Albertina Sisulu:

A Woman of the Soil

Albertina Nontsikelelo Sisulu is a person of enormous dignity and presence. She has been a sustaining wife to a husband who was in prison for 26 years and a sacrificing mother to five children. She has also emerged as a leader and symbol of struggle in South Africa.

The mother of a nation not yet born, she has lived through the birthpangs and trauma of struggle. 'Mama', as she is affectionately known, is a name that can scarcely be denied her. Imprisoned on many occasions and banned from 1964 to 1983 (which included ten years of house arrest), her 90 days of detention under the Suppression of Communism Act in 1963 stand out most vividly in her memory. She recalls a policeman coming into her cell late one night:

He told me my four-year-old child was in the intensive care unit of Baragwanath Hospital, suffering from pneumonia. "Tell us where your husband is and you are free to go," he told me. Shattered by the news I also realised that for the sake of both my husband and my child I could not betray the struggle. I told the policeman this. His eyes were hard and determined. "Then you will die in this cell and rot in the ground. You will not see your husband nor your children again." I looked at him and found myself saying: "I was born of the soil. I can only become part of it again." I was determined that even if I were to die in that cell I would die without selling out the nation. I prayed that God would give me the strength to do what I knew was right and not to allow that policeman to know my inner fear.

Mama speaks of another occasion when she realised that if she were to die, six members of her family would not be able to bury her. Her husband was serving a life imprisonment on Robben Island, two of her children were in exile, another was in jail, an adopted son was serving a five year sentence on Robben Island and her seventeen-year-old grandson had just been arrested. "Those were dark days," she recalls. "The struggle has demanded a high price from many of us."

The Man in the Bedroom

I ask Mama to speak about what sustained her during those dark days, what kept her going through decades of struggle. "Well, it is difficult to convince some people who ask me that question," she replies. "Hopefully you as a minister will understand. I believed in God, and repeatedly reminded myself that nothing is without an end. I had an inner God-given assurance that one day we would be free. I've always known this to be the will and purpose of God for all people." She offers to give me a concrete example of her trust in God.

My husband was terribly worried, especially during the earlier part of his imprisonment, as to whether I was able to cope financially and otherwise. I told him not to concern himself because there was a man in the house who assisted me. He was

taken aback and asked, "A man?" I explained that I was talking about the Almighty God.

God was like a father to me, and still is. I used to look up into the corner of my bedroom and speak to him as though I could see him. He seemed to answer me and guide me through many a very difficult time.

Since Mama Sisulu refers to God as a man and as a father, I ask how she feels about feminist notions of God as a mother. Is it not important to find more inclusive notions of God? "Well, for me God is a father," she replies. "I find it difficult to conceive of God in any other way - perhaps because of the positive relationship I always had with my father, and later with Walter (Sisulu). The males with whom I have enjoyed the closest relationships in life have never tried to dominate or oppress me. They have given me a dignity that has enabled me to realise my potential as a person—as a woman in my own right. My sons have similarly always shown me respect. She recalls her early relationship with her father:

I was fifteen years old when my father died. He was only forty-eight years old, dying from what I think must have been some kind of miners' disease, because he worked on the mines for many years. Shortly before he died, he called the children to his bedside, explaining that he was going to leave us soon. He appealed to us to look after one another and then turned to me: "Nontsikelelo," he said, "if you were my eldest son it would have been a natural thing for me to ask you to take responsibility for your sisters and brothers, but you are not. You are, however, strong and you are able to do what I am asking you, which is to take responsibility for your brothers and sisters." It could not have been easy for my elder brother who was standing next to me, but I resolved that day that I would honour my father's trust in me.

This was a formative moment in my life. My father, who had loved me and cared for me, now gave me the responsibility of being a person in my own right. He did not require me simply to fit into the traditional male-dominated hierarchy of responsibility.

Mama resolved not to marry, to become a professional person and to care for her brothers and sisters. "It was for me as though my father's wish was a God-given vocation. Well, as you know I did marry. I met Walter when he was already an active member of the African National Congress Youth League. We married in 1944. I was fortunate, in that I encountered a man who treated me as an equal, as a person who could be trusted to meet the challenges of life with him."

