IV—

INDIA AND THE "COMMERCIAL" PERIOD

20—

India

(1958)

By the mid-fifties Rossellini's career had reached rock bottom. His films with Ingrid Bergman had not only failed at the box office, but had failed critically as well. True, the French were calling them the heralds of a new age of filmmaking, but the people with the money were not listening. As we saw in the last chapter, Bergman, too, was growing dissatisfied with being Rossellini's "property." Nor was he insensitive to their problems, as he explained many years later:

That was a very particular moment in my life, because I was married to a great, great actress. The point was that I risked too much and we were hated, I don't know why. Our films were not at all successful and we had big problems as we had three children. She was aware of the problems and she thought it would be wise to return to the industry just in order to save the material means of our life. I appreciated that thought very much, I believed it was wise. Unfortunately I was absolutely unwise myself and I did not want to be the husband of a great star. So very peacefully, very quietly and with a very full understanding and tremendous human compassion we decided to break. It was very hard, because we loved each other and we had three children. It was very, very painful.[1]

Now at his personal and professional nadir, Rossellini traveled to Africa, South America, and finally, in June of 1956, to Jamaica, where he was to make "The Sea Wife" with Richard Burton and Joan Collins. On his arrival in Jamaica, however, he discovered that the producers had changed the script he had written, presumably to avoid censorship problems; Rossellini immediately abandoned the project. (It was subsequently filmed by Bob McNaughton and released in 1957.)

Then the idea of going to India occurred to him. As he told reporters in Paris:

The producers don't want to give me any more work because what I'm saying doesn't interest them any more. That's why I accepted the offer made by the Indian cinema. I have been given carte blanche: in India I'll be able to study the atmosphere, analyze the major problems, make the most of the magic, fakirist and philosophic tradition, juxtaposing it with contemporary voices which are rising and becoming important. It will be, in short, the great Indian civilization, in all its grandness, its past and future which will take me by the hand and trace the subject which has not in any way been imposed on me. It will be difficult to be a neorealist in such a fabulous atmosphere, but I will certainly find many similarities with things I have already treated while developing Italian themes.[2]

It must be remembered that these remarks were made for the benefit of the press and seem intended to pander to their perhaps less-nuanced sense of things—in film journals, for example, Rossellini had been denying for years that he was a neorealist. Nevertheless, the remarks offer an interesting summary of his thoughts as he was about to depart for India. He had always been fascinated by foreign cultures, but by this time he was becoming especially interested in what was beginning to be called the third world. Here he could closely examine a single traditional culture, but, more importantly in view of his later overwhelming interest in science and modern technology, he could try to depict a vibrant test case, an actual battlefield between tradition and technology. He was also immensely drawn to Ghandi, who had once stayed in his home in Rome for a few days, and he told Victoria Schultz in Film Culture that "Ghandi was the only completely wise human being in our time of history."[3] He was also impressed by Nehru, Ghandi's successor, and spoke of him as "an extraordinary man" and "a saint." Jean Herman, Rossellini's young French assistant, makes it quite clear in the article he wrote for Cahiers du cinéma during the filming that the final product was to be a kind of social analysis of India, and certainly not merely the personal impressions of an auteur: "This will be the objective summing-up of ten years of freedom, of ten years of work, and of all the snares and traps that lie in wait for India today."[4]

Rossellini told a reporter for the New York Sunday News that this new film was to be "a takeoff on one of my earlier films, Paisan , which made money in the United States,"[5] and, in fact, the films are similar in their episodic structure and method of filmmaking. In India, as in postwar Italy, Rossellini went from one end of the country to the other, filming interesting sights, on the lookout for promising material. As Herman tells us, the director came to India with the rough outline of an idea in his head, but, as always, he allowed the specifics of the events, people, and places he encountered to determine the final product, making him add, delete, and change continuously.[6] Another aspect of his filmmaking practice here that is important for his later career is the fact that the project originally took the form of short documentary films for Italian and French television, from which he would then cull the best material for release as a commercial film. At this point, however, Rossellini still sees television princi-

pally as a means to an end, a kind of dry run (and source of necessary funds) for what he really wanted to do.

A further similarity with his earlier, pre-Bergman practice, is his insistence on the incorporation of "real life" into his film. As in films as chronologically far apart as La nave bianca and Francesco , he tells us proudly in the titles of India (the film is also widely known as India '58 ) that "the actors, all nonprofessional, were chosen in the very locations in which the action takes place." To some extent the result is again, paradoxically, to destabilize the codes of realism, preventing our acquiescence in the illusion and always keeping before us the sense that what we are seeing has been made . He also returned to his previously standard practice of observing someone he might choose to be in the film in order to memorize his "natural" actions, then, when he became stiff and artificial in front of the camera, Rossellini would "build him up again, teach him to act the way he was before you began teaching him to act."[7] He was so taken by the successful adaptation of his old methods to a new subject matter that he told the French journal Cinéma 59 that his future plans extended to South America, especially Brazil and Mexico. His remarks clearly foreshadow the great didactic project to come:

I will send teams of young people into each country, and they'll do an initial scouting. They will include a writer, a photographer, a sound man, and a filmmaker, who will be the head of the team. And this is how I'll proceed: I'll make an index for each country, and I'll study, along with my collaborators, their problems, food, agriculture, animal raising, languages, environment, etc. As you see, the task of a geographer and ethnographer. But it won't remain merely scientific, and will give each spectator the possibility of discovery. The art will only be the end point of this preliminary work. My job will be to make a work which will be a poetic synthesis for each country. . . .

I have tried to use this method abroad, but I could also use it in Europe. I've returned from India with a new way of looking at things. Wouldn't it be interesting to make ethnographic films on Paris or Rome? For example, a wedding ceremony. . . . Well, we need to rediscover the rites on which our society rests, with the fresh outlook of an explorer who is describing the customs of the so-called primitive tribes.[8]

The relation of this film to the rest of Rossellini's oeuvre is complex. Before it come the intensely introspective, expressionist fiction films made with Bergman, which seem to make only the slightest nod of acknowledgment toward external, surface reality. Immediately after it come the films of the only really blatant, self-consciously commercial period in his life, beginning with General della Rovere (1959) and ending with Anima nera and "Illibatezza" (both 1962). Yet Jean Herman is correct, I think, in regarding India as a "synthesis of the Rossellini oeuvre" that merges the exteriority of Paisan with the interiority of Voyage to Italy .[9] India itself, as Rossellini pointed out, is an amalgam of these two realities:

The Indian view of man seems to me to be quite perfect and rational. It's wrong to say that it is a mystical conception of life, and it's wrong to say that it isn't. The truth of the matter is this: in India, thought attempts to achieve

complete rationality, and so man is seen as he is, biologically and scientifically. Mysticism is also a part of man. In an emotive sense mysticism is perhaps the highest expression of man. . . . All Indian thought, which seems so mystical, is indeed mystical, but it's also profoundly rational. We ought to remember that the mathematical figure nought was invented in India, and the nought is both the most rational and the most metaphysical thing there is.[10]

In this remark Rossellini is clearly trying to reinscribe the fantasy (here, mysticism) of La macchina ammazzacattivi and Dov'è la libertà? into a wider, now more inclusive, realist aesthetic. Instead of being opposed, fantasy will now become a subset not of realism, exactly, but of rationalism. This latter term, which in some ways will help Rossellini elide the contradictions of realism, will soon come to be paramount in his remaining films.

Rossellini's understanding of India is accomplished in four individual episodes, each with its own main "character," "story," and location, the whole bounded on both ends by a factual frame that, especially at the beginning, provides the information necessary to put the individual episodes in an overall context. (In itself, the episodic, fragmented nature of the film implies that our understanding can be only partial and fragmented.) An interesting, active dynamic is immediately set up between the frame sequence, which is marked by fast cutting, zooms, and quick camera movements—obviously appropriate to its concentration on the city life in Bombay—and the inner sequences of life in the villages, which are generally much slower, comprised primarily of long takes, medium shots, pans, and minimal cutting. Appropriately, the physical movement which the film celebrates is registered in two different ways, depending on location. In the opening urban sequence it is conveyed through the artificial excitement of montage. Where movement exists in more natural settings, however—for example the flight of birds and the scurrying of monkeys through the forest—it is also highlighted, but significantly, by following it through pans.

