The "Great Sacrifice" of MANAS Recitation

Some three weeks after the conclusion of most of the annual Ramlila cycles in Banaras, there is another major public spectacle centered on a performance of the Ramcaritmanas . The venue of this program is the area known as Gyan Vapi, an L-shaped plaza located near the Vishvanath Temple, the city's most celebrated shrine.[43] The area takes its name from a sacred well located in one corner of the grounds, the water of which is drunk by pilgrims as a form of prasad from Shiva. The adjacent plaza is one of the few large public spaces remaining in the congested heart of Banaras; most of the surrounding area consists of a dense concentration of houses and narrow lanes, the latter usually crowded with pilgrims en route to or from the temple. At Gyan Vapi there is room to breathe, to relax in the shade of an ancient pipal tree (also sacred to Shiva and itself an object of veneration) growing near the well platform, and to recover from the pushing and shoving that, these days, is often an inescapable part of a visit to Baba Vishvanath. But the existence of this open space is significant in other respects as well. All Banarsis know that, although Vishvanath has been the patron deity of Kashi since time immemorial, his present temple is not especially old and is not in its original location. The shrine was destroyed in 1669 by order of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and a mosque built in its stead.[44] The present-day plaza is bordered on two sides by this mosque, which is elevated on a high plinth—actually the ruined foundation of the old temple, carved traces of which remain visible beneath the austere white walls of the mosque compound. The whole Gyan Vapi complex including plaza, mosque, well, and relocated temple, has come to represent, for Hindus, a controversial and disputed memorial to the perceived atrocities of Muslim rule, and for Banaras authorities, a source of potential communal trouble.[45] Thus, by virtue of its size, location, and emotional associations, the Gyan Vapi area is an appropriate site for the staging of large-scale Hindu religious performances. Among the best-

[43] The name is a popular romanization of the modern Hindi pronunciation of jnanvapi , "the well of knowledge."

[44] In fact, the shrine's location has changed several times and even the mosque site is not the oldest; see Eck, Banaras, City of Light, 120-35.

[45] Hindu claims to the area sparked rioting as. long ago as 1809 (ibid., 127); an anticipated Hindu attempt to "liberate" the mosque in the immediate post-Independence period was forestalled by the placing of troops there, but the issue was not laid to rest and emotional calls for the reclamation of the site continue to be raised, most recently in connection with the Hindu claim on a similar site in Ayodhya, where a mosque occupies the alleged birthplace of Ram.

known of these is one that begins each year on the seventh of the bright half of Karttik (October/November), when a mercantile organization known as the Marwari Seva Sangh (Marwari Charitable Society) sponsors its annual SriRamcaritmanas navahpath[*] mahayajna —a "great sacrifice of nine-day recitation" of the Manas .[46]

The commencement of the program is heralded by handbills and a large banner displayed on the main road between Godowliya and Chowk. They give the timings for daily recitation (mornings from 7:00 to 11:00 A.M. ) and for expositions on the epic by "renowned scholars" (evenings from 7:00 to 11:00 P.M. ). Meanwhile, workmen transform the dusty plaza into a festive enclosure by erecting a huge multicolored canopy (mandap[*] ), its bamboo posts festooned with chains of marigolds and auspicious asok leaves. At its southeastern corner they erect a dais, on which they arrange an elaborate tableau of life-size images of Ramayan characters. These are made of unfired clay sculpted over a framework of wood and straw, brightly painted and adorned with appropriate costumes, jewelry, and weapons. These temporary "likenesses" (pratima ), consecrated by a priest with the prescribed life-giving prayers, become as suitable for worship as more permanent images of stone or metal, even though they will only be worshiped for a fixed period and will then be desanctified and consigned to water. In Banaras such images are produced for a number of festivals, most notably for Durga Puja, which is lavishly celebrated by the city's Bengali population. Durga images are displayed in elaborate tableaux depicting the Goddess, adored by a host of subsidiary deities, in the act of slaying the buffalo-demon, Mahishasur. Since the Manas recitation festival at Gyan Vapi is of recent origin, it is likely that its use of a tableau reflects the influence of the Durga Puja observances.

