PART FOUR—

DOCUMENTARY

Since Film Quarterly 's earliest days, documentary has been one of the journal's principal interests. Besides reviews of nonfiction films in every phase of the journal's history, there have been numerous interviews and, of course, a large number of articles on the topic. Highlights have included a thirty-three-page special feature on Humphrey Jennings in the Winter 1961–62 issue; editor Helen Van Dongen's article on Robert Flaherty in Summer 1965; and Alan Rosenthal's interviews with the director, cameraman, and editor of the cinema verité film A Married Couple in Summer 1970.

Bill Nichols and ethnographic filmmaker David MacDougall have long been among the most thoughtful and influential writers on nonfiction film; MacDougall's "Prospects of the Ethnographic Film" appeared in the Winter 1969–70 issue. Of somewhat more recent vintage, Michael Renov's writings are also included in the list of work that must be read by those interested in nonfiction film, past and present. Linda Williams' extraordinary article on history and memory in a number of contemporary nonfiction films places her on that list as well.

A crucial feature of all four articles in this section is that despite, or through, their diverse topic areas, all are theoretical in orientation. They might easily have been included in the Theory section, as a distinctive subsection. Their placement here underscores the fact that documentary is not a genre but, like experimental film, a realm of cinema parallel to but not a subset of fictional narrative.

In "The Voice of Documentary," Bill Nichols argues that there are at least four major historical styles of documentary, each with distinctive formal and ideological qualities. These include the direct address of the Grierson era, which he calls "the first thoroughly worked-out mode of documentary"; a second mode—cinema verité—which sought to capture, through an allegedly transparent style, "untampered events in the everyday lives of particular people"; a third style that

incorporates direct address (characters or narrator speaking directly to the viewer); and a more recent fourth phase, which seems to have begun

with films moving toward more complex forms where epistemological and aesthetic assumptions become more visible. These new self-reflexive documentaries mix observational passages with interviews, the voice-over of the film-maker with intertitles, making patently clear [that] . . . documentaries always were forms of re-presentation, never clear windows onto "reality"; the film-maker was always a participant-witness and an active fabricator of meaning, a producer of cinematic discourse rather than a neutral or all-knowing reporter of the way things truly are.

Throughout much of the article, Nichols makes trenchant criticisms of the defects of the first three documentary styles. These pages are especially valuable because they treat a substantial number of specific films, including several not widely known. As for the fourth category, he makes clear that the "voice" he has in mind is "something narrower than style." It is that which conveys to us "a sense of a text's social point of view, of how it is speaking to us and organizing the materials it is presenting." It is also not restricted to any one feature such as dialogue or spoken commentary. Nichols considers the best instances of this category to be the documentaries of Emile de Antonio and some of the ethnographic films of David and Judith MacDougall.

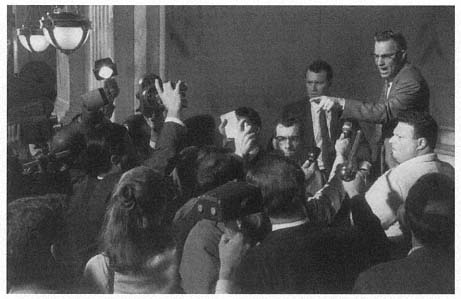

Michael Renov's 1987 article, "Newsreel: Old and New," is a retrospective view of the first twenty years of Newsreel, "a radical film-making collective conceived during the last flush of New Left activism." Newsreel once had offices in seven major U.S. cities but at this point survives "in two versions." California Newsreel, San Francisco, makes and distributes films about the workplace and about South Africa and apartheid, with a new focus on teaching its viewers about the media. Third World Newsreel, based in New York, supports the cultural interventions of the disenfranchised.

In constructing his account, Renov consulted interviews with Newsreel members that appeared in Film Quarterly in Winter 1968–69 and himself conducted interviews with a number of other early Newsreel members. The New Left looked not to American radicalism of the thirties but to the utopian socialism of the very early Soviet Union and specifically to filmmaker Dziga Vertov. But unlike Vertov, with his passionate enthusiasm for the machine, the New Left media activists were mainly negative about technology. Newsreel's most successful early films, both made in 1968, were Columbia Revolt and Black Panther —also known as Off the Pig . Renov is excellent on the conflicts that shaped Newsreel

in the early seventies. Decisions about what films would be made often depended upon who could raise money. Those who could call on family resources or were experienced fund-raisers pretty much called the shots until, between 1971 and 1973, a split developed between the haves and the have-nots. At the same time there was a split between Newsreel's growing Third World Caucus and its other operations, and a division occasioned by a radical feminist faction: most of the men left the collective over the next several months. These gender, color, and class rifts left New York Newsreel a three-person collective in 1973. But From Spikes to Spindles , a 1976 film about Chinese Americans in New York, established Third World Newsreel's reputation for "compact, historically situated overviews of ethnic minorities in crisis." Renov's briefer accounts of California Newsreel and of Third World Newsreel in later years are also of great interest.

"When Less Is Less: The Long Take in Documentary" is the title of David MacDougall's very thoughtful article. He pursues two sets of issues, one having to do with the pressures on documentary and ethnographic filmmakers to cut from their rushes anything that does not move the exposition forward. This is based on the terror of television producers of any "dead spots" in any program they sponsor. This fear is based on the supposed desire of viewers to move on to the next shot/point once they have grasped the preceding one and their boredom if this demand is not met. The other set of issues has to do with the values, contexts, perceptions, and uses of the long take considered in a more general cultural context. In his actual exposition, the author often mixes the two topics.

MacDougall understands the problem of rushes as one of "the ideal and the actual, the object within grasp yet somehow lost." He draws a broad analogy between the way in which individual shots are reduced in length and the way in which the entire body of footage shot for a film is reduced to produce a finished film. He also wishes to question some of the assumptions that underlie these practices. He notes that long takes are better defined by their structural qualities than by their length, and yet, he concludes, "absolute duration does finally matter." Even filmmakers "have seemed unwilling to confront perhaps the most deeply seated assumption of all: that films are necessarily superior to the rushes shot for them." A documentary filmmaker told an interviewer that "the real film was in the rushes." People would drop by his editing rooms at the BBC and become interested in all fifty hours, coming back at various times as though they were watching a serial. In a section called "Qualities Sacrificed to the Film," MacDougall lists the loss of excess meaning, the loss of interpretive space, the loss of the sense of encounter, and the loss of internal contextualization. The author concludes: "Throughout the editing process there is a constant tension between maintaining the forward impetus of the film and

providing enough contextual information so that the central narrative or argument continues to make sense."

Linda Williams begins her argument with a remark by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., that a photograph is "a mirror with a memory," that is, an illustration of the visual truth of objects, persons, and events. Such certainty is not possible in the era of electronic and computer-generated images, in which every photo and film is understood as a manipulated construction. Williams quotes Fredric Jameson on "the cultural logic of postmodernism" based on "a whole new culture of the . . . simulacrum." Jameson argues that it no longer seems possible to represent the "real" interests of a people or class against the ultimate ground of social and economic determinations. Citing both the Rodney King tape and the greatly increased popularity of documentary, Williams points out that the lack of faith in images goes hand in hand with a new thirst "to be moved to a new appreciation of previously unknown truth." This is a rich contradiction that she begins to explore with a number of examples that ultimately end up on one side or the other of the way out of the postmodern dilemma: JFK, Roger and Me, Our Hitler, Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie, Truth or Dare, Paris Is Burning, Who Killed Vincent Chin? , and others.

