PART SIX

SHANGHAI

42

A Time of Reckoning

(1923-24)

It was the last day of October when I started north. I traveled by the Blue Express, the same train that had been held up that spring by bandits, who took off a large number of passengers. All these trains had military guards. Later I heard a woman who had been on the same train with me explaining to friends how there had been special guards when she went north. I stopped off in Shantung and went up Tai Shan, one of China's sacred mountains. My only companions were the excellent Mohammedan chair bearers who make this trip their specialty, but I was very happy and enjoyed the day immensely.

I had looked forward for many years to visiting Peking. I stayed in the hospitable home of the Robert Galleys of the Y, and spent most of my time in sightseeing. I did things in a leisurely way, and had a private ricksha to take me about. But in spite of these precautions, one day I was ill; I kept feeling faint and my heart was bothersome. We called a doctor and he said, "heart over-strain." I must rest. Then our old friend, Dr. Morse of Chengtu, arrived in Peking for his own medical problem. He thought I should have a thorough examination and made an appointment for me with the heart specialist at the Rockefeller hospital, usually known as the P.U.M.C.[1]

During the examination I was told that I must enter the hospital at once. A dinner was being given for me that evening by an old Chinese friend of Nanking days, and I could not well be absent. The doctor finally agreed, if I would stay only a short time at the dinner and enter the hospital early the next morning. I followed his instructions, and the next morning saw me ensconced in a hospital room. Here I spent a month.

[1] Our family has many reasons to be grateful to the Peking Union Medical College (P.U.M.C.). Grace was there in 1923, Dick was treated for tuberculosis in 1936, our son Bob was born there in 1937, and my wife, Caroline, has been helped with bronchitis (the modern Peking complaint) as recently as 1984. Of course, it is now the Capital Hospital, but the taxi driver still uses the old abbreviated Chinese name, xiehe .

As soon as I "let go" in the hospital, I was like a wreck and, contrary to my usual nature, shed quarts of tears. The Austrian doctor in charge of that section of the hospital used to sit by my bed and stroke my hand, asking me where I suffered. I could not lie down, and lay there propped on a mound of pillows while the tears ran down my cheeks. Friends were thoughtful, and I had constant messages and gifts.[2] Legation friends supplied me with books, but life seemed hardly worth living. I had written Bob that I was going in "for a rest"; only Shanghai and Peking friends knew I was ill—and even I, myself, did not know how sick I was.

As soon as I could have visitors, I was much diverted by a Chinese of the Salt Gabelle, whom I had known as a young man in Chengtu where I used to teach him English.[3] He told the nurses he was my pupil and faithfully came to the hospital every day to see me. The nurses all became very friendly when they found I could speak Mandarin, even though it was the Szechwan brand. My friend was also visiting in the north and told me much of interest concerning his doings, the places he visited, and the things he was buying for gifts to those at home. In the Chinese way, gift selection was an important part of his journey; he even brought some of these presents to show me.

Doctors are often wary about telling patients of their ailments. They gave me no name for my illness; it was only later that I learned it. I had written Mabelle Yard and a few other friends in Shanghai that I was miserable, but Bob knew little of the truth. The heart specialist insisted on rest. I took little medicine, was not allowed to walk, had plenty of heart tests, and had X-rays of teeth and such things. Finally my kind Austrian doctor told me I would not be able to go to America by way of Europe. This upset me a good deal. I had assumed that after the hospital interlude I would be getting up and going about as usual. To relinquish such long-cherished and somewhat hard-earned plans seemed very hard to face, alone as I was in Peking.[4] I had to write to the shipping office to cancel the reservations, and also to Bob in Chungking.

I already knew what Bob's reaction would be: if we could not start for America as planned, he would choose to stay on in Chungking and help the new man get used to the work at the Y. But I still expected that we would soon be going to America by way of the Pacific.

[2] Grace, as would be expected, kept up her diary without a break. One of the visitors she noted was John Hersey's mother (also named Grace). Mr. Hersey's The Call (New York: Knopf, 1985) describes YMCA life in a different part of China—the north. The principal legation friends were UC classmate Julean Arnold and his wife (see chapter 3).

[3] Salt Gabelle was the usual foreign way of referring to the government's Salt Administration. All through Chinese history, a tax on salt has been an important revenue of the state. In 1913 the credit rating of the new republic was not high. In order to secure a large foreign loan, China had to agree to place the collection of this tax under foreign administration. "Gabelle" was a tax levied on salt in France before the French Revolution.

[4] Grace never was able to realize her dream of visiting Europe.

Although the doctors wanted me to stay longer in Peking, I was determined to be with the lads in Shanghai for Christmas. I was allowed to travel with a YW secretary who was going south, and had to promise that I would put myself in the hands of a physician as soon as I reached Shanghai. I did call a doctor the day after my arrival. He told me at once that I would have to spend eighteen hours a day in bed for the next six months.[5] This was blow upon blow. If it had not been for the Yards, I do not know what I would have done. The lads and I were there for Christmas together.

When our Y friends in Shanghai heard the word "endocarditis" and saw how ill I had been, they began to tell me that Bob would be down very soon. They entirely failed to understand our attitude. I prided myself on never interfering with any appointment or work of my husband. I would never send for him. If there were to be such a call, I expected it to be from the National Committee. The Committee, however, assumed that I would write urging him to come to the Coast. In the meantime, no full report of the seriousness of my condition reached him. I had the Yards' guest room with a private bath, and Dick was in a small study across the hall.

The year 1923 closed on a somewhat somber note. Though not athletic, I had always been very active. I rode and walked, though perhaps not as much as some. I had given up tennis because of my eyes. Now to be laid aside with severe physical restrictions for the future was devastating. I could not accustom myself to it; and I knew how disastrous it would seem to Bob. This was the truly unexpected. I thought of how I had been able to help Bob when his eye was injured, and felt that now I had failed him in my health. I was distressed that I would not be able to do as much for my family as I had done before. I knew I was going through a period of depression, but I tried to win back confidence and hope.

Life for Bob in Chungking had been having some different complications. Yang Sen and his forces started to retreat from Chungking the day after I had left that city. As is common in Chinese sieges, a gate was left uncontested for the retiring army. But Yang Serfs wives, who lived near us and had been so eager to call upon me that autumn, knew they might fare badly in a flight, and they rushed to our house in short order when the rout began. Indeed, inside of half an hour after the capturing troops entered the city, the former home of the Yang ladies had been thoroughly looted. Our faithful Lao Liu, the horse coolie, rushed to the Y to tell Bob.

When Bob reached the house, he found three or four wives with female relatives and servants of both sexes. The party was more than twenty in all. They had no interest in the upper part of the house. Fortunately, our ground

[5] Grace did spend a great deal of time in bed or resting, but her diary [or this period indicates that she found many needs to bend the doctor's eighteen-hour admonition.

floor was almost like a basement. Bob arranged several rooms for them there and also gave them the living room and study on the first floor.[6]

Bob often laughed about this experience. He had interesting talks with several of the wives' mothers. In 1927 Bob was in Hankow during a very tense period. One day an old Chinese dame in a ricksha waved, called, and made her puller stop. She was one of those mothers. She cried out with pleasure: "This is indeed good fortune to meet Hsieh An-tao. He helped us in Chungking four years ago and will help us again." The women were trying to get to Shanghai. Bob was able to send a Chinese to assist them.

When I learned in December 1923 that we would have to give up the trip through Europe, I was still in the hospital and could not conveniently send a telegram. I asked Mr. Gailey to send one for me. Bob knew I was in the hospital; when the telegram arrived and he saw the word Peking, he was afraid to open it. He took it home with him and kept it several hours before tearing it open. The change in travel plans was not the bad news he had feared! He then sat down and wrote me a beautiful letter telling me of his apprehension, and of his relief. He could not visualize me as anything but my old self. His letter took several weeks to reach me but was a great comfort.

Bob's replacement finally arrived in late January. Bob left at once and joined me in Shanghai in early February. I think he was surprised that I had been so ill, Actually, I have to thank him for sending me away from Chungking when he did. Had I remained, I might not be alive now.