The tableau offers a representation, immediately familiar from religious posters and calendars, of the culminating scene in the Ramayan story as recounted in the Manas , in which the victorious Ram is enthroned beneath a royal umbrella with Sita at his side, flanked by his three brothers, by Hanuman, and by his family guru, Vasishtha. Throughout the nine days of the festival, this tableau will be attended by a priest. It will receive the worship and offerings of devotees and will be the focus of arti ceremonies at regular intervals. At the conclusion of the program, the images will be taken in procession to Dashashvamedha Ghat for their "dismissal" (visarjan ) in the waters of the Ganga. To the

[46] The account given here is based on the festival I witnessed in November 1982.

Figure 6.

Copies of the epic rest on a harmonium during a break in a public

recitation program

right of the tableau is a raised seat spread with golden cloths; this is the vyaspith[*] , or "seat" of the Ramayan expert who will serve as master reciter and also of the invited scholars who will discourse during evening sessions. Before it is a wooden stand likewise covered with glittering cloths, upon which rests an enormous copy of the Manas . Like the adjacent images, it too is an object of worship; devotees bow to it as they file past and place offerings of flowers and money on its pages.

Near the entrance to the plaza is a small tent housing the equipment that controls the sound and lighting system. Festive illumination and powerful amplification are indispensable parts of religious events in India these days, and the arrangements for the Gyan Vapi program are typically elaborate. The entire mandap[*] is wired for light and sound, with tube lights and loudspeakers mounted on every post, a flickering, multicolored marquee around the images, and hanging microphones to pick up the chanters' voices. The broadcast range of the festival does not end at the boundaries of the plaza, however; a tangle of wires emerging from the sound tent activates a network of some three hundred loudspeakers installed throughout several square miles of surrounding neighborhoods in central Banaras. As I cycled to the program each morning from the southern part of the city, I encountered the first loudspeakers at the

Godowliya crossing, more than a kilometer from Gyan Vapi. From that point on I could follow what was going on in the mandap[*] .

Such large-scale broadcasting of a religious event struck me as rather unpleasantly intrusive, particularly as I supposed the installation of loudspeakers was imposed on the community by the wealthy organizers of the festival. My conversations with shopkeepers and residents in adjoining neighborhoods altered this impression, however, for no one complained about the loudspeakers and in fact the majority of the comments that I heard were positive. "You don't have to leave your shop to go to the program," remarked one merchant, "you can just listen whenever you feel like it." Moreover, I learned that most of the speakers were set up at the request and expense of groups of residents themselves. According to a bank officer who lived near the Vishvanath temple, the cost of installing each speaker (about seventy-five rupees) was met by taking up a collection (canda ) among area residents. "Then it is going from 5:30 in the morning till 11:00 at night," he said with apparent satisfaction, "and you can just listen whenever you feel inclined to give your attention."

Although the two daily sessions that constitute the Gyan Vapi festival—morning recitation and evening exposition—are thematically linked and form a cohesive event in the minds of participants, they are structurally quite distinct. The kinds of performance that occur in the two sessions are discussed separately. Here I confine myself to the morning sessions and make only passing reference to the exposition programs, as these are treated in detail in Chapter 4.

The Reciters

The daily program begins with early-morning arti to "awaken" the images; this is the responsibility of the attending priest and is of little public interest. Preparations for the program really get under way between 6:30 and 7:00 A.M. , when the hired reciters begin assembling in the enclosure. During this time, a group of Muslim musicians dressed in brocaded coats and caps take their seats on a small dais near the entrance and begin playing a morning raga. The sound of shehnai and tabla drifting over the misty ghats and through the bazaars of the awakening city announces in a most elegant fashion the approaching start of the program. A goldsmith from the nearby jewelers' bazaar pointed out to me with satisfaction the presence of the musicians and the absence of blaring Hindi film music, so common at public events; "You see, here they want to create a religious and cultural atmosphere."

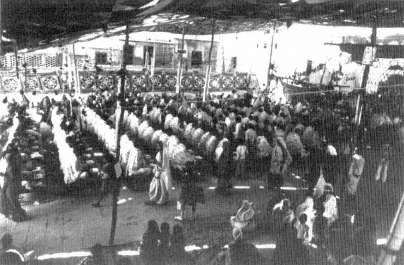

Figure 7.

