17—

Ou-yang Hsiu (1007–1072)

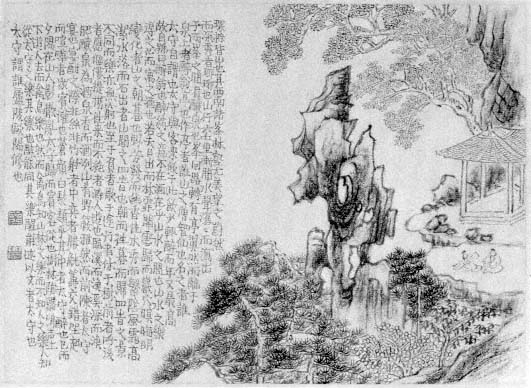

Fig. 23.

Chin Nung (1687–1773), "The Pavilion of the Old Drunkard" by Ou-yang Hsiu . Leaf F of

Album of Landscapes Illustrating Poems and Essays By Famous Writers (1736), Museum

Rietberg, Zürich, Gift of Charles A. Drenowatz. Ou-yang Hsiu is depicted here sitting with

a companion by the pavilion with his travel account fully inscribed as a colophon.

Ou-yang Hsiu was one of the dominant figures of Northern Sting literature and politics, a leader of a circle of literary progressives who consolidated the ideals of the Ancient Style. Later canonized as one of the Eight Masters of T'ang and Sung Prose, he was a prolific writer in a variety of prose and poetic genres. Born in Yung-feng, Chi Prefecture (modern Chi-shui, Chiang-hsi), Ou-yang entered the Imperial University after twice failing the prefectural examinations and, in 1030, distinguished himself by placing fourteenth in the palace examinations. In 1036, he was exiled and demoted for supporting Fan Chung-yen's criticisms; he was recalled in 1040 along with Fan and rose to become a drafting official because of his fame as a writer. Fan and his faction again fell from power in 1045. The following year, Ouyang's reputation was damaged by a scandal in which he was falsely charged with incest and imprisoned; his known fondness for singers and writing romantic poetry may have made him particularly vulnerable to such charges. After his acquittal, he was once again exiled and made prefect of Ch'u Prefecture (modern Ch'u District, An-hui), where he wrote The Pavilion of the Old Drunkard , one of his most enduring works. Ou-yang Hsiu subsequently served as prefect of Yang-chou, where he revived his romantic reputation, as well as prefect of Ying Prefecture (modern Fu-yang, An-hui), a scenic area where he later retired. He returned to the capital in 1054 and became increasingly influential in the central government, rising to the powerful position of assistant chief minister. During the following period of thirteen years he served as co-editor of The New History of the T'ang Dynasty (Hsin T'ang shu , 1060) and single-handedly wrote The New History of the Five Dynasties (Hsin Wu-tai shih , posthumously

published in 1072) as models of the Ancient Style; both works were praised by literary stylists but later criticized by historians. He further consolidated the position of the Ancient Style when, as chief examiner in 1057, he required it in examination essays and failed those who wrote in other styles. It was through this examination that he discovered Su Shih and Su Ch'e, destined to become leading literary figures of the next generation. Ou-yang Hsiu served in various highlevel positions during the 1060s, and his administration was noted for its stability and several progressive reforms. However, he was again falsely accused of incest, though again cleared. He repeatedly requested assignments away from the capital and finally, in 1071, was allowed to retire with the title of Junior Preceptor of the Heir Apparent.

Ou-yang Hsiu left over five hundred pieces of prose in a variety of forms, all characterized by a tight sense of structure. He was also an early proponent of the miscellany (pi-chi ), producing several influential collections as well as an early travel diary, Diary of My Route to Assume Office (Yü-i chih ), written while journeying to a new post to which he was demoted in 1036. In The Pavilion of the Old Drunkard , the presence of parallelistic elements and syntactical repetitions create a sense of playfulness and humor reflecting the informality of the piece. Ou-yang was relatively unconcerned with the metaphysics of Nature or speculative philosophy; this piece reveals instead his pragmatic interest in concrete human activity and in the texture of the observable world. Its cumulative effect is to convey Ou-yang Hsiu's undiminished humanity and commitment while an official in exile.