Errol Morris's The Thin Blue Line is "a prime example of this postmodern documentary approach to the trauma of an inaccessible past." Because of its spectacular success in intervening in the truths known about this past, the film was instrumental in freeing Randall Adams from prison. The film eschews cinema verité completely, exhibiting instead an expressionist style in staging its reenactments of the versions of the murder by suspects Adams and Harris, and by several witnesses. The strategy of Morris's film is to set competing narratives alongside each other by reenacting all of them. Williams turns here to the other film she discusses in detail: Claude Lanzmann's Shoah . Acknowledging that the subjects of the two films are incommensurable, Williams sees a parallelism in method. What motivates both is not the opposition between absolute truth and absolute fiction, but the awareness of the final inaccessibility of a moment of crime, violence, trauma that is irretrievably located in the past. The two filmmakers do not so much represent this past as they reactivate it in images of the present. This is their distinctive postmodern feature as documentarians. In revealing the fabrications and scapegoating when fictional explanations were substituted for more difficult ones, they do not simply play off truth against lie; they show how lies function as partial truths to both the agents and witnesses of history's trauma. One of the most discussed moments of Shoah is the visit of Simon Srebnik to the town where he worked in the nearby death camp. The Poles on the church steps in Chelmno seem happy to see him, but in response

to questions by Lanzmann, at least four of the people collaborate in providing an anti-Semitic account of the Holocaust. This fantasy, meant to assuage the Poles' guilt for their complicity in the extermination of the Jews, actually repeats their crime of the past in the present. Williams concludes that the truth of the Holocaust does not exist in any totalizing narrative, but only, as Lanzmann shows, as a collection of fragments.

The Voice of Documentary

Bill Nichols

Vol. 36, no. 3 (Spring 1983): 17–30.

It is worth insisting that the strategies and styles deployed in documentary, like those of narrative film, change; they have a history. And they have changed for much the same reasons: the dominant modes of expository discourse change; the arena of ideological contestation shifts. The comfortably accepted realism of one generation seems like artifice to the next. New strategies must constantly be fabricated to re-present "things as they are" and still others to contest this very representation.

In the history of documentary we can identify at least four major styles, each with distinctive formal and ideological qualities.[1] In this article I propose to examine the limitations and strengths of these strategies, with particular attention to one that is both the newest and in some ways the oldest of them all.[2]

The direct-address style of the Griersonian tradition (or, in its most excessive form, the March of Time's "voice of God") was the first thoroughly worked-out mode of documentary. As befitted a school whose purposes were overwhelmingly didactic, it employed a supposedly authoritative yet often presumptuous off-screen narration. In many cases this narration effectively dominated the visuals, though it could be, in films like Night Mail or Listen to Britain , poetic and evocative. After World War II, the Griersonian mode fell into disfavor (for reasons I will come back to later) and it has little contemporary currency—except for television news, game and talk shows, ads, and documentary specials.

Its successor, cinéma vérité , promised an increase in the "reality effect" with its directness, immediacy, and impression of capturing untampered events in the everyday lives of particular people. Films like Chronicle of a Summer, Le Joli Mai, Lonely Boy, Back-Breaking Leaf, Primary , and The Chair built on the new technical possibilities offered by portable cameras and sound recorders which could produce synchronous dialogue under location conditions. In pure cinéma vérité films, the style seeks to become "transparent" in the same mode as the classical Hollywood style—capturing people in action,

and letting the viewer come to conclusions about them unaided by any implicit or explicit commentary.

Sometimes mesmerizing, frequently perplexing, such films seldom offered the sense of history, context, or perspective that viewers seek. And so in the past decade we have seen a third style which incorporates direct address (characters or narrator speaking directly to the viewer), usually in the form of the interview. In a host of political and feminist films, witness-participants step before the camera to tell their story. Sometimes profoundly revealing, sometimes fragmented and incomplete, such films have provided the central model for contemporary documentary. But as a strategy and a form, the interview-oriented film has problems of its own.

More recently, a fourth phase seems to have begun, with films moving toward more complex forms where epistemological and aesthetic assumptions become more visible. These new self-reflexive documentaries mix observational passages with interviews, the voice-over of the film-maker with inter-titles, making patently clear what has been implicit all along: documentaries always were forms of re-presentation, never clear windows onto "reality"; the film-maker was always a participant-witness and an active fabricator of meaning, a producer of cinematic discourse rather than a neutral or all-knowing reporter of the way things truly are.

Ironically, film theory has been of little help in this recent evolution, despite the enormous contribution of recent theory to questions of the production of meaning in narrative forms. In documentary the most advanced, modernist work draws its inspiration less from post-structuralist models of discourse than from the working procedures of documentation and validation practiced by ethnographic film-makers. And as far as the influence of film history goes, the figure of Dziga Vertov now looms much larger than those of either Flaherty or Grierson.

I do not intend to argue that self-reflexive documentary represents a pinnacle or solution in any ultimate sense. It is, however, in the process of evolving alternatives that seem, in our present historical context, less obviously problematic than the strategies of commentary, vérité , or the interview. These new forms may, like their predecessors, come to seem more "natural" or even "realistic" for a time. But the success of every form breeds its own overthrow: it limits, omits, disavows, represses (as well as represents). In time, new necessities bring new formal inventions.

As suggested above, in the evolution of documentary the contestation among forms has centered on the question of "voice." By "voice" I mean something narrower than style: that which conveys to us a sense of a text's social point of view, of how it is speaking to us and how it is organizing the materials it is presenting

to us. In this sense "voice" is not restricted to any one code or feature such as dialogue or spoken commentary. Voice is perhaps akin to that intangible, moiré-like pattern formed by the unique interaction of all a film's codes, and it applies to all modes of documentary.

Far too many contemporary film-makers appear to have lost their voice. Politically, they forfeit their own voice for that of others (usually characters recruited to the film and interviewed). Formally, they disavow the complexities of voice, and discourse, for the apparent simplicities of faithful observation or respectful representation, the treacherous simplicities of an unquestioned empiricism (the world and its truths exist; they need only be dusted off and reported). Many documentarists would appear to believe what fiction film-makers only feign to believe, or openly question: that film-making creates an objective representation of the way things really are. Such documentaries use the magical template of verisimilitude without the story-teller's open resort to artifice. Very few seem prepared to admit through the very tissue and texture of their work that all film-making is a form of discourse fabricating its effects, impressions, and point of view.

Yet it especially behooves the documentary film-maker to acknowledge what she/he is actually doing. Not in order to be accepted as modernist for the sake of being modernist, but to fashion documentaries that may more closely correspond to a contemporary understanding of our position within the world so that effective political/formal strategies for describing and challenging that position can emerge. Strategies and techniques for doing so already exist. In documentary they seem to derive most directly from Man with a Movie Camera and Chronique d'un été and are vividly exemplified in David and Judith MacDougall's Turkana trilogy (Lorang's Way, Wedding Camels, A Wife Among Wives ). But before discussing this tendency further, we should first examine the strengths and limitations of cinéma vérité and the interview-based film. They are well represented by two recent and highly successful films: Soldier Girls and Rosie the Riveter .

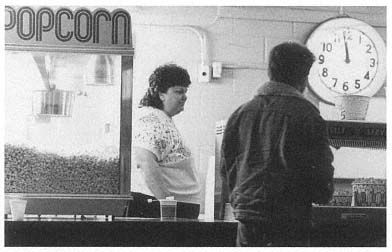

Soldier Girls presents a contemporary situation: basic army training as experienced by women volunteers. Purely indirect or observational, Soldier Girls provides no spoken commentary, no interviews or titles, and like Fred Wiseman's films, it arouses considerable controversy about its point of view. One viewer at Filmex interjected, "How on earth did they get the Army to let them make such an incredibly anti-Army film?" What struck that viewer as powerful criticism, though, may strike another as an honest portrayal of the tough-minded discipline necessary to learn to defend oneself, to survive in harsh environments, to kill. As in Wiseman's films, organizational strategies establish a preferred reading—in this case, one that favors the personal over

Soldier Girls

the political, that seeks out and celebrates the irruptions of individual feeling and conscience in the face of institutional constraint, that re-writes historical process as the expression of an indomitable human essence whatever the circumstance. But these strategies, complex and subtle like those of realist fiction, tend to ascribe to the historical material itself meanings that in fact are an effect of the film's style or voice, just as fiction's strategies invite us to believe that "life" is like the imaginary world inhabited by its characters.

