6

The Avándaro Rock Festival

In September 1971, just three months after the deadly paramilitarist attack by the halcones on protesters in Mexico City and nearly three years to the day after the government-orchestrated massacre of students and workers at Tlatelolco, Mexico became the first Latin American country to present its own rock-music festival, popularly known as Avándaro. The concert drew more than 200,000 participants from across the country, and it clearly marked the commercial apex of La Onda Chicana.[1] But if the cultural industries hoped to emulate the marketing success of Woodstock, a societal backlash in the aftermath of Avándaro all but halted continued exploitation of the Mexican rock market. Attacks came from the left and the right as blame was assessed for the "lost souls" of Mexican youth. The Echeverría regime used this backlash as the basis for a frontal attack on La Onda Chicana. The regime's discourse of Third World nationalism was expanded to include public support for a Latin American counterpart to rock: the nueva canción (New Song) and folk-protest movement associated especially with left-wing regimes in Cuba, Chile, Peru, and now Mexico. Even though the cultural industries' support quickly withered, Mexican rock did not disappear. Native rock retreated to the hoyos fonquis, where it was fully reclaimed by the lower classes. At the same time, foreign rock retained its status as vanguard culture and coexisted with the new Latin American song movement, despite overt ideological battles waged in more radical corners against all manifestations of yanqui cultural designs.

Valle De Bravo, Avándaro

The concept of holding a rock festival as a showcase for native talent emerged as a logical consequence of the probing for commercial opportunities of La

Onda Chicana. At the same time, like Woodstock, there was little notion beforehand that the festival would take on the proportions it did. In fact, the concert itself—promoted as a "festival de rock y ruedas" (festival of rock and wheels)—was originally scheduled as only a sideshow to an annual road derby held each year at the Valle de Bravo, Avándaro, site, about two hours' drive northwest of Mexico City. Still, unlike the tocadas, this concert involved the participation of powerful commercial and political interests. Initiated by Justino Compean of the advertising firm McCann-Erickson Stampton, which managed the Coca-Cola account in Mexico, Avándaro offered a high-profile promotion of native bands and thus represented a key moment in the commercialization of the Mexican counter culture.[2] As one person involved in organizing the festival put it, "We've definitely looked to not bring in foreign bands, because we're trying to promote Mexicans in every sense.... Specifically speaking, well the British have very popular bands, as do the Americans, the Germans, the whole world, and very few Mexican [bands] have attained success. So we believe that by promoting this kind of festival, any number of Mexican bands can become an international hit. Certainly many of them deserve it, no?"[3]

Clearly the commercial success of the Woodstock festival demonstrated a potential for records and films.[4] Herbe Pompeyo, former artistic director with Polydor Records (now Polygram), revealed that Polydor hoped Avándaro would generate a "great popular explosion [of native rock] ... with all the accompanying paraphernalia [of the rock counterculture] that already existed in the United States."[5] The festival was even carried live over Radio Juventud, a Mexico City station, until transmission was abruptly cut off by government censors because of foul language. This occurred when the band Peace and Love shouted: " ¡Chinga su madre quien no canta!" (Screw your mother, whoever doesn't sing!) in response to lines from the Chicano song, "Marihuana boogie."[6] The television giant Telesistema was also there in force, preparing for television possibilities.[7] Meanwhile CBS, anticipating record spin-offs to follow, hired a helicopter to circle the concert grounds and drop leaflets announcing: "La Ofensiva Pop 71 de CBS está presente en Avándaro con Los Tequila," one of the featured groups.[8] In the center of the town hung a welcome banner: "Paz y amor. Coca-Cola."[9] .

Still, in scheduling the festival as a side-show to a road derby rather than as the central attraction (as in the case of Woodstock), the organizers seemed to be probing the commercial potential of native rock rather than cashing in on it explicitly. This fact was reflected in the extremely poor sound system and inadequate organization that characterized the festival

from start to finish. It was also reflected in the paltry sums paid to the bands, which received 3,000 pesos each, around U.S. $250.[10] As news of the festival spread, moreover, any practical notion of creating a controlled rock environment, suitable for commercial purposes or otherwise, quickly vanished.

The immediate danger from the organizers' perspective, as well as from that of the Echeverría regime, was that such a mass gathering of youth would turn into a political rally, in itself a clear misreading of the movement's tactics and goals.[11] For rock represented a turning away from traditional political organizing. The ideology of rock as it was practiced in Mexico was captured more by the concept of desmadre and the re-creation of community out of chaos than by a notion of struggle embodied in a socialist-inspired discourse of "unity through discipline." Avándaro, commented the writer Parménides García Saldaña afterward, was "a demonstration without speeches, or leaders, which showed that the only thing we want is music and marijuana."[12] Fearing that student organizers might be present among the crowd, precautions were taken nonetheless: "There are students present, and some will want to take control of the microphones in order to make a statement; this will not be permitted. Access to the microphones is under watch by four armed guards. It is necessary to identify yourself in order to pass [onto the stage]. The army is nearby. The presence of uniformed police and agents is a show of support [for the concert]."[13] With the exception of a "religious survey" passed out by the newspaper Novedades , the distribution of all literature was prohibited.[14] Federal, state, and local armed forces made the government's presence ominously apparent: up to 1,000 soldiers with machine guns milled around the perimeter of the concert grounds, though no violent incidents were reported.[15]

As it turned out, at least two efforts linking rock to politics did occur. The first was an announcement of a "minute of silence for 'those who died,' " which initially appeared to some in the audience as a political reference. "I thought that it was for what happened at Tlatelolco or [the halcones attack] of June 10th," commented one participant. "But it was for Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, and Jimmy [sic ] Hendrix."[16] The second, this time more direct, came in a song dedication by Alejandro Lora of Three Souls in My Mind: "In this festival a lot has been said about peace and love, and those things are really cool, but that is not rock. To show that we're concerned about things such as the tenth of June we're going to play a song by the [Rolling] Stones called, 'Street Fighting Man.' "[17] In the end, tens of thousands of youth, mostly from Mexico City but also making pilgrimages from all parts

of the country, descended on the Valle de Bravo site for a long, cold, and wet night of music and revelry.

The festival itself officially began at 12 noon on Saturday, 11 September, with a yoga session, though large numbers of youth had begun to arrive several days earlier. While a number of lesser-known bands warmed up, the first scheduled act, Los Dug Dugs, did not begin until around 10:00 P.M. on Saturday. The music continued until 8: 00 A.M. Sunday, when the last band to perform, Three Souls in My Mind, "had to end only a half-hour after they started: the sound system conked out altogether, and there was little option but to declare the festival over at that point."[18] In the aftermath of the concert, the road derby would be canceled. So too were plans for any future commercial exploitation of native rock. Orphaned by the mass cultural structure that had at various times sought to contain and then to cultivate it, Mexican rock—and the cultural memory integral to La Onda Chicana—would all but disappear from the national landscape.

The Participants

At Avándaro, the increasingly diverse class makeup of La Onda showed its forces. Above all, it was the striking presence of so many lower-class youth, the nacos, as they were derogatorily called by the middle and upper classes, sharing a common space and musical culture with other youth that caught the attention of many writers. "Only a small minority is made up of the [upper-class] 'fresas,' " noted one writer. "The immense majority is formed by the [dark-skinned] 'raza.' It seems as if the entire youth population of Ciudad Netzahualcóyotl [a lumpen-class district] had descended on Avándaro."[19] The exact numbers of participants from each class are, of course, unclear. While some reports cited a majority working / lumpen-class element, the following is more likely an accurate description: "The majority ... belong to the middle class; they are sons of bureaucrats, small merchants, small industrialists, professionals.... There are two minority groups: the first are sons of specialized workers, inhabitants of the proletarian colonias [neighborhoods] of the Federal District.... The second are the sons of financiers, industrialists, and [government] functionaries. They have arrived by car.... They are inhabitants of [the elite neighborhoods] Las Lomas, Polanco, San Angel, Florida, El Pedregal."[20]

In any event, it was clear that the class makeup of La Onda had diversified considerably since its pre-1968 origins. While at one level this cross-class alliance in support of a native rock movement was impressive, its real

depth was less certain. Upper-class youth could boast of their easy access to foreign rock; for them, native rock would never be more than second rate. Middle-class youth were more likely to long for the success of a native movement, but their cynicism toward the quality of the music and the "education" of the rock audience made their abandonment of support after Avándaro predictable; it was via the middle classes especially that foreign rock was sustained throughout the 1970s as "high" popular culture. For barrio youth, meanwhile, rock had worked its way into an integral aspect of everyday life, where live performance offered the possibility of self-representation in a society which mocked and marginalized them.

