Four—

Crisis

Job

Although Corinth recovered his physical strength within months, he never overcame the long-term consequences of his illness. Forever after he limped when tired, and his left hand no longer obeyed when he tried to perform intricate tasks. His right hand was affected too and trembled severely. Yet this infirmity did not fundamentally interfere with his ability to paint. A film made of Corinth at work on a painting in 1923 shows that his brush grew steady the moment it touched the canvas and was thereby given additional support.[1] An occasional physiognomic oddity and the character of his brushstrokes, which often follow a predominantly diagonal direction from the upper right to the lower left, are the only reminders of his handicap. Rarely, however, do these technical peculiarities diminish the quality of Corinth's paintings and graphics. On the contrary, Corinth eventually achieved a new synthesis of content and form that often endows his late works with great profundity.

Corinth had come face-to-face with death, and in one form or another virtually all his subsequent works bear the mark of this experience. This is true even of the still lifes and landscape paintings to which he devoted more and more energy, sublimating, as it were, the vigor of his earlier work in visions of nature that are splendid in their amplitude but rarely without a touch of pathos. Nor did Corinth's illness impair his creative drive. The years from 1912 to his death in 1925 turned out to be his most productive. Close to five hundred paintings, over eight hundred prints, and scores of watercolors and drawings—in short, more than half of all his works—date from this time.

Initially, the period following the stroke was one of reproach and bitter self-examination. Corinth blamed his excessive drinking for his illness and vowed to give his life a new direction:

My entire life passed before me, a life which in this lonely battle seemed more precious now than when I was young and strong. I was forced to reckon with myself. Job called to me: Gird up thy loins like a man for I will demand of thee, and answer thou me! "Where wast thou when I created thee?" Thus my path was to be illuminated once more. But time seemed so very short.[2]

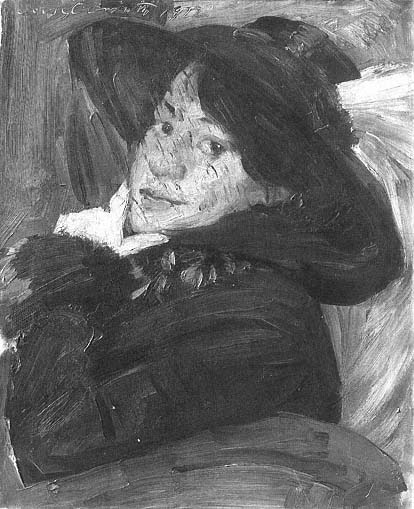

Figure 115

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait , 1912. Oil on canvas, 49 × 36 cm, B.-C. 546. Anna

Held Audette, New Haven, Connecticut.

Photo courtesy Julius S. Held.

While still on his sickbed, Corinth asked for pencil and paper and sketched a series of horrible monsters and strange, ghost-like images of famous figures from history.[3] None of these drawings seems to have survived. Apparently Corinth was unable to resume work in a more premeditated manner until February 1912. Charlotte Berend accompanied him as he returned to his studio for the first time, and she watched as he gazed long into the familiar large mirror.[4] Again and again he moaned in despair. Then suddenly he reached for palette and paint and quickly dashed off the first in a long series of poignant self-portraits that were to focus on his physical frailty and mental anguish (Fig. 115). Sweeping brushstrokes follow the outlines of the coat and hat. In the face the paint is applied in small patches heightened with dabs of white and red that give the skin a peculiar restlessness. Devoid of conventional textural distinction, the face seems in a state of flux. Beneath the broad brim of the hat Corinth's features are smaller and more delicate than in the previous self-portraits. The eyes reflect profound sadness. This is no longer the face of the victorious warrior or of Nietzsche's natural man but rather that of one who has recognized and acknowledges the precariousness of his condition.

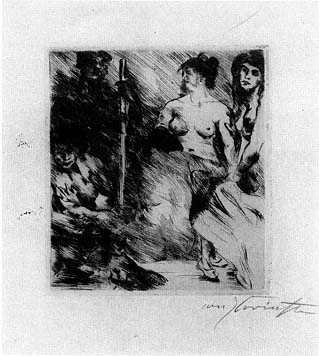

Even when Corinth donned his beloved armor during these weeks, as for instance for the etching The Knight (Fig. 116), the resulting self-portrait differs markedly from the earlier extroversive self-portraits of this type. The helmet now weighs heavily on his head, and neither his posture nor his demeanor fits the assumed role. Corinth portrays himself with etching needle and copper plate, actively pursuing his craft, and in this context the knightly trappings signify his valiant efforts to regain his ability to work.