A pre-credit sequence of training exercises which follows three women volunteers ends with a freeze-frame and iris-in to isolate the face of each woman. Similar to classic Hollywood-style vignettes used to identify key actors, this sequence inaugurates a set of strategies that links Soldier Girls with a large part of American cinéma vérité (Primary, Salesman, An American Family , the Middletown series). It is characterized by a romantic individualism and a dramatic, fiction-like structure, but employing "found" stories rather than the wholly invented ones of Hollywood. Scenes in which Private Hall oversees punishment for Private Alvarez and in which the women recruits are awak-

ened and prepare their beds for Drill Sergeant Abing's inspection prompt an impression of looking in on a world unmarked by our, or the camera's, act of gazing. And those rare moments in which the camera or person behind it is acknowledged certify more forcefully that other moments of "pure observation" capture the social presentation of self we too would have witnessed had we actually been there to see for ourselves. When Soldier Girls ' narrative-like tale culminates in a shattering moment of character revelation, it seems to be a happy coincidence of dramatic structure and historical events unfolding. In as extraordinary an epiphany as any in all of vérité , tough-minded Drill Sergeant Abing breaks down and confesses to Private Hall how much of his own humanity and soul has been destroyed by his experience in Vietnam. By such means, the film transcends the social and political categories which it shows but refuses to name. Instead of the personal becoming political, the political becomes personal.

We never hear the voice of the film-maker or a narrator trying to persuade us of this romantic humanism. Instead, the film's structure relies heavily on classical narrative procedures, among them: (1) a chronology of apparent causality which reveals how each of the three women recruits resolves the conflict between a sense of her own individuality and army discipline; (2) shots organized into dramatically revelatory scenes that only acknowledge the camera as participant-observer near the film's end, when one of the recruits embraces the film-makers as she leaves the training base, discharged for her "failure" to fit in; and (3) excellent performances from characters who "play themselves" without any inhibiting self-consciousness. (The phenomenon of filming individuals who play themselves in a manner strongly reminiscent of the performances of professional actors in fiction could be the subject of an extended study in its own right.) These procedures allow purely observational documentaries to asymptotically narrow the gap between a fabricated realism and the apparent capture of reality itself which so fascinated André Bazin.

This gap may also be looked at as a gap between evidence and argument.[3] One of the peculiar fascinations of film is precisely that it so easily conflates the two. Documentary displays a tension arising from the attempt to make statements about life which are quite general, while necessarily using sounds and images that bear the inescapable trace of their particular historical origins. These sounds and images come to function as signs; they bear meaning, though the meaning is not really inherent in them but rather conferred upon them by their function within the text as a whole. We may think we hear history or reality speaking to us through a film, but what we actually hear is the voice of the text, even when that voice tries to efface itself.

This is not only a matter of semiotics but of historical process. Those who confer meaning (individuals, social classes, the media, and other institutions)

exist within history itself rather than at the periphery, looking in like gods. Hence, paradoxically, self-referentiality is an inevitable communicational category. A class cannot be a member of itself, the law of logical typing tells us, and yet in human communication this law is necessarily violated. Those who confer meaning are themselves members of the class of conferred meanings (history). For a film to fail to acknowledge this and pretend to omniscience—whether by voice-of-God commentary or by claims of "objective knowledge"—is to deny its own complicity with a production of knowledge that rests on no firmer bedrock than the very act of production. (What then becomes vital are the assumptions, values, and purposes motivating this production, the underpinnings which some modernist strategies attempt to make more clear.)[4]

Observational documentary appears to leave the driving to us. No one tells us about the sights we pass or what they mean. Even those obvious marks of documentary textuality—muddy sound, blurred or racked focus, the grainy, poorly lit figures of social actors caught on the run—function paradoxically. Their presence testifies to an apparently more basic absence: such films sacrifice conventional, polished artistic expression in order to bring back, as best they can, the actual texture of history in the making. If the camera gyrates wildly or ceases functioning, this is not an expression of personal style. It is a signifier of personal danger, as in Harlan County USA , or even death, as in the street scene from The Battle of Chile when the cameraman records the moment of his own death.

This shift from artistic expressiveness to historical revelation contributes mightily to the phenomenological effect of the observational film. Soldier Girls, They Call Us Misfits , its sequel, A Respectable Life , and Fred Wiseman's most recent film, Models , propose revelations about the real not as a result of direct argument, but on the basis of inferences we draw from historical evidence itself. For example, Stefan Jarl's remarkable film, They Call Us Misfits , contains a purely observational scene of its two 17-year-old misfits—who have left home for a life of booze, drugs, and a good time in Stockholm—getting up in the morning. Kenta washes his long hair, dries it, and then meticulously combs every hair into place. Stoffe doesn't bother with his hair at all. Instead, he boils water and then makes tea by pouring it over a tea bag that is still inside its paper wrapper! We rejoin the boys in A Respectable Life , shot ten years later, and learn that Stoffe has nearly died on three occasions from heroin overdoses whereas Kenta has sworn off hard drugs and begun a career of sorts as a singer. At this point we may retroactively grant a denser tissue of meaning to those little morning rituals recorded a decade earlier. If so, we take them as evidence of historical determinations rather than artistic vision—even though they are only available to us as a result of textual strategies. More generally, the aural and visual evidence of what ten years of hard

Fred Wiseman's Models

(Zipporah Films, One Richdale Avenue, Unit #4, Cambridge, MA 02140)

living do to the alert, mischievous appearance of two boys—the ruddy skin, the dark, extinguished eyes, the slurred and garbled speech, especially of Stoffe—bear meaning precisely because the films invite retroactive comparison. The films produce the structure in which "facts" themselves take on meaning precisely because they belong to a coherent series of differences. Yet, though powerful, this construction of differences remains insufficient. A simplistic line of historical progression prevails, centered as it is in Soldier Girls on the trope of romantic individualism. (Instead of the Great Man theory we have the Unfortunate Victim theory of history—inadequate, but compellingly presented.)

And where observational cinema shifts from an individual to an institutional focus, and from a metonymic narrative model to a metaphoric one, as in the highly innovative work of Fred Wiseman, there may still be only a weak sense of constructed meaning, of a textual voice addressing us. A vigorous, active, and retroactive reading is necessary before we can hear the voice of the textual system as a level distinct from the sounds and images of the evidence it adduces, while questions of adequacy remain. Wiseman's sense of context and of meaning as a function of the text itself remains weak, too easily engulfed by the fascination that allows us to mistake film for reality, the impression of the real for the experience of it. The risk of reading Soldier Girls or Wiseman's Models like a Rorschach test may require stronger counter-measures than the subtleties their complex editing and mise-en-scène provide.

Prompted, it would seem, by these limitations to cinéma vérité or observational cinema, many film-makers during the past decade have reinstituted direct address. For the most part this has meant social actors addressing us in interviews rather

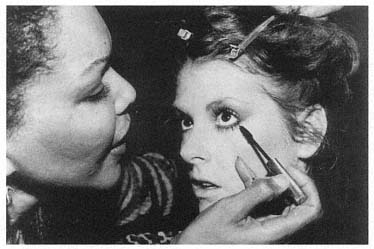

than a return to the voice-of-authority evidenced by a narrator. Rosie the Riveter , for example, tells us about the blatant hypocrisy with which women were recruited to the factories and assembly lines during World War II. A series of five women witnesses tell us how they were denied the respect granted men, told to put up with hazardous conditions "like a man," paid less, and pitted against one another racially. Rosie makes short shrift of the noble icon of the woman worker as seen in forties newsreels. Those films celebrated her heroic contribution to the great effort to preserve the free world from fascist dictatorship. Rosie destroys this myth of deeply appreciated, fully rewarded contribution without in any way undercutting the genuine fortitude, courage, and political awareness of women who experienced continual frustration in their struggles for dignified working conditions and a permanent place in the American labor force.

Using interviews, but no commentator, together with a weave of compilation footage as images of illustration, director Connie Field tells a story many of us may think we've heard, only to realize we've never heard the whole of it before.

The organization of the film depends heavily on its set of extensive interviews with former "Rosies." Their selection follows the direct-cinema tradition of filming ordinary people. But Rosie the Riveter broadens that tradition, as Union Maids, The Wobblies , and With Babies and Banners have also done, to retrieve the memory of an "invisible" (suppressed more than forgotten) history of labor struggle. The five interviewees remember a past the film's inserted historical images reconstruct, but in counterpoint: their recollection of adversity and struggle contrasts with old newsreels of women "doing their part" cheerfully.

