Chapter Two—

Getting to Buffalo

Late in his life Mark Twain advised the guests at his own birthday party, "If you can't make seventy by any but an easy road, don't you go." He might have said something similar about making Buffalo. As it happened, the road that led Samuel Clemens to that city in 1869 was hardly an easy one, even though it was in a manner of speaking paved by his soon-to-be father-in-law, Jervis Langdon, a circumstance which has led some commentators to maintain that Clemens paid a high price—a measure of his independence—for his passage.[1] Langdon, in fact, had the means to pave the way from Elmira to Buffalo literally as well as figuratively; although his fortune had been made in coal, he had helped underwrite a substantial paving contract in Memphis earlier that year. If the methods he used with his prospective son-in-law were more subtle than those he financed in Tennessee, they were nevertheless effective in bringing Clemens to nest within the range of Langdon's influence.

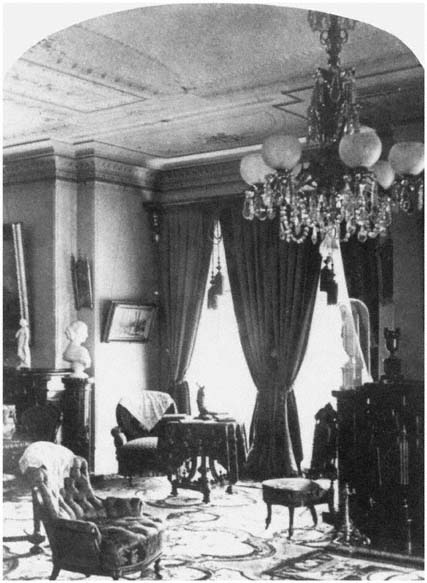

Nesting became Clemens's essential preoccupation as his obsession to reform his character subsided in the warmth of the Langdon's acceptance. Even before he and Olivia were formally engaged in February 1869, he began turning his attention, and hers, to an idealization of married life whose predominant qualities were stability, comfort, retreat, and tranquillity. For the itinerant lecturer living out of his valise as he shuttled from one town, and one hotel, to another, the notion of home was talismanic. "Make some more pictures of our own wedded happiness," he urged Olivia from Rockford, Illinois, "with the bay window (which you shall have,) & the grate in the living-room—(which you shall have, like-

The Langdons' home in Elmira, New York. (Courtesy Mark Twain

Memorial, Hartford, Conn.)

wise,) & flowers, & pictures & books (which we will read together,)—pictures of our future home—a home whose patron saint shall be Love—a home with a tranquil 'home atmosphere' about it—such a home as 'our hearts & our God shall approve'" (6 January 1869). Such pictures were acts of faith in a providential future that stood in sharp contrast to Clemens's past and present, if not to Olivia's. As he imagined it, it was to be a future in which the circumstances of his life dramatically changed while those of hers were perpetuated. That cannot be surprising. By the winter of 1868–69, Clemens was thirty-three years old and had been knocking about the world—paddling his own canoe, as he put it—for about half his life. He had lived on both this country's coasts as well as in its heartland, had traveled to the Sandwich Islands, Europe, and the Holy Land, and had been, he said, everything from a newspaper editor to cowcatcher on a locomotive. What he had never truly experienced as an adult was a sense of home.

He first visited the Langdon family mansion in the heart of Elmira late in the summer of 1868. The building itself must have

seemed to the self-styled vagabond a manifestation in brownstone of the solidity and stability of Olivia's upbringing, conditions that her semi-invalidism made even more emphatic. Stasis and security had been the facts of her life; movement and opportunism the facts of his. In asking her to marry him, Clemens believed and hoped that he was bringing his vagabondizing to an end, and he looked to Olivia as both the agent and the embodiment of that hope. On New Year's Eve 1868, he wrote her of the change he had already undergone. "The Old Year," he said, "found me ready to welcome any wind that would blow my vagrant bark abroad, no matter where—it leaves me seeking home & an anchorage, & longing for them.... I, the homeless then, have on this last day of the dying year, a home that is priceless, a refuge from all the cares & ills of life, in that warm heart of yours."

The brick-and-mortar home he envisioned himself providing the two of them was likewise to be an anchorage and a refuge. As Clemens imagined that home, it stood in juxtaposition both to his own chaotic past and to the contemporary "outside world" which he tended at such times to portray as nasty, venal, profane, and inclement. "Let the great world toil & struggle & nurse its pet ambitions & glorify its poor vanities beyond the boundaries of our royalty," he wrote Olivia. "We will let it lighten & thunder, & blow its gusty wrath about our windows & our doors, but never cross our sacred threshold." Part fortress, part tabernacle, such a home was, like Olivia's warm heart, to offer sanctuary and perhaps even salvation by virtue of a kind of sublime domesticity. "Only Love & Peace shall inhabit there," Clemens wrote, "with you & I, their willing vassals" (12 January 1869). Six weeks later he told her that his own visions of their future home "always take one favorite shape—peace, & quiet—rest, & seclusion from the rush & roar & discord of the world.—You & I apart from the jangling elements of the outside world, reading & studying together when the day's duties are done—in our own castle, by our own fireside" (27 February 1869).