Mama argues that perceptions of the divine may emerge out of one's

lived experience. "Males have played positive, creative and supportive roles in my life, so I personally do not have any difficulty in referring to God as a man or as a father." Conceding that some others have not had these positive gender relations, she is ready to allow that the pursuit of an alternative understanding of God or metaphor for the divine is a legitimate exercise. Her reflections become quite philosophical:

Perhaps we all create God in our image or understanding of life. . . The point is, we don't really know who or what God is like, we therefore tend to see God in relation to an experience that is central to our existence. I suppose I have done this with my father, as someone who always believed in me and was ready to come to my assistance. He enabled me to deal with the challenges of life. I at the same time accept that for others God is a mother. It all depends on one's own personal experiences.

Different people have different names for God. The missionaries gave our people names for God, but we knew that God long before they came. We called him Modimo, Unkulunkulu and Modiri. So I accept that the struggle for names continues and this is important. . . It is helpful to remember that in so doing we are influenced by life's experiences. This frees us to allow people to relate to God in terms of their own reality. When we do so we realise that most of us are seeking to give expression to a common reality or dimension of life.

Having said this, Mama again stresses the importance of the personal dimension of her religion. "For me God has always been a father and I suppose he always will be. Maybe I am too old to change. I simply ask people to accept that this understanding of God has got me through some very difficult times in life."

African and Christian

Religion for Mama Sisulu is, however, more than talk about God, it has to do with living a life of responsibility and liberation. She sees this as grounded in both Christian and traditional African beliefs. "My notion of God as a father is grounded in me being affirmed and entrusted as a woman to take responsibility for life. Religion is about taking that responsibility." At this point Mama again resorts to normative church language in order to make her point.

God demonstrated his expectations of the Church by sending his only son, Jesus Christ. Christians are, in turn, called to care for those for whom Jesus died—that is, for all people. This means that the Church should be in the forefront of the struggle for the

liberation of the oppressed people. They are the special responsibility of the Church.

This essential belief makes her critical of the Church. "The Church has not fulfilled this responsibility," she continues. "People are dying, while too many Christians are content to remain inside their churches, read their bibles and say their prayers. One cannot claim to be a Christian without leaving the security of the Church and participating in the struggles of the oppressed. If Jesus could go to the cross to defy the unjust laws of his time, so must the Church. This is what God expects of us. It is part of our responsibility."

Mama Sisulu's understanding of the task of the Church in South Africa is rooted in biblical teaching. It reflects a traditional African understanding of life. She sees her religious experience as Christian, while giving expression to a belief in African notions of belonging, of extended family and community. It is the latter which she believes needs greater emphasis in contemporary society, to ensure that the greed and aggression that are so prevalent among people, but quite foreign to traditional African culture, are overcome. Although western ideas have contributed a great deal to contemporary African culture, her concern is that the loss of many traditional values has undermined our common struggle. She sees African togetherness, the sense of being an individual in relation to others and the need to care for one another, as something we need to carry from our past with us into the future. In traditional African society, religion plays an important role in this regard. Her observations are succinct:

For the traditional African, the divine is at the centre of the community. God binds the community together in common struggle. Religion teaches us to care for one another, to bear one another's burdens and to rejoice in one another's successes.

Mama Sisulu laments the loss of what she calls the 'African way'. It is this loss, fuelled by the aggression of people in their fight against apartheid, that she sees as having contributed to the breakdown in communication between the youth and their parents in African society.

In former generations one would never respond to a person of one's parents' age in the kind of way in which many young people do today. Old people were treated with respect. That is how I grew up and that is the kind of behaviour I would like to see among our children today. We need to rediscover a sense of family belonging and mutual support for one another. When I say this I know some think that I am just an old woman; one who is unable to accept

change. My response is to ask whether the collapse of such traditional values has made for a better world or not. I think the answer is clear.

Arguing that the recovery of this traditional value system is an important dimension of the solution to South Africa's problems, she continues, "It is only when people begin to show consideration and respect for one another that South Africa will be able to enter a new age of peace and democracy. I am suggesting that in African traditional culture we have the outlines of a system of social behaviour that can assist us in the reconstruction of society".

A Social Vision

Continuing to speak of traditional African life, Mama Sisulu relates this observation to the contemporary discussion on economics:

Our great-grandparents used to be seasonal wanderers. In the winter they would move to warmer areas and in the summer to cooler regions. The men would hunt for animals and the women would take responsibility for agriculture and cooking. The work was done communally and what was produced was shared among the entire community. Today this sense of community has been lost. It is probably gone forever.