Our own movement, from the frame to the interior stories and back again, is itself thematic. The voice-over tells us in a dramatically heightened, pulsating way at the very beginning of the film that "the first thing that astonishes you [in Bombay] is the crowd: tens, hundreds, thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands, perhaps a million people who come together like the incessant current of a river." Rossellini seems to be suggesting that, while first impressions are important, they must be seen through, in order to come to any understanding of the reality of the country. Yet, at the very end of the film, after the four internal, personalized stories have been told, we are put back in the same place, back into the middle of the city that we have not seen since the beginning, back into the fast cutting and zooming on the mass of swarming humanity, while the voice-over murmurs, as though mesmerized, one last phrase: "And still, the crowds, the immense crowds." We wonder if we, as outsiders, are forever condemned to be prisoners of our first impressions, which of course are always a product of our own culture, the culture we thought we left behind.

The dynamic between the framing sequence and the internal sequences also underlines the presence of the filmmaker in the whole process. In the opening sequence of India , a thoroughly un-Rossellinian style of editing assails the viewer: the cutting is even faster, and more self-conscious, than it was in the early La

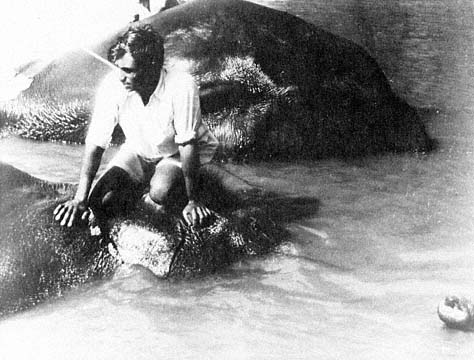

nave bianca , so indebted to Eisenstein. While the voice-over bombards us with facts, the very presence of the massive statistics, despite their "objectivity," paradoxically seems to underline the fact that they were compiled and put together by someone , and thus from a particular point of view. At the same time, the visuals jump along quickly, often cutting in perfect unison with the verbal sound track (for example, in the exciting series of quick cuts that accompanies a string of rhyming verbs), further underlining the presence of a mediating mind. In the inner sequences, on the other hand, there are moments of quick cutting when the narrative demands it, but the sequences are primarily composed of long-take shots by an absolutely immobile camera. Here we see simple acts, like the ritual bath of a young engineer, or the attachment of a log to a chain, then the chain to an elephant—acts often long and drawn-out, unquestionably real—that are accomplished in a single take. (Also, of course, the lack of cutting is appropriate to the subject—in this case the elephants, the effect of whose ponderous, immense bobbing would be totally lost if the sequence were fragmented into a jazzy montage.) Though these inner sequences sometimes seem to offer themselves as privileged, direct glimpses of a "true" reality, the fictionalization of the episodes, as well as the return of the frame tale at the end, work against this.

The manner of presenting the inner tales and their information is complicated as well, for once they have been factually and contextually launched by a third-person voice-over, all, in one way or another, are told from a first-person point of view. Thus, each episode seems to be balanced between the desire to convey a certain amount of abstract information and the related, but different, desire to put this information in a human context. Though one might object that the individualizing of the portraits takes away from the typicality of the film as a documentary, it is clear that seeing things from a single individual's point of view, and, even more importantly, hearing "his" words (in Italian, of course) concerning that reality is what makes the film so memorable. The language used by each principal character is so utterly direct and spare that it carries the charge of a poem by William Carlos Williams. The old man of the third episode, for example, tells us in a stately, measured tone (with enormous pauses between most of the sentences and accompanied by a perfect correlation between the words and pictures):

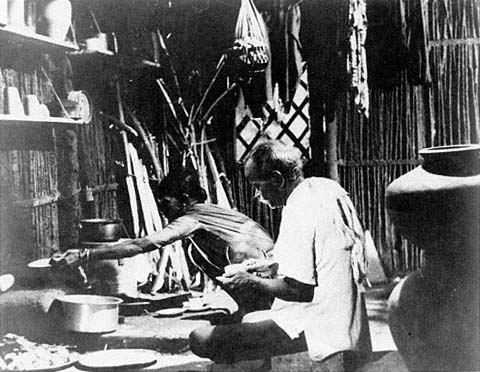

I am eighty years old. I have always lived here but the forest is still rich, appealing and full of secrets. Especially at night when it resounds with the fantastic love songs of the tigers. The jungle is the temple in which their rites of love are celebrated. When I awake at the rays of the sun, there is an explosion of joy which surrounds me. My wife and I do not need to exchange many words. Our gestures and looks are enough to express our unchangeable, daily solidarity. It has been a long time, after all, that our mutual duties have been shared between us. What else is there to say?

The entire film, in other words, has been subjectivized, and on several levels at once. The filmmaker has, for his part, made an attempt at objectivity, at getting beyond the Western self: Claude Baurdet, a reporter for France Observateur , wrote at the time, "The director insisted that he needed an intermediary with a true understanding of the lives of the Indian peasants, in addition to cinematic

knowledge, in order to complete his project."[11] Rossellini also knew, however, and freely admitted, that everything that we see in the film, no matter how objectively obtained, has been filtered through his own (Western) consciousness. He told Godard in a famous interview for Arts (which Rossellini later claimed Godard had made up) not that the audience should learn the truth of India, but that they "should leave the theater with the same impression that I had while I was in India."[12] As a reporter for the New York Times pointed out, the film is successful precisely because Rossellini was so forthright about his own romantic notions concerning India, and he quotes the director to the effect that his ideas about the country were "gathered from books and newspapers . . . [and] are a rather stewy mixture of Ghandism, passive resistance, Jawaharlal Nehru, land distribution, the five-year plan, and spiritualism."[13] Even more important in this regard is the self-consciousness apparent in the title of the television series itself: in Italy, where it was broadcast between January and March 1958 in ten episodes of eighteen to twenty-nine minutes each, it was called "L'India vista da Rossellini" (India Seen by Rossellini), and in France, where it was shown between January and August of the following year, it was called "J'ai fait un beau voyage" ("I Had a Fine Trip"); in both cases, the mediation of the filmmaker's consciousness is clearly signaled.[14]

In important ways, then, this entire film stands opposed to the prevailing film fashion of the time, cinéma vérité. Rossellini felt, for one thing, that this kind of "direct cinema" could never achieve anything more than an undigested depiction of a not necessarily significant surface reality. He told the editors of Cahiers du cinéma in a 1963 interview that, unlike the cinéma vériste who forgets that the camera is only a tool, the real artist is one

with a precise position, his own artistic dream, a personal emotion, who gets an emotion from an object and tries to reproduce it at any cost, who tries, even if he has to deform the original object, to communicate to someone else perhaps less sensitive, less subtle, his own emotion. You can see how the author enters into all this, how his choice is determined, how his style becomes the essential element of expression.

