Alpine Zone (11,500–14,246 ft, 3,505–4,342 m)

The vegetation above treeline is referred to as alpine (Fig. 4.4). In the White-Inyo Range, treeline generally occurs at elevations above 11,500 ft (3,505 m). In many

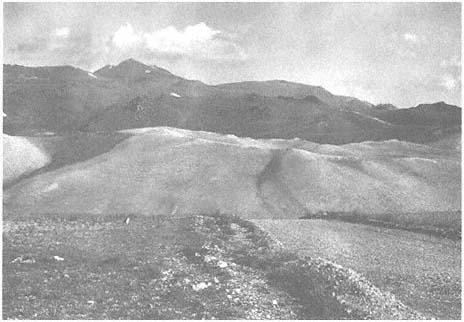

Figure 4.4

Alpine.

Photo taken on Sheep Mountain at an elevation of 11,600 ft (3,536 m). Note the

lack of trees at this elevation. White Mountain Peak (14,246 ft, 4,342 m) is in background.

Light areas on right represent moonscape-like dolomite barrens.

respects, the Alpine Zone in the White-Inyo Range resembles a high-elevation desert: solar radiation is intense, wind speeds are high, and evaporative water loss is severe. Since precipitation occurs primarily as winter snow, the only water available during the summer growing season is from melting snow and occasional summer storms. Other factors limiting plant growth in the summer are low temperatures, occasional frosts, and a short growing season.

Among the most distinctive areas of the White-Inyo Alpine Zone are the dolomite barrens. Viewed from a distance, the white landscape and apparent lack of vegetation give one the impression of a moonscape. Up close, however, small, loosely scattered plants are visible. Among these are Dwarf Paintbrush (Castilleja nana ), Cushion Phlox (Phlox condensata ), Raspberry Buckwheat (Eriogonum gracilipes ), and Blue Flax (Linum lewisii ).

On granite substrates above 12,000 ft (3,658 m), Alpine Fell-fields are common. The plant cover on these rock-strewn fields and slopes is fairly dense, sometimes covering all of the available soil surface. Important species include Mono Clover (Trifolium andersonii ssp. monoense ), Fell-field Buckwheat (Erigonum ovalifolium var. nivale ), Whorlflower (Penstemon heterodoxus ), and numerous grasses and sedges. Two of the more common grasses, Junegrass (Koeleria macrantha ) and Squirreltail Grass (Sitanion hystrix ), extend down into the Pinyon Woodland zone.

Dwarf Sagebrush (Artemisia arbuscula ) is widely distributed on dry, sandy soils. On talus slopes, the rocky substrate is unstable, and the soil is poorly developed; hence, the vegetation is quite sparse. Interestingly, three of the more conspicuous species present on talus slopes are restricted to elevations higher than 13,000 ft (3,962 m). These high alpine species are White Mountain Sky Pilot (Polemonium chartaceum ), Alpine Daisy (Erigeron vagus ), and Broad-podded Parrya (Anelsonia eurycarpa ).

The lower precipitation in the White-Inyo Range relative to the nearby Sierra Nevada results in a more open, less luxuriant vegetation. However, in areas of the White-Inyo Range where streams and ponds provide a source of water throughout the summer season, the vegetation can be relatively lush. In moist alpine areas, grasses and sedges predominate, particularly Tufted Hairgrass (Deschampsia caespitosa ) and Alpine Sedge (Carex subnigricans ). Meadow species with showy flowers that form colorful displays include Little Elephant's Head (Pedicularis attolens ), Meadow Mimulus (Mimulus primuloides var. primuloides ), and Alpine Gentian (Gentiana newberryi ).

A conspicuous feature of alpine plants is their prostrate growth form. By growing close to the ground, these plants gain shelter from potentially damaging winds. Plants with tightly interwoven clumps of leaves and a hemispherical shape are called cushion plants. Examples include Fell-field Buckwheat (Eriogonum ovalifolium var. nivale ) and Cushion Phlox (Phlox condensata ). Similar to cushion plants, but with greater lateral growth, are mat-forming species such as Mono Clover (Trifolium andersonii ssp. monoense ) and Whorlflower (Penstemon heterodoxus ). The close-knit foliage of these species counters cold nighttime temperatures by trapping daytime heat. For example, the interior of a cushion plant may be as much as 20°F (6.7°C) warmer than the surrounding air. Rosette plants, such as Alpine Gentian (Gentiana newberryi ) and Dwarf Lewisia (Lewisia pygmaea ssp. pygmaea ), represent a third prostrate growth form. These

plants have leaves that lie flat on the ground and receive direct sunlight as well as the added heat from the ground below.

Alpine plants tend to have well-developed root and/or rhizome systems. In fact, most alpine species have more of their biomass underground than aboveground. Along with absorbing water and nutrients from the soil, a primary function of the underground portion is food storage, particularly during the long winter season, when plants are dormant. Following snowmelt in late spring or summer, stored food reserves are used to initiate rapid vegetative growth. Because flower buds are generally produced one or more years prior to flowering, open flowers are commonly present shortly after vegetative growth is initiated each year.

For a number of reasons, sexual reproduction in alpine plants occurs infrequently. Flowers may fail to produce fruits and seeds due to limited resources, lack of pollination, or insufficient time prior to the onset of winter conditions. Low germination rates and high seedling mortality may further limit reproductive success. However, the ability of many alpine species to reproduce vegetatively and to persist for many years, once successfully established, may partially compensate for infrequent reproduction by seed.