This strategy complicates the voice of the film in an interesting way. It adds a contemporary, personal resonance to the historical compilation footage without challenging the assumptions of that footage explicitly, as a voice-over commentary might do. We ourselves become engaged in determining how the women witnesses counterpoint these historical "documents" as well as how they articulate their own present and past consciousness in political, ethical, and feminist dimensions.

We are encouraged to believe that these voices carry less the authority of historical judgment than that of personal testimony—they are, after all, the words of apparently "ordinary women" remembering the past. As in many films that advance issues raised by the women's movement, there is an emphasis on individual but politically significant experience. Rosie demonstrates the power of the act of naming—the ability to find the words that render the personal political. This reliance on oral history to reconstruct the past places Rosie the Riveter within what is probably the predominant mode of documentary film-making today—films built around a string of interviews—where we also find A Wive's Tale, With Babies and Banners, Controlling Interest, The Day After Trinity, The Trials of Alger Hiss, Rape, Word Is Out, Prison

Rosie the Riveter

(Clarity Films, 2600 10th St., Ste. 412, Berkeley, CA 94710)

for Women, Not a Love Story, Nuove Frontieras (Looking for Better Dreams) , and The Wobblies .

This reinstitution of direct address through the interview has successfully avoided some of the central problems of voice-over narration, namely authoritative omniscience or didactic reductionism. There is no longer the dubious claim that things are as the film presents them, organized by the commentary of an all-knowing subject. Such attempts to stand above history and explain it create a paradox. Any attempt by a speaker to vouch for his or her own validity reminds us of the Cretan paradox: "Epimenides was a Cretan who said, 'Cretans always lie.' Was Epimenides telling the truth?" The nagging sense of a self-referential claim that can't be proven reaches greatest intensity with the most forceful assertions, which may be why viewers are often most suspicious of what an apparently omniscient Voice of Authority asserts most fervently. The emergence of so many recent documentaries built around strings of interviews strikes me as a strategic response to the recognition that neither can events speak for themselves nor can a single voice speak with ultimate authority.

Interviews diffuse authority. A gap remains between the voice of a social actor recruited to the film and the voice of the film.

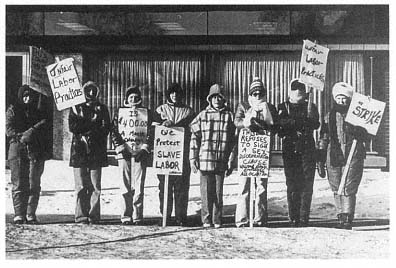

Not compelled to vouch for their own validity, the voices of interviewees may well arouse less suspicion. Yet a larger, constraining voice may remain to provide, or withhold, validation. In The Sad Song of Yellow Skin, The Wilmar 8, Harlan County, USA, Not a Love Story , or Who Killed the Fourth Ward , among others, the literal voice of the film-maker enters into dialogue but without the self-validating, authoritative tone of a previous tradition. (These are also voices without the self-reflexive quality found in Vertov's, Rouch's, or the MacDougalls' work.) Diary-like and uncertain in Yellow Skin ; often directed toward the women strikers as though by a fellow participant and observer in The Wilmar 8 and Harlan County; sharing personal reactions to pornography with a companion in Not a Love Story; and adopting a mock ironic tone reminiscent of Peter Falk's Columbo in Fourth Ward —these voices of potentially imaginary assurance instead share doubts and emotional reactions with other characters and us. As a result they seem to refuse a privileged position in relation to other characters. Of course, these less assertive authorial voices remain complicit with the controlling voice of the textual system itself, but the effect upon a viewer is distinctly different.

Still, interviews pose problems. Their occurrence is remarkably widespread—from The Hour of the Wolf to The MacNeil/Lehrer Report and from Housing Problems (1935) to Harlan County, USA . The greatest problem, at least in recent documentary, has been to retain that sense of a gap between the voice of interviewees and the voice of the text as a whole. It is most obviously a problem when the interviewees display conceptual inadequacy on the issue but remain unchallenged by the film. The Day After Trinity , for example, traces Robert F. Oppenheimer's career but restricts itself to a Great Man theory of history. The string of interviews clearly identify Oppenheimer's role in the race to build the nuclear bomb, and his equivocations, but it never places the bomb or Oppenheimer within that larger constellation of government policies and political calculations that determined its specific use or continuing threat—even though the interviews took place in the last few years. The text not only appears to lack a voice or perspective of its own, the perspective of its character-witnesses is patently inadequate.

In documentary, when the voice of the text disappears behind characters who speak to us, we confront a specific strategy of no less ideological importance than its equivalent in fiction films. When we no longer sense that a governing voice actively provides or withholds the imprimatur of veracity according to its own purposes and assumptions, its own canons of validation, we may also sense the return of the paradox and suspicion that interviews should help us escape: the word of witnesses, un-

The Wilmar 8

(California Newsreel, 149 9th St., San Francisco, CA 94103)

critically accepted, must provide its own validation. Meanwhile, the film becomes a rubber stamp. To varying degree this diminution of a governing voice occurs through parts of Word Is Out, The Wobblies, With Babies and Banners , and Prison for Women . The sense of a hierarchy of voices becomes lost.[5] Ideally this hierarchy would uphold correct logical typing at one level (the voice of the text remains of a higher, controlling type than the voices of interviewees) without denying the inevitable collapse of logical types at another (the voice of the text is not above history but part of the very historical process upon which it confers meaning). But at present a less complex and less adequate sidetracking of paradox prevails. The film says, in effect, "Interviewees never lie." Interviewees say, "What I am telling you is the truth." We then ask, "Is the interviewee telling the truth?" but find no acknowledgement in the film of the possibility, let alone the necessity, of entertaining this question as one inescapable in all communication and signification.

As much as anyone, Emile de Antonio, who pioneered the use of interviews and compilation footage to organize complex historical arguments without a narrator, has also provided clear signposts for avoiding the inherent dangers of interviews. Unfortunately, most of the film-makers adopting his basic approach have failed to heed them.

De Antonio demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of the category of the personal. He does not invariably accept the word of witnesses, nor does he adopt rhetorical strategies (Great Man theories, for example) that limit historical understanding to the personal. Something exceeds this category,

and in Point of Order, In the Year of the Pig, Milhouse: A White Comedy , and Weather Underground , among others, this excess is carried by a distinct textual voice that clearly judges the validity of what witnesses say. Just as the voice of John Huston in The Battle of San Pietro contests one line of argument with another (that of General Mark Clark, who claims the costs of battle were not excessive, with that of Huston, who suggests they were), so the textual voice of de Antonio contests and places the statements made by its embedded interviews, but without speaking to us directly. (In de Antonio and in his followers, there is no narrator, only the direct address of witnesses.)

This contestation is not simply the express support of some witnesses over others, for left against right. It is a systematic effect of placement that retains the gaps between levels of different logical type. De Antonio's overall expository strategy in In the Year of the Pig , for example, makes it clear that no one witness tells the whole truth. De Antonio's voice (unspoken but controlling) makes witnesses contend with one another to yield a point of view more distinctive to the film than to any of its witnesses (since it includes this very strategy of contention). (Similarly, the unspoken voice of The Atomic Cafe —evident in the extraordinarily skillful editing of government nuclear weapons propaganda films from the fifties—governs a preferred reading of the footage it compiles.) But particularly in de Antonio's work, different points of view appear. History is not a monolith, its density and outline given from the outset. On the contrary, In the Year of the Pig , for example, constructs perspective and historical understanding, and does so right before our eyes.

