Chapter 3—

Petrarchizing the Patron—

Vernacular Dialogics and Print Technology

Although the manoeuvres of Florentine patronage remain largely hidden, we have seen that the patrons' personalities and social identities do not. By comparison, the identities of non-Florentine patrons of music in Venice, even noble ones, are obscure at best. These figures had nothing of the ultra-high society and finance or international politics to compare with the likes of Strozzi and Capponi. Official historians and heads of state were generally unconcerned with their business and their movements; nor as a rule did hired secretaries or agents keep track of their more sedentary and prosaic lives. By contrast with literary patrons like Domenico Venier, whose constant verbalizing yields a portrait rich in tone if not always in specifics, the doyens of musical patronage kept relatively quiet. Figures interested in music often fell outside the regular patterns of verbal exchange that would have chronicled their lives for future generations. In musical realms it is largely composers themselves and their professional ghost writers, surrogates, or publishers who shed light on musical benefactors, mostly in the conventional form of dedications, sometimes in the less direct and often less intelligible form of dedicatory settings. Only the unprecedented fusion of Venetian literary and musical activities during the 1540s helps expose Venice's non-Florentine musical patrons to our distanced view. In the dialogical bustle that Venetian Petrarchism produced, musical patrons increasingly placed themselves — or were placed by acquaintances — squarely amid the verbal transactions that were the more common preserve of literati. It is this phenomenon that unlocks otherwise sealed doors. To open them I begin with some connections between the business of printing and the business of writing.

In sixteenth-century Venice texts became a major commodity. The local presses that had specialized in meticulous limited editions early in the century were gradually supplanted for the most part by firms that produced a huge number of volumes at great speed. As presses cranked up production, words came to be marketed in a

range of forms and sheer quantity that were new to the modern world. Print commerce boomed, moreover, as part of a clamorous urge to engage others in dialogue. A remarkable number of texts issued in the mid-sixteenth century utilized some mode of direct address or concrete reference, or concocted a world of imaginary interlocutors.

By the middle of the century these dual phenomena — the urge to dialogue and the quest for diversity — had brought more authors, more vernaculars, and more literary forms into the hurried arena of published exchange than had ever been there before. Composers and patrons numbered among the many groups who were drawn into increasingly public relationships as a result. For them (as for people of letters), the new public nature of verbal interchange could prove by turns threatening and expedient. On the one hand, it exposed private affairs — or fictitious imitations of them — to social inspection and thus caused tensions over the commodification of what was individual and supposedly personal. On the other hand, it allowed its ablest practitioners to manipulate their social situations, reshape their identities, and, in the most inventive cases, mobilize their own professional rise.

All of this occurred not simply because the quantity of publications had increased but because new mechanisms of literary exchange were encouraged by the vernacular press. These mechanisms took the form of what I will call "dialogic genres." I coin this term principally to interrelate the great variety of writings that fashioned transactions in the form of letters, poetic addresses, and counteraddresses, that fictionalized the interchanges of salons, academies, and schoolrooms, or constructed discourses of address in dedications, dedicatory prefaces, letters, and occasional or encomiastic poems. All of these modes involved speaking to and among others — to patrons, lovers, enemies, and comrades; among teachers and students, scholars and mentors, authors and patrons, courtesans and clients.

In this sense my appeal to the concept of a literary dialogics, however difficult to define, is historically grounded in sixteenth-century Venice, and particularly in the multiplicity of new literary forms linked to an active print commerce. But I also mean for it to resonate with something of the same multivocal plurality with which the Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin characterized the nineteenth-century novel.[1] Language, for Bakhtin, was continually stratified into social "dialects" by the centrifugal forces of social use. Dispersive and fragmenting, those forces prevented languages from maintaining the sort of uniform character that official doctrines might try to prescribe and perpetuate for them. As part of living acts, language is instead seen to thrive in the face of potential contestations that always reside

[1] Bakhtin's theories were worked out in a great many texts, most importantly "Discourse in the Novel," written in 1934-35; see The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist, trans. Michael Holquist and Caryl Emerson (Austin, 1981), pp. 259-422. Useful introductions to Bakhtin's notion of dialogism and his specialized vocabulary may be found in the Introduction and Glossary of that volume and in Tzvetan Todorov, Mikhail Bakhtin: The Dialogical Principle, trans. Wlad Godzich (Minneapolis, 1984).

somewhere between immediate uses and other possible uses. Language always asserts itself against the alien terrain of a listener — or in one of Bakhtin's most famous phrases, it "lies between oneself and another."

For Bakhtin this aspect of language was basic to its status as communication, written or verbal. Yet he argued that not all genres foreground this pervasive condition of language at their stylistic surface. As Bakhtin saw it, while novels were explicitly dialogical, poetry — by claiming to spring from a single authorial voice — pretended to a monological status, albeit one he believed was always ultimately fictitious. We could extend Bakhtin's dichotomy so as to place early modern dialogues, letters, encomia, and dedications on the dialogic side and genres like treatises and theses on the fictively monologic. What I call "dialogic genres" mark out an early modern instance of the general linguistic condition Bakhtin called "dialogism." Indeed, it could be argued that the notion of a pervasive literary dialogics first became relevant at precisely the historical moment when technology — in this case, print technology — acted to multiply and explode the social relations of expression and representation. It is this technologically induced explosion, driving vernacular circulation, that energized in Venice the sort of cultural heteroglossia — that undergrowth of tangled meanings — that Bakhtin described. In early modern Venice, as in the novels Bakhtin discusses, there was a correlated factor at work too: namely, a socially embedded process of imitation that cannot be conceived apart from the multivocal character of Venetian literary production. Imitation functioned as a primary mechanism of vernacular circulation. Through the processes of imitation, tropes and gestures were appropriated and revised, reproduced and perpetuated.[2]

Many of the materials that proliferated through imitation were drawn from Petrarch's rime, which came to be treated as a form of fetishized booty.[3] In Chapter 5 I show how Venetian spokesmen for language canonized Petrarch's lyrics as the proposed basis of an official "monological" rhetoric. Yet the city simultaneously remade these lyrics into what W. Theodor Elwert dubbed some time ago a "Petrarchismo vissuto,"[4] a lived Petrarchism that propelled Petrarch's tropes through various cultural reproductions as a virtual form of mimetic capital. Thus at the same time as Petrarch's language affirmed images of Venetian civic identity through its august façade of subjective restraint, his lyrics furnished a cruder source of cultural capital for the city's appropriative strategies of imitation. In these

[2] This accords with the "expansive and associative" tendencies of the mid-sixteenth-century lyric described by Carlo Dionisotti, as discussed by Roberto Fedi, La memoria della poesia: canzonieri, lirici, e libri d'amore nel rinascimento (Rome, 1990), p. 46. Fedi's thesis regarding the linguistic and generic diffusion caused by the form of the raccolta, the lyric anthology, is also relevant (see esp. pp. 43-45).

[3] For a stimulating consideration of how print technology bears on the production of Petrarchan commentaries see William J. Kennedy, "Petrarchan Audiences and Print Technology," Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies 14 (1984): 1-20. Related issues are taken up in Fedi, La memoria della poesia, and Roland Greene, Post-Petrarchism: Origins and Innovations of the Western Lyric Sequence (Princeton, 1991), Introduction.

[4] See Elwert's "Pietro Bembo e la vita letteraria del suo tempo," in La civiltà veneziana del rinascimento, Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Centro di Cultura e Civiltà (Florence, 1958), pp. 125-76.

imitative processes dialogic modes figured strongly, even in lyrics: by turning Petrarch's internal, self-reflexive poetics inside out, replacing the absorbed introspection of an inward gaze with the reciprocal modes of observation, address, and realistic description, sixteenth-century lyrics often externalized Petrarch's poetics in interactive plays on real-life personalities.

This three-pronged phenomenon — mechanical reproduction, imitation, circulation — is distilled in Stephen Greenblatt's expression "mimetic machinery," as recently employed in Marvelous Possessions to situate exploration narratives within "social relations of production."[5] Like the voyagers and readers he depicts there, my patrons and composers interacted dialectically in "accumulating and banking" figures and images to "stockpile" them in "cultural storehouses." Musical figures meticulously collected and ordered their tropes in books, archives, galleries, and libraries, whose form and content hold the clues to the mimetic practices they employed. For this reason my immediate concerns with both Petrarchizing and printing do not turn in this chapter on the ideas and tropes Petrarchized per se. Rather, like Natalie Zemon Davis (to whom Greenblatt codedicates his book) and like numerous others following her lead, I look at how such storehouses served, in Davis's phrase, as "carriers of relationships."[6]

It may seem curious to probe these relationships through an ostensibly literary phenomenon, when music is at issue. Yet two cases that I will juxtapose below show how composers as well as their patrons exploited "dialogic" writing (broadly conceived) in mutually advantageous ways, profiting if passively at times from verbal interactions that were the typical province of men and women of letters. Not only

[5] See Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World (Chicago, 1991), pp. 6 and passim. The notion of circulation builds on Greenblatt's earlier Shakespearean Negotiations: The Circulation of Social Energy in Renaissance England (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1988).

