Male Religious

Nuns might be believers or disbelievers, supplicants or sister seers of the visionaries. Male religious could also be spiritual directors to the seers or expert examiners of visions. Some clergymen, like Padre Burguera himself, thus had a professional as well as a personal interest in the apparitions.

From their junior seminary just over the hill in Gabiria, Passionist professors and students could hear the hymn singing and prayers at Ezkioga and they were inevitably embroiled. The Passionist order, founded in Italy in the eighteenth century, had established its first house in Spain in Bilbao in 1880. In 1931 the north was still its stronghold. In the first weeks of general excitement at Ezkioga the Passionists were "almost all in favor." Some individuals converted at Ezkioga went to confess at the Passionist seminary. On 1 August 1931 two fathers were said to have seen one of Patxi's "levitations." The seers tapped into Passionist interests with visions of the Passionist Gabriele dell'Addolorata and the would-be Passionist, Gemma Galgani. The Ezkioga farmer Ignacio Galdós had a vision of a Passionist preaching to more than four thousand people; in the vision a star fell from the sky until it was by the side of the preacher, who distributed parts among the crowd. Two-thirds of the people disappeared into the darkness, while the remainder, brilliantly lit, fell to their knees; the Passionist blessed them with his cross.[54]

For Gabiria, Antonio M. Artola with Joseba Zulaika, Bilbao-Deusto, September 1982, p. 4. For life at the school, Ecos de San Felicísmo, 1932, pp. 197-199, 230-233, and Artola, Martín Elorza, 16-31. Initial Passionist enthusiasm: Basilio Iraola Zabala (b. 1908), Irun, 17 August 1982, p. 1, who said his first mass in Gabiria in 1931, and Dositeo Alday, Ramón Oyarzabal, and Rafael Beloqui, Urretxu, 15 August 1982; confessions, B 51; for Patxi's "levitations," Elías, CC, 21 August 1931; for Gabriele dell'Addolorata, ARB 33-34; for I. Galdós, B 755.

The initial enthusiasm of the Passionists is understandable given their devotional aesthetic. Passionists had accompanied their sodalities to the visions of the Christ in Anguish at Limpias, a kind of throwback to the Baroque devotions of Holy Week that declined in the north in the nineteenth century. This kind of devotion has revived in part because of parish missions. In their missions the Passionists set up outdoor stages. A parish priest in Navarra commented on their "special method":

preaching from a stage or platform in an appropriate place and giving a brief talk on one aspect of the Passion of Our Saviour after the principal sermons; they did the apparition or entrance of the Most Holy Virgin, the descent from the Cross, and the procession of the holy burial.

The visions at Ezkioga also had as their central metaphor the Passions of Christ and the Virgin, and Patxi's similar stages at Ezkioga served the same purpose, the provocation of remorse by a kind of sacred theater. The order's magazine, El Pasionario , carried almost no news of the apparitions, but issues published before the visions started included depictions of the Passion in poses much like those later struck by the Ezkioga seers and descriptions of the mystic life of the German stigmatic Thérèse Neumann. The magazine was read in the villages and towns around Ezkioga.[55]

For mission, Venancio Jáuregui, "En Goizueta," BOEP, 1916, p. 154. Basilio de San Pablo, "Manifestaciones de la Pasión." Luistar was the distributor of El Pasionario in Albiztur. Another Passionist magazine, Ecos de San Felicísimo, printed a report on the visions on 1 September 1931.

After the exposé of Ramona's miracle, most of the Passionists turned against the visions. Indeed, some, like Basilio Iraola, a friend of the Ezkioga pastor, were opposed from the start. But a few remained firm in their belief. I spoke in 1982 to Brother Rafael Beloqui, who said he had been to the visions thirty-nine times, primarily because he enjoyed the praying so much. In June 1933 a certain Padre Marcelino, based in Villanañe (Alava) and Deusto, was thrown from a horse when returning from a remote village where he had celebrated mass. A rural doctor told him he was in critical condition, and after his condition worsened he said he saw the Virgin who told him he would recover. He attributed the cure to the Virgin of Ezkioga. Rumors like this and one that a Passionist had seen Gemma and San Gabriele at the site gave the believers hope that the order would be on their side.[56]

B 739-740. After the war a few Passionists still believed in the visions; see Beaga, "O locos o endemoniados."

