PART TWO—

DISTANT RELATIVES:

CROSS-CULTURAL REMAKES

Nine—

The French Remark:

Breathless and Cinematic Citationality

David Wills

I am not, it seems, in the cinema. Not even in the video. This all comes at a complicated series of removes. At some point I could have said, "I am in the cinema," and left the ambiguity at play between the theater room and the film on the screen. The metonymy works for theater and cinema, but not for video. Yet this is the position I am in, watching a film on video years after its commercial release. In fact, since I was only six in 1959, I was never in the cinema of A bout de souffle; it has always come to me by means of a series of detours. But the metonymic ambiguity of being in the cinema allows for that, and a more general detour mechanism allows even for the current state of affairs whereby I am watching the American remake of A bout de souffle (Breathless , 1983) before I take another look at the original. The chronological wires are crossed: the first thing I watch is a remake.

So it seems I am really not in the cinema. Not even in the video. I am here uttering these things to you the reader, having been there, various versions of "there," writing them. Everything I utter has a complicated play of quotation marks about it, not just because this reading is something of a recital of what I have previously written, but because in a more irredeemable fashion everything I write refers back to a "there"—a film, an experience of watching it, over and over—it refers back to an act of detaching, operations of excision and grafting, functions of de- and recontextualization. That which is a necessary fact of any reading, what we can call the "quotation" or "citation" effect, becomes even more explicitly the case once we come to talk about remakes.

But perhaps I am in the cinema. Perhaps even in the film. Perhaps, even as I write this in front of a screen—a cinema screen, a TV-video screen, a word processor monitor screen, a page—and even as this gets repeated like some sort of screen in front of its submobile and visually stimulated, if not

scopophilic, reader, I am more than ever in the cinema. I say that because as viewer and reader myself I am automatically and inevitably involved in the grafting or (de) recontextualization process just referred to. But I by no means initiate such a process. The film was never an intact and coherent whole offered up for my consumption. It was always, one might say, in the process of writing itself. Quoting, one might say "always already." Always writing and quoting itself. Remarking and remaking itself. Thus what is being commonly and communally referred to here as the remake, the possibility that exists for a film to be repeated in a different form, should rather be read as the necessary structure of iterability that exists for and within every film. That, at least, is my hypothesis, drawn of course from Derrida in work such as "Signature Event Context" (1982) and "The Law of Genre" (1980). First, "every sign . . . can break with every given context, and engender infinitely new contexts, in an absolutely nonsaturable fashion"; but second, as a corollary to that "the possibility of citational grafting . . . belongs to the structure of every mark" and "constitutes every mark as writing" (1982, 320), that is to say, as iterable mark, as remark, as remake. And the cinematic mark is no exception. The slightest mark is being remarked or remade even as it is being uttered or written, to the extent that it cannot make itself as full presence, as intact and coherent entity. It constitutes itself as reconstitutable, at least it must do so in order to function, that is to say, in order to make sense.

Thus what this book refers to as the remake—the essays demonstrate that as soon as we investigate the category its edges begin to blur—is but a particular case of what exists within the structure of every film. The remake has its own codes and practices and by means of them it is able to distinguish itself from another category of films: those not remade in the same set of varied institutional forms. But what distinguishes the remake is not the fact of its being a repetition, rather the fact of its being a precise institutional form of the structure of repetition, what I am calling the "quotation effect" or "citation effect," the citationality or iterability, that exists in and for every film.

The particular case of the remake that I remark upon here is that of the French film reconstituted as Hollywood product. Now, given that something like the Hollywood film or the "classic narrative film" seeks to erase the traces of its own production, and given that, as I have just maintained, after Derrida, the form of production of any mark can be called, between quotation marks, "writing," then it stands to reason that what a Hollywood remake would seek to erase from a French film would be precisely the traces of writing. For purposes of economy, shortly to be explained, I shall concentrate that idea by proposing the following self-evidence: what the Hollywood remake seeks to have erased from a French film is quite simply the subtitles. I can hear the reproach that my argument, quoted from

Derrida, for an idea of "writing" as trace that belongs to every mark, is negated or at least rendered seriously reductive by this recourse to writing in the literal sense of words upon the screen representing a translation of what can be heard on the sound track. However, my strategy has its own logic, namely, that it is the particularly explicit and privileged manifestation of the structure of writing that is the subtitle that enables me to develop the sense of the remake and remark, and that for the following reasons.

First, the subtitles do not—or at least the same ones do not—appear in the "original" foreign language version. When they do appear, as for instance in the English-language version, they show the film "in process," in production if you will: in the process of being transposed, translated, exported. They show that in being exported the film explicitly reveals its supplementary structure, its iterability, its (de) recontextualization. As a result the film might be said to come apart at a most basic level of cinema, namely, in the combination of image and sound tracks. Once subtitles are added the sound track reveals its difference from the image track—the seamlessness of spoken dialogue and moving lips is rent—but it does so on the level of the image track such that the seamlessness of the image track itself as coherent or intact reproduction of the real, as uniform visual surface and depth, is also rent.

Second, as I have noted (and I am saying nothing but the obvious here, nothing that has not already been observed or said, for I am quite simply quoting), the subtitles offer a translation of what is heard on the sound track, and as such they repeat the spoken sound track and so repeat the structure of iterability of the film. For in writing itself and in automatically being rewritten, the film translates itself, repeats itself with a difference, recontextualizes itself to a foreign place within itself. But the repeating effect is redoubled as it is reflected in the inversion[1] of the translated subtitles. The subtitles provide an abyssal form of that iterability by being inserted into the film or inscribed on the surface of the film; by appearing at the bottom of the screen they cause the bottom of the film to fall out.

Last, the translation that is the subtitles renders explicit the particular form of transposition that the Hollywood remake of a foreign film involves, namely, its removal to a more familiar place—a tramp falls into a Beverly Hills swimming pool instead of the Seine (Down and Out in Beverly Hills [1985], Boudu sauvé des eaux [1932]), a Las Vegas petty criminal falls for a French architecture student instead of a French existentialist hero falling for an American student and would-be journalist (Breathless [1983], A bout de souffle [1959]), three men are reset with their baby in America (Trois hommes et un couffin [1985], Three Men and a Baby [1987], like the cousins in love (Cousin, cousine [1975], Cousins [1989], like the recidivist female punk heroine called in to work for this government (La Femme Nikita [1991], Point of No Return [1993]), and so on. The remake neutralizes the otherness

of the foreign film, in general, but in no way more clearly than by effacing the subtitles. However, the paradox is that in erasing the effects of otherness, in removing the subtitles, Hollywood is duped into believing it has restored the seamlessness of a coherent, intact, and consumable image (and sound). It is unaware that it is working within the structure of the supplement and adding to, rather than subtracting from, the play of differences. The film Hollywood produces becomes enfolded into the abyss that is the subtitles of the original film. As a translation and transposition of the foreign original, it takes the place of the explicit form of that foreignness that inhabits the subtitles, it inscribes itself within the structure of noncoherence and nonintegrality, and, in transferring the film to a familiar context, however much it might presume to erase those effects of difference, it simply carries them over into the new product. That is, in any case, my contention, and I would like to explore it further through the remaking of Godard's A bout de souffle into Jim McBride's Breathless .[2]

Godard's film is quite obviously a privileged object for this discussion. It is a film that is less obviously concerned with the erasure of the traces of its own production than many others, although more so than other Godard films. And it is a film that has been given a thoroughly Derridean reading by Marie-Claire Ropars in her exemplary article "The Graphic in Filmic Writing: A bout de souffle or the Erratic Alphabet." But for these same reasons it is a highly unusual candidate for a Hollywood remake. Given the level of its "invention" when it appeared in 1959, its use of the jump cut, its borrowings from film noir and Hollywood, its self-reflexivity in general, it would seem to present a number of quandaries for whomever sought to make it over in the early eighties, inevitably raising the questions of neutralization and domestication. Dated as a revolutionary film, as one of a group of films that brought in the New Wave, but also dated by that historical reference, it could not but represent a problem of transposition, the problem of transposition and translation, the problem of the remake as remark. Although the film was made by a director known for his independence, and although McBride argued strongly for the right to remake the film and fought hard to produce something worthy of the original (cf. McBride, 1983), the American Breathless met with a lukewarm critical reception on both sides of the Atlantic, being dismissed as academic and certainly "not Godard."