Clemens no doubt pleased and moved Olivia with imaginings of this kind, but he was also beguiling himself, immersing himself ever more deeply in a religion of love whose altar was as truly the hearth as the heart. With a convert's fervor he declared himself forever cured of wanderlust, eager to forsake the road in favor of the

The Langdons' parlor. (Courtesy Mark Twain Memorial, Hartford, Conn.)

domestic castle. "I have been a wanderer from necessity, threefourths of my time—a wanderer from choice only one-fourth," he reassured Olivia—and persuaded himself. "Wandering is not a habit with me—for that word implies an enslaved fondness for the thing. And I could most freely take an oath that all fondness for roaming is dead within me" (24 January 1869). Just thirteen months earlier, Clemens had written Emily Severance of being "in a fidget to move," declaring that he "never was any other way" (24 December 1867). Now, as if from the ashes of his former selves— the knockabout, the adventurer, the skeptic, the comedian—a more stable, more mature, more unified self was to emerge. Clemens tended to regard this change in terms of the tension between movement and stasis and, for his own sake as well as the Langdons', to dramatize the sincerity of his commitment to a settled future. "I want to get located in life," he wrote Olivia. "I want to be married " (13 May 1869).

So settling down became a precondition of marriage and as such a prospect to be taken seriously, almost reverently—"the solemnest matter that has ever yet come into my calculations," Clemens confided to Mary Fairbanks, adding, "I must not make a mistake in this thing" (15 April 1869). The "thing" in question was not whether to settle—that had been a vague intention of his even before he met Olivia, and his dream thereafter—but where to settle and under what circumstances. Ironically for someone who had pursued as many occupations as Clemens had—printer, prospector, pilot, reporter, lecturer, correspondent—a big problem was which one he would follow as an established, married man. As it turned out, the answer was, none of them. He would continue to lecture from season to season, but he determined late in 1868 that he would substantially forego his former pursuits, buy an interest in a newspaper, and devote most of his energies to working as one of its editors. At the time, of course, he could boast a wide and varied experience as a journalist, experience that he might have offered as a credential, but full-time editing of a daily newspaper was something he had had neither the opportunity nor, very likely, the inclination to try.

How Clemens arrived at the determination to edit a newspaper, a determination that eventually carried him to Buffalo, is an uncertain if not entirely mysterious matter. Newly engaged and still

an itinerant lecturer-journalist as 1868 drew to a close, he had every reason to want to secure a steady income and little confidence that his writing alone would provide one. Mark Twain was no longer a merely local phenomenon; his Quaker City travel letters had earned him national attention, and he lectured during the 1868–69 season throughout New England and the Midwest to packed houses. But The Innocents Abroad did not appear until late July 1869, and in the meantime his notoriety, to say nothing of his talent, hardly seemed to him a bankable commodity. Even before he met Olivia, he had expressed doubt to Mary Fairbanks that he could support a wife of any, even the humblest, background solely on what he could earn as a writer. "Where is the wherewithal?" he asked her. "It costs nearly two [newspaper] letters a week to keep me . If I doubled it, the firm would come to grief the first time anything happened to the senior partner.... I am as good an economist as anybody, but I can't turn an inkstand into Aladdin's lamp" (12 December 1867). Although his fortunes improved and his reputation grew over the course of the intervening months, he hardly seems, during the winter and spring of 1868–69, to have entertained the possibility that he could free-lance a living sufficient to support the kind of home he was at the time urging Olivia to join him in imagining.

Becoming a newspaper editor was a compromise solution to the problem of vocation Clemens faced as he scrambled to position himself at the very end of the 1860s as a candidate for gentility. The decade just coming to a close had seen his wanderings describe a wide arc which carried him west from the Mississippi Valley and was now about to fix him in the East. The decade ahead, seen from the vantage point of the prospective bridegroom, was to be distinguished by a new rootedness and seriousness of purpose. The time had come for putting aside childish things, Clemens resolved; adulthood was upon him. "We are done with the shows & vanities of life," he wrote Olivia, "& are ready to enter upon its realities" (15 February 1869). Together they would become "unpretending, substantial members of society, with no fuss or show or nonsense about us, but with healthful, wholesome duties to perform" (21 January 1869).

