Streambank Stabilization Techniques Used by the Soil Conservation Service in California[1]

David W. Patterson, Clarence U. Finch, and Glenn I. Wilcox[2]

Abstract.—Streambank protection techniques used by the USDA Soil Conservation Service (SCS) have evolved over many years of experience. Structural and vegetative protection measures are generally used in combination. SCS designs are based on national standards promoting protection measures which are sound from environmental, economic, and engineering perspectives. The general principles for planning streambank protection measures are presented as well as brief descriptions and typical costs of several structural and vegetative methods.

Introduction

Streambank protection techniques are technical conservation practices requiring the combined planning efforts of engineers, biologists, plant material specialists, and agronomists. The USDA Soil Conservation Service (SCS) provides technical assistance through local resource conservation districts for the planning and design of streambank stabilization systems on America's smaller streams and rivers. It is fair to say that the techniques SCS now uses for protecting and revegetating streambanks have evolved over many years of trial, error, and success.

The response of resource agencies and the public to streambank protection projects has often been emotional. However, those who have closely evaluated SCS work are gaining confidence in our approaches to streambank protection. In several instances representatives from the USDI Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) have used SCS methods for placement of natural rock riprap and reestablishment of vegetation as examples for streambank protection methods.

SCS is aware of its responsibility to design conservation practices which are sound from both environmental and engineering perspectives. Toward that end SCS has developed designs and techniques which serve as standards for streambank protection work.

Resources Worth Protecting

Throughout this conference a great deal of time and effort will be rightfully expended extolling the many inherent values of riparian systems. However, often overlooked, taken for granted, or at least underemphasized, is the value of soils and other substrates within riparian systems. Soils and other substrates located within and adjacent to water bodies and waterways provide the substrates on which riparian vegetation grows. In addition, deep alluvial soils of high agricultural value are often found within and immediately adjacent to riparian zones.

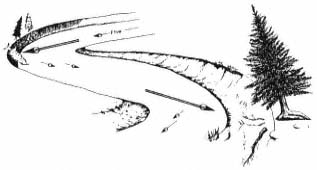

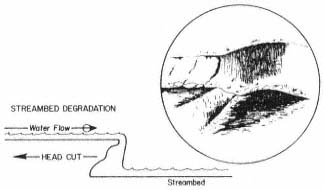

The erosion of riparian soils and substrates acts as a double-bitted axe. Erosion within riparian systems not only permanently removes productive soils and substrates and associated vegetation, but also results in a reduction in downstream water quality (fig. 1). Streambank erosion and associated stream meander and soil loss are unacceptable to most private landowners, especially for owners of high-value specialty crops such as grapes, as well as in urban areas. Streambank erosion and meander within private lands can result in the loss of highly productive and valuable agricultural soils, loss of or damage to expensive irrigation systems, levee failure, loss of real property, desiccation of meadows, and loss of riparian vegetation (fig. 2). Head cutting (fig. 3) in streams and gullies is another major source of erosion and sedimentation, leaving scars on the face of the earth that are difficult and expensive to heal.

[1] Paper presented at the California Riparian Systems Conference. [University of California, Davis, September 17–19, 1981].

[2] David W. Patterson is Biologist, Red Bluff, California; Clarence U. Finch is Agronomist, Fresno, California; Glenn I. Wilcox is Biologist, Salinas, California; all are with the USDA Soil Conservation Service.

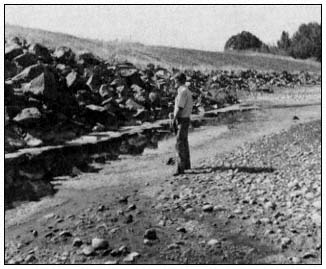

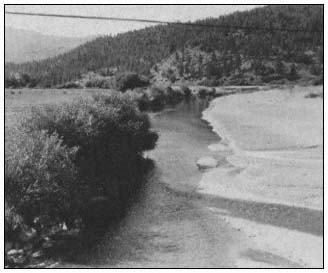

Figure 1.

Streambank erosion results in the loss of streamside

soils, substrates, and associated riparian vegetation,

which enter the waterway, resulting in siltation

and reductions in downstream water quality.

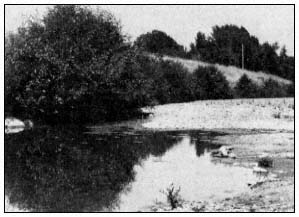

Figure 2.

Active streambank erosion destroys valuable riparian vegetation.

Figure 3.

Head cutting and streambed degradation are major causes

of erosion and streambank sloughing in waterways.