In the first flush of enthusiasm in the summer of 1931 Franciscans, Capuchins, Claretians, and Dominicans went to the vision site and published their impressions, which varied from noncommittal to guardedly enthusiastic. And as with the Passionists, so with the other orders: after early enthusiasm for the visions they eventually followed the diocese into opposition. Only a few individuals persisted.

The Franciscans carried the most weight in Gipuzkoa, with houses in Zarautz, Oñati, and Aranzazu. The believers and friars I talked to agreed that the Franciscans came to oppose the visions strongly; believers attributed this to a fear of competition. A man in Tolosa claimed Aranzazu was the place Bishop Múgica met to plot against the visions. Another rumor had it that a Franciscan outspoken in his opposition to the visions had fallen to his death while directing the construction of the church of Our Lady of Lourdes in San Sebastián.[57]

B 301 mentions a Franciscan missionary assigned to India who was cured of gout at the shrine. For the plot see Lucas Elizalde, Tolosa, 6 June 1984, p. 2, and for the rumor see Ducrot, VU, 23 August 1933, p. 1331.

The Franciscans were from the same kinds of families as the seers and believers, so their opposition was especially hard to bear. Indeed, of all the religious I visited, it was among Franciscans at Aranzazu that I found most sympathy—not for the seers, but for the believers. When the seer Martín Ayerbe of Zegama became a religious, he joined this community.In the 1920s about thirty thousand pilgrims went to Aranzazu each year. This was a relatively small number for that period, especially compared to the crowds at Ezkioga. But Aranzazu was the major Marian shrine in the province and one to which many of the believers in Ezkioga were devoted. They recognized the apparition of the Virgin in Aranzazu as a local precedent, and when the Ezkioga site was declared out-of-bounds, some believers went to Aranzazu to meet and pray.[58]

M. Ayerbe died before becoming a friar. A seer from Zaldibia was a novice in 1952. Figures from José A. de Lizarralde, in Guridi, AEF, 1924, pp. 97-100.

In 1919 Capuchin preaching had sparked the visions in Limpias. The Capuchins had six houses in the wider vision region but none close to Ezkioga. Some of the friars involved with Limpias took an initial interest in Ezkioga, but many became convinced that the visions at Ezkioga were a plot to embarrass Catholics.

Pedro Balda, the town secretary of Iraneta, told me that he and Luis Irurzun went to Pamplona in an attempt to leave the notebooks of Luis's messages with Balda's uncle, a Capuchin. Luis went into a vision, with Balda's uncle in prayer alongside him, but as he came out of it the superior arrived and gave him a kick. Balda and Luis decamped with the notebooks and Capuchin alms-gatherers spread the word that Luis had been booted out of the house.[59]

Damaso de Gradafes at Basurto, who had taken his youth group to Limpias, took the members to Ezkioga as well, and Andrés de Palazuelo, who wrote in favor of Limpias, published an article on Ezkioga in El Mensajero Seráfico, 16 September 1931. For Ezkioga as plot Enrique de Ventosa, Salamanca, 5 May 1989, and Francisco de Bilbao, Madrid, 6 May 1989. Pedro Balda, Alkotz, 7 June 1984, p. 16; he and Luis had first tried to leave Luis's notebooks at the Jesuit house in France, La Rochefer, but they failed. A sympathetic Capuchin, P. Bernabé, occasionally preached in the Goiherri. The Claretians had been sympathetic to the Limpias visions and printed favorable articles about Ezkioga in their national magazine, Iris de Paz. But I know of no Basque Claretian involvement.