All reports also remarked on the dearth of women at the festival.[21] While this was not necessarily an accurate reflection of female participation in La Onda in general, it does remind us that Mexican women faced much greater restrictions on their mobility and freedom of expression than did men. For the women who did attend the Avándaro festival, their motives, in part, suggested the impact of a countercultural discourse that stressed notions of community and defiance toward patriarchal subservience. For example, one twenty-two-year-old woman who attended the festival—"I went because I get along well with my mom"—remarked: "I felt for the first time a total independence, the absence of property. All of Avándaro was the absence of property; in terms of belonging to people, nothing belonged to anyone, except for myself—I belonged to myself."[22] For Lila Orta, a recent marriage meant the opportunity to attend Avándaro: "If I hadn't been married, most likely my parents would never have let me go.... So for me, it was an important personal challenge. I told myself: 'I'm married, I don't live with my parents any longer.' "[23] While at one level the concert was a "personal challenge" made possible by the fact of her marriage, after further reflection she remembered her experiences at Avándaro in more nightmarish terms. For in reality she found herself bound to the wishes of her husband and his friends:

Well, when we went to Avándaro I had no desire to go. I had no idea what to expect. I knew that it was going to be in the countryside, [and] I said to myself, "What am I going to do in the open country if there are no houses, or bathrooms?" ... The fact was, I was afraid of something happening [since I was pregnant]—that I might slip and fall. I fell like three times, [and] I told myself, "From here, I'm headed right for the hospital, because something is going to happen [to the baby]." I went because they dragged me there. In reality, I didn't have much of a choice except to try to enjoy myself, because although I was annoyed,

angry, cursing right and left—they weren't going to bring me home, right? My husband said to me, "You're coming with me, because you're coming with me." And so, I didn't say anything. I just went. I wasn't very happy.[24]

Curiously, because nudism was a central feature of the counterculture philosophy—and due to the dearth of women generally—photographs and film footage of Avándaro show a large number of nude men: standing around, bathing in the river, even dancing. Yet a reminder of the double standard borne by women was the scandal created when a sixteen-year-old girl initiated a "strip-tease" on top of a lighting platform. Piedra Rodante , the Mexican version of Rolling Stone , published six photographs in sequence of the act, accompanied by the text: "Wow, that chick really caught the vibes!"[25] Meanwhile, the mainstream press focused on the exhibitionist act as a means of highlighting the degenerate moral state of Mexico's rock culture generally. Later investigated by the attorney general's office, the woman was diagnosed as "suffering a severe problem of adaptation occasioned by the absence of her parents, who live in Monterrey."[26]

Nonetheless, the ideology of rock stressed the myth of a renewed community, and it was this idea that transformed Avándaro, like Woodstock, into a symbol of La Onda's possibilities. In fact, while no deaths were directly linked to the concert (traffic accidents took several lives, however), desmadre clearly triumphed. Footage from the event shows tightly pressed crowds passing bodies through the air, and reviews mention the rowdiness of those present. In one incident a drummer was hit on the head with an empty bottle hurled from the audience. In the battle over space that rock spearheaded—the need to capture space, to reorganize its symbolic infrastructure, if only temporarily—Avándaro represented a "liberated zone," albeit a contradictory one and under the watchful guard of the soldiers present. As one participant described, "one talked about [Avándaro] as being a part of Mexico that was free. In 1968 the [UNAM] was also declared a liberated territory, and I think that Avándaro was a little like a parody of that: a place where you could do what you wanted."[27] It was in this liberated space that Mexicans from all classes took stock of their numbers, exchanged histories, encountered other histories similar and dissimilar to their own. A chance participant from the United States later described the mood in the days after the event: "I remember the next day or so wandering around Mexico City flashing the peace sign at others who were coated in mud—'Avan-daró' you said, like it was a secret signal that you had been there. Like it was something really important. Somehow, because of the mud, you could just tell who had been there [to the concert]."[28] A commemora-

tive volume of photographs called Nosotros (Us), published by Humberto Rubalcaba of the rock band Tinta Blanca, took pains to emphasize the magic and harmony of the event. "We went to see what we are like and how we act," reads a part of the text. "We went to get to know ourselves better, to know ourselves as being a part of the others, as well as [to support] the others.... [At Avándaro], [w]e mutually discovered that we exist."[29] Perhaps also, youth mutually discovered that profound differences divided the rock community along lines of class and gender.

Avándaro's Reimagining of Community

Virtually all of the music performed at Avándaro was in English. This reflected the trajectory of the Mexican rock movement at the time and captured the element of fusion that was central to La Onda Chicana. This fusion was also widely present in the importance attached to symbolic acts of reappropriation at the festival. Through a free association of symbols and signs of the nation—and of a universalized countercultural movement, generally—the youth culture actively sought to forge a new collective identity that rejected a static nationalism while inventing a new national consciousness on its own terms. As I have argued, this new consciousness was rooted in the notion of a Chicano identity: the fusion of a Mexican nationalist discourse with a countercultural discourse emanating from the United States and elsewhere. Such a shift in consciousness allowed for the simultaneous reembracement of national culture within the framework of an ideological distancing from an official nationalism linked to the state. The sense of participating in a global rock movement heralded by Avándaro thus offered the possibility of transcending nationalist ideology even as one reinvented it. As José Enrique Pérez Cruz, a participant, related, "I think, in a certain sense, we could say that [rock] fit the communist slogan, 'Workers of the world unite!' That is, 'Rockers of the world unite!'... Above all, [rock represented] a repudiation of borders. That was the real function of the music, for even when you didn't understand the lyrics, you still enjoyed the music. And that linked us [as Mexicans] to England, Spain, Latin America. Yes, that's the function I see in the music."[30] This separation of nation from state implied a threat to the legitimacy of the ruling party, which had always claimed for itself a privileged relationship to the national patrimony.

Perhaps most representative of this reappropriation at Avándaro was the transformation of the national flag. Reinventions of one's national flag and the discovery of new symbolic value through such reappropriation were

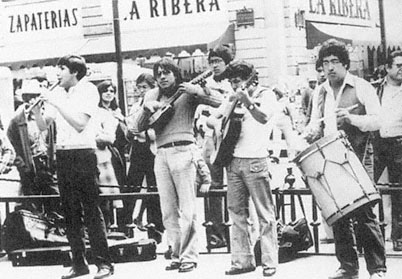

Figure 15.