Just where those roots were to be sunk and those wholesome duties—including the editing of a daily newspaper—performed

was a matter of some perplexity for Clemens virtually from the moment he began seriously to court Olivia in the fall of 1868. His anxieties took on a new urgency when on Thanksgiving Day of that year Olivia's parents provisionally accepted him as her fiancé. That night, after the Langdons retired, he wrote from Elmira to share the good news of his engagement with Mother Fairbanks, his principal confidante during the courtship. Although Olivia had at first insisted that he address her only as "sister," he said, "She isn't my sister any more—but some time in the future she is going to be my wife, & I think we shall live in Cleveland" (26–27 November 1868). With the breathless enthusiasm of a man struck anything but dumb by his own good fortune, he went on to propose a happy-ever-after ending to the romantic drama he had for several months been purveying in letters to Mary Fairbanks, an ending which depended strategically on her husband's position as a major shareholder of the Cleveland Herald : "I think you will persuade Mr. Fairbanks to sell me a living interest in the Herald on such a credit as will enable me to pay for it by lecturing & other work—for I have no relatives to borrow money of, & wouldn't do it if I had. And then we shall live in the house next to yours. I am in earnest, now, & you must not cease your eloquence until you have made Mr. Fairbanks yield."

This remarkable proposal offered an ingenious, one-swoop solution to Clemens's problems. It not only provided him with a vocation but also located him permanently within the sphere of Mary Fairbanks, whom he regarded as both advocate and architect of the regenerate self upon which he believed his happiness with Olivia so substantially depended. Mother Fairbanks had over the course of their correspondence become an important arbiter of Clemens's future, characteristically offering the kind of reassurance that promised now to minister to the insecurities he anticipated as a newlywed nestling. It may even be that his resolution to become a newspaper owner-editor took shape around the fortuitous possibilities that arose from the Fairbankses' situation in Cleveland, the combination of Mary Fairbanks's psychological support and her husband's ties to the Herald .

Whatever motives may have led Clemens to settle on settling in Cleveland, both Mary and Abel Fairbanks were apparently willing to play the part he assigned them in his Thanksgiving proposal. A

month after making that proposal, he visited them in Cleveland and sent a complementary letter back to Elmira—to Jervis, not Olivia, Langdon—announcing the satisfaction he took in Cleveland as a home. "I like the Herald as an anchorage for me, better than any paper in the Union," he wrote. As for his not-quite-formal negotiations with Abel Fairbanks: "He wants me in very much— wants me to buy an eighth [interest in the newspaper] from the Benedicts [his partners]—price about $25,000. He says if I can get it he will be my security until I pay it all by the labor of my tongue & hands, & that I shall not be hurried. That suits me, just exactly. It couldn't be better" (29 December 1868). The extraordinary luck that Clemens credited with guiding him to Olivia and with enabling him to win her love and her parents' approval gave no evidence of deserting him; the storybook courtship seemed destined for a storybook finish, in Cleveland.

With the turn of the new year, Clemens returned to the road, to the monotonous train rides, uncertain accommodations, and virtual absence of privacy that defined the lecturer's zigzag progress from town to town. "You can't imagine how dreadfully wearing this lecturing is," he wrote Olivia. "I begin to be appalled at the idea of doing it another season. I shall try hard to get into the Herald on such terms as will save me from it" (2 January 1869). But Cleveland would not be hurried. Twice in January, on the 19th and 23d, Clemens registered with Olivia his disappointment at having been prevented by the ill health of Herald co-owner George Benedict from pushing his newspaper negotiations ahead. By early February, when he wrote to inform his own family of his final acceptance by the Langdons and his formal engagement to their daughter, he was noticeably cooler about his Cleveland prospects. "I can get an eighth of the Cleveland Herald for $25,000," he said, "& have it so arranged that I can pay for it as I earn the money with my unaided hands. I shall look around a little more, & if I can do no better elsewhere, I shall take it" (5 February 1869). Just five weeks after having written so enthusiastically to Olivia's father, Clemens seemed on the verge of recanting his opinion that prospects for an anchorage "couldn't be better" than those offered in Cleveland.