The Pavilion of the Old Drunkard (Tsui-weng-t'ing) is located on Lang-ya Mountain in the southwest of modern Ch'u District, An-hui, about two miles from the city. It was ordered built by Ou-yang Hsiu himself, who had the monk Chih-hsien supervise its construction on a scenic spot next to a spring. The elegant open building has been restored many times, and the area abounds in inscriptions dating back to the T'ang and Sung. Ou-yang's original calligraphy of the text was engraved at the site in 1048 but proved unsuitable for making rubbings. In 1091, Su Shih was asked to rewrite the text in larger characters, and this engraving was widely reproduced.

The Pavilion of the Old Drunkard  (1046)

(1046)

Mountains ring the seat of Ch'u Prefecture.[1] The many peaks on the southwest are especially beautiful, with their forests and valleys. I

gazed into the distance at one that was luxuriant, deep, and graceful—Lang-ya Mountain.[2] I walked more than two miles up the mountain and gradually heard the gurgling sound of water, "ch'an-ch'an ," until I found, splashing out from between two peaks—Fermentation Spring. The peaks circled around me as the road twisted and turned until there was a pavilion with eaves like wings, facing the spring—the Pavilion of the Old Drunkard. Who built this pavilion? A monk on the mountain—Chih-hsien. Who named this pavilion? The Prefect did, after himself. For the Prefect comes here to drink with his guests. After drinking only a bit, he quickly becomes drunk, and because he is the oldest, he calls himself "the Old Drunkard." But wine is not uppermost in the Old Drunkard's mind. What he cares about is to be amid mountains and streams. The joy of the landscape has been captured in his heart, and wine drinking merely expresses this.

When the sun appears, the mist disperses through the forest; when clouds return to the mountains, the caves in the cliffs darken. These transformations from brightness to darkness—such is dawn and dusk on the mountain. When wildflowers blossom giving off subtle fragrances, when fine trees flourish providing extensive shade, when the wind is clean and the frost is pure, when the water is low and the rocks become visible—such are the four seasons in these mountains. If one comes here in the morning and returns in the evening, one will notice the scenes differing throughout the four seasons and experience a joy that is likewise inexhaustible.

Men bearing loads sing along the road, while travelers rest under the trees. Those in front call out; those behind respond. The elderly, hunched over ones leading the young by the hand as they come and go ceaselessly—these are the people of Ch'u on their outings. Along the stream they fish: the stream is deep, the fish, stout; they ferment the spring water into wine: the water is sweet, the wine, clear. Various kinds of mountain game and wild vegetables casually served—such is the Prefect's banquet. The gaiety of the feasting and drinking is unaccompanied by strings or flutes. Someone wins at tossing arrows into a pot; another gains victory at chess. Winecups and wine tallies crisscross back and forth. Shouting out as they jump up or sit down—such is the happiness of all the guests. And the person with the aged face and whitened hair who sits slumped among them—the Prefect, drunk.

Before long, the sun sets behind the mountain; the people along with their shadows disperse. The Prefect returns, followed by his guests. As the forest covers everything in darkness, cries ring out all over—such is the joy of the birds as the visitors depart. The birds can

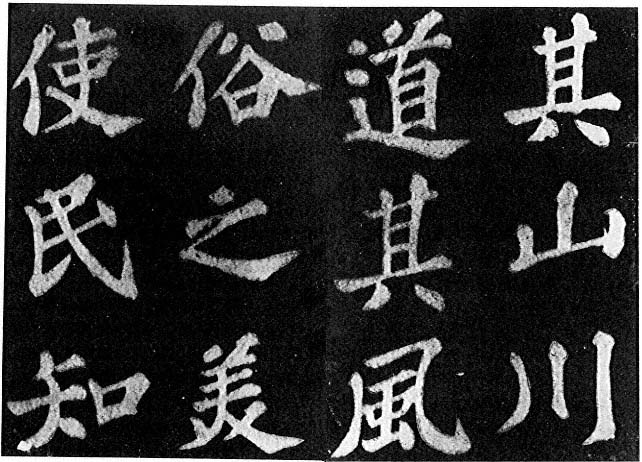

Fig. 24.