He spoke of being upset, bored, and angry at the screening of his friend Jean Rouch's La Punition , and when asked how his own film differs from cinéma vérité, he responded: "There is an enormous difference. India is a choice. It's the attempt to be as honest as possible, but with a very precise judgment. Or, at least, if there's no judgment, with a very precise love . Not indifference, in any case. I can feel myself attracted by things, or repulsed by them. But I can never say: I'm not taking sides. It's impossible!"[15] As we shall see, Rossellini forgets the impossibility of not taking sides when his subjects become historical figures. Here in India , however, he understands the problem full well, and as Bruno Torri has explained, the film was clearly meant to be "a harmonious and life-giving account of the interaction between what was observed and the point of view of the observer."[16]

Another site of the film's self-awareness is its fascination with rhythm of all sorts, visual, verbal, musical, and thematic, which Rondolino attributes to Rossellini's recent experience with opera and especially with the oratorio Giovanna

d'Arco al rogo . A marvelous correlation exists between the visuals and the sound track (both its verbal and its musical components) that seems unique in Rossellini's films, and this rhythm provides the pleasure inherent in all forms of rhyming, repetition, and fulfilled expectations. The musical score itself stands out, but for once in a Rossellini film, not because it is annoying; composed almost solely of various forms of native Indian music, it seems utterly organic to what we are seeing. The score is augmented and complemented by sounds that come from the location—thus, the bells worn by the elephants insist on the immensity of these animals' presence in the sound track as well. (Herman tells us that the bells are put on the elephants because the animals are so quiet moving through the jungle that a human could easily be hurt without some advance warning.)

The voice-over commentary (anathema to cinéma vérité) also reminds us that the film was made from a particular point of view, but once the basic information is presented in the opening sequence, it becomes less obvious. Rossellini had, in fact, told the reporter for the New York Times in 1957 that the images were more important than understanding the dialogue, for "a healthy picture did not need more than a little bit of explanation here and there." However, those few who have been lucky enough to see the only copy available in the United States—an unsubtitled black-and-white print owned by the Pacific Film Archives at the University of California at Berkeley—know how important the Italian voice-over actually is to a basic comprehension of what is going on. It would be more accurate to say that, once the basics of the narrative line of each episode are grasped through the commentary, the images supply a resonance of their own that transcends the merely verbal.

India 's emphasis upon the image is accompanied by a greatly enhanced sense of pleasure in composition that we last saw in some of the stylized sequences of Fear . Throughout his life Rossellini maintained that he was completely uninterested in "pretty pictures," and that, in fact, he always avoided them, but the evidence of India , at least, belies this claim. Many images are obviously meant to be experienced aesthetically rather than merely as neutral carriers of information. The best example is perhaps the astounding shot of the young engineer who takes his ritual bath in the artificial lake created by the dam he has helped to construct; the confluence of ancient tradition and modern technology is obviously the point of the shot, but our pleasure goes beyond this realization. The camera holds absolutely steady for what seems like minutes, creating a frame that is split in two by an unbroken horizon line, above which lies the untroubled sky, below the water, below that the land. The young man walks out into the water after shedding part of his clothes, bathes, then walks back onto the shore, picking up his clothes and walking out of the shot before there is a cut or a single movement of the camera. Examples such as this could be multiplied many times.

Let us now turn to a closer examination of the individual episodes of the film. The old themes are still present: for example, the concern with problems of communication and the attendant respect for diverse cultures are in evidence right from the opening title which, in an attempt to avoid a reductive Western "orientalism," shows the name of the film (and the name of the country) in Ital-

The elephant-bathing sequence from India (1958).

ian and English, in Urdu, and with the words, Matri Bhumi (Mother Earth), occupying the third position. Many conversations not absolutely crucial either narratively or informationally are presented at various times in three of the official native languages of India. The animal motif, so closely connected in his earlier films with the woman-as-victim theme, also reappears, but now it represents the relation between man and nature. In the terms of the perhaps too-neat formulation he gave Godard, "I wanted to show [in Fear ] what there is of the animal in intelligence, and in India '58 , I showed what there is of intelligence in the behavior of an animal."[17]

The first fully developed episode, which takes place in the jungle of Karapur and centers on the relation between the professional elephant drivers and their elephants, is a visual delight. We learn that "the elephant is India's bulldozer," and chuckle to see the elephants knock trees down and then carry them away. The narration switches to the first-person point of view of one of the drivers, who tells us how much elephants have to be fed, and, in a superb sequence, we witness the care that has to be taken every day to give the elephants their baths when it becomes too hot to work any longer. The elephants loll and roll over in the water, as languorous as immense cats. When a company of puppet players arrives in the village, the young man becomes interested in the owner's daughter, and from this moment on, the elephants (who are also "falling in

love") and the two young people are overtly compared in order to point up the harmony between man and nature that Rossellini finds in India. The young man goes to the schoolteacher for a formal letter to his father, asking him to speak to the girl's father in order to arrange their marriage. This scene and the one following (of the schoolteacher acting as mediator between the two fathers) are recorded entirely in the Indian language of the region, with no specific explanation provided in Italian. By the end of the episode, the young man tells us that the pregnant elephant must go away from the male halfway through her pregnancy, in the company of another female elephant who will minister to her needs, and because the demands of his work do not allow him to accompany his pregnant wife to her mother's, she, too, must be accompanied by another female.

The second episode, like the rest, begins with specific information that later will be put in more personal, individualized terms. Here the emphasis is on water. We start at the Himalayas, India's principal source of water, and learn about reincarnation, the sacredness of the Ganges, and the holy city of Benares along the way. The central focus of the episode, however, is the immense dam built at Hirakud, largely by grueling human labor. Our protagonist is a young engineer who has been working on the dam for seven years but who must now leave because his job is finished. He and his wife, we learn later, were originally refugees from East Bengal, due to the division of Pakistan, and since their child was born at Hirakud, they have come to look upon it as home. The husband seems sad but reconciled to the prospect of moving, but the wife complains throughout, refusing to understand, and at one point after a farewell party, an argument breaks out that ends with him pushing her violently to the floor.

The emphasis throughout is on the engineer's consciousness, and it is clear that this episode of the film, though visually magnificent, depends heavily on its verbal component to be understood. The young man makes one more trip back to the dam, where thousands upon thousands of unskilled workers—mostly women—carry rocks and dirt atop their heads, basket by basket, in their seemingly Sisyphean task. We learn from the engineer's voice-over narration that some 435,000 people work at the job site, and 175 died building the dam. But, "Before with the floods, if we had to build a monument to the dead, it would have taken a list as long as the dam itself to inscribe the names of all of them."

The chief theme of this sequence is the advent of technology into a traditional culture. Rossellini clearly believes in technology—and this belief will increase dramatically as the years go by—but at this point he is still concerned about its misuse. As Jean Herman tells us at the end of his article:

Rossellini came here with his head stuffed with questions. He was afraid of the dangers represented by the [West's] too-clean-hygiene, the button-you-press-which-solves-all-your-problems, the books-on-how-to-teach-five-year-olds-in-five-days, the pills-which-save-you-from-eating.[18]

The director is clearly fascinated by the conflict raging in the mind of this young engineer between the desirability of modern technology and the demands of the traditional culture. In one powerful sequence the man is wandering amid the giant spools of electric cable and immense electrical transformers, and, in a voice made to reverberate like an echo chamber, he thinks: "Electricity. Magic.

The old man and his wife eat breakfast in a scene from India .

Everything can be explained. All it takes is to think. There is no magic. There are no more miracles. Knowledge. Mystery. No more mystery. Knowledge. Hirakud." In the next sequence, however, we are pulled in the opposite direction as he observes a ritual burning of a body on a funeral pyre and thinks aloud that, while death is difficult for those who have been left behind, it must be very good to be able to dissolve completely into nature. A satisfying synthesis is achieved in the shot described earlier, when the young man takes his ritual bath in the artificial lake that has been created by the dam. The family leaves the next day with the cart carrying the few pieces of their furniture; stretched out behind them is the overwhelming presence of the dam. The episode ends with a resonant, self-consciously composed shot of a file of workers moving off to the right, who are rhymed visually by different-colored stones in the curb in front of them; the camera pans right, away from the couple, to "discover" the workers, then remains immobile as they file out of the frame, one by one.