Now that we were together, the next problem was our furlough. Because travel would be difficult for me, and I would not be able to keep house when we arrived in America, we decided to remain in Shanghai until the end of the boys' school year. The YMCA residences in Shanghai were impractical for me because the way they were planned required much climbing of steps and stairs. Jim and Mabelle Yard had a large ground-floor apartment. We were glad to accept their invitation to stay on with them.

Bob did some local work for the Y that spring and attended the annual YMCA conference in Hangchow. His Tibetan collection, which he had been accumulating for fifteen or more years, attracted attention and comment. He spoke about it at the American Women's Club.[7] I amused myself during those

[6] I believe that Yang Sen's harem stayed in our house for about two weeks and then left Chungking on a safe-conduct pass. However inconsiderate of human life the warlord generals might be where their peasant soldiers were concerned, they were usually considerate—and even chivalrous—when the lives of their rivals and their rivals' families were involved. Perhaps the kaleidoscopic nature of warlord politics reminded them that today's winner might well be tomorrow's loser.

[7] I think this was the origin of a Tibetan collection that Bob loaned to the museum at Shanghai Baptist College. The college was several miles below Shanghai on the Whangpoo River. During the Japanese attack on Shanghai in 1937, it was occupied by the Japanese army. Bob's Tibetan collection, and most of the contents of the museum, disappeared. The Japanese

agreed to pay the insured value, but that was lamentably low. Apparently, when Bob placed it there and was asked about its value, he had merely estimated his own cost of procuring the articles in West China. Financial affairs were not Bob's forte.

months in bed by compiling an anthology of Chinese poetry. It necessitated much reading, but I had plenty of time. And it was interesting to have some objective as I read.[8]

[8] The anthology was of English translations of Chinese poems. And that was the problem. Grace had a good working command of spoken Chinese, but she could not read. The nature of poetry, and the lack of any relationship between Chinese and English, mean that there can be as many different translations of a Chinese poem as there are translators. Which translation was Grace to take as "best"? It was a project that Grace would work on for a time and then put aside. Finally, in the late 1930s after Bob's death, she completed her manuscript. Her friend Pearl Buck suggested that she send it to John Day, the publishing firm that Mrs. Buck's husband was associated with. But their answer was negative. Grace's diary does not indicate that she tried anywhere else.

43

Unsettling Furlough

(1924-25)

We sailed from Shanghai on June 12, on a ship going to Seattle. When Y people returned from the field, the International Committee required them to have a medical check-up. Because of my health problems, we expected this to have special priority. But we assumed that it could wait until we reached California, where we would be staying with Bob's family. Unexpectedly, a telegram from the Committee insisted that we have the medical examinations before we left Seattle. The examinations were thorough and took several days—while we all had to stay in a Seattle hotel. The doctors were not pleased with my history or condition and thought I should not return to the Orient. It seemed hard to convince them that life for a housewife and mother might be easier in China where she could have all the servants that were needed. Still, we were both fairly optimistic and hoped for great improvement after I reached California.

The International Committee had told us that we would be living in Berkeley that year. As soon as we arrived, we started looking for a furnished house to rent, With three growing boys, it was not easy to find a suitable one. At last we advertised. This produced an attractive place on Spruce Street, not far from two of Bob's sisters.[1] That settled, I went south to spend three weeks with my parents. Bob took the boys to the old Service family ranch near Ceres, and then, with two of his elder brothers and two older cousins, on a fishing and camping trip to Tuolumne Meadows.[2]

[1] There were eleven siblings in Bob's family; eight reached adulthood, married, and had an average of three children apiece. His two married sisters near us in Berkeley had a total of seven, close in age to us boys. It was a great getting-acquainted of cousins.

[2] Toulumne Meadows was very different in 1924: narrow, unpaved, one-way roads; no specified campgrounds; not many people. My uncles went every year and always camped at the same spot on the bank of the Merced River. One of the uncles had an open touring car called the Apperson Jackrabbit. It was misnamed. First, a short circuit caused a minor fire under the seat. Then we broke an axle. I have been back to the Meadows many times, but that first time was the best.

30

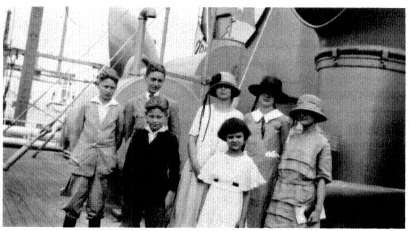

Seeing the family off on the ship at Shanghai in 1924. The four Yard girls

and the three Service boys. The NOW famous Molly is hiding under the

bushel at the right.

We all returned to Berkeley in August and settled into the Spruce Street house in time for the three boys to start school—in three separate public schools. The house was comfortable, with a spacious redwood-panelled living room and fine views of San Francisco Bay. We were also pleased to have a fireplace. But there had been a disastrous fire in Berkeley the year before, and the neighborhood was very nervous. As soon as we lit a blaze in our grate, the phone would ring: "Do you know that sparks are coming out of your chimney?" We had little joy out of that fireplace.[3]

Bob at once started to learn how to drive. As soon as he had a drivers' license, he bought our first car, a second-hand, 1922 Studebaker with a "California top." This made a touring car into a semi-sedan by adding sliding glass side windows. We enjoyed the car exceedingly, and soon felt the greatest confidence in Bob's driving.[4]

Bob also started to take some work at the University, but there were so many interruptions that he was unable to complete any course. For one thing, he was asked to give many talks. For instance, on one day he talked to the Lions Club at noon and the University YMCA in the evening.[5] The next day he addressed the University Meeting, and we had lunch with the acting

[3] There was another disappointment related to the fire hazard. I was astonished, coming from rainy Szechwan, to find that Berkeley has no rain from May to October—and watering the many flowers and shrubs surrounding the house was my assigned responsibility. In China, of course, we had a gardener.

[4] Grace, a non-driver, was being kind. I expect it is not easy to learn to drive at forty-five. But we all loved the car (Walnut Creek was a favorite, almost weekly, "drive in the country").

[5] Bob's name was kept alive on the Berkeley campus because the University YMCA (Stiles Hall) considered him its "representative in China" and staged an annual "Roy Service Day" to raise funds for his partial support.

31

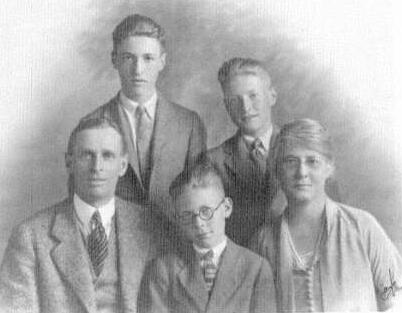

The family in Berkeley, 1924. The picture was memorable to Jack because

he had just persuaded Bob to let him don his first long pants.

president of the University. That same afternoon he talked to a women's meeting at St. Marks Episcopal Church. In the midst of this he had to go east to bring a Chinese friend, the president of the Chungking Y, across the continent. The friend, who spoke no English, had expected to travel via Europe with us. When our European plans were canceled, we arranged for him to travel with some Canadian friends. But they could bring him only as far as Toronto.

When we set up housekeeping, I tried to get on without help. This soon proved impracticable. The doctor told me to stay in bed in the mornings until nine or later, and I was not to do any kind of hard work. After several part-time arrangements did not work out, we got a maid. This pretty well solved the household problem.

In November Bob had to go to Southern California to make some speeches. Mrs. Strite, an old friend of the Service family, agreed to stay with the three lads, so I was able to go with Bob. We were back by Thanksgiving for a wonderful gathering of more than thirty members of the Service clan at Ceres. It was a jollification such as the Services well know how to manage. There were two mammoth turkeys and plenty to go with them. Singing and games ended the day.