The peace sign replaced the eagle and serpent emblem on numerous

Mexican flags at Avándaro, here seen being waved. Source: Film still, Concierto de

Avándaro (Dir. Candiani, 1971), Filmoteca de la UNAM. Used by permission.

common in countercultural movements worldwide. For example, incorporating the flag as an article of clothing became a statement of freedom from the state or the official meanings assigned to the flag (such as militarism in the United States). In Mexico, as in certain parts of the United States during this same time, strict laws prohibited defilement of the flag and other national symbols.[31] Yet the presence of flags—national and international—was pervasive at Avándaro.[32] This in itself was scandalous: the Mexican flag was hung from makeshift tents and wooden flagpoles against the backdrop of a mud-soaked multitude flouting national values. But photographs of a transfiguration of the national flag shocked not only conservatives but leftist intellectuals as well: several flags had replaced the eagle and serpent emblem with the peace sign (see Figure 15). Not only did this act represent a subversive affront to a primordial national icon, but, in that the ruling regime had long since identified the PRI with the colors and symbolism of the flag itself, the act suggested an attack on the political system as well. The peace symbol, referred both to the student movement of 1968 and to "peace

and love" (also the name of a Mexican band), also appeared by itself on several homemade banners at Avándaro.[33]

But if the regime and conservatives were shocked by the reappropriation of the Mexican flag, intellectuals were even more disturbed by the widespread presence of the U.S. flag at Avándaro. This symbolized for many on the left La Onda's apparent reverence for imperialist culture, epitomized by the use of English as a dominant rock idiom. For intellectuals and other leftist critics, many of whom had participated firsthand in the student movement of 1968, the prominence given to the U.S. flag at Avándaro reflected their worst fears of cultural imperialism. Whereas in 1968 the "core" hegemonic powers, especially the United States, had been the direct object of hostility and frustrated rage by youth, the rock counterculture seemed to have swung that influence in the opposite direction. What this leftist criticism failed to take into consideration, however, were the multiple uses of rock music and thus the alternative interpretations that embracing "imperialist culture" might have had. Thus, while the U.S. flag stood for imperialism at protests in 1968, at Avándaro in 1971 it symbolized solidarity with youth abroad and especially the Chicano fusion at the heart of the Mexican rock counterculture. At one point, a large U.S. flag was integrated into a frenzied group dance, where it was shaken and waved about (see Figure 16).[34]

The evident centrality of a foreign discourse and symbols to La Onda Chicana did not reflect a simplistic subservience by the movement to colonial values, or even necessarily to foreign capital. After all, local capitalist interests both large and small were also involved in rock's diffusion. Even the fact that much of the music was performed in English did not necessarily reflect a homogenization of global culture at the hands of transnational cultural industries emanating from the metropolises. The trend toward experimentation in Spanish was evident at the time, and, while a global marketing structure clearly gave preference to English-language material, it was inevitable that a market for Spanish-language rock would sooner or later appear. This optimism for the future direction of La Onda Chicana was expressed by Armando Molina of La Máquina del Sonido: "The musical revolution [known as] 'Rock Chicano' is in full ebullience; each day the quality improves and chances for success are enhanced. To date, all of the groups are creating and providing us with different sensations; the diverse [musical] tendencies are proliferating and making manifest their initial impact."[35] For those who attended the festival, Avándaro therefore represented the triumph of a Mexican rock culture, its insertion into a global

Figure 16.

During the Avándaro music festival the U.S. flag is held up and danced

around, symbolizing the cultural fusion at the heart of La Onda Chicana. Source:

Film still, Concierto de Avándaro (Dir. Candiani, 1971), Filmoteca de la UNAM.

Used by permission.

rock ecumene from which it was previously marginalized. Displaying symbols otherwise regarded as imperialist—that is, the U.S. and British flags—must be understood in the context of La Onda Chicana's pursuance of direct representation in the universal rock movement. "We've done it," came a voice from the platform. "We don't need gabacho [U.S.] or European groups. Now we have our own music." As one participant afterward wrote: "At Avándaro, a feeling of 'raza' was awakened. We understood that we are Mexicans, not gabachos. It's our counterculture [onda]."[36]

This is not to deny the impact that a foreign model had on the ideology of the festival. The legend of Woodstock, in fact, weighed heavily on the minds of many participants, even influencing their actions and gestures. This was reflected in the promotional material for Avándaro, which drew on imagery and language from Woodstock. "I know a place high up in the mountains where it rains, the sun shines, and there's music, beautiful music," reads one promotional announcement in apparent emulation of the Woodstock literature. There was also a Spanish translation of a statement made at Woodstock (and footnoted in a citation on the pamphlet): "The

person at your side is your brother. If you hurt him you're the one who bleeds."[37] And when the rains began at Avándaro, a rhythmic chorus reportedly rang out in English: "No rain, no rain," exactly mimicking the famous chant at Woodstock, which by this point had been commodified.[38] For the organizers of Avándaro the idea was nothing less than to "achieve the feat of bringing modern culture, already found throughout the world, here too."[39] Quoting a pamphlet handed out at the concert, the goal was "to experience the reality that we have wished for so much."[40]

While Avándaro represented the appropriation of a vanguard image of modernity borrowed from Woodstock and fused with local cultural practice, the ideology of the Woodstock festival itself likewise centered on the appropriation and romanticization of folkloric culture in part borrowed from Mexico, and from "authentic" cultural practices more generally. "We're setting an example for the world,' announced one performer from the stage at Woodstock.[41] It was in part an example of how rock (as "modern" culture) and folk (as "authentic" culture) were not only compatible but also interdependent. More fundamentally, it was an example of how rock was an organizer of community. And if Avándaro was heavily indebted to the model of Woodstock, the latter was also at least indirectly indebted to Mexico. Indeed, Santana's performance at Woodstock epitomized the material as well as symbolic impact of these transcultural exchange processes. His success launched the possibility that Mexican rock could establish itself within a world market, while the "Latin rock" sound and image he cultivated contributed to the practices of Third Worldism that were intrinsic to the ideology of the U.S. counterculture more generally. Woodstock and the entire U.S. countercultural movement, for that matter, depended on the usurpation and appropriation of a universalizing metaphor of indigenous authenticity that the proximity of Mexico to the United States in part provided. Other repertoires, such as Native American, Afro-American, Indian, and Asian, existed, of course. But Mexico, especially for those living in the Southwest, offered a close and tangible experience of an exoticized Other.[42]

Assessing Blame

The backlash against Avándaro was swift and had immediate repercussions on the entire rock movement. News and images related the event as harboring a community of drug addicts, nudists, and corrupters of national symbols. This struck at the moral conscience of conservatives, but it equally horrified those on the left. A consensus of culprits in fact emerged in which

the finger was pointed at compliant government officials, profit-hungry cultural industries, lax parenthood, and U.S. imperialism. Practically no one stood up for the festival in the days and weeks afterward. As Jueves de Excélsior editorialized:

It was the business deal of the century for drug dealers on the "Sabbath" at Avándaro that justifies society's great alarm. A mayor signs a permit authorizing a car race, and for one Mexican night (?) [sic: a reference to the organizers' original plans], a small village is converted by a businessman into a nudist camp and a refuge for drug addicts where, at the very least, marijuana, mushrooms from Oaxaca, LSD, and perhaps even opium and alcohol are consumed.... This, what happens every eight days in the United States, has unfortunately occurred for the first time now in Mexico.[43]

The newspaper Excélsior decried the "numerous violations, including the illegal use of the national flag, all of which are a consequence of the possessed imitation of patterns present in other societies."[44] This point was reiterated by the secretary of interior affairs, who stressed the "illicit use of the national flag, to the point of its deformation."[45] In the conservative provincial capital of Puebla, a group calling itself "New Youth" organized an anti-Avándaro rally. Protest leaflets declared: "In Mexico there is only one flag: the national one. In Mexico there is only one true youth: that which is patriotic. Youth have only one ideal to live up to: Mexico."[46] Seeking to stem fallout from the festival, the attorney general's office announced the launching of an investigation into the legality of the concert and a search for those "responsible."[47]

Indeed, the issue of responsibility dominated much of the sensationalist reportage of the festival. Under a series of color photographs displaying scenes from Avándaro, the news magazine Siempre headed one article: "Government, Church, Parents: We're All Responsible for This!"[48] One letter to the editor accused the government of "spoiling [youth] instead of giving them a good smack,"[49] which reflected the assumption that such an event could only have occurred with the PRI's blessing. There was truth to this, since Carlos Hank González, governor of the state of Mexico, had in fact signed the necessary permits for the festival; he later took much of the heat for its scandalous impact.[50] "The authorities of the state of Mexico have been very benevolent and farsighted," commented Alfonso López Negrete, a coorganizer. "They've given us everything: press permits and ample cooperation on the part of the army, as well as from those inside the government who are in charge of maintaining order."[51] Luis de Llano Jr., of Telesistema, who was in charge of filming the festival, attempted to de-

flect criticism of the media's role by pointing out that the Department of Tourism had helped promote the event (indirectly, one should add) by printing "a large number of wonderfully illustrated pamphlets ... inviting people to visit Avándaro," which continues to be known as a mountain resort for the elite.[52] The complicity of certain government officials, if not at the national level then certainly at a local one, was clear. But did this in fact indicate a sanctioning of the festival by the Echeverría regime for political reasons of its own? Or did it simply reflect the opportunism of local officials influenced by likely profits from the festival?

There was good reason to suspect that Echeverría knew in advance about the festival and had permitted it to go forward. Only with permission from high up, most observers reasoned, could an event of such magnitude have taken place. With the memory of 1968 and the more recent attack of 10 June on the minds of all youth, many in fact feared the possibility of a government setup at Avándaro. As one participant recalled, "In planning to go to the festival, I was quite dubious and suspicious. Many were saying that once we arrived there the army was going to be waiting for us, and sure enough they were waiting, though not to repress us but supposedly to guarantee order."[53] The army's pacific stance throughout the festival—for example, refusing to make arrests for drugs (many later attested that the army itself was actively distributing marijuana)[54] —signaled that orders had been given to desist from provocations. This foresight was also reflected in the guidelines of the official pamphlet distributed by organizers: "The presence of the military forces and police is to ensure that a specialized body exists that is available to assist in giving help to those who require it.... Those in uniform should be identified as one who gives his help as if he were a brother."[55] Furthermore, when it became evident that many of those in attendance were stranded for lack of return transportation, President Echeverría ordered 300 school buses sent. This announcement produced both cheers and chiflidos from the crowd; at any rate, it seems that only a smaller number actually arrived. But combined with the bizarre omnipresence of armed soldiers refusing to intervene, these actions seemed to confirm the belief by many that the central government had indeed authorized the festival as a way to monitor, if not explicitly coopt, the youth counterculture.[56]

The Leftist Critique

While the press and conservatives expressed outrage against the "satanic festival"[57] and the denigration of buenas costumbres by the counterculture

generally, voices from the left also used Avándaro as a pretext for condemning the rock movement. Conservatives and leftists coincided in their identification of the mass media as the leading culprit in the corruption of youth. One writer for Jueves de Excélsior , for instance, argued: "We know that the mass media invent false idols which are fed to youth at their expense."[58] An emergent polemic, moreover, viewed rock as imperialist not only because it originated in the metropolises but also because many intellectuals regarded rock music as antithetical to political organizing. Thus a recently released leader of the student movement denounced Avándaro as amounting to a government plot to anesthetize youth: "As long as we lose ourselves in this kind of gathering, the most reactionary forces, the government, will be happy. They promote and make [such gatherings] possible, looking to drown out the just and valid voices of rebellion and dissatisfaction among youth, hoping that with a few pesos spent on drugs, the repression of 1968, the massacre of Tlatelolco, the assassins of last June 10th, in sum all of the injustices committed against the people, will be erased."[59] As Carlos Monsiváis later summed it up: "The left [saw] in Avándaro a plot to depoliticize youth, a licentious step against the memory of June 10th. The right was terrorized by the violation of Hispanic tradition."[60] One could not imagine a clearer manifestation of cultural imperialism than the phenomenon of Mexican rock groups modeling themselves after their foreign counterparts and performing in English. "At Avándaro," concludes a commemorative book of photographs and text, "one saw between green smoke [an apparent reference to marijuana] a small but synthetic image of Mexican society in its absolute state of dependency."[61]

To be sure, this position was not unanimous. The writer José Emilio Pacheco, for example, argued in an editorial in Excélsior that "Woodstocktlán"—as he called the festival—allowed youth to express themselves freely, to be "liberated from tensions that are becoming more unbearable every day." "After Tlatelolco," he wrote, "every party became a funeral. Having fun has ceased to be spontaneous, [and has] unconsciously become an object of determination." Avándaro had offered youth "not only the possibility to hear music and avoid being beaten up by halcones and porras but also an opportunity to be in the open country ... knowing that for two days straight, el relajo [going wild] was an order and obligation" for all present.[62] The well-known television news reporter Jacobo Zabludovsky accurately argued in the introduction to Nosotros that Avándaro must be understood within the unfolding logic of repression in Mexico: "One cannot understand Avándaro without [considering the massacre of] 1968, without [considering the paramilitarist attack of] June 10th [1971]. One cannot

understand the youth of 1971 without [recognizing] the passion of those three years and without [understanding] the experience we [sic ] have gained."[63] The radical priest Enrique Marroquín, who was outspoken in his defense of La Onda, perhaps best articulated a nonimperialist interpretation of Avándaro: "One criticizes precisely those of us who are trying to re-conquer a genuine experience of our identity [raza], sure that 'rock will speak for our people.' We want to find our music, make it an expression of what we carry inside of ourselves; make it truly 'folklore,' this understood in its original form and not simply as an attraction for tourists. In this sense, the rock at Avándaro was a rebirth of our raza."[64] At a conference organized shortly afterward titled "Who Was at Avándaro?" held in the Israeli-Mexican Cultural Institute, the writer and critic Ricardo Garibay concluded:

Youth, those who were at Avándaro and those who weren't, are living Avándaro as if Avándaro were still occurring or had just ended. They are living it as something they themselves created without knowing with exact science how or why, or what for. They live it still—for how long will they live it?—as if something had stayed within a parenthesis, like a product of the atrocities that stayed between parenthesis, like the measure of a society without a foundation, without firm ground, from which they feel detached, apart, enemies, a society that doesn't consider them, and that they don't want to consider. Yes, they are like foreigners in their own nation, in their own land.[65]

Thus for most intellectuals, Avándaro quickly came to symbolize a vision of youth cut adrift from the system, or worse yet: colonized "foreigners in their own land," a phrase suggested by Carlos Monsiváis (writing from abroad) in an editorial to Excélsior in the days after the festival.[66] Monsiváis was, in fact, one of the few intellectuals who changed his position on Avándaro. Having initially described the festival as "one of the great moments of mental colonialism," he shortly afterward characterized the event as a "powerful, vital affirmation" of civilian participation. At the same time, however, he argued that Avándaro "signifies fundamentally a confused and inarticulate rejection of a concept of Mexico" which the PRI "confiscated, codified and incarnates."[67]

Yet for its participants, the native rock movement held out the hope of a rebirth at the symbolic as well as organizational level: a rejuvenation of symbols, language, and meaning, and a reorganization of class relations within society. As the liner notes from a Three Souls in My Mind album read, "For those who dig what's 'really happening' in rock, Three Souls in My Mind has much to offer. Their music is acid, heavy, aggressive. To

listen to it live is to feel oneself transported into another cosmic dimension.... They've said it before in another way: 'Rock isn't about peace and love; rock is about revolution.' Because rock is about rebirth."[68] Mexican rock directly challenged the state's capacity to monopolize cultural meaning and national identity. The rebirth referred to by Three Souls in My Mind was precisely a rebirth of youth consciousness in the demoralized and repressive context following the Tlatelolco massacre. Avándaro, for all of its shortcomings as a musical festival (which were many), had stood for something positive and reaffirming: the triumph of youth's participation on its own terms. This suggested a fundamental subversion of a hegemonic discourse that emphasized unity under a Revolutionary patriarchy.

Nonetheless, it was extremely difficult for the left to resist drawing a relationship between rock and imperialism. La Onda Chicana seemed to reflect the culmination of economic and cultural policies that subjected Mexico to U.S. domination. As an editorial in Excélsior entitled "Cultural Colonialism" read, "[I]f it is quite sad that a nation's soul is carried off—which amounts to a cultural conquest—it is sadder still, indeed shameful and abominable, that such a nation, of itself and for itself, gives up willingly, indeed joyously sells and turns over its soul.... Honestly, how far have we fallen into a colonialist situation, where we are but an appendage to a foreign culture?"[69] Or, as Luis Cervantes Cabeza de Vaca, a former student leader, proclaimed, "Imperialism is to be congratulated, for now it exports not only technology, industrial inflation, and our finished primary goods but also its breakdown, its own crises of a decadent consumer society."[70] The combination of rage against the previous political regime of Díaz Ordaz, along with the success of anti-imperialist movements in many parts of the world—especially Cuba and Chile—energized the search for a meaningful discourse among Mexican intellectuals. "Cultural imperialism" and "economic dependency" emerged as polemical terms in developing a critique of society and of international relations more broadly speaking. Moreover, this critique served as a means of legitimizing the very role the intellectual continued to play in Mexican political life. Thus in one extreme manifestation, a writer for the leftist magazine ¿Por qué? (which was later shut down by the government for its support of leftist guerrillas), described Avándaro as "a plan put into place by U.S. imperialism in a clearly evil alliance with the national oligarchy."[71] At the same time, the Echeverría regime directly embraced this critique as a strategy for co-opting it. "Without doubt," writes José Agustín, "Echeverría understood that in the new post-68 context the artistic, philosophical, and academic in-

telligentsia would suit his government very well, and he cultivated it."[72] Indeed, backlash against the rock counterculture served a crucial role in Echeverría's efforts to reclaim the state's symbolic role as cultural arbiter and defender of national borders.

The backlash catalyzed by the Avándaro music festival generated an intense debate in Mexico over what it meant to be "Mexican" in an age of increasingly transnationalized—"Americanized"—media representations. President Echeverría encouraged this polemic as central to a strategy of renewed nationalism and thus his regime's efforts to repossess control of a public discourse of national identity. A 1972 cover from the magazine Jueves de Excélsior captured this nationalist spirit. It showed a Mexican charro purchasing a Mexican flag from a vendor whose display included the swastika (symbolizing attacks by right-wing groups on his policies), the communist hammer and sickle (symbolizing attacks by left-wing groups), and a peace sign (symbolizing the cynicism toward all politics by the counterculture). The text reads: "I'm only interested in my own."[73]

The Crackdown

Whether Echeverría in fact authorized Avándaro or not, in the aftermath of the festival the state turned its administrative and repressive forces against the native rock movement at the levels of production, distribution, and consumption. While leftist critics had suggested the regime's cynical use of rock as a means for placating youth, Avándaro had revealed the political dangers of rock as well. From the regime's perspective, the sheer numbers that rock managed to organize must have made a deep impression; nobody had predicted the turnout at Avándaro. The possibility that the festival would turn into a political rally—whatever that might have looked like—were, for the most part, contained by the organizers' precautions. Yet rock music, at least in its live performance, clearly presented a situation for government forces where order could not be guaranteed. Rock "organized" people—or at least presented the opportunity for organizing—and proved it could do so, however tenuously, across class lines.

But the government's fear of rock as an organizing tool—rock's demonstrated capacity to bring together large groups of people from diverse social backgrounds—was only part of the story explaining the repression that soon followed. For a fuller understanding, we would also have to consider the ideological component: rock was no longer simply a metaphor of modernity but had become a metaphor for community as well. Rock music,

especially native rock music, suggested the possibility of reorganizing national consciousness among youth in such a way that the state was not only mocked but left out of the picture altogether.

The production and distribution of La Onda Chicana were immediately targeted by the regime. In effect, any song or image related to Avándaro was prohibited by the government. According to Herbe Pompeyo, a government memorandum was circulated to all radio stations in the capital "saying, or rather suggesting , that they don't make any reference to Avándaro, or play anything to do with Mexican rock."[74] This was reflected, for example, in the prohibition of a ballad entitled "Avándaro," recorded in anticipation of the festival's outcome. By direct order of the secretary of interior affairs, the song—which deals with the themes of community central to La Onda—was removed from radio stations, in spite of its popularity:[75]

We hardly know each other

But we feel the same way.

That's why we continue ahead

As brothers hoping for the best

To Avándaro, heavy place [lugar de onda ].

With music in our minds

Our hearts beating together

And filled with joy

All we groovy people go

To Avándaro, heavy place....

Rich kids [la gente fresa ] join the crowd

Searching for freedom in their words

And breathing in deeply.

Loving the clouds and hating war

They're going to Avándaro, heavy place.[76]

Meanwhile, at Radio Juventud the live transmission of the festival had resulted in a fine and the temporary imprisonment of the "responsible" disc jockeys. Certainly this in itself could have been expected; laws against abuse of foul language in the United States resulted in similar fines. But castigating the radio announcers, who after all were not directly responsible for someone else's bad language, was only part of the story. In addition, "the hip lexicon pioneered" at the station was declared "definitively over." In the future, disc jockeys would have to "express themselves correctly" or face revocation of their license.[77] This change conformed to another government memorandum that required self-censorship, thus avoiding "the corruption of language, proper customs, traditions, and national characteristics," as required by federal law.[78] Finally, the six hours of mate-

rial filmed by Telesistema would never reach the public, though at least two different underground films made by participants would later materialize.[79] At any rate, intentions to produce a live sound track of the festival were severely marred by the dismal technical quality of the material itself.[80]

The pressures against La Onda Chicana's production and distribution came precisely at the moment of an intensified marketing strategy by the transnationals. As Rafael González, an artistic director with Polydor at the time, explained to the rock magazine POP:

Look, the idea is the following: We've come to realize that a large amount of money leaves the country as royalties, author's rights, and other stuff.... My idea is to try to leave something for Mexico by starting a musical revolution [here].... [I]t's not exactly that we're being nationalistic but that we're trying to understand and support what is ours. Good or bad, it's ours. If we're lacking musically with respect to the level others are at, well we're going to push our [groups] to reach that level. I think what's happening in Mexico is similar to what occurred with the "English Wave."[81]

Polydor's advertising strategy in Mexico had begun to reflect this effort to elevate national rock onto an international plane. Plans, in fact, called for the creation of a separate Mexican rock catalog.[82] Indicative of this new direction was a poster-sized color advertisement included in Piedra Rodante featuring album covers by internationally acclaimed artists such as Jimi Hendrix, Crosby, Stills, Nash, and Young, the Rolling Stones, and both volumes from the Woodstock music festival. Partially protruding from each jacket sleeve was a "golden album," emphasizing the international impact of these selected records. Included in this presentation of "superstar" albums was La Revolución de Emiliano Zapata, as if among equals. The text of this poster advertisement succinctly summed up its content: "Esta es la onda gruesa" (This is the heavy scene).[83] In fact, there were already strong indications that all of the transnationals (not just Polydor) were moving in the direction of promoting Mexican rock outside the country, a strategy which coincided with industry reports that "heavier stress would be put on regional campaigns for specific artists rather than aiming at immediate worldwide impact."[84] Support for Mexican rock in southwestern parts of the United States would likely have been strong, where a growing population of Mexican American youth were also searching for their own cultural voice.

As a rule, the four transnational companies with subsidiary operations in Mexico benefited from a diverse musical catalog in addition to economies of scale, which allowed for greater latitude in their investment in native

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

rock. However, this also meant that La Onda Chicana constituted a smaller and ultimately less important part of their overall repertory; native rock could be eliminated without serious market repercussions. This is reflected, for example, in a breakdown of Polydor's 1971 catalog (see Table 1).[85] In fact, as the government could do little to prevent the continued distribution of foreign rock (short of banning it altogether), the companies lost little by cutting loose native rock contracts. Reflecting on Polydor's decision to drop plans for the development of a national rock catalog in the wake of Avándaro, Herbe Pompeyo commented, "[T]here was a certain amount invested [in La Onda Chicana], but fortunately Polygram [sic ] wasn't living from that. It was a project for the future. We continued to live off of other things.