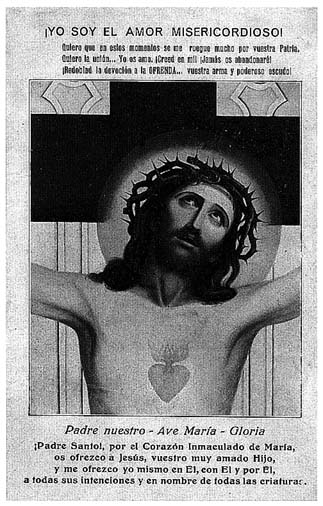

Dominicans went to Ezkioga from Montesclaros in Cantabria and nearby Bergara and reported for El Santísimo Rosario , the magazine that first publicized Fatima in Spain. But not all Dominicans were receptive. Luis Urbano, the man who single-handedly discredited the visions at Limpias and Piedramillera in 1919 and 1920, published in his magazine Rosas y Espinas the first negative article about Ezkioga written by a religious. In this period Dominicans in Salamanca, Madrid, and Pamplona had a kind of rival to Ezkioga: the divine messages relating to Amor Misericordioso, Jesus of Merciful Love, received by Marie-Thérèse Desandais (1877–1943). The abbess of a convent of Dreux-Vouvant in the Vendée, Desandais published her revelations under the pseudonym P. M. Sulamitis. González Arintero, the Dominican who published Maria Maddalena Marcucci, first came across Desandais's writings in 1922. He dedicated much of the last seven years of his life and the pages of his journal to spreading them. In the late 1920s a wealthy laywoman in Madrid, Juana Moreno de Lacasa, financed the publication of the messages in pamphlet form by the hundreds of thousands. In San Sebastián the count of Villafranca de Gaytán de Ayala persuaded a number of bishops to allow leaflets to be inserted in diocesan bulletins. And Dominicans spread the devotion with lectures and a special magazine and by installing paintings of the Merciful Christ in their house in Madrid in 1926 and in Pamplona in 1932. The Ezkioga seer Jesús Elcoro, given to seeing nuns, claimed to see Sulamitis with the Virgin.[60]

For Arintero and Merciful Love see Fariñas, "Apostol"; Suárez, Arintero, 275-309; and Staehlin, Padre Rubio, 247-251. See Gaytán de Ayala obituary in VS 40, no. 361 (January-February 1959), pp. 69-70; he gave a speech about the devotion in the Vitoria seminary in February 1932, Gymnasium, 1932, p. 124; the Sulamitis leaflets received the nihil obstat in Vitoria by March 1929. P. M. Sulamitis, España'ko Katolikoai (To Spanish Catholics), was published in Bergara with the imprimatur of Justo de Echeguren and Manuel Lecuona in 1932. For paintings, see Fariñas Windel, "Apostol," 114, and "Un Cuadro de Ciga," La Tradición Navarra, 29 December 1931, pp. 1-2. The Dominicans of Atocha in Madrid published the magazine Amor Misericordioso. For Jesús Elcoro, R 8.

The messages of Merciful Love posed fewer problems for the church than those of Ezkioga. Very little of their content was bound by time and place. They were the product of a single visionary who could be silenced at any time; they came through a respectable journalf and enjoyed ecclesiastical permission. They were not propositions to the hierarchy from the lay public, much less from poor rural children, housemaids, farmers, and workers. Inspired females could be heard only if cloistered and directed. It helped to disguise their identity. Most readers did not know that J. Pastor (Marcucci) and P. M. Sulamitis (Desandais) were women. The Merciful Love messages too were quite different from those of Ezkioga, emphasizing the mercy of God as good father, not the anger and chastisement of God offended. In 1931, when events seemed to be going against Catholics and Catholicism in Spain, the idea of a chastisement was perhaps more in line with contemporary developments. Merciful Love had less appeal to the Basque public than darker calls for penance, atonement, and sacrifice.

"I am Merciful Love!" holy card, ca. 1932

Two orders with influence in the area, the Benedictines and the Jesuits, kept their distance from the visions. At the Benedictine monastery of Lazkao, eight kilometers from Ezkioga, most monks strongly opposed the visions and told their confessants not to go.[61]

J. B. Ayerbe claimed to García Cascón, 22 March 1934, 3 pages, typewritten (AC 416), that Conchita Mateos convinced her confessor at Lazkao, Padre Leandro. A seer from Zaldibia entered a Benedictine convent in Oñati: Rigné, Ciel ouvert, p. D.