Our own Christmas-present opening was in the morning around my bed. For weeks and even months Bob had been encouraging the three boys to hope for an electric train. The lads had each secured catalogues, and there had been hot debates over relative merits. As our gifts were opened on my bed, the parcels disclosed no trace of any train. When the air showed tension and disappointment, Bob remarked that there had been a lot of gifts on the bed, perhaps there was something under it. Immediately there were dives for the floor, followed by shouts and various signs of pleasure. It was the brand they had deemed the best, with extra track and equipment. That night there was a tree at the home of Bob's sister Irene, and our children had their only chance to share the fun of Christmas with cousins.[6] A few days later we were off to Asilomar, where a YMCA conference was to be held.

When we had rented the Berkeley house, it was with the understanding from the International Committee that we were to be there for the whole school year. At the end of 1924 we had word from the Committee that we were to move to New York early in January. This seemed an impossible feat to me. We were all nicely settled; to uproot the three boys from their school work when all were so well established and happy seemed unreasonable. Also, we feared that the doctors might not permit my return to China. If so, Bob would have to face a job hunt for Y work in America, and that would probably mean more moving. So we felt it best not to move the family at this time. As soon as we returned from Asilomar, Bob started off alone to New York.

After a few weeks, I had word from Bob that I had to go east and should make some arrangement for leaving the boys. Fortunately, Mrs. Strite was able to come again. Then my doctor would not let me travel alone! Finally, Bob came west to get me. On February 27 we left for Chicago, where Bob was to spend about four weeks. This gave me a chance to visit my relatives in Iowa.

Then we were off to New York. Here I found that arrangements had been made for me to enter a sanatorium in New Jersey. This was a place that took only "hearts, Bright's disease, and diabetes." We were pleasantly surprised to find a University of California classmate as head physician and manager.[7] He very generously arranged a large double room for me so that Bob could stay with me (he was able to commute from there to the Y offices in New York City). I was on a very rigid salt-free diet, with minimum fat and sugar. But the primary objective was tonsilectomy.

Because I had imbedded tonsils, they had not been entirely removed in 1916, and both had become infected. In Peking, Seattle, and later in Califor-

[6] it was Irene's collection of teacups that Grace had accidentally ruined in 1905 (chapter 2).

[7] The doctor was Fred W. Allen, UC 1902.

nia I had been told that they must come out; but no one was anxious to operate. Now, finally, with the most skillful anesthetist, with a clever throat specialist, and with our doctor friend (out of personal interest) in the operating room, I had the operation. I returned to the sanatorium for ten days and, at the end of April, was pronounced fit to return to China—but not to Szechwan. The doctors would not consent to my living where I would need to go to the mountains in the summer. And the Coast was thought to be better for me than the interior.

There had, of course, been consultation between the International Committee in New York and the National Committee in Shanghai. The National Committee had work for Bob on the Coast, and he would also be used for regular trips to the YMCAs on the Yangtze and in Szechwan. Bob felt that this would be in many ways an ideal arrangement. One of the chief problems in Szechwan had been isolation and the lack of two-way contact with the National Committee in remote Shanghai. If he were to be based in Shanghai and travel back and forth, he felt that this would be solved. On the day before we were to leave the sanatorium, he returned from the city full of happiness and thoroughly pleased with what he called a "surprise" for me. It was the news that our passage for China had been booked for August 22 on the President Pierce .

I knew the whole situation had been very difficult for Bob. He felt I had had too strenuous a life in China, and that it might be his duty to remain in America. He had been offered several Y positions in the States, but he always said to me that he had no place in America. He had given his life to China; he belonged to the China work. And, as the International Committee had stood behind us, so we must stand by the Committee. He did not speak of his ability to speak Chinese, or of his many friends there in China. He could not bear to give up in his forties the work to which he had turned his hand and heart when he was in his twenties. I agreed, and was as rejoiced as he to be able to return to the country and the associations so dear to both of us.

Practically all the thrill and excitement of near-normal American existence for me during that year in America was condensed into six marvelous days of May when we stayed at the Hotel Commodore in New York, saw old friends, shopped, went to theaters, entertained our niece Lynda Goodsell from Wellesley,[8] and stored up numerous memories that are still a source of happiness. We had a visit with relatives in Chattanooga, and two days with my parents in Southern California. In no time, we were back in Berkeley.

In the midst of "last things," Bob had his teeth pulled. We were closely scanning the newspapers those days for accounts of the "Shanghai Incident"

[8] Lynda was the eldest child of Bob's sister Lulu (see chapter 2, note 2). She had grown up in Turkey and would return there as a missionary.

32

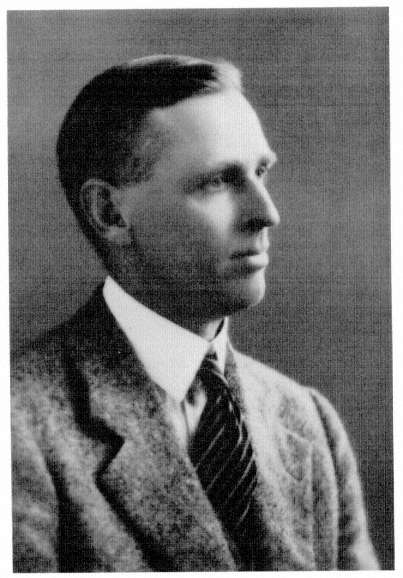

Bob and Grace on their furlough

travel to the East Coast, early 1925.

They look as if they knew that their

return to China had been approved.

of May 30, when foreign police in Shanghai had shot into a crowd of students and other sympathizers staging a demonstration in support of strikers in a foreign-owned textile factory.[9] Jack graduated from Berkeley High School in early June. He was still only fifteen and would return with us to China to work for awhile before going to college.

By mid-June we were with four other Service families camping together in Yosemite Valley. We had rented equipment; the others had their own. There were continual hikes, swims, and other good times. As soon as the men were back from any activity, a table of bridge would be started. If four players could not be found (very seldom), Bob and his elder brother Bert would sit down to cribbage, at which they were persistent foes.[10]

[9] The May Thirtieth Incident in Shanghai was seized upon by the Kuomintang and Communism, then in a united front, to galvanize the country against foreign imperialism. It was a milestone toward the Kuomintang's victory in 1927. For a time, the situation in Shanghai looked very uncertain, and Grace and Bob were scanning the news in the fear that their return might be affected. It will be recalled that their arrival in 1905 was also during a period of disturbance.

[10] Bob and all his family loved almost all games, and especially cards. This posed a problem for Bob in China. Missionaries were opposed to gambling. Chinese assumed that anyone playing with ordinary cards was gambling. So most missionaries avoided games with conventional cards. Our family went through a long, gradual transition. First, games with special cards: for instance, Old Maid and Rook; then Five Hundred; and finally bridge (auction and then con-

tract). After we went back to China in 1925, bridge was the order of the day. Grace was a good sport about all this. She lacked the Service zest for competition. She avoided "ladies' bridge." But she was willing to please Bob and her sons.

I rode on some of the excursions and picnics, but soon began to feel badly. It did not seem to be my heart. Bert's wife and I had gone into the Valley by train to avoid the elevation of the old road by Big Oak Flat (in 1925 there was no river-level motor road through E1 Portal). Finally, a day before we had planned to break camp, I had to leave. After I had spent a day in bed at Ceres, Bob arrived with our car and the boys and took me on to Berkeley. They drove me immediately to the hospital. I had an infected gallbladder, and a boil on a leg, and felt sicker and crosser than I can remember having felt before or since. For awhile I could eat nothing, and odors nauseated me. When they finally told me I would have to eat, the only thing I could think of that might be palatable was Chinese tea, which was not much of a food. Bob got some from a Chinese vegetable dealer. Gradually I added a dry cracker, a bit of toast, a taste of this or that—until eventually I was pronounced fit to leave the hospital.

All this time Bob was greatly worried. It was already July, and we were to sail for China in August. I wanted no guests at the hospital as I was actually too cross to talk—when that happens a woman does feel ill. But of course Bob came, usually twice a day; and always he asked whether the doctor had said anything about our return to China. I was thankful I did not have to report anything. The doctor knew our plans, and he never spoke of them at all. Neither did we.