We see and hear, for example, U.S. government spokesmen explaining their strategy and conception of the "Communist menace," whereas we do not see and hear Ho Chi Minh explain his strategy and vision. Instead, an interviewee, Paul Mus, introduces us to Ho Chi Minh descriptively while de Antonio's cut-aways to Vietnamese countryside evoke an affiliation between Ho and his land and people that is absent from the words and images of American spokesmen. Ho remains an uncontained figure whose full meaning must be conferred, and inferred, from available materials as they are brought together by de Antonio. Such construction is a textual, and cinematic, act evident in the choice of supporting or ironic images to accompany interviews, in the actual juxtaposition of interviews, and even in the still images that form a pre-credit sequence inasmuch as they unmistakably refer to the American Civil War (an analogy sharply at odds with U.S. government accounts of Communist invasion). By juxtaposing silhouettes of Civil War soldiers with GIs in Vietnam, the pre-credit sequence obliquely but clearly offers an interpretation for the events we are about to see. De Antonio does not subordinate his own voice to the way things are, to the sounds and images that are evidence of war. He acknowledges that the meaning of these images must be conferred upon them and goes about doing so in a readily understood though indirect manner.

In the Year of the Pig

De Antonio's hierarchy of levels and reservation of ultimate validation to the highest level (the textual system or film as a whole) differs radically from other approaches. John Lowenthal's The Trials of Alger Hiss , for example, is a totally subservient endorsement of Hiss's legalistic strategies. Similarly, Hollywood on Trial shows no independence from the perhaps politically expedient but disingenuous line adopted by the Hollywood 10 over thirty years ago—that HUAC's pattern of subpoenas to friendly and unfriendly witnesses primarily threatened the civil liberties of ordinary citizens (though it certainly did so) rather than posing a more specific threat to the CPUSA and American left (where it clearly did the greatest damage). By contrast, even in Painters Painting and Weather Underground , where de Antonio seems unusually close to validating uncritically what interviewees say, the subtle voice of his mise en scène preserves the gap, conveying a strong sense of the distance between the sensibilities or politics of those interviewed and those of the larger public to whom they speak.

De Antonio's films produce a world of dense complexity: they embody a sense of constraint and over-determination. Not everyone can be believed. Not everything is true. Characters do not emerge as the autonomous shapers of a personal destiny. De Antonio proposes ways and means by which to reconstruct the past dialectically, as Fred Wiseman reconstructs the present dialectically.[6]

Rather than appearing to collapse itself into the consciousness of character witnesses, the film retains an independent consciousness, a voice of its own. The film's own consciousness (surrogate for ours) probes, remembers, substantiates, doubts. It questions and believes, including itself. It assumes the voice of personal consciousness at the same time as it examines the very category of the personal. Neither omniscient deity nor obedient mouthpiece, de Antonio's rhetorical voice seduces us by embodying those qualities of insight, skepticism, judgment, and independence we would like to appropriate for our own. Nonetheless, though he is closer to a modernist, self-reflexive strategy than any other documentary film-maker in America—with the possible exception of the more experimental feminist film-maker JoAnn Elam—de Antonio remains clearly apart from this tendency. He is more a Newtonian than an Einsteinian observer of events; he insists on the activity of fixing meaning, but it is meaning that does, finally, appear to reside "out there" rather than insisting on the activity of producing that "fix" from which meaning itself derives.

There are lessons here we would think de Antonio's successors would be quick to learn. But, most frequently, they have not. The interview remains a problem. Subjectivity, consciousness, argumentative form, and voice remain unquestioned in documentary theory and practice. Often, film-makers simply choose to interview characters with whom they agree. A weaker sense of skepticism, a diminished self-awareness of the film-maker as producer of meaning or history prevails, yielding a flatter, less dialectical sense of history and a simpler, more idealized sense of character. Characters threaten to emerge as stars—flashpoints of inspiring, and imaginary, coherence contradictory to their ostensible status as ordinary people.[7]

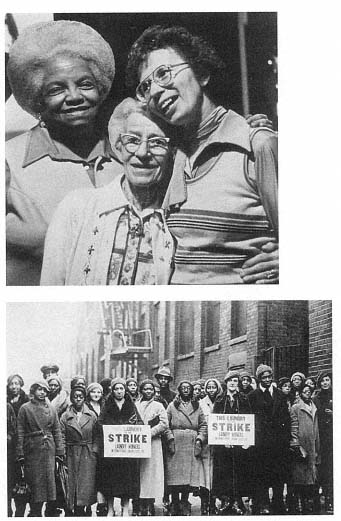

These problems emerge in three of the best history films we have (and in the pioneering gay film, Word Is Out ), undermining their great importance on other levels. Union Maids, With Babies and Banners , and The Wobblies flounder on the axis of personal respect and historical recall. The films simply suppose that things were as the participant-witnesses recall them, and lest we doubt, the film-makers respectfully find images of illustration to substantiate the claim. (The resonance set up in Rosie the Riveter between interviews and compilation footage establishes a perceptible sense of a textual voice that makes this film a more sophisticated, though not self-reflexive, version of the interview-based documentary.) What characters omit to say, so do these films, most noticeably regarding the role of the CPUSA in Union Maids and With Babies and Banners. Banners , for example, contains one instance when a witness mentions the helpful knowledge she gained from Communist Party members. Immediately, though, the film cuts to unrelated footage of a violent attack on workers by a goon squad. It is as if the textual voice, rather than provide independent assessment, must go so far as to find diversionary material to offset presumably harmful comments by witnesses themselves!

Union Maids

These films naively endorse limited, selective recall. The tactic flattens witnesses into a series of imaginary puppets conforming to a line. Their recall becomes distinguishable more by differences in force of personality than by differences in perspective. Backgrounds loaded with iconographic meanings transform witnesses further into stereotypes (shipyards, farms, union halls abound, or for the gays and lesbians in Word Is Out , bedrooms and the bucolic out-of-doors). We sense a great relief when characters step out of these closed, iconographic frames and into more open-ended ones, but such "release" usually occurs only at the end of the films where it also signals the achievement of expository closure—another kind of frame. We return to the simple claim, "Things were as these witnesses describe them, why contest

them?"—a claim which is a dissimulation and a disservice to both film theory and political praxis. On the contrary, as de Antonio and Wiseman demonstrate quite differently, Things signify, but only if we make them comprehensible.[8]

Documentaries with a more sophisticated grasp of the historical realm establish a preferred reading by a textual system that asserts its own voice in contrast to the voices it recruits or observes. Such films confront us with an alternative to our own hypotheses about what kind of things populate the world, what relations they sustain, and what meanings they bear for us. The film operates as an autonomous whole, as we do. It is greater than its parts and orchestrates them: (1) the recruited voices, the recruited sounds and images; (2) the textual "voice" spoken by the style of the film as a whole (how its multiplicity of codes, including those pertaining to recruited voices, are orchestrated into a singular, controlling pattern); and (3) the surrounding historical context, including the viewing event itself, which the textual voice cannot successfully rise above or fully control. The film is thus a simulacrum or external trace of the production of meaning we undertake ourselves every day, every moment. We see not an image of imaginary unchanging coherence, magically represented on a screen, but the evidence of an historically rooted act of making things meaningful comparable to our own historically situated acts of comprehension.

With de Antonio's films, The Atomic Cafe, Rape , or Rosie the Riveter , the active counterpointing of the text reminds us that its meaning is produced. This foregrounding of an active production of meaning by a textual system may also heighten our conscious sense of self as something also produced by codes that extend beyond ourselves. An exaggerated claim, perhaps, but still suggestive of the difference in effect of different documentary strategies and an indication of the importance of the self-reflexive strategy itself.

Self-reflexiveness can easily lead to an endless regression. It can prove highly appealing to an intelligentsia more interested in "good form" than in social change. Yet interest in self-reflexive forms is not purely an academic question. Cinéma vérité and its variants sought to address certain limitations in the voice-of-God tradition. The interview-oriented film sought to address limitations apparent in the bulk of cinéma vérité , and the self-reflexive documentary addresses the limitations of assuming that subjectivity and both the social and textual positioning of the self (as filmmaker or viewer) are ultimately not problematic.