One hundred eight uniformed Brahmans chant the Manas at the

Gyan Vapi festival

Just as the musical overture betokens the good taste and largesse of the organizers, the number of reciters confirms the grandeur of conception of this "great sacrifice." There are to be, as the banner on the main street announces, 108 Brahmans chanting the Manas , and the morning activities of workmen in the plaza include the setting up of nine rows of low platforms, on each of which, as at a banquet table, places are set for twelve reciters—with woven mats, wooden bookstands bearing uniform Gita Press editions, and copper vessels and spoons for ritual oblations. On the first day, reciters are also presented with yellow dhotis and Ram-nam shawls; these are to be their costume throughout the program. The number 108 is auspicious, and so determined are the organizers to maintain it at all times that they station two "spare" reciters on a side platform, ready to assume the place of any who may need to attend to nature's call.

Participants are selected six days before the program in an examination conducted by the chief reciter. The criteria for selection are simply that one be able to read and be sufficiently conversant with the Manas to be able to chant it at varying speeds. However, admission to the examination is restricted to persons possessing an official entry form, and there is brisk competition to obtain these—one reciter told me that they are sometimes sold for as much as one hundred rupees. Although

the Gyan Vapi program is the oldest and best known of the growing number of Manas- recitation festivals held in Banaras each year, it is not for prestige alone that Brahmans vie to participate in it. Nor is it for the official payment (daksina[*] ) given by the organizers—in 1982 a token fifteen rupees plus the tangible gratuities (dhoti, shawl, etc.) already mentioned. The great material benefit of participation in this program comes in the form of gifts in cash and kind, received from the public in the course of the recitation. The giving of gifts to Brahmans has always been regarded (especially by the Brahman authors of legal texts) as a meritorious and purifying activity, and legends celebrate the generous gifts that ancient kings gave their ritual specialists on the completion of Vedic sacrifices. In the same way, the patrons of this "sacrifice," the householders and widows of the Marwari business community, expect to gain merit by conferring gifts on the reciters, visible and publicized merit, one may add, since the giving is done in front of spectators and is announced over the far-flung audio system.

This gift giving can occur at any time, and some of the more humble sort takes place every day; elderly ladies, heads respectfully covered, thread their way down the long lines of chanting Brahmans, placing a banana, sweetmeat, or ten-paise coin in front of each, and then "taking the dust" of his feet on their foreheads. But the most lavish giving occurs on days when the recitation is dominated by a joyous event: Ram's birth (Day Two), marriage to Sita (Day Three), victory over Ravan (Day Eight), and enthronement (Day Nine). On these days the reciters come equipped with cloth bags to carry home the "loot" they are sure to receive.[47] This includes, by the end of the program, as much as four hundred rupees cash, as well as such practical items as wool blankets, cotton scarves, and stainless-steel bowls—all donated by local merchants. Each presentation is announced by the chief reciter, who interrupts the chanting at the end of a stanza to read, from a slip of paper handed to him by a member of the organizing committee, some such message as "Shrimati Nirmala Devi, in memory of her heaven-gone husband, Seth Raghunandan Lal-ji, presents to the gods-on-earth on the auspicious occasion of the Lord's royal consecration a daksina[*] of two rupees each." The announcement is greeted by a loud cheer from the assembled "gods," who then resume their recitation. Gift giving reaches such a pitch during the description of Ramraj on the final day that the

[47] The Brahmans themselves jokingly use the word lut[*] (spoils), which has come into English from Hindi.

reading is interrupted after virtually every stanza by an announcement of this sort.

The Brahmans are honored in other ways as well. On their arrival each morning, their feet are ceremoniously washed by a member of the organizing committee, an elderly merchant known for his exceptional piety. And each morning's session is broken by a forty-five-minute rest period during which reciters are served a substantial snack of tea, savories, and fruit. A different family undertakes the provision of refreshments each day, and the name of the host is duly announced before the break.

