Chapter 2

The Japanese Immigrant in New York City

In order to set the stage for this and subsequent chapters, I will briefly summarize the substantial differences between the New York Japanese and the Japanese on the West Coast. This profile, based on the majority of Japanese who registered at the Japanese Consular Office in New York during the 1910s and early 1920s, is crucial to our understanding some aspects of the preimmigrant's dreams about the United States. A thorough statistical analysis, including documentary figures, is found in the appendices and tables.

The Japanese migration to New York began in the 1890s and steadily increased through the first two decades of the twentieth century until it was abruptly halted by the U.S. government in 1924. Figures ranged from fewer than 1,000 emigrants before 1898 to more than 4,600 in 1920 (see Appendix 2, Table 5). Some arrived in New York after a sojourn in the West, often having worked their way across the country. Others sailed around Cape Horn or through the Panama Canal, traversed two oceans, and landed on the eastern shores of the United States in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, or Boston. Still others came via Cuba, British Columbia, or Mexico (see Appendix 2, Table 9).

About one-tenth of the New York Japanese came from the city of Tokyo or Tokyo-fu (urban prefecture) (see Appendix 2, Tables l, 2, 3). Almost 20 percent had urban origins, coming from the five major cities of Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, Kobe, or Kyoto. The rest were from the smaller cities and rural areas of the forty-six ken (rural prefectures) and

fu throughout Japan (see Map 1).[1] However, these figures alone are misleading, for between 1891 and 1920 government statistics indicated that 33 to 48 percent of the Tokyo population had honseki (registered family domiciles) in other ken. We can only assume, therefore, that the official figures underestimated the number of New York Japanese who came from Tokyo, for these figures did not account for individuals who were de facto, but unregistered, residents of Tokyo.

Socially, the New York Japanese were of the newly forming middle class or close to it. Almost three-quarters held hi-imin passports as opposed to imin passports.[2] Hi-imin were generally students, merchants, businessmen, and professionals and were required to have a middle school education or its equivalent. Imin, by contrast, were largely skilled or unskilled laborers, whom the Japanese government discouraged from emigrating to the United States. National leaders were responding to the barrage of verbal contempt Americans heaped upon Japanese labor immigrants, as well as the U.S. government's requests that Japan limit the emigration of laborers. Furthermore, they were anxious that the Japanese who came to the United States should represent their country in a way befitting citizens of a rising nation-state. In contrast to the New York Japanese, the majority of the Japanese on the West Coast were listed as imin.[3]

Males outnumbered females in New York as on the West Coast. When the Japanese government banned the emigration of picture brides in 1921, the number of passports issued to women bound for the United States as a whole decreased by 31.2 percent. However, in New York the number of women increased. In 1919 females constituted less than 8 percent of the New York Japanese population; in 1922, almost 25 percent. The majority of these women were wives of men residing in New York. This suggests that the Japanese government issued passports exclusively to wives of hi-imin and discriminated against imin wives of Japanese males on the West Coast.

In 1920 three-quarters of the Japanese males in New York ranged in age from twenty-one to forty, the majority being older than thirty. Less than 6 percent were twenty or younger. Half of the females were between the ages of twenty-one and thirty, leading us to conclude that they were probably young wives. This is in sharp contrast to the profile of Japanese immigrants in the United States as a whole, of whom three-quarters were younger than twenty-five when they entered the country.

On average, the Japanese who came to New York had received more education than those on the West Coast. Often they had been educated

Map 1.

Japanese prefectures. The underlined prefectures provided the greatest

number of Japanese in New York City (based on Appendix 2, Tables 1, 2,

and 3). Map adapted from Mikiso Hane, Modern Japan: A Historical Survey

(Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1986), p. 91.

in Tokyo or one of the other four large cities, where the major high schools, vocational schools, and public and private colleges and universities were located. The predominantly hi-imin and urban orientation of the New York Japanese suggests that, unlike the Japanese on the West Coast, they were primarily aspirants to the middle class (if not members already). They probably had more options in Japan as salaried or white-collar workers than those who settled in the West. But, like their counterparts on the West Coast, they did not want to remain in Japan at that time of their lives.

Japanese students and businessmen made up the largest group of arrivals in New York. Because people of that category, plus a few government officials (2.5 percent), constituted the majority of the population, the accepted notion is that they were not in the category of "immigrants"; rather, they were temporary residents, most of whom eventually returned to Japan. However, one cannot assume that they acquired an education or profited in business and returned to Japan. The evidence suggests that a large percentage did not maintain the status of student or businessman. Rather, they settled in the United States and toiled as unskilled workers.

When people decide to leave a familiar environment for an alien one, the unknown aspects of their future lives assume a quality of unreality and idealization. Negative stories they may have heard become forgotten or are disregarded, if temporarily. Fear plays an important part, of course, but when a person takes the first physical step of leaving old surroundings, it reflects a conviction that somehow the new will provide a better life. The Japanese who made the decision to go to the United States had the confidence that their quality of life would improve. For those who made the decision to go to New York City, especially those possessing a little capital and education, the possibilities seemed unlimited.

Reports from Japanese who had traveled to New York did not chronicle the endless violence and humiliation that Japanese on the West Coast experienced. The pioneering issei (first-generation) newspaper-man and historian of the Japanese in New York, Shozo[*] Mizutani, wrote that prior to the Sino-Japanese War, New Yorkers failed to distinguish between Japanese and Chinese and hounded "our compatriots who strolled in Central Park screaming 'Chinamen!' and threw stones at

them."[4] However, he continued, Japan's victory in 1895 brought a "closer relationship" between the two countries and "drastically transformed New Yorkers' views and feelings about Japan and the Japanese."

He described the following decade as a time of intense "perseverance and determination" for Japan, which sought to show the world that it possessed the capability and capacity to become a first-rate power. The Japanese consulate, which had occupied boardinghouses in Manhattan on West 9th, West 23rd, and near West 57th Streets, established its first formal consular residence in 1902 in an apartment on Central Park West.[5] After Japan's unprecedented victory over "formidable Russia" in 1905, the United States increasingly expressed "extraordinary friendship for Japan," and the people of the Atlantic Coast received Japanese nationals "with warmth and cordiality." New Yorkers, in particular, allowed the Japanese "to profit and enjoy recognition." Mizutani also noted that the Japanese goods exhibited at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair elicited such praise and admiration that after the close of the exposition, the leftover goods were brought to the East to be sold.[6] Additionally, New Yorkers proved their friendliness during the May 1907 visit of Gen. Kuroki Tamemoto Tamesada, a hero of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). The visit was recorded in exaggerated detail in Mizutani's history and hyperbolized in the magazine Amerika: "Kuroki fever in New York has risen beyond the boiling point! . . . New Yorkers respect his fighting spirit!"[7] The New York Times gave him front-page coverage and faithfully reported his every movement and his impressions of New York City, West Point, horse racing, and American women.[8]

