SOUTH OF SANTA FE

Pecos Pueblo:

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles de Porciúncula

1598?; after 1629; c. 1696; c. 1717

In 1838 the last dejected inhabitants of Pecos pueblo left their homeland forever. This remnant of a once-thriving community sought asylum with their linguistically related kin at Jemez. As a last act of devotion they deposited the sacred image of San Antonio that had graced the wall of their church with the European town nearby, instructing the new caretakers to maintain the image with appropriate care and dignity. (Each year a festival would renew the contract between the Pecos survivors and their patron saint.) So closed a long and full chapter in the history of New Mexico Indian and Hispanic relations.

A rare exception to the hundreds of miles of arid plains lying east of the Rio Grande was the Pecos River drainage. As the last outpost, the hinge between settlement and desolation, the river had supported habitation in the form of a series of Indian pueblos and later European settlements. The largest among them was the thriving Pecos cluster, which at the time of the Spanish contact was estimated at a population of about two thousand souls. During the Archaic Period (from 5500 B.C . to A.D . 700–800) the settlement was characterized by a small population living in pit houses but already engaged in agriculture.[1] After the year 900, however, no record remains of inhabitation for the next two to four centuries. Typically the architecture developed from partially subterranean to fully aboveground structures, first built in a puddled mud technique but by 1300 constructed almost entirely of sandstone from the vicinity. All the villages except Cicuye were abandoned by 1450, its population concentrated in structures stacked up to five stories in height.[2]

The village's position on the edge of Pueblo culture guaranteed an intermediary role to Pecos, in which they traded cotton stuffs, pottery, belts, and food for buffalo products, beads, and leatherwork. In time the Pecos Indians also served as the intermediary between the Plains Indians and the Spanish, as did Taos to the north and Gran Quivira to the south. As usual, the recorded story begins with Coronado's party, which moving eastward in search of riches reached Pecos in May 1540. The Spanish camped there in late April or early May on their way east to the "country of the cows" (buffalo).[3]

Coronado's chronicler, Pedro de Casteñeda, noted the configuration of the pueblo: "Cicuye is a pueblo of nearly 500 warriors, who are feared throughout the country. It is square, situated with a large court or yard in the middle containing the estufas. The houses are all alike, four stories high. . . . The village is enclosed by a low wall of stone."[4] The setting was superb: a low ridge within the valley allowed

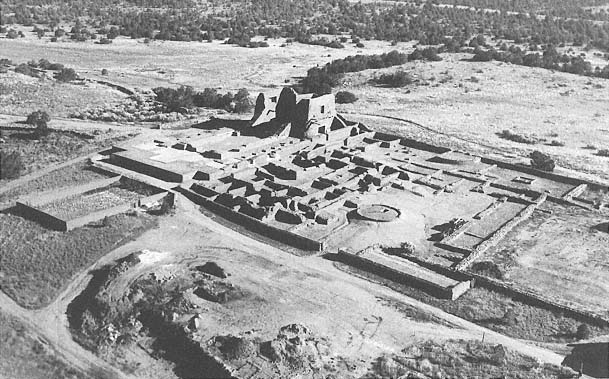

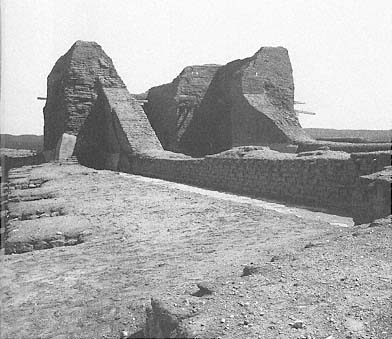

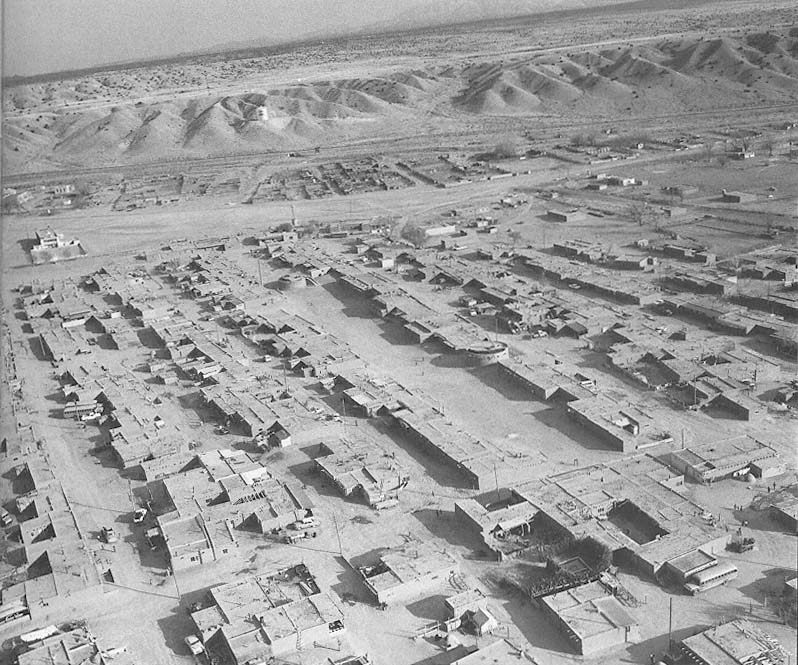

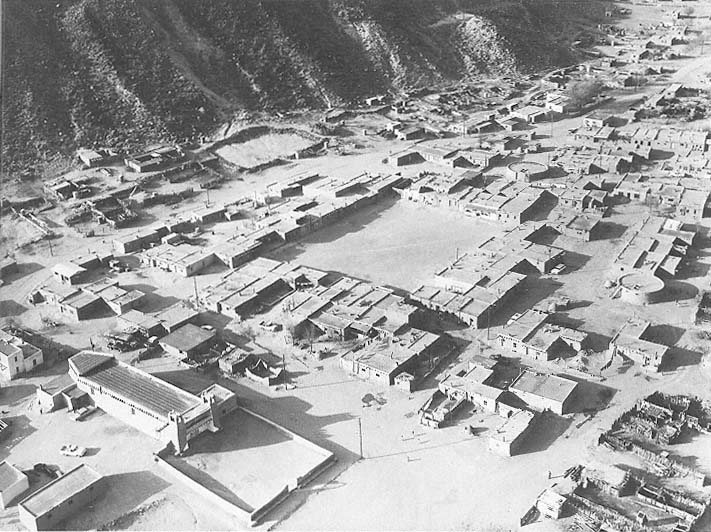

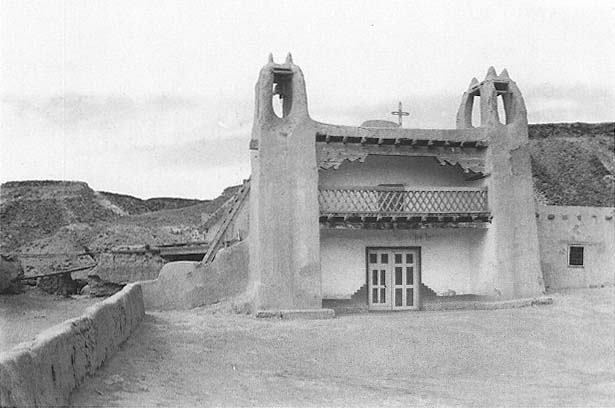

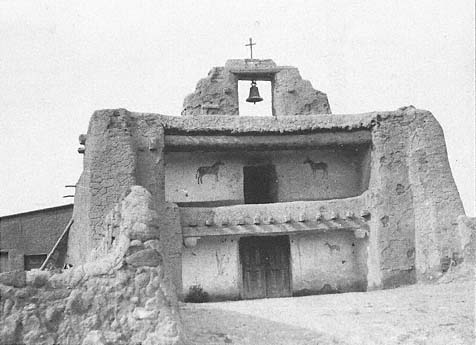

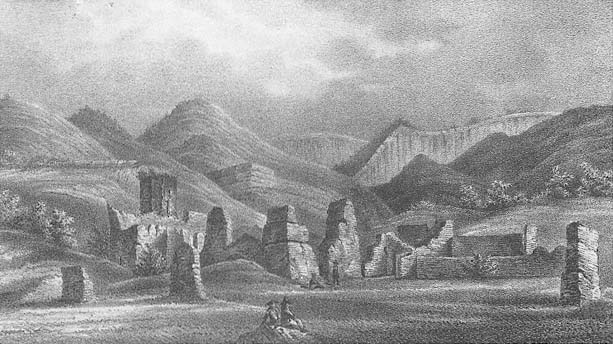

17–1

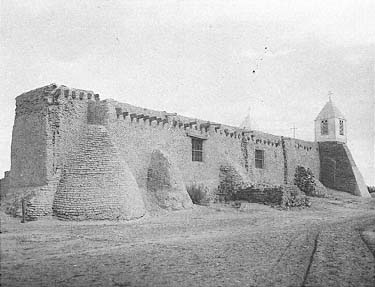

Pecos

Mission and pueblo ruins from the southwest.

[Fred Mang, Jr., National Park Service, no date]

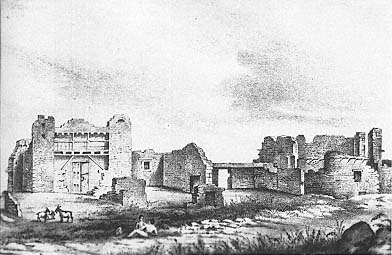

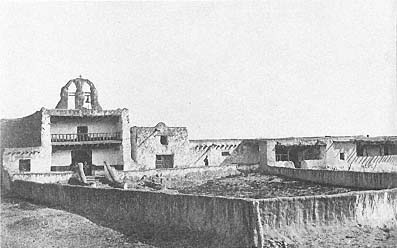

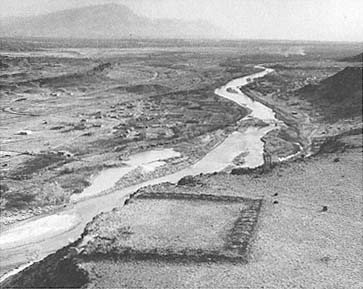

17–2

Pecos Pueblo

Restoration of the Pecos settlement about 1700 by

S. P. Moorhead. The mission and convento are in the

upper left.

[Courtesy of the R. S. Peabody Museum]

a clear view of the surrounding land. A spring within the pueblo's walls provided the water, as did a second spring to the east and Glorieta Creek.[5] The Pecos River helped irrigate the crops, including the cotton used for weaving. On January 1, 1591, Gaspar Castaño de Sosa, in full battle dress, took Pecos and noted in his Memoria that the village possessed sufficient firewood and building timber to allow each family to build more or less at will.[6]

Pecos was established in 1598 as the headquarters of the eastern division, and a church was built.[7] Kessell noted that "if even the structure was used, it must have been only briefly." It was built about a thousand feet northeast of the pueblo and measured twenty feet by thirty feet; it was built of stone, plastered inside and out, and faced south. Given the limited space available for construction on the narrow mesilla, there was no convento.[8] The threat of an Indian uprising forced the friar to leave, and the church was subsequently razed. Only in 1616 were friars once again dispatched to the pueblo.