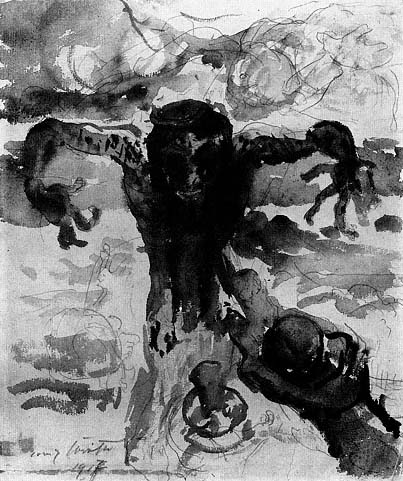

Henceforth Corinth tended to identify more deeply with subjects that center on human suffering, as in Job and His Friends (Fig. 117), a pencil drawing done on tracing paper over a copper plate (Schw. 85) that is one of the earliest surviving works from the time after his stroke. The Old Testament tale of woe no doubt mirrors Corinth's own frame of mind.[5] Indeed, the ill and sorely tested Job of the drawing bears Corinth's features and has draped over his head the same cloth the painter wears in the two costume self-portraits from 1907 (see Fig. 104) and 1909 (B.-C. 400). Job's withered right arm and leg, reversed in the etching for which the drawing was made, allude only too clearly to Corinth's own affliction. Technically, too, the drawing betrays the painter's physical impairment. The lack of conventional modeling sets the drawing apart from the meticulous anatomical studies of the preceding decade. The figures appear flat, and their spatial relation to one another is unclear.

Figure 116

Lovis Corinth, The Knight (Self-

Portrait) , 1912. Etching, 18.0 × 13.8

cm, Schw. 86. Kunsthalle Bremen

(42/127).

Figure 117

Lovis Corinth, Job and His

Friends , 1912. Pencil on

transfer paper, 29.2 × 22.2 cm.

Formerly Allan Frumkin

Gallery, New York; present

whereabouts unknown.

Photo: Horst Uhr.

Charlotte Berend has written of Corinth's anxiety and depression during these months and of his exhaustion following even the slightest physical exertion.[6] Through cheerful encouragement she tried to alleviate his recurrent fears of impending senility, and she aided him as he struggled to summon up his strength. She laid out the colors before him, placed palette and brushes in his encumbered left hand, and removed them from his stiff and swollen fingers when he had finished painting. When his own hand failed to provide adequate support, she gently and tactfully helped to steady his sketchbook.

Several works executed between the end of February and the end of April 1912 document Corinth's efforts to regain full control over the artist's craft. They were done in the small Riviera town of Bordighera, where Charlotte Berend had taken him to spare him the long Berlin winter. In the self-portrait drawing now in Bremen (Fig. 118) Corinth's vacant stare testifies eloquently to the sense of loss and resignation that frequently overcame him at this time. The emphatic contour line encircling the head has been drawn with noticeable strain. The random patches of gray and black barely manage to suggest the texture of hair. Careful modeling has given way to crude hatchings that no longer have any consistent relation to the anatomical structure they are intended to define. The illuminated left side of the face still suggests a fair degree of plasticity, but the opposite side remains flat. The nose is blunted and abnormally elongated, as if the face had gone soft in an irreversible process of dissolution. Corinth's physical and mental state give the laconic inscription "ich" at the lower center of the sheet the character of a poignant confession.

Figure 118

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait , 1912. Pencil,

33.5 × 26.0 cm. Kunsthalle Bremen (1970/158)

Photo: Stickelmann.

Figure 119

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Charlotte Berend ,

1912. Pencil and colored crayons on

cardboard, 46.0 × 37.7 cm. Wallraf-Richartz-

Museum, Cologne (1950/46).

