V

If, as Francis Davison (1602) claims, some critics can insist that poetry too "doth intoxicate the brain, and make men utterly unfit, either for more serious studies, or for any active course of life" (Poetical Rhapsody , 4-5), a commendatory epigram to Sir John Beau-mont's Metamorphosis of Tabacco (1602) can defend Beaumont by comparing his poetry to tobacco's self-consuming influence:

TO THE WHITE READER

Take up these lines Tobacco-like unto thy brain,

And that divinely toucht, puff out the smoke again.

( Poems , 272)

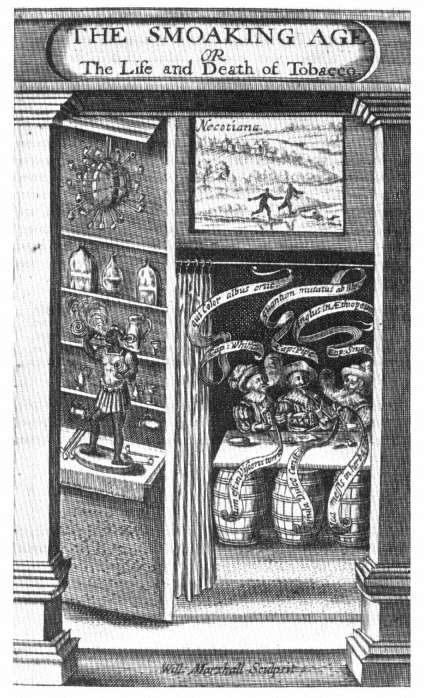

Figure 6.

Frontispiece to The Smoaking Age , by Richard Brathwait, London, 1617. The

upper scrolls read "Qui Color albus erat. / quantum mutatus ab illo. / Anglus in

Æthiopium " (whose color was white. / how much changed from that. / an Englishman

into an Ethiopian). (By permission of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.)

Beaumont himself quickly implies that the primary metamorphosis of his title is tobacco's transformation into his poetry, a transformation unabashedly evoking the savage practice Monardes describes and Philaretes abhors:

But thou great god of Indian melody

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

By whom the Indian priests inspired be,

When they presage in barbarous poetry:

Infume my brain, make my soul's powers subtle,

Give nimble cadence to my harsher style;

Inspire me with thy flame, which doth excel

The purest streams of the Castalian well.

(276-77)

Where Marbecke tries to reconcile savage to Christian value, Beaumont characteristically insists on celebrating those features of Indian smoking, the superstition and barbarity, that most stand in the way of such a reconciliation. Beaumont's dedicatory poem to Drayton had warned readers that Beaumont would prove irreverent, since it emphasizes that the dedication is meant to be as much an affront to the powerful as a compliment to a friend: Beaumont claims he "loathes to adorn the triumphs of those men, / Which hold the reins of fortune, and the times." The Latin tag ending the dedication, from Catullus's dedication of his own work, embraces the poet's professed marginality less militantly, joking now about Beaumont's intellectual poverty: to whom better should I dedicate my poem, asks Beaumont, namquam tu solebas / Meas esse aliquid putare nugas , than you who used to think my trifles something. Yet with the rigor of a puritanical antagonist, Beaumont in his invocation completes the traditional assault on fruitless poetry by allying his poem not only with poverty and inanity but with superstition. For Beaumont subscribes to an alternative—in his view Spenserian—system of "estimation," whose genius is "the sweet and sole delight of mortal men, / The cornu-copia of all earthly pleasure" (275).66 If poetry's influential critic Henry Cornelius Agrippa declares that poets super fumo machinari omnia (Eiv), or, in the Elizabethan version, "devise all things upon a matter of nothing [fumo , smoke]" (33), then Beaumont will celebrate the "Castalian well" of fumo —tobacco.