Beginning Each Day's Program

The reciters come from all over the city and from as far away as Ramnagar—roughly ten kilometers distant, on the other side of the Ganga. All are supposed to be present and ready to begin by 7:00, but the program rarely starts on time -and many participants straggle in between 7:30 and 8:00. It is autumn and there is a misty chill in the air, but here and there shafts of sunlight stab through openings in the mandap[*] . While the musicians play and the washing of feet goes on near the well platform, reciters stand around chatting or slowly change into their festive uniforms. The unhurried atmosphere changes to one of feverish activity, however, at the arrival of the chief reciter, the sternly venerable Shiva Narayan. A dignified man of perhaps seventy-five years, whose association with the festival dates back more than a quarter of a century, Shiva Narayan slowly enters the enclosure, pausing at intervals to receive the homage of the many who come forward to touch his feet. He then prays silently before the diorama while late arrivals scurry to their places to avoid incurring their leader's displeasure. For in this most unpunctual of cities, Shiva Narayan is known to be a stickler for punctuality, at least where Manas recitation is concerned.

This trait is forcefully demonstrated on the third morning of the program, when the leader takes his seat on the podium somewhat earlier than usual, to discern a less-than-full complement of reciters filling the neat rows in front of him. Waiting extras are delegated to fill two of the empty places and the preliminary rituals are begun. Meanwhile, several of the offending Brahmans straggle in and attempt to make their way as unobtrusively as possible to their assigned places. None escapes the leader's stern gaze, however, and the ritual is periodically interrupted by a humiliating exchange such as the following (all, of course, broadcast to the city at large):

Figure 8.

Shiva Narayan, the chief reciter at Gyan Vapi in 1982 (note the

places set for two "spare" reciters to the right of the dais)

SHIVA NARAYAN : | YOU there, fifth row, middle. Come up here! (embarrassed silence as the Brahman reluctantly shuffles forward) All right now, tell us, why are you late? (mumbling and shuffling of feet) Come on, speak up! What's your excuse? |

BRAHMAN | (weakly): I was doing my puja-path[*] . . . . |

SHIVA NARYAN (loudly and with obvious sarcasm): | Oh you were doing your puja-path[*] ! And what do you think we're doing here? (pause to let laughter subside, then sternly) You were supposed to be here at 7:00, and you have kept us all waiting. (pause to let it sink in, then, peremptorily) Go, sit! |

This little exercise has the desired effect, and all reciters are in their places well before Shiva Narayan's arrival on subsequent mornings.

The daily recitation is preceded by a complicated ritual of self-dedication and purification, performed in unison according to instructions printed in Gita Press editions of the Manas .[48] Following invocations of Tulsidas, Valmiki, Shiva, and the principal characters in the epic, each Brahman pours a few drops of Ganga water on his right palm, utters a

[48] The interpretation of the ritual given here is based on an interview with Shivdhar Pandey (February 1984), a priest in the service of the maharaja of Banaras, who had taken part in the Gyan Vapi program for seventeen years.

Figure 9.

Reciters at Gyan Vapi

prayer in praise of Manas recitation, and lets the water fall to the ground—thus affirming his "resolve" (sankalp[*] ) to complete the parayan[*] in the prescribed fashion. The next stage of the ritual purifies the body by the sprinkling of drops of water over the head, the taking of a ritual breath (pranyam[*] ), and the making of various ritual gestures (mudra ), such as passing the right hand over the head and then clapping loudly ("to remove all impediments"). A whole sequence follows of "impositions" (nyas ) of divine powers on various limbs of the reciter's body, each accompanied by an appropriate mudra and the recitation of a verse from the Manas , which here serves as the mantra to effect the desired "imposition."[49] The final phase of the ritual is meditation on the Lord (dhyan ), accompanied by the recitation of a hymn to Ram sung by Narad in Uttar kand[*] (7.51.1-9). The leader then commences the day's recitation.

Although the general purpose of these preliminary rites, which occupy about half an hour, seems clear enough—the purification and

[49] Thus, in part of the ritual entitled "imposition on the heart, etc.," the reciter chants the verse "The praises of Ram effect the welfare of the universe / and bestow liberation, wealth, virtue, and beatitude" (1.32.2). This is followed by the Sanskrit phrase hrdayaya[*]namah[*] (salutation to the heart) and the placing of the right hand, tips of fingers joined, over the heart. The whole mudra and nyas sequence closely follows the liturgy prescribed in the Agastya samhita[*] , a c. twelfth-century Ramaite text, which itself appears to reflect older pancaratra practices. See Bakker, Ayodhya , 92-93.

sacralization of the reciter—what is more interesting is the contrived complexity of the Sanskritized ritual. The text consists of a mélange of Manas verses framed by Sanskrit formulas, but the fact that even the accompanying instructions are given in Sanskrit is a clear indication that this procedure is not meant for everyone. When I asked a non-Brahman acquaintance who frequently engaged in parayan[*] recitation whether she carried out these preliminaries, she replied, "No, the words are too difficult for me, and I am afraid of mispronouncing them, so I just say the Hanumancalisa ." It is well known that the mispronunciation of a mantra can have serious consequences,[50] and one can hardly escape the conclusion that the intent of the elaborate procedure described above is to enhance the role of the ritual specialist.

The chanting itself is to the melodious Tulsivani[*] with the usual refrain (mangalabhavana amangala[*]hari , etc.) and is performed antiphonally, with each half-line first being sung by the leader and then repeated by the assembly. The tempo is changed frequently according to a slow-to-fast cycle, each change being signaled by the rate at which the refrain is sung before the start of a stanza. The slowest tempo is solemn and majestic, and listeners can easily follow the recitation. After a stanza or two the pace is gradually increased until the reciters are literally racing through the text, and whole lines seem little more than a blur of sound. Then abruptly, the leader reverts to the slowest speed and the cycle begins again. The structural pattern of antiphonal singing and repeated slow-to-fast cycles is shared with other genres of Indian musical performance—for example, seasonal folksinging, devotional kirtan , and the chanting of the Manas in Ramlila .[51] This progression from meditative opening to frenzied climax, lapsing back again into quiescence, is characteristic of much Indian classical music as well—and not of Indian music only, of course (cf. Ravel's "Bolero"), although the pattern may predominate more on the Subcontinent than elsewhere. A sexual metaphor is one obvious level of interpretation, but the pattern may resonate

[50] A classic example is the myth of Tvashtri's yajña undertaken to produce a hero capable of killing Indra. At the crucial moment, Tvashtri pours an oblation into the fire while declaring his wish, and Vritra is born. But because of a mispronunciation, the one who should have been "the slayer of Indra" becomes "[one] having Indra as his slayer"; see Eggeling, trans., The Satapatha Brahmana[*] 1:166 (1.6.3.10). I am grateful to Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty for assistance in locating this reference.

[51] Cf. Henry's observation: "Like phagua , harikirtan consists of a series of cycles, each beginning at a slow tempo and moderate volume and accelerating to the verge of frenzy, when . . . the climax is abruptly terminated and the singing and playing resumed at a slower tempo and lower volume, to begin the cycle anew." "The Meanings of Music," 155.

with other equally primary cosmic cycles. At Gyan Vapi the aural effect of the unison chanting of 108 voices is most impressive, both within and beyond the enclosure; the words of Tulsidas literally resound through the city.

Equally impressive is the spectacle of long rows of identically dressed chanters, all facing the gaudily decorated dais. While they recite, other activites go on around them. A steady stream of worshipers passes through the enclosure, many of them bathers returning from the ghats. Most proceed directly to the front for the darsan of the divine tableau and to offer a coin or flower and receive a spoonful of sanctified water from the officiating priest. Some then proceed to adjacent seating areas where they listen to the recitation or pull out their own copies of the Manas and join in. Others engage in a meritorious circumambulation of the reciters (parikrama ), using a wide track left for this purpose; throughout the nine days it is in heavy use by tireless devotees intent on benefiting from the merit generated within its holy quadrangle. By mid-morning on most days, the walk is thronged with a shuffling mass of humanity: bent old ladies clutching brass vessels of Ganga water; businessmen dressed for work; college students with bookbags, apparently en route to school; packs of children racing playfully around the periphery, convinced (as Banaras children always seem to be) that it is all a wonderful game—a spiritual Caucus Race. No one seems to do just one rotation; everyone goes around repeatedly. I guess that many do some fixed, auspicious number (1087), but always lose count trying to keep score. The uniforms of the Brahmans and the bright-colored saris and shawls of the devotees create a striking effect: an ocher grid framed by a rotating wheel of colors.