During that year a Franciscan was assigned once again to Pecos, and a sanctuary, Nuestra Señora de los Angeles (Our Lady of the Angels), was constructed or rebuilt. Although the structure might have been scanty, with the priest still living somewhere within the south part of the pueblo itself, a dedication took place on August 2, 1617 or 1618, the feast day of the patron saint.[9] The second church arose on a site two hundred feet south of the pueblo structure, attempting to minimize its vulnerability to potential raiders. Fray Pedro de Ortega is credited with initiating the works, and by the early 1620s enough of a convento had been completed to provide him with lodging.

The uneven site required considerable fill to level its floor, similar to those problems at San Ysidro at Gran Quivira or San José de Giusewa at Jemez Springs. Its foundations, however, lay on solid bedrock. Construction continued during the jurisdiction of Fray Andrés Juárez, although how much he accomplished has been difficult to ascertain. Juárez, who had entered New Mexico in 1612 and had stayed at Santo Domingo before his assignment to Pecos, wrote to the viceroy on October 2, 1622, that

a temple is being built in this pueblo de los Pecos de Nuestra Señora de los Angeles because it has no place to say Mass except for a jacal in which not half of the people will fit, there being two thousand souls or a few less. And then, God willing, it will be finished with his help next year. Therefore I beg Your Excellency, for the love of our Lord, please order that an altarpiece featuring the Blessed Virgin of the Angels, advocate of the pueblo, be given, as well as a Child Jesus to place above the chapel which was built for that purpose.[10]

He continued with comments on trade between Spanish and Indian groups, noting that "many times when they come they will enter the church and when they see there the retablo and the rest there is, the Lord will enlighten them so that they want to be baptised and converted to Our Holy Catholic Faith. And in all the good that results from the altarpiece Your Excellency will share."[11] Clearly the intention behind construction of a significant edifice was not only to glorify the Lord but also to serve as a propaganda device for the divine work.

Although the claim to a church large enough to hold the whole pueblo of nearly 2,000 could have included the use of an atrio, this second church still commanded respect.[12] Benavides, visiting the territory from 1625 to 1629 to inspect the missions and encourage their development, termed Nuestra Señora de los Angeles de Porciúncula "a convent and church of peculiar construction and beauty, very spacious."[13] Alden Hayes recorded its dimensions as 133 feet long by 40 feet wide at the east entrance, about 45 feet high (almost two times the height of what is seen today), with walls up to 10 feet thick.[14] Agustín de Vetancurt called it a "magnificent temple . . . adorned with six towers, three on each side," with walls so thick "services were held in their recesses."[15] The quality of its woodwork—Pecos was noted for its fine Indian carpenters—matched the scale of the enterprise. A two-storied convento abutted the church to the west, the priest dwelling in the upper story. As the seventeenth century came to a close the mission at Pecos stood firmly established, with its structure a physical statement of the presence and importance of the church.

If Indian-religious relations appeared to be relatively stable, those between the civil authorities and the church remained volatile. Colonists usually came to New Mexico with the intention to gain. "The governor had to buy his position and neither he nor his men were paid by the Crown."[16] Obviously this prompted exploitation—either of the land or its inhabitants—to extract financial reward. Under the jurisdiction of governors like Luis de Rosas (governed 1637–1641), the situation became intolerable. Rosas was a harsh man, demanding quantities of blankets from the Pueblos and forcing Christian pueblos to work with the detested Apache and Ute under intolerable conditions. He traded knives for buffalo hides and meat with the Apache and engaged in a campaign of exploration and lucrative commerce.[17] Although an extreme example, his term of office was indicative of the typical pat-

tern, which forced the missionary to act at times as a powerless intermediary. This pattern did little to aid evangelical efforts among the Indians. Yet an inventory, probably of 1641, stated that the mission "has a very good church, provision for public worship, organ, and choir. There are 1,189 souls under its administration."[18]

As was the case in most of the missions, the Pueblo Rebellion of 1680 brought the first chapter of its history to a close and inaugurated the second. The insurrectionists ignited piles of juniper and piñon, setting the roof of the church afire. The clerestory now served as a chimney vent, sucking in air and expelling ashes out the door.[19] Walls were pulled down, and the facade tumbled into the nave, covering the ashes of the pyre. The work of more than six decades lay buried by adobe.

With the Reconquest, plans were made to reestablish the missionary presence at Pecos and to restore or rebuild the fallen structure. Within a year Vargas turned his attention to these matters and wrote the viceroy, although his primary interests were military and strategic as well as evangelical. "At the pueblo of the Pecos, a distance of eight leagues from Santa Fe, 50 families could be settled, because it too [like Taos] is an Apache frontier and, being so surrounded by very mountainous country, suffers unavoidable ambush. Settled in this manner, and backed by the military of the villa, it will prevent the robberies and murder that follow from assured entry. It is very fertile land which responds with great abundance to all kinds of crops planted."[20] By the following year a (rebuilt) church stood on the site, but curiously it was reconstructed adjacent to the nave of the earlier structure. Utilizing the remnants of the north wall of the old convento but reversing the orientation, it measured about twenty feet by sixty to seventy feet. The structure was hastily built under the direction of Fray Diego de Zeinos, who stayed about a year at the pueblo but was ultimately removed to ease tension after accidentally shooting an Indian.[21]

Vargas visited the site in the fall of 1694 and was assured that the pueblo "would build their church in order that divine worship might be celebrated in greater decency than at present. They have provided for the construction of a chapel which they provided by showing me the beams for to roof it. . . . They had rebuilt for [the reverend] its very ample and decent convento and residence."[22] Improvements continued as part of the process of use and construction. Vargas recorded in November 1696 that they had "added to the body of the church by increasing the height of the clear story [sic ], and to the sanctuary by adding two steps to the main altar, and had walled in the sacristy and had closed the portion at the entrance to the convento with a wall."[23] Even though the walls and roof were improved periodically, the process of deterioration by the elements subverted efforts to maintain the church.

By 1705 Fray José de Arranegui had undertaken the building of a new structure, although he continued to use the makeshift chapel built on the ruins of the prerebellion church. In 1706 Fray Juan Álvarez reported that construction was under way.[24] Kessell cautioned, however, that Alvarez made a similar claim for fifteen other pueblos including Acoma, where the pre-1680 church still stood, and he may actually have been noting substantial repairs rather than truly new construction.[25] This was to be the fourth and last church at Pecos pueblo, three times the size of the Zeinos structure but not as large as the Juárez sanctuary. Thus, the last effort fit within the walls of the second church, although it maintained its reversed orientation to the west. Two bell towers flanked the main door and formed a shallow narthex. A clerestory illuminated the nave, augmented by one window high on the north wall and three facing south overlooking the convento. Construction was probably complete by 1787. The old convento was still habitable and retained more or less the same form, although probably with a nominal degree of repairs and upgrading. The raggedly profiled mound of red adobe that one sees today is primarily the ruin of this church.

The remainder of the Pecos ecclesiastical story is one of dissolution and decay. Although the pueblo occupies an excellent site within the valley, its vulnerability to Apache attack increased as the population declined. In 1694 there were 736 inhabitants, but smallpox epidemics in 1738 and 1748 reduced the population to one-fourth of that figure. Yet there were still moments of glory among those of depression, moments of pride within the confines of the vows of poverty. Fray Juan Miguel Menchero recorded in 1744 that "the construction was done through the industry and care of the Father of the mission without having spent even a half-real of His Majesty's funds." The church, he said, was "beautiful and capacious."[26]

Bishop Tamarón visited the church, but he left no specific comments or criticism; he was, however, troubled by the problems in communications between clergy and congregation. "Here the failure of the Indians to confess except at the point of death is more noticeable, because they do not know the Spanish language and the missionaries do not know those of the Indians." Perhaps this was by choice.

17–3

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles, Plan of the Seventeenth-Century Church and Convento

[Source: Hayes, The Four Churches ]

17–4

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles, Plan of the Eighteenth-Century Church and Convento

[Source: Hayes, The Four Churches ]

17–5

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles, Hypothetical Restoration of the Eighteenth-Century Church and Convento

[Lawrence Ormsby]

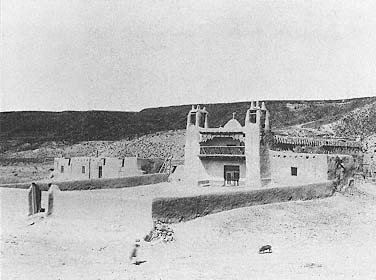

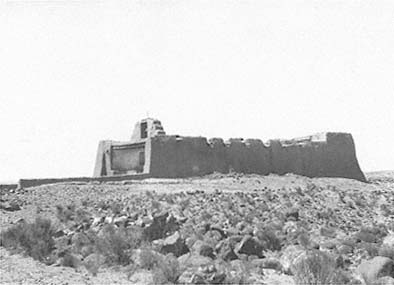

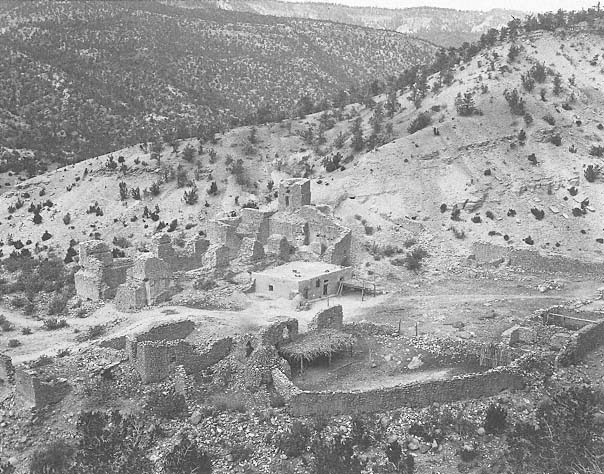

17–6

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles

The massive ruins of the eighteenth-century church fit within the

crenellated footprint of the towers that buttressed its predecessor, the

post–Pueblo Revolt structure.

[1981]

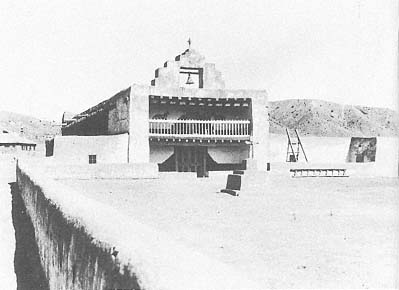

17–7

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles

Lithographic view of the mission ruin in 1846.