By mid-February, while still lecturing in the Midwest, Clemens took to writing to Olivia about an alternative nesting site:

I look more & more favorably upon the idea of living in Hartford, & feel less & less inclined to wed my fortunes to a trimming, time serving, policy-shifting, popularity-hunting, money grasping paper like the Cleveland Herald.... I would much rather have a mere comfortable living, in a high-principled paper like the [Hartford] Courant , than a handsome income from a paper of a lower standard, & so would you, Livy. (13–14 February 1869)

Clemens's correspondence offers no explanation for his abrupt change of heart regarding the Cleveland Herald . He had visited the Fairbankses while on the lecture circuit in late January and seems then or shortly thereafter to have become disenchanted with the newspaper, if not the city. Of the Herald he wrote Olivia, "It would change its politics in a minute, in order to be on the popular side, I think, & do a great many things for money which I wouldn't do" (13–14 February 1869). On the other hand, Hartford's attractions, even apart from the rectitude of at least one of its newspapers, were manifold. Olivia and her family had personal ties of long standing there, many of them established through the Beecher nexus, which connected the city socially as well as spiritually with Elmira. Clemens would in fact accompany the Langdons to Hartford the following June to attend the wedding of Olivia's friend Alice Hooker to Calvin Day. Hartford served as the headquarters for the American Publishing Company, the subscription house which produced several of Mark Twain's early books and which was then in the process of preparing The Innocents Abroad . Because of that association, Clemens had already come to know the city and had made a particular friend there of Joseph Twichell, pastor of the Asylum Hill Congregational church.

As Clemens bewitched himself during the winter and spring of 1869 with visions of perfect domestic contentment, Hartford seems to have fixed itself in his imagination, and perhaps in Olivia's as well, as the likeliest place to live out the dream they were together conjuring. But his negotiations with the Courant 's proprietors, General Joseph Hawley and Charles Dudley Warner, proceeded haltingly and were characteristically tainted by condescension and evasiveness on their parts. On 14 February 1869 he wrote Twichell, "I think the General would rather employ me than sell me an interest—but that won't begin to answer, you know. I can buy into plenty of paying newspapers but my future wife wants me to

be surrounded by a good moral & religious atmosphere (for I shall unite with the church as soon as I am located,) & so she likes the idea of living in Hartford." Clemens was probably in earnest here in speaking of Hartford's morality, but at the same time he was plainly eager to motivate Twichell to take his part with the Courant owners. He could expect Twichell to be moved by his aspiring to the city's elevating atmosphere, particularly when he coupled that aspiration with an implicit promise to join the Asylum Hill church. Even more important, Twichell was the kind of partisan Clemens needed at the time to persuade solid citizens such as Warner and Hawley that they might without committing apostasy think of Mark Twain as a colleague rather than a clown. In a note to Olivia, he indicated Twichell's willing complicity in these matters by acknowledging "his kind efforts in forwarding our affairs" (15 February 1869).

Even with Twichell for an advocate, however, Clemens was stalled and put off by the reluctant Hartfordians. In describing his Courant transactions to Mary Fairbanks on 15 April 1869, he wrote, "I made proposals ..., & they wrote to one partner to come home from Europe & see about it. He was to have spent the summer or part of it abroad, but they say he will now get back in May. Therefore I am reading proof & waiting." The proof pages he was reading at the same time were of The Innocents Abroad , the book that would transform Mark Twain's still somewhat regional fame into genuine international celebrity. The Courant owners saw themselves negotiating with the latter-day Wild Humorist of the Pacific Slope, not the figure of wide renown and acclaim Mark Twain soon became. So, apparently, they waffled, and while they waffled Clemens wrote to Olivia of another, subtler, even rather perverse, impulse that fixed his hopes on Hartford. It had been the place to which he had retreated after meeting and falling in love with her in the late summer of 1868, the place in which, that September, he had experienced his intensest, most melancholy, most hopeless pining for her. "How could I walk these sombre avenues at night without thinking of you?" he asked.

For their very associations would invoke you—every flagstone for many a mile is overlaid thick with an invisible fabric of thoughts of you—longings & yearnings & vain caressings of the empty air for you....

I am in the same house [Elisha Bliss's] ... where I spent three awful weeks last fall, worshipping you, & writing letters to you.... But I don't like to think of those days, or speak of them. (12 May 1869)

It might have seemed particularly gratifying to Clemens to locate in Hartford and by doing so to transform the scene of his former misery and isolation into that of his domestic ascendancy. But Hartford would not be hurried. And while he endured the Courant proprietors' procrastinations, "reading proof & waiting," Clemens tried to interest himself in other berths. On 9 March 1869 he attended a lecture in Hartford given by Petroleum Vesuvius Nasby (David Ross Locke), who was not only a fellow humorist but also the editor of the Toledo Blade . Clemens met Nasby after the performance and sat up talking with him until the following morning. Among the topics of conversation, apparently, was Clemens's future, for later that day he wrote to Olivia, "Nasby wants to get me on his paper. Nix" (10 March 1869). The disinclination to join Nasby was much less emphatic just a month later, however, when he wrote his mother and sister confessing his indecisiveness on several fronts: "I don't know whether I am going to California in May—I don't know whether I want to lecture next season or not— I don't know whether I want to yield to Nasby's persuasions & go with him on the Toledo Blade—I don't know any thing" (ca. 7–10 April 1869).