Other Perormance Elements

Each day's installment requires about five hours to complete, but it is interrupted periodically to introduce elements of participatory drama that help bring the story to life for the assembled devotees. On the occasions of Ram's birth, marriage, and enthronement, when huge crowds pack the mandap[*] , Shiva Narayan halts the reading just before the crucial passage to address the people briefly regarding its significance and give instructions for their participation. Flowers are distributed to the spectators and the recitation resumes slowly while an arti of the images is performed under a rain of blossoms, cherry bombs explode outside the enclosure, and the plaza echoes with thunderous cries of

"Bolo Raja Ramcandra ki jay!" Appropriate rituals are performed: the images of Ram and Sita are "married" by the priest's tying a silk shawl between them; vermilion is placed on the part of Sita's hair, and so on. There are moments when the reciters too assume a role in the story. During the enthronement scene when they come to the half-line "The Brahmans then chanted Vedic mantras" (7.12.4), they stop reading and, true to their training, intone a Vedic chant, while the priest on the dais applies the royal tilak to the forehead of the Ram image.

The killing of Ravan (Day Eight) occasions a unique performance. As the moment of victory approaches, the circumambulatory track is cleared, and excitement grows as spectators crane forward to see what is going to happen. While the Brahmans slowly chant the account of the final combat, a strange figure enters the enclosure and begins to circumambulate them. It is a hooded man dressed in a black robe, bearing on his head a large clay pot garlanded with marigolds. Seeing him, I thought at once of a death figure from a medieval mystery play; and of course, he is Death—Ravan's doom, now approaching in a fatal orbit. Again and again he circles, until the reciters describe Ram's release of thirty-one deadly arrows.

One arrow dried up the nectar pool in his navel,

the others furiously severed his arms and heads.

Carrying them away, the arrows flew on;

the headless, armless trunk danced on the earth.

6.103.1,2

Suddenly breaking its orbit, the black-clad figure flees the arena, mounts the ruined plinth of the old temple, and shatters his pot against the stones, while fireworks explode and the crowd cheers Ram's victory.

Other Nine-Day Programs

One indication of the success of the Gyan Vapi festival, in its twenty-seventh year in 1982, was the number of imitations it inspired. During my stay in Banaras I observed ten such annual programs, and I was aware of the existence of others. I witnessed similar programs in Delhi and Ayodhya and collected handbills for others from places like Kanpur and Bhopal. The practice is apparently on the rise, with new programs being added each year. There is considerable variety in the sponsoring institutions: a Sanskrit college, a school for the blind, a Devi temple, a businessmen's association, and—in one case—a hotel, as well as many

Hanuman temples. All these programs postdate the one at Gyan Vapi and most are of recent origin. The Sankat Mochan festival, said to be the city's second oldest, was in its seventeenth year in 1982, while the Vighna Haran Hanuman Temple's program was in its tenth, the Kamaksha Devi Temple's was in its fifth, and that of the Lakshmi-Narayan Lodge (a hotel near the Banaras railway station) was in its third year. Although the sponsors of such programs are apt to emphasize Manaspracar (promulgation of the Manas ) as their primary motive, it is clear that a further aim is often to attract patrons and publicity.

A case in point is the Kamaksha Devi program, sponsored by a small temple near the Central Hindu School on Annie Besant Road. A nearby resident told me that only twelve years earlier the locality had been an unfrequented section of the city's outskirts and the temple itself in ruins. A sadhu, Swami Dhiraj Giri, settled there to pursue his sadhana and his reputation for holiness, combined with the increasing southwestward expansion of the urban area, gradually led to the temple's acquiring a steady clientele, appointing a full-time priest, and undertaking repairs and embellishments. By 1982 Kamaksha Devi presented the appearance of an up-and-coming religious complex in a rapidly urbanizing area.[52] Yet because the temple was located on a back lane, it did not attract as many passersby as might be desired. The Manas recitation program, for which a large banner and loudspeakers were erected along the main road, seemed to be an additional attempt by the priest and his patrons to help put this temple on the religious map of Banaras.