In the third episode we move to the land where the rice grows. Our protagonist here is an old man who we see in his daily rituals: making obeisance to the sun when he rises, having breakfast with his wife, giving advice to his sons. We see vaguely "documentary" material that serves to advance the narrative not a whit, like a woman breast-feeding her infant, and the old man's wife packing

the sides of their hut with mud, reminiscent of similarly "aimless" sequences as far back as La nave bianca . The old man tells us, in a soft-spoken, simple prose that is thoroughly convincing:

The only thing that is left in me is the need for contemplation and for that there is only one place on earth that can satisfy me: the jungle. I love my cows. They are beautiful and strong animals. I always bring them with me. . . .

When I am alone in the jungle I feel strongly the presence of nature and it seems to me that little by little I become part of it.

He says that, even though he knows that the tiger he hears will not hurt him, still he is afraid.

Then one day his jungle peace is destroyed by the presence of three trucks full of men looking for iron; the old man has often heard of this substance, but believes it is a myth. And here Rossellini shows us the less pleasing side of technology. The noise of the motors causes all the animals to become upset (monkeys and vultures are juxtaposed in the editing in a clear foreshadowing of the next episode); in the commotion, the tiger is attacked by the porcupine, and, as the old man knows too well, only a wounded tiger is ever dangerous. The tiger finally does attack a man, as the old man feared; the cycle is complete when the prospectors decide to go on a tiger hunt for this dangerous animal. The old man asks, "Why kill? Isn't the world big enough for everybody?" In the last sequence of the episode, he sets a fire to convince the tiger to seek refuge in another part of the jungle, away from the hunters.

In the final segment Rossellini moves completely into the world of the animals by making one his protagonist. Again, a problem is posed and a piece of information supplied; this time it is the inverse of the water of the second episode—the devastating effects of drought. The camera tilts down from the "sky of steel" to reveal a man and his trained female monkey wandering through the parched desert. The man collapses and, as he slowly dies, the monkey tries vainly to protect him from the vultures that are gathering to attack. The sequence becomes a veritable feast of camera "trickery," with rhythmic pans, faked shadows, and suggestive editing all used to exacerbate the sense of danger. The sequence continues much longer than one might normally expect of a wordless event like this, and the effect is to make us even more aware of the elaborate rhythmic choreography of camera, physical shapes, light and shadow. In a chilling image, vultures bounce along the ground, their enormously long wings fully outstretched, but seemingly more in order to frighten than to propel them into the air. The monkey finally gives up her quixotic act of protecting her dead master and breaks loose from the chain that holds her, as the editing becomes faster and faster and the vultures close in—again, all through the suggestivity of the cutting rather than through any actual proximity between the monkey's master and the vultures about to attack.

This sequence is followed by a quick cut to the fair toward which the man had been traveling when he collapsed. Characteristically, we are not told that this cut signifies the continuation of the monkey's narrative; we do not see her or hear of her, in fact, until the location and the environment of the fair have been fully placed before us. Only after many shots of the various performers

does the monkey come into the frame, and we are left with the impression, as always, that the individual story is not important in itself, but only as a vehicle for presenting whatever reality has been found and/or constructed in the encounter between the filmmaker and the country. Then the film cuts suddenly to furious cart-and-oxen races, which apparently are part of the fair but, again, are narratively unmotivated and remain unexplained by the laconic voice-over.

The monkey has come to the fair out of training or instinct and, lacking a master, pitifully goes through her paces, doing what "she is used to doing, picking up coins that she does not understand the use of." She is unable to provide for herself because she has lost her connection with nature, and, at the same time, wild monkeys threaten her because she is deeply tainted with the smell of man. We see unhappy shots of her sleeping on the temple steps like a bum, forlorn and hungry, while her more natural relatives send up a howl at her presence. Finally, she is rescued by a new owner, and the last image we see of her is in her "new life" as a performer on a miniature trapeze. The voice-over gives only the barest information and is painfully reticent and noncommittal about how we are to read this image of her swinging back and forth above the awed crowd. Again characteristically, Rossellini refuses to move to a simplistic closure regarding this final example of the relationship between man and animal. Most viewers will find the image degrading, I think, and while we may have been intended to take this training as one more example of the wonder of man's skills, the monkey seems to represent a message counter to that which has gone before. Man and animal, and by extension all of nature, are in close harmony in India, but the two realms are distinct, finally, and must remain so. The monkey is awkwardly suspended between the world of men and the world of animals, and not comfortable or even able to take care of herself in either one. The monkey's split between nature and culture is, however, emblematic of the human condition, Rossellini seems to imply, especially in terms of advancing technology. In fact, in the 1959 Cahiers du cinéma interview he said, cryptically, that the monkey's division is "exactly the story of all of us. It's the battle that we're engaged in." The episode ends immediately after this shot, with a close-up on the human faces that file past the camera on their way out of the small circus tent. We then go back suddenly to the final short piece of the framing sequence, which completes the decisive return to human beings. For Rossellini the humanist, it is good that men and animals can be in such a harmonious relationship, finally, because it is good for men.

The film was first presented at the 1959 Cannes festival, out of competition, and was well received; its commercial release in Italy did not come until June 1960, however, and by April 1961, the film had grossed only 15 million lire—another box-office failure. This time, at least, the general critical reaction was favorable. The French appreciated the film, of course, especially Godard:

India goes against all standard cinema: the image is only the complement of the idea which provokes it. India is a film of an absolute logic, more socratic than Socrates. Each image is beautiful, not because it is beautiful in itself, like a shot from Que Viva Mexico , but because it's the splendor of the true, and because Rossellini takes off from the truth. He has already departed from the place most others won't even reach for another twenty years. India gathers

together the entire world cinema, like the theories of Reimann and Planck gather up geometry and classical physics. In a forthcoming issue, I will show why India is the creation of the world.[19]

Even Rossellini's most bitter Italian critics, those who had pilloried him during the Bergman era, welcomed him back to the fold, anxious to "forgive" him. In Mida's words, "with a wipe of the sponge, he has wiped out all the earlier mistakes, all the uncertainties of an obvious decadence."[20] More recent critics, like Baldelli, however, have mounted a serious attack:

The eye isn't enough when an exact politico-cultural preparation and a complete immersion in the circumstances are lacking. Rossellini shortens and at the same time confuses the historical distances from the moment he begins to see India as a gigantic example of his usual themes: a boundless South crawling with "paisans" and the fabulous presence of antique temples, a remote past which is always equal to itself, a perpetual seat of equilibrium between nature and history.

He complains that Rossellini shows the irresistible, harmonious onward march of technology that in actuality proceeds at the expense of the masses. He faults Rossellini's devotion to the passive nonviolence of Gandhism, the whole film becoming, for Baldelli, little more than a transference of the ideals of Saint Francis to the Indian masses. Finally, he objects to the film's neglect of topics like starvation, the caste system, religious superstition, and the inability of the masses to read.[21]

Of course, Baldelli is right. Seeing the film, however, is a profound and moving experience that perhaps covers up, but also redeems all its shortcomings at the same time. Of the films of Rossellini's that are not available for public viewing, this is perhaps the greatest loss, not only for the proper understanding of Rossellini's career, but for the proper understanding of the potential of cinema itself. Andrew Sarris has called it "one of the prodigious achievements of this century,"[22] and he is only overstating by a little.

Before concluding this chapter, it may be useful to describe in more detail the major shift that was taking place in Rossellini's thinking at the time, which is signaled by the new emphases, especially on technology, apparent in India . The principal text will be his interview with Fereydoun Hoveyda and Jacques Rivette published in the April 1959 issue of Cahiers du cinéma . It is here that the director first spells out his increasing interest in the powers of human reason, an interest that will remain submerged in the more blatantly commercial films that immediately follow, but will soon after become nearly obsessive.

In the interview he professes first of all to be amazed that modern abstract art could have become the "official art," given that it is the least intelligible. The reason for this, he believes, is that man is being forgotten, that he is becoming just a cog in a gigantic wheel. This situation must be seen in historical terms, however, as part of an eternal alternation between long periods of slavery and all too brief moments of freedom. But today things are worse because now we are held by a "slavery of ideas." The cinema, television, radio, through their sensationalism, all bear part of the responsibility for this sorry state of

affairs. Instead of pandering to the worst in man, we must try to understand him and his world. Most of all, we must avoid the smiling, false optimism that leads us to alcohol, tranquilizers, and the psychiatrist to avoid every possible anxiety in the world.