We must in some way preserve the sense of working together and create a system of economic life that ensures that we all share in the profits. This sense of sharing cannot, however, be imposed on people. It can only emerge from our living as a family, from within a compassionate community that has a sense of belonging. Our first task in this regard is the creation of a sense of being one people, a united country and an integrated nation. In the absence of this unity, I have some concern about those who speak as if we can force people to share. The South African Communist Party (SACP), for example, speaks of a common destiny and economic socialism. This is fine. My question is how to create a common sense of belonging that makes this possible. Maybe we never will. Maybe society is simply too complex today for the communal ideas that are part of our African tradition to be reproduced.

Aware of the hard work and perseverance that are necessary to ensure that there is progress at the social and economic level, Mama is sceptical about some of the suggested solutions to prevailing problems. "My concern," she observes, "is that socialism does not always encourage responsible living. It sometimes discourages self-initiative and hard work. Somehow we have got to create a system that encourages hard work, personal initiative and responsibility. This is the appeal of capitalism, it provides an incentive. However, I feel

strongly that people must learn to care for one another—for the weak and less able. This is the appeal of socialism." Insisting that her understanding of economics is insufficient to suggest how to create an economy that promotes both an incentive to work and a willingness to share, she sees no reason why we should not demand that both capitalists and socialists give their attention to this in a way they have not done before.

The SACP was the first to fight against social and economic injustice in this country and therefore I instinctively support the Party. The communists have not, however, convinced me that it is possible to translate their economic vision into reality, but neither have the capitalists convinced me that their system will take care of the poor. Perhaps it is only as we continue to share our ideas, and workers and business people take seriously the challenge facing the country, that a new economic system will emerge—a system that addresses the need for a dynamic and growing economy as well as ensuring a fair distribution of wealth. It will certainly need to be different to the form of socialism that we have seen in Eastern Europe and different to the capitalism of the West, which leaves a few people rich and the masses impoverished.

Remembering the Past

Responsibility, perseverance and dedication are important elements in Mama's vision for a new society. They reflect her own journey through life, which functions for her as a model of what others can do and how the nation can be rebuilt.

The second eldest of five children, she was born in the Transkei in the district of Tsomo. By the time she was 15 her parents were both dead. She had to leave school to care for her six-month-old sister because her grandparents, with whom they lived, were too old and frail to do so. From this early age Mama Sisulu had a sense of commitment to her brothers and sisters, stemming back to her father's dying request that she care for them. She was at the same time determined to complete her schooling.

After my parents died I missed two years of school. When I started school again I soon made good progress and was given the opportunity, together with other students in the district, to write an aptitude test designed to identify the three top students who would qualify for a bursary to attend high school. I won second place, but when they discovered my age they disqualified me. I was distraught, thinking that I had lost my chance of gaining an education. A local priest intervened and spoke to my grand-

parents who decided to use their meagre resources to pay for my education. I knew what it cost them and I was determined to work hard.

She initially wanted to become a teacher, but circumstances did not allow this. She thought seriously about becoming a nun, but realised that this would require her to dedicate herself to the Church which would not enable her to care for her brothers and sisters, so she went to Johannesburg where she trained to become a nurse. "Soon I was able to send money home to assist with the care of my sisters and brothers and to repay the school fees which my grandparents had paid. I felt I was beginning to fulfil the commitment which I had made to my father and to meet my responsibility to my brothers and sisters. This did me as much good as I hope it did them! I was learning that it is possible to meet one's obligations in life and that hard work and dedication can enable one to rise above many challenges."

It was at the Johannesburg General Hospital that the young Albertina faced the harshness of apartheid for the first time. "At home I had known poverty but never the full impact of racial discrimination. Employed in what was then known as the Johannesburg Non-European Hospital, I experienced the reality of white baasskap (domination). Even after I had worked my way up to be the senior nurse, in the absence of the sister-in-charge a junior white nurse would be called in to take charge of the ward in which I worked. I faced what black people have lived with daily in South Africa, which is the knowledge that colour is more important than skills! It is prejudice that has persuaded some of our young people that there is no point in acquiring skills at school or anywhere else. This is but one instance of the way in which apartheid has undermined the culture of learning. I also saw the aggression of whites against blacks and the contrast between white wealth and black poverty." During this time she was introduced to the ANC by Walter Sisulu, her future husband. She joined the movement almost immediately. Married in 1944, her initial hopes of a quiet married life were soon shattered. "I had hoped for a normal family life, providing for my husband and children the stability of a home that I never had, but that was not to be."