However, I find what results to be particularly interesting: on the one hand McBride's film demonstrates the practical compromise of a film that has retained something of the "hip" quality of Godard's film but privileges the narrative structure more than does the French original, while on the other hand it reveals that what I have just called a "compromise," putting the word between quotation marks, is a fact of any film and any remake: it

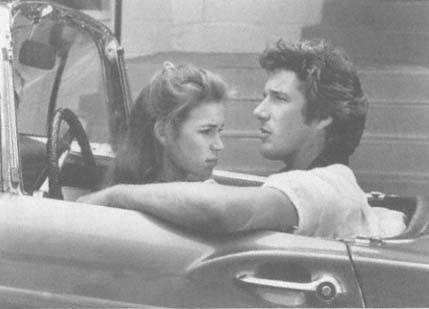

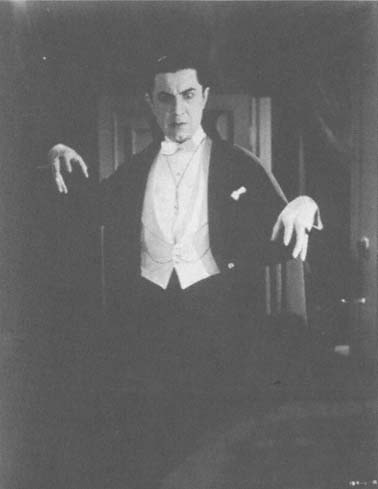

Figure 18.

Jean-Paul Belmondo and Jean Seberg capture the cross-cultural

playfulness of postmodern young love in Godard's Breathless (1959).

necessarily both covers and fails to cover the discontinuities or incoherences that structure it; it can only ever repeat itself as difference and inscribe those differences in the process of its writing. In other words, because of the multiple play of otherness that works so explicitly through A bout de souffle , two things occur: the first is another self-evidence, simply that not all the otherness gets neutralized; the second is the other side of that, namely, that otherness can never be neutralized, it will only ever reinscribe itself. Breathless is something of the dilemma those ideas represent.

In A bout de souffle small-time gangster Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo) has had a brief affair with the American student, newspaper girl, and aspiring journalist Patricia Fracchini (Jean Seberg) on the Côte d'Azur. (See figure 18.) He halfheartedly kills a policeman, returns to Paris in order to fetch Patricia and flee to Italy, but is held up by her tergiversations and a check he can't cash and is finally killed by the police after she denounces him. In Breathless Jesse Lujack (Richard Gere) has an affair with French architectural student Monica Poiccard (Valérie Kaprisky) in Vegas, even more "accidentally" kills a highway patrolman and returns to Los

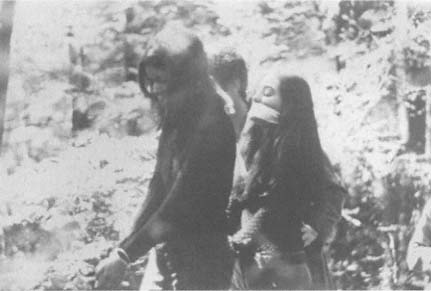

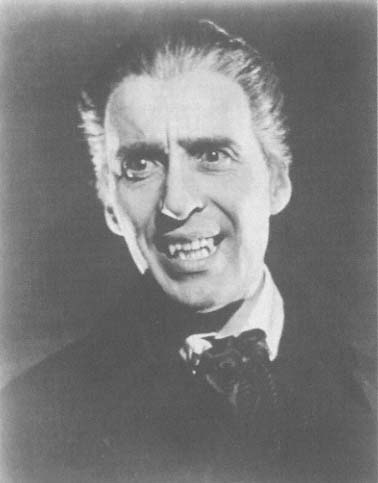

Figure 19.

Richard Gere and Valerie Kaprisky pause while on the run

in Jim McBride's reverse-role remake of Breathless (1983).

Angeles to fetch her and head for Mexico. (See figure 19.) She also denounces him and he is presumably shot, although, as we shall see, the final frame does not show it.

One could discourse at length on the slight and not-so-slight differences between the two versions. Here are some of them: whereas Poiccard wants to be Bogart, Lujack wants to be Jerry Lee Lewis or the comic-book hero the Silver Surfer; whereas in the French version there is a long "seduction" scene in the cramped quarters of Patricia's Paris apartment, in the American version this scene takes place between the large rooms and swimming pool of a Los Angeles apartment block; whereas the Paris detectives say "[O]n ne plaisante pas avec la police parisienne" ("[O]ne doesn't kid around with the Paris police"), the American says "Don't F-U-C-K with the L-A-P-D"; whereas in Godard's film it is Godard himself who plays the part of a passerby who recognizes the gangster from a newspaper photograph, I have no idea whether the tramp on the steps of a church who does the same is Jim McBride; whereas it is the American woman who introduces the Frenchman to William Faulkner's work in Godard's film, it is the Frenchwoman who introduces the same to the American in Breathless . On the basis of those differences one might begin to make an argument concerning

McBride's adaptation of Godard's film, his domestication or neutralization of it. One might refer to the less marginalized, more institutionalized female figure that has the effect of making the narrative less psychologically convincing—Monica seems much "straighter" than Patricia, less likely to be seduced by Jesse, who appears in turn as more of a boor than Michel; or to the compromise required by changing standards of cultural literacy—Faulkner is considered to be enough of a foreign reference for an American audience without having recourse to some canonical example from French literature. But the explanations for such differences would have, somehow, to collaborate with that which they sought to describe or critique, to some extent explaining away the differences by taking into account the "practical" considerations of adaptation: changes in history as well as geography (De Gaulle's France on the cusp of the sixties versus Reagan's eighties); the desire for a psychological contrast that has Monica fascinated and seduced by someone totally opposite; the importance of the quotation from Faulkner in its own right ("Between grief and nothing I will take grief"). In other words in accounting for these sorts of differences one would get caught up precisely in the question of differences between one film and another, reaching down to the smallest details of the texts but overlooking for the most part the matter of differences within the text, its intrinsic remarkability.

In one respect the differences just referred to would lead us to such a remarkability, namely, in respect to what has been called the self-reflexivity of Godard's A bout de souffle , its constant reference to matters cinematic. However discussion of such references does not necessarily remove us from the framework of complicit explanation just referred to. While it is true that Bogart has been replaced by Jerry Lee Lewis, and film posters and young people selling cinema journals do not appear in or out of the background of Breathless , Hollywood can never be far from the foreground of a fantasy romance set in Los Angeles. And in any case references to cinema are not absent from McBride's film: there is an Antonioni-like frame of Monica standing at a bus stop that advertises the Hollywood Wax Museum, in front of a military cemetery; the final scene takes place in the ruins of Errol Flynn's "Pines"; and there is the sequence in the movie theater, much more developed than in Godard's film, that I shall return to shortly. The argument is easily made that it would not be a good artistic choice for a film made in the eighties to be self-conscious in the same way as one that was like a new wave breaking in 1959. Similarly, Godard's signatory appearance in his own film in fact says little. Presumably he was no more recognizable to a 1959 French audience than Jim McBride would have been to us in 1983. And what would a contemporary audience raised on Hollywood's permanent fear of self-recognition do with a camera jerking across the sky to the sound of gunshots as Godard's Michel pretends to shoot, like

a converse of Camus's outsider, at the blinding sun, or with a Michel who turns to the camera as he drives to say, "If you don't like the sea, if you don't like mountains, if you don't like cities, then go and get fucked!" (["allez vous fair foutre!"]—this last invective already sanitized by a milder translation in the subtitles)? These things have attained historical inscription as marks of Godard's filmmaking practice that can not easily be translated.[3] So the discussion would bring us back to questions of compromise and problems of translation without, for all that, allowing us to think the questions through very far.