Rossellini says, furthermore, that we must begin to reestablish the rapport among various nationalities that existed immediately after World War II, and the cinema has a significant role to play in this attempt, as does the newer medium of television. He speaks approvingly of his own television series on India, for "there I could not only show the image, but speak and explain certain things." At this point in his career, however, it is still the cinema that is paramount, and, in light of his later didactic films, for the somewhat surprising reason that it can be more emotional, finally, than the more factual material prepared for television: "Perhaps my television broadcasts will help people to understand my film. The film is less technical, less documentary, less explanatory, but because it tries to penetrate the country through the emotions rather than statistics, it allows us to penetrate it better. That's what I think is important and what I want to do in the future."[23]

Rossellini's concerns have not yet been broadened, or made more subtle, and they are obviously marked by their fifties' origin. Yet, here in embryo, we can detect the founding beliefs of the final fifteen years of his cinematic practice. In 1959, though, they were little more than beliefs. Ironically, Rossellini will next, for virtually the first time in his career, begin to make cinema the old-fashioned, conventional way—though not, certainly, what he had begun calling the cinema of "holdups and sex." His goal of freeing himself forever from the demands of the commercial cinema of sensation will finally be fulfilled, but only after five more years of struggle.

21—

General della Rovere

(1959)

As we have seen, Rossellini's own voyage to India had an enormous impact on his artistic sensibility and his view of what the cinema had to become. However, India was a box-office failure as well, and, in fact, represented one of the lowest financial points of his career. His situation in 1958 was thus an awkward one: he had yet to find the alternative financing of television that he would successfully exploit for the last fifteen years of his life, yet he no longer had the lure of Ingrid Bergman to insure a steady stream of prospective investors, ever hopeful for a hit.

There had always been offers to do films that were more overtly "commercial," though little documentation exists to tell us just what these projects were. The actor Vittorio Caprioli recounts how one night he and the producer Morris Ergas were having dinner with Rossellini and Sergio Amidei when Caprioli mentioned that Diego Fabbri had just finished writing La bugiarda for him and that Ergas should produce it. The eager Rossellini immediately suggested that he direct the picture, but Ergas said no. Amidei then mentioned a sketch by Indro Montanelli he had recently seen in the Milanese newspaper Corriere della Sera; Ergas and Rossellini expressed interest, and the film was on its way.[1]

Montanelli's sketch, followed closely in the film, tells the story of a petty thief and gambler who is forced by the Germans to masquerade as General della Rovere, an important Italian military leader and Resistance figure who has been secretly killed by the Germans while attempting a clandestine landing. Bertone, the gambler, is put in prison in order to discover the identity of the leader of the Resistance, for while the Germans know that they have him in the same jail, they do not know which prisoner he is. Bertone becomes so absorbed by the

role he is playing that at the end of the film he willingly goes before the firing squad with his "fellow" partisans rather than reveal the identity of their leader.

The screenplay was written principally by Amidei, Diego Fabbri, and Montanelli,[2] but it is unclear how closely it was followed by Rossellini. Just after the film was completed, the director was claiming rather grandly:

I don't need traditional methods to make a film. For me, the inspiration comes on the set. My work on the scenario of General della Rovere consisted in tracing out the general lines of my story and of imagining, very close up, the personality of my character. I have no preconceived notions before I begin filming, and it's the first shot of a film which determines the entire work. It is then that I really feel the rhythm that I must give it, which leads me to imagine the thousand things which are the essence of my film. I want to arrive at the film location with a new feeling.[3]

Five years later he bluntly insisted, that "The only thing that really existed of the film was the screenplay which I read quickly and then put aside during the shooting. Many people, including the producer, have taken credit for the organization of that film, but this is the real story."[4]

It is ironic that Rossellini should have been so intent on claiming authorship of a film that he so obviously disliked, both during production and later. It was not the last film he was to make out of sheer necessity, but it was the first. Even the rather forced humor of the Totò vehicle Dov'è la libertà? had been closer to his heart. Years later, in fact, he named General della Rovere as one of the two films (the other being Anima nera ) that he was actually ashamed of having made, because "it's an artificially constructed film, a professional film, and I never make professional films, rather what you might call experimental films."[5] In another interview conducted at the same time, he explained why he undertook the project in the first place, relating his motives to the new discoveries he had made about himself in India:

I had decided to change [my methods of filmmaking] completely. And so I said to myself: "In order to change and to put my new ideas into operation, I'll need at least six months, or a year," and so I tried to find something by which I could save my life. Well, there were a lot of people who were very happy that I had finally given in, that I had obeyed, that I was following the rules (though I wasn't). Instead, it took some five or six years to get started in a serious way, and that was a bad surprise.[6]

Even during he shooting he was uneasy. He told the interviewer for Arts magazine, "I would reproach my film for being too well constructed, for relying on the continuing development of the story." His enormous ambivalence shows, as he continues: "I'm afraid that my film is going to be a big success and, in spite of everything, I hope it will be. Was it perhaps a tactical error for me to have made it? I don't really know yet, because I'm still too much in it. I have been trying to imagine the pros and the cons, the dangers for the continuation of my research and the possibilities that it holds out to me. Let's wait and see.[7]

It is clear now that General della Rovere was not his kind of film, despite the superficial similarities to past successes that made some critics ecstatic that Rossellini had seen the light. Even Massimo Mida, who heralded the film as opening

up a renaissance in Italian cinema through its return to the past, and who saw in it the end of Rossellini's period of "involution," nevertheless realized that the director was unenthusiastic and that the final product was little more than a tired rehash of his earlier triumphs. Mida admits that General della Rovere "was not the film that Rossellini would have wanted to direct and was not, at that moment, his ideal film," and quotes instead a significant array of "projects closer to his heart": Brasilia, The Dialogues of Plato, The Death of Socrates, Tales From Merovingian Times, Bread in the World.[8] These titles indicate clearly where Rossellini wanted to be, and where, after a few more years of frustration, he would be.

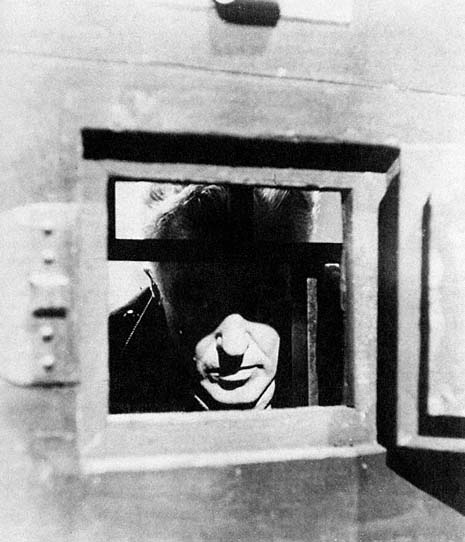

Of all his films, it is only General della Rovere that can and must be judged by the conventional standards of the "well-made" film.[9] It is immediately likable in a way that many of his other films are not, but it contains barely a hint of the depth or resonance of a film like Voyage to Italy , say, and ultimately registers as little more than a bravura piece of acting. Rossellini had been able to prevent Bergman from "acting" through the sheer force of his will over her, but De Sica, an immensely successful star by this point (and as a director perhaps even more prestigious than Rossellini), could not be so easily restrained. Nor is it certain that Rossellini even tried to control him; having already accepted the idea and the script, he perhaps may have given in on this point as well. For Rossellini, "saving his life" took the form of reassuring producers that he could make a conventional film if he wanted to, making it clear in the process that the other films, however "poorly made" they seem on the surface, were, for better or worse, like that on purpose. In fact, General della Rovere contains more than a few excellent passages of conventional filmmaking that can stand with anything produced by the most "professional" of Hollywood directors.