He didn't know, further, whether or not to pursue matters in Cleveland while his prospects in Hartford remained uncertain. He wrote Mary Fairbanks on I April 1869 about the possibility of his visiting her that spring, together with Olivia and her mother. "If we do go," he said, "Fairbanks & I can talk business." By the middle of the month, however, he addressed her, perhaps a bit coyly, as if his chances of buying into the Cleveland Herald were not only dead, but long since dead. "Why bless you," he wrote, "I almost 'abandoned all idea' months ago, when Mr. Benedict declined to sell an interest.... I didn't want Mr. Fairbanks to take me into the partnership unless the doing it would help us both —not make me & partly unmake him. So I began looking around" (15 April 1869). A few weeks later he sounded as if he no longer considered settling in Cleveland a practicable alternative. "I had hoped," he told Mother Fairbanks, "that Livy & I would nestle under your wing,

some day & have you teach us how to scratch for worms, but fate seems determined that we shall roost elsewhere. I am sorry. But you know, I want to start right—it is the safe way. I want to be permanent. I must feel thoroughly & completely satisfied when I anchor 'for good & all'" (10 May 1869). He was, not altogether coincidentally, in Hartford at the time, and two days later he wrote Olivia an encomium to that city's loveliness: "The town is budding out, now ... & Hartford is becoming the pleasantest city, to the eye, that America can show." More than a year earlier he had expressed the same enthusiasm in a travel letter to the Alta California , where he declared Hartford "the best built and the handsomest town I have ever seen."[2]

His heart set on Hartford, Clemens did the best he could to be patient while he awaited the return from Europe of Courant co-owner Charles Dudley Warner, occasionally and unenthusiastically entertaining the idea of negotiating with the less attractive Hartford Post . "You see," he wrote Olivia, "I can't talk business to the Courant, for Warner is not home yet. I don't want to talk to the Post people till I am done with the Courant" (14 May 1869). When Warner returned in mid-June, matters proceeded swiftly and, for Clemens, unsatisfactorily. "Warner says he wishes he could effect a copartnership with me," he wrote Olivia, "but he doubts the possibility of doing it—will write me if anything turns up. Bromley of the Post says the 5 owners of that paper are so well satisfied with the progress the paper is making that they would be loth [sic ] to sell" (21 June 1869). There was no place in Hartford for Mark Twain.

The next day, burdened with the job of beginning the arduous hunt anew, Clemens contacted Samuel Bowles, editor of the Springfield, Massachusetts, Republican , about the possibility of buying a share in that newspaper. "Since I have some reputation for joking," he wrote Bowles, "it is the part of wisdom to state that I am not joking this time—I am simply in search of a home. I must come to anchor." Nothing, apparently, came of the effort, but its impersonal, almost random quality—Clemens hardly knew Bowles, and his inquiry has about it the air of a form letter—signals the writer's chagrin and, perhaps, his approaching desperation. Ironically, as Clemens discovered a few months later, Bowles

had been instrumental in discouraging Hawley and Warner from accepting him as a Courant partner.[3]

Within a week of the collapse of his Hartford hopes, Clemens wrote to his mother and sister about the prospect of resuming talk of partnership with Abel Fairbanks and his associates: "I shall probably go to Cleveland to-morrow or next day, but I doubt if I [shall] enter into my arrangement with the Herald, for Livy does not much like the Herald people & rather dislikes the idea of my being associated with them in business—& besides, they will not like to part with as much as a third of the paper, & Mr. Langdon thinks—(as I do,) that a small interest is not just the thing" (26 June 1869). Reopening negotiations with Fairbanks was a doomed exercise from the beginning, particularly because Clemens and Olivia had developed the habit of juxtaposing "the quiet, moral atmosphere of Hartford to the driving, ambitious ways of Cleveland" (SLC to OL, 15 February 1869). They had come to regard "the Herald people" as rather coarse and unseemly—that is, they harbored just the sort of reservations about them that the Courant people had about Mark Twain.