The Jesuits did not report the visions in their magazines even in the first months. The elite male order in Spain, they educated Spain's elite. They were largely an urban order and were less likely to be related to the seers at Ezkioga. I know of few direct Jesuit links even to believers.But even before Laburu got involved, the Jesuits could hardly ignore what was happening. Their great shrine at Loyola was only twenty kilometers away, and the confessionals periodically filled with people from the vision sessions. Pilgrims

to Ezkioga from other parts of the country and abroad made detours to see Loyola and inevitably commented to the fathers about the visions. Nonetheless, in the summer and fall of 1931 the Jesuits were keeping a low profile. In May Jesuit houses had been burned down in Madrid and elsewhere, and they knew most republicans thought the order should be dissolved. Antonio de la Villa accused them in the Cortes of promoting the Ezkioga visions, the accusations itself a cause for prudence.[62]

B 51-52, 751-752. See the Azpeitia correspondent's passionate reply to de la Villa in A, 23 August 1931, p. 2.

Examples of Jesuits speaking even guardedly in favor of Ezkioga were thus rare. A Jesuit at Loyola told two French visitors from Tarbes that the purpose of the visions at Ezkioga and Guadamur was not to set up a shrine like Lourdes but to warn of impending persecution and to revive the faith of Spaniards. Salvador Cardús of Terrassa corresponded with a Jesuit in India who was interested in Ezkioga and Madre Rafols, but even this distant friend requested great discretion lest "someone else, with indiscreet zeal, might later go around saying to people, 'A Jesuit said this,' and many times it turns out that what was said with the best of intentions is not interpreted in the same way."[63]

French visitors at Loyola at end of August, "Les Apparitions d'Ezquioga," La Croix, Paris, 15 October 1931, p. 3, from Le Semeur, Tarbes. Pere Pou i Montfort S.J. to Cardús, Sacred Heart College, Shembaganur, Madura District, 18 August 1932.

Believers resented the Franciscans but held no grudge against the Jesuits, despite Laburu's hand in their defeat. A Jesuit from Betelu was the key person distributing the prophecies of Madre Rafols. And the ex-Jesuit Francisco Vallet had prepared the followers of Magdalena Aulina. Male seers went to the Jesuits for spiritual exercises. Even the Ezkioga souvenir shops of Vidal Castillo had a Jesuit connection: they were owned by the Irazu family, who ran the stands at Loyola and Limpias. So however much the Jesuits tried to keep their distance from Ezkioga, they formed in fact a part of the context that nurtured the visions.

Hence we find visions in which the seers protest the expulsion of the Jesuits, settle into stances that seem to replicate those of Ignacio de Loyola in paintings or in the wax statue at Loyola, and report seeing Loyola himself giving Communion. And, as in the case of the Benedictines, believers occasionally came across a Jesuit they considered sympathetic. Nuns from Bilbao persuaded one Jesuit to go see Gloria Viñals when he was in Pamplona, and López de Lerena alleged that he subsequently had a vision of his own in the cathedral. After the war the Jesuit confessor of a seer from Azkoitia introduced him to another Jesuit in a high position in the Vatican. But the believers I talked to knew of no member of the order who worked actively or spoke out publicly for their cause, and the documents I have read mention no Jesuit other than Laburu who actually went to Ezkioga.[64]

On the expulsion of Jesuits, Cardús cites a vision by a female seer, 1 September 1931, who complained to the Virgin, "What will we do without them?" and Burguera cites one by Benita Aguirre, 30 June 1933 (B 497); at the end of 1932 J. B. Ayerbe claimed the support of Padre Iriarte, "que está considerado en gran santidad" ("Las maravillosas apariciones," AC 2:4). For Viñals (Padre Zabala): Sebastiáan López de Lerena to Ezkioga believer, 2 September 1934, private collection. For Azkoitia (Padre Imaz): Juan Celaya, Albiztur, 6 June 1984, pp. 27-28.