One very significant aspect of the film is its return to the war and the Resistance, the scene of Rossellini's earlier victories. Strangely enough, it was one of the first Italian films to go back to that period, and in the wake of its financial success, a host of others quickly followed. At the time, Rossellini told a reporter for the New York Herald Tribune that he had returned to this subject because he felt "that it is necessary to re-introduce the great feelings that moved men when they were confronted face to face with final decisions."[10] In addition, there was now a whole new generation who needed to have these anti-Fascist values inculcated in them, young people who had had no direct experience of fascism. Unfortunately, these values have not been reinvigorated in the film and seem less than fresh. Rossellini's earlier theme of coralità reappears, but when mixed with his more recent emphasis on the individual, the result is a dynamic of leader and followers, which is closer than ever to the superficial psychologizing of the standard Hollywood product.

If General della Rovere marks a return to the content of the earlier films, in formal terms it is a return to the dramatic and narrative conventionality of Open City , not to the dedramatized distanciation of Paisan . Thus, the film's plot, narrative thrust, and suspense have all been greatly intensified. In this film, things definitely happen . Lots of things. Nor are the dramatic moments undercut, as usual in Rossellini's films, but are lingered upon and played for all

they are worth. Similarly, our relationship with the protagonist is now completely changed, and Rossellini's typical distance separating the spectator from the character, a distance that seemed to foster a morally preferable sympathy rather than a manipulative and emotionally constricting identification, now disappears. Some contemporary critics praised the increased psychological subtlety of the film's characters, and it is true that we get more time to come to "know them as people." The method of accomplishing this, however, is that of the banal film that relies on the transparent, "telling" detail to "reveal" characters, as when the German officer straightens his tie before receiving della Rovere's real wife at the prison. The "richness" of the psychological portraits is, in fact, based on an amassing of clichés. Other critics applauded the director's newfound sense of humor, but, again, it is a humor that is totally predictable and painlessly digestible, accompanied by little wit and less irony.

Rossellini went even further to make his new backers happy. According to Variety , the entire film was shot in thirty-one days for a mere $300,000.[11] Rossellini later said that, even though he had been given twelve weeks for the shooting, he began July 3 and took the finished, edited film to the Venice film festival on August 24![12] And the reward for his capitulation? General della Rovere was awarded the Golden Lion (along with Mario Monicelli's La grande guerra ) at the festival, and in its initial release grossed over 650 million lire, more than forty times the box-office receipts of Voyage to Italy .

Professional, "accomplished," a well-made, if rather straightforward, adventure story of the Resistance. But is it? As one might expect from a film by Rossellini, all is not what it appears on the surface: "They thought I had given in, that I had obeyed, that I had followed the rules (which I hadn't.)" In spite of the work's apparent seamlessness and conventionality, in other words, there remain recalcitrant elements that refuse to fit. These elements have proven particularly frustrating for critics bent on finding organic unity, especially since they occur in a work that seems so utterly direct and obvious. First, there is the film's blatant artificiality, especially in terms of its lighting and its sets. The lighting, for example, is cast in the stylized film noir mode of a movie like Fear , rather than the serviceable, "natural" flatness of Open City . Furthermore, Rossellini is now shooting in a studio, and the familiar rubble has been manufactured by his crew. The sets are not obviously artificial, of course; they are, simply, just not real. Of a piece with the slickness of the rest of the production, they are in fact "well done," and one critic even complimented Rossellini on doing a better job at capturing the "true" Milan on a Roman studio set than any other director had been able to do in the real city.

Again, there is a strange dynamic at work. For, intercut within the scenes shot in the studio (often by means of a wipe, an ostensibly more "artificial" means of transition that is used much more frequently in this film than in his previous films), we are shown real footage, or at least "real" in the sense of taking place in a real, preexistent location: marching soldiers, bombing raids, the landing of the true General della Rovere via a submarine and a raft (a sequence shot by the director's son, Renzo), and the truck on the road. Events depicted in this "real" footage happen with the quickness that in Paisan added powerfully to the sense of seeing a real event happen before our eyes. There are

A "well-made film": Vittorio De Sica peers out from his

jail cell in General della Rovere (1959).

also moments early in the film where presumably "real" people, that is, non-actors seemingly unaware of the camera's presence, are standing around watching wrecking crews knock down actual bombed-out buildings, in a De Chirico—like reprise of early scenes from Germany, Year Zero . All of this contrasts continuously with the blatant unreality (because so tidy and managed ) of the studio locations, especially the unconvincing bombing raid on the prison.[13] The result, once more, is an extension of that revelatory dialectic, in muted form, that we saw at work earlier between the conventions of cinematic realism and the de-

piction of reality itself. Here, however, the film's code of realism is not threatened or invigorated by any perception of the potentially dangerous incursion of this reality. Hence, the clash of the footage shot on the set and those few bits shot on location is more reminiscent of the comic self-reflexivity of La macchina ammazzacattivi than of the exciting, unstable mixtures of Paisan . At the same time, the dominance of the code of realism in this film affirms the utter impossibility of a true return to the earlier films, no matter how devoutly wished by the director's supporters, at least in anything other than an ironic or self-aware mode.[14]

Yet even this minor disjuncture between realism and reality operates thematically in General della Rovere . One scene, for example, when a group of partisans still at liberty meets specifically to discuss whether or not the man in prison is the true della Rovere, is shot using rear projection, with actual snowy streets and a bombed-out church serving as background to their meeting. Since the rear projection is rather unsteady, however, the artificiality of the scene is foregrounded, thus raising the same question of appearance and reality that is at the center of the partisans' discussion. Furthermore, what General della Rovere openly problematizes is the nature of the self and the reality of identity, and thus serves in an indirect way to extend patterns we have seen operating in Una voce umana and the "Ingrid Bergman" segment of Siamo donne . Just as Magnani's status as actress was foregrounded in Una voce umana , so, too, what we are not allowed to forget here is Vittorio De Sica as actor, playing a role. De Sica, the well-known actor and director, is playing a down-on-his-luck con man named Bertone. Bertone, for increased credibility with the families of the interned men he is trying to help (while helping himself financially) masquerades as a certain Colonel Grimaldi. When he is arrested by the Nazis and made to work for them (significantly, the Nazis want him to discover the identity of a Resistance leader), De Sica/Bertone/Grimaldi steps into his greatest role, that of General della Rovere, which he assumes so completely that he dies. Again, the abîme of representation and the self opens up at our feet as the continuity and certainty of self-identity seem to be threatened. Which is the real man?[15]

These complications reach their peak in the final scene. It would seem that the one thing that can ground this endless play of selves, of appearance and reality, is death. But, in fact, death does not resolve or explain the ongoing displacement, but only halts it, in the most purely functional and banal manner. At the end we are still utterly in the dark concerning Bertone's motives. Some critics have seen his decision to die with the partisans as a decision to end his own rhetoric and the falsity that has defined him since the beginning. It seems equally plausible, however, to view his death as the apotheosis of self-deluding rhetoric, his final histrionic moment, since in terms of the logic of the narrative, he could have told the German officer that he had not been able to discover the true identify of the sought-after leader of the Resistance.