[From Calvin, Lieutenant Emory Reports ]

"In trade and temporal business where profit is involved, the Indians and Spaniards of New Mexico understand one another completely. In such matters they are knowing and avaricious. This does not extend to the spiritual realm, with regard to which they display great tepidity and indifference."[27]

At the time of the 1776 Domínguez visit both the newer structure and the remains of the older one still stood.

As we enter the [newer] church, on our right under the choir is the entrance to an old church outside the wall. The old building extends to the south, with the door where I said, and is joined to the convent on the Epistle side. And in order not to become involved, I state now that it is a size to fit in the nave of the one we are describing and that it is falling down. As we enter this old church, outside its wall on the left is the sacristy now in use, and the baptistry now in use is on the right, also outside the walls, and the entrance to both rooms is from the old building.[28]

Domínguez found at least two aspects of the complex worthy of comment: "All the beams in the roof are well wrought and corbeled," and the "two beautiful stables, each with a straw loft that was a part of the convento structure."[29]

De Morfi's 1782 description testified to the continuing demise of the community:

In 1707 it had about 1,000 souls. In 1744, 125 families, in 1765, 178 . . . families, with 344 persons. Today 84 inhabit it. It suffered such a considerable decline, being the frontier for enemies who with pretext of peace frequented it and took the opportunity to wreak havoc.

It has a capacious and beautiful church and a convent where two religions lived previously; today there is only one.[30]

The pueblo continued its downward spiral. Disease and raids took their respective tolls, and there was little chance of reversing the process of dissolution. After 1782 Pecos suffered the reduced status of a visita of Santa Fe and, in 1820, of San Miguel del Bado.[31] At the turn of the century "land-poor" Spanish settlers were admitted to the pueblo lands, and the independence of the village as an entity was completely undermined. By 1820 the imbalance was already apparent: the census listed 58 Pecos Indians and 735 Spanish settlers. The last entry in the church's book was recorded in 1829. Nine years later the remaining 17 to 20 Pecos Indians left for Jemez, with the Hispanic settlers agreeing to celebrate the Feast of Nuestra Señora de los Angeles each August 2.[32] This, then, was the final end of the village that Benavides had noted "of Jemez nation and languages . . . 2,000 Indians and a very fine mission."[33]

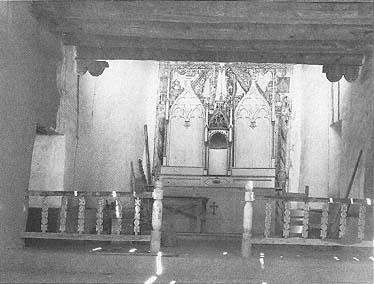

17–8

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles

Excavation and stabilization of the church ruins in December 1940.

[W. J. Mead, Museum of New Mexico]

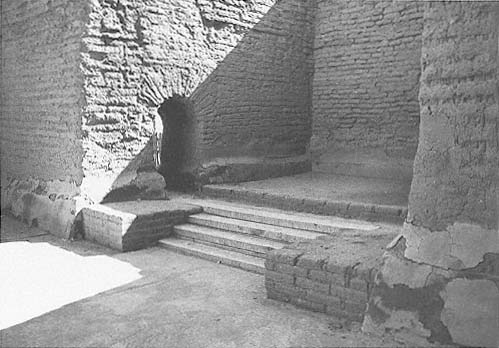

17–9

Nuestra Señora de Los Angeles

The chancel of the eighteenth-century church with an adobe arch, a rare building element in

New Mexico.

[1981]

Pecos today is an impressive monument, even in pieces [Plate 6]. On the narrow mesilla are the ruins of the pueblo itself, excavated by Alfred Vincent Kidder from 1915 to 1925 in the summers; these excavations figured prominently in the formulation of southwestern archaeology. Kidder believed the cellular configuration of the structure, clustered around a plaza, to be indicative of a preconceived plan built for defense. The southern group remains unexcavated but is visible as a mound between the church and the visitor center.

Today the remains of both the postrebellion church and the final, fourth church are discernible. Of the two, the younger structure is the more dominant. The western part of its construction is completely eroded, although the considerable bulk of the apse end remains. Constructed of adobe stacked to a thickness of almost six feet, the nave is articulated into two shallow transepts and steps up into the chancel, which once contained the altar. Behind the altar in the north wall is one of the rare remaining instances of the arch in New Mexico.

Like its predecessor, the fourth church boasted two towers and a balcony spanning the entrance. The structure lasted well into the nineteenth century. Emory made a record of Pecos in 1847 on his expedition for the U.S. Army, and at that time the church, although deteriorated, still bore vestiges of its earlier form. Like Domínguez, Emory was impressed by the woodwork.

Here burned, until within seven years, the eternal fires of Montezuma, and the remains of the architecture exhibit, in a prominent manner, the engraftment of the Catholic Church upon the ancient religion of the country. At the end of the short spur forming the terminus of the promontory are the remains of the "estuffa", with all parts distinct, at the other are the remains of the Catholic church, both showing the distinctive marks and emblems of the two religions. The fires from the "estuffa" burned and sent their incense through the same altars from which was preached the doctrine of Christ. Two religions so utterly different in theory, are here, as in all Mexico, blended in harmonious practice until about a century since, when the town was sacked by a band of Indians. . . .

The remains of the modern church with its crosses, its cells, its dark mysterious corners and niches, differ but little from those of the present day in New Mexico. The architecture of the Indian portion of the ruins presents peculiarities worthy of notice.

Both are constructed of the same materials; the walls of sun-dried brick, the rafters of well-hewn timber, which could never have been hewn by the miserable little axes now used by the Mexicans, which resemble, in shape and size, the wedges used by our farmers for splitting rails. The cornices and drops of the architecture in the modern church are elaborately carved with a knife.[34]

Two diagonal braces reinforced the balcony span, eliminating the need for central columns like those seen in early photographs of Cochiti and Zuñi. But the abandoned structure suffered under the forces of nature and the neighbors.

Hewett reported that as late as 1858 the roof still remained in place.[35] A widowed Mrs. Kozlowski told Adolph Bandelier that her husband had removed the timbers and used them to build or roof structures (outhouses) on his property. Bandelier visited the site in 1880 and wrote of it, "The ruins first strike his [the tourist's] view: the red walls of the church stand boldly out on the barren mesilla , and to the north of it there are two low brown ridges, the remnants of the Indian houses."[36]

In 1915 a significant chapter in New World archaeology was inaugurated with the beginning of excavation at Pecos by Alfred Vincent Kidder, who was followed by Jesse L. Nusbaum of the Museum of New Mexico. The site was registered as a state monument in 1935, and in 1965 it was elevated to National Monument status, administered by the National Park Service. The area of the monument was further increased in the 1970s with the donation of additional land.[37] A new interpretive center was added early in the 1980s.

The imposing red mass of the church dominates the site and the valley—an earthen lump that can be seen from miles away. Visiting the site, one will see not only the church and convento ruins and the pueblo structure but also the stabilized foundations of the second church, easily ascertained by its dentilated profile—the foundation of the "six towers" cited by Vetancurt. On the narrow mesilla at Pecos, one derives a clear picture not only of the sequencing of the four structures that occupied the land over a period of two centuries, but also of the relationship of the church to the pueblo. At first the church was separate from the pueblo; later, perhaps for defense, the church was closer or even abutting the village; but it was always a distinct entity that relied primarily on the topography of the ridge for its sense of connection.

Cochiti Pueblo:

San Buenaventura

pre-1637; c. 1706; c. 1900; 1960s

At the bottom of the basalt flow that extends southward from Santa Fe, where the Rio Grande cuts deep into the terrain, lies the pueblo of Cochiti. Always aware of the surrounding mesas, today the community is further dwarfed by the great earthen dam that has transformed the Rio Grande behind it into a shallow lake. But the river squeezes through the sluices and then comfortably flows once again through the cottonwoods and shrubs that surround the pueblo. Earle Forrest described Cochiti in 1929 as a nearly perfect pueblo: "Cochiti contains everything that goes to make an interesting pueblo; an ancient catholic mission in charge of a priest from Peña Blanca, two large kivas where members of the Turquoise and Calabash clans still strive to keep alive the religion of their fathers in spite of the fact that most of these indians are catholic, and a picturesque plaza in the center of the village."[1] The scene, alas, is not as perfect today, nor is there a marked consistency to the buildings of the village.

The pueblo, as the northernmost of the Keresan group, claims its origins in the Tyuonyi and Frijoles canyons, where the early dwellings were enlargements of natural caves dug in the soft tufa stone (now part of Bandelier National Monument). Subsequent settlement was invested in two or three separate locations before the group eventually split in two, forming the pueblos now known as San Felipe and Cochiti. Other linguistically related Keres speakers include Santo Domingo, Zia, Santa Ana, and the western pueblos of Acoma and Laguna. Bandelier claimed that Cochiti was one of the group of eight Keresan pueblos named by Pedro de Casteñeda, the chronicler of the Coronado expedition.[2] In the fall of 1581 the Chamuscado-Rodríguez expedition was supposed to have reached the pueblo, described as having 230 houses of two and three stories and named Medina de la Torre.[3] The following year the Espejo expedition also stopped at Cochiti and described the people as being "very peaceful." They provided the Spaniards with foodstuffs such as turkey and maize and traded skins for iron goods.