Carmelites took more interest. Since the time of Teresa de Avila and Juan de la Cruz, the Discalced Carmelites considered visions, revelations, and investigation of such phenomena as their particular expertise. And although Basque and Navarrese Carmelites were standoffish on the whole about Ezkioga, some individuals were sympathetic. The order drew on rural and small-town Basques to

supply missions in South America and India. Children participated in this effort through La Obra Máxima , based in San Sebastían.[65]

In addition to the small house of Carmelites at Altzo above Tolosa, there were others in Bizkaia at Larrea, Begoña, and Markina and in San Sebastián, Pamplona, and Vitoria.

Believers placed their hopes for a convincing public rebuttal of Padre Laburu on the Carmelite Rainaldo de San Justo, for two decades a professor in Rome. I talked to his nephews, the well-known Nationalist clergymen Domingo and Alberto de Onaindía. He told them that one little element of truth in an apparition was enough to give it great significance.[66]

Domingo Onaindía Zuloaga, Saint Jean de Luz, 11 September 1983. Padre Rainaldo had written in Vida Sobrenatural about Thérèse de Lisieux, who was canonized in 1925. Pilgrimages went to Lisieux from Pamplona in 1923 and 1926, but by 1931 the first flush of the devotion had passed and Saint Thérèse appeared to the Ezkioga seers infrequently. J. B. Ayerbe recorded her giving blessings cheerfully in visions of Asunción Balboa in Urnieta and Tolosa in 1934 and María Nieves Mayoral in Urnieta in 1935 (AC 209, 210, 213, 372).

In Pamplona Padre Valeriano de Santa Teresa, known for processions of children in honor of the Infant Jesus of Prague, supported confessants who had attended vision sessions. And at Altzo before the Civil War Padre Mamerto, a simple man from Bizkaia, a naturalist, friend of animals, and healer, was a firm believer in the visions and was not afraid to proselytize for them.[67]For Padre Valeriano (b. Amorebieta, 1865), DN, 22 December 1933, p. 5, his golden anniversary; Maritxu Güller, San Sebastián, 4 February 1986, p. 15; and R 52. A street urchin converted by a flower from a seer went for confession to the Pamplona Carmelites (Rolando, DN, 19 October 1932). For Padre Mamerto: Pío Montoya, San Sebastián, 11 September 1983, p. 4, and 9 February 1986; Domingo Onaindía Zuloaga, Saint Jean de Luz, 11 September 1983; and P. Santiago Onaindía, Larrea, 10 February 1986.

The Carmelite who took the task of testing seers most seriously was Doroteo de la Sagrada Familia, born Isidro Barrutia in Eskoriatza, another enthusiast of the cult of the Infant Jesus. From 1933 until 1936 he was the superior of the Carmelite house in San Sebastían. Shortly after Bishop Múgica's edict against the visions, Padre Doroteo attended one of the visions of a seer in Tolosa. He knew Juan Bautista Ayerbe and let him know he was Patxi's spiritual director. When I mentioned Doroteo's involvement to his brethren, they said it was in character. He may have been the Carmelite who made Ramona swear that her messages were true and one of those López de Lerena and others mentioned as having tested the seers.

Many religious, especially Carmelites, submitted the seers to mystical tests, such as having them end their visions by mental command from their spiritual superiors, and they assured us that the phenomenon that occurred in the seers was, without a doubt, of a supernatural character.[68]

Doroteo, Historia prodigiosa; in Tolosa, Ezkioga believer to Cardús, 12 October 1933; on Doroteo and Patxi: Ayerbe to Cardús, 24 October 1933; Padre Santiago Onaindía, Larrea, 18 October 1986—"era muy aficionado a esas cosas"; on Doroteo and Ramona on 4 February 1933: Rigné to Ezkioga believer, Santa Lucía, 27 December 1934, private collection; quote from López de Lerena et al. to bishop of San Sebastián, 1952, p. 5.

Burguera's volumes on God and art were printed by the Carmelites of Valencia, and when he went to Rome in 1934 he carried a letter of introduction to the general of the order.[69]

B 351; for Rome trip, Sedano de la Peña with Lourdes Rodes, Barcelona, 5 August 1969, p. 42.