Bob and the boys had moved into an apartment on Ashby Avenue, and our maid from the Spruce Street house came back to help out. As soon as I could travel, I went south by train (the doctor would not let me go by car). Bob and the boys joined me at Long Beach, where we took an apartment for a couple of weeks and visited with my parents. By August 10 we were back in Berkeley and busy with all the bustle of packing and last errands.

There was a great send-off by friends and relatives when we boarded ship on August 22 and started back to China.

44

Settling in Shanghai

(1925-26)

We had a pleasant voyage across the Pacific. There were various parties and the usual athletic contests.[1] Bob got out some of his Chinese hangings for the "Arabian Nights" entertainment and, dressed as a Chinese gentleman, took the prize [or "most handsome man." In Honolulu we hired a car and had a wonderful day. With swims both at Haleiwa and Waikiki, the boys were very happy. Our only regret that evening was that we so soon had to throw our leis in the bay.

By mid-September we were among friends in Shanghai. Bob left in early October for his first trip to west China on his new regional assignment. After he left we moved into a rented house at the end of Avenue Joffre.[2] With the younger boys at school and Bob away, Jack was my mainstay for the move. He did well until he developed a sinus infection and had to go to the hospital. When he was well again, he started working as an apprentice draughts-man at the architectural office of the YMCA. Several residences and Y buildings were being built around the country, and plans were being drawn for a new Foreign YMCA in Shanghai. Bob got home on December 24, just in time for the holidays. So ended 1925.

The new year started out to be a busy one. Bob was away in the West for three months in the spring and early summer. And I began to become active in a new way. I felt set free in Shanghai. After the long years when I had taught in the YMCA and at home, I was now entirely without that employ-

[1] My chief interest was in the table tennis tournament, which was won by Edwin O. Reischauer, later my Oberlin classmate and American ambassador to Japan. I was runner-up.

[2] The house we rented was in the same compound where Grace had been staying with the Yards in the spring of 1924. The Yards, however, had left China only a couple of months before we arrived back in Shanghai. Jim sympathized with the Chinese desire for more significant participation in the policy and administration of the Christian church in China. The mission considered him too radical and he was not returned to China. Mabelle continued to be Grace's boon companion—through a copious correspondence.

ment. In America I had seen many of my friends doing much in club activities; but I had never had a chance to do such things myself. Some years previously, I had become a member of the China National Committee of the YWCA. But living where I did, I had no opportunity to attend meetings or take any active part in its work. Now, in Shanghai, I became active on the Committee. I also joined several other organizations, among them the American Women's Club and the Association of American University Women.

Late in 1926 I became the chairman of the "Foreign Finance Committee" of the YWCA. This had charge of the allowances, living arrangements, and financial emergencies concerning the foreign secretaries loaned by various foreign YW organizations to the China National Committee. I continued as chairman for some years until the need for the committee's services were ended by a change in allowances and the decision to dispose of the YWCA residences.

When my mother heard that I had taken on this work, she was rejoiced and wrote that she was so glad that I was doing some missionary work at last! Nothing that I had done in Szechwan—keeping house amid difficulties, teaching, looking after children, entertaining many Chinese and foreign guests, doing everything possible to assist my husband's work—none of this seemed to her to come under the heading of "missionary work." I think she was probably embarrassed and bothered in her mind as to my worth or accomplishments. Certainly, she did not consider that work done by a non-denominational organization, such as the YMCA, had the true stamp of the missionary. As far as I can judge from what she said to me at different times, I remained an enigma to her as long as she lived. That I was satisfied without definite contact with a "Mission Board" was something she could not understand.

When we were in Szechwan, I once asked her to help educate a small lad (the son of our gateman), and she replied, "What good would it do? You are not connected with the work of the Church Board." She was an ardent Presbyterian, but in Szechwan that denomination had no missionary work; obviously, therefore, our work there was beyond the pale. She never helped financially in any way with the myriad benevolences crying at our door; to her, money for missions should go through the Presbyterian Board. No matter what causes I might espouse, nothing could move her from the rock of her sectarianism. I often wonder what my attitude would be if I had a daughter living in and trying to be helpful in a country like China. But I could never have the attitude of Mother's generation; I have seen too much in too many places, and I do not bow down in special reverence to any denomination. I want to be a Christian, and that suffices me.

We spent that summer in Tsingtao, on the Shantung coast. Bob was with us for his vacation, and Jack joined us for a short stay before going to sightsee

in Peking. We were out at Iltis Huk, some three miles beyond the city, and loved the quiet around the bungalows and the beautiful beaches. Bob took a trip to Chefoo with a Shanghai friend. There was still no real motor road connecting the two cities; this was the first time the trip had been done by car. I led a very quiet existence and was glad to rest after Shanghai's rapid pace.

My chief excitement was a weekly jaunt to the excellent market in the city. On one occasion I took a carriage, and in 1926 that meant an old vehicle of the victoria type. In color it was bright canary with a rusty black top. The driver was a man of ancient mien, clothed in flapping blue and black garments and wearing a tall, peaked straw hat. Under his feet he had a large sack of fodder for the two steeds; he could pick up a snack here or there, but they could not. After my visit to the market we added to the boot two live fowls of a somewhat disputative disposition, and two very large market baskets full to the brim with garden truck and fruit. Out of one of these stuck a tall beer bottle full of molasses, for thus did we buy that comestible. In our part of the vehicle we had groceries and a fish, a roast of beef, a roll of flypaper, and miscellaneous articles. Dick reported that a lot of people stared at us, but that did not worry me at all. We always enjoyed these market excursions but left other buying for the cook.

The autumn in Shanghai was occupied with a succession of house guests and the usual full program of city life. We became acquainted with more Chinese and several Japanese. I had Portuguese and German friends. Every acquaintance broadened one's horizons. And there were always unexpected happenings to swell the daily program and add tension to life.

One thing happened to me that autumn that I can never forget. A certain wealthy New York gentleman and his wife had been in Shanghai, staying at a hotel. We had met them several times. The annual YWCA funds campaign was in progress, and I was much concerned for its success. I knew this couple were interested in such activities, so I asked them for a subscription. I was surprised at the amount they gave. Indeed, they expressed themselves as delighted to help us and immediately invited us to dine with them the next day!

The mere idea of asking for money frightens some women. But all those organizations working to help people in need, and without finances of their own, depend on some one to raise money. I would never prefer such a task, but I have never shirked a part in the effort. I have collected funds for Red Cross campaigns, for churches, and for Christian Associations. But never did I meet such a warm reception, when a simple request for a worthy cause brought a generous check, a delightful dinner, and a most enjoyable evening.

There was a sad note late in the year: Jack, now seventeen, was preparing to go back to America for college. We planned for him to go by way of India

and Europe. He was to travel through Europe with the Heldes.[3] But as they did not want as long a stay in India, Jack was to go ahead of them on an earlier boat and they would catch up with him at Colombo. On December 6 we saw Jack off on a German ship. Half an hour later, Bob left on an unexpected trip to Hong Kong with Dr. David Yui, the head of the YMCA National Committee. Later that same day a cable from the International Committee in New York instructed the Heldes to return to America immediately via the Pacific. And Jack was already happily on his way.

Bob's ship was a fast one; he would be in Hong Kong before Jack. I cabled them both: they could discuss the matter and work out a solution. Bob cabled back: could I find any other couple or party to which Jack could attach himself? Several days of inquiries were unsuccessful. On the fifth day there was another cable from Bob. He had seen Jack off for Manila; the decision whether he should go on or come back to Shanghai was left to me: Jack would do whatever I said. There were dinner guests that evening, and I felt easier in my mind than I had for some days. Possibilities and probabilities chased around and around in my head all night. I remembered myself at seventeen, and knew Jack would be terribly disappointed if he had to return to Shanghai. It would be almost as if I told everyone that I did not trust him to travel alone. He had already started off to go alone through the Malay States and India. If he could do those alone, why not Europe? The next morning I cabled Manila, telling him to go on. As it happened, he managed exceedingly well. YMCA people in India helped. In Italy, he met by chance two University of California classmates of Bob's and mine.[4] Letters to friends from West China who had returned to England smoothed his way around Britain. I felt justified in my reliance on his judgment[5]

All during 1926 there had been much tension in China. The North and the South were at odds. Within a year of Sun Yat-sen's death in 1925, the Southern government had come under the control of the Left Wing, which was allied with the Russians and advised by Borodin.[6] Chiang Kai-shek,

[3] It will be recalled that George Helde's wife had died in childbirth at White Deer Summit in 1920 (chapter 33). He had now remarried, and his young son was with them.