After its invocation, in fact, the poem embarks on two myths of

tobacco's creation that celebrate tobacco's worth as against the religious and temporal orthodoxy separately scorned in dedication and invocation but now combined in the figures of the Olympian gods. In the first myth, Earth and her subjects frustrate their oppressor, Jove, by enlivening Prometheus's subversive creation, man, with the flame of tobacco (Beaumont, Poems , 277-86). In the second, less contentious tale, Jove courts a beautiful but standoffish American nymph who outshines Apollo; Juno angrily transforms her into a plant—tobacco; but Jove retaliates by further metamorphosing his former love into "a micro-cosm of good" (286-304). While both myths associate tobacco's value with the victimized and profane, one last account of tobacco moves closer to conformity, though only in order to attack still another kind of tyranny. This account takes the premise of the second myth further, and decides that the gods must always have been ignorant of tobacco, or else, "had they known this smoke's delicious smack, / The vault of heav'n ere this time had been black" (304). The more the Olympians are imagined as prone to love "the pure distillation of the Earth" (304), the more their powers and authority are blotted out, blackened; for their love of tobacco assimilates them to Harriot's Indian gods, and by implication, the pagan Greeks and Romans to the pagan Indians.67 In other words, Beaumont involves tobacco in a rebellion now against not only religious or temporal authority but also "the purest stream of the Castalian well," the authority of the classics. Even the gods' ignorance of tobacco damns the classical world, by reminding Beaumont's readers of one of the first and most powerful intellectual reactions to America's discovery, the realization that the ancients had, for all their intimidating genius, proven profoundly benighted—"Had but the old heroic spirits known" (305)!68

Yet Beaumont does not want the subversion of one orthodoxy to become a triumph for another: he now explicitly asserts that those "blinder ages" (306) were indeed wrong to worship Ceres, for instance, but only because they ought to have worshipped tobacco instead. Modem times, he claims, have not abandoned superstition but discovered improvements on it:

Blest age, wherein the Indian sun had shin'd,

Whereby all Arts, all tongues have been refin'd:

Learning, long buried in the dark abysm—

Of dunstical and monkish barbarism,

When once the herb by careful pains was found,

Sprung up like Cadmus' followers from the ground,

Which Muses visitation bindeth us

More to great Cortez, and Vespucius,

Than to our witty More's immortal name,

To Valla, or the learned Rott'rodame.

(314-15)

To keep his distance from both orthodoxy and superstition, Beaumont now orthodoxly eschews papist superstition, "dunstical and monkish barbarism," yet in the name neither of humanism nor of the true church but of tobacco.

This last profanity derives a special bite from the fact that, to many of Beaumont's readers, the distinction between Indian and papist paganism would have seemed a nice one indeed. We have already seen how Marlowe conflates the two kinds of "ceremonial reverence" (and apparently some Catholic priests overseas felt the same temptation: in 1588 the Roman College of Cardinals was forced to declare "forbidden under penalty of eternal damnation for priests, about to administer the sacraments, either to take the smoke of sayri , or tobacco, into the mouth, or the powder of tobacco into the nose, even under the guise of medicine, before the service of the Mass"69 ). Chapman's Monsieur D'Olive mocks the similar views of Marlowe's enemies—here, a Puritan weaver reviling tobacco:

Said 'twas a pagan plant, a profane weed,

And a most sinful smoke, that had no warrant

Out of the Word; invented sure by Satan

In these our latter days to cast a mist

Before men's eyes that they might not behold

The grossness of old superstition

Which is, as 'twere, deriv'd into the Church

From the foul sink of Romish popery.

( Monsieur D'Olive 2.2.199-206)

The difference for Beaumont seems to be one of proximity: England has just escaped papistry's "dark abysm," while Indian superstition is at once too distant and too primitive a threat to be

taken seriously. The superior status of a blest age freed from papist barbarism now leads Beaumont to affirm that

Had the Castalian Muses known the place

Which this Ambrosia did with honor grace,

They would have left Parnassus long ago,

And chang'd their Phocis for Wingandekoe.

( Poems , 315)

The wit of the final line depends on perceiving the two place names, one Greek and one Indian, as equally outlandish and barbaric—on the suggestion, again, that the ancients were no better than the Indians, or still more wishfully, that the authority of the classics, as of the Indian "people void of sense" (315), depends on the playful attribution of that authority by the enlightened English reader.