Yet if we read such references less as self-consciousness or self-reflexivity and more as self-iterability, as cinema quoting itself, drawing attention to itself as effects of writing, such things come to form the basis for another level of dislocations that, as I have suggested, turn the question around. The film doesn't just say "I am a film, I am an object-in-construction being presented to you as a self-constituted commodity," it also says: "I am a series of images within images, sounds within sounds, subject to constant recontextualization. The images that constitute me are constantly undercut, in the process of their constitution, by their inability to define themselves as presences without at the same time falling prey to effects heterogeneous to those presumed definitions. Thus I am a series of images within images that are never just or never completely images, never untouched by radical difference, and never purely pictorial without also being graphic. There is never the immediacy of perceived objects without also the presence of hieroglyphic labyrinths; thus I am always graphic in two senses, that of the pictorial and that of the written." The still image of Bogart on the poster of The Harder They Fall and of Michel imitating the way Bogie passed his thumb across his lips becomes not just an image of a poorly formed identity, a petty criminal with personality problems trying to be a larger-than-life celluloid hero, but a type of freeze-frame that arrests the narrative flow, a silence within the noise and music of the continuous images, a problem of identity for the images themselves. The image of Bogart has inscribed upon it like a title or a signature the image of Poiccard, and vice versa. Similarly, when Godard playing a man on the street looks at a photograph in the newspaper he is reading, then looks at Michel, then back at the newspaper photograph, then crosses the street to show the same photograph to two policemen, Godard doesn't just sign his film and wink at the audience in the manner of Hitchcock. He transfers the question of identity posed at the level of the image—and repeated here by means of the competing images of Michel, still and moving, arrested and passing, here and there, past and present, print and celluloid, written and pictorial—he transfers that question of identity to the level of his film as a whole. Once Godard is in it, on its surface, it can no longer simply be a film he has made; nor does it become instead performance art; rather his appearance as a character point-

ing at an image in another medium, inscribing his body or his finger on its surface, is like a name written across his whole film that erases its wholeness and renders it irredeemably heterogeneous. Any translation or transposition of the film will henceforth necessarily be a translation of that heterogeneity, a translation from foreignness to foreignness.

In her article, Marie-Claire Ropars has traced such effects through the play of language in A bout de souffle , especially the play of the written word within the image. Although she in no way limits the idea of writing to these chance or designed appearances of the written word, her strategy enables her to develop the notion of an image constantly worked upon and over by its others. It is her conclusion that I have used as the basis for my argument here, namely, that what the film offers in the final analysis is a question about translation, a problem with translation. All the way through, A bout de souffle keeps coming back to the matter of inter- or translinguistic usage. And it would be incorrect to presume that that is all a function of a relationship between a less-than-bilingual American woman and a Frenchman. Patricia does get her French wrong from time to time, but Michel also corrects the usage of another woman, presumed to be French, whose apartment he visits in order to steal some money. And he himself resorts more than once to the Swiss usage for the numerals seventy and eighty (one could hear that as another signing by Godard, who is of Swiss origin). There is no pure French in the film, but always effects of translation, within a language, between languages.

However, it is in the final exchange of the film that, as Marie-Claire Ropars points out, the matter becomes concentrated, bringing with it a complicated thematics of misogyny that has the female bear the weight of linguistic otherness (156–58). "Tu es vraiment dégueulasse " ("You are really shitty," my translation), Michel says as he lies dying. When Patricia asks the policeman what he said he replies "Il a dit: 'Vous êtes vraiment une dégueulasse' " ("He said: You are really an arsehole" ["bitch" in subtitles]). This is no simple quotation of Michel's words by the policeman. First, he gives the effect of reported speech and so changes the familiar "tu" to the formal "vous," but at the same omits the "que " ("that") so that syntactically his words amount to a quotation of direct speech. But his quotation is a misquote, for he inserts an indefinite article before "dégueulasse " so that that adjective becomes a noun with a stronger sense—"shitty" becomes "arsehole" or something similar, just as "con " ("stupid") as adjective becomes "cunt" as a noun. Patricia is left asking "Qu'est-ce que c'est 'dégueulasse'? " ("What does 'dégueulasse ' mean?"), a question that receives no response, except in the subtitles of the English-language version where many of the preceding subtleties take on quite different nuances.[4]

In McBride's Breathless there are of course similar linguistic transpositions. First of all Monica has a foreign version of the French name "Monique."

She has to have Jesse explain to her what jinxed means, and what a desperado is, although in the latter case the word should be evident enough to a speaker of a Romance language. She refers to Jesse as "taré ," another word that can alternate between an adjective and a noun—"It means crazy, a disgusting person, jerk," she explains—and he appropriates the word for his own use. But in the American film, as in the French, the most interesting linguistic play occurs in the more precise form of the misquotation, in terms of a translation that occurs more strictly within the space of the same.

The first example comes from the scene in the cinema. Here, the characters enter the space behind the screen and watch the images in mirrored form playing in black and white before them. This is first of all, it seems to me, a more radical mise en abyme of the cinematic than anything in A bout de souffle . There are competing cinematic surfaces, inscribing their differences, on almost the same visual plane—this isn't just characters in a film watching a film. The images seen on the screen, from Joseph H. Lewis's Gun Crazy , occur as an inverse background, a sort of subtitle or translation, to the film Breathless —Lewis's characters are speaking of the high stakes in their relationship as Jesse and Monica begin to make love in the moments after a close escape from the police. But that effect is inverted again when Jesse and Monica in turn inscribe themselves within the film they are watching, back to front, especially by means of Monica's quoting of the woman within it. She repeats the words we have just heard from Gun Crazy —"I don't want to be afraid of life or anything else"—to which Jesse replies, "You don't have to be afraid of nothing."

What the quotation has set up here is something quite different from a repetition, a transposition of words from one mouth to another. It is rather a recontextualization radical enough to amount to a reversal, an inversion, according to what I shall call, for reasons that the rest of what I have to say will explain, a logic of the chiasmus.[5] It reoccurs quite clearly at the end of Breathless . After Monica returns to inform Jesse she has denounced him to the police, she tells him to leave so as not to be apprehended. He wants to stay, because he loves her, and believes her to love him. "Do you love me?" he asks, then demands that she reply: "Say it!" When she doesn't, he turns the logic around and at the same time demands that she quote him: "Say you don't love me and then I'll go." She replies and quotes him: "I don't love you," but unconvincingly enough for it to be read by Jesse as meaning the opposite: "Liar!" he declares, and deciding that she loves him, rushes off to pick up the money from Berrutti and return to flee or be with her. Thus the translations and quotations run to and fro within the structure of iterability to the extent that the repetitions become inversions, contresens . Something similar happens in A bout de souffle as Patricia reverses the position of the adjective in the name of the street, Rue Campagne Première , when she denounces Michel, making the correct linguistic assump-

tion that "premier" as adjective precedes the noun, occurring in the weak position, whereas in this case it follows. Her error works as a corollary to her attempts to fathom the logic of her feelings for him, with her finally settling on the inverted formula of "Since I am mean to you I am not in love with you."

Once iterability or the remarking effect comes into play, and it does so from the beginning and never stops doing so, then any translation or transposition—that which occurs in and from the beginning as much as that occurring in the case of a remake—involves the sorts of cross-purposes just outlined. Translation necessarily occurs as a chiasmus between the homogeneity of a single sense and the heterogeneity of a divided sense: like the homogeneity of a self-evident image and the heterogeneity of that same image crossed over and crossed out by things supposedly foreign to it. There can never be a faithful remake, and not just because Hollywood demands compromises or because things get lost in translation or mistakes occur, but because there can never be a simple original uncomplicated by the structure of the remake, by such effects of self-division.

In the final analysis it no longer comes down to a question of what Breathless tries, or doesn't try to do with A bout de souffle , or even what it does or doesn't do with it. Thus in returning to the final and perhaps most important divergence between the two films, Breathless' choice of a musical subtext over the French film's use of cinema, Jerry Lee Lewis instead of Bogart, I wish above all to emphasize once more the idea of chiastic self-division that renders the American film irretrievably different from the French one, and that, paradoxically, in spite of any attempts by Hollywood to produce a more domesticated version of Godard, renders it irretrievably different from itself and eminently Godardian. On one level it comes down to the impressive work of Jack Nitzsche on the sound track and his association of a Philip Glass theme with the female character as a counterpoint to Jerry Lee Lewis for Jesse. But I doubt whether the title of that theme, "Openings," from Glassworks had anything to do with his choice. However it is by means of the musical openings produced on the sound track that McBride's Breathless breaks with Hollywood in favor of something more like Godard at the same time that it comes together as a film.