[6] See "Printing and the People," in Society and Culture in Early Modern France (Stanford, 1975), p. 192. The groundwork for an understanding of printing as a facet of social geography in the early modern period was laid in large part by Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin in 1958 with L'apparition du livre; in English The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450-1800, trans. David Gerard, ed. Geoffrey Nowell-Smith and David Wootton (London, 1976), esp. Chap. 8, "The Book as a Force for Change." Thereafter came Marshall MacLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (Toronto, 1962), and the monumental study of Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early Modern Europe, 2 vols. (Cambridge, 1979), abridged as idem, The Printing Revolution in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, 1983). MacLuhan's and Eisenstein's studies have been charged with overemphasizing print's break with past oral and manuscript cultures, in part because of their concentration on intellectual developments in elite, nonephemeral, and relatively mainstream forms of print, by contrast with Febvre and Martin's more sociological approach. Davis's essay represents an early attempt to assess early modern printing in its social relation to nonelite cultures. Her microhistorical approach has been widely favored in recent works dealing with a great variety of printed objects, readers, and modes of circulation. The most vigorous voice in current discussions of print culture in the early modern period is Roger Chartier's; see esp. his explanations of the concept of "print culture" in the introduction to The Culture of Print: Power and Uses of Print in Early Modern Europe, trans. Lydia G. Cochrane, ed. Roger Chartier (Princeton, 1989), pp. 1-10; and Roger Chartier, The Cultural Uses of Print in Early Modern France, trans. Lydia G. Cochrane (Princeton, 1987). Others have followed Chartier's lead in stressing the anxieties generated by print possibilities and the awkward coexistence of print culture with manuscript culture (a theme I take up briefly in Chaps. 4 and 6); see the various essays in Print and Culture in the Renaissance: Essays on the Advent of Printing in Europe, ed. Gerald P. Tyson and Sylvia S. Wagonheim (Newark, Del., 1986); and Printing the Written Word: The Social History of Books, Circa 1450-1520, ed. Sandra L. Hindman (Ithaca, 1991).

were musicians and musical patrons often part of these dialogic encounters, but the circulation of dialogic varieties of imitation was frequently animated by the unorthodox forms in which they took shape.

In the pages that follow I construct a complementary pair of case studies around two patrons who were long-term residents in Venice. One involves the aspiring immigrant patron Gottardo Occagna. Between 1545 and 1561 Occagna was made dedicatee of at least three books of madrigals and recipient of various letters and literary dedications by Girolamo Parabosco. He died in Venice in 1567, but nothing is known of the last six years of his life. The other involves the Venetian nobleman Antonio Zantani, who died the same year. Zantani sponsored the main musical circle in mid-cinquecento Venice and amassed significant collections in various fields of graphic arts. He was also husband to a beauty exalted in the dialogic and musical literature of the time. By considering the complicities and agendas encoded in writings that accumulated around them, I will try to describe the sensibilities, ideological investments, and social connections with which their patronage of Venetian repertories was aligned.

Gottardo Occagna

Let me begin by sketching what I can of Occagna's biography, heretofore unknown. Occagna drew up a will in Venice on 19 February 1548 (see Appendix, A).[7] There he reveals, true to his name, that he is a Spaniard from the little town of Ocaña near Toledo, who has been living for an unspecified length of time in Venice. He calls himself "Gottardo di Ochagna at present resident here in the city of Venice." He names Alfonso de Benites as his father and Suor Maria di San Bernardo, "a nun in the monastery of Seville called Santa Maria di Gratia," to whom he leaves one hundred ducats, as his mother. His brother, to whom he leaves the same sum, he describes as a Dominican monk in the order of the "observanti." Others whom Occagna mentions were also apparently Spanish: an Alberto Restagno de la Niella; his wife, Paula; and a couple named Anzola and Hieronimo Barcharolla.

Occagna's will attests to a certain worldliness and wealth. He refers to the unnamed parts of his estate as being "both here in Venice and in Spain and in every other place." Outside his family his closest connections seem to have been Genoese: his "executor, commissary, and sole heir" Zuanagostino de Marini, in whose house he was staying in the parish of San Moisè; and a "Lorenzo Sansone genovese da Savona fiol de misier Raymondo mio carissimo." As a maritime, colonializing, and commercial city, Genoa

[7] Since Occagna's notary used the Venetian calendar, beginning on March 1, the date 19 February 1547 (as it is given) means 1548 in modern usage. So far as I can determine, this is the only document Francesco Bianco notarized for Occagna, nor have my searches of other notaries in the city thus far turned up other documents connected with him (despite the fact that Occagna "cancels and annuls all other testaments previously spoken, written, or ordered" by him).

I am extremely grateful to Giulio Ongaro for his expertise in helping me transcribe and interpret this and other archival documents discussed in Chap. 3. I also wish to thank Julius Kirshner and Ingrid Rowland, especially for help with some of the Latin.

in some ways resembled Venice. It excelled at navigation and cartography, shipbuilding and various industrial techniques, as well as banking. Once the Genoese shifted in 1528 from serving France to the imperial Charles V of Spain, they also began to manage huge sums and trading ventures for the Spanish crown. Occagna's dual Spanish and Genoese connections thus probably point to mercantile (or possibly diplomatic) activities along a Spanish-Genoese-Venetian axis.

Nothing tells us what the mix of commercial and cultural attractions was that kept Occagna in Venice. Yet it's clear that he integrated himself into aspects of Venetian cultural life in ways other foreign businessmen and diplomats might have envied. One of the recurring concerns of his will, for instance, were the various institutions of charity central to the consciousness of counter-reformational Venetians. Like so many of the city's residents, Occagna had joined a large lay confraternity, the Scuola di Santa Maria della Carità, to which he left twenty ducats so as to have the brothers accompany his body to its burial. He left ten ducats each to the hospitals of the Incurabili and Santissimi Giovanni e Paolo.

Beyond these standard gestures Occagna described himself as fiscal sponsor of a young girl ("putina") Valleria, to whom he had apparently been lending continuous financial assistance ("facto arlevare") for some time through her caretaker, Anzola Barcharolla.[8] For the girl's future marriage or (more likely, as he concedes) her entrance into a convent, he set aside twenty ducats. Such a practice is common enough in wills of the time,[9] but why Occagna should have provided for the child's long-term maintenance is a mystery that suggests a deeper connection — parenthood, either his own or that of a good friend or servant.

While Occagna's will reveals him as well assimilated into Venetian cultural institutions and practices — particularly those involving charity but surely also the larger panoply of rituals connected with church and scuola — nothing in it suggests how he was drawn so far into the world of music and letters. Yet we should bear in mind that charitable, religious, and mercantile activities gave ample opportunities for expanding cultural connections from a position outside the establishment — from a position, that is, outside the local patrician class.[10]

[8] Apparently the Barcarollas, who lived at San Barnaba, were servants to the French ambassador, though at what rank Occagna does not say.

[9] Among personalities discussed in the present study, we encounter it in the wills of Adrian Willaert (see Chap. I above, n. 15), Elena Barozza Zantani (as discussed in the present chapter), and Veronica Franco; for the last see Margaret F. Rosenthal, The Honest Courtesan: Veronica Franco, Citizen and Writer in Sixteenth-Century Venice (Chicago, 1992), Chap. 2, pp. 65-66, 74-84.

[10] Occagna's involvement in the scuole grandi, which hired top singer-composers to freelance on special occasions, represents one instance of his cultural networking. (On the hiring of singers at the scuole grandi see Jonathan Glixon, "A Musicians' Union in Sixteenth-Century Venice," JAMS 36 [1983]: 392-421.) For a fine exegesis of the role assumed in sixteenth-century Venice by local and foreign merchants, including the ways they moralized their positions through codes of honor and virtue and tried to improve their cultural status through the acquisition of musical skills and instruments, see Ugo Tucci, "The Psychology of the Venetian Merchant in the Sixteenth Century," in Renaissance Venice, ed. John R. Hale (London, 1973), pp. 346-78, esp. pp. 364-69; see also idem, "Il patrizio veneziano mercante e umanista," in Venezia centro di mediazione tra oriente e occidente (secoli XV-XVI): aspetti e problemi, 2 vols., ed. Hans-Georg Beck et al., Fondazione Giorgio Cini (Florence, 1977), 1:335-58.

9.

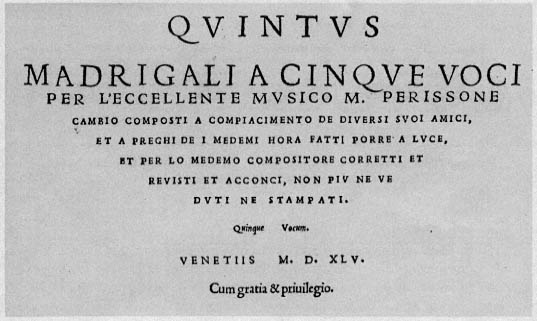

Perissone Cambio, Madrigali a cinque voci (Venice, 1545), title page, quintus part book.

