Differences Among Malignancies

For individuals and professionals concerned with promoting survival, the variations among individual forms of malignant disease are crucial. In general, it is virtually meaningless to ask whether cancer is "curable" or how long a cancer patient may be expected to live. The answer to either question depends largely on three factors: the anatomical site at which the cancer originates, the stage at which it is diagnosed, and the histology , or specific type of cell of which it is composed.

Figures 1 through 3 summarize the "cancer problem" as it played out in the United States in 1990. In that year, the American Cancer Society estimated that 1,040,000 Americans would be diagnosed with cancer, and 510,000 would die of the disease.[2]

American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts and Figures—1990 (Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 1990).

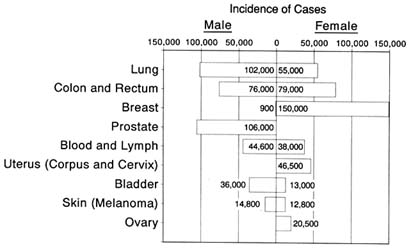

These figures do not mean that nearly half of those who were diagnosed in 1990 would die in that year. Most of these deaths would occur among people diagnosed in earlier years.Figure 1 indicates the most frequent cancers that experts expected to occur in the United States in 1990. The figure provides information on the "incidence" of each form of cancer for 1990; that is, the number of new cases diagnosed in that year. It presents the number of new cases of cancer at each "primary site," or the location in the body where it first appeared. The figure provides separate totals for men and women. It includes data on only one form of skin cancer, malignant melanoma. While other forms of skin cancer were expected to number 600,000 in 1990, these spread very slowly if at all and seldom cause death.

The nine separate forms of cancer represented in Figure 1 encompass almost 75 percent of the new malignancies expected in the United States in 1990. Not represented in the figure are many less frequent but hardly rare forms of cancer, such as pancreatic (29,000 cases expected in 1990), stomach (23,000 cases), and liver (15,000 cases). It is important to remember that the majority of Americans with cancer in 1990 had contracted the disease in previous years. The total "prevalence" of cancer in 1990—that is, the number of individuals with cancer (including those permanently cured)—was around 6,000,000.[3]

Farber, "Cancer Development."

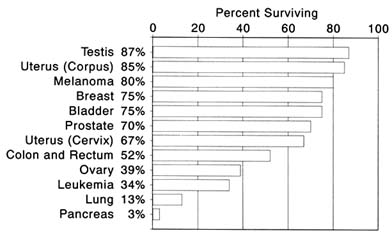

An overview of survival rates for the most common forms of cancer reveals great variability by site. Figure 2 summarizes the survivability of

Fig. 1. Cancers diagnosed, by sex and most frequent site, 1990.

Source: Cancer Facts and Figures 1990. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 1990 .

Fig. 2. Five-year survival rates by most frequent cancer site, 1990.

Source: Cancer Facts and Figures 1990. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 1990 .

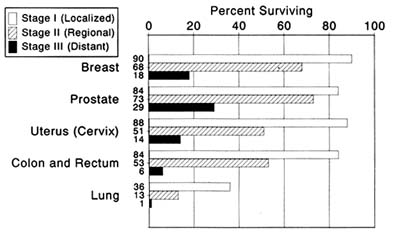

Fig. 3. Five-year survival rates by cancer stage: differences by site.

Source: Cancer Facts and Figures 1990. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 1990 .

twelve cancers in the United States based on records compiled between 1974 and 1985. The primary site of the cancer made an overwhelming difference in chance for survival. Figure 2 indicates the percentage of individuals who survived five years or more after diagnosis, a widely used benchmark to signify successful treatment. For all stages combined, highs of 87 and 85 percent survived five years or more for cancers of the testis and uterine corpus; lows of 13 and 3 percent survived a similar length of time for cancers of the lung and pancreas.

Stage makes a statistical difference in survival of most if not all the forms of cancer. Figure 3 lists five-year survival rates by stage for the most frequently diagnosed cancers in 1990. For all diseases represented in Figure 3, persons diagnosed in Stage I had a considerably greater likelihood of surviving five years than those diagnosed in Stage III. Among patients with lung cancer, for example, those diagnosed in Stage I had a thirty-five times greater chance of surviving five years than those diagnosed in Stage III.