Although Godard's use of sound always recognized its force as an otherness "within" the visual field of film, in some of the films that marked his return to commercial cinema in the early eighties, contemporaneous with Breathless , the work on sound became concentrated in terms of music. That was so for Sauve qui peut (la vie ) (1979 [Every Man for Himself ]) and more explicitly for Prénom Carmen (1983 [First Name Carmen ]).[6] The effect is to seriously disrupt the distinctions between layers of the sound track on the one hand, and sound and image tracks on the other hand. A version of the same thing occurs with the sound track at the end of Breathless . The French

ending that has Michel shot in the back by the police and running for his life but to his death at the end of the Rue Campagne Première is replaced by a Jesse pausing over a gun on the ground, being urged not to pick it up by a frantic Monica and by the police who have their guns trained on him. He suddenly turns to face the police and breaks into a mimed rendition of Jerry Lee Lewis's "Breathless." The sound track music, which during this scene has used an increasingly syrupy strings rendition of Glass's minimalist piano piece "Openings," is interrupted by the beat and melody of the Lewis song; then the two compete in a melodic and rhythmic crisscross as Jesse's mime veers into a sort of expressionistic limbo. The Lewis song reasserts itself with Jesse facing Monica and singing the word from its title and the title of the film before stooping to pick up the gun and again face the police and his death.

By foregrounding the music in this way, Breathless goes beyond the self-consciousness of Jesse's worship and imitation of Jerry Lee Lewis and in a very Godardian fashion brings the music track from its offscreen position into the narrative and onto the screen. Conversely, the visual track is crossed by the sound track and the narrative is frozen in a ghostly mime. Whereas the Glass theme has been used as a pensive "feminine" contrast to the impulsive and macho Lewis songs, presumed to be never more than background, here the counterpoint suddenly takes itself literally, leading to the chiastic effect of this climax. If one wanted, one could read in the word "counterpoint" precisely such a musical and graphic chiasmus by translating it or transposing it as follows: the word "point" would come to be the musical or rhythmic equivalent of the word "trait," privileged by Derrida (1980, 1987) to express the heterogeneity of the line (the French word trait means both brushstroke and stroke of the pen), the divisibility of the pictorial by the graphic and vice versa. "Point" would then mean both "dot" and "beat," and "counterpoint" would express the crossing of one by the other. The counterpoint of Glass's "Openings" would then become the punctuating effect of music upon the narrative and visuals in general that occurs as that piece struggles against the beat of Jerry Lee Lewis in the final shots. It would be like the rudimentary writing effect that is the dot inserting itself as foreign otherness on the screen and on the film. As a result the film is frozen in a composition—the climactic halting of the narrative flow—that is also a transposition or translation: the crossing of the two musical themes and their imposition upon that narrative. The final sequence of Breathless thus works as an opening onto a cinematic process—an opening of the film onto itself and a crossing of the film by itself, a remaking of the marks of cinema—that can be read as far more radical than anything in A bout de souffle .

The story of the remaking of Godard's groundbreaking New Wave film is not finally about how faithful the American copy manages to be or how

original it manages to be, two paradoxical qualities requested or required of a remake. It is rather about how any film, from the explicitly Brechtian to the most seamless Hollywood product, works as a quotation of itself, the repetition or rehearsing of its own differences. The story of A bout de souffle , carried over to Breathless is, after all, about a problem with a check, a check that can't be cashed, a written promise that can't be immediately fulfilled in the form of hard currency. It is therefore about a problem with different media within a system of exchange, like the visual and audio media of cinema, and also a problem with signatures. The problem Michel faces is that although the check is made out to him, it is crossed, made nonnegotiable, requiring it to be processed through the institutional rigors of a bank account. It has lines drawn or written across it and needs more writing and stamping on the back before it can be of any use to him. It is also crossed in the sense suggested by the French word barré , meaning blocked, immobilized. In the American Breathless the problem is similar, although it is the check itself, as written monetary form—or written monetary form different from cash, since there is no nonwritten form—that holds Jesse up and allows the police to close in on him. Either way, the check requires some form of endorsement, a structure that can be called—especially since this is a check that travels to a foreign land, like a traveler's check—that of the countersignature. But, as Derrida (1982, 1984) has shown, what the countersignature does in reaffirming the authenticity of the original signature is subvert that very authenticity by showing the presumed singular and idiosyncratic event of the signature—what makes it mine and the written code for my proper name—to be repeatable and thus subject to the same decontextualizations, in this case especially forgery, as any sign or line. The countersignature is a repetition of the same that ushers in the structure of difference; it is a quotation of the original that is a translation and transposition of it.

The American film Breathless might be read as an attempt to cash in on the credit established by Godard's film, to cash it and at the same time process it through the Hollywood institution, an institution concerned with nothing more than what is bankable. But the check stays crossed, the film remains written, for it cannot be otherwise. On the other side, once it has crossed the Atlantic, in spite of the translations and inversions, there are more crossings, there is more writing. Whichever film one reads first, whichever version is taken to be the original, the heterogeneities of cinema continue to cross both ways; the countersignature divides itself in a play of writing. A bout de souffle, "Breathless" the subtitled version, Breathless the American version, and "Breathless" the song by Jerry Lee Lewis, as well as all the versions that I have quoted in writing about it here, are caught up like so many stolen cars, in such a complicated interchange, something of the shape of which this article has sought to outline.

Works Cited

Brunette, Peter, and David Wills. Screen/Play: Derrida and Film Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

Derrida, Jacques. "The Law of Genre." In Glyph 7 , 202–29. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980.

———. "Living On / Borderlines." In Deconstruction and Criticism , edited by Harold Bloom et al., 75–176. New York: Seabury Press, 1979.

———. Signsponge/Signéponge. Translated by Richard Rand. New York: Columbia University Press, 1984.

———. The Truth in Painting. Translated by Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Falkenberg, Pamela. "'Hollywood' and the "Art Cinema' as a Bipolar Modeling System: A bout de souffle and Breathless." Wide Angle 7 , no. 3 (1985): 44–53.

McBride, Jim. "Sortie des Marges: entretien avec Jim McBride." Cahiers du cinéma 350 (1983): 31–34, 64–66.

Ropars-Wuilleumier, Marie-Claire. "The Graphic in Filmic Writing: A bout de souffle, or the Erratic Alphabet." Enclitic 5, no. 2; 6, no. 1 (1981–82), 147–61.

Wills, David. "Carmen: Sound/Effect." Cinema Journal 25, no. 4 (1986): 33–43.

———. "Representing Silence (in Godard)." In Essays in Honour of Keith Val Sinclair, edited by Bruce Merry, 180–92 Townsville: James Cook University, 1991.

Ten—

The Spring, Defiled:

Ingmar Bergman's Virgin Spring and Wes Craven's Last House on the Left

Michael Brashinsky

Nothing, neither among the elements nor within the system, is anywhere ever simply present or absent. There are only, everywhere, differences and traces of traces.

Jacques Derrida, "Positions"

In 1972, Cries and Whispers, Ingmar Bergman's thirty-fourth film, was released to universal acclaim, followed by a foreign-language Academy Award. The same year, Wes Craven, a neophyte, made The Last House on the Left, a picture that even today, after the near disappearance of drive-ins, can be found in selected video stores only under the category "Drive-In Horror." If merely for this utter coincidence, the two names would never meet on the same page of film history. But they do, for, incredibly, The Last House on the Left is a remake of The Virgin Spring, a film Bergman had made thirteen years earlier.

This fact, while widely publicized in film literature from Gerald Mast's Short History of the Movies[1] to popular video guides,[2] goes unannounced in The Last House on the Left . Instead the legend reads, "The events you are about to witness are true. Names and locations have been changed to protect those individuals still living."

Why deceive us? Or is it really a deception? In the realm of doubling visions and mutating images, which is precisely what the culture that favors the remake should be, the question, Why wouldn't a filmmaker admit to remaking a classic? could be only another way of phrasing the questions, Why remake classics at all? and What is the remake?

The remake is not a genre, nor is it a kind of film. It is neither a newly filmed old script nor a new script based on an old one. It is nothing but a film based on another film that is itself a system of narrative and cinematic properties.

As such, the remake can be seen among aesthetic expressions built on reinterpretation and engaged in a "trialogue" with nature and a culture

other than their own. But unlike the stage production of a play or the film adaptation of a literary work, the remake interprets the work of the same medium and thus bares its own secondariness.[3] It skips the act of meta-aesthetic transition in which, according to the widely accepted modernist prejudice, originality begins. This, of course, is what the remake should be praised rather than blamed for. It provides us with countless clues to the medium, the culture, and ourselves that would be eclipsed by the study of what the original material has gained or lost in passage from one medium to another.