[4] The classmates were Mary Irene Morrin and Katherine F. Smith, both UC 1902. They took me in tow through Italy. In Ravello we found ourselves staying in the same small hotel with Monroe E. Deutsch, vice-president and provost of the University of California—and also a 1902 classmate of Grace and Bob's.

[5] Grace's diary entry about this telegram to me has the brief phrase "Hugo helped me." So perhaps Mr. Sandor deserves at least part of my thanks for a fine trip. Perhaps, also, Grace— long thwarted in her own hopes to visit Europe—had some vicarious pleasure in giving me the go-ahead. Grace's diary is a succinct listing of each day's events, weather, letters received and written, books read, meetings attended, who won the evening card game, and so forth. But it is clear, from this instance and others, that in Bob's absences it was to Hugo Sandor that Grace turned for help and advice.

[6] Michael Borodin had spent many years in the United States, as had Sun Yat-sen. This made it possible for the two men to dispense with interpreters and to use English in planning China's revolution. While Borodin was orchestrating the campaign against missionary imperi-

alism, his wife and two Chicago-raised sons were living with an American missionary family in Shanghai while the boys attended the mission-dominated Shanghai American School. They were, of course, using a name other than Borodin.

though not entirely under Russian control, was leading the Northern Expedition against Peking. There was continual unrest and fighting throughout the Yangtze Valley. The fall of 1926 saw many foreigners concentrating in Shanghai. Consular officials, alarmed by unrest, antiforeign strikes, rioting, and fighting here and there, would not permit travel to the interior. Many missionaries were being urged to take early home leave; people returning from home leave were being held at the Coast, hoping for a time of less uncertainty. Our house was full of guests all that winter.

Early in 1927 the Left Wing set up a National Government at Wuhan (the three cities of Hankow, Wuchang, and Hanyang), and Chinese took over the British Concessions in Hankow and Kiukiang. Many foreigners were told to leave the interior. Their arrival added to the large numbers already in Shanghai. Many people from Szechwan were among them, and we did all we could to help. A British bank turned over a large old-fashioned residence for use as a hostel. It gave shelter to a number of our Canadian friends, but they needed furniture and other necessities. I took over a lot of curtains.

About the middle of February a British steamer arrived from Hankow with one hundred and fifty refugees from the West. The whole ship had been taken over for this purpose, including the space below decks that was normally occupied by Chinese coolie-class travelers. We were in the big crowd meeting the boat because we expected two girls [women] from the American Methodists. We found them at last in the bowels of the ship, where they had certainly traveled "hard."

After they reached our house, the first thing they mentioned was a bath. "Oh, yes," I said, showing them their bathroom across the hall. "This is for your use and no one will be sharing it with you. Here are towels and everything, so make yourselves at home." A little later I saw them floating about the hall and one murmured, "We were thinking of taking baths." "Certainly," I agreed, "I hope you have everything." She looked uncertain. I went on about my own affairs, and still later they again mentioned bathing. So I said, "Well, why doesn't one of you start in on a bath?" "But the hot water?" said one of them. I looked puzzled. "There is plenty," said I, "just turn on the tap." They shrieked and began to laugh. "We haven't seen a real American bathroom for such ages. . . . You know how in Szechwan we always have to get the coolie to carry in hot water. . . . Oh, Mrs. Service, what do you think of us!"

The Southern forces came into the Shanghai area in March. They took over most of the Chinese-controlled areas around the foreign settlements without incident. North of the city some Northern troops made an attempt

to fight and then tried to flee, with their arms, into the International Settlement. They were kept out by the Shanghai Volunteer Corps and other available units, but this involved considerable shooting. With the inflamed anti-foreign sentiment of the time, Southern agitators tried to distort this defensive action. The situation was very tense for about thirty-six hours. There was talk of a general strike by the servants of foreigners, but nothing came of it. Indeed, our servants appeared to be exceedingly happy to be right with us in a foreign house. The Boy lugged in some boxes belonging to his father, as he believed our house to be a place of safety.

One day I was in the city, walking along Nanking Road a few blocks from the Bund. Usually the street is crowded with vehicles and pedestrians. Suddenly I noticed that the street was empty. At the same moment a lady spoke from the recess of a shop entrance and asked where I was going. "Why, I'm on my way to the silk shop," I said. "You had better wait awhile," was her response. "A bomb was just thrown from the roof of a building in the next block." It was surprising how quickly I found myself inside that shop with a crowd of other passers-by.

Bob's idea was that if there was any trouble, I would be found close by. He said he always missed such things, but I reminded him of the bullet affair in Chungking. Each one usually has a share of danger, known or unknown.

45

Tense Times

(1927)

The interplay of politics, ambition, and envy, together with a desire to see the discredit of the new Nationalist leader, Chiang Kai-shek—all these elements fused to produce the Nanking Incident of March 24, 1927, in which several foreigners were killed by Southern troops.[1] Two days later I was at a meeting of the YWCA National Committee. I shall never forget the dismay and concern shown by its Chinese members. We were all faced with most alarming news as to the temper and actions of the soldiery there in Nanking. The Chinese were anxious to know the foreign attitude to the new National Government and wondered if we would be leaving China.[2] Our discussion settled nothing, but it showed us the sadness of our Chinese friends over the situation.

The Nanking Incident set off alarms around the world, but especially in Shanghai. If this attack on foreigners by Chinese troops was a forerunner of things to come, the situation could be very grave. The concern of our Chinese friends that we might be leaving China did not, at the time, seem so far-fetched.

In Shanghai the foreign military forces enforced a strict curfew.[3] Barbed-wire barricades were set up at key points. There were constant military patrols throughout the International Settlement and the French Concession. The city was divided into sectors. The national group in each area had in-

[1] Not much is known for certain about the background and motivation of the "Nanking Incident." Grace was accepting the later Kuomintang explanation—that the attack was Communist-inspired, intended to provoke trouble with the foreign Powers and embarrass Chiang Kai-shek.

[2] The "new National Government" was not the Left Wing "National Government" already in business in Wuhan, but the Right Wing "National Government" just then being established in Nanking by Chiang Kai-shek. The Wuhan government collapsed a few months later.

[3] Besides the naval forces normally in the area, all the principal Powers had sent military units to defend Shanghai. The American unit was the Fourth Marine Regiment. There was also the Shanghai Volunteer Corps, a sort of home guard organized by nationality. Finally, there was a very sizable police force. In the International Settlement the police had British officers and a large contingent of Sikhs.

structions for emergencies. Bob was responsible for notifying a list of Americans in our neighborhood. We kept a couple of small trunks packed, and suitcases stood ready in the upper hall. Many organizations, including the American Women's Club, opened relief headquarters. The American Community Church housed fifty people, members of the Augustana Synod Mission. These people were mostly of Scandinavian stock from Nebraska; they had been living in Honan and had suffered much hardship and loss. The gymnasium of the Navy YMCA became a women's dormitory with rows of cots; men had rooms on the upper floors; and the restaurant did a tremendous business.

Early in April I was in the North Hongkew section to pick up my supply of matzoth, the Jewish unleavened bread (I lived on a salt-free diet from 1925 to 1929 and ate no regular bread). While I was there a big sign was erected at the street corner by the Jewish shop I was in: "No traffic permitted north of this point." In the YWCA we were thankful that our Foreign Finance Committee had not renewed leases on houses occupied by our people on North Szechwan Road Extended. All but one or two of our secretaries had already moved south of Range Road.[4]

Bob and I were having tea one day at the Astor House Hotel. There was a sudden excitement at the Soviet consulate building, just across the street, as members of the Shanghai Volunteer Corps surrounded the building. This was a few days after the Chinese Government had raided the Soviet embassy in Peking. We heard that the Red officials burned masses of papers before clearing out. It was said that a thousand foreigners left Shanghai in one week, and all that spring outgoing ships were crowded. The tension seemed greater during the second week of April than during the first. After that, things gradually became less tense.