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

The effort it cost Corinth to maintain consistency in the tangible character of a given subject is also seen in a drawing of Charlotte Berend (Fig. 119). The general conception is more ambitious than that of the preceding self-portrait, the nearly full-length seated figure having been placed in a vaguely circumscribed interior space. Diagonal hatchings in the sitter's face continue to define form, but in the rest of the figure they fail to render texture and mass convincingly. Charlotte's dress only seems voluminous; on closer examination it looks lifeless and flat. The lack of plausible anatomical articulation results in a strong sense of compression, as if the figure were cowering in an awkwardly strained posture. Moreover, Charlotte, who had a natural flair for posing, appears ill at ease. She faces her husband, but her eyes evade his gaze. Her acute awareness of the physical and psychological tensions involved in the making of this portrait no doubt accounts for the anxiety she herself projects. A similar air of apprehension pervades the painting Lady with a Fan (B.-C. 517), although here Charlotte's likeness is subordinated to the summary treatment of the individual forms.

Different ambiguities mark the plein air portrait Corinth painted of Charlotte Berend on the balcony of their hotel in Bordighera (Fig. 120). Here the problem is primarily one of pictorial structure. Despite the pronounced diagonal of the balcony railing, the painting essentially lacks perspective, resulting in

Figure 120

Lovis Corinth, On the Balcony in Bordighera , 1912. Oil on canvas,

83.5 × 105.0 cm, B.-C. 540. Museum Folkwang, Essen (241).

abrupt transitions from the figure to the surrounding space. The vertical lines of the hotel's facade do not match, and the building appears to be leaning toward the left. The resulting impression of instability is reinforced by the diagonal shadow that falls across Charlotte's dress and by the position of her parasol, while the intense blue that dominates the color scheme adds an unexpectedly strident tone.[7] In the landscape view at the left, which Corinth recorded a second time in a separate, smaller, canvas (B.-C. 539), the pigments are applied in predominantly parallel strokes that do not convey the varied texture of the terrain. This method of applying the paint is found earlier in subordinate areas of Corinth's works but henceforth came to be employed frequently in other, more dominant, parts of his pictures as well since he evidently found it easier to manipulate the brush in this manner. The slanting brushstrokes further flatten this part of the canvas.

Figure 121

Lovis Corinth, Riviera Flowers , 1912. Oil on canvas,

120 × 100 cm, B.-C. 512. Staatliche Kunstsammlungen

Dresden, Gemäldegalerie Neue Meister (2580 H).

Photo: Deutsche Fotothek.

As if testing his powers of observation, Corinth also turned his attention at this time to an ambitious floral still life (Fig. 121) that in both size and conception rivals the sumptuous floral pieces from the preceding year. The extended inscription, "Lovis Corinth/1. April Bordighera/1912 pinxit," may well indicate that Corinth considered the painting a major work, and the carefully contrived composition reinforces the impression that the painting did not indeed result from an incidental exercise. Seen against a ground divided into four more or less equal components, the flowers occupy the very center of the painting, their shapes echoed in abstracted form by the colors of the table-cloth. The brushstrokes in the flowers are sufficiently controlled so as to render the various species recognizable: calla lilies, roses, tulips, a purple iris, and

Figure 122

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Charlotte Berend , 1912. Oil

on canvas, 59 × 49 cm, B.-C. 519. Staatliche Museen

zu Berlin, National-Galerie (DDR) (957).

sprigs of mimosa and apple blossoms are gathered in a ceramic vase. Yet instead of the élan typical of Corinth's previous floral still lifes, the bouquet conveys an air of restlessness, an impression of struggle. Some of the brushstrokes are notably brittle, negating the delicacy of the textures they are intended to define. And a pronounced suggestion of movement toward the lower right, where the composition remains curiously open-ended as if subject to some inexplicable gravitational force, undermines the viewer's own sense of equilibrium, creating the uncomfortable feeling that the flowers are being swept away.

Corinth's recovery in Bordighera of his ability to communicate a visual impression in a commensurately evocative form is seen in yet another portrait of Charlotte Berend (Fig. 122). The portrait was prompted, as so often in the past, by Charlotte's habit of striking an artful pose, this time with a white fur cape draped casually over her shoulder.[8] The couple had just returned to their hotel room from a ride in the town's annual spring flower parade, and the lingering joy of the shared experience seemingly allowed both painter and

model to dispel the tensions that might otherwise have interfered with the felicitous conception. In this painting Corinth managed to recapture the intimacy that characterizes his earlier portraits of Charlotte. The fashionable dress and hat reinforce her vivacity and charm, while the extreme close-up view allows for a maximum of psychological rapport. Corinth set himself here the challenging task of painting against the light, and any lack of detail follows logically from the strong contrasts in illumination. Only in Charlotte's face, shielded by the brim of her hat and thus less susceptible to the form-dissolving effects of the enveloping light, do the brushstrokes delineate the familiar traits with greater precision.