Tobei publications expanded on the attractions of New York, which they portrayed as the ideal city for Japanese. A thirty-two-chapter geography of the city, illustrated with transportation maps and drawings, gave sketchy descriptions of buildings, banks, water and gas lines, land value and ownership, leases and contacts, J. P. Morgan, and housing.[9] Magazines and books covered topics ranging from a tailoring school to student life, employment, operating a restaurant, and the New York clothing trade (subtitled "The Success of the Jewish Immigrant").[10] These works never presented New York as a teeming, populated, dirty, busy city. There were no descriptions of small, crowded operations producing goods by independent and specialized processes, nor of the monopolization of jobs by particular ethnic groups depending upon the industry and the nationality of the entrepreneur or the foreman. Neither did these publications point out social and cultural distinctions

between the foreign- and native-born, the Anglo-Saxons and the southeastern Europeans, or the Jews and the gentiles, nor within ethnic or religious groups themselves.[11] One enthusiastic article characterized New York City as "an oddly international town" where people of many races lived "without conflict" and "became assimilated in an orderly way."[12]

Shozo[*] Mizutani began editing the newspaper Nyuyoku[*]shimpo[*]in 1916. Little is known about him except that when he took over, the paper enjoyed a dramatic increase in circulation and soon changed from a weekly to semiweekly.[13] One could assume that, given Mizutani's position as a newspaperman, resident of New York City, and trustee of the Japanese Association of New York, his history, Nyuyoku[*]nihonjin hattenshi, would provide valuable information about the New York issei. The details regarding population, geographic origin, age, and occupation are useful and important. Unfortunately, however, there is little that could help us construct an in-depth portrait of the hi-imin: the attitudinal lives of the majority of the New York Japanese, their perceptions about the United States before they left Japan, and the degree to which their expectations, dreams, and fantasies were realized.

Mizutani's history gives a one-sided picture of New York and the New York Japanese. The project was supported by and reflected the thinking of the Japanese Association of New York, a group of influential individuals. Japanese firms, banks, and merchants gave additional financial assistance. An office was provided by Dr. Jokichi[*] Takamine, a successful and active leader of the Japanese community.[14] Count Okuma[*] Shigenobu—twice prime minister, an advocate of empire, a supporter of Japanese-American trade and Japanese emigration to the United States, and a friend of the Mitsubishi combine—contributed the foreword. He praised New York as the center of American culture and finance, a place where Japanese could help create "a model society in North America" dedicated to education, technology, and trade.[15] The book's supporters and those who gave Mizutani source material and corrected the manuscript (he listed eighty-nine names in the introduction) occupied important positions in the New York Japanese business community.

Consequently, the promotion of Japanese trade and business in the United States was a major theme of the book—over one-third of its nearly 900 pages. It also included a brief historical description of Japanese-U.S. relations: the first Japanese governmental mission in 1860, when Japan was still under Tokugawa reign; American views of

Japan, including those of Commodore Perry and Townsend Harris; American opinions concerning the Sino- and Russo-Japanese Wars; a short ten-page "survey" of the Japanese exclusion "problem"; and biographical sketches of three noteworthy New York residents, including Takamine.[16] The permanent Japanese residents of New York, the majority of the community, and their occupations and institutions were given a scant 150 pages, or one-sixth of Mizutani's history.

Without question, Japanese on the East Coast did not encounter the virulent and continuous acts of hostility directed at Japanese in California, Oregon, and Washington. In those states yellow-peril xenophobia gave rise to the formation of the Asiatic Exclusion League, the San Francisco school controversy in 1906, alien land laws, racial incidents from Washington to Wyoming, and an exclusionary and fearful atmosphere for Japanese.[17] A writer in a New York Japanese immigrant newspaper, the Japanese-American Commercial Weekly, praised New York City in comparison to San Francisco: "San Francisco elicits hatred as when a samurai enters an eta [outcast] village. . .. The prejudices of the people of San Francisco . . . should burn and disintegrate like the houses in the recent earthquake. . .. New York is a mature and discreet adult compared to San Francisco which is a demon brat."[18] Another article, in Tobei shimpo[*] , described Seattle as being preferable to San Francisco but noted that New York welcomed Japanese "even more."[19] As Mizutani pointed out, New York's great geographic distance from Japan kept away the "swarms of Asians" that immigrated to the West, a blessing for those who chose to end up in New York.[20]

However, despite their insignificant numbers and the fact that the majority held hi-imin passports, the New York Japanese did not encounter the golden opportunities they expected as literate and educated people. Though they worked as menial laborers, saved some money, and learned English as suggested by the tobei publications, the world of socially valued work rejected them callously. In 1921, the year Mizutani published his history, 75 percent of the New York issei were engaged in domestic labor, a slight improvement over the 90 percent figure prior to World War I.[21] Given that increased U.S.-Japanese trade attracted larger numbers of Japanese business and bankers to New York, the actual number of domestic workers probably remained unchanged.[22]

The story of Toyohiko Campbell Takami (1875-1945) illustrates how one early immigrant overcame his beginning as a domestic worker.[23] Takami achieved success as a medical doctor with a private practice near Fort Greene Park, Brooklyn, and as chief of the

Department of Dermatology at Cumberland Hospital. His affluence eventually enabled him to own a summer home in Cold Springs Harbor, Long Island. With Jokichi[*] Takamine, Takami figured prominently in the formation and leadership of Japanese immigrant institutions in New York.[24] Born in Kumamoto-ken, he began classical Chinese studies at six and was sent to a traditional boarding school at age twelve. His father planned for his son to become a Shinto priest. However, Takami's own aspirations differed. He secretly attended a mission school because the "daily routine of Chinese literature, exercise and discipline began to wear on my nerves, and besides, I did not want to become a Shinto priest."[25] He was introduced to the English language, became intrigued by the story of Niishima Jo[*] , the Christian educator who stowed away to the United States on a whaling ship in 1864, and decided that his future lay in getting away from home and crossing the ocean, as Niishima did, to the United States.