Photo courtesy of the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, from 2.15.14-18 Musica (4).

Occagna's earliest public link to vernacular arts comes from a composer who is known to have freelanced at the Carità in later years, Perissone Cambio.[11] Perissone dedicated his first print, the Madrigali a cinque voci, to Occagna in 1545 (Plates 9 and 10). The print was mutually expedient in aiding the aspirations of both dedicator and dedicatee. In 1545 Perissone had only recently arrived in Venice and was still jobless.[12] Although he had managed to attract some attention as a first-rate singer and promising madrigalist (as attested by Doni's Dialogo della musica and other anthologies from 1544), no position within the San Marco establishment could be secured for him until 1548. In order to issue the Madrigali a cinque voci, he took his career into his own hands by submitting an application to the Senate for a printing privilege in his name (a practice that was usually carried out by printers). The privilege was granted not for any ordinary settings of madrigals or ballatas but for "madrigali sopra li soneti del Petrarcha."[13] Shortly thereafter the Madrigali were issued without a printer's mark as a sort of vanity print.[14]

[11] On Perissone's connection with the Carità from 1558, see Glixon, "A Musicians' Union," pp. 401 and 408.

[12] See further on Perissone's biography in Chap. 9 nn. 27-30, 38. The best source of biographical information on Perissone is Giulio Maria Ongaro, "The Chapel of St. Mark's at the Time of Adrian Willaert (1527-1562): A Documentary Study" (Ph.D. diss., University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 1986).

[13] See Chap. 9 n. 38.

[14] In the dedication Perissone says that he is having some of his madrigals for five voices printed ("facend'io stampare, alcuni miei Madrigali, à cinque voci").

10.

Perissone Cambio, Madrigali a cinque voci (Venice, 1545), dedication to Gottardo Occagna.

Photo courtesy of the Herzog August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel, from 2.15.14-18 Musica (4).

Perissone had clearly found a collaborator in the venture in Occagna. Both on the title page and in the dedication Perissone stressed the fact that encouragement from friends who wanted the music for their own use had been his incentive to print it. As his title page put it, these madrigals had not only been "composed for the pleasure of various friends of his" but were only being "brought to light at their request" (emphasis mine). The music Occagna and his friends presumably wanted (and may already have been singing) included the newest and trendiest sort — mostly Petrarch's sonnets set in a motetlike style, though leavened with a few lighter texts done in a more arioso Florentine manner. Only one collection of music had previously been printed in Venice that was at all comparable to this one, namely Rore's First Book from 1542. Perissone's was the first serious attempt to appropriate the style of Willaert and Rore, even quoting from Willaert's unpublished settings of Petrarch. Despite its unassuming origins, then, Perissone's book bore public witness to the new position Occagna had acquired via Petrarchan fashions among the city's cultural elite.

Only a larger dialogic context helps us read the alliances through which Occagna acquired this and other coveted accoutrements of patrimony and patriarchy, a context chiefly provided by various Petrarchizing addresses made to Occagna by Parabosco. Occagna surfaced as literary patron to Parabosco in the same year as Perissone printed his Petrarchan madrigals. Parabosco dedicated to him the first in his series of epistolary handbooks called Lettere amorose, zany anthologies of formulaic letters for different amorous situations. These letters extended the familiar letter genre, resurrected for the vernacular by Pietro Aretino only in 1537, into the domain of popular love theory that had been made so fashionable early in the century with Pietro Bembo's Gli asolani of 1505.[15] Accordingly, the Lettere amorose

[15] On Aretino's resuscitation of the familiar letter genre see Amedeo Quondam, Le "carte messaggiere": retorica e modelli di comunicazione epistolare, per un indice dei libri di lettere del cinquecento (Rome, 1981), and Anne Jacobson Schutte, "The Lettere Volgari and the Crisis of Evangelism in Italy," RQ 28 (1975): 639-88.

mixed in a smattering of letters, purportedly to various acquaintances, along with avowedly fictitious and generic ones.

Parabosco specially contrived a dedication that would enfold Occagna in the letters' intimate world. He declined to adopt the obsequious rhetoric conventional in high-styled dedications, advancing in its place the more impertinent tone of eclectic satirists whom Aretino epitomized. Parabosco names three reasons for making this gift: first, knowing Occagna's delight in reading "opere volgari" (he was an afficionado of vernacular letters); second, as a sign of love; and third, because Occagna, who once thought Parabosco an adventurer in love, now knows how far from the truth he had been, as proven by those letters written to assuage his grief. With no further hint, he adds, Occagna will know which were dictated by real passion and which composed fictitiously for the pleasure of friends.[16]

The familiarity Parabosco risked in the 1545 dedication was only a preamble to what was to come in the expanded second edition issued the following year. There he attached an Aggiunta in the form of three letters, one to Occagna and two addressed anonymously, plus an extra pseudoletter to Occagna that formed in reality a dedication to the Aggiunta.[17] (The typography of this last letter, as printed in the 1549 edition, helps make the letter's dedicatory function clear; see Plate II).

In the first of the letters Parabosco upped the ante of familiarity in a way that exposes Occagna's complicity in being honored by jocular informality rather than groveling decorum.[18] Parabosco begins by answering Occagna's purported request to explain the workings of the "three [types of] love" (the "tre amori"). In the slow unraveling of allusions that follows, the reader is positioned as privileged onlooker to a private male exchange. Within it, Parabosco tropes the basic Petrarchan tension of an eternally frustrated male infatuated with a chaste, unattainable woman. Yet he quickly and radically alters Petrarchan voice and address. One of the "tre amori" depicts love as a sportman's quest to attain the unattainable, while another celebrates the sweetness of requited love. Unlike Petrarch's poet, who always addresses (ultimately) himself, Parabosco's letters reverse this self-referential strategy to address another lovelorn male. Thus while Parabosco weaves his strands from the private conceits and postures of Petrarch's rime, he assumes an ironic — but typically

[16] Here is the bulk of the dedication to the Lettere amorose: "Al Nobile, et Generoso Sig. Gottardo Occagna. Tre sono le cagioni . . . che mi spingono à farvi dono di queste mie lettere amorose, l'una per conoscer io V.S. dilettarsi & haver sommo piacer di legger l'opere volgari; l'altra per dar segno a quella dell'amore, & della servitù, ch'io le porto, havendomi à ciò astretto le sue infinite virtù la terza perche conosciate homai, quanto sete lontano del vero, ogni volta che crediate, ch'io sia aventurato nell'amorose imprese, come dite, & di questo ve ne daranno non picciol segno quelle lettere lequali sono scritte, come vederete, piu tosto per disacerbere il dolore, che per speranza di muover pietà ne di altrui cuore. Quelle di tal soggetto la maggior parte della propria passione dettate sono, le altre poi à piacer di diversi miei amici composi. V.S. che è saggio, conoscerà molto bene dall'effetto quelle da queste, però io non le ne darò altro segno." Signed 12 June 1545.

[17] I am grateful to Kenneth A. Lohf of Columbia University's Rare Book and Manuscript Library for checking the edition of 1546 and to Jill Rosenshield of Special Collections at Memorial Library of the University of Wisconsin for checking editions printed in 1549 and 1561.

[18] For a full transcription of the letter see Appendix, B, Paraboso, I quattro libri.

11.

Girolamo Parabosco, Lettere amorose (Venice, 1546), "Aggiunta al

valoroso Signor Gottardo Occagna," fol. 79'.

Photo courtesy of Van Pelt Library, Special Collections, the

University of Pennsylvania.

Venetian — position of doubleness, a doubleness in which the subjects' public words annul the implication of intimacy even as they allege it.

Parabosco's letter also inverts parodistically the male-female relation of Petrarch's poetry, as made clear in the second type of love, consisting of a male tactic designed to conquer a particular sort of woman who is won over by the spectacle of a man wallowing in his amorous obsession for her. From their male perspective this is a "sweet love, since loving one of this sort, one . . . doesn't have to suffer through [all] the usual effort." The end is not only attained, but the route to it is eased and quickened. Parabosco claims a man may reach his desired goal by the very act of obsessing over it (or, as he says, through the act of "ruminating"), since his coy behavior softens the sympathetic woman. ("How many have there been," he asks, "who have found remedies in cases like this at a point when the wittiest men in the world would not have imagined one in a thousand years?") The amorous huntsman can therefore chalk his catch up to the wits of his own female quarry, who actually exploits his exaggerated grief to justify her tacit but eager complicity in the lovers' game.[19] Parabosco claims to rejoice when friends pull off stunts like these. "[M]y Lord, it doesn't displease me but makes me happy whenever I see a friend of mine giving himself as prey for the loving of such a subject — of which I will say nothing else because I know that you know much better than I the sweetness that one draws from that" (emphasis mine).[20] The master at this wily love game, Parabosco would then claim, is Occagna himself, the one who arguably backed both print and reprint.[21] This implies a collusion between them not in matters of love but rather in elaborating iconoclastically Petrarch's outer theme of innamoramento, of falling in love, to mutually accommodating ends: the double position Parabosco seems to assume in doing so — standing at once between private and public, between inward and outward, and between sober and comic — must be understood as equally Occagna's.