Modernist thought in general challenges this assumption. A few documentary filmmakers, going as far back as Dziga Vertov and certainly including Jean Rouch and the hard-to-categorize Jean-Luc Godard, adopt the basic epistemological assumption in their work that knowledge and the position of the self in relation to the mediator of knowledge, a given text, are socially and formally constructed and should be shown to be so. Rather than inviting paralysis before

a centerless labyrinth, however, such a perspective restores the dialectic between self and other: neither the "out there" nor the "in here" contains its own inherent meaning. The process of constructing meaning overshadows constructed meanings. And at a time when modernist experimentation is old-hat within the avant-garde and a fair amount of fiction film-making, it remains almost totally unheard of among documentary film-makers, especially in North America. It is not political documentarists who have been the leading innovators. Instead it is a handful of ethnographic film-makers like Timothy Asch (The Ax Fight ), John Marshall (Nai! ), and David and Judith MacDougall who, in their meditations on scientific method and visual communication, have done the most provocative experimentation.

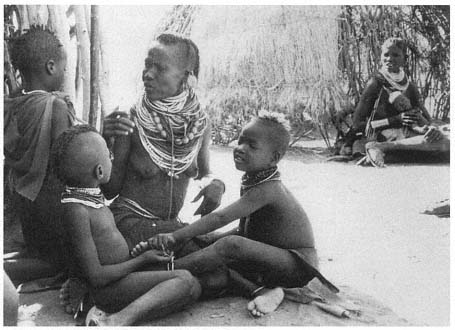

Take the MacDougalls' Wedding Camels (part of the Turkana trilogy), for example. The film, set in Northern Kenya, explores the preparations for a Turkana wedding in day-to-day detail. It mixes direct and indirect address to form a complex whole made up of two levels of historical reference—evidence and argument—and two levels of textual structure—observation and exposition.

Though Wedding Camels is frequently observational and very strongly rooted in the texture of everyday life, the film-makers' presence receives far more frequent acknowledgment than it does in Soldier Girls , or Wiseman's films, or most other observational work. Lorang, the bride's father and central figure in the dowry negotiations, says at one point, with clear acknowledgment of the film-makers' presence, "They [Europeans] never marry our daughters. They always hold back their animals." At other moments we hear David MacDougall ask questions of Lorang or others off-camera much as we do in The Wilmar 8 or In the Year of the Pig . (This contrasts with The Wobblies, Union Maids , and With Babies and Banners , where the questions to which participant-witnesses respond are not heard.) Sometimes these queries invite characters to reflect on events we observe in detail, like the dowry arrangements themselves. On these occasions they introduce a vivid level of self-reflexiveness into the characters' performance as well as into the film's structure, something that is impossible in interview-based films that give us no sense of a character's present but only use his or her words as testimony about the past.

Wedding Camels also makes frequent use of intertitles which mark off one scene from another to develop a mosaic structure that necessarily admits to its own lack of completeness even as individual facets appear to exhaust a given encounter. This sense of both incompleteness and exhaustion, as well as the radical shift of perceptual space involved in going from apparently three-dimensional images to two-dimensional graphics that comment on or frame the image, generates a strong sense of a hierarchical and self-referential ordering.

Wedding Camels

For example, in one scene Naingoro, sister to the bride's mother, says, "Our daughters are not our own. They are born to be given out." The implicit lack of completeness to individual identity apart from social exchange then receives elaboration through an interview sequence with Akai, the bride. The film poses questions by means of intertitles and sandwiches Akai's responses, briefly, between them. One intertitle, for example, phrases its question more or less as follows: "We asked Akai whether a Turkana woman chooses her husband or if her parents choose for her." Such phrasing brings the filmmaker's intervention strongly into the foreground.

The structure of this passage suggests some of the virtues of a hybrid style: the titles serve as another indicator of a textual voice apart from that of the characters represented. They also differ from most documentary titles which, since the silent days of Nanook , have worked like a graphic "voice" of authority. In Wedding Camels the titles, in their mock-interactive structure, remain closely aligned with the particulars of person and place rather than appearing to issue from an omniscient consciousness. They show clear awareness of how a particular meaning is being produced by a particular act of intervention. This is not presented as

a grand revelation but as a simple truth that is only remarkable for its rarity in documentary film. These particular titles also display both a wry sense of humor and a clear perception of the meaning an individual's marriage has for him or her as well as for others (a vital means of countering, among other things, the temptation of an ethnocentric reading or judgment). By "violating" the coherence of a social actor's diegetic space, intertitles also lessen the tendency for the interviewee to inflate to the proportions of a star-witness. By acting self-reflexively such strategies call the status of the interview itself into question and diminish its tacit claim to tell the whole truth. Other signifying choices, which function like Brechtian distancing devices, would include the separate "spaces" of image and intertitle for question/response; the highly structured and abbreviated question/answer format; the close-up, portrait-like framing of a social actor that pries her away from a matrix of on-going activities or a stereotypical background, and the clear acknowledgment that such fabrications exist to serve the purposes of the film rather than to capture an unaffected reality.

Though modest in tone, Wedding Camels demonstrates a structural sophistication well beyond that of almost any other documentary film work today. Whether its modernist strategies can be yoked to a more explicitly political perspective (without restricting itself to the small avant-garde audience that exists for the Godards and Chantal Akermans) is less a question than a challenge still haunting us, considering the limitations of most interview-based films.

Changes in documentary strategy bear a complex relation to history. Self-reflexive strategies seem to have a particularly complex historical relation to documentary form since they are far less peculiar to it than the voice-of-God, cinéma vérité , or interview-based strategies. Although they have been available to documentary (as to narrative) since the 'teens, they have never been as popular in North America as in Europe or in other regions (save among an avant-garde). Why they have recently made an effective appearance within the documentary domain is a matter requiring further exploration. I suspect we are dealing with more than a reaction to the limitations of the currently dominant interview-based form. Large cultural preferences concerning the voicing of dramatic as well as documentary material seem to be changing. In any event, the most recent appearances of self-reflexive strategies correspond very clearly to deficiencies in attempts to translate highly ideological, written anthropological practices into a proscriptive agenda for a visual anthropology (neutrality, descriptiveness, objectivity, "just the facts," and so on). It is very heartening to see that the realm of the possible for documentary film has now expanded to include strategies of reflexivity that may eventually serve political as well as scientific ends.

Newsreel:

Old and New—Towards an Historical Profile

Michael Renov

Our films remind some people of battle footage: grainy, camera weaving around trying to get the material and still not get beaten/trapped. Well, we and many others, are at war. We not only document that war, but try to find ways to bring that war to places which have managed so far to buy themselves isolation from it. . . . Our propaganda is one of confrontation. Using film—using our voices with and after films—using our bodies with and without camera—to provoke confrontation. . . . Therefore we keep moving. We keep hacking out films, as quickly as we can, in whatever way we can.

Robert Kramer, New York Newsreel, 1968[1]

Documentary remains the major form of political filmmaking in this country. It has always been and probably will be in the foreseeable future. And yet, there has been very, very little discussion of how documentary films actually function. The political efficacy of documentary is derived from the relationship of the audience to the film—not the relationship of the filmmaker to the subject.

Larry Daressa, California Newsreel, 1983[2]

Vol. 41, no. 1 (Fall 1987): 20–33.

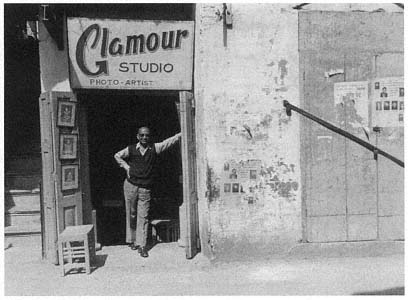

December 1987 will mark the twenty-year anniversary of the formation of Newsreel, a radical film-making collective conceived during the last flush of New Left activism. Once boasting offices in New York, San Francisco, Boston, Los Angeles, Detroit, Chicago, and Atlanta, Newsreel now survives in two versions: California Newsreel, San Francisco, producers and distributors of films about the workplace as well as South Africa and apartheid, with a new focus on media education (educating Americans about rather than through media); and Third World Newsreel, New York, vortex of film and video activities intended as the cultural interventions of the disenfranchised. In the following pages, I hope to suggest areas of conceptual as well as functional continuity and discontinuity between the two extant Newsreel organizations, as well as between the present enterprises and their Newsreel predecessors. In doing so, I seek to draw attention both to the achievements of a generation of American film activists and to the necessarily altered requirements for survival for politically committed documentarists in the late eighties. An historical profile of this sort can only point to a few of the most dramatic tendencies across decades of activity; this account will be supplemented by the soon-to-be-updated Third World Newsreel catalogue featuring descriptions of the Newsreel films in circulation (in addition to the hundred or so independently produced films and tapes they distribute) and by more in-depth accounts of the Newsreel infrastructure and output during its several phases.[3]

Newsreel Pre-history

The counterculture of the New Left tended toward negation, the issuing of shocks against presumed middle-class sensibilities, all the while reinforcing oppositional ties. Consequently, one must look elsewhere than to the culture of the American Left of the thirties for radical antecedents, perhaps to the Surrealist or

Columbia Revolt (1968): one of Newsreel's first films

Constructivist positions earlier in the century. If one may judge from the rhetoric of first-generation Newsreelers such as Robert Kramer, it is the utopian socialism of the immediately post-revolutionary Soviet Union that resonates most deeply with the cultural radicalism of the New Left, not the populist humanism of the American thirties.