We never placed all of our hope exclusively in the [native rock] project."[86] For the young artistic directors at Polydor Records, enthused by the international success of "Nasty Sex" (La Revolución de Emiliano Zapata), the direct and indirect pressures that restricted further exploitation of the counterculture's commercial potential represented the shattering of a vision of developing a national and international market for Mexican rock. Yet, as Herbe Pompeyo later reflected, "No one wanted to become a martyr in a struggle with the government" over the issue of native rock.[87]

Thus despite the nominal amounts of capital already invested in La Onda Chicana, especially by the transnationals, virtually all of the companies backed off under government pressure. Acting through the guise of the radio industry's chamber of commerce, the Cámara Nacional de la Industria de la Radiodifusión, which had played a consistent game of conflict and cooperation with the state since the 1950s, a memorandum was sent to every recording company asking that it "abstain from producing music interpreted at Avándaro, at the suggestion of the authorities at the Department of Interior Affairs."[88] None of this, however, prevented the companies from seeking to make some profit off the festival. But the resulting efforts were halfhearted and produced little follow-up. For instance, Polydor, having already geared up for a compilation album featuring studio versions of songs performed at Avándaro by its contracted artists, went ahead to produce Vibraciones del 11 de septiembre . Similarly, Orfeón produced a studio compilation album of its own entitled Rock en Avándaro , which used a photo-montage of the event for its cover—but only one of the bands featured had performed at Avándaro. No live sound track of the festival has ever appeared.

Another casualty of the crackdown was the countercultural magazine Piedra Rodante . Combining often-daring articles on drugs, politics, and the counterculture in Mexico and abroad with translated material from its parent magazine in the United States, Piedra Rodante quickly proved too much for a regime that sought to recontain the rock movement; after eight issues, the magazine was forced to shut down. Claiming a distribution of 50,000, the magazine not only aimed at a national audience but reached Central and South America, Spain, and the "Chicano youth of North America"—indicated as including the borderlands, New York, and Chicago—as well. As editor Manuel Aceves recognized, the survival of such an effort in Mexico "requires an atmosphere of liberty, both in an objective sense and at the level of consciousness," which he believed the apertura democrática under Echeverría would provide. "We sincerely hope we aren't mistaken about

this sexenio [six-year presidential term]," he wrote in an opening editorial.[89] During the eight issues of its existence, Piedra Rodante consistently tested the boundaries of the political opening offered by the new regime. An advertisement in its last issue provocatively queried, "How much freedom of the press exists in Mexico?" To fill this gap, the magazine offered "Youth's viewpoint about their own world versus that of adults. Without inhibition, shame, sweat, or reserve, the sole truth about drugs, politics, sex, rock, art ... a new type of journalism. Enlightened journalism. And enlightening.... The first long-haired news-journal."[90] But its bold testing of political and cultural tolerance—one issue boasted "40 pages replete with drugs, sex, pornography, and strong emotions"[91] —proved too much, especially in the context of an antipornography moralizing crusade spearheaded by conservatives.[92] While called to the attention of the ineffectual Qualifying Commission of Magazines and Illustrated Publications (the government censorship bureau for printed matter) in a letter by a member of Congress, the magazine nonetheless met a quicker fate than what would have been the arduous process of bringing the publisher to court under the rules of the commission: facing threats of physical harm, the editor simply ceased publication.[93]

At the same time that rock's commercialization was halted, live performances were also prohibited. Without concerts, there was little basis for sustaining a native rock movement. A scheduled concert at the National Auditorium featuring "original music" by seven Mexican bands and "lights, fog [that is, dry ice], slide projections, gifts, records, and posters" was forced to cancel.[94] The tocadas organized in the hoyos fonquis of lower-class barrios were especially targeted for police repression. As Joaquín López of La Revolución de Emiliano Zapata recalls the context of the hoyos fonquis around the time of Avándaro: "Well, the bands were popular and began to experiment with these large crowds; people began to call things into question. Potentially, a political hue and cry was in the making.... And I believe that exactly at that moment was when [government] repression began to shut down the hoyos fonquis, you see?"[95] Attempts to eliminate rock music in the barrios often led to direct confrontations with the authorities. As Ramón García recounts, "Once the press began to slam Avándaro, there was a total venting of anger directed toward the tocadas. There weren't even tocadas, because the granaderos would arrive and begin to beat up the musicians, carry them and their equipment off, and rough them up some more. And the truth is, people [in the audience] got out of hand ... and would take on the police, who just stirred them up more."[96] Determined to resist the government crackdown, a "Rock on Wheels" effort was organized in the

barrios. Mobile pickup trucks loaded with musicians cruised the streets looking for available spots to set up their equipment and perform in a flash, only to vanish when word of the police reached them. According to Ramón García:

[T]he response was so tremendous. We all knew these bands and whatever colonia it happened to be, people would come out and gather around. It didn't matter what the time was—morning, afternoon, or night—people came out and joined in. It was really a neat thing. We felt good, and so did the bands. If only a part of the band was playing, the others would pass around a collection hat to help out. It was really a cool thing.... But it didn't last all that long. The authorities quickly figured out what was going on and where the [performances] were taking place. And so it was, like, hear a little bit of music and then everyone took off.[97]

The rock critic Víctor Roura would later argue that "everything was shut down simultaneously"[98] after Avándaro. While largely true, to a certain degree this was also an exaggeration that has since lent itself to the myth of rock's total extinction after Avándaro. Though official sanctioning of live performances was out, not all official channels for rock gatherings were eliminated. For instance, in a possible indication of the regime's continued flirtation with rock as a means of reaching out to youth, the Museum of Anthropology in the summer of 1972 offered a presentation of the rock concert film Monterey Pop Festival . The screening, shown outdoors on the third night because of crowding, turned into "a mini-Avándaro [with] the three or four thousand kids who showed up behaving totally cool, without causing problems, just enjoying the music and the visual attractions."[99]

As Roura and others have pointed out, live rock went underground, but it by no means disappeared. In spite of the repression, this period gave rise to the reputation of the hoyos fonquis as the last bastions of live performance. Roura states that in 1973 "one could easily count some 150 rock groups who played in the capital of Mexico in different urban areas." In contrast to several years earlier, however, only a fraction of these ever made it into a recording studio.[100] Nonetheless, evidence of one such performance suggests the continued vitality of native rock and its significance as an integral element in the popular culture of the lower classes. In June 1972 a twenty-four-hour "festival without permits of rock outdoors" took place in the dry lake of Texcoco, on the margins of the capital district. A letter to the rock magazine México Canta responded to the festival with an enthusiasm clearly carried over from Avándaro: "Chicano rock's going forward, right on, with music in Spanish, totally alive. At Lake Texcoco there

was rock, rock, and more rock."[101] Moreover, and by means of comparison, in March 1975 another three-day concert took place at the Valle de Bravo, Avándaro site. This time, however, it was on the grounds of an elite sports club. Authorities had granted permission based on satisfaction of three restrictions: (1) that it be limited to the local population; (2) that it not turn into a rock festival; and (3) that no interview be given to the press prior to the event.[102] Clearly, live rock for the masses had become sporadic, underground, and often dangerous in its confrontations with the state.

