Reproduction as Speculation: Drawing on Chance

No stars? chance annulled?

—Stéphane Mallarmé, Igitur

You see I haven't quit being a painter, now I'am drawing on chance.

—Marcel Duchamp

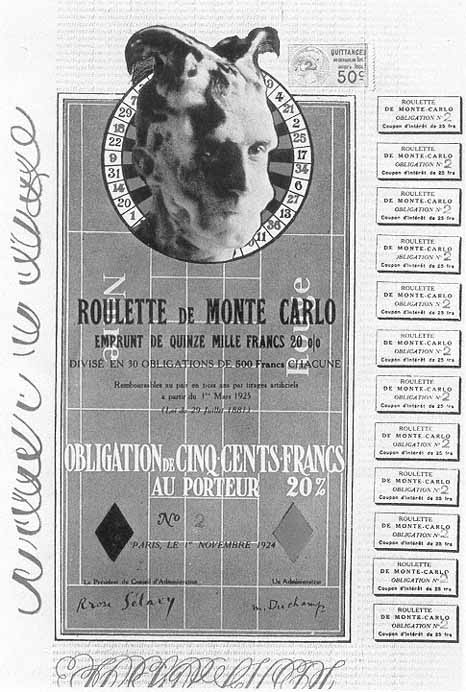

In the Monte Carlo Bond (fig. 63), a work immediately following Wanted/$2000 Reward, Duchamp explicitly pursues the analogy between art and gambling. In addition to the financial implications of this work, the Monte Carlo Bond may be considered an effort on Duchamp's part to put up a bond for himself, as security for another, in order to bail himself out of jail. Presumably, this is a response to his self-identification as an artist/gambler and his identification of art as a scam in Wanted/$2000 Reward. The problem, however, is that Duchamp appears to be issuing a bond on his own authority, responding to the initial scam staged by Wanted, through the introduction of an even more elaborate scam. A bond is an interest-bearing certificate issued by a government or a corporation to pay a principal sum on a certain date, with interest. The Monte Carlo Bond (issued as a limited edition of thirty copies) was to be sold at Fr 500 with a guarantee of 20 percent interest redeemable in three years by "artificial drawing of lots" (Remboursable au pair en trois ans par tirages artificiels), starting 1 March 1925. The appearance of this fictitious bond immediately undermines the authority of the financial transaction it is intended to secure. The Monte Carlo Bond is a collage (an "Imitated Rectified Ready-made") of a color lithograph of a roulette table with Man Ray's photo of Duchamp's soap-covered face and head, glued to a roulette wheel. Parodying an official financial document, this bond bears all the marks of "authenticity" associated with this type of transaction. It is an individually numbered bond, signed twice by Duchamp, on the right as Rrose Sélavy (president of the company), a "name by which Marcel is as well-known as his regular name" (WMD, 185), and on the left as Marcel Duchamp (an administrator). As Amelia Jones observes, Duchamp's double signature as himself and as Rrose Sélavy, suggests that

Fig. 63.

Marcel Duchamp, Monte Carlo Bond (Obligations Pour La Roulette De Monte Carlo),

1924. Imitated rectified ready-made: collage of color lithograph with photograph by Man

Ray of Marcel Duchamp's soap-covered head.

Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Rrose is an independent partner, one who, as president, presumably has authority over Duchamp, who is a mere administrator: "Rrose becomes an author through signing and yet she herself has been 'authored'."[32] Duchamp's game with his own authorial persona, Rrose Sélavy, legitimizes the bond through the production of a corporate entity whose composite identity is generated by the fiction of his alias, of himself as an other. The collective signatures designating the corporate identity embodied in the bond, which both authenticate and authorize it, here emerge as the punning mirrors of Duchamp's literal embodiment as a corporation. By problematizing his own authority as an artist, through the fictional inscription of an other (be it Rrose, his female counterpart, or the spectator who "makes the picture"), Duchamp reveals the tenuous bond between the author and the work, especially when the work functions as a putative embodiment of the artist.

Duchamp's photograph on the Monte Carlo Bond, a self-portrait of his head covered with shaving foam and his hair pulled up into horns, further destabilizes the authority of this financial document. The fact that this bond is framed by the uninterrupted phrase "Moustiquesdomestiquesdemistock" (domestic mosquitos half-stock), only adds evidence that the visual appearance of this work might be as unreliable as the signatures backing it up. While Duchamp's appearance, his readiness for a "shave," might be interpreted psychoanalytically as a sign of decapitation or castration, such a premise fails to take into account the fact that the context of this bond involves gambling.[33]

Could Duchamp's ready-to-be-shaved head be the Joker, that extra card used in certain card games as the highest trump, or in another context the nullifying clause of a legislative measure? What kind of concealed obstruction or difficulty does this image represent, and is the threat of this close shave the sign of a narrow escape? The clue to this image, as in most of Duchamp's works, lies not merely in its visual referent, but in its discursive one as well. To shave means to fleece or cheat, to drive a hard bargain, and in commercial slang it means to buy notes or securities at a discount greater than the legal rate. Is Duchamp's impending "shave" intended to take a barb at the spectator—a pointed joke on himself and others? Having "shaved" the Mona Lisa by taking a reproduction that has not been altered by his graffiti mustache and goatee, Duchamp

"spends" this image by putting it into circulation under his own signature. By reinvesting this reproduction with a new kind of "interest," in effect, he "banks" on it, thereby reducing it to a financial issue, a "bond" of sorts. Duchamp and Leonardo become the corporate backers of this reproduction, which now attains an "original" status.

Likewise, in the case of the Monte Carlo Bond, Duchamp's hint at "shaving" himself suggests a clue as to how he might be "shaving" (cheating or fleecing) the spectator. The threat of his impending "shave" implies restoring his own image to its female counterpart, Rrose Sélavy. This act of restoration, however, does not lead to the uncovering of an original but that of an alias (a reproduction), whose financial authority is backed by the fictitious corporate identity of Duchamp/Rrose Sélavy. Duchamp's calling card (and perhaps his business card, as well) introduces him as "PRECISION OCULISM/ RROSE SÉLAVY/ New York-Paris/ COMPLETE LINE OF WHISKWERS AND KICKS" (Oculisme de Précision/ Poils et Coups de Pieds en Tous Genres ). This dual specialty in precision oculism and whiskers and kicks further emphasizes Duchamp's particular expertise as an artist whose business is visual and linguistic puns. Oculiste sounds like (au culiste, meaning "in the ass" in French), yet another allusion to Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q., thereby attesting to Rrose's specialization in precision ass and glass work. Whiskers and kicks refer to Duchamp's pointed barbs at tradition, his travesties of the Mona Lisa "shaved" and "unshaved." As Michel Sanouillet and Elmer Peterson point out, "Duchamp hardly ever misses a chance to boot us in the rear when we are reverently bent over examining and explicating his work" (DMD , 105).

Rather than identifying its carrier, this calling card thus establishes Duchamp's particular intervention as an artist of multiple embodiments: his interrogation of the visual (ocular) invariably sets the spectator into motion by forcing him/her to stumble through puns. Robert Lebel points out that Duchamp "cheerfully masqueraded as an American style 'businessman'." He participated in the management of a cleaning and dyeing establishment, simply because it allowed him to designate himself as a "tinter" (a pun on peintre [painter] and teinturier [dyer]).[34] Thus, while it may seem that Duchamp is abandoning art when he turns to issuing bonds, this gesture emerges as yet another attempt to rethink art in speculative terms.

The public reception of Duchamp's bond verifies the speculative conflation of the artistic and the economic. Duchamp's issue of the Monte Carlo Bond was immediately valued not for its financial interest but as an artistic investment. In The Little Review (New York, Fall-Winter, 1924-25) we find an account of the public's reaction to this work:

If anyone is in the business of buying art curiosities as an investment, here is a chance to invest in the perfect masterpiece. Marcel's signature alone is worth much more than the 500 francs asked for the share. Marcel has given up painting entirely and has devoted most of his time to chess in the last few years. He will go to Monte Carlo early in January to begin the operation of his new company. (WMD, 185)

This account of Duchamp's work indicates that the "interest" of the public is not focused on the "interest" bearing possibilities of the bond but rather on the value of this work as an art investment, guaranteed by Duchamp's signature. Given the fact that Duchamp "gave up" painting, buying a bond assures getting a "masterpiece," since the artistic value of this limited edition work is guaranteed to exceed its actual value as a financial investment. The interest bearing value of this work as art exceeds its reality as financial security by invoking contingencies that extend beyond the authority and life of the artist into the speculative futures of posterity.

In order to illuminate the artistic implications of the Monte Carlo Bond it is important to consider Duchamp's letter to Jean Crotti (17 August 1952). In this letter Duchamp explains that artists are like gamblers, and that their reputation is made by the chance encounter of the work with the spectator:

Artists throughout history are like gamblers in Monte Carlo and in the blind lottery some are picked out while others are ruined. . . . It all happens according to random chance. Artists who during their lifetime manage to get their stuff noticed are excellent travelling salesmen, but that does not guarantee a thing as far as the immortality of their work is concerned.[35]

By identifying artists with gamblers in a blind lottery, Duchamp underlines the arbitrary way in which value is generated by the artwork. The successful artists are like traveling salesmen, able to capitalize on their chance encounters with the spectator, in order to valorize their work. By defining the viewer as someone who "makes the picture" alongside with the artist, Duchamp inscribes the work within a circuit of symbolic exchange. The artwork is thus redefined: it is neither an independent object nor does it belong to the author any more than the viewer. The artistic value of the work cannot be isolated from its social context: its display, consumption, and circulation. This is why "Posterity is a form of the spectator" (DMD , 76).

This redefinition of the artistic process as a gamble, which relies on the regard, or rather, "interest" of the spectator, leads to a radical challenge of the autonomy of painting as a discipline. As Duchamp explains to Crotti: "I don't believe in painting itself. Painting is made not by the painter but by those who look at it and accord it their favors; in other words, there is no painter who knows himself or is aware of what he is doing."[36] The authority of painting is fractured by the fact that the artist alone cannot confer value on a work. The appeal to the tradition, to those works whose value is ensured by the museum, is unreliable to the extent that the exhibition value of the work depends on institutional considerations. A last resort to individual judgment is also doomed to failure, since neither self-knowledge nor self-discipline can guarantee the future "interest" of the work. As Duchamp points out to Crotti, "don't judge your own work, since you are the last person to see it truly (avec des vrais yeux ). What you see is not what makes it praiseworthy or unpraiseworthy."[37] The individual judgment of the artist is shaped by the authority of one's education or one's reaction against it. Thus the effort to evaluate the work reveals the artist's subjective limits, the extent to which they are arbitrarily mediated by institutional givens.

Duchamp's refusal of aestheticism, the belief in painting for its own sake, is visible in Duchamp's earliest attempts to move away from painting and toward mechanical drawing and experiments with chance operations. The Monte Carlo Bond is issued in order to test a formula for turning the odds at roulette in the player's favor by "pitting the logic of chess against the luck of the gaming tables."[38] This work may be considered as

yet another instance of Duchamp's efforts to "can chance," as in Three Standard Stoppages and Dust Breeding (the photograph of dust in the region of the Sieves on the Large Glass ). The Monte Carlo Bond represents a deliberate effort to examine the speculative gamble entailed by both financial and artistic endeavors.[39] If the logic of chess is invoked in the context of this financial and artistic parody, this is by no means accidental, given the punning relation of chess (jeu d'échecs ) to checks (jeu des chéques ).[40]

How can the "logic" of chess be pitted against the "luck" of the roulette table? As we have shown earlier, Duchamp sees chess as a "visual and plastic thing," that is, not purely geometric, since it moves—"it's a drawing, it's a mechanical reality" (DMD , 18). According to Duchamp, playing a game of chess is "like designing something or constructing a mechanism of some kind by which you win or lose" (WMD , 136). In chess this mechanism is constituted by a strategy (a set of moves or decisions) of two opponents, who, in order to play, must literally put their "heads together." The case of roulette, however, is closer, as Hubert Damisch notes, to a head or tails game.[41] Yet roulette is more than a game of chance, since at each moment the player must decide on a number and a color.[42] But despite its arbitrary character, betting is often handled like chess, through predetermined strategies attempting to contain the chance element through the number of moves.[43]

The Monte Carlo Bond is issued by Duchamp to raise funds for a betting system for the roulette, which Duchamp describes as follows:

It's delicious monotony without the least emotion. The problem consists in finding the red and black figure to set against the roulette. . . . The Martingale is without importance. They are all either completely good or completely bad. But with the right number even a bad Martingale can work and I think I've found the right number. You see I haven't quit being a painter, now I'm drawing on chance . (WMD , 187; emphasis added)[44]

Duchamp's attempts literally to "draw on chance" (dessiner sur le hasard ) can be understood as an effort to recognize its plastic character by outlining its mechanism through a number of moves, thus, containing

it through a calculus of probability.[45] Rather than functioning as an invocation of pure contingency, chance, for Duchamp, is contextually defined, like value. Betting strategies have no meaning in and of themselves; they are indifferent. What matters, on the contrary, is the fact that these betting mechanisms contextualize chance, by literally "drawing" it in. The monotony of repeating a set of moves, with very small variations, uncovers the strategic and transitory outline of chance, an imprint of its fugitive passage.

Duchamp's financial gambit stages his artistic gamble as an artist whose reputation is, like life itself, "on credit." If art is a blind gamble, then the Monte Carlo Bond represents the obligation: it is a guaranteed interest-bearing certificate. As a speculative financial instrument, this bond provides the strategic mechanism for addressing the question of "interest" art. As Duchamp explains in a letter to Jacques Doucet (Paris, 16 January 1925): "Don't be too skeptical, since this time I believe I have eliminated the word chance. I would like to force the roulette to become a game of chess. A claim and its consequences: but I would like so much to pay my dividends" (WMD , 187–88). Duchamp's belief to have eliminated chance corresponds to his efforts to "can chance" (hasard en conserve ), by conserving or containing it. Duchamp's gesture emerges as a challenge to Stéphane Mallarmé's statement that "a throw of dice will never abolish chance." At issue for Duchamp is not the abolition of chance (which has little meaning) but rather, the effort to foil it by "canning" it, that is, preserving it as a strategic gesture particular to a set of determinations. Thus Duchamp's "canning" is also another way of "drawing" (dessiner ) on chance, like drawing checks (or drafts) on a bank. The Monte Carlo Bond enacts, in its "interest" generating potential as a financial document, the gamble that the artist is engaged in, in terms both of the artistic medium, and of the history and traditions that validate the work. If Duchamp is able to issue bonds as a way of securing and guaranteeing dividends on his "interest," this is because while art may be a gamble, the contextual logic of its operations is like a chess game. If we recall Duchamp's advice to John Cage, "Don't just play your side of the game, play both sides," we begin to see that Duchamp's success in "drawing on chance" is the result of playing the game of art from both sides, interchangeably and simultaneously as artist and spectator.[46]

Fig. 64.

Marcel Duchamp, Drain Stopper (Bouche-Evier), 1964 (obverse/reverse). Bronze.

Courtesy of The Philadelphia Museum of Art, Louise and Walter Arensberg Collection.