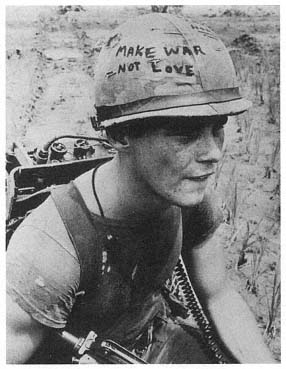

It is the combination of youthfulness, enthusiasm, and volatility that links the work and writing of Dziga Vertov with the first wave of Newsreel practitioners. Both were dedicated to the concept of a continuing revolution and the potential of the cinema to mobilize a shared political identity necessary for broad-based social change. What separates the two and forces us to pose them in dialectical tension are their respective relations to state power and to technology. Vertov and his comrades worked at the cutting edge of a state-run revolution. Newsreel was a manifestation of the counterculture, defining itself always in opposition to the dominant, generating and encouraging resistance to the authority of the prevailing system of social, political, and economic relations.[4]

Vertov, trained as were so many other Soviet film artists for a scientific vocation, envisioned cinema as a technological vehicle for extending human powers of observation and cognition. His kinoki were labelled as "pilots" or "engineers" whose machine eye and radio ear could transform history. A child of his time, Vertov praised the beauty and perfection of the mechanical world and of chemical processes as the triumphant extension of natural forces.

A half-century later, the relationship of New Left media activists to technology was chiefly one of negation. Early Newsreelers harbored little hope of appropriating or re-routing channels of communication to further their political goals. ("None of us are old enough to have any illusions about infiltrating the major media to reach mass consciousness and change it—we grew up on TV and fifties Hollywood."[5] ) Unlike Vertov and his kinoki , or even the American Old Left, the founders of Newsreel in late 1967 could claim no institutional or mass-based source of support. Rather, as suggested earlier, mass base had become mass culture; party was replaced by a constituency-in-media. And yet, as with Vertov, there was within the early Newsreel movement a feverish impulse toward an elemental reconstruction for its audience—if not of perception, at least of consciousness. These radical cineastes were inspired by the enforced aesthetic privations of true guerrilla footage, documents of forces fighting wars of liberation in Vietnam, Africa, or Latin America, or by the pre-industrialized methods of the American underground film, which also offered refuge from the seamless, ideologically complicit products of the culture industry.

There is a further point of historical tangency between early Newsreel and Vertov's efforts in the pre-dawn of radical cinema. Just as the Soviet agittrains, armed with camera equipment, film lab, and projector, traversed the land from 1919 to 1921 helping to forge a nascent cultural identity, so too did early Newsreelers mobilize their own community outreach program. Recent Academy Award recipient Deborah Shaffer (Witness to War , 1985) has spoken of the methods of distribution and exhibition in the Ann Arbor, Michigan chapter of Newsreel in 1969–70:

We had two motorcycles and we put this box on the back of the motorcycle to hold the projector. We'd go off on motorcycles with the projector and films. We would show them in dormitories, churches, people's living rooms, union halls, high school auditoriums.[6]

Vertov and his New Left cousins shared the zeal and inventiveness of the bricoleur-evangelist.

The reconstruction of consciousness for the Newsreel audience was to be achieved by a willed abdication from the standards of quality or craft; the intention was a return to an essential cinema dedicated to the requirements of building an adversarial culture. The simplicity of the appellation "Newsreel" figures a desire for a fundamental reinscription of values and practices. The unstinting revisionism which underlies this naming and its return to the blank slate of historical representation is an act of both youthful bravery and of a willing forgetfulness which breaks ties with a set of complex histories. The

popular frontism of the American Left in the late 1930s and early 1940s was rooted in a hope of base-building and eventual unification while the political radicalisms of the late 1960s implied a contrary motive—the intensification of social contradiction to the point of rupture. For while the founding membership of Newsreel in New York included a core of veterans of mid-sixties community-organizing campaigns, the organization was forged in a moment of communal anger and indignation following the October 1967 March on the Pentagon. The agenda for a grass-roots, participatory democracy was buckling under the weight of a growing militancy.[7]

The altered agenda of an increasingly apocalyptic moment is expressed quite succinctly in Garbage (Newsreel, 1968), a film which examines a planned provocation by the members of a New York anarchist group calling itself "Up Against the Wall, Motherfuckers." During a prolonged strike of garbage collection workers, the Motherfuckers devise a plan to bring rotting garbage to the bastions of high culture and political power. They therefore dump enormous heaps of trash at the entrance-ways of Lincoln Center, home of the Metropolitan Opera and New York Philharmonic Symphony. As footage of this confrontation unspools, one demonstrator observes in voice-over that the difference between the Old Left and the New is expressed by their differing approaches to problems—the former sought to solve them, the latter to intensify them.

Institutional Ties—The Myth of Creation

As interviews with early New York Newsreel members indicate, the first generation of this radical film-making group represented a convergence of disparate impulses and constituencies.[8] There were the former SDS activists whose political sensibilities had been forged through a decade of community-based activism and programmatic wrangling. Of this number, Robert Kramer and Norm Fruchter, with his ties to such influential journals as Studies on the Left and New Left Review , remain the prototypes. These were the ideologues, the political "heavies" whose Movement credentials and rhetorical skills were capable of intimidating opposition in mass meetings. In addition, there were the "underground" film-makers whose concerns were loosely tied to notions of alternative art-making and self-expression, products of the boom period of the New American Cinema when the Brakhages and the Baillies commanded a sizable audience in the museums and on the campuses. The former Newsreel faction was likely to give priority to the construction of correct political organizations expressed in filmic terms while the latter tendency defined itself more directly in terms of its craft, guided by political concerns but not subsumed by them. This is, of course, a rough approximation or profile of some forty or

fifty people whose idiosyncracies tended to obscure any such general tendencies.[9]

There is a larger and quite striking commonality decipherable, however; neither faction could claim for itself an organized or structurally coherent base of support—in short, an audience. Neither the Marxists nor the underground film-makers could presume to know their constituencies in any but the most abstract terms, the political activists because the Movement was undergoing a painful process of fragmentation typified by the SDS splits while the film artisans were rooted in a tradition of expressivity which valued the isolation of the artist within the hegemony of mass culture. The very values which united every Newsreel audience or potential audience were based on a fundamental negation of institutionalized frameworks (alienation from accepted social and political forms, cynicism toward the trade unionism that had been the bastion of the Old Left, a preference for vaguely articulated rather than explicit associations). A politically inflected cultural group like Newsreel, in bearing what Bill Nichols has characterized as a barometric relationship to the Left,[10] could only reproduce the soft boundaries and conceptual dissonance of late sixties political dissent typified by the rainbow of orientations and agendas that combined to protest the 1968 Chicago Democratic Convention—from the Dave Dellinger–style anti-war pacifists to the anarchic Yippie contingent.