One might say that the comical mixture of classical with Indian subject matter focuses power on England as the excluded middle,70 whose perfect representative would now seem to be "our more glorious Nymph" (315), the virgin more successful than tobacco in withstanding the encroachments of the powers that be, of superstition East and West—that "heretical" authority, Elizabeth. Earlier in the poem Elizabeth had already enabled Beaumont to make a provisional act of obeisance to the status quo: he had claimed that, just as tobacco has replaced Ceres in the heaven of the superstitious, so Elizabeth has replaced tobacco. Wingandekoe, the American home of the tobaccoan nymph, "now a far more glorious name doth bear / Since a more beauteous nymph was worshipt there": as Beaumont's note explains, "Wingandekoe is a country in the North part of America, called by the Queen, Virginia" (286-87). The moral would seem to be that Elizabeth outshines the dreams of the superstitious pagan; modem historians of Elizabeth's cult would conclude that Beaumont wants to substitute worship of the queen for the cast-off "superstitions" not just of paganism but of papistry, so that Elizabeth can absorb Catholicism's displaced authority.71 Yet here Elizabeth does not stand apart, virginal, from the superstition whose authority she absorbs. The terms of praise for Elizabeth that follow—the queen is, for example, "our modem Muse, / Which light and life doth to the North infuse," "In whose respect the Muses barb'rous are, / The

Graces rude, nor is the phoenix rare"—sound if anything indistinguishable from the ones Beaumont previously applied to tobacco; in his poem at least, Elizabeth's authority, like the poem's itself, depends on highlighting its inseparability from overt superstition.72 The comparison of queen to poet helps clarify the distinction: just as Beaumont refuses to name his own religion outright and instead presents his sophistication only negatively, masquerading as Indian or ancient barbarism, so Elizabeth's accomplishments are defined only negatively, by the degree to which she does tobacco or ancient Muse one better, and so, as Beaumont says, "exceeds her predecessors' facts." Beaumont nicely captures the paradox of Elizabeth's alliance to and difference from superstition when he asserts, "Nor are her wondrous acts, now wondrous acts" (315).

Such definition by negation may seem a little more explicable in an overseas context, as "the improvisation of power,"73 when the English want the natives to love them and yet still to look foolish. Raleigh's lieutenant Keymis (1596) reports how, on his return to Guiana the year after Raleigh's visit, he found the natives constant in the devotion Raleigh taught them:

Thus they sit talking, and taking Tobacco some two hours, and until their pipes be all spent . . . no man must interrupt . . .: for this is their religion, and prayers, which they now celebrated, keeping a precise fast one whole day, in honor of the great Princess of the North, their Patroness and defender.74

Of course, Catholic polemicists could ignore the distinction between the savage and civilized estimation of Elizabeth as easily as antitobaccoans ignored the distinction between savage and civilized smoking.75 But leaving aside this problem, as well as the question of how deeply committed the Indians actually were to the queen, what practical benefits could Beaumont have thought that this Indian chapter of the cult of Elizabeth had yielded England? The purpose behind Beaumont's own version of the cult seems obscurer still when the one act of Elizabeth upon which Beaumont decides to elaborate is perhaps the most dubious one he could have chosen: he extols the queen for having

uncontroll'd stretcht out her mighty hand

Over Virginia and the New-found-land,

And spread the colors of our English Rose

In the far countries where Tobacco grows,

And tam'd the savage nations of the West,

Which of this jewel were in vain possest.

( Poems , 316)

The last anyone had seen of England's single New World tamer at the time, the 1587 Roanoke colony, was more than fourteen years before, and the law presumed missing persons dead after seven; John Gerard's Herball (1597) musters as bright an optimism about the Lost Colony as could be expected when he mentions "Virginia . . . where are dwelling at this present Englishmen, if neither untimely death by murdering, or pestilence, corrupt air, bloody fluxes, or some other mortal sickness hath not destroyed them" (quoted in Quinn, England , 444). As the poem now turns to more strictly imperialist talk, Beaumont himself contradictorily emphasizes the hardships that still await English New World enterprises. Jove, he now says, hates tobacco "as the gainsayer of eternal fate," and so "this precious gem / Is thus beset with beasts, and kept by them"; besides, "a thousand dangers circle round / Whatever good within this world is found," and not the least of the dangers England continues to face are the Spanish, "far more savage than the Savages," who indeed "have the royalty / Where glorious gold, and rich Tobacco be" (Poems , 316-17). Beside the possibly apocryphal exportation of Elizabeth-idolatry to a small tribe in Guiana, then, the "acts" to which Beaumont must be pointing when he claims that Elizabeth has already tamed America are presumably speech acts such as Elizabeth renaming Wingandekoe Virginia, Hakluyt calling Virginia Raleigh's Elizabeth-like bride, Spenser placing Belphoebe in a tobacco field, and Beaumont himself writing this poem: in other words, the importation of barbarism, and especially of its representative "jewel," tobacco, into civilized discourse.