A friend with an invalid husband decided to take him to America. She offered us her large and attractive house. The move would save rent for the YMCA, and it was a better house for hot weather than the one we had been living in. We accepted the offer. Several days before we planned to move, the National Committee received a telegram from the Hankow Y asking specifically for Bob to go there. We did not know just what the emergency was, but Bob felt obliged to go. I was terribly upset, but a couple of house guests from Szechwan promised to help me through the move. When Bob's ship for Hankow entered the Yangtze it had to wait for a naval escort; just when we needed his help in the moving, he was sitting idle on shipboard only a few

[4] The area on North Szechwan Road Extended that Grace refers to is precisely the sector, beyond the boundary of the International Settlement, that Bob and Grace found to be of dubious safety in 1905 (chapter 3 and its note 2). Grace was the head of the committee making the decision.

miles away. It took him over six days to reach Hankow—the normal time was three. Bob returned home in late May, but went back and spent most of that summer in Hankow while the American secretary from that city, who was not well, took a holiday with his family in our new Shanghai house.

At a meeting of the American Women's Club in May there was a heated discussion about the suggestion of some of our members that we cable a conference in the United States of the General Federation of Women's Clubs to ask for its aid in securing protection for American women in China. I took part for the first time in club debate when I opposed this suggestion from the floor of the meeting.

In mid-June the lads and I went to Tsingtao. The big excitement of the summer for us was the building of a sailboat, centerboard and all, by young Bob, then sixteen. He had sent to America for patterns and had been working for some time in Shanghai on the small pieces. At Iltis Huk we had a two-story house with a large open veranda on the second floor. This was given over to the carpentry. Young Bob bought American lumber from the Dollar Company and was soon deep in construction work. By strenuous efforts he completed Flying Cloud just before we left at the end of the season.

The Chinese military forces in Tsingtao went into a state of extreme alert in early July.[5] Things were very tense for a couple of days: lots of soldiers around, machine guns at main intersections, and plenty of talk and rumors. After several days I was almost without money, and we had almost no food save potatoes. Rickshas were unavailable. Any pullers not already impressed by the military were in hiding. I was glad to get a ride into the city with some friends.[6] I carried a small American flag with me.

After a trip to the Y, where I secured money, and a purchasing time at the market, I went to the garage to hire a car. Cars, it seemed, had either been taken by the military or put into hiding. If I could supply a flag and would wait some time, a conveyance might be found. At last, I was off in a large open car with the top put back in the favorite beach fashion. There I sat all alone, surrounded by my purchases; a fish, two chickens, and the usual greens and fruits added color to the picture. I told the driver where we lived, and sat back in peace. When he took me into strange territory, I found that he was a stranger and had never heard of Iltis Huk. I was able to direct him and we got home safely, but much delayed.

That summer I went to the Tsingtao Barber Shop and Beauty Parlor where

[5] After Chiang Kai-shek took Nanking and Shanghai in the spring of 1927, the Northern warlords joined together to oppose Chiang's expected northward advance. The Northern forces actually drove south to the Yangtze in August. Tsingtao was experiencing ripples of this activity.

[6] Grace had no car in Tsingtao because there was no way of transporting the car that she had in Shanghai. In Shanghai, her car—with a chauffeur—was indispensable. Without it she could never have kept up the pace of her social, organizational, and club activities. Not many women in the missionary community had this mobility.

André, with a few snips of his long shears, cut off my long hair.[7] The coil looked very pathetic and made me think of our queueless friends in Chengtu in 1911. I was so distraught that I left my extra-good hairpins on his table, and went home with my new short locks blowing in the stiff sea breeze. It had taken me a long time to come to the point of the shears. My men had opposed it; but as soon as they saw me, they approved. So did I, and since then I have never even considered long hair. There is a vast relief in the absence of pins and fussing; and with "Irish hair" like mine, I do not need permanents, combs, or pins to give me the freedom and effect that suits my taste.

One evening soon after Bob's arrival in late August, Dick was absent when supper was ready. I supposed he was at a neighbor's, so after a wait we started dinner. Suddenly, the Boy came in to say that Dick's clothes were on his bed. He must be in the ocean. It was then fully dark. Dick was thirteen, thin and slender. Bob told me not to leave the house. He rushed off with flashlights to the beach, young Bob and his friend spending the summer with us going along. Our Canadian guest, a young woman from Peking, hurried around to the neighbors making inquiries. I spent some of the longest minutes of my life before I heard the welcome call from Bob. They had found the young chap watching some fishermen hauling in their nets on the beach. He had not realized how late it had grown.

Back in Shanghai in September things had settled down to more peaceful ways. There was the same old rush carrying us along in its usual way. The annual dinner of the American Women's Club was at the Hotel Majestic, and I was seated by Admiral Bristol.[8] It was a big thrill for me to respond to one of the toasts. I had occasion to remember it because Madame H. H. Kung thanked me for the toast when we met at the wedding of her sister, Mei-ling Soong, to General Chiang Kai-shek.

The Chiang-Soong wedding was in the same Hotel Majestic ballroom and was an interesting ceremony. What we saw in the hotel was the public ceremony; the religious one had already been performed privately at the home of the bride's mother. At the Majestic there were between eight hundred and a thousand guests. The flowers and decorations were lavish. The bright lights were intensified by reflectors to facilitate the movie cameras. The refreshments were varied and delicious. But the changing, beautiful scene in that incomparable Majestic ballroom will always be mingled in my memory with a friend's urgency to have some sausage rolls like those being passed at a

[7] André was certainly a White Russian. Thousands of these refugees from the Russian Revolution managed to cross Siberia and find a rather desperate haven in Manchuria and along the China coast. Generally speaking, they had to compete with Chinese for a livelihood. Hair-dressing and beauty care was one occupation in which they did very well. Dressmaking was another. Grace thought very highly of Lily, her Russian dressmaker in Shanghai.

[8] Admiral Mark Bristol was commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet (of which the Yangtze Patrol was a unit).

nearby table. We were close to the bride and saw her dress and veil. Each of us had a slice of the wedding cake. The whole event was a kaleidoscope of beauty, color, and light. I took my piece of wedding cake home and divided it so that each person in the household might have a taste, including the servants—who were much pleased. The newly-weds set up an establishment in a house two doors from us, and we often saw their dark blue Packard in our neighborhood.[9]

There was still some risk in travel, but Bob left again for Szechwan in mid-October. We heard from him at Hankow and at Ichang, and then there was a silence. Finally, on November 11, I received some letters that had been posted at Wanhsien. This was a relief because it meant that he had passed that portion of the river where there was most danger, both from the river itself and the troops and bandits ashore. He wrote that the steamer had been guarded by two hundred soldiers at the first night's anchorage above Ichang. In spite of this, some bandits got aboard and demanded $1,000 but were finally bought off for $100. It would seem that bandits and guards may not have been complete strangers. The ship was fired on several times, but they got through safely. And Bob was glad that no woman had been along.

The Hankow Y wanted Bob to be posted there permanently, but it was decided that we should remain in Shanghai. Bob was willing to go wherever he might be sent, though he still felt that his greatest contribution could be made through his knowledge of and friendships in Szechwan and his ability to provide a link between the two Szechwan Associations and the National Committee.[10] That was his main objective. Neither Association wanted to give him up, and in both cities he was in urgent demand for all their money-raising campaigns. The mails were very irregular that winter. Though Bob and I wrote constantly, there were often long gaps between mails. This made things harder for us, as there was still considerable anxiety in the air.