Such subversive inversion is, of course, defined and bound by the thing it subverts, Parabosco's anti-Petrarchism by definition Petrarchan. Several passages from the Aggiunta affirm this duality: one of them glosses side by side two of Petrarch's

[19] A passage taken from fols. 104-104' translates: "Oh the great happiness of a lover who is able to see his ultimate goal being fastened, almost in spite of fortune, on his desire through the sublime intellect of his lady. Who could imagine the sweetness that that fortunate man then feels who is at once assured of the love of his beloved and of loving a thing of tremendous value, since the intelligence of the one he loves is no less proven to him than her affection. Beyond that, the man of this second ardor, being of a warm character, can always have more hope of attaining his intended goal than can any other [sort of man]; and no less because of the excuses that such ladies make for his pity than because of their sympathy, each of which they use in similar ways. Those ladies don't have any need to show all that harshness that they are accustomed to enjoy in loving well, because they are so eminent in it or at least much pledged to it. For which reason they are almost always disposed to receive a loving fire."

[20] Fol. 104'.

[21] Note that the final dedicatory letter to Occagna, included in the Aggiunte in the editions of 1546, 1549, and 1558, strongly suggests that Occagna was an actual financial backer (see Plate 10). Although the letter was deleted from Gabriel Giolito's edition of 1561, along with the dedications to Occagna of Books 1 and 3, that of Domenico Farri (another Venetian publisher) dedicated each of its four separately printed books to Occagna in the same year, according to Giuseppe Bianchini, Girolamo Parabosco: scrittore e organista del secolo XVI, Miscellanea di Storia Veneta, ser. 2, vol. 6 (Venice, 1899), p. 482.

sonnets — indeed two out of the sixty or so sonnets that were set by Parabosco's teachers and colleagues;[22] while two other passages avow in the most ubiquitous of Petrarch's oxymorons, that of the icy fire, an ardor that destroys and melts the coldest ice.[23]

Parabosco's letters thus suggest several things about the position an upwardly mobile patron like Occagna might assume toward those he patronized: first, that as dedicatee, he was a willing interlocutor in an exchange that made the private public — or pretended to; second, that his tacit participation in literary exchanges formed part of a larger world of vernacular discourse, which embraced music along with various sorts of letters; and third, that a primary discursive mode for all these — and a yardstick from our vantage point — was the collection of tropes provided by Petrarch's lyric sequence. Parabosco (to trope myself) inverts Petrarch's lyric stance in order to stand in it: the unattainable woman becomes attainable, chaste womanhood becomes unchaste, the silent woman (by implication) becomes vocal, and the writer who speaks to himself now speaks out to others. As the internal spiritual struggle of Petrarch's lyrics is externalized in the implicit dialogue of the familiar letter, the most defining aspect of Petrarch's stance is turned inside out. Literary voice and content thus collaborate to lower Petrarch's canonized style to the level of a vulgar popularization.

The very different transformations of Petrarchism that I have noted in Perissone and Parabosco — Perissone's sacred-style Petrarch settings and Parabosco's irreverent verbal plays on Petrarchan poetics — play (broadly speaking) with Venice's tendency at this time to separate styles into high and low. Through its dialogic modes, authors could often slip freely between styles that were otherwise strictly separated. Occagna received two further dedications in the 1540s that exemplify more straight-forwardly Venice's tendency at midcentury to stratify styles along such Ciceronian lines. Both match verbal subjects, already matched to linguistic registers, to particular musical idioms.

The first of these came again from Parabosco, but the music was not his. Instead Parabosco dedicated to Occagna a book of mascherate by an apparently obscure composer named Lodovico Novello.[24] According to the dedication, Occagna

[22] See his discussion of the third type of love in the letter given in Appendix, B, I quattro libri, which conflates Petrarch's sonnet no. 253, v. 1, with sonnet no. 159, v. 14: "O dolci sguardi, o dolci risi, o dolci parole, che dolci sono ben veramente più che l'ambrosia delli Dei" (fols. 104'-5).

[23] These occur at the end of the first letter: "laqual cosa è troppo a far felice un'huomo, ilquale sarebbe degno d'infinita pena, se havendo cotal commodità non rompesse un diamante, o non infiammasse un ghiaccio" (fol. 105); and in this passage from the third: "rompa homai la mia fedeltà la vostra durezza; il mio ardor distrugga, & consumi il freddissimo ghiaccio, & la crudeltà, di che havete cosi cinto il core: accio ch'io canti ad un tempo & la bellezza, & la cortesia di chi a suo piacer mi puo donar morte, & vita" (fol.108').

[24] Title: Mascherate di Lodovico Novello di piu sorte et varii soggetti appropriati al carnevale novamente da lui composte et con diligentia stampate et corrette libro primo a quatro voci. The dedication reads: "Al Nobile et gentil Signor Gottardo Occagna/Girolamo Parabosco. Carissimo signor mio, quando io mi ritrovassi privo di quello che da v.s. mi fosse richiesto io me ingegnaria di farmi ladro per contentarvi ne fatica ne timore alcuno o di vergogna o di danno che avenir me ne potesse mi farebbe rimener giamai di cercare ogni via per che fosse adempiuto il desiderio vostro & mio. Essend'io adunque a questi giorni stato richiesto da V.S., di alcune imascherate, & havendo per mille negotii importantissimi come tosto vi sara manifesto l'animo in piu di mille parti diviso io non poteva veramente in modo alcuno servire la S.V. del mio, & mentre mi pensavo ond'io potessi o rubarle o d'haverle in duono fuor d'ogni mio pensiero & senza alcuna mia diligenza quasi per miracolo mi sono venute alle mani queste composte per lo eccelente M. Lodovico Novello per lequali V.S. potra essere apieno sodisfatta d'ogni suo desiderio per che ce ne sono in ogni soggetto ma tutte ugualmente dette con bella & acuta maniera & facile senza molta gravita come si conviene, & cosi il canto come le parole accio che da tutti siano intese & gustate. lo le dedito a V.S. con licenza di chi ha carico de farle stampare. Di queste come V.S. potra vedere tutte le stanze che seguiranno la prima si cantano sopra le noti di essa prima ne qui alcuno potra pigliare errore per che altro canto non ci e che de una sola stanza per ciaschaduna imascherata salvo che di tre, quali sono questi: i gioiellieri, gli fabri, & i Ballarini. di queste tre l'ultima stanza di ogniuna ha un Canto per se & tutte le altre si cantano come la prima, come si comprendera chiarissimamente V.S. le accetta con lieto animo & mi comandi." I add punctuation to a transcription taken from Mary S. Lewis, Antonio Gardane, Venetian Music Printer, 1538-1569: A Descriptive Bibliography and Historical Study, vol. I, 1538-49 (New York, 1988), pp. 527-28, which also includes a list of the print's contents.

It does not seem implausible that "Lodovico Novello" was a pseudonym for Parabosco.

wanted newly fashioned songs as entertainment for the carnival season and hoped Parabosco could author them. The composer pleaded himself overcommitted, which can hardly have been far from the truth, insisting that he would have stolen them and suffered any shame, damnation, or exertion to procure them had he not chanced miraculously on the four-voice mascherate by Novello. Somehow Parabosco was acting as intermediary between Novello and the printer Antonio Gardane, with whom he must have had a working alliance, for he claimed to make the dedication with the "license of one who has the task of having them printed" (emphasis mine). These mascherate cover "every topic, but all with equal beauty, wit, and ease, and without much gravity, as is fitting," so that "both the melody and words can be understood and enjoyed by everybody." By "every topic" Parabosco means every mask, every get-up — of which there are a great variety: mascherate "Da hebree," "Da mori," "Da nimphe," "Da rufiane," "Da scultori," "Da calzolari," "Da vendi saorine," "Da orefici," "Da maestri di ballar," "Da porta littere," "Da fabri," and so on (masks of Jewesses, Moors, nymphs, procuresses, sculptors, shoemakers, mustered vendors, goldsmiths, dance masters, postmen, locksmiths). Occagna's circle must have planned to sing them themselves (just as they sang Perissone's madrigals), for Parabosco closes with advice on how they should go about matching the stanzas to the melodies.

The texts allowed plenty of ribald humor and artisanal double entendre: doctors who nimbly probe the love sores of willing patients; locksmiths who "screw in keys" free of charge.[25] Woven between their lines is a sophisticated tapestry of intertextual references to other lyrics, frottole, dance songs, napolitane, epic verse, comedies, and madrigals. Thus the songs could amuse the cognoscenti and invert the official rhetoric they knew all too well, without perplexing the uninitiated.[26]

[25] The unpublished transcriptions of texts and scores on which I base my discussion of Novello's print are those of Donna Cardamone Jackson. I am very grateful to her for loaning them to me.