Again symbolic returns from the New World seem almost preferable to something more substantial, and again this preference gets elaborated, in the poem's climax, as esteeming tobacco more than gold:

For this our praised plant on high doth soar,

Above the baser dross of earthly ore,

Like the brave spirit and ambitious mind,

Whose eaglet's eyes the sunbeams cannot blind;

Nor can the clog of poverty depress

Such souls in base and native lowliness,

But proudly scorning to behold the Earth,

They leap at crowns, and reach above their birth.

(317-18)

The sentiment, the contemning of mere fortune, is the same one introduced in the dedication to Drayton, but now oddly transformed from an antipolitical and individualistic pose to a national, imperialist argument: tobacco is the key to England's late and unlikely imperial hopes, "the gainsayer of eternal fate," precisely because it signals that the Spanish "have the royalty" of both it and gold, while the English have no empire at all. Both Beaumont's surprising metamorphosis and his peculiar theory here follow logically, however, from his disdain for those worldlings who, like Daniel's Philocosmus, declare of "trifling" poetry, "other delights than these, other desires / This wiser profit-seeking age requires" (Musophilus , ll. 12-13). Indeed, what in a contemporary work, the last of the Parnassus plays (1601-2), represents a poet's lament about contemptuous patrons, would in Beaumont's poem constitute a patriotic brag: "We have the words, they the possession have." (At one point in the plays another poet even imagines this envied "possession" to be "the gold of India"; as Dekker [1603] says, "Alack that the West Indies stand so far from Universities!")76 Like the Virginia of Harriot and Hakluyt, poetry for Beaumont cannot please the material-minded; and by the same token Virginia requires "the brave spirit and ambitious mind" of the man professionally equipped to see the substance in what appears substanceless—the poet: "For verses are unto them food, / Lies are to these both gold and good" (Agrippa, Vanitie , 33).

But what inspiration is to be had from one's total outflanking by the enemy? A standard Christian explanation of the value of such trouble—here Calvin's explanation, in the chapter where he notes that "man's life is like a smoke"—seems at first miles apart from Beaumont's probable response: "For, because God knoweth well how much we be by nature inclined to the beastly love of this world, he useth a most fit mean to draw us back, and to shake off our sluggishness, that we should not stick too fast in that love" (Institution , 167v). But in justifying the imperial difficulties for

which tobacco stands, Beaumont simply adjusts the sights Calvin sets. Gold has tricked the Spanish into making the literalizing, bestializing mistake of filling their bellies, while tobacco teaches the English instead a limited form of contemptus : "the clog of poverty" that tobacco represents—in short, England's limitation to its island home—does not "depress" Englishmen in their "base and native lowliness" because that clog is made of smoke (and imported smoke at that). Poor Englishmen harness the rarefying power of Apollo, the poet's god, and create a new golden age, not by embracing as the Spanish do the "terrestrial sun" of gold but by attaching themselves to something as nearly nothing as possible.

It is crucial to remember here, however, that in rejecting any binding, material correlative to its powers, the ambitious mind does not appeal instead to a heavenly correlative; though the idea of leaping at crowns and reaching above one's birth certainly suggests an aspiration, in spite of original sin, for a heavenly crown, tobacco smoke does not ascend that high: true, "our sweet herb all earthly dross doth hate, / Though in the Earth both nourisht and create," but when it "leaves this low orb, and labors to aspire," it ends up only "mixing her vapors with the airy clouds" (Beaumont, Poems , 318), which then drop "celestial show'rs" on English heads. Beaumont wants a crown somewhere between earth and heaven, both off the ground and of it, distinguished only from the frivolous low superstition that negatively defines its purview. Tobacco's limited, homeopathic dose of contemptus , its minor and embraceable conflagration, cures the pangs both of worldly trouble and of contemptus itself; it helps the ambitious mind, aware now of its own unfading substance, come to itself.