The basic pattern of all nine-day programs is the same: Manas recitation in the mornings by a fixed and auspicious number of Brahmans and commentary on the text in the evenings by invited speakers. The number of reciters is a prime indication of the largesse of the sponsors: the Vighna Haran Hanuman program employs fifty-two, whereas tiny Vankati Hanuman features thirteen, and Kamaksha Devi, eleven. At least one of the programs—that of the Sankat Mochan Temple—is comparable in scale to that of Gyan Vapi. Here too the sponsorship of the program may be viewed as one element in the rise to prominence of a temple that—though now among the city's most venerated—even a few decades ago consisted of only a small shrine surrounded by mud walls, located in a "wild" (jangli ) area that many Banarsis considered unsafe to visit.

[52] Ironically, Swami Dhiraj Giri, who left to found an ashram in Uttarkashi in the Himalayas, was said to have returned for a visit and observed that the changes had ruined the atmosphere of the place, rendering it unsuitable for sadhana .

Figure 10.

In a temple diorama, Hanuman appears to fly through a firmament

of colored lights

Like the program at Gyan Vapi, many of the newer ones incorporate visual or audience-participatory elements into the bare recitation. One of the most remarkable efforts is by the Vighna Haran (Remover of Obstacles) Hanuman Temple, located in a small lane near the Mazda Cinema in the area known as Laksa. This temple has also come to prominence only recently, under the leadership of Mohini Sharan, a local perfume merchant who became the disciple and spiritual successor of a revered Ramanandi sadhu and now commands a wide following in the city. The temple itself is a recent structure, but it enshrines a huge stone image of Hanuman that, like many others in Banaras, is popularly held to date from Tulsidas's time. Below its conventional spire, the boxlike temple presents the appearance of an outdoor stage, with its open front wall exposing a deep-set rectangular interior, at the rear of which stands the Hanuman image. A prosceniumlike platform extends in front of the temple, which faces an empty lot. For the Manas recitation program, the theaterlike features of the site are fully utilized: the empty lot is carpeted and covered by a mandap[*] ; the front platform serves as a dais, with the vyas seat placed on one side of it; and the brilliantly illuminated interior of the temple forms a natural backdrop and visual focus. To this already attractive setup, Mohini Sharan has added a further theatrical touch,

which has brought particular renown to his program: the daily mounting of an elaborate tableau (a jhanki , or "glimpse") of a scene from the Manas .

The themes of the nine tableaux represent high points in the recitation. Day One's jhanki of the marriage of Shiva and Parvati, for example, depicts the wedding procession of Shiva and his grotesque attendants moving across a heavenly landscape of cotton-wool clouds, while off to one side a bejeweled Parvati, holding the marriage garland, waits with her parents before an illuminated cardboard palace. The shimmering lights and doll-like figures remind me of a Christmas window in an American department store, and the viewing area in front of the temple is often thronged with smaller darsan seekers, gazing at the scene in wide-eyed delight—and, of course, learning the Ramayan at the same time.

Each day's tableau is on display from 7:00 A.M. till the closing nighttime arti at about 10:30 P.M. ; a curtain is then drawn across the front of the temple while the work of changing the scene goes on throughout the night. Subsequent tableaux are no less spectacular than the first; for the phulvari scene on Day Two, the interior of the temple is transformed into a garden with masses of potted flowers and shrubs, a canopy of leaves and tiny electric bulbs overhead, and geometric designs of grass clippings and crushed stones on the floor. But the undoubted pièce de résistance in the view of festival goers is Day Four's tableau of "the crossing of the Ganga": a low glass wall is cemented into place at the front of the temple and the whole building is flooded with a foot of water, on which lotuses float and in which some forty live fish swim, while a wooden rowboat (inscribed with the name of a local paint store) bears the figures of Ram, Sita, Lakshman, and their devoted ferryman.

In other respects, the program follows the pattern of Gyan Vapi, although on a more modest scale. The sponsoring patron adds another kind of performance on the afternoon of the final day, taking the program into the heart of the city with a nagar sankirtan[*] procession[53] that includes two elephants, the fifty-two uniformed Brahmans, and boys on caparisoned horses dressed in the conventional manner of Ramlila players representing Ram, his brothers, and Sita.[54] When the procession returns to the temple in late afternoon, an elaborate wedding ceremony of the divine couple is staged.