The date of the mission's founding is not known, but Forrest assumed it to be early in the 1600s, the same as the nearby Nuestra Señora de la Asunción monastery associated with San Felipe Pueblo.[4] Benavides mentioned Cochiti but only as one of three churches and conventos serving the "Queres Nation."[5] Throughout the seventeenth century, Cochití remained a visita of Santo Domingo mission, although in 1637 the presence of a resident friar was noted.[6] In 1642 Cochití was said to "have a church."[7] A 1667 reference was the first to attribute the mis-

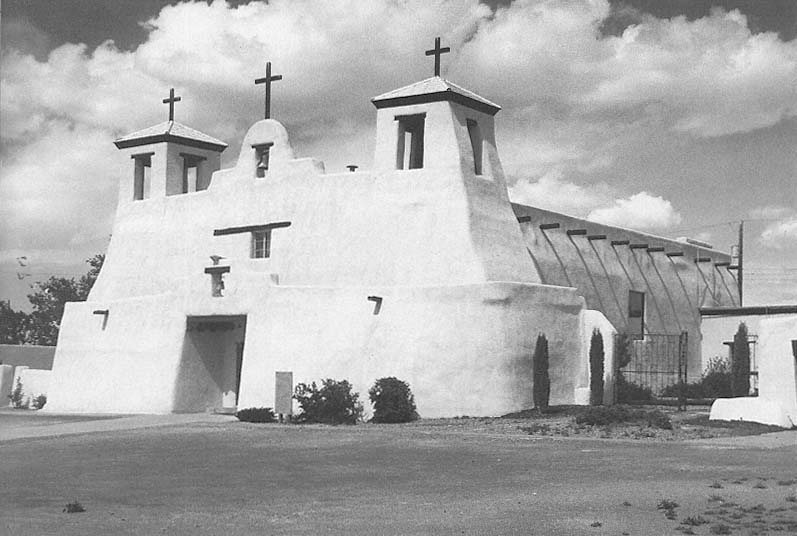

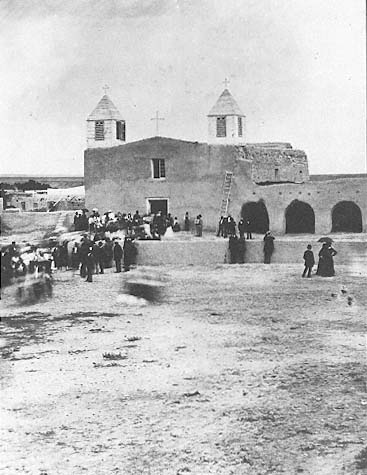

18–1

San Buenaventura

1890s

The balcony stretching between the extended side walls was sagging noticeably at the turn

of the century.

[Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives]

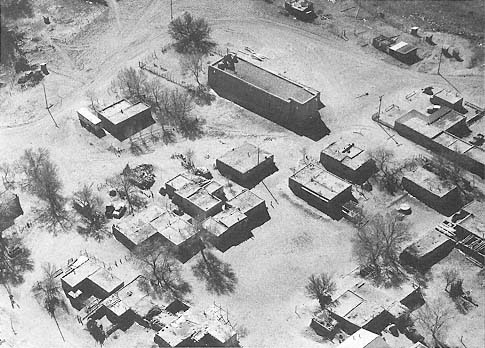

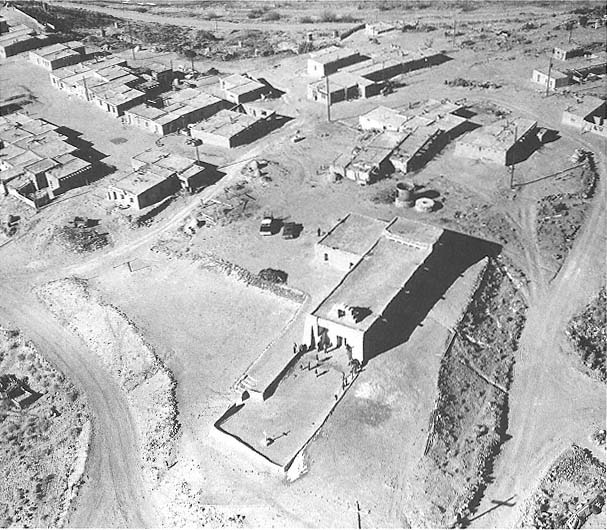

18–2

Cochiti Pueblo

A portion of the pueblo from the air.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

sion name to San Buenaventura, who remains the patron saint.

The early church building no doubt followed the prototype for its time and location: thick adobe walls, a single nave, a flat facade with a small arch for a bell, a beamed ceiling, and perhaps a clerestory. Although the pueblo was a "storm center" (as Prince called it) for the great revolt of 1680, no priest died there.[8] Legend has it that warned by an Indian believer, he managed to escape the pueblo. What happened to him thereafter is not known. But if the mission was a visita of Santo Domingo, there might not have been a priest in residence. In 1681 the abortive Spanish attempt to reclaim New Mexico reached Cochiti but found that the pueblo, with the warriors from San Felipe and Santa Domingo, had fled to Horn Mesa, which rises about seven hundred feet above the village. Again in 1693—the Reconquest—the Indians withdrew and fortified an adjacent hilltop but were coerced by the Spanish to peacefully return to their fields and pueblos. The peace did not last. In April 1694 Vargas returned to find the Cochiti people once again entrenched on the mesa top.[9] This time efforts toward peaceful negotiations were unsuccessful. The outcome was that the few Spanish, augmented by forces from the now pacified and allied San Felipe, Santa Ana, and Zia pueblos, stormed the summit and took the battle, large stores of food, and many captives.

The prerebellion church lay in ruins, and Vargas ordered a new church built in place of the old. How much was constructed before the subsequent revolt of 1696 is not recorded, but in 1706 the mission was still, or again, in poor condition. Fray Juan Olvarez reported, "This mission has a broken bell without a clapper. (The Indians took all the clappers away, to make lances and knives.) There is one of the ornaments which his Majesty gave. The vials are a silver one, another of tin plate. The church is being built. This mission has about five hundred and twenty Indians. . . . It is called San Buenaventura de Cochiti."[10]

Whether this meant, as it often did, that the roof was being replaced, or that work from 1694 or post-1696 continued, is not certain. Bishop Tamarón in 1760 left no description of the physical structure, although he had only mixed reactions to the parishioners: "The catechism was put, and the Indians were prepared. They do not confess and are like the rest." There was a priest in residence at the time of Tamarón's visit, and the population stood at 450 persons.[11]

A decade and a half later Domínguez summed up his remarks by calling the interior "very gloomy." Once again he sought in vain the brilliance of the central Mexican religious interior. "The church is adobe with walls about a vara thick, single-naved, with the outlook and the main door due east."[12] Unlike today's church, the nave continued to the apse with no diminishing of width and did not include a choir loft. A clerestory and two "poor" windows facing south illuminated the interior. "There is a little belfry over (the main door) with a good middle-sized bell that the King gave."[13] "Adjacent to the church on its south side, there is a porter's lodge, which is a very pretty little portico to the east without pillars in front of it because it is very limited. The floor of this little portico is paved with small stones like those mentioned. There are adobe seats around this room, and the door is in the center of the wall."[14]

Rounding out the list of major structures was the corral, often an integral part of the religious complex. Here was kept the friar's stock as well as his means of transportation. "The corral is against the convent on the south, runs from the upper to the lower corner and is about 8 varas wide. It has a rather high adobe wall and a great two-leaved door without a lock to the east. Against the south wall in the corral are stable and strawloft, both very large rooms."[15]

The "very gloomy" church remained in eighteenth-century form until past the turn of the century, when its condition showed signs of grave deterioration. As was often the case, the neglect of the church's maintenance led to major repairs, in turn suggesting a considerable rebuilding or updating in style. Although not the resident priest, Fray Francisco de Hozio wrote to Governor Facundo Melgares in 1819 requesting that the governor aid in securing the services of a certain mason named Madrid who lived near Santa Cruz. "I have arrived here without incident and found this church in a state that caused me much sorrow since with the greatest ease it could have been finished by now. . . . I beg you therefore, by virtue of your authority, to make Madrid come and lay the adobes there are. Indeed I am of the opinion that with two days work it will be to the bed molding."[16]

The content of the letter suggests that the church was unroofed at the time, at least in sections, and that the replacement of the vigas was awaiting the final courses of adobe bricks. It seems curious that with the resources available to the Indians of the pueblo, their long experience with adobe, and the considerable sections of the church walls still remaining that the father felt it necessary to call on a Spanish or mestizo mason from fifty miles away.

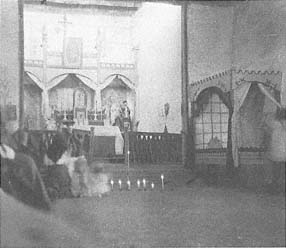

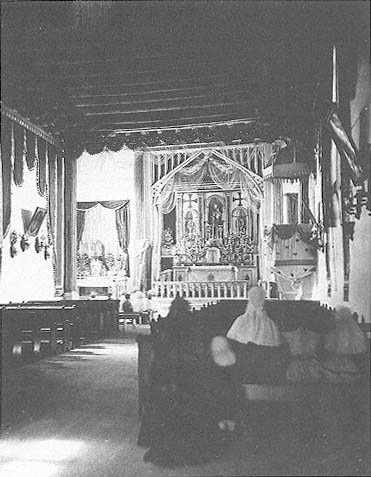

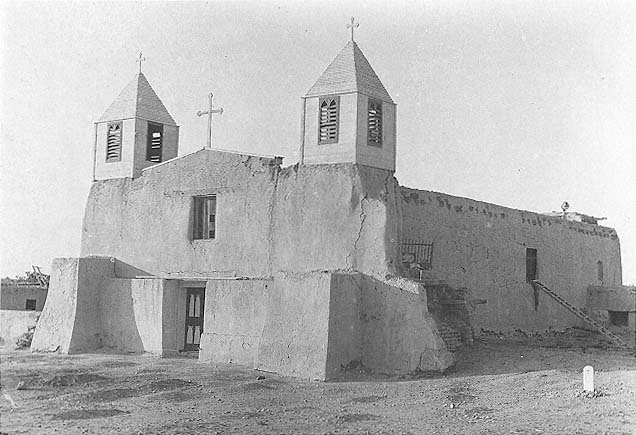

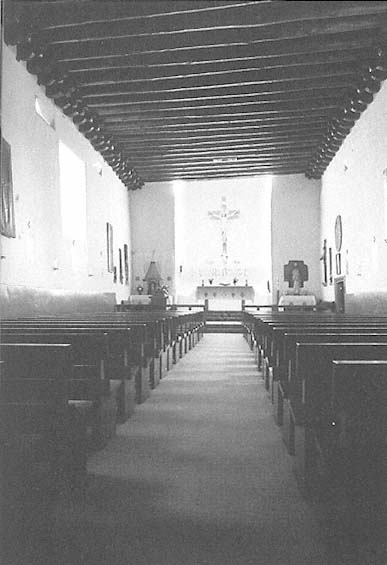

18–3

San Buenaventura

circa 1900

The interior of the church with its raised sanctuary.

[Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives]

Perhaps there had always been continual reliance on the building skills of the Spanish colonists in the construction of large edifices such as churches. Perhaps the construction was always under the supervision of a builder rather than the missionaries themselves. Or perhaps the Indians were just not interested.