Some General Principles

SCS recognizes and supports the need for proper land-use planning on land areas containing waterways. This is especially important in areas where inadequate planning has allowed urbanization up to the edges of eroding and meandering streams. SCS also encourages the practice of setbacks and appropriate use where agricultural lands contain or are traversed by riparian systems.

Several principles are observed by SCS in the design of streambank protection systems. Channelization of waterways must be avoided, otherwise upstream repairs may create new problems downstream. As an example, adequate natural meander must remain to dissipate flow energy (fig. 4 and 5). Protection work must be carefully planned to avoid removing or damaging any more vegetation than is absolutely necessary. It is especially important to determine if apparent streambank erosion is actually a symptom of streambank degradation. Streambank protection efforts are doomed to failure if streambed degradation and undermining are creating evermore critical angles of repose on associated streambanks (fig. 6).

Figure 4.

Stream meanders dissipate flow energy naturally.

Figure 5.

Streambank protection measures for outside curves

must retain adequate meander for energy dissipation.

The environmental attributes of streambank protection projects must be acceptable in the long-term. Too often people judge the environmental acceptability of projects immediately upon their completion. The streambank shown in figure 7 appears to be aesthetically undesirable, but protection measures were completed just before the photograph was taken. Figure 8 shows the same project five years later. In most cases it is five years before shrub and tree plantings achieve enough growth to reflect the total planning effort put into a typical project. It is important to keep this longer-term time frame in

Figure 6.

The forces of streamflow and abrasion combined

with streambed degradation and gravity are

the key causes of streambank erosion.

Figure 7.

A riprapped outside curve on Anderson Creek,

Mendocino County, just after construction was completed.

Figure 8.

The same riprapped outside curve on Anderson

Creek, Mendocino County, five growing seasons

after construction. Willow and alder are becoming

well established. Before the project the streambank

was a 3- to 6-m. (10- to 20-ft.) tall 90º cutbank

threatening a schoolyard.

mind when commenting on proposed and newly completed projects.

SCS does not recommend the use of either car bodies or concrete slabs for streambank protection. Uncompressed car bodies are unsightly and unsound from an engineering standpoint. Concrete slabs are unsightly, often lack adequate density, and, because of the typical flat configuration of the material, are subject to tumbling in high flows.

SCS and landowners consider opportunities to create or re-create fish habitat. On many projects summer habitats for both game and nongame fish are actually improved over preproject conditions. Large riprap rocks which fall to the stream bottom during construction are generally left where they fall near the toe of the bank. Water working around the instream rock, and between the rock and the armored bank, creates pools which, when combined with reestablished overhanging vegetation, provide quality summer habitat. In comparison, "naturally eroding" 90° cutbanks not only have little to offer, but serve as sources of downstream pollution and sedimentation (fig. 9).

Figure 9.

Streambank erosion is a major factor in the

loss of riparian vegetation and substrates, as

well as sedimentation and water pollution.

Design and Planning Considerations

During project planning SCS engineers and planners consult SCS biologists and invite input from other agencies including the California Department of Fish and Game (DFG) and FWS. Cooperation during planning and design is now required under formal Channel Modification Guidelines (USDI Fish and Wildlife Service and USDA Forest Service 1978) which were jointly written by SCS and FWS. SCS conducts formal environmental evaluations for all streambank protection projects for which it provides designs. Both DFG and FWS are asked to participate in the evaluation process.

Landowners requesting SCS project designs are required to obtain all necessary permits before starting construction. Streambank protection work is carried out by cooperators during lowest flow periods or in dry streambeds when conditions for construction are best and the potential for downstream pollution is the lowest.

Streambank protection designs are normally limited to armoring outside curves, protecting instream structures, and protecting straighter reaches where loss of streamside resources is unacceptable. All designs must comply with appropriate SCS, state, and national conservation practice standards and specifications.

These design standards and specifications include:

1) channel vegetation;

2) critical area planting;

3) grade stabilization structure;

4) stream channel stabilization;

5) open channel;

6) streambank protection;

7) sediment basin.

Design criteria are also drawn from SCS engineering handbooks, engineering field manual, field office technical guides, and other technical resource material.

Streambank Protection Techniques

Although most often used in combination, SCS streambank protection techniques can be divided into two types: a) physical protection; and b) vegetative protection.

Physical Protection Techniques

Grade Stabilization

A dam, wall, or drop is used to reestablish or maintain streambed elevation (fig. 10). Maintenance of streambed elevation is necessary in stabilizing streambanks. Environmental considerations in designing grade stabilization measures include choice of construction materials, fish passage, plunge pools, number of structures used and their locations, and incorporation of vegetation.