[26] On the question of how carnival rites served as a "foil" to official rhetoric see Linda L. Carroll, "Carnival Rites as Vehicles of Protest in Renaissance Venice," The Sixteenth Century Journal 16 (1985): 487-502. Relevant too is the now widely read study by Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, trans. Hélène Iswolsky (Bloomington, 1984).

Many of the masks work Petrarchan figures into their repertory of inside jokes. The mask of the mailmen, for instance, beseeches the "lovely ladies" it addresses to post their love letters with them. But if a killing love death should demand discretion, it offers to send their messages by word of mouth ("a bocca dire") — carnal messages that tell, for instance, "How love makes you die and the spirit and food of a hot impetuous passion, which consumes your afflicated heart, join flesh to flesh and skin to skin."[27] Figures like the "cor afflitto che abbruccia" (afflicted heart that burns) and "amor che fa morire" (love that makes you die) circulated rampantly as common versions of Petrarchan tropes. Thus whoever wrote the texts had no lack of models close at hand. The precise phrase "Amor mi fa morire" was, in fact, well known to Venetian afficionados of vernacular music like Occagna and company, for it troped the incipit of a well-known ballata-madrigal set by Willaert and widely circulated in the 1530s.[28] All the funnier therefore that it should appear here in a raucous, strophic part song. The modest bits of contrapuntal imitation that Novello incorporated into his mascherata did nothing to elevate the songs' generally low idiom, their gawky tunes, and sudden metric shifts. On the whole the masks were better suited to outdoor revelries than to genteel drawing rooms, where quiet, ceaseless polyphony was the norm.

This, then, is low style pure and simple, and its proper place is carnival: in short, low style for carnivalesque subjects. At this lower rung of mascherate also sat spoken comedy. In 1547, for the third year in a row, Parabosco dedicated a vernacular work to Occagna, this time his comedy Il viluppo, citing Occagna's pleasure in reading "simil Poemi."[29] Reading the play aloud — reciting it in a group, that is — may be what Parabosco had in mind, a practice that was widespread among the literate.[30] Here again we find Occagna in the thick of the newly ascendant vernacular arts, engaging in the play of Petrarchism made part of daily life and relishing the diverse styles and levels that the new Ciceronian conceptions of words prescribed.

The high-styled antithesis to masks and comedies came with a work dedicated to Occagna in 1548, attached to an early edition of Rore's Third Book of madrigals printed by Girolamo Scotto (RISM 15489 ).[31] This dedication assigned Occagna the

[27] The passage comes from stanza 3 of the mascharata "Da porta lettere": "Se voleti a bocca dire/Qualche cosa et non inscrito/Come amor vi fa morire/Et ch'il spirto vostro e vitto/D'un focoso e gran desire/Che v'abbruggia il cor afflitto/Di congionger dritto adritto/Carne a carne e pelle a pelle."

[28] See Chap. 7 above, nn. 18-19.

[29] "[E]ssendomi venuto in proposto di stampare questa mia nova Comedia, quale ella si sia, a Vostra Signoria la dono: & perche io so il piacere ch'ella ha di legger simil Poemi." Parabosco used the same address, "Al nobile, & generoso signore Gottardo Occagna."

[30] Cf. Donato Giannotti's letter to Lorenzo Ridolfi discussed in Chap. 2 nn. 63-64.

[31] The book was printed about the same time as or slightly earlier than an equivalent one by Gardane (RISM 154910). The account books of the Accademia Filarmonica of Verona show that it purchased one of the 1548 eds. (presumably Gardane's) on 19 April 1548; see Giuseppe Turrini, L'Accademia Filarmonica di Verona dalla fondazione (maggio 1543) al 1600 e il suo patrimonio musicale antico, Atti e memorie della Accademia di Agricoltura, Scienze e Lettere di Verona, no. 18 (Verona, 1941), p. 37. For bibliographical issues surrounding the print see Alvin H. Johnson, "The 1548 Editions of Cipriano de Rore's Third Book of Madrigals," in Studies in Musicology in Honor of Otto E. Albrecht, ed. John Walter Hill (Kassel, 1980), pp. 110-24, and Mary S. Lewis, "Rore's Setting of Petrarch's Vergine bella: A History of Its Composition and Early Transmission," Journal of Musicology 4 (1985-86): 365-409. Johnson argues that differences in the title pages of the two editions (there are actually two distinct ones in different part books for Gardane's) leave no doubt that Scotto's was published first; the title pages and dedications are reproduced in Johnson, pp. 111, 114-15, and 121. For the argument that both editions were published by April 1548 see Lewis, p. 381. Gardane's edition bore no dedication until the supplement was issued the following year (see below) and appended to the altus part book, which was dedicated by Perissone Cambio to the poet-cleric Giovanni della Casa.

slight place he has previously held in historical memory, for the print included Rore's setting of the first six stanzas of Petrarch's final canzone, Vergine bella. The brief dedication was signed not by the composer, however, but by the Paduan flutist Paolo Vergelli:

To the noble and valorous Signor Gottardo Occagna, my most eminent friend and Lord.

My most honored Lord and friend, I know the diligence and effort that you have used recently in order to have those Vergine, already composed many months ago by the most excellent musician Mr. Cipriano Rore, your and our most dear friend. Those works having come into my hands, it seemed to me [fitting], both because of the love I bear to you and to satisfy your desire, to have them printed with some other lovely madrigals by the same composer, and some by the divine Adrian Willaert and other disciples of his, so that you might not only be satisfied in your wish, but with it might even bring some praise and merit to the world, which thanks to you will be made rich by this present, truly worthy of being seen and enjoyed by everyone. I kiss your hands. Paolo Vergelli, Paduan musician.[32]

Contrary to Vergelli's claims, Scotto's edition of the Vergine cycle suggests that there was no such mutually beneficial collaboration between Occagna and Rore of the kind Occagna had had with Perissone (or Willaert and Rore with the Florentines). If anything, it hints that Occagna's aspirations broke down at such formidable levels. In fact, both bibliographical and musical evidence surrounding the edition make me think the enterprise was surreptitious.[33] First of all, the dedication was not authored by Rore — by then in Ferrara — but by Vergelli, probably as one of Scotto's freelancers. Vergelli noted that Occagna had been trying hard to get hold of the Vergine stanzas for some months. He also claimed that both he and Occagna were good friends of Rore's (whom he called "vostro e nostro carissimo amico"). Why then did they let the cycle

[32] "Al nobile & valoroso Signor Gottardo Occagna compadre & Signor mio osservandissimo. Signor compare honorandissimo. Sapendo io la diligenza, & la fatica che havete usata questi giorni passati per haver quelle vergine, gia molti mesi sono, composte da lo eccellentissimo musico messer Cipriano Rore, vostro et nostro carissimo amico, mi e parso, essendomi le predette compositioni venute alle mani, per lo amor che vi porto, & per satisfare al desiderio vostro, farle stampare con alcuni altri bellissimi madrigali del medemo compositore, & con alcuni del Divinissimo Adriano Villaerth, e de altri suoi discepoli, accio che vostra signoria non solamente sia satisfatta del desiderio suo, ma ne consegua ancora qualche laude & merito appresso il mondo, il quale merce di vostra signoria sara fatto riccho di questo presente, veramente degno di esser veduto, & goduto da ognuno. Et a V.S. baccio le mani. Paolo Vergelli musico padovano." The title page reads: Di Cipriano Rore et di altri eccellentissimi musici il terzo libro di madrigali a cinque voci novamente da lui composti et non piu messi in luce. Con diligentia stampati. Musica nova & rara come a quelli che la canteranno & udiranno sara palese. Venetiis. Appresso Hieronimo Scotto. MDXLVIII.

[33] Lewis reaches a similar conclusion in "Rore's Setting of Petrarch's Vergine bella," pp. 394-405.

be printed in a form so glaringly incomplete as both poetic and musical structure — especially given that Rore had been instrumental in introducing literary standards to Italian part music that aimed to set poems intact?[34] The six stanzas fell five short of the total eleven, leaving the canzone hanging in midair. Further, in such fragmentary form the music lacked the tonal unity supplied by the last five stanzas once Rore's settings of them were issued in a supplement the following year.[35] Even the supplement was probably only Rore's way of making the best of a bad situation: three years later, a new edition by Gardane included substantial revisions that Rore had made to the whole cycle. If Occagna hoped his identification with the Vergine settings would give him the kind of cachet that exiled Florentines got from Willaert's settings, he can only have half succeeded. The upwardly mobile might have envied him, while the real cognoscenti must have sneered at the clumsiness of the effort. Perhaps no one in 1548 could have reaped the benefits of a linkage to Rore's Vergine in a legitimate, public arena, but surely not Occagna.

With this evidence in hand we can begin to situate Occagna's position within the kind of ethnography of books I hinted at earlier, one that moves between bibliographical evidence and larger dialogic contexts. It is this hermeneutic move that allows us to consider the extent to which Occagna's link with the Vergine cycle put him in cultural company with the city's most select patrons.