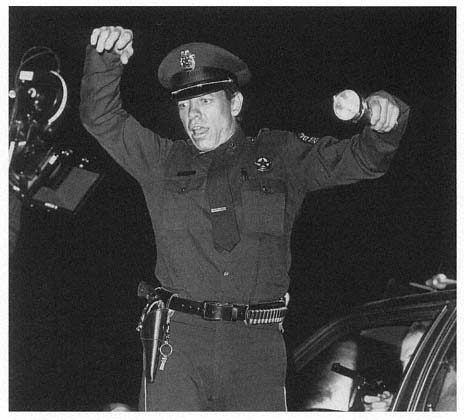

Despite the conceptual pluralism of Newsreel's position in the early years, we can discern certain frequently unstated premises of the organization. From an interview with a range of Newsreelers published in a 1968 Film Quarterly , Marilyn Buck and Karen Ross gave voice to the mythic origins of the collective: "And all the TV channels and American films speak from the same mouth of control and power. We looked around . . . and Newsreel was conceived and born."[11] There is the suggestion of a kind of autochthony here, of a cleansing oracle arisen from within the belly of the mass-cultural beast. The two films which catapulted Newsreel to success in countercultural terms (Columbia Revolt, Black Panther —both 1968) offer further evidence of such a mythos of spontaneous generation. The films share an aura of revolutionary romanticism, offering direct contact with what appeared at the time to be the most advanced elements of the struggle—in short, news from the front. The Panther film, alternately titled Off the Pig (a phrase hypnotically chanted by a phalanx of Panthers during a demonstration at the Alameda County Courthouse), brought the words and images of Huey P. Newton, Eldridge Cleaver, and Bobby Seale to Movement audiences everywhere. More importantly, by its mise-en-scène and incantatory music track accompanying bereted and leather-jacketed Panthers-in-training, the film manages to suggest a great deal more than it can show. "No more brothers in jail/The pigs are gonna catch hell" sing the militant brothers and sisters while Cleaver speaks of the bald-headed businessmen in the

Chamber of Commerce whose exploitation will be countered by mass insurgency as soon as the rest of America catches on (which Cleaver assures us will be very soon). Here is a mixture of buoyant militancy and a political optimism which is well nigh infectious—or would have been for a sympathetic 1968 audience. In any case, hundreds of prints sold in a matter of months.

As for Columbia Revolt , one need only consult the published responses of student audiences to be found in the underground press of the day. According to an October 1969 account appearing in Rat , a New York–based organ of the radical counterculture, Revolt was responsible for an incendiary outburst at a college campus in Buffalo: "At the end of the second film, with no discussion, five hundred members of the audience arose and made their way to the University ROTC building [the Reserve Officer Training Corps, target of much campus protest during the Vietnam War]. They proceeded to smash windows, tear up furniture and destroy machines until the office was a total wreck; and then they burned the remaining paper and flammable parts of the structure to charcoal."[12] What the Buffalo student body had observed (and the apocryphal nature of the tale is no hindrance to a discussion of mythic contours) was the vanguard action of their Ivy League cousins, a model of energetic but sustained resistance to malign authority. The analysis contained in Columbia Revolt is muted in comparison to the spectacle of solidarity and community it offers. The New Age marriage rites of two students, the support marches of sympathetic faculty members, the pitch-and-catch of food stuffs holding intact the supply lines which, like the Ho Chi Minh Trail, meant sustenance for the guerrillas under siege—all these depictions of newly conceived social relations live on long after the immediate gymnasium construction issue is forgotten.

The efforts of the early Newsreel collectives aimed to inform and inspire their Movement audiences, with the balance between the two functions always in question. While a pre-Newsreel film like Troublemakers (1966), which follows the struggles of a community organizing group in a black neighborhood in Newark before the riots (examining the project's achievements and defeats), explores the contradictions inherent in grass-roots political activism, the post'68 Newsreel film was likely to stress action and elicit engaged (if not educated) response. In a pronouncement that echoes the Surrealist position of the 1920s, Robert Kramer outlined the Newsreel program circa 1968: "We strive for confrontation, we prefer disgust/violent disagreement/painful recognition/jolts—all these to slow liberal head-nodding and general wonderment at the complexity of these times and their being out of joint."[13]

Given the avowedly confrontational status of the work, the emphasis upon a collective scheme of organization and production ("Newsreel is a collective rather than a cooperative; we are not together merely to help each other out

Columbia Revolt

as filmmakers but we are working together for a common purpose"),[14] what can be said about the precise division of labor of the groups in question and the material conditions of production? As every Marxist knows, consciousness does not anticipate productive relations but is conditioned and determined by them. But a major philosopher of the New Left like Herbert Marcuse was quite willing to theorize (in An Essay on Liberation , 1969) that, in a stage of advanced capitalism, imagination could show reason the way. Artists and free-thinkers could reshape the horizons of a society soured and desensitized by an over-rationalized ethos of thought and action. As a loosely bound group of like-minded cultural interventionists, Newsreel was the ideal manifestation of this New Age dogma.

Decision-making and the setting of policy were matters of some contestation given the lack of clear lines of authority and the diverse backgrounds of the participants. At a time that felt like a crisis period, specific goals (even ill-defined ones like "stop the war") offered sufficient binding power to keep the wheels turning and the Movement audience served. Those who, like Norm Fruchter, were accustomed to a greater precision of shared principles and a more disciplined group dynamic found the Newsreel experience a trying one. "I was . . . more of a Marxist, I think, than a lot of people in Newsreel," says Fruchter, "and so I was both interested in those congeries of different folks, and at the same time skeptical about whether we were going to hold together. The energy was awesome."[15]

So far as the mechanism for production decisions was concerned, the pattern was erratic at best. The most fundamental decisions always surrounded the initial question—what films should be made. But a second question—how to finance a given project—often proved determinant. Films could be made if there

were those within the collective who could manage to make them by whatever means might present themselves. If the final result was unacceptable to the group, the film could not receive the "Newsreel" imprimatur. Several funding routes seem to have recurred in the early days. There was a core elite within the New York collective who matched the profile of the SDS leadership throughout the sixties—college-educated white males, verbal, assertive, confident, with access to funding sources both personal and institutional. Robert Kramer and Robert Machover could call upon family resources to finance projects. (Indeed, this pattern is a time-honored one in American Left circles, most recently exemplified by Haskell Wexler's anti-Contra feature, Latino —bankrolled in part by his mother.) The Fruchters, Kramers, and Machovers of Newsreel were the bright and persuasive young men who could function within the world of capital, either by virtue of birthright or by acquired expertise. Fruchter, for example, was well suited for fundraising given his scholarly and literary credentials (as a published novelist) and his first-hand experience with Left funding networks. Fruchter has estimated that he succeeded in raising more money for Troublemakers , his film about the Newark Community Union Project, than had the Project itself over its several-year lifespan. There were simmering animosities over this relative monopoly of capital-access, rooted as it was in class background. Furthermore, this same group of men (who were a key faction of the New York collective's coordinating committee) possessed far greater technical skills and experience; Fruchter, Kramer, and Machover had formed Blue Van Films several years before.

A second faction consisted of yet another group of white males who, though less likely candidates for institutional support, were well under way as independent film-makers. By 1968, Marvin Fishman and Allan Siegel had both organized film-making workshops at the Free University in New York and were able to translate their expertise into Newsreel product. At the moment of Newsreel's formation in December 1967, it was decided that a film was needed to chronicle the October 1967 March on the Pentagon; Fishman was farthest along with a personal project along those lines. Newsreel #1 (1968), entitled No Game , was the result, despite the fact that the film bears only a passing resemblance to the "Newsreel style" familiar from the later works—scenes of conflict; lively, nonsynch music interspersed with multiple voice-over narrations from impassioned participants. There were concerted efforts made to disseminate the technical skills, but the difficulties were more deeply embedded than these well-intentioned attempts could hope to rectify. Women and minorities—after lifetimes of limited access to resources, possessing severely stunted self-images as producers of culture—were incapable of closing the gap overnight. Frustration and unspoken critiques festered beneath the surface of the organization.

And yet a necessary pragmatism reigned. In the words of Allan Siegel: "It was the kind of thing that if you came up with the money to do it [make a film], well then, you could do it. You made a film. I always used to stash myself away someplace and make things out of nothing. So I kept turning things out . . ."[16] Power and status were thus linked to the ability to produce despite the unequal distribution of the requisite tools for the task. In his discussion of Newsreel's collective process in the early days, Norm Fruchter recalls the inequities with some regret: