completing his oeuvre catalogue of Corinth's graphics at the time of the portrait. The Milwaukee portrait itself originated in the context of this work, as did a second, more simplified but anecdotal, portrait from the same year, now in Aachen (B.-C. 666), which depicts Schwarz in the process of examining one of Corinth's portfolios.[30]

Figure 143

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Dr. Karl Schwarz , 1916. Oil on canvas,

104.9 × 80.0 cm, B.-C. 667. Milwaukee Art Museum Collection

(Gift of Thomas Corinth).

Photo: P. Richard Eells.

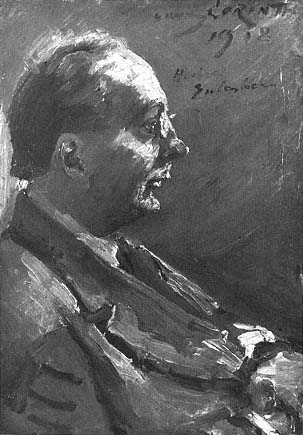

Figure 144

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Otto Winter , 1916. Oil

on canvas, 90.6 × 61.2 cm, B.-C. 668. Niedersächsisches

Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, Hannover (KM 23/1950).

The range of expressive possibilities that Corinth could summon up by 1916 is illustrated by his portrait of the Hannover pharmacist Otto Winter (b. 1855) (Fig. 144), an avid collector who owned several paintings by Corinth as well as works by the Expressionists, such as Kokoschka's famous 1914 allegory The Tempest (now in the Kunstmuseum, Basel). Although Corinth made Winter's head more prominent than his hands and torso, he nonetheless subordinated the facial features to the general effect. The sitter's expression is kindly, benevolent—in sharp contrast to the ominous picture ground, pervaded by an unpleasant sulfurous yellow. Furthermore, any sense of stability and emo-

Figure 145

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Herbert Eulenberg , 1918. Oil

on canvas on panel, 71 × 50 cm, B.-C. 732. Kunstmuseum

Düsseldorf (M 5307).

Photo: Landschaftsverband Rheinland/

Landesbildstelle Rheinland.

tional assurance is undermined by the labile character of the pictorial structure. The asymmetrical placement of the figure and the gravitational pull effected by the slashing brushstrokes introduce an element of transience that in one way or another informs all of Corinth's subsequent portraits. In the portrait of Herbert Eulenberg (1876–1949) (Fig. 145), for example, the writer who in 1917 published a short pamphlet on Corinth,[31] all the forms have become fluid. As if destroyed from within, the skin appears broken, and the darkest values of the yellowish ocher tonality that dominates the portrait seem to ooze through to the surface.[32]