Down the Drain: Numismatics as Art

. . . sooner find the Prosodia in a Comb as Poetry in a Medal.

—Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

Among Duchamp's last ready-mades, we find two works, Drain Stopper (fig. 64) and Marcel Duchamp Art Medal (fig. 65), which bring us back full circle to Fountain , while simultaneously raising questions about value and its relation to art and monetary tokens. Drain Stopper is an item of hardware that Duchamp recycles from his bathroom in Spain, modified by being thickened with additional lead. Marcel Duchamp Art Medal is a cast from Drain Stopper in several versions, including bronze, steel, and silver editions, issued by the International Numismatic Agency (also known as the International Collectors Society, New York.[47] William Camfield considers Drain Stopper as a companion piece to Fountain , Morton Schamberg (1881–1918) and Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven's (1874–1927) God (circa 1918), and a part of Duchamp's "conceptual plumbing system."[48] Although plumbing and various items of hardware feature prominently in Duchamp's works, functioning as backhanded jokes on the sanctity of art, the reissue of the drain stopper as an art medal demands that the question of value in the context of mechanical and artistic reproduction be addressed once again. The invocation of plumbing in this "artistic" context becomes the literal conduit for examining how value is generated and expended, both as abstract property and as precise currency. The transformation of a drain stopper (thickened with lead) into art, and its reproductions, or rather transmutations, into coins and/or medals, attest to the expandable liquidity of art as a symbolic currency.

Duchamp's sole "rectification" of the Drain Stopper is to have thick-

ened it by adding more lead. This intervention may not seem to amount to much, particularly in terms of accounting for the recuperation of this object as a work of art. If we consider the gesture of adding lead as a pun, however, it seems that this object takes on new proportions. By thickening the drain stopper, Duchamp literally adds more weight to it, and figuratively suggests that he is now dealing with weighty matters. At first sight a joke, the Drain Stopper now emerges as an object whose literal gravity attests to its potential seriousness as a work of art. But is Drain Stopper a work of art? Duchamp's gratuitous gesture of choosing the drain stopper converts it into a work of art at the same time that it destroys the notion of the drain stopper as an art object. Thus, like Fountain, Drain Stopper is only provisionally a work of art; it is more like a stopper—a stop-gap measure or makeshift substitute (a pun on bouche-trou , its French title)—or a punctuation mark (indicating a pause or delay), rather than an actual art object. Poised between the wet (an allusion to painting as a purely material art "the splashing of paint") and the dry (a conceptual interpretation of art that includes mechanical reproduction), Drain Stopper acts like

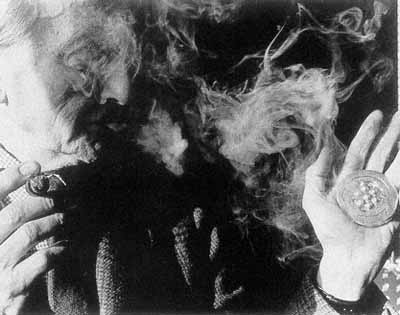

Fig. 65.

International Collectors Society sales brochure cover, 1967. Shows Duchamp with

cigar smoke holding Marcel Duchamp Art Medal, which is based on Drain Stopper.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Fig. 66.

Leon Battista Alberti, Medallion, self-portrait, 1438.

From George Francis Hill, A Corpus of Italian Medals

of the Renaissance before Cellini Firenze: Studio per

edizioni scelte, 1984. Courtesy of The British Museum.

a regulative device controlling the transition between art and nonart. Like a pun, "stopper"—which means to regulate sound (as pitch in music) or light (as a photographic aperture)—mechanically triggers both the linguistic and the visual registers.

But "stopper" also has another meaning, that of securing one's chances in bridge (a stopper is a card that will ultimately take the trick in that suit). This latter pun inscribes the Drain Stopper into a gamble, which in the context of Duchamp's works is invariably a gamble on art. This gamble is explicitly played out in the transformation of Drain Stopper into Marcel Duchamp Art Medal , that is, from a ready-made into a mold for a series of artistic medals and/or numismatic coins. Duchamp's issue of an art medal (also known as Metallic Art ) would seem to be contrary to his iconoclastic position as an artist, particularly one who refuses to be identified as such. The fact that this art medal is also a numismatic coin, however, reminds the viewer of the coincidence of economic and artistic concerns, insofar as they embody ancient modes of mechanical reproduction, those of Greek founding and stamping.[49] Duchamp's Art Medal or Metallic Art is a Janus-faced representation of two opposing traditions.

The first is the commemorative tradition of the art medal, particularly popular during the Renaissance, which singles out the deeds or actions of an individual by immortalizing those actions through a motto and emblematic insignia. The second refers to the economic and symbolic value of coinage as an archaic measure and standard of exchange.