What in fact could have been the mechanism that brought about this link, if in fact Occagna had no responsibility for the genesis of the music? Quite simply, he must have offered a subvention to Scotto's printing house. Vergelli probably procured the subvention as part of his moonlighting for Scotto, after having gotten hold of the unfinished music. Occagna for his part cannot have attended much to the niceties of its public debut when presumably he helped finance it. His connection with Rore's Vergine thus jibes with ones he made earlier with Parabosco and Perissone. Rather than maintaining his position privately, as nobles tended to do, these addresses and exchanges all helped advance publicly his fledgling reputation in Venetian society.

Occagna's involvements would have been intolerably reckless for the likes of most Venetian aristocrats. In addressing nobles, middle-class authors like Parabosco almost never employed the familiar versions of Petrarchan tropes that Occagna condoned. Even the more dignified tropes of praise that helped define noblemen's patriarchy — and that their patriarchy perpetuated — usually reached them only indirectly. I turn now to Antonio Zantani.[36]

[34] Although the trend for complete settings had previously been mainly toward sonnets, it was extended as early as 1544 to longer multistanza poems with cyclic settings of Petrarch's sestine Alla dolce ombra (no. 142) by Jachet Berchem, published in Doni's Dialogo della musica in 1544, and later to Giovene donna (no. 30) by Giovanni Nasco, issued in his Primo libro a 5 in 1548, the same year that Rore's Vergine appeared.

[35] The remaining five stanzas can be found as additions to a number of extant copies of the Terzo libro, as discussed by Lewis, "Rore's Setting of Petrarch's Vergine bella." For further discussion of the music, including the question of tonal unity, see Chap. 10, esp. n. 5.

[36] Primary sources give several variant versions of the name, including Zantani, Centani, Centana, and Zentani.

Antonio Zantani

Zantani gained notoriety in Venetian music history by attempting to print four madrigals from the Musica nova in the late 1550s. But his links to Venetian music date from at least 1548 and involve the same Scotto edition in which Rore's Vergine cycle was printed. Besides the settings by Rore, this edition included works by Willaert, Perissone, Donato, and others that enhanced its Venetian character.[37] Most of Willaert's contributions were occasional, forming part of the dialogic networks I have attempted to describe here. Among them was a dedicatory setting of Lelio Capilupi's ballata Ne l'amar e fredd'onde si bagna[38] a tribute to a renowned Venetian noblewoman whom Capilupi named with the epithet "la bella Barozza" — Antonio's wife.[39] Its praise of her sets the Petrarchan paradox of the icy fire in a verbal landscape shaped by Venetian geography: her flame, born in the cold Venetian seas, burns so sweetly that the fire from which the poet melts seems frigid beside it.

Ne l'amar e fredd'onde si bagna In the bitterness and cold in which

L'alta Vinegia, nacque il dolce foco The great Venice bathes itself was born the sweet fire

Ch'Italia alluma et arde a poco a poco. That inflames and illumines Italy bit by bit.

Ceda nata nel mar Venere, e Amore Venus, born of the sea, may yield, and Cupid

Spegna le faci homai, spezzi li strali May put out the torches and break his arrows;

Chè la bella Barozz'a li mortali For the lovely Barozza stabs the mortals

Trafigge et arde coi begl'occhi 'l core. And consumes their hearts with her beautiful eyes.

E di sua fiamma è sì dolce l'ardore, And there is such a sweet ardor from her flame

Che quell'ond'io per lei mi struggo e coco That that which makes me melt and burn for her

Parmi ch'al gran desir sia freddo e poco. Seems frigid and small beside the great desire.

Barozza's full name was Helena Barozza Zantani. In 1548 she already had a reputation as one of Venice's great beauties. She had been painted by Titian and Vasari, venerated by Lorenzino de' Medici, and widely celebrated in verse.[40] These tributes

[37] A number of these pieces reappear in the manuscript of the Herzog August Bibliothek in Wolfenbüttel, Guelf 293. See Lewis, "Rore's Setting of Petrarch's Vergine bella," pp. 407-8, for a list of its contents and concordances.

[38] The setting is among those in Wolfenbüttel 293. The poem appears in Rime del S. Lelio, e fratelli de Capilupi (Mantua, 1585), p. 31. For my identification of the poet I am indebted to Lorenzo Bianconi and Antonio Vassalli's handwritten catalogue of poetic incipits, which gave me the initial lead on this and a number of other poems.

[39] Many sources confirm that Helena was Antonio's wife, including Dragoncino's designation of his stanza "Consorte di M. Antonio" (see n. 42 below); Aretino's paired letters to "Antonio Zentani" and "Elena Barozza" from April and May 1548, respectively (Lettere di M. Pietro Aretino, 6 vols. [Paris, 1609], 4:207' and 208'; Lettere sull'arte di Pietro Aretino, commentary by Fidenzio Pertile, ed. Ettore Camesasca, 3 vols. in 4 [Milan, 1957-60] 2:215-17); and the wills of Antonio and Helena, as given in Appendix, C and D.

[40] Both portraits are described by Pietro Aretino and both are now apparently lost. Vasari's was painted before he left Venice in 1542 (cf. n. 86 below); see Aretino, Lettere, 2:304' (no. 420, to Vasari, 29 July 1542, with a sonnet in praise of Barozza) and 4:208' (no. 478, to Helena, May 1548, with reference to both portraits), and Lettere sull'arte 1:224 and 2:216-17.

On Lorenzino's unrequited feelings for Helena Barozza, and for the most thorough gathering of information on her, see L[uigi] A[lberto] Ferrai, Lorenzino de' Medici e la società cortigiana del cinquecento (Milan, 1891), pp. 343-52, esp. p. 347 n. 2.

placed Helena in the cult of beautiful gentildonne, which assigned Petrarch's metaphorical praises to living ladies and generated yet more goods for Venetian printers.[41] Of all these praises, those in lyric forms were most apt to adopt something close to the lightly erotic tone of Capilupi: Giovambattista Dragoncino da Fano's Lode delle nobildonne vinitiane del secolo moderno of 1547, for instance, devoted one of its stanzas to the "sweet war" Helena launched in lovers' hearts, ending in praise of her "blonde tresses."[42]

Other encomia conflated her beauty with her moral worth. Confirming the occult resemblance thought to exist between physical and spiritual virtue, they deflected the transgressive possibilities to allure and mislead the unsuspecting to which beauty was also commonly linked. A letter of Aretino's to Giorgio Vasari of 1542 honored Vasari's portrait of Helena for the "grace of the eyes, majesty of the countenance, and highness of the brow," which made its subject seem "more celestial than worldly," such that "no one could gaze at such an image with a lascivious desire."[43] Aretino troped his own letter in an accompanying sonnet, declaring her loveliness of such an honesty and purity as to turn chaste the most desirous thoughts (see n. 43 below). Lodovico Domenichi's La nobiltà delle donne similarly joined beauty with virtue by comparing Helena's looks with the Greek Helen of Troy and her honesty with the Roman Lucrezia ("Mad. Helena Barozzi Zantani, laquale in bellezza pareggia la Greca, & nell'honestà la Romana Lucretia . . .").[44] Even the female poet-singer Gaspara Stampa added to her Rime varie a sonnet for Barozza, that "woman lovely, honest, and wise" (donna bella, onesta, e saggia).[45]

Like most of the women exalted by this cult, the virtuous Helena was safely sheltered by marriage. This ideally suited her to the Petrarchan role of the remote and unattainable lady, as it was now employed for numerous idolatries of living women.

[41] For documentation of the literary activity generated by these cults see Bianchini, Girolamo Parabosco, pp. 278-98, and on Helena, pp. 294-96.

[42] Fol. [4].

[43] Verses 9-11: "Intanto il guardo suo santo e beato/ In noi, che umilemente il contempliamo,/Casto rende il pensiero innamorato (Lettere 2:304' and Lettere sull'arte 1:224).

[44] Fol. 261 in the revised version printed by Giolito in 1551. Domenichi was an interlocutor in Doni's Dialogo della musica and a Piacentine comrade of Parabosco's. The theme of Troy echoed again at the end of Parabosco's I diporti, as a group of Venice's most prominent literati enthuse over various Venetian women in the popular mode of galant facezie, in between recitations of novelle and madrigali. The Viterban poet Fortunio Spira exclaims, "Che dirò di te . . . madonna Elena Barozzi così bella, così gentile! oh! se al tempo della Grecia tu fossi stata in essere, in questa parte il troiano pastore senza dubbio sarebbe stato inviato dalla Dea Venere, come in luogo dove ella meglio gli havesse potuto la messa attenere!" See Giuseppe Gigli and Fausto Nicolini, eds., Novellieri minori del cinquecento: G. Parabosco — S. Erizzo (Bari, 1912), p. 192. (I diporti were first published in Venice ca. 1550; see Chap. 4 n. 30 below.) Also directed to Helena may be a letter and three sonnets in Parabosco's Primo libro delle lettere famigliari (Venice, 1551) addressed "Alla bellissima, et gentilissima Madonna Helena" and dated 30 April 1550 (fols. 49-50). Parabosco makes intriguing mention there of "il nostro M.A. ilquale compone libri delle bellezze, & delle gratie vostre: con certezza che gli possa mancar piu tosto tempo, che suggetto. io vi faccio riverenza per parte sua, & mia" (our Messer A., who composes books of your beauties and graces, with the certainty that he may be lacking time, rather than a subject. I revere you for his part and mine); fol. 49.