The Question of Popularity

One of the most lasting issues concerning the collapse of La Onda Chicana centers on the question of its popularity with a mass audience. After all, if the majority of music was written and performed in English, perhaps it was only natural that its defenders quickly shrank away under the threat of government sanctions. Why defend a product that had only superficial mass support? Víctor Roura, for instance, argues that La Onda Chicana was largely inaccessible because English was the dominant mode of expression, and, in any event, the lyrics generally (but not always) failed to make a connection with everyday concerns. "Rock, therefore, was alien to the feelings of urban youth," he writes, "not so much for its rhythm, but for its inability to communicate."[103] This might make sense, except how then does one explain the popularity of foreign rock to begin with? Indeed, a more common argument for La Onda Chicana's disappearance made at the time (and since then) has been that the music itself was simply not very good. As Iván Zatz-Díaz recalls from a concert by the famed La Revolución de Emiliano Zapata, "I remember thinking actually that they were pretty awful! [laughs] ... There was nothing special about what they did. Nothing interesting. Nothing particularly good about it.... I remember, even by virtue of their name, they were kind of a controversial group.... In my opinion, they were pretty anodyne. Their music didn't stand for anything, really."[104]

This was not too far off from a reviewer's opinion of a concert by the same band for a middle-class Mexico City audience in 1971: "By the fifth song one gets the urge to simply leave, for its evident that the concert isn't going anywhere, that it's a disaster, an absolute failure and the group is a fraud.... What I don't understand is, why does the audience applaud? Could it be out of inertia, or worse still, out of ignorance? Do they really enjoy this music? This must mean that they've never heard really good rock."[105] And yet, as the former bassist with La Revolución de Emiliano Zapata him-

self relates somewhat incredulously, the group's hit song "Nasty Sex" was indeed popular: "Playing 'Nasty Sex,' one felt the power of Nasty Sex! [laughs] When you played that piece, the whole atmosphere changed ... It was a 'hit,' a strange hit.... Not a de jure hit, invented by the record company, but a real hit... that was popular all over the country.... You sensed it. When you played it, you felt the reaction of the audience."[106] Still, in an indication of the bitterness experienced by many band members over the failure of La Onda Chicana to consolidate itself, the former bassist with Love Army would comment in 1974: "The influence of the United States and Britain allows for little originality. Plus, there's a total lack of organization. All of this is based on the fact that we're an underdeveloped country. We lack musical maturity. I haven't encountered anything original. Everything is a poorly made replica of what is produced in other countries."[107] This echoing of the harshest critics of La Onda Chicana reflected the frustrations experienced after Avándaro, but at the same time it may suggest an overly narrow perception of the movement's acceptance on a national scale. If bands' musical creativity was itself inchoate, popular support for what the music stood for most definitely was not.

Latin American Protest Songs

The polemic against rock music was not limited to Mexico but was becoming widely expressed throughout Latin America. Rock was regarded by many on the left as the direct manifestation of an imperialist strategy to depoliticize youth while fortifying transnational capitalist interests. This leftist critique emerged in the context of the nueva canción movement and a renaissance of folk and protest music generally. While its intellectual and artistic origins were rooted in the cultural politics of earlier periods, the New Song movement was semiofficially launched at a 1967 conference held in Havana, Cuba, titled "Encuentro de la Canción Protesta" (Gathering of Protest Song). Reflecting a category of music attuned to the revolutionary and social protest movements that were occurring throughout the continent, New Song—referred to as nueva trova in Cuba, but also canción política (political song), canción popular (popular song), canción comprometida (committed song), and other such terms elsewhere—incorporated musicians from across Latin America. Especially prominent were Pablo Milanés, Silvio Rodríguez, and Noel Nicola (Cuba), Víctor Jara, Violeta Parra, and the group Inti Illimani (Chile), Mercedes Sosa and Atahualpa Yupanqui (Argentina), Daniel Viglietti (Uruguay), and Amparo Ochoa and Los Folkloristas (Mexico).[108] This "countersong," as one author dubbed

it,[109] variously used or combined traditional musical repertoires from Latin America to back lyrics that explored political, philosophical, and sentimental themes. It was an eclectic genre of music whose songs "questioned North American imperialism, economic exploitation, social inequality, and cultural alienation, along with themes that proclaimed a free and just future."[110] Pan-American solidarity—not with, but against the United States—was implied, if not overtly stated, in many of these songs.

As nueva canción gained ascendancy, commercialized popular music, especially rock, was increasingly slandered for its associations with imperialism.[111] This was ironic, because rock (especially the Beatles) had influenced some New Song musicians, such as Silvio Rodríguez. Nonetheless, in the context of the politically charged early 1970s, when various regimes throughout Latin America were openly hostile toward the United States and faced attacks from right- and left-wing elements, mass culture was readily conflated with imperialist designs and influence.[112] The critique of rock in part focused on the links between electronic music and economic and technological dependencies, ideas expressed, for example, in a roundtable discussion of music, nationalism and imperialism organized in Cuba in early 1973. As one participant commented, "I'm not against electronic music, but one has to be conscious of the technological element that creates dependency.... In this sense, one has to stimulate a genuinely Latin American culture with the elements at our disposal. It's necessary to be conscious that a culture weak in its creation, imprecise in terms of its authenticity, is always an easy prisoner for whatever type of imperialist penetration."[113] The various manifestations of "imperialist penetration" were suggested by an earlier conference also held in Cuba. In the "Final Declaration of the Meeting of Latin American Music," musical traditions were likened to raw materials that must be protected from relationships of dependency with the metropolises: "As with other deeply rooted popular and nationalist expressions, but with particular emphasis on music for its importance as a link between us, the colonialist cultural penetration seeks to achieve not only the destruction of our own values and the imposition of those from without but also the extraction and distortion of the former in order to return them, [now] reprocessed and value-added, for the service of this penetration."[114]

A clear example of this process of "value-added" marketing, which at the same time pointed to the complicated processes of transnationalism, was the impact of Simon and Garfunkel's song "El Condor Pasa." The song, credited as an "arrangement of [an] 18th c. Peruvian folk melody" was popularized by the folk-rock duo through their highly successful album Bridge over Troubled Water (1970). (Re)exported to Latin America at the start of

the revival in folk-protest music, Simon and Garfunkel were, ironically, responsible at one level for the commercial success of Mexico's own resurgence in folk music. As Luz Lozano reflected, "I've thought for a long time, 'How did that folkloric thing get started?' And I would say that it was with that song ['El Condor Pasa']. Or at least, it contributed a lot. It was the image that we had of [Simon and Garfunkel]. It was more than just them, like a triangulation: them, the Andes, and here, us.... I didn't know the song before [they recorded it]. I think that after that, the [movement] started to emerge here."[115] In Mexico (as in Cuba, Chile, and Peru) the political regime directly and indirectly supported the New Song movement and a shift toward folkloric cultural expression generally. Institutionalized performance spaces that once restricted rock, or were off limits altogether (such as the Palacio de Bellas Artes), now welcomed national and foreign New Song and folk artists. In one example, the Venezuelan-born singer, Soledad Bravo, whose work was described by Excélsior as an "impassioned [reflection] of themes rooted in Latin American folklore," was invited to perform at the Poliforum Siqueiros in Mexico City, a recently opened fine arts space named for the once-imprisoned, communist muralist Alfaro Siqueiros.[116] At the same time, the early 1970s witnessed a proliferation of music cafés called peñas , which offered a space for live folk-music performance. Unlike the cafés cantantes of the mid-1960s or the later hoyos fonquis, the peñas did not face the threat of arbitrary closure. On the contrary, the Echeverría regime went out of its way to express its support for this shift toward Latin American folk and protest song. As Federico Arana explains, "there was a clear and convenient symbiosis" between the folk-protest singers and the regime. "The proof that [the performers] weren't dangerous for the government is that they were never censured and never lost the government's support" (see Figure 17).[117]

The most ideologically articulate of the Mexican performers popularized during this period was the group Los Folkloristas, who recorded on the Discos Pueblo label, which became an extension of the group itself. The chosen name of the recording label reflected its broader mission: "[To] [g]ive diffusion to folkloric music and all the new forms of Latin American song, in their most genuine representations, exempt of all concession to the dominant commercialism... [To] [o]ppose the mounting imperialist cultural penetration [with] the voice of our peoples, as a necessity for identification and affirmation."[118] While Los Folkloristas had been in existence since 1966, not until the context of the early 1970s did they gain widespread recognition. To this the state lent a direct hand by donating space previously occupied by the National Symphony for the founding of Discos

Figure 17.