In any event three days later the governor ordered the alcalde of Santa Cruz de la Cañada to send "the mason Madrid under appropriate guard to Cochiti to build up the church, on the basis that he should have done it already."[17] The work apparently was done. Kessell suggested that some major modifications to the building fabric were undertaken at this time: the narrowed chancel, the two towers, the shallow balcony, and the choir loft that had not been in its "usual place" to greet Domínguez.[18]

The remainder of the century passed uneventfully. Nevertheless, when Lieutenant John Bourke visited the church in 1881, he wrote:

The church of [San Buenaventura at] Cochiti [is] very old and dilapidated; the interior is 40 paces long to the foot of the altar by 12 broad. It is built of adobe and whitewashed on the inside—Altar pieces showing signs of age—swallows making their nests in rafters. Ceiling of riven slabs, nearly all badly rotten and those which had been nearest the altar have been replaced by pine planks covered over with Indian pictographs in colors—red, yellow, blue & black. Buffalo. Deer, Horses, Indians, Indians in front of lodges, X [cross] and other symbols. Olla used for holy water font. The cross had fallen from the front of the church and its whole appearance is strongly suggestive of decrepitude and ruin.[19]

Early photos from 1889 and 1900 by Vroman and others show the church in the condition Bourke described. The plaster has eroded, the walls look beaten, and the large beam that supports the balcony on the eastern front groans under the weight of its load. Vroman's interior photo, however, depicts a tranquil world in repose: the interior is empty, there is a bare earthen floor, and the altar-piece, flanked in symmetrical balance by two smaller paintings, fills the sanctuary. The walls, whitewashed and stained with a darker dado, support the tin candle holders Prince claimed originated in Chihuahua. The ceiling of the chancel is painted "grotesquely . . . with geometrical figures in high colors, red and yellow and black, while representations of moons, horses, etc., are interspersed without any apparent design."[20] The soft light that falls on the altar attests to the presence of the clerestory. Although the exterior is sadly deteriorated, the interior seems to be holding its own.

18–4

San Buenaventura, Plan

[Source: Kubler, The Religious

Architecture ]

But then in 1900 Austrian Franciscans took custody of the church, and the strong winds of change began to blow. Of course, repairs were necessary, but the forms these repairs took were unduly severe and rather insensitive. No doubt the fathers believed that this was an opportunity not only to repair the church but also to update its style as well. If San Felipe and Santo Domingo were spared the trauma of remodeling, Cochiti, although administered by the same custody at Peña Blanca, suffered the imposition of an imported architectural style. The walls were patched and replastered, and a pitched roof of corrugated metal was erected over the entire church. Topping it in good Anglo fashion was a steeple some twenty feet high. At the front a portico of three arches replaced the open balcony/ narthex—arched forms that would have been more comfortable in California, having been almost nonexistent in New Mexico. Photographs from this period portray a building so drastically revised that it would be almost impossible to match it with the form of the preceding structure. Of course, this was no doubt the intention—to create a distance between the "new" church and its predecessor. The steeple, however, caused structural problems. From the beginning its height exaggerated its wind-catching propensity and threatened to seriously crack the walls below. In short order it was lopped off to a truncated stump.

Even at the time of the remodeling in 1910, there must have been some outcry from those beginning to appreciate the rapidly deteriorating Hispanic colonial heritage in New Mexico. They were addressed directly by Father Jerome Hesse, who wrote about the remodeling in 1916 with a great sense of pride and righteousness:

The appearance of the old, venerable church of the pueblo has been changed completely, to the chagrin of the archeologists, it is true, but to our own great pleasure and satisfaction. Some years ago the mud roof was replaced by a substantial roof of corrugated iron, and last year the interior of the church was renovated and decorated. First of all the bumpy, crooked walls had to be made as even as could be done before plastering; then the damp floor of clay had to make way for a regular wooden floor; moreover, through the inventive genius of our Ven. Brother Fidelis, the rough logs of the ceiling were hidden by a selfmade, cheap but handsome ceiling; finally the interior was tastefully decorated. . . . The whole interior of the church underwent a complete change and assumed a rather modern appearance.[21]

If there was ever a succinct statement of the conflict between Anglo and Indian or Hispanic values, this must be it.

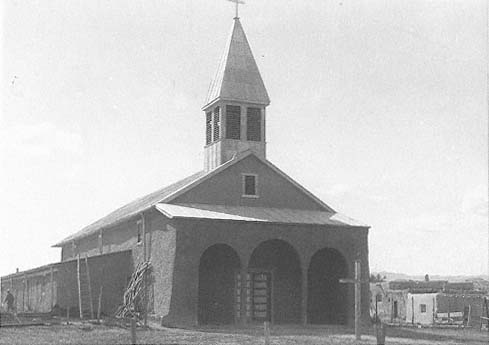

18–5

San Buenaventura

circa 1915

A three-arch porch has replaced the balcony, and the church wears a disproportionately

tall steeple.

[Museum of New Mexico]

18–6

San Buenaventura

1949

In response to the threat of structural failure, the tall steeple has been trimmed, helping return

the building to the earth.

[New Mexico Tourism and Travel Division]

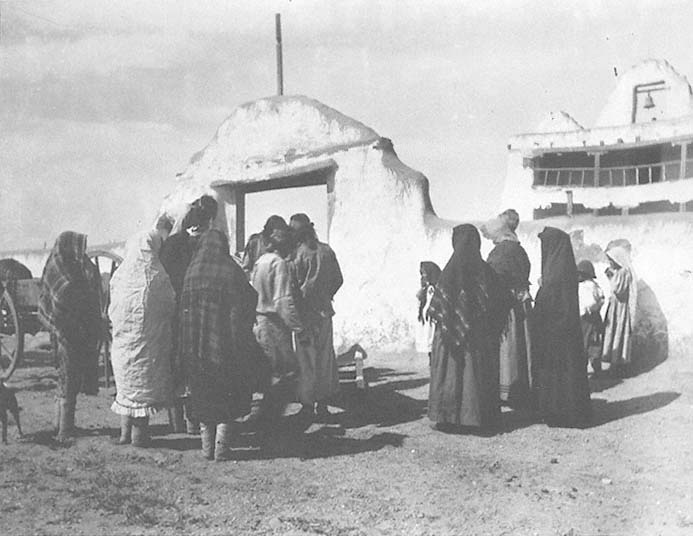

18–7

San Buenaventura

A funeral pauses at the entry to the campo santo.

[Museum of the American Indian, Heye Foundation, F. Starr Collection, 1894–1910]

The archaeologists, and most of the writers, however, were not happy. In 1918 Paul Walter responded, "The beautiful Cochiti mission church . . . has been unfortunately transformed into a nondescript chapel with a huge tin roof and an arched portal, evidently an attempt to mimic the California mission style."[22] In 1929 Forrest was no kinder.

The modern destructive spirit which has ruined several of New Mexico's ancient monuments reached out its hand to Cochiti, and a few years ago the exterior of the old edifice was so altered that it looks more like a visitor from some eastern hamlet. This is the only discordant note in an otherwise perfect Indian pueblo. The old flat roof and picturesque Franciscan belfry have been replaced by corrugated iron and a high pointed steeple. The balcony was removed and the entrance was enclosed by an adobe porch with three arches, the only attempt at ornament.[23]

To those extolling the greatness of the missions as they were, the remodeling was a sacrilege. Fray Angelico Chavez, noted authority on the missions, discussed a re-remodeling with pueblo authorities as early as the 1930s,[24] but the actual work waited until the mid-1960s when Santa Fe architect Robert Plettenberg prepared the design of the current structure based on old photographs and descriptions. Certainly the result is happier than the Victorian revisions, although new construction can hardly restore the old quality, which is the product of years. While the facade reasonably approximates the look of the church prior to 1910, elements of the bell arch and beam work are turned comments on the old. The use of a hard cement stucco is another expedient: no covering material for adobe walls produces the same properties as mud plaster, whose deterioration acquires character over time, unlike the sadness of cracked and chipped stucco. The restoration, like the reconstruction at San Ildefonso, is comforting to some extent. Perhaps as time operates on this new building, and it is patched, augmented, and eroded, even in stucco, it, too, will acquire a patina of significance.

Earle Forrest was still moved by the simplicity and the beauty of the Catholic mass at Cochiti on July 14, 1929, at the time of the annual festival:

During the morning, mass is held in the old mission by a priest from Peña Blanca. The service is typically indian, and when you enter the church you step back across the centuries to the old Spanish days. Kneeling in the nave, which is without seats, the men on one side and the women on the other, are the indian neophytes with bowed heads listening to the blackgowned padre as in the days of old, while an indian choir sings at intervals from the gallery above.[25]

Cochiti today lacks the architectural coherence it possessed historically, even until early in this century when it was described as "the nearly perfect pueblo." The changes in the job market, the construction of federally sponsored detached houses at the periphery of the pueblo, and the impact of recreation and new development spawned by the Cochiti Dam have all taken their toll. But there is still a quality to the place, and to all pueblos, that speaks of a connection with the past and a connection to the earth.

Santo Domingo Pueblo:

Santo Domingo

1607; 1706; 1754?; 1895 (new site)

Many of the pueblos suffered at the hands of the Spanish or other tribes; for the churches destruction was often caused by the depredations of the Comanche or the Apache. The Salinas missions were ravaged by drought and, like many of the villages, by the communicable diseases that accompanied the Europeans. Santo Domingo, in addition to all these other problems, was also plagued by flood.

There have been four settlements in the vicinity of the current pueblo; the first, called Gipuy by Forrest, lay about two miles east of the present Santo Domingo.[1] It was here that Oñate founded the monastery of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción. This was the second pueblo of that name to exist on the site, the first, tradition has it, having been destroyed by the high waters of the Galisteo River prior to 1591. Gaspar Castaño de Sosa rechristened the village Santo Domingo when he stopped there in 1591. Both the pueblo and early efforts to found a Catholic mission there were dashed by floodwaters again in 1605. A new village, almost coincident with today's Santo Domingo, was founded shortly thereafter, moved further eastward as its western edge was lost to the river.

A new church structure arose in 1607 under the direction of Juan de Escalona, and in 1619 Santo Domingo became the ecclesiastical headquarters of the province. Relations between the religious and the Spanish civil and military authorities were not always the best during the early seventeenth century. The church precinct was apparently strengthened to such a degree that the friars were charged with constructing fortifications and storing munitions and other defensive supplies within the convento.[2]

Although Santo Domingo was not specifically named by Benavides, he attributed seven pueblos to the "Queres nation, commencing with its first pueblo, San Felipe. It contained 7,000 souls, 'all baptized,' three convents and churches, very spacious and attractive, in addition to one in each pueblo." He credited Fray Cristóbal de Quirós with conducting training in the Catholic faith but also "in the ways of civilization, such as reading, writing, and singing."[3] By midcentury Santo Domingo was said to have "a very good church . . . a choir, an organ, and many musical instruments; its convento was 'good.'"[4] Almost a century and a half later music was still a notable part of the service.