Indeed, Hamlet and Medea would not be classics had they not offered a vast scope of options for interpretation. We have seen Hamlet-poets and Hamlet-impotents, Hamlet-soldiers and Hamlet-nerds, Hamlet-rebels and Hamlet-fascists. In Shakespeare's play, theater sees a literary "empty space" (to use Peter Brook's famous formula) to be filled with a new theatrical content, and the magic of this space is that its shape, size, and texture seldom say no to new meanings. But plays are intended to be reinterpreted on stage. Films are not made to serve as sources for other films, just as books are not written to be rewritten, unless by Pierre Menard, the father of all remakes, who resolved to compose Don Quixote —not just "another Don Quixote, " but "the Don Quixote "—as if it had never been done before.

The gap between the worlds of the remake and other aesthetic translations is not as technological as it is cultural. Stage and screen adaptation existed from the beginning of their respective arts. The remake has become the most explicit gesture of a culture that finds its psyche in the Other and cannot express itself through anything but a quote. In this culture's tired eyes, life does not imitate art—art has replaced life. Michelangelo and Fellini, Bach and Picasso are there, just as the air and the trees, and there is no pretending otherwise. Trying to avoid Oedipus when telling a story of a man who tried to avoid his fate would be as senseless today as setting up a camera in a bathroom and dismissing Hitchcock's eye in the drain. Culture, that Ortega y Gasset's window separating an artist from the garden, has become a garden of its own, and its flora, all those fleurs du mal, leaves of grass, and rose tattoos beat the natural vegetation. Similarly, The Virgin Spring is as "real" for the postmodern imagination as any other spring, and Wes Craven is as telling as he is teasing when he suggests that his film is based on "a true story."

This story is not true, and not only because it is too implausible and contrived to seem real. The Last House on the Left is in fact an uncredited remake ("a rip-off," according to Leonard Maltin[4] ) of The Virgin Spring, and the first evidence it offers to us is, clearly, the narrative.

Stripped of all imagery and magic down to an austere plot, the Last House narrative is, in fact, closer to its source than those of such admitted remakes as Scarface (1932, 1983), Cat People (1942, 1982) and The Fly (1958, 1986).

In both films, an innocent teenage girl, the only child of loving parents, leaves home for a weekend excursion, accompanied by a shrewd confidante. On the road, she is brutally raped and murdered by a gang of criminals. (In The Last House on the Left, the girlfriend is similarly attacked and killed, providing one of the few notable deviations from the original). Fleeing the scene of the crime, the killers stumble upon their victim's home and stay overnight (a coincidence equally unmotivated in both scenarios) only to meet a merciless retribution from the girl's father.

If this is a story of crime and punishment, then neither film is about its story. Nor is it about the young, the girls on whom each picture centers briefly only to liquidate them and move on. Here the narrative parallels between films end.

As if it were a western, the black-and-white Virgin Spring is ruled by dichotomy. It juxtaposes the virgin, Catholic, and blonde Karin, who is killed on her way to mass, with the pregnant, pagan, and brunette Ingeri, who survives to lament and possibly to convert. Preoccupied with moral (and other) dilemmas, Bergman gives his pain and lens to the father, who is played by the then-thirty-year-old Max von Sydow as an ascetic warrior undergoing a tremendous internal turmoil. He is torn between the pagan God he has renounced and the Christian God he does not understand. The killers are godless, but so is the father's eye-for-an-eye revenge. A hero of a classical tragedy, seen through a prism of modern culture—Kierkegaard, Dostoyevsky, Camus—he kills because the God he has chosen has not only left him but has also left him no choice. Ultimately, The Virgin Spring becomes a story of a shattered faith redeemed in repentance.

In The Last House on the Left, Dr. Collingwood, played by the unforgettably bland Gaylord St. James, is all but faceless compared to his "paternal" model. He also takes over the initiative in the end, yet not because his self is tragically conflicted but because it is his turn to be violent. Violence in Wes Craven's films is the measure of all things; it is the last "means of communication" left for his characters to respond to the cruelty of the others and the world.[5] Rape and murder and then revenge—these climactic eruptions of violence, so crumpled and clumsy in The Virgin Spring that the attackers and not the victims seem to be suffering from the mess—are what The Last House on the Left dwells on. Not off to the church and not "after the rainbow," as the song on the sound track suggests—the girl is after a rock band called "Blood Lust," and the film insinuates that the director made it to the concert while his heroine didn't. Unlike moralist Bergman, for whom any savagery is senseless, the post-Vietnam "immoralist" Craven provides the world's violence with a cause as appalling as its absence in The Virgin Spring: "We're gonna have some fun," promises the Mansonesque killer before he rapes. Conversely, where Bergman takes great pains to establish motives for the father's revenge, Craven throws his doctor into a

whirlpool of unwarranted cruelty and gives him a hand only when it comes to choosing a weapon simply because there is nothing else left for him to do.

Just as The Virgin Spring was a tale of faith, The Last House on the Left becomes a tale of havoc. Order returns at the end of The Virgin Spring; it never does at the end of The Last House . But isn't it the incentive of every remake to tell the same story with a different meaning?

The otherness of the meaning, of course, is visible only to the informed. Clearly, one must be familiar with the original to understand what the remake alludes, or bids adieu, to. Like one of those tricky airport billboards that reads "Welcome" or "Have a Good Flight," depending on the passenger's direction, the remake says one thing when read as an original work and another when seen in retrospect, through the lens of its source.

The Last House is as full of hidden (and not so hidden), playful (and straight-faced) allusions to its prototype as its landscape is full of springs. Just like the coquettish blonde Karin, who insisted on the white Sunday dress that was a bit too immodest for a medieval Swedish maid, the coquettish blonde Mary Collingwood argues with her parents about clothing. She puts on an outfit to which her father remarks, "What, no bra?! You can see nipples!" propelling a lengthy discussion on "tits." Later, the delinquent kid—or "little toad," as his fugitive parent refers to him—says he wants to be a frog. The character does not mean what Wes Craven does: in The Virgin Spring, a toad, squashed by the ill-natured Ingeri into a loaf of bread, is found by the boy. Having latently recognized himself in the amphibian, the urchin repents, just as his offspring in 1972 will. Neither one lives to see the end of his film.[6]

Here, at the stage of narrative interaction, many remakes would stop. But what would do in the screenwriter's heaven of Hollywood mainstream, where remaking a film is often synonymous to retelling the story, was not good enough for Wes Craven, a pioneer of rediscovery and a rebel with a cause to dare the guru of European film auteur.

If The Virgin Spring were a tapestry it would be made of canvas, the coarseness of which would only be highlighted by its artist's translucent style. Canvas and wood are two basic materials this universe is made of. Fire and water are two elements that combat one another here for man's soul. Sven Nykvist's camera, solemnly frontal, creates an image as pure and minimalist as the world it depicts. This world does not know any middle ground, just as its inhabitants are unaware of compromise. If it's raining here, watch for the Deluge; if it's hurting, await a bloodshed. In this world, the woods are teeming with ravens and goblins. The ravens caw; the goblins see "three dead men riding north"; both prophesy ill. Everything is an omen here,

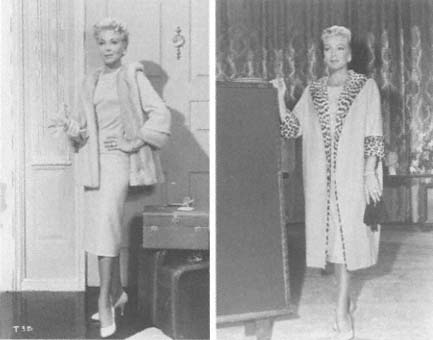

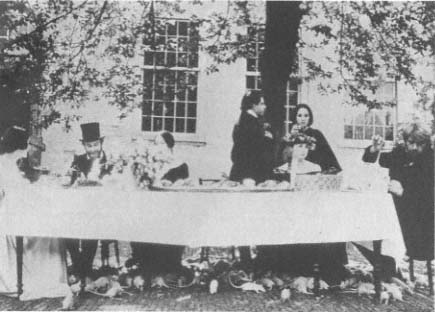

Figure 20.

One of the most startling film rituals ever: we see the father's sacred cleansing

before the sacrificial killing. Max von Sydow and Brigitta Pettersson star

in Ingmar Bergman's The Virgin Spring .

and nature speaks to man. Pagan Ingeri begs Karin to turn back, for "the forest is so black." Karin doesn't listen, and pays for it.