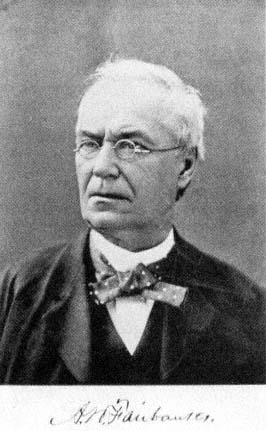

Moreover, for all the affection and esteem he had for Mary Fairbanks, Clemens felt little of either for her husband. At one point he even went so far as to compare her plight to that of "a Pegasus harnessed with a dull brute of the field." The Fairbankses were "mated, but not matched," he wrote Olivia, judging that circumstance to be "the direst grief that can befall any poor human creature" (10 January 1870). As they talked again of partnership in July and August of 1869, Abel Fairbanks acted to justify Clemens's darkest opinions of him. Exactly what occurred between the two men may never be entirely clear, but much of what happened can be reconstructed circumstantially. In June Clemens had written to his mother and sister, "I am offered an interest in a Cleveland paper.... The salary is fair enough, but the interest is not large enough, & so I must look a little further.— The Cleveland folks ... urge me to come out & talk business. But it don't strike me— I feel little or no inclination to go" (4 June 1869). That was before his negotiations in Hartford broke down; when they did, Clemens may have felt the need, if not the inclination, to deal with Fairbanks. "I mean to go to Cleveland in a few days," he wrote his

Abel W. Fairbanks. (Courtesy Mark Twain Papers,

The Bancroft Library)

sister on 23 June, "to see what sort of arrangement I can make with the Herald people. If they will take sixty thousand dollars for one-third of the paper, I know Mr. Langdon will buy it for me."

The details of the ensuing negotiations between Clemens and Fairbanks have gone largely unrecorded. By his own account, though, Clemens was driven to such anger by those transactions that in his frustration he got off a vitriolic letter to Elisha Bliss accusing him of endlessly putting off the publication of The Innocents Abroad . ("All I desire," Clemens sneered, "is to be informed from

time to time what future season of the year publication is postponed to and why" [22 July 1869].) By way of apology he sent another note on 1 August explaining the real cause of his outburst. "I wrote you a wicked letter," he told Bliss. "But ... I have been out of humor for a week. I had a bargain about concluded for the purchase of an interest in a daily paper & when everything seemed to be going smoothly, the owner raised on me. I think I have got it all straightened up again, now, & therefore am in a reasonably good humor again." The paper in question was clearly the Herald , given the timing of the correspondence, and the owner was just as clearly Abel Fairbanks. These conjectures are substantiated by a second apology Clemens sent Bliss on 12 August 1869. Referring to his sarcastic letter of 22 July, he said, "I was in an awful sweat when I wrote you, for everything seemed going wrong end foremost with me. I had just got mad with the Cleveland Herald folks & broken off all further negotiations for a purchase, & so I let you & some others have the benefit of my ill nature."

What seems to have "got it all straightened up" was a letter Fairbanks wrote Clemens on 27 July reviewing Herald income and expenses and continuing, "I should have been glad to had [sic ] Mr. L & yourself here, and let you examine more closely & I explain more fully, all that you might wish to know." Then, bringing the matter to a point, Fairbanks said, "Let me make a proposition, that I will take $50,000 for one quarter of the office—as it stands, assuring you there are no debts against it, & you become interested in all that is due it."[4] If, as Clemens claimed to Bliss on 22 July, Fairbanks had earlier that month "raised on me," Fairbanks's 27 July proposal would seem to have put things right again between them; that is, the offer of a one-fourth share of the newspaper for $50,000 was apparently consistent with proposals that Clemens had earlier entertained. At the very outset of his Herald negotiations, he had written Jervis Langdon, "Fairbanks says the concern (with its lot & building,) inventories $212,000.... He ... wants me to buy an eighth from the Benedicts ...—price about $25,000" (29 December 1868). Six months later he expressed his willingness to close a deal with the Herald proprietors "if they will take sixty thousand dollars for one-third of the paper" (SLC to Pamela Moffett, 23 June 1869). Fairbanks's 27 July proposal seems exactly proportional to the one Clemens initially considered ($25,000 for one-

eighth of the property) and only a bit more costly than the one he himself considered proposing ($60,000 for a one-third interest) in June. It may be, given these circumstances and the record of his comments about his own and Olivia's reservations, that Clemens's decision not to live in Cleveland was finally based on something other than finances. However, his apologetic letter to Bliss indicates that, his uncertainties about Fairbanks's offer having been "straightened up," Cleveland remained a likely site as late as 1 August 1869. What seems to have brought the Herald negotiations to an end is that Fairbanks evidently upped the asking price again sometime after that date. When he wrote to Mary Fairbanks on 14 August to explain his decision not to join the Herald , Clemens said of her husband, "We came very near being associated in business together, & I went home mighty sorry about that $62,500 raise."[5] There would not be, as there never had been, any talk of a "Father Fairbanks."

While he was learning through the spring and summer of 1869 not to trust Abel Fairbanks, Clemens came increasingly to depend on the counsel of a much more strategic elder, his future father-in-law. Taken together with other evidence of a similar kind, Clemens's 26 June letter to his mother and sister makes clear that Jervis Langdon was actively involved in his prospective son-in-law's business dealings: "Mr. Langdon thinks—(as I do,) that a small interest is not just the thing." The placement of the parenthesis here might lead a person to wonder which of the two was the more active. Fairbanks's suggestion that "Mr. L" accompany Clemens in examining the Herald 's books further substantiates the impression that Olivia's father was an acknowledged participant in the nesting enterprise.