Indian vengeance struck swiftly during the 1680 Pueblo Revolt, and within two days the three priests at the pueblo were killed. Governor Antonio Otermín and his party of refugees passed through the village on their forced flight south and found the church securely locked. They broke open the fas-

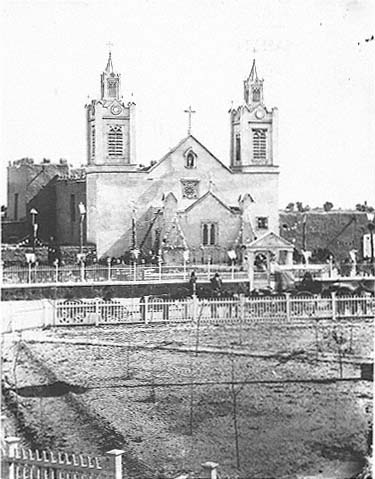

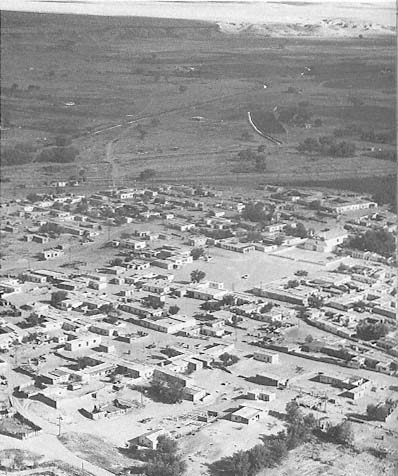

19–1

Santo Domingo

Seen from the air, the linear organization of the pueblo is clear. The church is in the upper left.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

tenings and discovered a large mound of earth in the middle of the nave. Subsequent digging uncovered the bodies of the three missionaries buried in their Franciscan robes. But the physical aspects of the structure stood unmolested, and the retreating Spaniards removed the ornaments, vessels, and pictures and carried them to El Paso del Norte.

To what extent the church itself was damaged is not known, but during the attempt to retake the lost province in the following year, one of the soldiers recorded that

they marched to the pueblo of Santo Domingo where they found things in the same condition as in the others. All the churches had been demolished and burned, and yet in all of them, as had been stated, the Indians' kivas had been built. The apostates had rebuilt the principal stretch of wall (lienzo ) of Santo Domingo for a fortress and living quarters. The Spanish saw in this pueblo a large number of masks and idolotrous objects.[5]

Perhaps, Kubler queried, the church was rebuilt prior to 1696 and ruined in the incidents of that year; or perhaps the remains of the old structure were extended and refurbished in the construction of 1706.[6] The site of the pueblo was shifted to the current location around 1700. Some time after the arrival of Fray Antonio Zamora in 1740—1754 is a date suggested in one "vague" report—a larger church was constructed at the padre's own expense. "Thus in 1776 Santo Domingo had two churches, side by side facing south, an old one relegated to burials and passage to and from the convento, and a thick-walled newer one, both 'in full view of the Rio de Norte,'" explained John Kessell.[7]

Tamarón visited the mission in 1760 and commented more on the state of the souls than on the condition of the structures. The next reports, these in the usual excruciating detail, were those of Domínguez in 1776. "Father Zamora," he began,

built it [the church] out of his alms. It is adobe with very thick walls, single-naved, and the outlook and main door are due south. The choir loft is in the usual place and like those of the Rio Arriba missions, and the entrance is an ordinary single leaf door with a key. It is approached by a stairway of small beams between the walls of the two churches mentioned. This begins from the front corners of both and is open toward the cemetery. In the choir there is a good large niche for the musicians, who, at Father Zamora's expense, keep two guitars and three violins there.[8]

There were only rudimentary furnishings for the church. "For further adornment of the good work which I have been describing, Father Zamora had

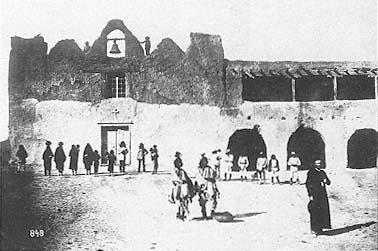

19–2

Santo Domingo

1880

In this early photograph two churches—both subsequently destroyed—are

visible. Although suffering from erosion, the bell arch displays an

exaggerated vertical note surpassing that of the old San Juan church.

[Museum of New Mexico]

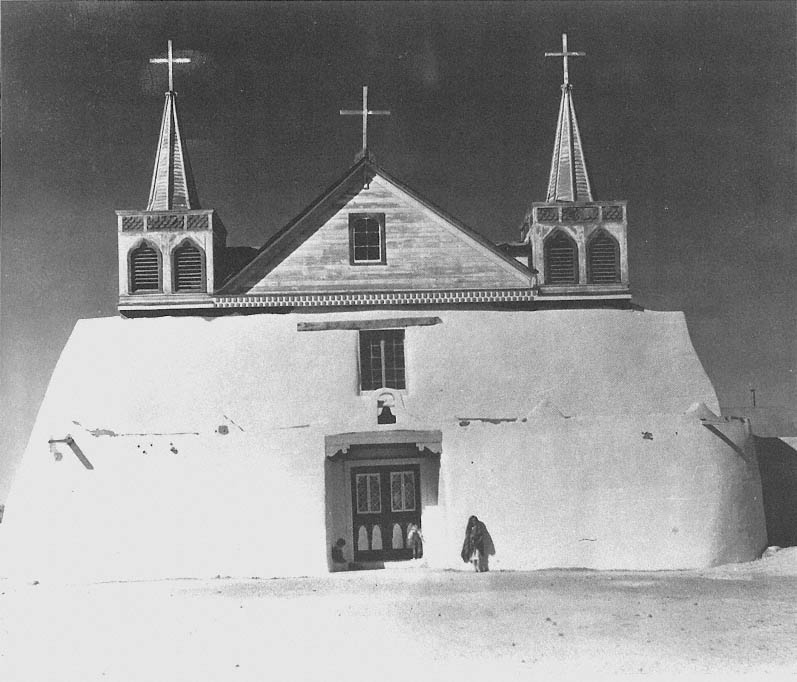

19–3

Santo Domingo

1917

Taken away by flood, the new church has been rebuilt in a safer location and

stands in good condition—neatly plastered.

[Museum of New Mexico]

19–4

Santo Domingo

circa 1907–1910

The clerestory is oriented toward the west, receiving

the afternoon light.

[Museum of New Mexico]

a small altar screen in perspective painted on the wall at his own expense. Although it is an ordinary painting in tempera, it is very pretty and carefully done. It is in two sections and does not reach the ceiling."[9] This reredos, which features an image of the patron Santo Domingo carved in the round, had been painted by a father named Camargo and shipped from Mexico.

The plan of the pueblo differed noticeably from the layout of the other pueblos except, perhaps, for a weak formal simultaneity to that of Acoma. Instead of the more typical plaza-centered arrangement, Santo Domingo was, and still is, arranged in roughly parallel linear blocks.

The pueblo consists of six blocks, or buildings, of dwellings. Of these, two stand one after the other below the right corner of the new church, and face due east overlooking the church and convent to their left side on the north and to the south side on their right side. The four remaining blocks face due south with their backs to the church and convent. They are all separate from one another, with a street in the form of a cross dividing the four.[10]

There was, however, a plaza in the pueblo: "The houses have upper and lower stories like those I described at Tesuque, and these are better arranged than the ones there, with a beautiful plaza overlooked by the last ones mentioned between their facades and those of the church and convent."[11]

An 1880 plan by Bandelier is reproduced as Figure 51 in Kubler's The Religious Architecture of New Mexico and depicts this arrangement in basically the same position, although the supposed beauty of the plaza is difficult to glean from Bandelier's sketch. The depredations of the Comanche and other Plains Indians had on rare occasions penetrated as far as the Rio Grande valley, and so, as at Taos, "the whole pueblo is surrounded by a rather high adobe wall with two gates; this is for resistance against the enemy [Indians], for day by day they show more daring against the natives of this kingdom."[12] Fray Juan Agustín de Morfi was warmer in recording the conditions in 1782: "The church is large and beautiful and attractively decorated and painted. The house of the priest is roomy and comfortable."[13]

When the American Zebulon Pike was escorted from Santa Fe to Chihuahua for interrogation, he had the opportunity to stop at Santo Domingo. He described his visit in a diary entry dated Friday, March 5, 1806, and did so in a rather casual tone, considering the harsh conditions in which he was traveling: "When we entered it [the church], I was much astonished to find enclosed in mudbank walls many rich paintings, and the Saint (Domingo) as

large as life, elegantly ornamented in gold and silver. . . . We then ascended into the gallery, where the choir are generally placed to procure the charming view frequently mentioned by visitors."[14] An unsigned 1806 inventory stated that the church had "just been repaired, well roofed with boards, the vigas very striking with their corbels and carved decoration."[15]

The church occupied a site nearby the bank of the Rio Grande, that is, northwest of the pueblo. In time the church sat directly on the banks of the river, which continually wore away at the available land. A mission report of 1831 listed floodwaters in 1780, 1823, and 1830 when two unnamed churches were lost.[16] The threat was relatively constant. John Bourke mentioned the heavy rains of the summer in 1881 in several of his journal entries, often adding that repairs to the church were necessary as a result. His sketch of the old Santo Domingo presented the structure much as its successor appears today, except that the gable then sheltered two bells instead of one.[17] In 1881 through 1884 the very existence of the structure and the western part of the pueblo was continually threatened by the river's waters. On each occasion, with levees built to protect the building and a last-minute subsiding of high waters, the church was spared. In 1885 the last grace period expired. The Santa Fe New Mexican Review ran a headline in 1885 exclaiming, "The Raging Rio Grande Is About to Take the Church at Santo Domingo." And then it finally happened: on Thursday, June 3, 1886, the river reached the church and began its destructive undermining. First to go was the main new church, then the old one, and finally the convento. Anything that could be removed had been removed, including all mobile ornamentation, paintings, and other furnishings. The earth structure of the buildings succumbed to the turbulent waters and became part of the riverbed or bank or was carried downstream.

Father Noel Dumarest, a young French priest, was assigned the custody of Santo Domingo on January 1, 1895, as part of his ministry at Peña Blanca. Through his prompting a new church was constructed, this time safely east of the pueblo on rising ground. It maintained the traditional ground-hugging adobe nave with a twin-towered facade, and although a new structure, it immediately occupied a comfortable position in the community. Given the ravages of Archbishop Lamy's campaigns for putting archdiocese architecture in a more "polite" style, it does indeed seem a wonder that the church was built in the usual manner. "Judging from the improvements upstream at San Juan,"

19–5

Santo Domingo, Plan

[Sources: National Park Service Remote Sensing;

and historical photographs]

John Kessell succinctly put it, "one might have expected the new Santo Domingo church to rise with peaked windows, gabled roof, and slender white steeple."[18] Somehow the building escaped this fate. Perhaps Dumarest was in no bargaining position as to style—he was both too young and too new on the job—or maybe the traditional ways of Santo Domingo pueblo forced continuity rather than innovation.[19]

The church of Santo Domingo is rather small in comparison to, say, San Felipe nearby, but the congregation at the time the building occurred was probably smaller. Domínguez listed the population of the village in 1776 as 136 families with 528 persons,[20] and the population had not drastically changed in the intervening century.