What then is the function of Marcel Duchamp Art Medal , as both a commemorative medal and a numismatic coin? As a commemorative medal, Marcel Duchamp Art Medal can be said to celebrate the emergence of a new type of art object: Fountain, the ready-made that literally flushed the traditional concept of art down the drain. Given Duchamp's concern that "Men are mortal, pictures too" (DMD , 67) and that "The onlookers make the picture," the effort to commemorate either the work of art or the artist takes on a "tongue and cheek" dimension. Duchamp's challenge of the commemorative aspects of art and its equation with the "rictus" of death is explicitly staged in his ironic self-portrait with my tongue in my cheek (fig. 46, p. 115).[50] This work celebrates Duchamp's specific contribution to art, his refusal to hold his "tongue in check," like other artists. Could this "tongue and cheek" work be considered as a belated commentary on the artistic medals of the Renaissance?

If we briefly consider the similarities between Duchamp's with my tongue in my cheek, Leon Battista Alberti's Medallion, Self-Portrait (1438) (fig. 66), and Matteo de' Pasti's Medal of L. B. Alberti (1448) (fig. 67), some surprising conclusions emerge. Alberti's medallion includes a profile self-portrait with a winged eye under the chin. De' Pasti's medal divides

Fig. 67.

Matteo de' Pasti, Medal of L. B. Alberti, 1448. From George Francis Hill, A Corpus of

Italian Medals of the Renaissance Before Cellini. Firenze: Studio per edizioni scelte, 1984.

Courtesy of The British Museum.

these elements, by separating Albert's profile and name on one side of the medal, while the reverse side depicts the winged eye surrounded by laurel wreaths, with the inscription Quid Tum.[51] The visual message of both Albert's medallion and de' Pasti's medal affirms the affinity of artistic conception with divine omniscience and glory. This visual message, however, is undermined on de' Pasti's medal by Cicero's motto "Quid Tum" ("What Then?"), which is believed to be a query on that which follows death.[52] Given Duchamp's critique of the artist as master of the visual, or "retinal euphoria," could it be that the winged eye under Alberti's chin may reappear transposed as Duchamp's swollen cheek, as the "tongue and cheek" signature of the artist as metaironist?

Now we may begin to understand Duchamp's interest in artistic medals, and in numismatics in general. The artistic medal, like the numismatic coin, is an archaic ready-made, whose double-faced (punning) visual and scriptural character captures the ironic nature of art: that artistic glory is not assured but on credit—conditional on the judgment of the spectator. The effort to commemorate the artist or the work, through medals or tokens, relies on the posthumous judgment of the spectator. This is why, according to Duchamp, "Posterity is a form of the spectator." Thus the commemorative gesture is merely a gamble whose interest lies in the hands of the future.

As a numismatic coin, Marcel Duchamp Art Medal immortalizes artistic glory by transforming it into coinage (commonplace, koinon , in Greek), that is a token of exchange. This medal/coin, however, no longer refers to the artist in a historical sense but rather to the history of the medium, since coins are the ready-mades of antiquity. The reproducible character of numismatic coins alludes to the origins of technology, the traditions of founding and stamping that precede the advent of the print medium and modern modes of mechanical reproduction by thousands of years. Coins are among the earliest artifacts of history; they are the first publications or impressions, whose characters give voice to history.[53] According to John Evelyn, coins are "vocal Monuments of Antiquity," the first and most lasting material traces of history.[54] Like the ready-mades, ancient coins embody contradiction, since they are simultaneously a material commodity (exchanged by virtue of material weight, for example, an ingot), and abstract currency (as medium and measure of exchange). Marc

Shell attributes this distinction between substantial value (material currency) and face value (intellectual currency) to the development of the polis.[55] The inscriptions on ancient coins attest to the transformation of the concept of value from value based on weight, to value based on political authority, that is, forms of legitimacy defined through symbolic exchange.

This tension between the coin as material and symbolic currency is compounded by a further ambiguity, that of the apparent contradiction of the coin as an artistic and as an economic object. This confusion is tied to the effects of inscription, be it verbal or visual, that conceptually transform a piece of metal into both an aesthetic and economic artifact. As Marc Shell observes: "The pictorial or verbal impression in this material qualitatively changes it (aesthetically) from a shapeless piece of metal into a sculptured ingot and, more significantly, qualitatively changes it (economically) from a mere commodity into a coin or token of money."[56] The minting of coins generates qualitative changes that transform the coin into both an aesthetic and economic object—domains that are considered to be mutually exclusive today. This coincidence of material and symbolic properties, as well as the processes of artistic reproduction and economic production, reveal Duchamp's interest in numismatic coins. Not only is a coin an archaic ready-made but it is also a pun, to the extent that its double-faced (Janus-like) character functions not as an object but as a mechanism that stages a new way of conceiving modernity. Marcel Duchamp's Art Medal numismatic coin suggests that mechanical reproduction, believed to define the origins of modern art, is present in antiquity before the emergence of the artistic as an autonomous domain. At issue is not the effort to de-historicize modernity by denying the preeminence of mechanical reproduction as its defining idiom, but rather to recognize the presence and social impact of its archaic manifestations. Instead of identifying mechanical reproductions as a purely technological intervention, Duchamp discovers in its socially symbolic character a conceptual potential, thereby demonstrating the intellectual overlap or punning relation of artistic and economic modes of production. In what is literally a "mirrorical return" on the opposition of art and economics, his Drain Stopper and Marcel Duchamp Art Medal suggest that coins are the "first" ready-mades, and that his own ready-mades are a mere extension and rectification of this tradition. By insisting on the conceptual dimension of