The participation of the Sisulus in the struggle against apartheid made them the victims of sustained state intimidation and persecution. Mama Sisulu was first arrested in 1958 for participating in an anti-pass protest, and imprisoned for four weeks. In 1963 she was again arrested and held in solitary confinement, under the Suppression of Communism Act, for three months. On her release she was

banned first for five years, and then on several occasions after that. Walter Sisulu who had, in turn, been imprisoned and detained on several occasions, was during this time convicted of furthering the aims of a banned organisation and organising a national stay away. Released on bail, pending an appeal, he was under 24-hour house arrest. On 20 April 1963 he went underground to join Umkhonto we Sizwe. Three months later he was arrested in a police raid on the secret headquarters of the ANC at Lilliesleaf Farm. Found guilty of high treason he was imprisoned for life on Robben Island. With this, a new chapter of pain and hardship began for the Sisulus, removing any possibility for a normal family life.

I was left alone to care for our children and battled financially. I wanted to give my children a good education, and feared that I would not have the money to do so. When they were able to go to school I was unable to visit their teachers as my banning order prevented me from entering any educational institution. I was very concerned about my children. These were bad times, but the community did a lot to help me. The importance of community, of belonging and of caring for one another, was again made real to me.

The pain of those years seems to resurface as Mama Sisulu recounts the events. Deeply attached to her husband, she recalls the pain of being separated from him.

"The worst part of my banning was that I could not visit Walter very easily on Robben Island. I had to apply for special permission and sometimes this was only granted the day before the expected visit or even the day after. This sometimes meant the cancellation of a visit for which I had waited for months. I never got used to having to deal with that kind of uncertainty. On several occasions I was obliged to forfeit my visits as I did not have enough money to fly to Cape Town and the train took too long." The few days she was allowed to be out of Johannesburg was simply insufficient to travel by train.

"Even when I did manage to get to Robben Island, the visits were very strained experiences, especially in the early days. They caused a number of happy and yet depressing emotions within me. At first only one visit of thirty minutes was granted a year. And, on some occasions it was cut short because we mentioned the name of someone whose name did not appear on the prison authorities' list of family members. The rule was that we were only allowed to talk about family affairs and family members. One one occasion the visit was terminated after 15 minutes."

In 1983 Mama herself was again arrested. Charged with furthering the aims of the ANC at a funeral by singing ANC songs, handing out pamphlets and draping an ANC flag over the coffin, she was sentenced to four years imprisonment. Her conviction was, however, set aside on appeal. In 1985 she, together with 15 others, was charged with high treason, but the charges against her and 11 of the other accused were withdrawn. In 1988 she was again served a restriction order, preventing her from travelling outside of the Johannesburg area. "I never really got accustomed to the many restrictions and arrests that I suffered," she observes in response to the obvious question. "I never quite got used to it. Each time my nerves played-up all over again. The anxiety and the concern resurfaced. But I knew that this could not go on forever. I never doubted that we would win. God gave me this assurance."

Women

I ask Mama to speak specifically about the place of women in the struggle. "There is certainly sexism in all structures of society, including the struggle for democracy and the ANC," she observes. "It is a woman's right and obligation to fight against this discrimination. There are, however, different ways of doing this. I have already spoken about the positive relationships which I experienced with my father and my husband. I have also spoken of other women who have not enjoyed this kind of positive encounter with men. Our different experiences probably affect the way in which we respond to institutional and other forms of sexism. I am concerned about the kind of feminism which is rooted in the aggression of a past experience, which is then directed against all men. I am also concerned about the kind of narrow individualism that is sometimes isolated from other aspects of our struggle—in trade unions, among the youth and the unemployed. Women's concerns must be located within and in relation to the entire struggle. It is an inherent part of the total struggle. I do not accept the promotion of a kind of feminism that ignores the need to change the essential structures of society." Concerned to promote the cause of women within this broader context, she speaks of her place in women's organisations.

In 1944 1 joined the ANC Women's League, which was formed to ensure that women's issues could be discussed and acted on. It recognised the fact that men did not understand the problems that affected women directly such as children, maternity grants, education, cost of living and so on. Because some women were

afraid to associate with the ANC but wanted to promote these kinds of concerns, I joined with other women to form the Federation of South African Women (FEDSAW). One of our first major campaigns was the anti-pass protest, resulting in the massive women's march on the Union Buildings in Pretoria. The men were elated because of the number of women we were able to mobilise, but less happy when we promoted specific issues concerning the rights of women in relation to men.