There is nothing this world values more than a ritual. A film whose legendary time spans from dawn to dawn, The Virgin Spring begins with Ingeri starting a fire while conjuring up the god Odin and ends with the father's invocation of the Lord. In between, there is one of the most startling film rituals ever: the father's sacred cleansing bath before the sacrificial killing. (See figure 20.) The father wants to be Christian, and this world—pagan, primitive, fossil—does not make it easy for him. Another word for this world would be mythic, which seems to entirely match with Bergman's conception, inspired, according to the opening credit, by the fourteenth-century Swedish legend. In the realm of myth, all dimensions of The Virgin Spring —thematic and formal—coincide and intersect in an ultimately tuneful order.

The remake's bond with cultural mythology is as solid as it is basic. What a serious, conscious remaker sees in the source film is an individual expression of the myth to be remade. From the narrative, through the filmic prop-

erties, to the underlying cultural myth lies the trajectory of any remake that is of interest to thinkers and not just to financiers.

Of course, there are myths, and then, there are myths. The kind of myth-making in which the remake is involved is "low" and popular, not "high" and classical. But what is the difference? What is the difference between Orestes and James Bond? Both are great spokesmen for their times. Both are serial heroes. Neither can breathe outside the genre structure.[7]

There was nothing that popular culture, this spoiled and prodigal offspring of romanticism, would seize more eagerly from its classical parent than the notion of genre: genre as a formula and genre as a model channel, or conductor, for myth. The convenient beauty of the genre is that its formulaic and mythical qualities are not discrepant. Genre in fact does in culture what no individual genius could: it formulates myths.

This is why most remakes are genre films. The self-conscious, referential culture of the remake, constantly in search of codes, finds a dual code in the genre film to make over: the code of the individual source and the code of its genre. (Martin Scorsese's Cape Fear, for example, was not only a remake of J. Lee Thompson's picture but also of the thriller formula as a whole.) Even more significantly, genres do for remakers what sieves did for gold miners: they sort and retain, they distill the myths of the time.

When the myth of a genre (the frontier naïveté of the western, or the apocalyptic dread of the disaster film) does not match the myth of the time, the genre fades away. For the same reason some ideally formulaic genre offerings fade away untapped by remakers (the western in the 1980s, the "invasion film" after the end of the cold war).

But if the secret of a successful remake is chiefly in finding a perfect match between the genre and the epoch (which is true about many remakes, all based on genre films), this secret was of no use for Wes Craven in remaking The Virgin Spring, a film without a genre. Yet Craven, a director dressed to head the A list of B moviemaking, knew perfectly well what he was doing when he picked one of the most mythical films ever as his prototype. He found exactly what he wanted: a different kind of myth, a modernist myth, unscratched by popular culture. In Bergman's pure, distilled, and culturally virgin myth, Craven had a perfect spring to defile.

What in 1959 was the fourteenth century, becomes 1972 in 1972. And what in fourteenth-century Sweden was primeval forest, the realm of basic elements and instincts, in 1972 becomes an American suburb. (See figure 21.) Typically peaceful and sweet, typically boring and dull, typically middle class, it is decorated with integrally standard facades (on the outside) and requisitely moderate "abstract" prints (on the inside). Here, what looks like wood is actually Formica; what could be canvas is really nylon.

Yet Craven does not reduce the poetry of myth to mythless prose. Rather,

Figure 21.

The fourteenth-century prieval forest (The Virgin Spring, 1959) has

became an American suburb (The Last House on the Left, 1972)

in Wes Craven's remake of Bergman.

he embarks on a dimension no less mythological than Bergman's, but with different kinds of myths.

Suburbia, the citadel of normality in American culture, is where the myth of family values found refuge from society's nervous breakdown. An isolationist haven (ours is the last house on the left, which also could be the first house on the-right ), the suburb is a mutation of urban and rural mythologies. Neither city nor country, it appropriates (in the collective subconscious of its inhabitants) the best and the safest of both.

Never a paradise, but always a target, the suburb is a perfect setting for the bizarre, more so against the backdrop of nauseating and often fake familial serenity. In the 1950s, the suburb was the most sacred site that the rootless body snatchers could possibly invade; its invasion, therefore, was the scariest. In the early 1980s, the suburb, an ideal metaphor for neocon-servatist mentality, returned as a favorite location for science fiction and horror films, a scene most appropriate for the invasion of alien (Steven Spielberg's E.T. [1982]) or supernatural (Tobe Hooper's Poltergeist [1982]) forces. A few years later, David Lynch, the poet of provincial void, romanticized suburban evil by demolishing the suburban myth in Blue Velvet (1986).

The Last House on the Left, with a rock sound track that sounds as if it were

borrowed from Easy Rider (1969), is one of the first ventures into the renovated, postradical myth of the 1970s. It is also one of the first reactions to the defeat of the 1960s, coming from inside the generation that lost. A film with plenty of violence, it is also a film without suspense. It is not meant to frighten us or in any way involve us emotionally—something suspense cannot do without. A surgeon rather than a lyricist, Craven, who will return to suburbia in the more baroque but less personal Nightmare on Elm Street (1984), gives us nobody to identify with and maintains his own distance. What he sees is a society that has fallen asleep (or was put to sleep), a desensitized society to which Philip Kaufman in 1978 will find a perfect metaphor in the 1950s' Invasion of the Body Snatchers . This society is crushed here by the hippielike killers and, even more so, by its own chain-saw defense. That this chain saw belongs to another story and a different, "antisuburban" myth is precisely what Last House on the Left is about.

Hitchcock was only kidding when he began Psycho with a tale of theft that led nowhere. Craven's play is less elegant but more candid. In the opening, he also promises a different kind of movie, a "sweet sixteen" melodrama, with a fruity birthday cake, cute neighbors, and the indispensable generation gap, expressed in conflicting approaches to brassieres. These promises are as vain as they are essential for suburban utopia, absurdly solid and solidly absurd.

The wishful destruction crushes this sleepy world with a savage energy that makes Bergman's violence look like figure skating, just as Craven's handheld camera and jerky editing make Bergman's frontal grandeur look like an old master's frescos. When Mary's mother, a housewife with facial features all but washed out, bites off the assailant's penis, there can be no mistake: something went awry in this world. When Mary's father, who looks like the Reverend Billy Graham, splatters the rapist's brains all over his tacky furniture we know sweet suburbia is no more. Violent frenzy has invaded the myth of normality as it took over intellect in Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs (1971). Similarly, George Romero's crazed zombies snatched the bodies of loyal citizens.

In 1959, Ingmar Bergman made a film about a tragedy that inevitably accompanies the shift of mythologies, the passage of cultures. So, in 1972, did Wes Craven. Only his is a kind of tragedy that could be written not by Shakespeare but by Shakespeare's Fool: ruthlessly cynical and painfully funny.

As a postmodern artist has no other way to "interview" reality but through an interpreter of another culture, it is hard to imagine a remake made within the same cultural tier as the original. The cultures must vary, either in time, as is the case in The Thing (1951, 1982), The Fly (1958, 1986), Cape Fear (1962, 1992), and most other notable remakes, or in space, as it hap-

pens between Yojimbo (1961, Japan) and A Fistful of Dollars (1964, Italy), Seven Samurai (1954, Japan), The Magnificent Seven (1960, USA), and even George Cukor's Adam's Rib (1949, USA) and its Bulgarian remake (1956), and Rambo's First Blood (1982) and the Russian response to it, currently in production, in which an Afghan war vet comes out of his drunken oblivion to fight the evil of the world.[8] In any case, the remake remains a metacultural medium that has to cross borders, temporal or spatial, in order to connect.

The Last House on the Left at least tripled the shift. It switched from the 1950s to the 1970s, from European to American sensibility and, last but not least, from a militant, genreless auteurism to an excessively personal style of a B slasher movie before the genre went mainstream. Wes Craven's film met its prototype and interlocutor on the terrain of myth and proved that only mythless times will not be remade. If only one could imagine times like that. And if only one could believe that times like that deserved a remake.

Eleven—

Cinematic Makeovers and Cultural Border Crossings:

Kusturica's Time of the Gypsies and Coppola's Godfather and Godfather II

Andrew Horton

I think that the concept of border suggests something very subversive and unsettling. . . . [I]t means recognizing the multiple nature of our own identities.

Henry A. Giroux, Disturbing Pleasures

Dedicated to Gypsies, filmakers, and border crossers everywhere.

"Yes, this is a Gypsy Godfather, " wrote the Time reviewer Richard Corliss in 1990 when Time of the Gypsies, by the Bosnian-born Yugoslav director Emir Kusturica, was released in the United States after it won for him the Best Director award from the Cannes International Film Festival the previous year.