[45] Rime (Venice, 1554), no. 278; mod. ed. Maria Bellonci and Rodolfo Ceriello, 2d ed. (Milan, 1976), p. 264. On the tributes of Stampa and others to Helena Barozza see Abdelkader Salza, "Madonna Gasparina Stampa, secondo nuove indagini," Giornale storico della letteratura italiana 62 (1913): 31.

But it also suggests that the music, writings, and paintings in her honor participated in loose networks of reference and praise that helped situate familial identities within larger civic structures. Indeed, it raises the possibility that some were spousal commissions meant (like Willaert's madrigal) to embellish the domestic household and redound to the family name: Helena's husband, Antonio, could after all count himself among the most avid of aristocratic devotees to secular music at midcentury and a keen patron of the visual arts.

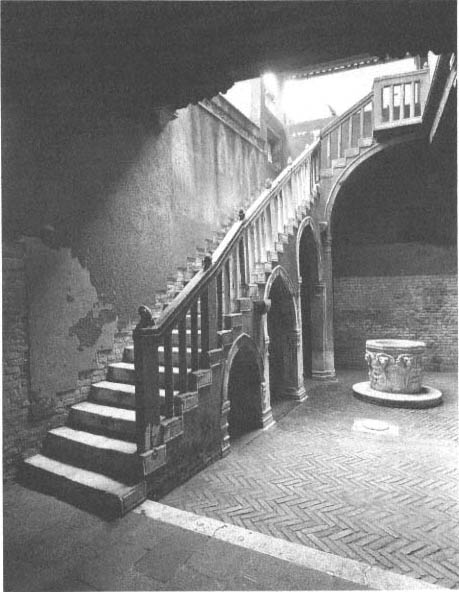

Zantani's vita will set the stage for reexamining relationships between civic identity and patronage at closer range.[46] Antonio was born on 18 September 1509 to Marco Zantani and Tommasina di Fabio Tommasini.[47] His father descended from a line of Venetian nobles, his mother from a family originally from Lucca and admitted to the official ranks of Venetian cittadini only in the fourteenth century.[48] In 1532 Antonio gained an early admission to the Great Council,[49] and on 16 April 1537 he and Helena were wed in the church of San Moisè.[50] Their respective wills of 1559 and 1580 identify their residence as being in the congenial neighborhood parish of Santa Margarita (see Appendix, C and D).[51] Inasmuch as Antonio's family clan was very small, they may also have lived at times, or at least gathered, at the beautiful Zantani palace nearby at San Tomà (Plate 12) — quarters that would have suited well the salon over which Zantani presided at midcentury.[52] Most famous of the earlier Zantani was Antonio's

[46] For a biography of Zantani see Emmanuele A. Cicogna, Delle inscrizioni veneziane, 6 vols. (Venice, 1827), 2:14-17. A briefer and more readily available biography, mainly derived from Cicogna, appears in Lettere sull'arte 3/2:528-30. Where not otherwise noted my biographical information comes from Cicogna.

The main contemporaneous biography is that given in the form of a dedication to Zantani by Orazio Toscanella in I nomi antichi e moderni delle provincie, regioni, città . . . (Venice, 1567), fols. [2] — [3']. It is reproduced in Appendix, E.

[47] I-Vas, Avogaria di Comun, Nascite, Libro d'oro, Nas. I.285. Marco and Tommasina were married in 1503 (I-Vas, Avogaria di Comun, Matrimoni con notizie dei figli).

[48] This information comes from Giuseppe Tassini's manuscript genealogy "Cittadini veneziani," I-Vmc, 33.D.76, 5:37-38, which, however, puts her marriage to Marco in 1505 (cf. n. 47 above). Tommasina drew up her will on 9 August 1566 (I-Vas, Archivio Notarile, Testamenti, notaio Marcantonio Cavanis, b. 196, no. 976), calling herself a resident of the parish of Santa Margherita.

[49] See Cicogna, Inscrizioni veneziane 2:14. (The date of 1552 given in Lettere sull'arte 3/2:528 is wrong.) On the practice of admitting young noblemen to the Great Council before their twenty-fifth birthdays see Stanley Chojnacki, "Kinship Ties and Young Patricians in Fifteenth-Century Venice," RQ 38 (1985): 240-70.

[50] I-Vas, Avogaria di Comun, Matrimoni con notizie dei figli. A marriage contract survives in the Avogaria di Comun, Matrimoni, Contratti L.4, fol. 381' (reg. 143/4), but is not currently accessible to the public.

[51] Helena's will was kindly shared with me by Rebecca E. Edwards. Cicogna refers to a will of 10 October 1567 that Zantani made just before his death, which is preserved in the Testamenti Gradenigo (Inscrizioni veneziane 2:16n.). Presumably it is included in the extensive Gradenigo family papers at I-Vas, which are as yet insufficiently indexed. (I am grateful to Anne MacNeil for inquiring about this.) Michelangelo Muraro cites an ostensible copy of the will at I-Vmc, MS P.D. 2192 V, int. 12, but the document in question is presently missing; Il "libro secondo" di Francesco e Jacopo dal Ponte (Bassano and Florence, 1992), p. 382. Cicogna quotes enough of this will, however, to show that Zantani took pains to have his name day celebrated every year thereafter: "Egli fu l'ultimo della casa patrizi Zantani, e col suo testamento ordinò che delle sue entrate fosser ogn'anno de' trentasei nobili dassero in elezione nel Maggior Consiglio."

[52] Zantani's clan died out with his death. Nonetheless, Pompeo Molmenti's statement that Antonio lived in the present Casa Goldoni is oversimple; see La storia di Venezia nella vita privata dalle origini alla caduta della repubblica, 7th ed., 3 vols. (Bergamo, 1928), 3:360-61. For the information, noted by Dennis Romano, that Venetian patrician families often had residences in several different parishes see Chap. 1 above, n. 1.

12.

Main staircase, Casa Goldoni, formerly Palazzo Centani (Zantani), parish of San Tomà.

Photo courtesy of Osvaldo Böhm.

grandfather of the same name, who had reputedly battled the Turks and been brutally killed and dismembered for public display while a governor in Modone.[53] According to one account, it was owing to "the glorious death of his grandfather" that Antonio gained his title of Conte e Cavaliere, bestowed with the accompaniment of an immense privilege by Pope Julius III, who occupied the papacy between 1550 and 1555.[54] Later in life Antonio served as governor of the Ospedale degli Incurabili. One of his memorable acts, as Deputy of Building, was to order in 1566 the erection of a new church modeled on designs of Sansovino.[55] He died before he could see it, in mid-October 1567, and was buried at the church of Corpus Domini.[56]

Music historians remember only two major aspects of Zantani's biography. The first is that he was foiled in trying to publish a collection of four-voice madrigals that included four Petrarch settings from the Musica nova, then owned exclusively by the prince of Ferrara. The second is that he patronized musical gatherings at his home — gatherings that involved Perissone, Parabosco, and others in Willaert's circle, as recounted in Orazio Toscanella's dedication to him of his little handbook on world geography, I nomi antichi, e moderni (given in full in Appendix, E).

It is well noted that you delight in music, since for so long you paid the company of the Fabretti and the company of the Fruttaruoli, most excellent singers and players, who made the most fine music in your house, and you kept in your pay likewise the incomparable lutenist Giulio dal Pistrino. In the same place convened Girolamo Parabosco, Annibale [Padovano], organist of San Marco, Claudio [Merulo] da Correggio, [also] organist of San Marco, Baldassare Donato, Perissone [Cambio], Francesco Londarit, called "the Greek," and other musicians of immortal fame. One knows very well that you had precious musical works composed and had madrigals printed entitled Corona di diversi.[57]

Among the recipients of Zantani's patronage, then, were guilds of instrumentalists and singers, solo lutenists, organists, chapel and chamber singers, and polyphonic composers (primarily of madrigals and canzoni villanesche ), several of them doubling in various of these roles. Both the Fabretti and the Fruttaruoli were long-established groups. The Fabretti were the official instrumentalists of the doge, performing for many of the outdoor civic festivals, and the Fruttaruoli a confraternity

[53] For modern biographies of Antonio's grandfather and father, see Cicogna, Inscrizioni veneziane 2:13-14.

[54] See Toscanella's dedication to Zantani, I nomi antichi, e moderni, fol. [3], with further on Zantani's family, heraldry, etc. The origins of Zantani's knighthood with Julius III would seem to be confirmed by a manuscript book on arms written by Zantani and titled "Antonio Zantani conte e cavaliere del papa Iulio Terzo da Monte," as reported by Cicogna, Inscrizioni veneziane 2:16. If Toscanella was right about the immense size of the privilege, this may account for Zantani's apparent increase in patronage in the early to mid-1550s.