Figure 10.

Grade stabilization structures used to either maintain existing grade or raise streambottom by trapping sediment.

Rock Riprap

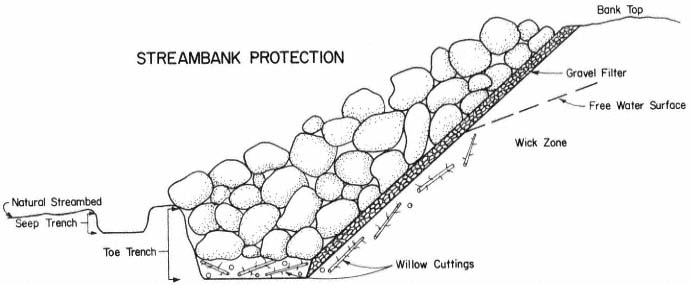

Natural rock of appropriate size, density, and gradation is placed on shaped streambanks and in open-toe trenches. A gravel filter is placed under the rock to prevent erosion of soil material from beneath (fig. 11). Extensively eroded outside curves are generally realigned with enough "bend" left for necessary energy dissipation. Environmental considerations include impacts at sites where rock is obtained; preservation of as much existing streamside vegetation as possible during construction; construction during low-flow or dry stream conditions; preservation or enhancement of fish and wildlife habitat; fencing; and seep trenches. Stabilization of streambed grade may be an integral part of this measure.

Concrete grout may be incorporated where channel alignment problems and/or flow velocities require greater protection from the influence of scouring or high-energy flows. Environmental considerations include the use of vegetation,

Figure 11.

A typical streambank in cross section protected with natural rock over gravel bedding and willow cuttings.

The toe trench is used to trap bank seepage and encourage better growth of cuttings and natural vegetation.

visual impacts, aquatic life, and use of colored grout.

Post-and-Wire Revetment

Wire mesh strung on four-inch steel diameter or wooden posts, braced with steel cables along the top and bottom edges of the wire mesh, are used where flow, abrasion, and instream debris conditions will allow. Post-and-wire revetments are commonly used where rock is unavailable or not cost-effective in comparison. Riparian plantings immediately behind wire revetments are an integral part of revetment establishment and maintenance.

Figure 12.

A typical rail-and-cable revetment located

on Rancharia Creek in Mendocino county.

Rail-and-Cable Revetment

Rail-and-cable revetments (fig. 12) are similar in general appearance and function to post-and-wire revetments but are usually taller and made of heavier material to withstand greater water velocity, more abrasion, and debris problems. The revetment is covered with wire mesh with cables strung along the bottom, middle and top of the revetment. Riparian plantings are important components of rail-and-cable revetments.

Rock-and-Wire Revetment

Rock-and-wire revetments are essentially a well-braced double post-and-wire revetment with rock or very coarse gravel placed between the revetment walls. Riparian plantings are an important component of this type of revetment. Although they are expensive, properly located and constructed rock-and-wire revetments are quite stable as long as the wire withstands abrasion.

Pilot Channels

Pilot channels are dug in streambed material and used to "train" water away from newly treated streambanks, keep water out of construction areas, and increase chances of establishing newly planted vegetation.

Gabion Baskets

Gabion baskets are rectangular, heavy-mesh wire baskets filled with coarse gravel, which are placed and then wired together in series. Gravel size must be large enough to prevent leakage through basket mesh. Abrasion may break the wire mesh, requiring periodic maintenance. Gabions are used where large rock is unavailable or not

cost-effective. Plant material, generally in the form of willow cuttings, should be placed under, behind, and within baskets where moisture is adequate for growth.

Jacks and Cabled Trees

Past experience has shown these two methods to be less effective than many other methods. Cabled trees may be considered where ample trees are available and cost of other methods is absolutely prohibitive.

Vegetative Protection Techniques

Woody Cuttings

Cuttings are taken from locally adapted and locally growing plants when possible. Species which have been used include willow (Salix spp.), athel (Tamarixaphylla ), and tamarisk or salt cedar (Tamarixgallica ). Methods and procedures for taking and planting cuttings are provided in construction plans and specifications written for each project. In general, cuttings are laid horizontally in open-toe trenches and on shaped banks, as shown in figure 13, or planted vertically. If natural moisture is inadequate for growth, irrigation must be provided to insure establishment. Vertical plantings should be placed at a minimum depth of 1 m. (3 ft.) with 0.3 m. (1 ft.) of the cutting extending above the ground. The growing tip must extend aboveground. The best results have been obtained by augering holes for cuttings and watering cuttings in by washing soil material in around them. Watering in insures that cuttings are completely surrounded by soil which is devoid of air spaces. Immediate and generous irrigation should be provided at the time of planting. Water jetting can be used to both dig holes and water in plants where adequate water supply and pressure are available and soil texture allows.