Rubbing of Su Shih's Inscription of The Pavilion of Joyful Abundance

(detail, original ca. 1091). From Su Shih, Feng-le-t'ing chi (rpt. Taipei, 1975).

only enjoy the mountains and forests: they cannot understand the joy of people. The people can only enjoy this outing along with the Prefect: they cannot understand that the Prefect was enjoying their joy. He who, when drunk, was able to share their joy and, when sober, could describe it with literary flourish is—the Prefect. And who is this Prefect? Ou-yang Hsiu of Lu-ling.[3]

The Pavilion of Joyful Abundance  (1046)

(1046)

This piece was also written while Ou-yang Hsiu was exiled in Ch'u Prefecture. In contrast to the casual attitude of The Pavilion of the Old Drunkard , this is a more decorous composition meant to be publicly displayed as an explanation of the moral significance of the pavilion's name. It displays a historical sense of place, as well as loyal political sentiments. Ou-yang Hsiu contrasts the past, a long phase of disorder

and suffering, with the present state of peace and prosperity in which he implicitly participates. The theme of joyful abundance enables him to offer praise to the dynasty that was punishing him for his views and to articulate the Confucian virtues that would merit his recall to the capital. The pavilion at the foot of Mount Abundance (Feng-shan) near Lang-ya Mountain was also ordered built by Ou-yang Hsiu in 1046 in order to celebrate the bountiful era. Standing beside a spring surrounded by a tall peak and bamboo-covered hills, it became a frequent destination for his excursions. The text was also rewritten by Su Shih and engraved at the site.

Only in the summer of the second year after I took office in Ch'u Prefecture was I able to taste the spring water hereabouts and discover its sweetness. When I asked a local person about it, I found that it had come from the south of the prefectural city, no more than a hundred paces away. Above it stood Abundance Mountain,[1] lofty and strikingly erect; below it was a secluded valley, remote and shady, and hidden deep. Between them was a pure spring overflowing and spurting upward. I gazed up and peered down to the left and right, and was delighted at what I observed. So I cut through the rocks to make a path for the spring, and cleared some land for a pavilion so that I could make excursions here along with the people of Ch'u.

Ch'u was a battlefield during the wars of the Five Dynasties. Formerly, Emperor T'ai-tsu of the Sung[2] led the army of the Latter Chou to defeat the 150,000 troops of Li Ching at the foot of Pure Stream Mountain.[3] He took prisoner Generals Huang-fu Hui and Yao Feng outside the East Gate of the city of Ch'u Prefecture, finally pacifying Ch'u.[4] I investigated the terrain, consulted maps and records, climbed up high to observe Pure Stream Pass, and sought to find the place where Huang-fu Hui and Yao Feng were captured. But there were no living survivors, for it has been a long time since peace was established through the empire.

After the T'ang dynasty lost control, the entire land split apart. Strongmen arose and fought each other. Were not those warring kingdoms beyond counting? Then, when the Sung received the Mandate of Heaven, a sage arose and unified all within the four seas.[5] The strategic bases of those contenders have been demolished and leveled. A century later, all is peaceful: nothing remains except the tall mountains and pure streams. I wanted to inquire about these events, but the survivors are

all gone now. Nowadays, Ch'u Prefecture is located between the Long and Huai rivers, yet merchants and travelers do not come here. The people are unaware of events outside and are content with farming and providing clothing and food so that they are happy in life and provided for in death. But who among them realizes that it is the achievements and virtue of Our Sovereign which has allowed them to thrive and prosper, flourishing for as long as a century?

When I came here, I was delighted by the isolation of the place and the simplicity of official business. I was especially fond of the relaxed way of life. So, ever since discovering this spring in a mountain valley, I have come here daily together with the people of Ch'u to look upward and gaze at the mountain and to peer down to listen to the spring. I gather hidden flowers and seek shade under the lofty trees. I have visited it in wind, frost, ice, and snow, when its pure beauty is revealed. The scenery during the four seasons is always charming. Moreover, it is fortunate that the people are joyful over the abundant harvests and are happy to travel here together with me. I have used this landscape to praise the excellence of their customs so as to remind the people that they can rest content in the joy of this year's abundant harvest, because they are fortunate enough to live during a time free from trouble.

To proclaim the benevolence and virtue of Our Sovereign and share the joy of the people is the duty of a prefect. Thus, I have written this account and named the pavilion after this.

WRITTEN BY OU-YANG HSIU, EXHORTER ON THE RIGHT, PROCLAMATION

DRAFTER, AND PREFECT OF CH'U AND CHüN PREFECTURES, IN THE SIXTH MONTH

OF THE YEAR PING-HSÜ DURING THE CH'ING-LI ERA [JULY—AUGUST 1046][6]