The reference to Coppola's 1972 hugely successful Mafia family epic based on the Mario Puzo novel and screenplay is more than an American critic's effort to interest a home audience in a quality foreign film. For Kusturica's gypsy tale, based on actual newspaper stories, turns out to be not only a transfixing glimpse at a "parade of ethnic eccentricity" (Hinson), but a hymn to world cinema at a time when television has become the more dominant form of presenting moving images. Finally, this Balkan recasting of Coppola's Godfather and Godfather II (it was made before Godfather III appeared) also manages to go beyond such intertextuality and international border crossings to emerge as a "Yugoslav" text reflective of the cinema of that troubled country that tragically no longer exists in any discernible form. In this essay I use Kusturica's captivating film as a case study in a larger consideration of cinematic remakes viewed from the triple perspective mentioned above: how a film from a non-English-speaking, third world country may drastically remake a Hollywood film (films in this case), how

such a film can also allude to the cinemas of other nations and thus in some way announce itself as a member of the discourse of "world cinema" while maintaining its own cultural integrity as, in part, seen by its allusions to the cinema of its own nation. Not all elements of such a complex case of border crossing, as cultural-cinema critics such as Henry A. Giroux have explored the term, can be thoroughly illustrated in such a short piece as this. But it is my hope that this essay furthers cross-cultural cinematic studies.

Rather than remake The Godfather in any overt sense, however, Kusturica, a Bosnian filmmaker from Sarajevo, has made over Coppola's work to reflect Kusturica's own personal and cultural (Yugoslav) interests. In fact, Kusturica has often used The Godfather more to point to contrasts than parallels, culturally and cinematically.

Most attention paid to cinematic remakes involves Hollywood films, which we can consider either from the purely capitalistic urge of the industry to make more profit on a proven product or, as Leo Braudy has suggested in his remarks in this collection, the larger view of movie remakes as metaphorically reflecting "the history and culture of this self-made and self-remade country" (330). But I wish to look into that area of cinematic remakes, mentioned above, that has received little critical scrutiny: what I call the cross-cultural makeover. If Hollywood is indeed the acknowledged dominant cinema in the world, the ways in which minority cultures appropriate and make use of that dominant discourse can prove instructive for both narrative film studies and cultural studies. Taken all together, this investigation should reinforce Victor Shklovsky's keen observation that "[i]n the history of art, the legacy is transmitted not from father to son, but from uncle to nephew" (49).

Narrative in any form is, as Edward Branigan reminds us, "[o]ne of the most important ways we perceive our environment" (1). But, as he also notes, narrative depends on building story structures "based on stories already told." In Branigan's useful analysis, narrative is studied both for the process of generating stories and for the act of comprehension. In either case there is the need for a level of experience that recognizes patterns of storytelling and thus the sense of a backlog of "stories already told" that are shared by storytellers (authors, filmmakers) and audiences. In most cases, of course, recognized patterns do not suggest a direct adaptation of a set tale but rather a range of similarities. In such a manner, we could, for instance, identify one kind of story "already told" as belonging to a "coming of age" pattern. As Branigan notes, "'[M]eaning' is said to exist when pattern is achieved" (14).

We recognize the remake as a more intensified and self-conscious form of the narrative process described by Branigan. Within the territory of the remake, "meaning" involves the knowledge of specific texts, not only for their patterns but for their characterization, tone, texture, and point of

view. Even more so than other forms of narrative, the remake announces itself as negotiating a self-conscious balancing act between the familiar and the new or the familiar "transformed."

Finally, what I will term the "makeover" is a particular form of remake that purposely sets out to make significant changes in what is either acknowledged or perceived as a prototype or important precursor to the film in question. Seymour Chatman has distinguished between overt and covert narration depending on the "degrees of audibility" of narrators (196). This distinction can also be applied to remakes. Films that clearly announce themselves as remakes in one or multiple ways are "overt" recastings, while the makeover is constructed to be more covert (by varying degree) in its audibility for the viewing audience. Makeover as a term will help us to emphasize the characteristics and strategies, overt and covert, of difference that the film in question presents in terms of previous texts while also noting possible levels of connection, similarity, continuity beyond various borders, geographic, intellectual, imaginative, and cinematic. Jean Renoir was fond of saying that he was not able to become a filmmaker until he realized his love for von Stroheim, Chaplin, Griffith, and Keaton had to be transformed into his own French "language," cinematic and linguistic, since he was, after all, French (Durgnat, 9).

Making over Narrative:

Family Business

At the core of the fabula, or story, of both Godfather films is what Coppola's characters call the twin peaks of their lives: the personal ("family") and "business." Building on Puzo's novel, Coppola managed to infuse the Hollywood gangster genre with a richly textured double dose of the Italian American immigrant experience in the United States and the importance of family life to that experience. As Peter Cowie has observed about the first part of the trilogy, "[T]he film is really a paean, not so much to the Mafia as to the pioneer spirit that enabled generations of Italians to sail to the USA, settle, and establish a new caste of ironclad proportions" (53). (See figure 22.)

Note to what degree Coppola's two films exist not as prototypes for Time of the Gypsies but as complex examples of stories "based on stories already told." On the most immediate level, The Godfather is an adaptation of the novel with the added connection that the script was written by the novel's author. And Godfather II thus appeared as a sequel. A further exploration, however, would have to discuss Coppola and Puzo's "rewriting" of the cinematic genre of the crime film. It is just as important to our understanding of Coppola's films to know what kind of border crossing Coppola has done between the various films that make up the genre of previous mob-crime

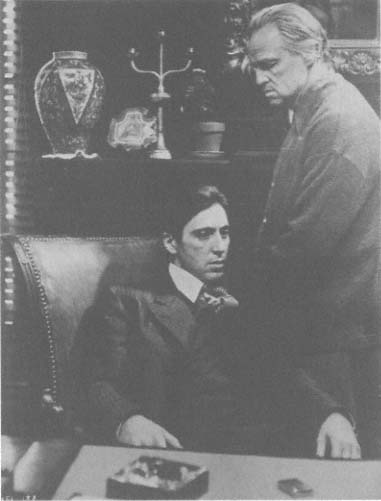

Figure 22.

The godfather, Marlon Brando (with Al Pacino), takes the role of

the gangster patriarch far beyond the genre stereotypes

of the past in The Godfather (1972).

films as it is to study the process of adaptation from Puzo's written page to Coppola's moving images. Noting such a complexity in speaking about Hollywood cinema, Raymond Bellour has observed that "in the classic American cinema, meaning is constituted by a correspondence in the balances achieved. . . . Multiple in both nature and extension, these cannot be reduced to any truly unitary structure or semantic relationship" (99).

Acknowledging such a pluralistic state of balances and meanings within

Figure 23.

A Balkan family portrait: Perhan (Davar Dujmovic), far right, standing

next to his beloved grandmother (Ljubica Adzovic), is the young Gypsy

who later becomes a gypsy Mafia member in Emir Kusturica's Time of the

Gypsies (1989), a makeover of Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather .

Coppola's texts as, to one degree or another, makeovers of previous crime films as well as adaptations of a novel, we can now turn to Time of the Gypsies and the even more complex nature of the makeover.

Kusturica's saga follows a similar story-subject perspective—that of business and family. Time of the Gypsies is an epic chronicle of a young Serbian gypsy, Perhan (Davor Dujmovic), from awkward adolescence through puberty, young love, travel, involvement in a godfather-controlled crime network in Italy, and on to his eventual marriage, fatherhood, godfatherhood, downfall, and death.[1] (See figure 23.) Perhan's struggle, like that of The Godfather 's Michael Corleone, is between his strong sense and need of family and the pressures on him to go into the "business," in this case a crime empire dedicated to selling gypsy babies and exploiting cripples, dwarfs, and women (via prostitution) across the border in Italy (all based on true accounts of over thirty thousand gypsy children "sold" into such slavery by their parents and other relatives, a practice that has not ended). Beyond these plot and thematic similarities to the Coppola films, the differences mushroom in the fertile soil suggested by The Godfather and Godfather II .

For our purposes, I shall focus on both the cinematic (including narrative) and cultural differences that Kusturica's text evokes, with the addition of an extra observation: Part of the pleasure of Coppola's trilogy is that of watching the high level of professional acting, in many cases by actors such as Marlon Brando and Al Pacino, who began their film careers with impressive stage backgrounds. Kusturica, in contrast, has gone in absolutely the opposite direction, using predominately nonprofessional gypsies to play themselves, though the roles of Perhan and Ahmed especially are played by well-known actors.