Figure 13.

Placement of willow cuttings on bottom of toe trench and on moist areas (wick zone) of sloped banks.

Rooted Woody Plants

Rooted woody plantings are made on the bank side of revetments or on levees or streambanks above bank protection materials. Rooted plants can also be placed in planters set in concrete or gunnited rock. Unless natural seepage is adequate, plantings must be irrigated for at least two or three years for establishment. Plant species selection is influenced primarily by site conditions, soils, climate, plant availability, price, and wildlife habitat needs. Mulching is strongly recommended around and between plants. Herbaceous plants can be used in combination with rooted woody plants but should not create competition for the woody plants.

Herbaceous Plants

Perennial and annual grasses and forbs are seeded on sloping banks where mineral soil is exposed and on any disturbed areas on top of banks. Species selection, site preparation, timing, and seeding are all critical elements. If planted in combination with rooted woody plants, herbaceous seedings should be kept several feet away from establishing woody plants to avoid competition for space, moisture, and nutrients.

Mulching

Mulching around woody plants and over seedlings with straw and erosion control blankets

made of jute, fiberglass, wood fiber, and other materials is recommended on steep and erosive streambanks and levees. Straw should not be chopped in lengths shorter than 15 cm. (6 in.) and should be anchored either mechanically or with fiber mulch and a tackifier. Fiber mulch should be wood cellulose fiber containing no germination- or growth-inhibiting properties. Fiber mulch should be hydromulched as a slurry containing tackifier at a rate of 1,500 pounds per acre. Seed can be either mixed with the slurry or the fiber slurry applied over the seeded area.

Costs

Location, situation, type of contract, contractor, and project size greaty influence the price paid for a particular job. The price ranges of some common streambank protection methods are given below. When used in combination, the costs of each operation or structure type must be added together. Maintenance costs must also be taken into consideration.

Dumped rock (quarry run)—$20.00 or more per foot.

Livestock fence revetment (metal fence posts with braces and hogwire)—$0.40 to $0.60 per foot.

Four-inch by four-inch treated wood fence post-and-wire mesh revetment with braces—$12.00 to $15.00 per foot.

Four-inch double steel pipe, wire, and rock revetment with braces and ties—$15.00 to $30.00 per foot.

Rail-and-cable revetment (9-pound rail and one-inch or larger cable)—$30.00 per foot.

Combination seed, fertilizer, and mulch—$600.00 to 1,000.00 per acre with higher costs for smaller areas.

Planted woody cuttings—a) watered in—$2.00 to $3.00 per cutting; b) jammed in—$0.50 to $1.00 per cutting.

Planting one-year-old rooted woody plants—$2,400.00 to $2,700.00 per acre (includes materials).

Streambank protection projects are expensive in terms of dollars spent. Furthermore, riparian resources provide few direct benefits to private landowners relative to the cost of protecting and maintaining the resource. The conservation of streamside soils must be viewed as a long-term investment for the good of future generations. Values such as natural beauty, fish and wildlife habitat, and water quality enhancement directly benefit the public in both the short and long term. For this reason, the financial participapation of the public in riparian conservation programs is strongly encouraged. In the Scott Valley alone since 1968, over $1 million has been spent protecting streambanks along the Scott River. Approximately 70% of the cost has been provided by cost-shares under the USDA Agricultural Conservation Program (ACP). Much more work and much more cost-sharing are needed on the Scott River and throughout the state and nation.

Conclusion

For years SCS seemed to wear, and to some degree deserved, a black hat when it came to "doing its thing" in streams and waterways. Things have changed for a number of reasons. SCS has, through experience, learned some lessons and developed creative and feasible methods of streambank protection and conservation of riparian systems. Figure 14 shows an example of quality streambank protection work utilizing natural rock riprap designed by SCS. After 13 years the project is nearly mature, providing quality habitat. A woman who passes this site every day reported that she could not believe the riverbank had been shaped and riprapped. The SCS standards and specifications and other technical materials are available at local, area, and state SCS offices. Public participation in planning and evaluating streambank protection systems is always invited.

Figure 14.

A fully mature project creating quality terrestrial

and aquatic habitat, as well as providing strong

visual appeal. It takes time and money.

Literature Cited

USDI Fish and Wildlife Service and USDA Soil Conservation Service. 1978. Channel modification guidelines. 15 p. Limited publication for agency use. Washington, D.C.