The Carmelite Luis de Santa Teresita was the brother of a child seer from Ormaiztegi. His parents believed deeply in the visions, and the Catalan supporters often stopped at their house. He was studying for the priesthood when the visions started and was ordained in 1933. He eventually was named a bishop in Colombia and died there in 1965. Two of his sisters became nuns. Brothers of other seers became Jesuits, Dominicans, and Franciscans. Before and after the visions, seers, believers, and the religious professionals around them were often related to one another.[70]

In some of the other orders there were one or two religious who pursued an interest in the visions, like Padre Maguncio of the Clérigos of San Viator in Vitoria, or the Redemptorist Padre Mariscal, known within the order for his interest in the marvelous: Christian, Moving Crucifixes, 46-50; Balda to Mariscal, Irañeta, 11 October 1934, AC 250.

The Brothers of Christian Schools had at least ten schools in Basque-speaking Spain, including those in Zumarraga and Beasain; they brought students to the site in February 1932 (Surcouf, L'Intransigeant, 20 November 1932). The Marist Brothers were expanding and had eight schools in the same zone, including the one Cruz Lete attended. I know of no involvement of the Brothers of the Sacred Heart, who had a novitiate and six schools in Gipuzkoa, or of the Brothers of Christian Instruction, who had six in Bizkaia. These teaching orders were of French origin.

A few sympathetic members of the clergy can have a disproportionate effect on a religious movement stigmatized as unorthodox. In the seers' search for confessors and spiritual directors they were in a buyer's market. There were priests

in their own towns and villages, priests in surrounding towns, priests in rural religious houses, and finally priests in the cities and neighboring dioceses. These clergymen offered a broad spectrum of attitudes toward the visions, and any of them could dispense sacraments and absolution. So it was relatively easy for seers to find sympathetic clergy and religious. At the beginning of 1933, in spite of the Laburu lectures, Juan Bautista Ayerbe knew personally ten priests who were open believers and another twenty who believed in private.[71]

J. B. Ayerbe, "Las maravillosas apariciones," AC 2:4.

Bishops could not control what the laity, clergy, and religious did in private. Múgica could make rules and decrees, but in the protected secrecy of the confessional information and grace could flow in both directions. In selected female houses the Ezkioga female seers found curiosity and goodwill as well as a clientele for spiritual services. Some priests and members of orders found support for their devotional agendas in the visions. But others had practical, personal uses for direct contact with the divine. In the intimate communities of cloistered nuns in particular these two modes of belief coincided, the interests of the order and the interests of a specific set of human friends, living and dead. Some houses became unanimous centers of belief.

There could be many reasons for persons in religion to support the visions, if discreetly. But there were few reasons to oppose them actively and vocally. Such opposition would earn the enmity of fervent believers, who in Gipuzkoa and the Barranca were virtually everywhere. Clergy opposed to the visions were generally more than happy to leave the task of discrediting them to the vicar general, the bishop, and Laburu. The Dominican Luis Urbano and the Carmelite Bruno de Sainte Marie, sharply opposed to the visions, were safely distant in Valencia and Paris. Republican ridicule was insubstantial. In Gipuzkoa only the layman Rafael Picavea took up the thankless task of examining the visions critically. Even Laburu did not publish his lectures in anything like their entirety. Only in Tolosa, Legorreta, Zaldibia, Legazpi, and Ezkioga itself did parish priests rigorously enforce diocesan orders to deny Communion to seers and believers.

It is not difficult to be enthusiastic about alleged religious visions or miracles. As long as the seers seem to act in good faith it is more difficult to work up a strong head of indignation against them. For six months El Día , a newspaper administered by priests, described the visions in detail. But after the diocese spoke against the visions, El Día fell silent. Thereafter it provided almost no new information or analysis of the phenomenon. If the apparitions were not "true," how could they have come about? After Laburu's talks, Bishop Múgica's circulars alone answered the articles and books in favor of the visions. As in other spheres of public life in Spain, enforcement of rules was left to the authorities.