[9] Despite the Kuomintang support of the campaign against foreign settlements and the unequal treaties, the Chiangs were not the only high officials who saw no anomaly in their choosing to reside in the French Concession at Shanghai. Nanking, the capital, was about two hundred miles away.

[10] As a membership organization with varied and innovative activities, the YMCA relied heavily on regular conferences involving Chinese and foreign staff drawn from both the central, coordinating organization (the National Committee) and the local Associations. The motives were to "recharge batteries," introduce new programs, exchange experience, and enable the center to identify and assist in meeting local needs. The long travel time from Shanghai (as Grace has pointed out) deprived the Szechwan YMCAs of the benefit of these conferences, and meant that the National Committee (rather conspicuously) often lacked understanding of the situation and needs of the Szechwan Associations. Bob's assignment as regional secretary was an attempt to remedy this situation: since they could not come to Shanghai, he would go there on a regular basis as a representative of the National Committee. It seemed to work out that he made two extended trips a year (in the spring and fall), which involved his being away from Shanghai about seven months of the year. The suggested move to Hankow might seem to make sense, since it would put him six hundred miles closer to Szechwan; but, by removing him from direct contact for several months each year with the National Committee in Shanghai, it would reduce his ability to provide the linkage that was the purpose of his regional assignment.

46

Committee Woman

(1928-29)

It was a quiet holiday season at the end of 1927. Bob did not get home until mid-January 1928, and he left again three weeks later for Hankow, where he stayed until May.

I worked very hard that spring in the YWCA financial campaign. A friend and I made scores of calls and we were fairly successful. We met a number of rebuffs, a little rudeness, and once in awhile genuine opposition. It was often tiresome waiting to see the higher-ups in company offices, and we sometimes had to repeat our calls several times before seeing the person we sought.[1] One such series of calls was repaid by the most courteous treatment and fifty dollars in crisp, new bills—a great encouragement to us. As the YWCA at this time operated the only employment agency in Shanghai for stenographers, we did not feel that we had to offer any apology for asking businessmen to help this kind of essential welfare work.

Our worst experience that year was with a real dyed-in-the-wool Fundamentalist. Previously, she had been much interested in the YWCA, but now she told us that she was no longer interested. She would not give a cent, because during Lent we had had some talks at the YW by a faculty member of the Shanghai Baptist College. This man was a fine, forceful speaker, a person of breadth and vision. But to her, "his doctrine was broad enough to take in the very Devil." She kept saying this and that about the YW's "objectionable doctrine," so I took her up on that. My friend and I both insisted that the Christian Associations [YMCA and YWCA] taught no doctrine ; all such teaching was left to the churches. We tried only to put on a program of Christian helpfulness in which men and women of all denominations could

[1] Grace's companion on the fund-raising rounds was Gerry Fitch, whose husband, George, was in the YMCA. H. H. Kung was easier to see, but gave them only twenty dollars. T. V. Soong was hard to see, but gave them fifty dollars.

meet, drawn together by the love of Christ and a desire to further a Christian order of life. She became very fussed and finally declared emphatically that it was better for the Chinese—or anyone—to die in entire ignorance of the gospel than for them to listen to the preaching of a man like our Baptist.

There is nothing in the world that tells one more about human nature than fund-raising. I had my initiation during the Great War, and my education has continued with every such task that I have undertaken since then. One man—I omit his emphatic phrases—said to me: "Don't come to me for money for women! They are after me the whole time for it. My mother wants me to help her; my sisters have the same idea. My wife spends more every year; my daughters are already large enough to come to me for money. I don't get any peace at all; women are after me every day asking for money, money, money. I don't care how people and causes get their support, but I know I have my hands full with my own women and I cannot help any others by so much as a cent." Poor man, I felt great sympathy for him.

A visitor that spring was a woman who made herself out to be a friend of my sister-in-law in the Near East.[2] I had never met her before, and later discovered that she had used my name to my sister-in-law, who entertained her because she thought the woman was my friend. She was a person who wanted only the best; when I took her shopping, she looked through linens worth about eight hundred dollars and finally spent about eight. Her clothes were rather gay, with flying ribbons and furbelows. When I appeared ready for church on Sunday morning, she let out a great laugh and thought me very amusing. I hope I can see a joke, but I was rather at a loss to understand her levity until she said, "Well, I never! Do you know you look just like San Francisco in your tailored suit, your smart shoes, and plain hat." This was a true compliment. Few have pleased me as much.

The boys were very busy in school. Young Bob was the student manager and enjoyed the position, which carried some responsibility. We all looked forward to the summer: Tsingtao, the boat, and the outboard motor. Bob had promised that if the boat was finished and was a good job, he would buy an outboard motor for it. We had this in Tsingtao in 1928 and the lads greatly enjoyed it. Young Bob also made surfboards, so this was added to other vacation sports.

That spring, after a great deal of discussion, we had bought a residence lot in the French Concession, hoping to build there within the year. We were working on house plans and were getting help from Ferry Shaffer, our Hungarian architect friend. During the summer we learned that the International Committee did not approve of our building a residence. This was a great

[2] The sister-in-law was Bob's sister, Lulu Goodsell, in Turkey.

disappointment to all of us, and especially to Bob, whose dream of building had grown through the years. We were willing to promise that we would move from Shanghai if the need should arise, but that did not suffice.[3] Other Y men had built homes in China, and at first Bob thought he would build, whether or no. But we finally laid the plans aside. Bob told me that he had given himself entirely to the Y; he had never consciously gone against the desires of the International Committee; and he felt it best not to do so in this case.

The upshot was that Bob abandoned a cherished plan, sold the property, invested his money in other ways—and lost it in Shanghai's financial crash in the spring of 1935. Then, when his money was gone, he regretted bitterly that he had not built as he wished. We would at least have had the house.[4]

That autumn Bob was off on a strenuous trip into Shansi. He traveled by private car from Taiyuan to Sian and saw a lot of country new to him.[5] He reached home in Shanghai just before Christmas. The year 1928 had held both joy and disappointment for us.

For the past year I had been one of the representatives of the American

[3] The rationale for the YMCA rule was that owning real estate in the foreign city of one's assignment might limit one's transferability in case that was desired. The American Foreign Service has a similar but broader rule.

[4] One rigid taboo in our family was that finances were never discussed in front of the children. There is much in this sector that we sons have never known. Many years later, Grace told me that Bob had never received more than US$3,000 a year from the YMCA. But we had a bit more to spend than many of our missionary friends (examples: the motor car, my trip to Europe, and some of the mountain equipment Bob bought), so it was no secret that Bob had some outside income. This may have started earlier, but after Bob's father died in 1920, the ranch lands were divided and Bob received his share (one-eighth).

Besides improving our comfort, Bob used this income for good works: some extra-budget items for the local Y, school aid, help to Chinese friends in difficulty, and so on. He also started a commitment which, I am sure, grew in size and duration far beyond Bob's anticipation. When we left Chengtu in 1921, our cook, Liu Pei-yun, who had been our trusted and devoted servant since 1908, decided that he wanted to better himself by going into business. The Chengtu YMCA was about to start construction of a new building; the West China Union University was expanding and new buildings were being built; the city of Chengtu was growing and modernizing; there seemed, therefore, to be a good market for lumber. Nearby supplies were inadequate, but there were forests up the Min River in the "Tribes Country," which we had visited in the summer of 1921 and where Bob's friend Yao Bao-san was already cutting trees. Liu decided to go into the lumber business, and Bob—we assume—agreed to provide some funds to help him get started. Perhaps several things were in Bob's mind. He would be helping a deserving and capable man. He would be helping the YMCA and Union University in construction costs by ensuring that Liu gave them preferential prices. He would maintain contact with this area, which fascinated him, and develop a source of Tibetan religious and household articles (which he collected enthusiastically as long as he lived). And, finally, he would certainly recoup his investment and probably gain a generous profit. Alas, for reasons I did not know and Grace—if she knew—never divulged, things did not go as Bob expected. Instead of receiving a profit, he had to put more and more money into the enterprise.

Grace also mentions losses in the Shanghai financial crash of 1935. Those will best be discussed at that point in Grace's story.