[55] See Bernard Aikema and Dulcia Meijers, Nel regno dei poveri: arte e storia dei grandi ospedali veneziani in età moderna, 1474-1797 (Venice, 1989), p. 132, and Muraro, Il "libro secondo," p. 382.

[56] The church was secularized in 1810 and later destroyed; see Giuseppe Tassini, Curiosità veneziane, ovvero origini della denominazioni stradali di Venezia, 4th ed. (Venice, 1887), pp. 208-10. On Zantani's death date see Cicogna, Inscrizioni veneziane 2:16.

[57] See Appendix, E, fol. [2']. The passage was first quoted and trans. in Einstein, The Italian Madrigal 1:446-47.

that likewise performed outdoor processions.[58] Apparently Zantani paid members of both the Fabretti and Fruttaruoli over a considerable time and, as Toscanella's wording implies, also kept the lutenist dal Pistrino on regular wages, perhaps as part of his domestic staff. Toscanella did not mean to suggest that these musicians all convened ("concorrevano") at once, but he was calling up the idea of collective gatherings in the sense of private musical academies.[59]

Zantani's foiled efforts in music printing might be seen as part of a larger attempt to increase his familial patrimony. In approximately 1556-57 he assembled with the aid of another gentleman, Zuan Iacomo Zorzi, the musical anthology that eventually led to his confrontation with agents protecting the interests of the prince of Ferrara. The anthology was to be published with an ornate title page and with the title La eletta di tutta la musica intitolata corona di diversi novamente stampata: libro primo (Plate 13).[60] Zorzi contributed a dedication addressed to none other than Zantani himself (Plate 14) — this despite the fact that Zantani was not only the print's backer but in reality its chief owner and producer. Zorzi's dedication praised

[58] The latter were named for their renowned promenade on the so-called Feast of the Melons, which reenacted an occasion when they had been feted with melons by Doge Steno — an honor that they repeated ritually in every first year of a doge's reign by bearing melons in great flowered chests and small silver basins on a certain day in August and processing with trumpets, drums, and mace bearers from the campo of Santa Maria Formosa through the Merceria and piazza San Marco to the Ducal Palace. For further information see Giuseppe Tassini, Curiosità veneziane, ovvero origini delle denominazioni stradali di Venezia, rev. ed. Lino Moretti (Venice, 1988), pp. 266-67: "[L]a confraternita dei Fruttajuoli, eretta fino dal 1423, aveva qui un ospizio composto di 19 camere, ed un oratorio sacro a S. Giosafatte. Quest'arte, unita a quella degli Erbajuoli, aveva un altro oratorio dedicato alla medesimo santo presso la chiesa di S. Maria Formosa. I Fruttajuoli col Erbajuoli erano gli eroi della cosi detta festa dei Meloni. Dovendo essi presentare al doge nel mese d'agosto del primo anno del di lui principato un regalo di meloni (poponi), solevano nel giorno determinato raccorsi in Campo di S. Maria Formosa, e per la Merceria, e per la Piazza di S. Marco, preceduti dallo stendardo di S. Nicolò e da trombe, tamburri e mazzieri [mace-bearers], recarsi in corpo a palazzo, portando i poponi in grande ceste infiorate, e sopra argentei bacini. Introdotti nella Sala del Banchetto, complivano il doge per mezo del loro avvocato, poscia gli facevano offrire da due putti un sonetto ed un mazzolino di fiori, e finalmente fra mezzo le grida di Viva il Serenissimo! consegnavano i poponi allo scalco ducale."

[59] We can deduce what stretch of time Toscanella's description covered by considering the musicians' biographies. Of the madrigalists mentioned, Parabosco came to Venice around 1540, Perissone at least by 1544, and Donato by 1545, whereas the minor composer and contralto Londariti was hired into the chapel at San Marco only in 1549 (see Chap. 9 below, n. 4 and passim). By 1557 Parabosco had died. Londariti left the chapel around the same time (see Ongaro, "The Chapel of St. Mark's," pp. 187-88, who dates his departure between 6 April 1556 and 10 December 1558), and Perissone had most likely passed away by 1562 (ibid., p. 165 n. 194 and Document 272).

Giulio dal Pistrino is almost undoubtedly the same as Giulio Abondante, who published five books of lute music (three extant) between 1546 and 1587. See Henry Sybrandy, "Abondante, Giulio," in The New Grove 1:20, and Luigi F. Tagliavini, "Abondante, Giulio," Dizionario biografico degli italiani 1:55-56.

The organists Padovano and Merulo did not enter San Marco until 1552 and 1557, respectively, Merulo having taken Parabosco's place on the latter's death; but Padovano, true to his name, was a Paduan who had long been in the area, and Merulo has been placed in Venice at least as early as 1555. The latest information on these organists has been amassed by Rebecca A. Edwards, "Claudio Merulo: Servant of the State and Musical Entrepreneur in Later Sixteenth-Century Venice" (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1990), to whom I am grateful for sharing various information before her dissertation was filed. On Padovano and his family, see Edwards, p. 94 n. 27. Edwards speculates that since Merulo witnessed a document for Zantani in Venice on 27 November 1555 (p. 214 n. 2) he may have been studying in Venice for some time before 1555, possibly under Parabosco (pp. 269-70). Merulo's close ties with Parabosco can be deduced from the dedication of the latter's Quattro libri delle lettere amorose (Venice, 1607) by the editor Thomaso Porcacchi, who called Merulo "ora molto intrinseco del Parabosco che glie l'haveva lasciate [i.e., le lettere ] in mano avanti la sua morte"; see Edwards, p. I n. I. Edwards also establishes that the printer and bookseller Bolognino Zaltieri, whom Toscanella names as having engaged him to assemble I nomi antichi, e moderni ("diede carico à me in particolare di raccorre . . . i Nomi antichi, & moderni," fol. [2]), was one of Merulo's partners; see Chap. 3 and Chap. 4, pp. 217-18.

[60] The "corona" was probably a reference to the Zantani family heraldry. See Appendix, E, fol. [3].

13.

La eletta di tutta la musica intitolata corona di diversi novamente stampata:

libro primo (Venice, 1569), title page.

Photo courtesy of Musikabteilung der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

14.

La eletta di tutta la musica intitolata corona di diversi novamente

stampata: libro primo (Venice, 1569), dedication from Zuan Iacomo

Zorzi to Antonio Zantani. Photo courtesy of Musikabteilung der

Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

Zantani as the "'padre' of musicians, literati, sculptors, architects, painters, antiquarians . . . [and] all sorts of honored men."

The anthology (or most of it) was apparently printed by about 1558 but not issued until 1569, ten years after the Ferrarese had brought out the Musica nova. It is worth recounting a bit of the well-known story behind the print and its relation to

Willaert's Musica nova,[61] because it tells us a lot about Zantani's character and about the new function Petrarchan tropes and styles assumed in helping to define identity in a thickly populated urban world. Zorzi had secured the original privilege for La eletta in 1556, but Zantani immediately had it transferred to his own name. Apparently he wanted to avoid the vulgar process of procuring the privilege himself, which it was the usual business of printers to do.[62] On 19 January 1557 Zorzi was granted the privilege for the print along with approval to essay a new printing technique. And both were transferred to Zantani on 29 March 1557.[63]

The anthology was obviously hot property from the start. In addition to Willaert's previously unpublished Petrarch settings, it included new works by Willaert's prominent disciples Donato and Perissone.[64] Unlike the Musica nova, La eletta was planned from the outset as an appealing four-voice potpourri. The reader for La eletta's Venetian license summarized its literary contents as "diverse types of poems" such as "canzoni, sonetti, madrigali, sestine, ballate, and so forth . . . treating youthful topics and amorous emotions."[65]

Ironically, this project brought the Cavaliere more lasting notoriety than any of his other ventures. When Zantani planned the publication he undoubtedly intended the settings from the Musica nova to crown it. He probably got hold of them through his connection with Willaert's three protégés, Parabosco, Perissone, and Donato: it was they who, between 1545 and 1553, had published parallel settings imitating those that later became part of Willaert's Musica nova collection and who therefore must have had closest access to them.[66] As it turned out, however, Polissena Pecorina had already sold the whole corpus (or something close to the printed version of it) with sole rights to Prince Alfonso d'Este, who meant to have it published by Gardane in an exclusive complete edition. The news that Zantani's

[61] For a retelling of the story with illuminating new details and copious documentation see Richard J. Agee and Jessie Ann Owens, "La stampa della Musica nova di Willaert," Rivista italiana di musicologia 24 (1989): 219-305. The authors were kind enough to share the article with me in typescript before its publication. Since Agee and Owens publish all of the relevant documents thus far known, I cite their article for documents, including ones first unearthed by others.

[62] Agee and Owens, "La stampa della Musica nova," Document 7, pp. 246-47. The documents directly concerning printing privileges were nearly all first transcribed in Richard J. Agee, "The Privilege and Venetian Music Printing in the Sixteenth Century" (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1982).

[63] Ibid., Documents 9 and 10, pp. 248-49 (originally located by Martin Morell), which mention the use of new characters and staves.