numismatics, Duchamp delays its economic impact, only to recover its intellectual impact. In doing so, Duchamp restores to the viewer a purely speculative concept of artistic production, which can only be thought through the expenditure of the terms that define economic production.

Duchamp's works challenge classical notions of value, by radically redefining both artistic reproduction and economic production through a revalorization of the intellectual potential of mechanical reproduction. This study has demonstrated that the concept of reproduction in Duchamp's works involves a new way of thinking about art. By exploring the "infrathin" interval separating an original from its copy, Duchamp is able to overcome the opposition between art and nonart. Taking mechanical reproduction as a given, Duchamp redefines the "object" as a set of impressions, like imprints drawn off the same template. Rather than considering the art object as unique, Duchamp redefines it as multiples, ready-mades that are like a limited edition of prints or coins, whose artistic value, like that of money, is negotiated by limited editions. In a photographic print of Duchamp's ready-mades in his studio (taken by Man Ray in 1920) there is a type chart from a French printing firm that serves to remind us of the significance of printing to our understanding of his work:

Printing is not such a recent invention as it is usually believed. Block printing had been used in China for more than sixteen hundred years; the Greeks and the Romans were familiar with movable stamps or types; the picture books that appeared in the early fifteenth century served as models for the experiments made by Gutenberg in Mainz in 1450 with wooden types.[57]

The history of printing and its affinity to techniques for founding and stamping marks the convergence of the artistic and the economic domains. By revalorizing printing as a medium that involves a conceptual potential, Duchamp does away with the opposition between the artist and the printer, between fine art and artisanal technique. This attempt to challenge the boundaries of art and technology explains his preference to define art as "making," and the artist as "craftsman" or "art-worker" (DMD , 16, 20).

Quaintly labeled by Robert Smithson as the "spiritualist of Woolworth," because of his relic-like, almost "spiritual" pursuit of the commonplace, Marcel Duchamp extends through his works the most radical critique of the notion of artistic value.[58] Foregoing both sentimentality and idealization, Duchamp explores how the notion of mechanical reproduction, based on principles of economic production and expenditure, alters the concept of artistic production. As this chapter has shown, however, Duchamp's appeal to and use of economic notions, such as commercial transactions and monetary tokens, is speculative rather than empirical. His interest in economics is conceptual involving an understanding of the mechanisms involved in the generation and expenditure of value. Duchamp is not concerned with the recovery of value in the classical economic sense but rather, in its expendability, for his works attest to the redefinition of notions of both artistic and economic production through the deliberate exploration of the notion of economic and artistic reproduction. Just as the ready-made challenges the autonomy of a work of art, not by postulating new value but instead by embodying its expenditure as "criticism in action," so does Duchamp's invocation of economic categories function as a way of challenging artistic categories. The result involves the subversion of art through the elaboration of an unartistic concept of art (nonart), leading to a critique of value as social and economic reality through its speculative expenditure.

According to Robert Lebel, Duchamp "derived his most obvious satisfaction from the very modesty of his profits." Duchamp's enjoyment in minimal economic returns corresponds to his efforts to maximize speculative "profits." It reflects Duchamp's artistic strategy as the master of "tongue and cheek" humor. Commenting on Duchamp's humor, Lebel suggests that its logic is more in the order of expenditure, than a rational economy based on interest:

If at all costs a rule must be discerned in Duchamp's humour, we think this is it: that it has to have a concrete result—consequently his humour is never gratuitous—but the flagrant disproportion between effort and result proclaims—with hidden noise—this result as the collapse, or better yet, the preposterousness, of a technocracy paralyzed by the very excess of its own efficiency.[59]

This disproportion between efforts and result in Duchamp's humour corresponds to the strategies of delay that Duchamp deploys in the economic domain in order to challenge the notion of value in the artistic domain. The invocation of a technocracy and even bureaucracy serves to undermine through the expenditure of efficiency the economic and artistic rationale of modernity. Like his father, who was a notary, and his symbolic father, François Villon, who celebrated his poetic legacy in his Testament , Duchamp commemorates his own artistic legacy as a stop-gap measure, a ready-made drain stopper that is also an art medal. Poised between an art that has lost its physical bite, and another, which can bite only because it is no longer art, Duchamp's stop-gap measure emerges as both predicament and testament. As the notary of modernity, Duchamp writes its most tortuous and deliberate "will," one whose language continues to this day to be "killingly funny."