With official sanctioning, folkloric groups such as this one popularized

the indigenous sounds of the Andes and other regions in the early 1970s. Source:

Federico Arana, Roqueros y folcloroides (Mexico City: Joaquín Mortiz, 1988), 48.

(Photograph by Olga Durón; reproduced courtesy of Federico Arana)

Pueblo and an indirect one by making concert halls such as the Palacio de Bellas Artes available for performances.[119] Moreover, when a scheduled concert at the National Auditorium was canceled at the last minute by capital-district authorities, President Echeverría intervened personally, stating: "It's very important to me that those young people perform." Echeverría then proposed an additional concert by the group in celebration of Teachers' Day (15 May), an event that was carried live by Telesistema.[120]

As one informant suggested, "One can see how things coincided: El Condor Pasa, the peñas, Los Folkloristas. I mean, they're a group that has been around for a long time. They had plenty of gigs, but they weren't popular. It took the impact of something foreign for them to become accepted."[121] While her statement perhaps overly credits the foreign impact of Simon and Garfunkel, the commercial success of "El Condor Pasa" was not overlooked by the group itself. Before each performance of the song Los Folk-loristas "would give this veiled indictment of the commercial forces that had prostituted that wonderful music—meaning, the Simon and Garfunkel thing."[122] Iván Zatz-Díaz, a fan of the folk and New Song movement, recounted: "This sound engineer [my neighbor] ... his contention was, 'Say

what you will, but these guys [Simon and Garfunkel] have made South American music a thousand times more popular than Los Folkloristas ever could. So what's so wrong with that? It's a wonderful version.' And so on and so forth. And I kind of agreed with it, to a certain degree. I still like the Simon and Garfunkel version of 'El Condor Pasa' very much."[123] The radical ideological stance taken by Los Folkloristas was directly extended in their opposition to rock music: "[We are] [p]ledged to spread the best music of our continent, [we are] dedicated to the youth of our country who have discovered their own music [canción ], [we are] opposing it to the colonizing assault and alienation of Rock and commercial Music,"[124] the group announced in a statement.

A confrontation in Peru in late 1971 neatly illustrated this process of rock's politicization and demonstrates perhaps a broader generalization of the Mexican phenomenon. At the time, Peru was in the grips of a nationalist, military-led government that had come to power in a coup in 1968 aimed at preempting guerrilla victory by implementing a radical, leftist policy agenda. Carlos Santana was scheduled to perform eight benefit concerts in Lima for victims of a 1970 earthquake. The rock group was met by 3,000 fans and an official greeting by the mayor of Lima, who "gave [the band] a scroll welcoming them to the city." However, the powerful student union at San Marcos University, where the concerts were to take place at an 80,000-seat soccer stadium, protested that the scheduled event was "an imperialist invasion." Two days before the opening performance, the stadium stage mysteriously burned to the ground. With that warning, the Ministry of the Interior canceled the tour altogether. The band had their luggage and instruments confiscated, and they were promptly ejected from the country, accused of "acting contrary to good taste and the moralizing objectives of the revolutionary government."[125] By comparison, the folk-protest song movement was openly backed by the Peruvian military regime, which actively sponsored performances and media diffusion for national and foreign artists through its National Institute of Culture.[126]

The ramifications of the surge in folk-protest song and the Mexican regime's support for this movement were not the total elimination of rock but rather the further class and cultural bifurcation of rock's reproduction and reception. Native rock, as we saw above, survived by going underground. As Simon Frith might claim, it returned to its working-class roots, where it was sustained into the 1980s.[127] Foreign rock, on the other hand, though dashed by the impact of disco, was reinscribed as vanguard culture among the middle and upper classes, who continued to purchase albums and stay attuned to transformations in the rock-music world. At the same time, La-

tin American folk music and nueva canción also found a wide reception among middle-class youth, especially among students.[128] As Luz Lozano explained, "[The music] said things more clearly. You knew more of the lyrics from the songs. You knew more about the situation of peasants, workers, and so you liked it more. But that didn't mean you stopped liking the other [rock]. But you related more to the social thing. Besides, it was the fad."[129] What was problematic about folk-protest music in part, however, was that it shifted the attention of protest away from the government and toward the more abstract (at times, less abstract) notion of imperialism generally. Furthermore, it reinforced a concept of cultural authenticity that played directly into populist rhetoric, even while serving to disseminate traditional folk music to a broader audience. Finally, live performances reinscribed the boundaries of respect and discipline between audience and performer that rock worked to undermine. "Even when they're helped out with their elaborate sound equipment," writes Federico Arana, "the folk performers demand silence and composure from their audience. For rockers, in contrast, the more intense the audience participation, the better."[130]

The polemic against cultural imperialism also served the Mexican regime in its efforts to derail the incipient class-based alliance that native rock had sought actively to forge. Among the middle and upper classes both nueva canción and foreign rock encountered a wide reception at the expense of native rock, música tropical, and Mexican baladistas, all of which became to a significant degree associated with the lumpen, naco classes. As Iván Zatz-Díaz recalled the cultural polemic that developed:

There were always [student] factions who would reject one form of music or another. For the bulk of us there was a lesser or greater degree of eclecticism, but it was there nonetheless. We did listen to rock, we did listen to folk music.... The only music that I poo-pooed, and most of us poo-pooed, were say the cumbias and the boleros. That kind of stuff was the music of the nacos. And God forbid we would be listening to naco music, you know. I guess it also became kind of a 'naco' thing to do to listen to Radio Mil [which played refritos]. So we stopped listening to the Spanish version. We would only listen to the original versions on Radio Exitos or La Pantera. That was really much more of a clash, if you will, than whether you were listening to the music of imperialism or not. Because that was still an open question. Was John Lennon a revolutionary force, or an imperialist force?[131]

Jaime Pontones, later an important rock disc jockey in Mexico City, spoke of "studying Marxism like crazy and listening to rock, not exactly in secret but in my home, because all of my friends didn't listen to rock anymore;

they [only] listened to Latin American Music."[132] In an interesting twist, rock in Spanish (that is, refritos) had become inverted from its former status as "high culture" during the early 1960s to become "low culture," or naco, by the 1970s.

But for all of folk and protest music's pretensions of working-class solidarity and peasant struggle in the triumph over the bourgeoisie and imperialism, the music was simply not that popular among lower-class urban youth. This was true even in the case of Chile, a central player in the birth of the New Song movement. One study, for example, concluded that the music was most popular among students, professionals, and state employees; whereas housewives, workers, and the unemployed demonstrated the lowest disposition toward its consumption.[133] In Mexico, student organizers came to discover that folk protest music was not sufficient for attracting large audiences at rallies. As José Enrique Pérez Cruz recalled of student-organized protests during the 1970s: "Sometimes at the rallies, as there wasn't always a heavy draw with protest music, they also invited rock bands. And for those rallies a lot of people definitely came."[134] Indeed, this reflected a deeper class antagonism that the native rock movement had sought to transcend. Ramón García spelled out the impact the New Song movement had on those from the lower classes: "[T] hat was what the students listened to." He continued:

They listened to that type of music, and so that's where the separation [in the movement] occurred. Because a lot of students also were part of the rock movement, but because rock made them feel special. Maybe it was what they needed, that is, freedom. But they weren't so oppressed. But then when all that protest music came, then the rockers, we stayed on one side, and those who listened to protest music were another class of people. But for the rockers, none of that mattered. Because really, the rhythm didn't interest us very much.[135]