However involved he may have been during its early phases, Langdon was never more clearly and centrally important to that enterprise than he was in promoting the dramatic turn of events that almost immediately followed the collapse of Clemens's negotiations with the Herald people in early August of 1869. As Clemens explained it to Mary Fairbanks later that month, "I ... received a proposition from one of the owners of the Buffalo Express who had taken a sudden notion to sell" (14 August 1869). There had followed "the bore of wading through the books & getting up balance sheets," he said, but "as soon as Mr. Langdon saw

Olivia's father, Jervis Langdon. (Courtesy

Mark Twain Memorial, Hartford, Conn.)

the books of the concern he was satisfied." Langdon seems to have discovered this opening, if not to have provoked it, and through the agency of his chief associate in Buffalo, J. D. F. Slee, to have played a big part in effecting the transaction. He also advanced Clemens half of the $25,000 he needed to buy a one-third share of the newspaper. On 13 February 1869 Clemens had written Olivia's mother, "I propose to earn money enough some way or other, to buy a remunerative share in a newspaper of high standing." Almost exactly six months later, on 12 August 1869, he used $12,500 from Langdon in closing his deal with the Express .[6] Two days later, in accounting for his preference for Buffalo over Cleveland, he wrote to Mary Fairbanks, "I guess it has fallen out mainly as Prov-

idence intended it should." To the extent that he believed in such inevitabilities, Clemens must have understood that his future father-in-law's influence extended even to the province of Providence.

Certainly it extended to Buffalo, where Langdon participated in the Anthracite Coal Association and carried on a considerable business. Buffalo was a relatively convenient five hours from Elmira by rail, closer than any other city large enough to support the kind of newspaper Clemens hoped to join. Despite these connections, however, it was clearly an afterthought, a last-minute alternative proposed by Jervis Langdon in the wake of Clemens's failure to come to terms in either Hartford or Cleveland. "I am grateful to Mr. Langdon," Clemens wrote Olivia, "for thinking of Buffalo with his cool head when we couldn't think of any place but Cleveland with our hot ones" (19 August 1869). He demonstrated that gratitude by leaping at the Express offer. Having been involved in negotiations with Abel Fairbanks well into July and quite possibly into August, he was nevertheless installed in Buffalo by 14 August and reporting to Olivia five days later, "It is an easy, pleasant, delightful situation, & I never liked anything better."

For all his professed determination to proceed deliberately in the question of where and how to settle—"the solemnest matter," he said, "that has ever yet come into my calculations"—Clemens ultimately jumped at an opportunity that he cannot have had two weeks to consider, and even at that declared his impatience with the "bore of taking a tedious invoice, & getting everything intelligible & ship-shape & according to the canons of business" before the deal could be closed (SLC to MMF, 14 August 1869). A partial explanation for his apparent impulsiveness probably rests in the observation that by mid-July he was recoiling, or rebounding, from disappointments in both Hartford and Cleveland. But the fuller truth may lie in recognizing that the Buffalo solution was proposed by the very man he had sought most to please in the matter from the beginning, Olivia's father.

Jervis Langdon had earned Clemens's gratitude by rather remarkably accepting him as Olivia's fiancé, even in the face of considerable advice to the contrary. And, given his daughter's preference, he had consistently shown his prospective son-in-law an open generosity that now included backing his purchase of a share in a

newspaper. Clemens's regard for Langdon was no doubt complex and at times contradictory, but some of its terms are relatively clear: his idealization of the senior Langdons, of their home and homelife, was in part an extension of his idealization of Olivia, and he tended to afford them the same uncritical enthusiasm he did her, at one point writing her father, "You are the splendidest man in the world !" (2 December 1868). It is not hard to imagine that he saw in the Langdons a whole and complete family, unlike his own, and that he saw in Jervis Langdon an adumbration of the father he had lost as a boy. Unlike Clemens's real father, though, Langdon was a success in business, a powerful man whose wealth seemed, in the light of Clemens's admiration, a natural consequence of his character. Langdon helped to establish in Clemens's personal mythology the figure of the charismatic captain of industry, a figure which was to appeal to him throughout his life. Fully a generation before Henry H. Rogers stepped in to advise Clemens on matters of business and to put his affairs in order, Jervis Langdon was establishing the paradigm that Rogers and other of Clemens's substantial friends were to mirror.