If we embrace the totality of difference served us by Kusturica and his screenwriter Goran Mihic,[2] we could describe the fabula-plot of this Balkan makeover in the following way: Time of the Gypsies is a dramatic-comic tale told with both realism and dreamlike fantasy, full of cinematic references, concerning an Eastern Orthodox Serbian orphan gypsy with certain telekinetic powers who is raised within a matriarchal culture by his grandmother. He becomes a gypsy godfather but ultimately fails to mature due to the lack of a proper father figure. He finally tries to resolve his personal crises by murdering his adopted "godfather"-father and is in turn murdered by the godfather's latest bride. His dying expression, however, is not one of pain but is instead a satisfied smile as he sees a vision floating above him suggesting his dead mother, wife, and beloved pet turkey. Rather than a sense of loss, Perhan's death has brought him a deeper peace and seeming understanding. On a deeply spiritual level, he has been fulfilled.

Let us now explore more closely the nature and implications of Kusturica's makeover, beginning with the level of the cinematic border crossing.

Making over Coppola's Godfathers

Style:

Gothic Realism vs Magic Realism

Coppola's style in the trilogy might be termed "gothic realism"—a blending of realistically based scenes shot in deep expressionistic tones and shades, with no flights of fantasy or dreams within the narrative. In strong contrast, Kusturica's film is, as I shall discuss more fully, dream oriented. Perhan's trickster figure Uncle Merdzan tells him at one point, "I see life as a mirage," and so do we for two hours as Kusturica treats us to frequent dream sequences and fantasy-like realities heavily influenced, according to Kusturica, by Gabriel García Márquez and the South American tradition of "magic realism."

The impermanence of gypsy life is more than one of physical mobility: it is a condition of the spirit, a perception of the universe, which Kusturica captures in his overall style and approach to his narrative. The gypsies, he told a New York Times interviewer, "move . . . easily from reality to illusion to

dream, as in a Gabriel García Márquez novel. Time of the Gypsies belongs entirely to the world of García Márquez and other Latin American writers who built their art on the irrationality and poverty of their people" (Insdorf). Thus, while a study of Coppola's films should, as we have noted earlier, incorporate a stylistic and narrative study of the American crime film genre, Kusturica's film could also be fruitfully studied in relation to the tradition of literary magic realism, suggesting once more the plurality of meanings Bellour alludes to in "reading" films.

Cinematic Tone:

The Tragic vs the Joyfully Comic

Coppola's vision, especially when taking the trilogy as a whole, is one of tragedy, of loss, of a falling apart as he himself has commented (Goodwin, 161–93). Kusturica's gypsy epic is one of what he calls "joy," a term that embraces "happiness and sorrow." This double vision is particularly reflected in the Charlie Chaplin motif worked throughout the film, including the final image of Uncle Merdzan, who has consciously acted out Chaplin for the amusement of the family earlier. We see him leave Perhan's funeral and run off through mud, wind, rain, his back to the camera, coat clutched, a cane in hand à la Chaplin. One could argue that Chaplin's solo endings in his films actually push us finally into melodrama rather than the comic. But the memories we have of Chaplin and of Kusturica's work is one tinged more with the comic than the tragic, though we are aware in both cases that the comic embraces pathos as well as laughter (Horton, Comedy/Cinema/Theory , 5).

Kusturica's Salute to World Cinema in an Age of Television

Coppola's Godfather films build on the whole American tradition of crime genre films. But Kusturica cuts a much larger territory of cinematic border crossing with direct and indirect references to over forty directors, ranging from the surrealism of Luis Buñuel to the straightforward, clean, narrative visual style of John Ford. Part of Kusturica's cinematic makeover strategy in Time of the Gypsy results in an anthology of allusions and homage to Yugoslav and European cinema, as well as to classical Hollywood movies. When Perhan becomes a godfather and dons the appropriate looking clothes, he winds up appearing remarkably like Al Pacino. At one moment, he stands in front of a movie theater playing Citizen Kane . As Perhan goes to light his cigar, he sees a still of Orson Welles with an unlit cigar in his mouth. Before lighting his own cigar, Perhan holds the match up to Orson Welles's Havana in a double allusion and tribute to Welles and, we can add, to François Truffaut, who staged a similar Wellesian homage in his first

feature, 400 Blows (1959), as well as in his later hymn to filmmaking itself, Day for Night (1973). Thus, while the overriding nod in The Time of the Gypsies is to Coppola's two films, Kusturica is at pains for us to understand that he is involved in a much larger cinematic world of influences and allusions.

It is significant that two of the most important European films of 1989 concern a double interest in the odyssey of young males trying to come of age and in the presentation of their narratives within a cinematic context that pays homage to, and asks for authentication from, a tradition of world cinema. I am speaking, of course, of Time of the Gypsies and the Italian-French Oscar-winning production of Giuseppe Tornatore's Cinema Paradiso . Like Perhan, the young boy in Cinema Paradiso must grow up without a father. But unlike his gypsy counterpart, the Italian boy has a grandfather figure in the character of a small town movie projectionist played by Philippe Noiret.

Even more striking, however, is the way in which both films embrace through allusions, film clips, and cinematic quotations their respective national film traditions and that of classical Hollywood and world cinema. Of course, in casting a narrative around, and in, a movie theater, Cinema Paradiso allows for a more overt dialogue on cinematic homage and a simultaneous need for authentication. But before discussing particular cinematic influences contained in Kusturica's makeover, we need to understand that both of these European films announce themselves as nontelevision at a time when television has not only supplanted cinema as the major entertainment form but has done so in an age when cinema has, in order to survive, in many ways become television. Kusturica wishes to celebrate particular masters of the cinema and their works—Yugoslav, Hollywood, and European—but he is also necessarily making it clear that he wishes to be authenticated and included in their company, in the family of national (Yugoslav) and world cinema.

The dilemma of world cinema today is well captured by Todd Gitlin when he notes: "More and more, movies themselves have turned into coming attractions—fodder for TV (and radio) morning shows, local and national TV news, syndicated shows like Entertainment Tonight, national magazines from People to Vanity Fair, USA Today and the newspaper style sections, novelizations, comic books, theme song records, toys, T-shirts, and, of course, sequels. The sum of the publicity takes up more cultural space than the movie itself" (15–16). Cinema Paradiso might more aptly be retitled Cinema Nostalgia , and Time of the Gypsies as Time of the Filmmaker as Gypsy . For in every way, Kusturica's film announces itself as a film and not as television. The allusions starting with Coppola and The Godfather are many, but 99 percent are to cinema and not the tube. And they may be called hymns to the movie-going cinema experience as well, for it is more than a sense of narrative closure that requires in Cinema Paradiso the blowing up of the

local cinema (and thus the main character's youth) to build a parking lot: a way of life has gone and the age of video and television has triumphed. Similarly, the very beginnings of love and sexual awakening take place in Kusturica's film as Perhan and Azra watch an important Yugoslav film (Rajko Grlic's The Melody Haunts My Memory [Samo Jednom Se Ljubi , 1980]) in a makeshift open-air cinema and try to imitate the passion on the screen while Perhan's pet turkey looks on.

Thus in our post-postmodern media times, when even American presidential candidates communicate with their audiences via television by mentioning television in the form of shows such as Murphy Brown, The Simpsons , and The Waltons , Kusturica places his Balkan-Hollywood film (produced and released through Columbia Pictures during the closing days of David Puttnam's reign) squarely within a realm of reference that champions the cinematic experience for filmmakers and viewers alike.

Within this context, Kusturica's vision is one that includes both a realist and a surrealist tradition: thus does John Ford meet up with Luis Buñuel within this gypsy cinematic caravan. These extreme borders go beyond individual filmmakers, of course, for to mention Ford and Buñuel is also to embrace the classical Hollywood tradition and the anarchistic European avant-garde at the same time.

Kusturica has often spoken of his love of Ford's films.[3] And there are many scenes in Kusturica's films that share a general set up of straightforward dramatic confrontation with simple camera work reminiscent of Ford's approach. Furthermore, there are direct allusions to Ford's work, as in the closing scene of Kusturica's first feature, Do You Remember Dolly Bell? (Sjecas Li Se Dolly Bell? 1981). In the final shot, a Bosnian family is loaded into an open truck with all of its belongings, and they begin to drive toward a new home. The direct reference to The Grapes of Wrath is not just cinematic but thematic as well: the family has suffered but will survive, despite all odds.