Mexican Rock's Reception

With the heightened commercialization of La Onda came a deepening of its class makeup and a diversification of its audience along gender lines. In this respect, it demonstrated that mass culture was a powerful organizing tool that transcended class boundaries; rock was inclusionary.[91] The broadening appeal of rock coincided with a relaxation of restrictions on native concert performances as part of Echeverría's outreach to youth. More women joined the counterculture as well, influenced by the rising feminist discourse against machismo and the discovery in La Onda of new participatory spaces freed of the conservative social strictures of family and state. In a fundamental sense La Onda was proving itself capable of transcending class and gender boundaries to incorporate a diversified audience bound together by shared reference points in music, speech, and dress. Yet if this was the ideal, there were also important class and gender contradictions that defined this imagined community.

An indication of the underlying conflicts that characterized the interclass nature of La Onda can be gleaned from a concert review of an outdoor

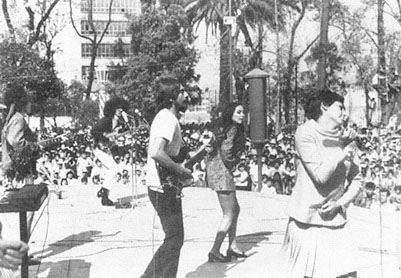

Figure 14.

Javier Batiz performs in the Alameda Park in Mexico City, c. 1971.

Source: Federico Arana, Guaraches de ante azul: Historia del rock mexicano

(Mexico City: Posada, 1985), vol. 3, 146. (Reproduced courtesy of Federico Arana)

festival that took place in Chapultepec Park—a gigantic public park in Mexico City known for its diverse class attendance—in the spring of 1971. Interestingly, the concert was organized as part of a government program to provide free Sunday entertainment, "or the official effort to get close to rock," as one reviewer cynically put it.[92] Indeed, other outdoor rock concerts were officially sanctioned under the apertura democrática (see Figure 14). Polydor threw its support behind the Chapultepec festival by offering a prize of 6,000 pesos (around U.S. $500), instruments, and a recording contract to the best band. The festival, however, turned tense when the audience, composed in large part of lower-class youth, created "an atmosphere of chiflidos [a loud whistling used to convey disapproval] and naranjazos [literally, throwing oranges]," apparently in response to the mediocre quality of the music. A woman, "good looking (but a bimbo)" and associated with the festival came on stage to try and calm down the crowd. But her false posture of hipness "contradicted the cultural intent of the event" (that is, an authentic countercultural gathering), in the words of the reviewer, and unleashed a torrent of derision and laughter from the crowd.[93] While the reviewer (a male) harshly criticized the woman's superficial understanding of La Onda, both the female stage announcer and

the male reviewer revealed a fundamental misunderstanding of the audience's reaction. By seeing the chiflidos and naranjazos as an inappropriate response to rock—"modern music [that] is incomprehensible by the popular majority"[94] —the reviewer unwittingly revealed his own elitism, and a deeper appreciation of rock's relatedness to barrio culture was lost. If the middle and upper classes assumed that rock was meant to be revered, the aggressiveness reflected in the response of the festival's audience reflected the alternative perspective that, for the lower classes, their voice was to be heard as well.

For the lower classes, rock was (and continues to be) not just about listening but also, and fundamentally, about participating in the musical space organized by live performance. The opportunity to participate was provided especially by the hoyos fonquis, which introduced a reorganization of urban social space by situating rock performance as an inextricable aspect of barrio life. As Joaquín López recalled, "With the hoyos fonquis we're talking about a marginalized barrio made up of marginalized people who are attending these rock events. Not so much to dance—these weren't dances, exactly. They were more like auditions.... Sure, people danced, but you didn't get the feeling it was like a formal dance hall, you know? But rather, a mass concert."[95] Unlike the more regulated concert spaces, such as those at the National Auditorium and private music clubs, the hoyos fonquis were open-ended performance spaces that allowed for—indeed, endorsed—the kind of aggressive give and take central to rock's appreciation by the lower classes. The concert in Chapultepec Park seemed to mirror the conditions of the hoyos fonquis in terms of audience and also in the breakdown of respect for the performers and organizers.

Addressing the latent class tensions that were building, the reviewer described how the woman exacerbated an already tense situation by "communicating in jipi slang," whereas much of the audience "uses such slang in a more authentic way." She could not transcend her own class position simply by appealing to the language of the youth culture. This recalls earlier comments by Manuel Ruiz that the juniors used the vehicle of La Onda as a way to be seen as "with it," but this often came across as forced and artificial. The class conflict experienced along cultural lines at the festival led to "small outbreaks of violence, objects thrown through the air, and a generalized tension."[96] For the reviewer, the concert's disastrous outcome pointed to the "deficiencies" of rock's "projection and diffusion" in Mexico: "One can begin with the fact that the audience ... [is] in its majority made up of people who don't understand rock for obvious reasons of customs, a culture deeply rooted in folklore, and the lack of appreciation for any mod-

ern expression with artistic intention.... Being fair about it, the Mexican masses are not yet ready for a rock festival, which doesn't mean they're not ready for rock."[97] What was really at stake, however, was not whether or not the "masses" were "ready" for rock; the assumption of rock as high culture reflected the obvious biases of middle-class critics. Rather, the criticism (repeated on other occasions) pointed to profound cultural differences between the classes in their consumption patterns and thus in the usage of rock music in their lives.

For the middle and upper classes, rock music offered a vehicle for rebellion, but one closely patterned on the ideal of the U.S. model. The relationship between audience and performer was interactive yet clearly bounded. For the lower classes, on the other hand, rock provided a vehicle for mass participation and the spatial reorganization of everyday life. Performers had to gain the respect of their audience precisely by breaking down the imaginary boundaries that kept the two apart. As Víctor Roura would later comment about the hoyos fonquis, "It's curious, but in order for a group to be respected it has to show a lack of respect."[98] Rock offered a fundamental shift in perspective and way of being, a shift marked by the possibility of participation and the articulation of needs. As Ramón García eloquently expressed it:

I think that [rock] is about the support for reaffirming who you are. I believe that rock was born from restlessness in order to reaffirm that restlessness. Being from a country like Mexico, you can't keep from noticing so many things, so much injustice and all that. So if rock gave you some support or something that made you feel better.... I think that definitely rock is an essence, a way of life. It's a form of life. It's not about the moment, a momentary euphoria. It's a way of life, and as such its rhythm helps you to reaffirm who you are.[99]

These class-based values were not in fundamental conflict. Rock served as a common denominator for youth generally. However, because rock had different meanings according to one's class position, the ideal of a rock community was fundamentally flawed. Mass culture might indeed transcend class, but it does so neither uniformly nor with predictable outcomes.