Perhaps most annoyingly to recent Italian commentators, the film is politically ambiguous as well. As in Open City , the Italian Fascists are barely portrayed at all; they parade by in the first few seconds of the film singing their marching song "Camice nere," but this seems to serve more as a historical

marker than anything else. Thus, Italians are again seen only as victims, as when Bertone first encounters the German officer and struggles to find the most ingratiating answers to his questions, rather than the perpetrators they also were. In addition, while generally pleased that Rossellini has softened or even subverted Montanelli's consistent glorification of militaristic and nationalistic values (for example, when Rossellini has Bertone's final courageous resolution spring from the resolve of the others rather than himself), many leftist critics have felt that too many traces of these values remain in the dramatic structure of the film. And it is difficult to disagree. For one thing, the politically progressive figures in the film are portrayed as weak, in need of a strong leader to calm them, like children, during the bombing attacks. Clearly from an aristocratic class, della Rovere is "born to lead," and when he shouts, "Long live Italy!" and "Long live the king!" he unequivocally aligns himself with the military caste. Bertone's change of heart, furthermore, is clearly an ahistorical moral decision rather than one based on a greater understanding of the ideas and ideals of the Resistance, and is related to a certain conflation of religion and the fatherland espoused by Montanelli and his followers. Thus, for Guido Aristarco, perhaps the foremost Communist film theorist in Italy, the film fails because it does not put Bertone's change of heart in a sociohistorical context: if Bertone's idea of the patria were examined critically, Aristarco insists, we might have a better idea why there was such a rush to reestablish the traditional pre-Fascist state after the war.[16] Bertone says he does it out of "duty," but duty is a nonspecific value that can be felt as much by a Fascist as by an anti-Fascist. The ultimate Marxist complaint, then, is that the Fascist past is seen by modern audiences as merely "a moment of human wickedness," in Lino Miccichè's phrase, that all right-thinking men joined to combat: "A prisoner of his Montanellian character, the director made of him a symbol of an anti-Fascist vision which oscillated continually between a vague humanism of the feelings and a cunning and nebulous ethic of 'duty,' almost as if the struggle against fascism had been a question of abstract moral debate rather than a concrete political choice."[17]

This is closely related to the complaint that a new generation of Marxist critics has lodged, not unconvincingly, against Open City and Paisan . Unfortunately, it seems to be the only real link between General della Rovere and the successes of the past, now fifteen years distant.

22—

Era Notte a Roma

(1960)

Era notte a Roma (It Was Night in Rome) has most often been seen as a companion piece to General della Rovere since it, too, looks back to the war years and the Resistance for its subject matter. The films, in fact, do share common themes, attitudes, and formal techniques, but are finally quite different than their chronological proximity would suggest.

Era notte a Roma tells the story of three escaped Allied prisoners—a British captain, an American lieutenant, and a Russian sergeant—who are reluctantly hidden by Esperia, a beautiful black marketeer, while they are in Nazi-occupied Rome seeking to rejoin their lines. (The period is thus the same months of severe deprivation portrayed in Open City , but now seen through the eyes of three outsiders.) The Fascist Tarcisio, a crippled, "spoiled" priest, spies for the Germans; when he tracks down the Allied soldiers' hideout in Esperia's attic, the Russian sergeant and Esperia's boyfriend Renato, a working-class Roman Communist, are killed. Pemberton, the British officer, is subsequently hidden by an aristocratic Roman family and later in a monastery with other escaped Allied prisoners disguised as priests. While trying to help Esperia, he is forced to kill Tarcisio, who wants Esperia to go north with him when the Germans abandon Rome. After their night of suffering ends with the coming of dawn and the American liberation of the city, Pemberton and Esperia are, at the end of the film, too psychologically exhausted and overwhelmed by events to celebrate.[1]

Era notte a Roma is a curious film, not easily domesticated and understood, because it straddles an aesthetic fence. On the one hand, the film is clearly related to the conventional "good" filmmaking that we saw in full operation in

The Resistance revisited: The Russian sergeant (Serge Bondarchuk), the British major

(Leo Genn), the Italian Communist (Renato Salvatori), and the black marketeer Esperia

(Giovanna Ralli) in Era notte a Roma (1960).

General della Rovere . It has a strong plot, dramatic emotion is heightened whenever possible rather than undercut, the music is scored for a full orchestra, and the lighting is professional if unexciting. Yet conventional narrative expectations are not always fulfilled. Thus, when Bradley, the American, decides late in the film to try to get back to the American lines at Anzio on his own, this potentially exciting interlude is casually reported to Pemberton as though it were an offstage death in Greek tragedy. The spots of "dead time" are also less thoroughly pruned here than in General della Rovere . The film seems, in other words, to occupy some uncomfortable position between two aesthetics and often threatens to fulfill neither. The problem for criticism arises when one tries to judge: looked at from the perspective of General della Rovere , it might be said that these moments when "nothing happens" are boring and that the entire film needs to be cut drastically in order to enhance dramatic interest. But if judged from the perspective of Voyage to Italy , say, we can regard Rossellini's longueurs as temps morts that refuse the shortcuts of conventional film grammar and thus begin to move from a smooth realism toward the disjunctive real.

In many ways Era notte a Roma is excellent as a "straight" film, and its depiction of immobility and stasis, the claims of Christian brotherhood, and the desire of all good men to live in peace is convincing and often moving. One

scene, in particular—the touching Christmas dinner in the attic—is especially memorable. The film likewise seems to be a fair portrayal of a particular historical moment: "Jane Scrivener" reports in Inside Rome With the Germans , her detailed diary of the occupation of the city, that it was quite common for Jews, patriots, and escaped prisoners of war to hide in extraterritorial Vatican convents and elsewhere, as Pemberton does, and her diary entry of January 8, 1944, estimates that more than four hundred escaped British prisoners were being hidden in Rome at that time.[2] Other aspects of the film, however, are much less conventional, especially its presentation of character. Thus, the American is "unconvincing" by any normal acting standards, but like "Joe from Jersey" in Paisan , he thereby challenges the film's prevailing realism with the tonic power of the apparently more real. The Englishman delivers his lines so slowly and artificially (in a manner that looks forward to the ponderous, yet effective, deliberation of La Prise de pouvoir par Louis XIV ) that we are continuously prevented from identifying with him emotionally. The Russian remains a mystery to us because he speaks only Russian throughout. In effect, Rossellini refuses to let us get to "know" these men. Similarly, years of indoctrination by Hollywood-style filmmaking lead us to expect that when Esperia and Pemberton get back together again at the end, after her boyfriend Renato's death, some love interest will develop between them. In fact, a ghastly publicity photo reproduced in Renzo Renzi's book on the film shows Leo Genn (Pemberton) and Giovanna Ralli (Esperia) enormously uncomfortable in each other's arms, trying to look amorous. Nothing could be further from the spirit of the film, however, and, defeating conventional expectations, nothing of the sort ever arises. For Rossellini, the depiction of the historical situation is more important than any banal love story. Even more powerfully, most viewers must surely be struck by how hard Pemberton takes Tarcisio's death at the end of the film. The moment is even further underlined by the uncomfortable silence and a restless, wandering camera. In most conventional films, of course, only women are allowed to be horrified after they have killed someone, and it comes as something of a shock to realize just how deeply disturbed Pemberton is. Paradoxically, our shock first registers in terms of a lack of belief, for Pemberton's is an emotion that somehow does not "fit," and thus a sense of "real-life" emotion once again breaks the illusionistic web of realism. What is perhaps most interesting is that, while we see these characters as somehow closer to the real, it is also true that they are stock types. The Russian is impetuous and emotional,[3] the American is practical but whiny, and the Englishman, replete with pipe, is the very embodiment of propriety and good sense. Though many critics have objected to this kind of national stereotyping, our double, contradictory sense of them as types and as unknowable, unpredictable individuals, "real people," actually makes them even more forceful as characters in a film.