[53] "Chanting the Lord's name through the town"—a practice popularized by the fifteenth-century Bengali mystic, Chaitanya.

[54] The term svarup (literally, "form" or "likeness") is applied to Brahman boys who impersonate and are believed to incarnate deities.

Figure 11.

For the tableau of Ram's crossing of the Ganges, the temple's inte-

rior is flooded

Recitation as "Sacrifice"

The evidence of the various nine-day programs illustrates how readily the comparatively new phenomenon of festive public recitation of the Manas lends itself to embellishment with a variety of popular religious and folk-performance forms: circumambulation, almsgiving, tableaux, Katha and kirtan programs, processions, and lila -like dramatizations. Yet sponsors characteristically style such programs yajñas, and in structure they do indeed resemble the large-scale Vedic sacrifices revived in recent years under the sponsorship of religiocultural organizations.[55] To the contemporary Hindu public, these ceremonies have a certain novelty value, but since Vedic ritual in fact plays little part in religious life, some pretext must usually be found to integrate them into the popular ritual cycle. Thus, in Jaipur in 1980 a Hindu organization conceived the idea of celebrating Mahashivaratri (the Great Night of Shiva—a pan-North Indian festival) with a fourteen-day Rudra mahayajna (a great sacrifice to Rudra, the Vedic precursor of Shiva) held in a specially constructed pavilion (yajnasala ) in one of the public courtyards of the City Palace, where eleven fire altars were continuously fed by priests chanting verses

[55] For an account of the 1976 Agnicayana in Kerala, see Staal, Agni: The Vedic Ritual of the Fire Altar.

honoring Rudra. The public was encouraged to attend, but since most people evidently had little idea of the significance of the ceremony, signboards were erected to explain what was going on, while loudspeakers urged viewers to circumambulate the enclosure and to make cash donations to defray the cost of the many expensive ingredients being offered into the fires.[56]

Although such events continue to be held periodically, they are more like cultural museum pieces—restorations of behavior, to borrow a phrase from performance theorist Richard Schechner[57] —than reflections of living traditions. Interestingly enough, the inspiration for the first Manas-mahayajna is said to have come from Swami Karpatri, a Dasnami ascetic leader and vociferous advocate of Brahmanical orthodoxy, who was himself involved in the promotion of Vedic sacrifices in Banaras during the 1940s.[58] What Karpatri and his mercantile patrons hit upon at Gyan Vapi—undoubtedly influenced by the tradition of public recitation of the Puranas—is a "sacrificial" ritual that borrows some of the time-honored forms of older rites but reorients them around a popular text with which people can identify. The ritual specialists are still present in their serried rows, properly purified by a concocted Sanskritic liturgy, but the place of the fire altar is now occupied by the Manas itself and the mantras filling the air are its verses, the Very recitation of which is deemed a merit-releasing act. The sacrificial format, the auspiciousness of the chanted word, the giving of gifts to pious Brahmans: these age-old traditions are publicly reaffirmed not through the medium of the Sanskrit Veda but through a vernacular text that has eclipsed it in popularity and perhaps even equaled it in prestige.[59] Clearly the whole symbolic structure and validity of this "great sacrifice" rests on public acceptance of the sanctity and authority of the Manas .

[56] A similar yajña with a Vaishnava orientation was organized by the mahant of a temple in Ayodhya to coincide with the Vivah Panchami observances (celebrating the anniversary of Ram and Sita's wedding) in December 1982. The event was held near the banks of the Sarayu in the usual thatched yajnasala; in the midst of the tumultuous wedding festivities in the city, it attracted little notice.

[57] Schechner, Performative Circumstances from the Avant Garde to Ramlila, 164-237. Schechner does not use this term in a necessarily pejorative sense, although he is critical of what he sees as media manipulation in the staging of the Agnicayana rite.

[58] Karpatri's Ramayan-related activities are further discussed in Chapter 6, The Politics of Ramraj .

[59] Such an "eclipse" is characteristically perceived as an additive act rather than a usurpation; the Veda remains, though, as in the Tamil Vaishnava tradition its chanters may now be placed behind the Lord's chariot while the singers of Nammalvar's "Tamil Veda" lead the procession; Ramanujan, Hymns for the Drowning, 126-34.