During a vacation period, he set out on foot for Osaka, a journey that took him two months. Fifteen years old at the time, he planned to enlist the aid of a cousin and train to become a seaman. His cousin agreed and arranged for him to become a live-in domestic worker for a captain's family and to attend navigation school. However, Takami grew impatient and decided to look for a job on a ship. He hired on as a mess boy on a vessel that traveled between ports on the Japan Inland Sea. Finally, in March 1891, one year after leaving home, he landed a position as a captain's boy on an English steamship. "I bought the English National Readers and a Japanese-English dictionary . . . and started on a new adventure into the outside world."[26] The ship traveled to Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore, traversed the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, and the Suez Canal to Port Said, continued to Constantinople, touched Odessa in Russia, and arrived in Southampton, England, two months later. The captain and his wife hired him as their household worker until the ship sailed for New York, intending eventually to send him to navigation school when the ship docked. However, Takami wrote: "While I was very appreciative of their kind consideration for me, I had no intention of becoming a seafaring man. I had finally reached America and I intended to stay, at all costs, to get an American education as Joseph Hardy Neesima [niishima] had done before me."[27]

When he was allowed to go ashore in New York in October 1891, he "wrote a short note of appreciation" to the captain and his wife and left the ship. He headed for a boardinghouse for Japanese seamen near

the Brooklyn Navy Yard. "After a month of despair," he finally landed a job as a mess boy on an old navy ship. The chief steward and chief cook were both Japanese. The chief cook was "well-educated in Japan and had come to America to go to college," but like many of his compatriots he was unable to acquire enough funds to fulfill his desires. Befriended by him, Takami eventually became assistant cook and then, when his friend returned to Japan, chief cook. During this time Takami assiduously studied English and the Bible at a "Chinese Sunday School" on Fulton Street under the guidance of a retired college teacher, Nancy E. Campbell. Campbell took a special interest in him, and their close relationship resulted in his conversion to Christianity. Following her suggestion, he resigned from the Navy Yard position and moved to her home to enter high school. His educational career began in September 1893, when he left New York to attend Cushing Academy in Massachusetts.

Takami's life had taken a fortuitous turn at this time. Thanks to Campbell's interest and support in him, his ability to take advantage of her help, and his determination to fulfill his expectations, he attended exclusive Eastern schools and entered the medical profession.[28] During his summer vacations he worked as supply man and cook for the Department of Welfare's hospitals for underprivileged children and as a steward on furniture merchant John Sloane's yacht. However, these summer jobs, even though they were in the category of domestic labor, cannot be considered in the same vein as his earlier ones, for his wages went for books and clothing, not for everyday living expenses. He received tuition scholarships throughout his school and college years, and Campbell treated him as her own son.[29]

Takami's early work experience at the Navy Yard, however, was typical. A large number of Japanese men became domestic workers in New York City. In 1890-1891, over half of the 600 Japanese issei in the New York area lived and worked in Brooklyn. The Navy Yard was a sprawling center located east of the Brooklyn Bridge in Wallabout Bay, where the East River naturally widened. It housed work sections for specialized workers: blacksmiths, machinists, painters, plumbers, coopers, joiners, riggers, and others associated with shipbuilding. Their job was to repair and resupply U.S. Navy ships. The Navy Yard faced Park Avenue and Navy Street, and its workers populated the narrow streets close by on York, Prospect, Sands, Concord, and Gold.[30] The Japanese congregated in this area not to blend in with the crowd of semiskilled and unskilled laborers but to take on particular domestic jobs as kitchen

workers, stewards, mess boys, or cooks in the Yard or on the battleships.[31] Significantly, the Navy Yard was the one and only place in New York to which they could go knowing that other Japanese would be working there. Other than at the Yard and in Japanese-run businesses, they found work in scattered and isolated places.

Of the remaining 300 issei who lived in Manhattan, approximately 50 were government officials, business representatives, or small business owners. The rest worked as domestic workers.[32] Like Takami, many early Japanese immigrants had sailed to New York as cabin boys or galley helpers on American ships, one of the first groups comprising thirty-two individuals hired during the U.S. fleet's Asian tour in 1881. Some came on commercial carriers and jumped ship in New York harbor. Their illegal entry excluded them from any official count, Japanese or American.

Toward the end of the decade, a number of Japanese workers in the U.S. Navy began to be released from service. They looked for work, seeking out the few Japanese "Brooklynites"—including boardinghouse and restaurant owners—who lived on Sands or Gold Streets.[33] One Tokujiro[*] Iwase, a native of Chiba-ken (near Tokyo), served the Navy from 1884 for more than twenty years and recommended more than 100 of his fellow Japanese as workers. He was released with a pension in 1907, the year the Navy enforced a regulation prohibiting the hiring of non-U.S. citizens.[34] At that time, the Brooklyn Japanese began to disperse, and the gradual exodus of people and organizations to Manhattan started. Although in cases such as Takami's domestic labor was a temporary condition, for the majority of Japanese in New York it became a way of life. Other avenues of employment were not open to them. The same situation held on the West Coast, where Japanese who did not work as agricultural laborers often became household workers or "school boys," young men who worked while going to school or saved to attend school at a future time.[35]

One anonymous individual, in strong contrast to Takami, suffered through the more typical Japanese experience. Relegated to domestic work, he went from job to job, experienced isolation and bitterness, and was unable to realize his original goal.[36] This young man, like others, dreamed about the United States, read about the "land of freedom and civilization," and decided that to be "honored and favored by capitalists in Japan" he had to acquire "new knowledge in America." After being investigated by the Japanese government and experiencing "a great deal of difficulty and delay," he was issued a student passport and finally embarked from Yokohama for Victoria, British Columbia.

His account, written (remarkably) in English, articulated the fear, anger, disappointment, loneliness, and feelings of servility that were common among "the army of domestic servants." He served as a house boy, launderer, cabin boy, kitchen helper, dishwasher, butler, and waiter in boardinghouses, homes, mansions, and yachts; traveling from Victoria to Tacoma and Portland and finally across the continent to New York City. Each time he carried the hope that moving to a different and larger city would lessen his disillusionment with the United States, a feeling that surfaced as soon as he touched Tacoma, a city with "muddy streets and the dirty wharf." His first domestic job was "uncomfortable and mortifying," full of "subduing . . . vanity and overcoming from the humiliation and swallowing down all the complaints, weariness and discouragement." Succeeding jobs brought the same indignities. Employers as well as fellow housekeepers and cooks could be intolerant and unreasonable. He recalled: "Sonorous voice from the cook of my slowness in peeling potatoes often vibrated into my tympanum."[37] However, he also discovered as time progressed that some employers were easier to work for than others—one woman even "arranged . . . not to have any company and very often . . . dined out" during his examination periods. The young servant "adored her as much as Henry Esmond did to Lady Castlemond."[38]

He finished high school with the intention of attaining a college degree, but with each successive job his desire grew fainter and less feasible. In addition, his studies in college differed substantially from those in high school:

Some say Japanese are studying while they are working in the kitchen, but it is all nonsense. . .. How often you are disturbed while you have to read at least three hours succession quietly. . .. [O]nce I attended lecture after I have done a rush work in the kitchen. It was so fired felt as though all the blood in the body rushing up to the brain and partly sleepy. My hands would not work. . .. [M]y head so dull could not order to my hand what professor's lecture was.[39]

The difficulties of working for a degree while earning a living at the same time effectively nullified his original rationale for coming to the United States.

Time, he observed, had a way of dulling the initial feelings of humiliation. Domestic work required "no honor, no responsibility, no sense of duty, but the pliancy of servitude" and served to deaden any sense of independence. "I have commenced to manifest the interest of my avocation as a professor of Dust and Ashes," he wrote: "Years'

husbanding of domestic work, handicapped and over-interfered by mistress, their [the servants'] mental agilities are reduced to the lamentable degree. Yet, matured by these undesirable experience, most of them are quite unconscious of this outcome, as little by little submissive and depending habit so securely rooted within their mind."[40]

Indeed, live-in work, which was more prevalent than day work for these men, prevented them from having control over their own living and working conditions and decreased the likelihood of their moving to more rewarding, self-motivated occupations. For such people, domestic service was a "prison." Social relationships with people outside of the workplace, which might lead to alternative avenues of employment, were difficult to initiate and maintain. Often an employer's fair treatment solidified the employee's loyalty to the extent that any semblance of independence irretrievably dissipated. The emotional attachment of a servant to the woman of the house in particular, as well as her concern about his health and ability to work, served to complicate the "unconscious servile habit of action." Sometimes his relationship to her developed into "adoration," as in the case of the anonymous young man and his "Lady Castlemond." In the servant's eyes, the employer's family gradually became his family, and a vision of any free and independent life faded.

The Japanese domestic workers elicited varied reactions from their better-established countrymen. In one tobei publication, the author of an essay on New York employment opportunities praised the desirable qualities of the Japanese in New York, "a majority of whom were domestics."[41] Contrary to the young man who wrote about disillusionment with housework, this author considered isolation positive because it gave workers time to read and study. "Japanese help" had the reputation of being clean, neat, sober, earnest, strict, and industrious, qualities that encouraged clubs and families to hire them. The work of a cook, butler, or houseworker was presented as uncomplicated. Furthermore, wages were attractive. Even without being fluent in English or having considerable work experience, Japanese servants could get higher wages than white servants.

The best way to save money was to work as a cook ("if you don't mind the grease"). "Plain" cooks easily averaged $40 to $50 a month. "Fancy" cooks could earn $75 or more. Noted the tobei essayist: "Western cooking is easy even for the novice. . .. Japanese cooking is tedious and difficult since each dish has to be flavored in the pot. Westerners always boil their food and take it to the table as is. . .. [E]ach

person uses salt, pepper, or something else such as a sauce, as desired."[42] As a cook one was fed and housed and did not have to purchase special clothing such as that required of a butler. Also, many Japanese took on accounting responsibilities in the kitchen, a duty that could have lucrative advantages. No other type of domestic work—housework, butler, valet, and general housework for couples—offered the benefits of a cook's job for saving money.

Butlers were generally in charge of the dining room and "could be looked upon as one notch above waiters," although duties and status varied according to the family. However, the ability to speak English was a prerequisite, as butlers usually had to answer the front door and the telephone. Many people coveted a butler's position because it was "clean," but the monthly wages, between $50 and $55, made saving money difficult. The butler had to spend more money on personal appearance. Nevertheless, the most rewarding aspect of this work was that by "heeding each action, each move, each word, each phrase," at the dining room table, one could absorb much about American manners and personal relationships between spouses, parents and children, siblings, and friends.[43] General housework was the least desirable occupation and included "making beds, washing windows and bathrooms." "Anybody off the boat" could do it. It paid anywhere from $15 to $35 a month, a wide range.[44]

Significantly, the essay ended with an unanswered question—"What do Americans think of dishwashers whose native country won a war against Russia?"—implying that Japanese should be respected and deserved better jobs than domestic work. In the same vein, Mizutani pointed out that domestic work was clearly demeaning and should never be considered more than a temporary form of employment. It attracted only certain groups among the European immigrants—"the Irish and the Latins, first, and then the Russians and Italians, but rarely the English or French. . .. [T]raditionally, household work is labor with close ties to slavery. Even labor unions do not consider it legitimate. Therefore, it is not ideal for our countrymen."[45]

However, he conceded that for the majority of young Japanese in New York, "differences in race," inability to travel around the city, and ignorance of the English language prevented their working in factories or for transportation companies. He failed to mention that certain semiskilled or unskilled jobs were given exclusively to members of specific ethnic groups depending upon the industry, the entrepreneur, or the foreman, and that laws gave preference to native-born citizens over

aliens in certain public work. He complained that some Japanese with less than an elementary education were "like nomads," going from job to job without meaning in their lives. Their "peculiar characteristics" of "servility, idleness, and narrow-mindedness" hindered self-growth and thus the ability to change occupations. Others decided to come for a fixed number of years, intending to save money and then return to Japan. Of these, "nine out of ten" gave up their will to persevere and succumbed to drink or gambling. The "self-sacrificing" worked "as hibernating dragons in a pond" to save for an education or to set themselves up in business.

Citing an Imperial University graduate who achieved economic security in the United States, Mizutani stated his belief that educated people with the strength to surmount hardship were able to rise "above water level" within several years. However, others who completed high school in the United States while working as domestics could not secure a financially stable life. They lacked the skill to seek positions in U.S. firms or failed to enter into the small immigrant businesses, which could accommodate only two or three employees at most. Most Japanese firms, except for "one or two exceptions," recruited their staff in Japan, so Japanese immigrants in the United States were "shut out." Mizutani thus painted a dismal and pessimistic picture for the majority of domestic workers, including those who were educated and harbored aspirations and appropriate determination.

Leaders of the community attempted to alleviate the situation by establishing a special employment section in the Japanese Association during World War I; but, significantly, even though it was a time when employment levels were high, they lacked placement opportunities for Japanese and failed to devise an "appropriate" plan.[46] Regardless of their good intentions, they were unable to solve the situation. Their establishment of arbitrary standards regarding necessary and desirable character traits undermined the effort, as did their belief that the majority of domestic laborers lacked the wherewithal to lift themselves out of the kitchen. The harsh reality was that once an immigrant was forced to succumb to that work, change and success became elusive.

One other type of criticism of domestic workers appeared in the Japanese-American Commercial Weekly .[47] Japanese men in the United States were blamed as having "many faults similar to the faults of women." The author, an "anonymous woman," listed the desirable qualities in men—frankness, sociability, generosity, a forgiving nature, respectability, and reliability—qualities she found lacking in Japanese

men in the United States. An editorial comment following her piece explained that because many Japanese were domestic workers and supervised by women, they became "low and weak-willed," uninterested in acquiring the "strengths and merits of Americans." Instead, they were satisfied only with the superficial aspects of American life. Yuji Ichioka quoted reformer Ozaki Yukio as writing in 1888 that male domestic laborers developed "a maid-servant's servility" and that they were "a blot on Japan's national image."[48]

Toyohiko Campbell Takami also reflected these prejudices. When he returned to school in the fall after working during the summers, he noted that many of his white friends had spent summers abroad or at their vacation homes "in Maine or other places." "I am sure," he confided, "that I did not tell them I had spent my summer in the kitchen of the Floating Hospital."[49] This leader among New York Japanese implied that even operating a business related to domestic work was second-rate and undesirable. He wrote about an old friend from his Navy Yard days who prospered running a Japanese laundry in Brooklyn: "I asked him how on earth he ever got into such a business. He said that he had obtained a job in a Chinese laundry and learned all about the laundry business in a month. Now, he could do the work better than a Chinese laundryman. . .. I was very grateful that I did not come to America to be a laundryman."[50]

The stigma cast upon domestic labor and laborers by Japanese community leaders was confusing for a number of reasons. First, Japanese workers could not seek employment in the diverse small manufacturing industries that dominated the New York City economy. These provided job opportunities for the many immigrants from Europe even though they, too, spoke no English.[51] Japanese immigrants had no access to employment in the key productive sectors of the city's economy, such as the garment industry, building trades, or printing, or the many smaller, home-based industries, such as flower or candy making, shoemaking, or tobacco. Rather, the types of employment that were open to them or to which they congregated kept them isolated from the majority of the city's immigrants. They were not even on the periphery of the key industries. Their compatriots who ran specialized small businesses hired them, but these operations required only periodic help and paid little. Other immigrant businesses would yobiyoseru (call over) relatives or friends from their home area in Japan. Japanese firms and banks preferred to hire employees in Japan.

Second, being told that domestic service could lead to success and

then having to suffer its condemnations and humiliations served, at best, to legitimate disdain for the work and the workers and, at worst, to foster self-distrust and destroy confidence. The prophecy that domestic work robbed one of "manliness" was not difficult to realize. Such employment could serve to instill "unmanly" manhood, a stereotype sometimes used by compatriots as well as Westerners to describe Asian men. Also, it played on Japanese perceptions of gender and class, putting the Japanese domestic worker in New York in a state of perpetual subordination and inferiority.

Domestic workers constituted a substantial majority of the Japanese population in 1921, when Mizutani wrote his history. He estimated that approximately 500 of the little more than 4,500 Japanese in New York represented the government or Japanese firms or banks or owned small independent businesses.[52] The latter were scattered from the Navy Yard vicinity in Brooklyn to Cherry, Madison, East 19th, East 33rd, and West 123rd Streets in Manhattan. These businesses—import-export houses, wholesalers, boardinghouses, restaurants, grocery and general stores, tailor shops, photographers, and newspapers—catered in the main to the small Japanese population.

One of the more successful stores was Katagiri and Company, which still operates on East 59th Street in Manhattan. Katagiri also owned a vegetable and poultry farm on Long Island to supply his store and Japanese ships.[53] There were at least five Japanese tailors in New York, two of whom attended the Mitchell Sewing School, well known to tobei individuals because one of its graduates regularly advertised his "high-class" Tokyo tailoring establishment in Amerika. Judging from the addresses of the Japanese tailors in New York (Amsterdam Avenue; inside the McAlpin Hotel on Broadway and 34th Street; West 40th Street; and in the New York Times Building on Broadway and 42nd Street), they probably catered to white Americans as well as Japanese.[54]

The first Japanese-language newspaper was published in Brooklyn by a Japanese student in 1897. The publication was short-lived; Mizutani stated that a majority of Japanese could keep abreast of current news through regular English-language New York newspapers and magazines, so the vernacular newspapers could only "fill a minor news deficiency."[55] The Japanese-American Commercial Weekly (Nichibei shuho[*], later, Nichibei jiho[*]) began publishing in 1900, moved to St. Louis temporarily in 1904 during the international exposition, returned to New York, and was taken over by Takami and some friends in 1916. Nyuyoku[*]shimpo[*] , established in 1911, "competed on a par" with the Japanese-

American Commercial Weekly. Mizutani became its editor in 1916 and, beginning in 1917, published the paper semiweekly. Both papers ceased publication in 1941 with the outbreak of World War II. One of the problems of publishing a Japanese-language newspaper in the early years was the unavailability of type. In 1904 one newspaper, Nyuyoku[*]jiho[*] , arranged to print in Japanese using Chinese type, but the experiment failed. Both the Commercial Weekly and the Shimpo[*] imported type from Japan.[56]

The three Japanese churches in New York began as Christian boardinghouses in Brooklyn and Manhattan. The first, the Sands Street Mission, near the Brooklyn Navy Yard, was begun in 1894 by Kinya Okajima, a former California railroad construction worker and evangelist. Okajima walked across the United States to New York, was befriended by Takami, met Nancy Campbell, and began teaching at her "Chinese Sunday school." However, friction between the Chinese and Japanese "boys" led him to seek other avenues for proselytizing, and thus he established the first Japanese mission in New York on the upper floor of a seamstress's house. Two years later, aided by Campbell, the Central Methodist Church, and a Baptist minister, Okajima moved to larger quarters on Concord Street, and in 1910 he formally established the Japanese Methodist Mi-i Church at the Grace Methodist Church on West 104th Street in Manhattan.[57]

Yoshisuke and Barbara Hirose married in 1898, opened a Christian boardinghouse on Prospect Street, moved to East 54th Street the following year, and moved again in 1901 to East 57th Street. Their mission was designated the Japanese Christian Institute in 1913. The institute, under the leadership of Sojiro[*] Shimizu in 1914, grew rapidly and became the largest Japanese Christian church in New York.[58] At about the same time (1908), Ernest Atsushi Ohori[*] started a Christian boardinghouse with funds from the Reformed Church in America, established the Japanese Christian Association the following year, then moved to West 123rd Street, providing dormitories (one for women), a library, and meeting rooms. He retired in 1916.[59]

Boardinghouses that did not operate under Christian auspices and catered to Japanese workers in New York City often provided both lodging and food. Senzo[*] Kuwayama opened a restaurant and boardinghouse on West 58th Street in 1914 for men, mainly domestic workers.[60] It housed forty to fifty roomers during the busiest months and half that number in the summer, when the workers headed for resort areas in the mountains and at the seashore.

Boardinghouses served other functions besides providing food and lodging. At one time, Kuwayama tells us, part of his premises was used as a hat factory by an immigrant who was unable to find suitable work.[61] But its most important subsidiary function, as with many other Japanese boardinghouses, was to provide the physical space in which the men could enjoy leisure activity: "cards, dice throwing—in other words, gambling—which was an important source of comfort for them." Kuwayama rated success in gambling as a sign of "having guts," a necessary ingredient for achieving success. Unlike Mizutani, who complained that nine-tenths of the domestic "nomads" were inferior and worthless, Kuwayama saw all immigrants as courageous: "America seems like a place where the ambitious, the aggressive, the strong, and the competitive come together. It is a meeting place for people of many races and nations who have the strength to develop away from each of their old circumstances. . .. To survive in New York one needs extraordinary guts."[62]

Criticizing the attitudes of Japanese community leaders toward their less fortunate countrymen, Kuwayama also described the leisure activity of employees of Japanese banks, businesses, and trading firms. Most came to the United States without families and could join the exclusive Nippon Club, a privilege not enjoyed by most immigrants. However, the Nippon Club, like the boardinghouses, provided the space and atmosphere in which a person could relax and enjoy cards or plan for golf tournaments, which Kuwayama considered forms of gambling: "Under these circumstances, one begins to doubt the community leaders' calls for moral reform and social discipline. Gambling at the boarding houses is raided by the police and the unlucky domestic workers are considered criminals. Gambling at the Nippon Club is named a sport, recreation, pastime, or game for white-collar workers and looked upon as a natural form of entertainment. One can easily conclude that there is little difference between the two."[63]

This observation by Kuwayama illustrates the class distinctions between residents of the boardinghouses and their Nippon Club counterparts. The immigrant working-class population was defined as separate and unequal by the Japanese community and business leaders, as shown not only by Mizutani but also by Takami and writers in the Japanese immigrant press. Kuwayama, like Takami, began as a domestic worker but rose to open and operate the Miyako Restaurant, the only successful Japanese restaurant in New York City that catered to both a Japanese and white clientele before World War II [64] Like Takami, he also was

Fig. 1.

"Japanese Village, Luna Park," Coney Island. Photo:

Wemlinger (1903). From Brooklyn Public Library.

sympathetic to the plight of the Japanese domestic workers. The difference was that Takami led and worked through organizations established "so that no Japanese person would die a pauper's death or need to fear illness or adversity."[65] His low estimation of any work even slightly connected to domestic labor has been cited. Kuwayama, however, barely mentions community institutions in his autobiography. Neither does he minimize the worth of domestic work. Rather, he philosophically points out what he considered to be the contradictions between the leisure activities of the middle class and those of the working class. Kuwayama and Mizutani at either extreme, and Takami somewhat between them, articulated varying moralistic attitudes toward their notions of "immigrant behavior." These attitudes, also part of the thinking held by ideologues in Japan, were instrumental in the Japanese government's decision to differentiate between immigrants and nonimmigrants, as we shall see in the following chapter.

One of the more unusual and successful businesses in which issei engaged was the operation of amusement concessions at Coney Island (see Figure 1). Mizutani wrote that this practice originated when an

enterprising man started a "Japanese tea garden" in 1896 in Atlantic City, New Jersey.[66] Hoping to attract more vacationers, he remodeled part of his concession and set up two tables for a rolling ball game.[67] The alterations succeeded beyond his expectations, and "swarms of customers" came, bringing "unforeseen profit." Because this business did not require a great deal of capital, Mizutani noted, it attracted a number of issei, including "more than ten" in "the summer pleasure area" of Coney Island, Brooklyn. Others also opened concessions at Rocks-way Beach, Brooklyn; Atlantic City, Asbury Park, Newark, and Cape May, New Jersey; and Philadelphia. The business was so successful that some Chinese entrepreneurs "passed themselves off as Japanese" and went into the business.[68]

Mizutani described Coney Island as a spot where "most New Yorkers who were lower than middle class customarily spent their leisure time." From spring through early winter, "tens of thousands of dollars" were spent on games, theater, swimming, eating, and drinking, providing "work and profit" for the Japanese.[69]

Nagai Kafu's[*] short story "Akebono" (Daybreak), originally printed in Amerika monogatari, recounts one night in the lives of Japanese workers at a Coney Island concession.[70] Kafu[*] calls the amusement area a place "exemplifying the coarsest scene of seething humanity which probably cannot be found anywhere else in the world." His vivid description combines the glittery ugliness and beauty of the place:

Using electricity and water, there is every conceivable huge, showy device which astounds the masses of people—so many different kinds that one cannot keep track of them. Some exhibits give a little knowledge about history or geography. There are also suspicious-looking dance halls; obscene vaudeville houses; spectacular fireworks displays. And on a clear night, when one goes across New York Bay on a river steamboat, the impressive illumination of the electric lights are like daybreak lighting up the night sky and the far-off high and low buildings across the water look like a panorama of a sea god's palace.[71]

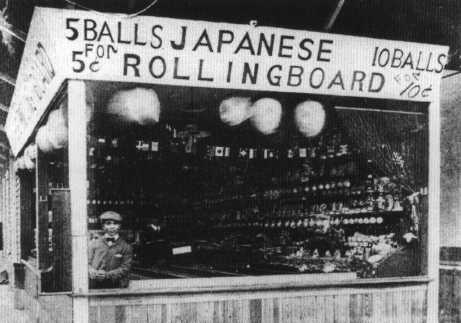

In the midst of this raucous fantasy world, "Japanese Rolling Ball" had the reputation of being "one of the most popular of all the games" (see Figure 2). However, its primary attraction was that one could "examine" a Japanese person, "a still unusual phenomenon"; winning the game and getting one of the prizes that crowded the rolling ball stalls was of secondary importance.[72]

Kafu[*] noted that the owners were generally men over forty who had left Japan after suffering hardship. In the United States, too, they had

Fig. 2.

"Japanese Rolling Board" from "Glimpses of Coney Island."

Photo: Blanchard (1904). From Kingsborough Historical Society.

luckless lives, went through "every experience," and reached the conclusion that "the world would get on some way"—that human beings did not die easily "even if they were forced to scratch at the earth."

Their faces have taken on the look of survival, of a boss, a brave warrior, a roughneck. And the people under them—the ones hired to count the rolled balls and to give customers their prizes—have yet to complete their life course in the world of failure. They are the unemployed who would be happy becoming the assistant boss or the young men who came to America recklessly thinking that they could work and study at the same time.

I was one of those workers and thought that it did not matter what I did. My only goal was to save money to go to Europe.[73]

According to Kafu[*] , it was a world where hi-imin and imin worked side by side. Their class positions did not determine their working conditions or wages.

The workers' wages at the stall where Kafu[*] worked were twelve dollars a week, less than at other stalls, which paid fifteen or sixteen dollars.

The owner bragged that his workers did not have to spend one penny for living expenses: "I give you three meals and besides, you can sleep in the store." Sleeping in the store meant that one was given a cot in the back of the concession, an airless receptacle enclosing the intense heat of the summer afternoons. Kafu[*] described one older man who at three in the morning, the end of the working day, took out a blanket, spread it on the wooden counter, and lay down. One of the younger men, who looked like a student, sarcastically remarked:

"Sleeping on that counter again? You'll dream well tonight.