[5] This trip to the YMCAs in China's Northwest would seem to indicate that his regional work in Szechwan had been considered useful.

Association of University Women on the Joint Committee of Women's Organizations. At the Joint Committee election at the end of 1928, I was chosen to be its chairman for the coming year.[6] This position took up a great deal of my time throughout 1929. I found the responsibilities engrossing, and I deeply appreciated a growing acquaintance with outstanding women of other nationalities. Like every other group, the organization had its problems; but we tried to stick to our goal of exerting an influence for the welfare of the city.

When I was approached about taking this chairmanship, I told the nominating committee that they should consider any possible implications of my belonging to the "missionary group." If it would be a hindrance to the organization, I did not want to accept. To many people in Asian port cities the word "missionary" is like a red rag to a bull. On river steamers I have had women sit at the same table and refuse to converse with me simply because I was classed as a missionary: nationality, education, family, or general appearance are nothing to these critics. I always had the effrontery to think I was about on a level with many that I met; sometimes I felt I might be able to classify people as well as did those who blithely consigned missionaries to the outer limbo of existence. The Joint Committee did not consider my affiliations a hindrance.

I was still a member of the YWCA National Committee and had my own special YW committee, the Foreign Reference Committee. This carried some of the responsibilities of what had been the Foreign Finance Committee. As each month rolled around, I found that I had many committees and such engagements to take up my time.[7]

My parents had not been well, and I wanted to see Jack, who was finishing his sophomore year at Oberlin. I decided, in April, that I would go to America for the summer. My trip was financed by Bob, and the Y had nothing to do with it. Young Bob finished high school in early June. We sailed a few days after his Commencement, on a ship which carried many of our friends. Young Bob visited California relatives and entered the University of Califor-

[6] I suppose it can be said that Grace, as chairman of the Joint Committee of Women's Organizations, had become the top club woman of Shanghai's large and diverse foreign community (although there was one Chinese organization—the Shanghai Women's Club—that was a member of the Joint Committee). It was just over three years since Grace had returned from America in 1925 and begun to be active. Not bad, one might say, for a woman whose health was deemed to be so frail that the doctors in America did not want her to return to China at all.

[7] Grace omits a great deal. In addition to leadership roles in the Joint Committee and the National Committee of the YWCA, she was active in the American Association of University Women, the American Women's Club, the Daughters of the American Revolution, and a Pan-Pacific Tiffin Club. She also was writing book reviews (usually at least one a week) for the China Weekly Review , published by her friend John B. Powell. And because the Yards in America were having a difficult time, she was buying quantities of Chinese needlework goods for Mabelle to sell. Grace's diaries indicate that she usually tried to sleep late in the morning; but she was normally up before tiffin, and then it was all "go," often until after midnight.

33

Grace in her active Shanghai days—probably during her year (1929)

as chairman of the Joint Committee of Women's Organizations.

nia at Berkeley that August. I visited my parents in Southern California and relatives in several states.

Jack was working at a boys' camp in Michigan. As soon as his season ended, he met me in Chicago. I got off my train from the west early one morning and found him waiting, having reached the city a couple of hours ahead of me. I had not seen my oldest son for more than two and a half years, and was proud of the tall, lithe, sunburned young chap who replaced the

stripling of seventeen that I had parted with in Shanghai.[8] He went with me on several visits, and I had a week with him in Oberlin where I saw his surroundings and met his friends.

Then back to California I hurried. After farewells there—it was very hard to leave young Bob behind—I was off by train to catch my ship in Vancouver. In the sleeper I had some conversation with a lady who seemed familiar. Later, we met again on shipboard and I learned that she was Dr. Aurelia Rhinehart, the president of Mills College, whom I had met years before when I was a student at Berkeley.

An especially interesting group of my fellow passengers was en route to Japan to attend a conference of the Institute of Pacific Relations. However, sad for me, they were all in first class, and I was in second (this gave me more to use for gifts to take back with me). The rules governing contacts between classes were being rigidly applied. A friend invited me to dine in first class; I had gotten out my evening clothes and was about to dress when he came to my cabin to tell me, in embarrassment, that he was not allowed to entertain me. I then attempted to entertain him and a few others: such a thing, the steward assured me, could not be.

I did have a number of old friends in second class, and I made at least one new one—a young Japanese woman returning from school in England. She had been in another cabin, but her cabin-mate made some fuss about the assignment. I told the steward I had no objection to having her with me. She was a quiet, pleasant roommate.

In our social hall, I played cards almost every evening with three English missionaries, ladies traveling alone like myself. There were several Fundamentalist ladies aboard and they looked askance at us. One of them asked me one day if I was saved. After her opening, we went on to have many conversations. I found I had spent many more years in China than she, and that I knew far more of Chinese life and problems. She had no interest in the YM or YW; most Shanghai church work she considered futile; and of welfare organizations she wanted no part. All that mattered to her was "the evangel" as interpreted by her rigidly narrow sectarianism.

I could not find that she read anything. I was finishing a re-reading of The Brothers Karamazov , and had Clive Bell's Civilization . She would have none of them and even refused Man's Social Destiny by Ellwood. A travel-wise New York friend had sent a large parcel of current magazines to the ship, with the instructions that it was to be delivered to me on the fifth day out. I pressed some of these on the Fundamentalist, but she was not interested. Despite her

[8] Also waiting on the platform to meet Grace was Mabelle. They had not seen each other for more than five years. Indeed, to meet and stay with the Yards was the reason we met in Chicago: Jim had become university chaplain at Northwestern University in Evanston.

concern for my salvation, she was not interested half as much in me as I was interested in her!

Back in Shanghai, I threw all my energies, renewed by the sea voyage, into the affairs of the Joint Committee. For some years there had been talk of staging a large international pageant. The expense, lack of a trained director, and other difficulties loomed large. Now, the China National Committee of the YWCA underwrote the production, and the National Board of the YWCA in America loaned us a director of skill and experience. The Joint Committee undertook the work. Numerous committees were busy for weeks. And the last days were full of errands, rehearsals, unexpected emergencies, sudden changes, and the thousand and one details that go into the staging of such a production.

There is a famous phrase in the Confucian classics: "Within the four seas, all men are brothers." We named our pageant "Within the Four Seas." We advertised and advertised. There was a gorgeous poster, but it offended our White Russian friends because, in drawing the national flags, the artist had included the emblem of Soviet Russia. There were three performances. At the first, the hall was not full. Attendance was better at the second. And for the matinee on the third day, we had a packed house. The effect was cumulative; if we could have had one or two more performances, we would surely have had big crowds—and ended up with a profit.

Our director told us that it was to be expected that we would not at once reap the full benefit of our efforts, that they would appear as time passed. Certainly we benefited by learning to work together. Never can those dancing, lively groups of Scandinavians, Hungarians, Russians, and many others in colorful costumes fade entirely from our minds. At the end, when our tots from all countries in their varied national garb mingled joyfully on the stage with a message of Peace and Brotherhood, we did catch a glimpse of idealism that at the time seemed almost tangible. The Japanese children were so darling. Perhaps if we had a world ruled by children there really would be an end of war!

But all this was work. I look back on that week as the most hectic of my career as housekeeper, helpmeet, and committee woman. Immediately after the last pageant performance, Bob started west again. Meanwhile, I welcomed old Y friends, Will and Mary Lockwood, who were to spend a couple of months with Dick and me.[9]

[9] The Lockwoods, it may be recalled, welcomed Bob and Grace to China in 1905; and it was with Mary that Grace shared a shaking bed on her first night in China (chapter 3).

47

Storm Brewing

(1930-31)

With Bob away, the family gathering for Christmas that year was reduced to Dick and me. In Szechwan, Bob had an infected hand. Typically, I heard about it, not from Bob, but from a friend in. Shanghai who had received a letter from a friend in Chengtu. When I learned the identity of the Chengtu friend, I stopped worrying. He was famous as an inveterate purveyor of bad news. Time proved that I was right, and Bob came home safely soon after the new year of 1930 had begun.