The last church, like its predecessors, is a single-naved structure. The choir loft above the entry to the nave continues a spatial sequence that begins between the towers. Because of the building's orientation to the west, the effect of the functioning clerestory is felt only in the afternoon when the declining sun directs its light on the altar. The windows on the south side of the nave, however, somewhat counteract the effect of the limited clerestory light.

The sanctuary is inset, raised, and articulated, but it is not battered inward as at several other pueblo churches. A lively, three-part altarpiece dominates the front of the church and illustrates the continuing tradition of santos in New Mexico. Free and simple, the colors and painting techniques derive their effect from feeling in gesture rather than sophistication in modeling. The lattice altar rail and several other details, like the frames of the reredos, reflect the Victorian penchant for ornamentation, rather than the simple and direct execution of traditional construction.

On the exterior the principal, western facade is composed of two towers with a balcony between, much in the manner of nearby San Felipe or the rebuilt Cochiti. But unlike the earth tones of most of the church, the western elevation is rendered more emphatic by the use of white and color. Painted decorations exhibiting the same feeling as woven patterns are painted over the white background. The large beams that span the opening (in 1982) are colored in green, white, and red; the geometric designs are intricate and handsome and reinforce the presence of the main doorways. A stepped motif integrates the dado wainscot with the frame around the lower and upper balcony doors. Also on the balcony are the two familiar horses that Hesse tried in vain to have eradicated with whitewash (see San Felipe).

One enters the church through the enclosed campo santo at the west of the church. Earthen and bare except for a single wooden cross, the enclosed court marks the collective summation of the hundreds of graves on this site or on that land once west of the pueblo reclaimed by the river.

Writing in 1929, Earle Forrest noted that each year at the fiesta on August 4 the church was put in order: "It is cleaned and whitewashed, and two large horses are painted by native artists on the front [of the church]."[21] The annual dance is still held in August, and it has grown into one of the main attractions of the summer season. Several hundred dancers may participate, and a crowd of thousands fills the pueblo. There is a strange mixture of cultural institutions at this time: the Anglo tourist, often in strange garb; the commercial aspects of the fair; the amusement park rides and snocones; the presence of the faithful at the church; and, of course, the dancers emerging from the kivas clad in costumes that date back centuries. A curious, sometimes tawdry blend, it directly reflects the juxtaposition, or collision, of the cultures and values from which New Mexico has been fashioned.

San Felipe Pueblo:

San Felipe

1605; 1706 (new site); c. 1801

The earthen architecture of a pueblo looks so resolute and wedded to the site that it is difficult to believe that at some time in the past those buildings might not have been there. The structures read as geometric landforms, while the plaza spaces and alleys recall a slightly more confined and formalized version of the canyons that surround the site. Seen from the elevated bank across the river, San Felipe elicits just this feeling: as if it had always been in just this place, in more or less the same form.

But this is not the case. The pueblo has actually been moved at least twice since the time of the Spanish entrance into the province. In 1540 Coronado passed through this land on his move north and found the pueblo at the foot of Tamita Mesa. Some fifty-one years later Castaño de Sosa stopped at the village and christened it San Felipe, overlying its native Keres name of Katishtya. Apparently there is no translation for the name; Hesse, for one, said he had never been able to discover one.[1]

On Oñate's entry into the territory, the various religious personnel were assigned their posts and duties. Fray Cristóbal de Quiñones was assigned to San Felipe, and it was he who supervised the construction of the pueblo's first church, built in 1605. He died two to four years later and was buried inside the mission.[2]

Benavides described San Felipe only as part of his generalized description of the Keres, saying that it probably contained a joint population of "more than four thousand souls, all baptized" and that it possessed three "very spacious and attractive churches and conventos."[3] Some few decades later San Felipe was specifically credited with "350 souls, a good church and the provision for public worship is very well arranged."[4] Like nearby Santo Domingo, it boasted a choir, an organ, and other musical instruments.

After the Pueblo Revolt and the Spanish retreat to El Paso, the San Felipe church fell victim to the whim and revenge of the natives and the elements. When Vargas reentered the province, he found the pueblo relocated on the top of the adjacent mesa, no doubt for protection against both the predictable return of the Spanish and the other hostile Indian groups. Thereafter, a church was built on this elevated site, a small church of stone measuring twenty by fifty-four feet set in the northeast corner of the plaza. Although down to its foundations, and immediately adjacent to the eroded edge of the mesa, the ruins of the church are still visible in a 1967 aerial photograph.

Either Vargas was successful in goading the inhabitants into coming down from their mesa top to

20–1

San Felipe

San Felipe has one of the best-defined plazas of all the pueblos. The church, at the lower left, is long and low, its

walled campo santo enclosing a square courtyard.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

20–2

San Felipe

The ruins of the early church on the mesa are still visible in this aerial

photograph.

[Dick Kent, 1960s]

20–3

San Felipe

1899

A classic example of the two-tower facade type, San Felipe has aged

gracefully in this turn-of-the-century view.

[Adam C. Vroman, Museum of New Mexico]

the more manageable lands along the river, or they realized that the probability of attack by other natives had been greatly reduced with the return of the Spanish. In either case there was no longer any need for living in this defensive and inconvenient position distant from water and fields. And so San Felipe pueblo was moved to its present location, somewhat reversing the migration pattern of the Anasazi at Mesa Verde, as they shifted downward from the mesa into the caves.

The pueblo today is formed around a single, highly defined square and slightly concave plaza that orients to the river to the east. Some time shortly after 1700, probably near 1706, a church was built at the new site south of the pueblo, and here it remains.

Fray Juan Álvarez reported in January 1706 that both the pueblo's residential structures and kivas and the new church "are being built, the latter having been moved down from a high mesa."[5] This early structure proved insufficient for the needs of the community, and a larger church was constructed in 1736 through the efforts of Fray Andrés Zeballos. Little attention, however, was paid to the convento in which he lived, adding, in retrospect, greater commitment to his vows of poverty. In 1743 a Franciscan successor, Fray Pedro Montaño, set to remedy the priest's living conditions, which he found deplorable. Montaño prided himself on the results:

All this [fixing the convento, stables, corrals, all of which were in ruinous condition] I repaired and put in order, raising the walls anew, cleaning out and leveling everything that was uneven and full of sand for the most part, all at a cost of great diligence and care, and labor in order to incline the Indians. I stayed with them in person like a shadow, not even giving them the time to go and eat, so that they might not get away and quit their labor.[6]

Kubler specified that roof repairs directed by Andrés Zeballos were undertaken in 1736 and involved "the use of 84 canales or drain spouts, probably signifying a church of some size."[7]

Tamarón passed by in 1760 but offered no description of San Felipe; he seemed intent on getting on to Santo Domingo. Domínguez, however, with his usual thoroughness, left a complete description of the church, convento, and pueblo:

The church is adobe with thick walls, single-naved, with the outlook and main door to the east. . . . The sanctuary is marked off by four steps made of wrought beams. . . . It is as wide as the nave and as much higher as the clerestory demands. The choir loft is in the usual place and like those of the mis-

20–4

San Felipe

circa 1935

Exposed to erosion in four sides, the pillars of the towers appear badly worn. Note also the geometric painted

ornament around the doors and the carved and overscaled corbels supporting the roof of the balcony.

[T. Harmon Parkhurst, Museum of New Mexico]

20–5

San Felipe

1919

The attenuated length of the nave about which Domínguez commented late in the eighteenth century is apparent

when viewed from the flank.

[Museum of New Mexico]

sions that have them. Its entrance is from the flat roof of the convento. On the right side there are three poor windows with wooden gratings which face south.[8]

There was no covering on the floor: "It was bare earth, its interior dark."[9] There were at the time ninety-five Indian families with 406 persons living in the pueblo.[10]

Shortly after 1801 Fray José Pedro Rubí de Celis assumed the administration of the mission. Writing in 1808, he noted that "the church was rebuilt with its two new towers,"[11] implying that until that time there had been only the planar facade typical of early postrevolt religious building. In 1782 the status of the church was reduced to that of a visita of nearby Santo Domingo. The control of the church was removed from the hands of the Franciscans in 1823 as the missions were secularized by the Mexican government; but on July 9, 1900, the Franciscans returned to the pueblo, serving San Felipe from nearby Peña Blanca.

Father Jerome Hesse left us with a somewhat ironic and amusing incident of life in San Felipe pueblo and the Indian's relation to the church. It tells of Christmas 1912 and poignantly illustrates the amalgam of native and Christian beliefs at this most sacred of holidays. Like the Christmas story of Isleta by Elsie Parsons (see Isleta), the anecdote also illustrates the relationship between architecture and dance, structure and movement, and prayer and belief. Father Jerome wrote, "I entered the church where I found the altar tastefully decorated. Before the altar the Indians had erected a hut of cedar twigs, covered with a roof of straw." (This was similar to structures built outdoors to house a shrine or serve other religious purposes—for example, the structures built each year as part of the dance on August 4 at Santo Domingo pueblo, erected at the head of the principal dance plaza.)

A dance? in church? before the crib? What a scandal, a desecration, a sacrilege! someone might say. And the benches? Are they removed? Well, there are no benches. . . . The Indians squat on the floor, not even a wood floor, but just Mother Earth. The interior of an Indian church is very bare, at least at San Felipe and Santo Domingo. Four adobe walls, whitewashed within, an adobe roof, generally leaking in places, with an adobe floor: truly not unlike the stable of Bethlehem. A few simple boards nailed together to form an altar, a statue of St. Philip, a few mural paintings to serve as ornaments, and you have a complete Indian church.[12]

If decoration was spare at San Felipe, segments of the church were whitewashed, but whitewashing

20–6

San Felipe, Plan

[Sources: National Park Service Remote Sensing;

and historical photos]

was usually restricted to that segment of the principal facade between the towers or to a wainscot on the interior, while the balance of the church remained the color of the earth. A similar practice is still evident at Picuris, where only the facade is painted white, although the balance of the structure is an earthen color. At Laguna the entirety is white, although it was probably not always so. The whiteness makes a lasting impression in the dusty lands of New Mexico as almost every structure, whether made of earth or not, acquires a chromatic layer of dust that joins it to the countryside.