"Who wants to sleep in the back? It's a nest for bed bugs. You should learn how to sleep on a board, too."[74]

The conditions in Kafu's[*] fictional account of the Japanese in Coney Island in 1906 are not far removed from those recalled by Haru Kishi, whose husband helped run a Coney Island concession in the 1920s.[75] Haru came to New York City as a young bride of eighteen. She came, she says, "to cook three meals a day" and clean for the workers who lived together above the concession in a wooden house. Ruefully, she remembers, "That was my honeymoon." Her life in the United States was not at all what she expected and totally different from her life in Japan.

Born in Tokyo in 1904 to a middle-class family, she remembers her childhood as being "carefree and happy." She attended a girls' high school, learned some English, and was influenced by a teacher's stories about how Japanese "should go abroad and see other people and other countries. . .. Sometimes he would close his lesson book and caution the class not to stay in small, crowded Japan, and I was captivated. . .. If it weren't for him, I might never have come to America." When talks began about marriage to Eikichi Kishi, "a businessman in New York," she expressed interest; not only had he been a longtime resident of the United States, but she thought he "looks nice," though he was more than twenty years her senior.[76] Her cousin, a Mitsubishi employee who was on a trip to Japan with Kishi, introduced them. "My parents were worried about my coming all the way to New York, but they found out that Kishi was a serious man and respected his parents. Our marriage was decided very quickly."

They met early in December 1921, Haru applied and got her passport the same month; their marriage took place on December 27, and on January 6, 1922, they embarked on a ship for Seattle. They crossed the continent by railroad.

We arrived in New York and I came to the summer concession, or rather, I was dragged into it. I was shocked and disgusted to learn that this was "the business."

I knew nothing about cooking. I never cooked in my life. There was a coal stove which I had to learn to use, a two-gas-burner hot plate, a wooden bathtub in the kitchen, and I had to cook for all those people. At first I just put the meat on the burners. Nobody told me what I was supposed to do. I was the only woman among fifteen men, sometimes more.

Work started around noon and continued until two o'clock in the morning: "My husband would bring the money upstairs and put it on the table to count. We had a mountain of money every night—I've never seen so much at once."

Haru's husband, Eikichi, "of good family," had come to New York in 1910 at the age of twenty-seven, planning to become a student. Unable to save enough money for school, he worked at various jobs and then became an assistant to the manager of one of the largest Japanese amusement concessions. It was during this time that Haru arrived in New York. She recalled: "Kishi was a scholarly type who hated manual labor and business. But he had to run the Coney Island 'skiball' game in the summer and work for a Japanese merchant in the winter. He was too poor to go back to start life again in Japan." He and Haru worked at Coney Island for three or four years, then ran a concession at Rockaway Beach and operated a small gift shop on Dyckman Street in Washington Heights, Manhattan, during the winter months. When the lease expired at the shop, business had reached a low. The early days of the Depression had set in, and the Kishis moved to Bayonne, New Jersey, to work at a year-round concession. But this also failed to prosper, not only because of the nation's economic slump: "During a presidential election year, I've forgotten which one, the police had to show how good they were and a big clean-up campaign took place. They closed the gambling joints and stuck their noses into everybody's business including the legitimate ones. All the Japanese 'bust up.' Our business wasn't affected, but since the other stores left, we also had to leave." The Kishis moved back to Manhattan, but their debts mounted; they could not pay the rent, were evicted, and had to move again, this time to a one-room apartment behind a laundry.

During those years Haru bore four of their five children. The first was born in January 1924, two years after she arrived in New York. Not knowing much English, she courageously entered a hospital, taking a dictionary, paper, and pencil to communicate with the doctors and

nurses. "I really don't know how I did it. It was very hard. I didn't know anything about childbirth. I was in the hospital for ten days. Kishi came to see me just twice. He said that the doctors were taking care of me. He didn't even tell my friends about the baby, so they didn't come either. I guess that's the way Japanese men are."[77]

Kishi got a job in Manhattan as a general domestic worker. Because it was day work ("he was away from six [in the morning] to nine [at night]"), he had only one afternoon off every two weeks. One year they began a lampshade store ("I don't know where Kishi got the money"), renting space from a fellow Japanese. "But when the business started to make profit, the rent went up, and someone else took over the store. It was taken from under us. So he had to go back to 'family work.' "

Their life changed somewhat after the youngest child entered school. They operated a small lampshade store; Haru made the merchandise by hand. The store was closed by the FBI in January 1942 after the outbreak of World War II, but customers continued to place orders, and Haru worked at home. Although most of their life in pre-World War II New York took place after the period of our concern, the constant moves, changes in jobs, financial insecurity, unemployment, and worry of their lives typified the experiences of earlier Japanese immigrants.[78]

Haru Kishi was one woman among fifteen men when she first arrived at Coney Island, not unusual among the Japanese in New York, where the average ratio was one woman to ten men. Her husband, fortunately, had been able to return to Japan to find a wife, an opportunity not readily available to the majority of issei men. An interviewee in the New York Nichibei in 1985 observed that the Japanese men in California could work hard, buy property, and marry a picture bride. They even had children and grandchildren. "But New York was a business town. Not only was buying property impossible, but getting a decent apartment was hard. You couldn't marry, either."[79]

The dream of meeting American women, socializing with them, perhaps even marrying one, remained a dream for most Japanese men. There were only eighty-two cross-racial marriages registered at the Japanese consulate between 1909 and 1921, a majority of the total during 1920 and 1921.[80] The Japanese male population of New York City, according to the official Japanese statistics, was more than 3,000 in 1920. Assuming that not all registered their marriages and that some unions were common-law (including, possibly, many interracial relationships), one could speculate that the percentage of married males in

New York was greater than the official figure of 2.5 percent. Nevertheless, that figure is far short of the national average of married Japanese males, which was about 30 percent in 1920.[81]

The story of Kinichi Iwamoto provides another example of how marriage was handled. Raised and educated in Nagoya, he came to the United States to continue his medical training.[82] Inspired by his father, who had lived in San Francisco for seven years and worked in a tobacco factory, and by an article in his high school bulletin, Iwamoto decided to come to the United States. After graduating from medical school in Nagoya, he secured a good job in a prefectural government office but wanted "to live independently in America, a good place where people could work and save money to go to school." Arriving in 1920, he worked in Tacoma at a sawmill for about six months, saving "a considerable amount of money." Iwamoto crossed the continent by rail to New York City and attended Columbia University for two years, working part-time in a research laboratory. He received his M.D. in 1923 and began his practice in 1924 on West 70th Street. Regarding marriage, he observed that Japan's ban on picture brides in 1921 made it impossible for the issei in New York to marry. He remained single until 1930, when he was thirty-five.

"I remember only about three Japanese women who were of the right age, but they had peculiarities and I was uninterested," he recalls. He socialized with an Irish woman for "two or three years," but "every time a female patient telephoned," she became "insanely jealous." Eventually he met and married a nurse of German extraction who worked at the hospital with which he was associated. They had two children and lived together until her death in 1961.