An alternative explanation of Beaumont's resistance to articulating his theology more clearly would note his multiple convictions for recusancy a few years later (Sell, Beaumont , 8-10), which raise the question whether any other tobacco advocate actually holds Beaumont's possibly anomalous position. It has not been my intention to demonstrate, however, that the writers I have discussed hold any one position about tobacco at all. Rather, they share assumptions about tobacco that are based on earlier physiological, economic, poetic, and theological claims, claims that are themselves analogous and cohere around premises concerning England the island, limited, rheumatic, and late; the analogies may or may

not be pursued, or the writer may or may not recognize the consequences of those analogies he does pursue. Indeed, the primary value of tobacco for these writers is precisely its negativity, which enables it to mediate between normally opposed terms—between purging and feeding, high and low, trifle and jewel, superstition and religion, home and away, heaven and earth—by displacing both terms and substituting its own neither material nor spiritual essence, its "sweet substantial fume," instead.77 The negativity of Beaumont's theological argument, for instance, substituting tobacco worship for either Protestant or Catholic polemic, may suit both his rebelliousness and his fears about recusancy convictions; but its efficacy, or danger, does not stop there. How does the imperialist reconcile his earthly ambitions to his heavenly ones? Beaumont's tobacco argument avoids choosing between worldly and otherworldly treasures by shadowing his aims in smoke.

Tobacco's critics perceive this shadowy negativity simply as negation, a problem to which Beaumont himself draws attention when at the end of his poem (in lines reminiscent of the end of The Shepheardes Calender ) he asks his Muse, now suspiciously "clok'd with vapors of a dusky hue," to "bid both the world and thy sweet herb, Adieu": the poem too goes up (or down?) in smoke. But then the poem's motto, Lusimus, Octave, &c ., from Virgil's Culex —in Spenser's translation, "We now have played (Augustus) wantonly"78 has already cast this apparently wanton and excessive use of tobacco as itself dispensable, a mere fledgling poetic attempt soon to be transcended by a more properly imperial invention: for Beaumont, the tobacco pipe simply tunes the modern pastoral. Later, after England and the newly created Virginia Company had begun to pursue Beaumont's imperial goal more assiduously, Virginia's colonists tried to make the same argument about their own tobacco craze. Deploring the idea of a settlement based on a commodity that would "vanish into smoke" (in fumu . . . evanitio ), John Pory (1620) asserts that "the extreme Care, diligence, and labor spent about it [tobacco], doth prepare our people for some more excellent subject."79 "We affect not that Contemptible weed as an end," an official letter from the colony (1624) de-dares, "but as a present means" (McIlwaine, Journals , 26). My next chapter will show, however, that, long after Raleigh's early failures in Virginia, "contemptible" trifles like the conveniently re-

placing and replaceable tobacco refused to fade from colonialist view. In fact, it was only after all other plans for Jacobean Virginia seemed to its critics "vanished into smoke (that is to say into Tobacco)" (Kingsbury, Records 4:145) that the colony finally became profitable; the credulous savage so long anticipated by English colonialists, the one who was to buy trifles for gold and thus save the colony, turned out to be the English smoker.80 By 1624, even James had to admit that Virginia "can only subsist at present by its tobacco" (CSP Dom . 11:290); and indeed, the more dependent on tobacco Jamestown became, the more ambiguous became even James's distaste. In 1619 the College of Physicians declared homegrown tobacco unhealthy, and James banned its production; but his derision turned on more than medical considerations: in exchange for the ban, the Virginia Company allowed the Crown much higher duties on the company's tobacco imports.81 The colony that was supposed to expand the English economy by providing England the goods it could otherwise obtain only "at the courtesy of other Princes, under the burthen of great Customs, and heavy impositions,"82 had been transformed by James, then, into simply one more foreign peddler of trifles, with James its extortionist lord—a king not of Fairyland but of thin air.83