Although the towers were eroding in 1915, Prince was nonetheless impressed by the brilliance of San Felipe and noted its "dazzlingly white appearance"; he also remarked that "it is cared for most faithfully, being whitened every year until it glistens in the bright sunlight."[13] There were other benefits to whitewashing, which Hesse described in a 1920 article. Hesse was troubled by the two horses painted on the upper balcony of the eastern facade, a motif also present at Santo Domingo and occasionally at other churches. "Horses, stationed at the entrance of a church," he reasoned,

are not very conductive to devotion, so I asked the parishioners to obliterate them through a coat of whitewash. The feast of St. Philip, patron of San Felipe, was near at hand, when, according to "costumbre" (custom) the church is annually whitewashed both inside and outside. The Indians' love for the horse is well known; and "cabellitos" are objects of their superstitious veneration. . . . What happened? The church was simply not whitewashed, for the Indians had no time! Excuses are never wanting to the Indian.[14]

The church of San Felipe is an impressive structure but is more impressive from the flank than from the front. The facades of the Spanish mission churches, other than those of the Salinas district and perhaps Acoma, rarely achieve the scale or proportions necessary for lifting them from their bases. Nor are they integrated into the pueblo in such a way that their increased mass is sufficient to create a striking contrast. In pueblos such as Zia or Laguna, for example, when the pueblo is contemplated as a unit, the church may actually read more strongly from a distance. In these conditions the church, a reflection of native construction method, becomes a part of the architecture of the pueblo, however different the form.

Height was not the means, nor was span the tool to increase the church's volume, and the heights of postrevolt churches rarely exceeded their widths. Length was the sole variable, and with it the church size, determined by the number of the congregation. San Felipe is nearly one hundred twenty feet long, an exceptional dimension for an architectural method that historically had produced living spaces on the order of twelve to fifteen feet square.

As Kessell noted, there are more vigas in place today than at the time of the Domínguez visit, suggesting that the church was extended during the 1801 remodeling, at which time the twin towers were added to the facade.[15] The marvelous photograph taken in August 1919 from the southwest, where the nave is played against the lower convento to the south, illustrates the feel of the long, literally shiplike nave and the characteristic bump of the tapered apse as it rises to accommodate the transverse clerestory. This photo also shows the seriously eroded towers, particularly the pinnacles of the open belfries, which suffered under rain and wind from all four directions. The church was refurbished after 1920, probably on more than one occasion, as it usually appears in good condition in photos.

The images of the horses that troubled Father Jerome still grace the entry facades, although they were missing from a Parkhurst photograph from the 1930s. By that time the convento had all but melted into the landscape, and a small structure (baptistry/sacristy) appended the nave to the north.

With the importation of commercial paints came a greater palette of colors. Today the facade and its wooden brackets are painted in lively hues: turquoise tipped with red. The horses have returned, and the dado and stepped sky altar motif of the wainscot are worked in yellow. Even from the opposite bank of the Rio Grande, the church creates an unmistakable impact.

Zia Pueblo:

Nuestra Señora de la Asunción

1610–1628?; 1693

The mission church of Nuestra Señora de la Asunción at Zia rests on its mesa like a lion in its lair and looks eastward. Like Laguna, the church's golden white form contrasts markedly with the surrounding earthen colors of the pueblo, and also like Laguna, its visual primacy within the pueblo is assured by position and scale. The Espejo expedition reached Zia and found five towns in Cumanes province. Zia was the principal settlement, "having eight plazas or market places, and houses plastered or painted in many colors."[1] The pueblo occupied a site along the Jemez River and was built on the ruins of an earlier village. The houses, unlike those of most other pueblos, integrated basalt rock with the adobe mud, thereby replacing construction of purely adobe brick. The Indians were cautious and kindly to the strangers, at least initially, and provided them with provisions and even cotton mantas (blankets).

Under Oñate's pressure, the pueblo swore allegiance to the Spanish crown and the Catholic church at a meeting held at the Santo Domingo pueblo in July 1598. Fray Alonso de Lugo was placed in charge of Zia in 1598, and the first church followed soon thereafter. The convent was first mentioned in July 1613 and was probably founded by Fray Cristóbal de Quirós in 1610. Although the mission of San José de Giusewa maintained its own resident priest until its demise circa 1630, Santa Ana remained a visita of Zia and had been as early as 1614. Benavides mentioned seven churches in the province; Prince assumed that at least three of them must have been Jemez, Santa Ana, and Zia.[2] Then came the revolt of 1680 and the supposed ruin of the church.

In 1687 Governor Domingo de Cruzate, in an abortive attempt to retake New Mexico, attacked the pueblo in what was to be one of the bloodiest battles between the Spanish and the Indians.[3] Even allowing for inflation of numbers, the Indian losses must have been considerable. Cruzate claimed that about six hundred Indians were killed and that the seventy remaining were sentenced to ten years of slavery, "except for a few old men who were shot in the plaza."[4] It is no surprise that the villagers, recalling the horror of those previous few years, submitted peacefully to Vargas and agreed to rebuild the church. A large cross was erected in the main plaza, the stone base of which remains to this day.

When the mission was first established in 1598, it was dedicated to San Pedro and San Pablo. When the church was refounded in 1692, its attribution was changed to Nuestra Señora de la Asunción. Vargas found the church in the normal postrebel-

21–1

Zia Pueblo

The church and pueblo from the air.

[Dick Kent. 1960s]

21–2

Nuestra Señora de la Asunción

1923

From the north the church—low and heavy—appears almost as a

geological formation.

[Odd Halseth, Museum of New Mexico]

21–3

Nuestra Señora de la Asunción,

Plan

[Source: Kubler, The Religious

Architecture ]

lion condition: the roof and wooden elements were burned or destroyed, as were portions of the walls. But this symbolic desecration of sacred structures seemed to have satisfied the Indians in almost all instances, and pragmatically inclined, they used the four enclosing walls as corrals or cattle pens.

In the case of the Zia, however, the natives were not occupying the same site at the time of the Reconquest but had shifted some ten miles or so away from the old pueblo. Vargas wrote, "I ordered them to reoccupy their said pueblo, since the walls are strong and in good condition and also the nave and main altar of the church are in good condition, only lacking the wooden parts, which I ordered them to cut at the time of the next moon." Vargas promised them a saw, "so that they would be able to cut the said wood for the church and convent."[5] The church was rebuilt, and in its current form dates from this time to near the end of the seventeenth century.[6] Custos Juan Álvarez noted in 1706 that the church building "is now at a good height,"[7] which suggests that the rebuilding had not proceeded as quickly as Vargas had predicted or that, following the typical cycle, after a few years of neglect the church structure was once again in need of repairs.

John Kessell quoted at length Fray Manuel Bermejo, who, writing in 1750, claimed credit for another major rebuilding effort: "[I worked] personally with the Indians, without the help of said gentlemen [government officials], as I am doing at present on the church that I have begun from the foundation up and on the repair of the convento which was falling in ruins."[8] In all probability this did not extend to the actual reconstruction of the church from the foundations up but constituted only extensive reparation. (If Bermejo was dealing with the adobe erosion known as coving, in which the edge of the structure at the ground was undermined by splashing and undercutting, he would have indeed been working from the ground up.)

In 1760 the weary Bishop Tamarón made no comment on the church, merely saying that Zia "is two long leagues from Santa Ana over dunes and sandy places."[9] The 1750 census showed that there were about five hundred inhabitants in Zia, a considerable decline from its pre-European days of the village with eight plazas. As usual, it was Domínguez who provided the first really detailed description of the church:

The church is adobe with very thick walls with the door to the east. . . . The sanctuary is marked off by two steps made of wrought beams and from there to the center it measures 6 varas, being as wide as the

nave and as much higher as the clerestory demands. Choir loft like those mentioned before. It has four windows with wooden gratings on the Gospel wall, facing south, and one in the choir. The nave is roofed with forty good corbeled beams, and the clerestory rises along the length of the one facing the sanctuary, whose roof consists of eight beams like the foregoing.[10]

Domínguez credited Fray Francisco Xavier Dávila with the rebuilding of the church. Dávila was in residence at Zia during part of the 1750s and early 1760s and may have been responsible for yet another rebuilding effort.[11]

The convento was meager and basic, as were its furnishings.[12] In 1806 the church and its possessions were inventoried by Fray Mariano José Sánchez Vergara. He specifically noted an altarpiece commissioned in 1798 by Víctor Sandoval and Dona María Manuela and ascribed to the same santero who painted the reredos at Laguna (hence called the Laguna Santero): "This is all that this church possesses, and everything is in need of repair. To do so there are no settlers and funds to tap. Unless some measure is taken for this purpose nothing will improve."[13] Nothing ever improved in the battle against time and the elements, and the particularly annoying problem of the roof parapet meant that the outcome could be a stalemate at best. From the day of its completion, the church began to deteriorate, sometimes at an alarming rate.

Lieutenant Bourke, on the scene in 1881, also included Zia in his rounds. Matter-of-factly he stated, "Front of ruined church of the Virgin. . . . Interior going rapidly to decay. . . . The ceiling is riven pine slabs, and according to Jesus (son of the pueblo governor), is "muy viejo" (very old). The nave measured from the floor of the altar to the main door is 37 paces in length. Earthen ollas [ceramic jugs] are in position as holy water fonts."[14] By this time the church's roof had been lowered and the nave shortened (in comparison to Domínguez's description). The balconied facade might have been the result of rebuilding undertaken at this time.

Bourke was less kindly with his evaluation and verdict: "Interior rapidly going to decay. . . . The wooden figure of the Savior on the Cross must have been intended to convey to the minds of the simple natives the idea that our Lord had been butchered by Apaches. If so, the artist had done his work well."[15] Americans rarely took kindly to Hispanic-Indian imagery, whether to the "barbarity" of the designs at Cochiti that Prince cited or the not-infrequent comments about the "gory dolls" that filled the various altars.

21–4

Nuestra Señora de la Asunción

1923

The unrestored Neo-Gothic altarpiece shines under the roof light.

[Odd Halseth, Museum of New Mexico]

21–5

Nuestra Señora de la Asunción

1923

The choir loft (east) end at the time of the 1920s restoration.

[Odd Halseth, Museum of New Mexico]

Bandelier, in his Final Report of 1888, wrote, "The church is large and the outer walls are asserted to be those of the church prior to 1680, the new walls being built inside of them. The appearance justified the presumption of old age. And in his Journals , he noted, "The site may be the same but the church is probably a more recent edifice though erected on old foundations."[16] This remains the commonly accepted explanation except that the extent of the prerebellion walling has not been precisely determined. There is a double thickness of wall apparent on the south wall, however. Kessell offered the traditional story that the vigas for the roof had been cut too short.[17] Rather than return to the mountains and recut, rehaul, and reseason the timber, the builders added an additional thickness of wall within the old one, thereby rendering the spans of the vigas sufficiently long.

There was no priest in residence in 1881. From 1890 on Zia was served from Jemez, giving testimony to the fact that the importance and the population of the pueblo had both declined, at least in the eyes of the church.