This tension between realism and the real is also seen in Rossellini's typical opposition of fiction and documentary, and during the course of the film we see archival footage of the Allied landing at Anzio, the Americans arriving in Rome at the end of the film and, of course, the Germans leaving. Most important is the footage at the very beginning. We learn of the hundreds of Allied soldiers, especially pilots, who were rescued by ordinary Italians at great risk to their

own safety. A voice comes on, speaking American English, with the clear purpose of putting things in context for the film we are about to see, but surprisingly, this neutral, objective, unidentifiable voice suddenly moves into the first person and says, "I'd like to make a statement."[4] Here, perhaps, Rossellini is rehearsing the lesson of India: the only truth is a subjective one, and must always be based in the vagaries of the individual perceiver. In this case, the perception is thematically and formally made relative through its presentation by this unnamed American officer. (During the filming, the director told a reporter for the New York Times that the film would be "an eyewitness testimony . . . as seen by three hiding soldiers.") The voice functions both specifically, as an eyewitness, somebody who asserts and fills the "I" category of grammar, thus motivating the narrative, and generally since, unnamed, it is meant to stand for the entire group of Allied prisoners.[5] And then, brilliantly, Rossellini removes even the grounding of the subjective consciousness, for the speech ends by lavishly praising the "Christian charity" that was everywhere evident and that was the source of these good deeds, and insisting that no one ever acted out of selfish motives. At this moment the film cuts to the three "nuns," in a humorous visual ironization of the voice-over's remarks; we soon see what sharp dealers they are, and how little interested in accepting responsibility for the prisoners, doing so only when it appears they will profit financially.

Another major theme that reappears is that of communication. The languages come at the audience in an alarming and confusing barrage as the characters struggle to understand one another. Early in the film, for example, a comic scene has Pemberton say to Esperia in his faulty Italian, "I want you" instead of "I want tea." The communication theme is also broadened to include the relativity of culture. Thus, when Ivan is ashamed at having chased a live turkey out into the street, thus risking his friends' lives, he wants to leave the attic where they are hiding so that the others will be safe. He warmly embraces them one by one, but since he is speaking only Russian, they have no inkling of his intentions. He then abruptly sits down (which, we learn later, is part of the Russian ritual of leave-taking). Even more moving is the moment during the Christmas dinner in the attic when Ivan, trying to express how much his friends mean to him, begins with a few words of broken Italian, gives up, and speaks passionately in his native language. Neither we nor the others have the faintest idea what he is saying, but the experience is intensely emotional nonetheless. Heavily stressed in terms of the Pancinor zoom technique (which I will discuss in more detail later in this chapter), the moment obviously represents to Rossellini the dream of a full, feeling communication unmediated by the imperfections and false boundaries of diverse human languages. As such, it can be seen as obliquely related to the neorealist dream of the direct presentation of the essence of reality on the screen. This language-subverting outburst works so well, however, precisely because it occurs in the context of, and is defined against, all the other conventional linguistic signification generated in the film.

Other typical Rossellinian themes, such as concealment, imprisonment, and waiting, are continued in Era notte a Roma , but are less narrowly focused on a single strong personality like De Sica's in General della Rovere . Here the narrative is carried by a number of people—which some critics have claimed gives it

a certain undesirable diffuseness, but which also relates it to the decentered coralità of Francesco . Yet Rossellini had already gone too far in his exploration of the individual to be able to reimmerse himself in a simple anonymous group with a mind and will and spirit of its own, and in many ways the film is less choral than simply about a loose collection of individuals who remain individuals.

The theme of appearance versus reality of General della Rovere , especially located around the construction of self and identify, is here, too. Thus, the attic in which most of the action takes place is reached only through a fake cupboard, and the film is preoccupied with disguise and role-playing. Esperia and her fellow black marketeers are first introduced to us as innocent nuns on a foraging expedition among the farms in the Cerveteri region, where they agree to accept the escaped prisoners in exchange for olive oil and some very good prosciutto. This disguise (kept from the spectator as well) leads, back in Esperia's apartment in Rome, to some pleasant comic business when she begins to disrobe in front of the soldiers. Similarly, Pemberton's last disguise is as a priest.

The particular form of these disguises also points up a specific and important connection between Era notte a Roma and Open City , the association of Catholicism and the largely Communist Resistance. Priests like Don Valerio, for example, risk death by hiding Pemberton and the other soldiers in their monastery. Their religious charity, clearly an ongoing value of exceptional importance to the director, hearkens back to the innocent monks of the monastery sequence of Paisan and to the "perfect joy" of Francesco . Most important, it is they who show coralità when, in the second half of the film, the camera zooms slowly back from them at the refectory table (after the news of the German massacre of more than three hundred civilians at the Fosse Ardeatine) from an individual shot to a powerful group shot that suggests a modern recreation of the communality and brotherhood of the Last Supper, the scene represented in the fresco behind them.

Opposed to their goodness stands the corruption represented by Tarcisio, who is short, crippled, and—perhaps worst of all for Rossellini—a spoiled priest.[6] Like the lesbian Ingrid and the sadist Bergmann in Open City , and Enning, the homosexual teacher of Germany, Year Zero , Tarcisio functions emblematically throughout the film. This is true even when he is dead; at the very end, as the approaching dawn brings the American liberators, his lifeless foot sticking out of the door clearly signifies the death of a decadent fascism as well. Even more impressive is the scene in which Tarcisio, having tracked the escaped pilot to the monastery, is able to separate the real priests from those merely masquerading as priests by forcing them to complete a Latin prayer (and thus perverting its purpose). Don Valerio and his fellow priests foil Tarcisio's plan and effect a beautiful, literally choral statement of brotherhood at the same time by beginning to recite the prayer in unison . Tarcisio is shown in a one-shot, appropriately, completely frustrated.

Perhaps the film's closest connection with Open City is the motif of Rome itself. In the earlier film, it will be remembered, the Germans could come in contact with the city only through second-level representations like maps and photographs. In Era notte a Roma , as well, the outsider Pemberton can look

out upon Rome only through the window of his attic prison, as through a frame. Again, the visual shorthand for this motif becomes the dome of Saint Peter's, which is made much of throughout. It is, in fact, as though the director meant to enfold the whole of Open City within the later film, providing it with a significant intertextual resonance that also, of course, is meant to help legitimatize it.

As a marker and reification of history, Rome represents the possibility of a future beyond and without the Nazis, because it so clearly stands for the power and vastness of the past, before the German occupation. The cripple removes all doubt about his depravity when, at the end of the film, he says he longs for all of Rome to be destroyed when the Germans leave. The Latin language operates in similar terms: though Tarcisio temporarily controls the language and uses it for corrupt purposes, the real priests, as we saw, move quickly to reinstitute its historical and spiritual claim. The link with the past is asserted in other places as well: just as in Europa '51 and Voyage to Italy , classical sculpture—which in this film is packed for safekeeping, significantly, in the underground headquarters of the Resistance—states the ongoing presence of a potentially fruitful, if temporarily mislaid, tradition and further legitimatizes the anti-Fascist struggle. (Nor is it an accident that, when we first meet the three escaped soldiers, they are hiding in an ancient Etruscan tomb.) In addition, the unexplained presence of the religious statuary that crowds Esperia's attic and the continuous appearance of bells and churches (as well as the dome of Saint Peter's and the Latin language itself) are clear indications of the central place of the Catholic church in this tradition.

Rossellini's original impetus in making this particular film seems to have been didactic, for he told Renzi that he was concerned about the younger generation's ignorance of fascism. What worried him was the story he had heard about an Italian high school student who, when asked who Mussolini was, guessed that he was a neorealist film director. Yet one would be hard pressed to claim that Era notte a Roma is a historical film in the manner of the films of the last period of the director's career. Nor can it be compared with films like Francesco or even Europa '51; history is taken up here, yes, but the commercial demands for high drama and a strong plot line based on character, however unconventional that character might be, seem finally to work against any truly didactic purpose, at least as Rossellini would later define it.

In terms of technique and mise-en-scène, however, Era notte a Roma is clearly the prototype of the films to come. For one thing, the space before the camera, which the camera creates, now becomes fuller, thicker, more volumetric. To accomplish this, Rossellini returns to the large objects, especially tables, that he had used sporadically to organize and give form to this three-dimensional space. In addition, camera and character have been articulated together on a more equal psychological footing; now that the central female object (or victim) of the camera's gaze is gone, the camera is less obsessively stalking its prey. The sense of pursuit of the earlier films was largely an effect of their emotional distanciation coupled with the tracking camera, physically moving its way through space, and the particularly pressing psychological resonance that can accom-