Langdon's wealth at once reflected and enhanced his power, with his prospective son-in-law as with many people who came within the sphere of his influence. In seeking his "anchorage," however, Clemens was at first determined to pay his own way, thus avoiding a potentially compromising indebtedness to Langdon or to anyone else. "I have no relatives to borrow money of, & wouldn't do it if I had," he had told Mary Fairbanks (26–27 November 1868). To Langdon himself he declared his intention to underwrite his purchase of a newspaper interest exclusively through "the labor of my tongue & hands" (28 December 1868). Once the process of finding an anchorage was underway in earnest, he reasserted that intention in letters to his mother and sister, telling them on 5 February 1869, "I don't want anybody's help," and later that month elaborating, "My proposed father-in-law is naturally so liberal that it would be just like him to want to give us a start in life. But I don't want it that way. I can start myself. I don't want any help. I can run the institution without any 'outside assistance'" (27 February 1869). By the time his prospects in Hartford had died and he was trying to rekindle his enthusiasm for Cleveland, however, Clemens had arrived at an altogether different attitude toward his proposed

father-in-law's liberality. If the Herald people would reasonably part with a one-third share of their paper, he wrote his sister, "I know Mr. Langdon will buy it for me" (23 June 1869). By the time Langdon did finance his purchase of an interest in the Buffalo Express , Clemens seems to have accustomed himself to the discovery that there were advantages to paddling his canoe in tandem with a generous backer. On the day he arrived in Buffalo he wrote Olivia, "I owe your father many, very many thanks, ... & I will ask you to express them for me—for if there is one thing you can do with a happier grace than another, it is to express gratitude to your father" (8 August 1869).

Clemens's deference to Langdon in matters pertaining to the course of his future, though, ultimately arose from a source even more powerful and more characteristic than gratitude, indebtedness, or admiration. He felt guilty at the prospect of breaking that exemplary family circle by stealing Olivia away from it. In a letter to her of 23–24 December 1868, he portrayed his intention to marry her in just those terms:

I just don't wonder that it makes you sad to think of leaving such a home, Livy, & such household Gods—for there is no other home in all the world like it—no household gods so lovable as yours, anywhere. And I shall feel like a heartless highway robber when I take you away from there—(but I must do it, Livy, I must —but I shall love you so dearly ... that some of the bitterness of your exile shall be spared you.)

On 13 February 1869, their formal engagement just announced, he began a letter to Olivia's mother on the same note: "It is not altogether an easy thing for me to write bravely to you, in view of the fact that I am going to bring upon you such a calamity as the taking away from you your daughter, the nearest & dearest of all your household gods." Three weeks later he resumed his confession in another letter to Olivia by depicting, or imagining, the response to news of their engagement by certain friends of the Langdons: "These folks all say, in effect, 'Poor Livy!' I begin to feel like a criminal again. I begin to feel like a 'thief' once more. And I am . I have stolen away the brightest jewel that ever adorned an earthly home, the sweetest face that ever made it beautiful, the purest heart that ever pulsed in a sinful world" (5 March 1869). Given his penchant for overdramatization, especially in treating his courtship of

Olivia, it would be easy to take too seriously Clemens's self-adjustment at times like these. Still, in so consistently portraying himself as criminal, thief, and robber, he betrays an attitude that seems at least to have colored his early relationship with the Langdons.[7] "I feel like a monstrous sort of highwayman," he confessed to Mary Fairbanks, "when I think of tearing her from the home which has so long been her little world" (24–25 December 1868). Imagining himself the interloper, the plundering outsider, he had reason to seek atonement and accommodation.

That attitude, together with the frustration that followed the collapse of his negotiations in Hartford and Cleveland, may well have left Clemens particularly susceptible to Jervis Langdon's ministrations on his behalf. In large part because of those ministrations, he found himself quite abruptly settling in Buffalo. The road that carried him there in early August 1869, might have seemed an easy one at the time; certainly it was convenient to Elmira. But it had opened to him only after a series of circuitous dead ends had taken their toll on his patience and self-esteem. Now he was determined to use his berth at the Express to establish his credentials as a man of steady and industrious habits. "It is an exceedingly thriving newspaper," he wrote Elisha Bliss. "We propose to make it more so. I expect I shall have to buckle right down to it" (12 August 1869). For their part, his new partners brought their own enthusiasm to the transaction, describing Clemens in a 16 August editorial as "an acquisition ... upon which any newspaper would congratulate itself" and informing their readers that they would "hereafter ... be regularly and familiarly in the enjoyment of the humor of the most purely humorous pen that is wielded in American journalism."[8] Mark Twain would become a fixture, a staple, in Buffalo. "'Buffalo Express' is my address hereafter," he wrote Bliss; "shall marry & come to anchor here during the winter" (12 August 1869). Clemens had found his harbor and, he believed, his vocation.