But early-stage diagnosis does not always increase survival chances in a meaningful way. For some cancers, diagnosis is almost never made in the early stage. Lung cancer is a telling example. In one study, which omitted the most aggressive form of the disease and meticulously confirmed degree of dissemination, fewer than 18 percent of the cases were diagnosed in Stage I.[4]

N. Martini and E. J. Beattie, "Results of Surgical Treatment in Stage I Lung Cancer," Journal of Cardiovascular Surgery 74 (1977): 499-505.

In other cancers, people may have a relativeadvantage from early-stage diagnosis but still stand only a small chance of long-term survival. Even at Stage I, for example, only 6 percent of patients with pancreatic cancer survive five years.[5]

American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts and Figures.

Figure 3 actually represents the variability of cancer survival in a highly simplified fashion. A major study by the National Cancer Institute, based on over 500,000 Americans diagnosed with cancer between 1973 and 1977, identified 304 different primary sites.[6]

J. L. Young et al., Cancer Incidence and Mortality in the United States, 1973-1977, NCI Monograph no. 57 (Bethesda, Md.: National Cancer Institute, 1981).

Physicians and scientists draw important distinctions within the individual cancer sites listed in Figure 1. Thus, colon cancer may occur in a particular segment of the large intestine, so that the patient may have a cancer of the sigmoid colon, descending colon, transverse colon, ascending colon, or cecum. These four, moreover, include only the most common forms of colon cancer.In addition, major differences occur among cancers according to the microscopic characteristics of the cancer cells themselves, or "histology." The National Cancer Institute report identified up to twenty specific histological types associated with some anatomical sites. In lung cancer, for instance, the tumors may be designated as squamous cell carcinomas, small or oat cell carcinomas, or adenocarcinomas, to name the most frequently diagnosed; there are also rarer, exotically named tumors such as giant or spindle cell carcinomas, clear cell adenocarcinomas, or signet ring cell carcinomas.

Although histology is a characteristic of cancer less familiar to most people than site or stage, it is often an important clue to prognosis. Summarizing studies of patients who had received surgery for lung cancer before 1982, one authority reported strikingly different five-year survival rates for different histological types: bronchoalveolar carcinoma, 51 percent; squamous cell carcinoma, 33 percent; adenocarcinoma, 26 percent; small cell carcinoma, 1 percent.[7]

Z. Petrovice and R. A. Figlin, "Lung Cancer," in Cancer Treatment, 2nd ed., ed. C. M. Haskell (Philadelphia: Saunders, 1985), pp. 180-211.

All forms of lung cancer are serious. When all stages and histologies are analyzed together, only 13 percent of those diagnosed with this disease are found to live five years or more. Patients with some forms of lung cancer, however, have significant chances for survival if diagnosed and treated early. In other forms—most notably, lung cancer of the small cell type—stage apparently makes little difference. This histological type of lung cancer has been characterized as "explosively" metastatic, forming multiple lesions in the lung and other organs before it produces symptoms or becomes detectable.Other features of individual cells may distinguish cancers of the same anatomical site. Grade, for example, refers to the differentiation among cells as they appear under a microscope. "Well-differentiated" cells bear

close resemblance to normal ones; they are relatively uniform in size and have clearly defined features, such as nuclei and boundaries. "Poorly differentiated" cells vary significantly in size and shape and have less well-defined features. Poor differentiation may, as in cancer of the prostate, indicate a poorer chance of survival. In some cancers, cells become less and less well differentiated as the disease develops. Cells in apparently similar cancers may differ in their ability to bind with certain hormones. These differences may, in turn, affect a patient's treatment options and life expectancy.

Possible combinations of site and histology run into the thousands. In some ways, each site-histology combination represents a different disease. Some cancers remain localized, while others move aggressively to invade nearby organs or metastasize to distant sites. Some forms of cancer spread beyond their points of origin in regular, predictable ways, spawning metastatic lesions in the same organs in nearly every case; others are more nearly random in the speed and pattern by which they spread. Each site-histology combination presents unique problems for the physician in planning treatment.

Site, stage, and histology answer a large part of the question "Who survives cancer?" People who develop cancers with especially bad combinations of these disease features have virtually no chance of living more than a few years; those with more favorable forms of the disease may have excellent chances for long-term survival. At least in the late twentieth century, these basic biological features acted as boundaries to the benefits of medicine.