Expressing an understanding for the position of some (notably men), that the issue of women's rights should not be allowed to detract from the broader struggle, Mama is at the same time adamant that specific women's rights be given the fullest attention within the context of the other issues being addressed in the struggle for democracy. "We must strive for a truly non-racist, non-sexist and democratic South Africa. This has major implications for existing relations between women and men just as it does for relations between races. It is very difficult for some men to understand this." But she is optimistic about future rights for women, precisely because of the important role women have played in the struggle over the years.

Women have suffered as much, and probably more, than men over the years. A women is often a mother, and it is a painful thing, perhaps the most painful thing in the world, for a mother to see her child suffer—to see her child being killed. Throughout our struggle men, women and children have died alongside each other. Yet, in more recent years our children have paid a price far in excess of anything that any mother can reasonably accept. No black mother who witnessed the madness of people shooting children in the 1976 Soweto school uprisings and elsewhere has been unaffected by this. It radicalised black women in a manner that perhaps no other event has ever done. It drew women into the struggle at every level—in order to demand an end to the slaughter of our children. As mothers, we were compelled to demand: "Kill us if you must, but in God's name leave our children alone."

It is now our obligation to participate in the next phase of struggle, which is the fight for the rights of our children and the rights of women, together with the rights of all human beings in the new South Africa. We cannot leave this to men. There are certain things we can actually do better than they can.

Quietly, and with great confidence she concludes: "There is a general awareness of sexism beginning to emerge, at least in some sectors of society, in South Africa. This is making an increasing number of women stand up and demand their rights. There is also a small but significant number of men who understand this and support it. We

have along way to go yet, but women's rights are on the agenda and we must keep them there."

Children

Mama Sisulu's concern is for the future welfare of children. She knows that the effects of apartheid will be experienced at every level of existence for generations to come. "No child," she argues, "should ever again be asked to pay the price that our children paid. In the process of helping destroy apartheid, they have in many instances destroyed their own chance to share in the future society in a meaningful manner. People often talk about these children as a lost generation. Maybe they are. I would like to think not. We have got to help restore them to their rightful place in life." Concerned about the loss of vision and hope that has come to characterise the attitudes of many children, her question is a pertinent one: "How can we build a next generation that has hope and a sense of responsibility, if we do not redeem these children?" Asked where we begin, her response is immediate: "By ensuring that the children return to school. There is perhaps no single greater task facing the nation than education," she insists. "Education is often a long way and difficult journey, especially for those who are not well equipped to undertake the journey. It is, however, the only means of self-improvement."

"Some people seem to imagine that after the first democratic government is installed, the inequality and suffering of apartheid will be over. Such thoughts are not only wrong, they are extremely dangerous. We need to teach people that they are the ones who will build the future, that they need to be equipped to do so and that this requires education, training, fortitude and hard work." Mama Sisulu believes there is no easy walk or short-cut to success. While apartheid has denied black children a space within which to succeed, it is the obligation of the entire community to ensure that a new culture emerges within which children will recognise their obligation to succeed for the sake of the entire nation. "Either they must grab this opportunity with both hands or else the noble-minded dreams of our struggle could be reduced to nothing. New values have got to be injected into every aspect of society. It is the obligation of families, Churches and religious organisations, community organisations and government to promote the desire to know, to teach and to learn."

Albertina Sisulu's journey from the soil of her village in the Transkei has been a long and difficult one. She speaks with the dignity and

assurance of one who has gained wisdom and insight from the suffering and hardship endured. Like everyone else whose story is included in this volume, she is grounded in her own context and experience. "We are each required to walk our own road—and then stop, assess what we have learned and share it with others. It is only in this way that the next generation can learn from those who have walked before them, so that they can take the journey forward after we can no longer continue. We can do no more that tell our story. They must make of it what they will." These are the words of one who is, indeed, the mother of a nation that is waiting to be born.

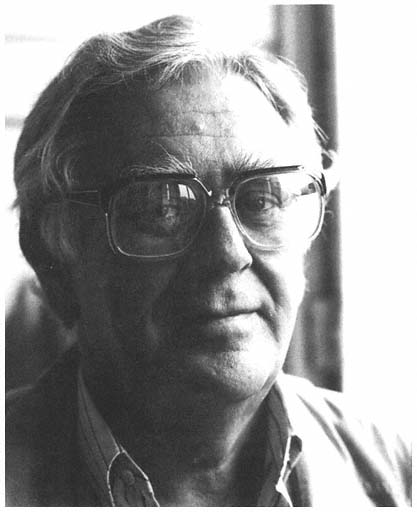

PHOTO ACKNOWLEDGEMENT: Mayibuye Centre, UWC