None of the surviving accounts regarding marriage—Takami's romantic story of meeting and marrying a Japanese woman studying at Mount Holyoke College;[83] Jokichi[*] Takarnine's marriage to a southern woman; the Christian minister Ohori's[*] returning from a visit to Japan with "a sweet young Japanese wife to help in his labor for souls";[84] Kishi's and Iwamoto's experiences—can be considered typical. Marriage procedures in the United States were not natural nor as free as men envisioned, and bringing a wife from Japan was expensive and cumbersome. I have not come across instances of picture-bride marriages in New York City, though some may have taken place. Those with some status in the Japanese community probably experienced less difficulty than the majority of men, who remained single. However, seeking and finding a mate did not come with ease for any Japanese

man in New York; even those mentioned were already in their thirties when they married.[85] Kishi was forty.

We can only surmise about the majority regarding their relationships with women. Nagai Kafu's[*]Amerika monogatari includes "Chainataun no ki" (An account of Chinatown), a graphic narrative of Chinatown's back-alley tenement slum area, "a showplace of the worst depravity, disease, and death."[86] The inhabitants had fallen so low that "it was impossible for them to sink any lower." In this environment Kafu[*] came across prostitutes who catered to Chinese and Japanese customers. In a run-down building occupied by Chinese:

Unexpectedly I came across a door on which a ribbon with a bow was attached, like a sign. The door opened halfway, revealing a thickly powdered American woman who peeked out as soon as she heard footsteps in the hallway. She called out to us using Chinese and Japanese words she had picked up.

. . . These women congregated here intending only to satisfy the animal desires of the Chinese—and of a certain class of Japanese, too.[87]

In the magazine Amerika, Katagiri Kuryo[*] also wrote about Chinatown.[88] He toured the city one evening with "a good-looking lively young man," Uemura, who was to leave the following day for a new job. Uemura took it upon himself to escort Katagiri, newly arrived and naïive, around the city and to celebrate his own departure. They stopped at bars along the way, each stop fostering greater camaraderie between the two men. Eventually they boarded the el. The writer did not know where they were headed, but his good mood thwarted any feeling of unease or ignorance. The train carried only a few people—a group of chattering painted women, "six or seven lower-class workers who are chewing tobacco," and four or five couples "sweet-talking among themselves."

. . . Occasionally Uemura looks over the women without saying a word, but finally he says:

"Hallo, girl."

"Hallo," one of them answers.

"How's business?" he asks, and crosses the car to sit next to the women.

I cannot hear what they are saying because the train is so noisy, but when he comes back to his scat he laughs loudly, "A-ha, ha, ha, ha!"

"Uemura! You're making a fool of yourself. You're disgracing Japanese! You're embarrassing me in public. . .. "

"A-ha, ha, ha, ha! Sorry! Sorry! . . . a green fellow like you doesn't recognize the animals you see over there. Those women are whores. They're going to work now. . .. [T]o them we're like gods."

They got off the el and came to an ugly and unruly bar in Chinatown.[89] A "dark-skinned Japanese" customer was speaking in "sloppy English" to a woman. Eventually Uemura arranged for Katagiri to be entertained by one of the prostitutes in the place. Katagiri, angry and insulted, fled. He ended his piece with the declaration: "I never met Uemura again. Promising young men like him get tainted by the freedom in America and surrender to reckless self-indulgence. Unconsciously they sink into the abyss of vice and sin."

The moralistic and superior tone of this piece implies that not everyone was equipped to take advantage of the freedom offered in the United States. Such liberty was detrimental to an upstanding character; it "tainted" some hi-imin types and led them to seek entertainment and pleasure in places where "dark-skinned Japanese" frequented.[90] Kafu[*] , fascinated by the slums of New York City, nevertheless expressed contempt for the "certain class of Japanese" who associated with people catering to Chinese. Racism, patriotism, and class biases are evident in the works of Kafu[*] and writers like him. However, the accounts are conspicuous for their descriptions of how individual men solved their inability to form relationships with women of whatever nationality. I am not suggesting that Japanese men would not have sought prostitutes had they been able to freely associate with women in the United States. However, I suspect that many did so because they, like the women they sought, were ostracized from the mainstream of work and social relationships.

Objectively, the Japanese in New York as a group had qualifies that could foster easy acceptance. They were not numerous. A segregated Japanese neighborhood never formed. A large number were educated, and some knew English. The Japanese government, adhering to the agreement with the United States, tried to control their movement and activity. Advice in the vernacular newspapers emphasized the need to live up to the image of a "civilized" population.

The literate and educated people who left Japan for New York thought life in the United States would not be difficult. They had absorbed some knowledge about the United States before departing: the careful lessons the tobei writers taught; articles in the self-help publications; the popular novels that mentioned the United States, its people, the West, and Western ways; and, of course, hearsay and stories heard from relatives, friends, and returnees. The immigrants combined information from all these sources to create a vision of the United States. Not all Japanese had the same vision, but their perceptions were generally positive. However, despite their backgrounds and the cultural

knowledge about the United States that they gathered in Japan, the majority of the Japanese who came to New York were unable to live up to the expectations and dreams they carried with them. Their work lives and personal relationships took unexpected turns. Without extraordinary perseverance, good luck, and the foresight to take advantage of situations and opportunities as Takami had, they faced lifelong bachelorhood, unskilled or semiskilled domestic labor, and an income that at best barely supported the comfortable, independent middle-class standard of living they hoped for.

Though the immigrant world presented obstacles, life in the preimmigrant world also had failed to fulfill the promises of a bright future for many of the educated and ambitious. Myriad changes in Meiji Japan created anguish, frustration, and disappointment among the youth: divergent understandings within families, at school, in the workplace, and in social situations; political upheavals, complicated by increasing bureaucracy that intruded upon everything from textbooks to passports and private political thought; and an overbearing state ideology that engendered patriotism, new class biases, sexism, and feelings of superiority over all Asians. These transformations spurred some to leave the country. Two significant forces helped shape an attitudinal basis for the decision to emigrate. One was the legitimation by the Japanese state of the essentially homogenized middle-class standards established for its population. In the government's emigration policy, these standards were exemplified by passport categories that explicitly differentiated between desirable and undesirable citizens as representatives of the country abroad. (The next chapter traces the evolution of the concept of hi-imin and its establishment as a passport designation.) The other force, the Meiji Japanese urban world, helped solidify the hi-imin image as an ideal toward which the citizenry should strive. Chapter 4 will focus on Tokyo as the example of the Meiji city, the hub of education, media, and government and a growing commercial sector. These two forces provided the framework in which visions of the United States became etched in the minds of those who were propelled to uproot their lives and move to another country. It is not far-fetched to surmise that those who reached New York carried cultural baggage loaded with these particular notions of their preimmigrant world.