A similarly successful fusion of content and form can be seen in the small seascape Storm at Capo Sant'Ampeglio (see Plate 21). Corinth had discovered the picturesque promontory during an excursion and was immediately taken by the spectacle of the waves battering the rock-strewn shore. He had by then sufficiently recovered to paint the view under less-than-ideal weather conditions, braving a brisk wind that kept tugging at his easel. According to Charlotte Berend, he painted the picture as in a trance, immersing himself in the experience of the moment.[9] And as so often in the past when his interest was aroused, vision and experience merged in a work that is more than a topographical record. The creative energy unlocked by the painter's empathic response dominates the descriptive details, as swirls of paint slash across the canvas.

Corinth's resurgent self-confidence was profoundly shaken when news reached him from Berlin that Paul Cassirer was circulating the rumor that the painter had become mentally incompetent, that the stroke had left him insane.[10] Although this gossip was malicious, Corinth's illness had prevented him from attending personally to preparations for the 1912 annual exhibition of the Berlin Secession, scheduled to open in early April. Cassirer and Liebermann, therefore, had taken over the responsibility of organizing the show. No doubt in this context Corinth's anxiety about his health acquired a new urgency.

Rivals

Other signs in the German art world were bound to heighten Corinth's concern about resuming his professional life. For as he struggled to recapture the momentum of his career, younger artists, expounding aesthetic principles at variance with his own, were gaining broader public support. The opening exhibition of the New Secession in May 1910 had marked the beginning of a

process that would eventually dislodge the Berlin Secession from the center of modern art in Germany. In 1911 exhibitions of paintings and graphics by the artists of Die Brücke were held at the Berlin gallery of Fritz Gurlitt as well as at galleries in Danzig, Schwerin, Lübeck, Düren, München-Gladbach, and Dresden. The same year the New Secession organized two exhibitions in Berlin, with works by Heckel, Otto Mueller, Pechstein, Schmidt-Rottluff, Kandinsky, Jawlensky, and Nolde. The Brücke painters continued their association with the New Secession until the fall of 1911, when they withdrew, pledging to exhibit henceforth only as a group. By the end of the year they had all settled in Berlin and in the spring of 1912 were again featured at the gallery of Fritz Gurlitt. The Gurlitt exhibition was soon followed by a show at the Commeter Gallery in Hamburg. In Munich, meanwhile, the first Blaue Reiter exhibition opened at the Neue Galerie Thannhauser in December 1911 and subsequently traveled to Berlin and Cologne, while in the Bavarian capital the group mounted a second show at the gallery of Hans Goltz.

In 1910 the Expressionists had found an enterprising champion in the Berlin publisher Herwarth Walden, who featured their drawings and prints in the avant-garde literary weekly Der Sturm and from 1912 on organized at the galleries of Der Sturm a series of pioneering exhibitions that included works by the members of Der Blaue Reiter, Kokoschka, Fauves like Derain and Vlaminck, and leading Cubists and Futurists. In 1912 Walden also published Filippo Tommaso Marinetti's "Manifesto of Futurism" and the more specific "Futurist Painting: Technical Manifesto" as well as an essay by Kandinsky, "The Language of Form and Color," the sixth chapter of the Russian painter's book Concerning the Spiritual in Art . In Cologne Karl Osthaus organized the monumental fourth exhibition of the Düsseldorf Sonderbund, open from May to September 1912. This, the most important German exhibition of modern art ever held, was international in scope and served as a prelude to Herwarth Walden's First German Autumn Salon of the following year, which brought together an impressive collection of paintings and works of sculpture by some ninety artists from fifteen different countries.[11]

The Berlin Secession had never mounted exhibitions of such magnitude and importance. The annual exhibition of 1912 in particular was a lackluster affair. Faced with an unexpected responsibility, Cassirer and Liebermann—who had hardly concerned themselves with the administrative affairs of the association since the debacle of 1910—had too little time to prepare a competitive show. One of their more memorable efforts on behalf of the Secession, however, resulted in Max Pechstein's return to the association. For this Pechstein was expelled from Die Brücke, since he had defied the group's decision to exhibit only jointly.

Figure 123

Lovis Corinth, Before the Mirror , 1912.

Oil on canvas, 140 × 93 cm, B.-C. 533.

Private collection.

Photo: John D. Schiff.

Figure 124

Lovis Corinth, At the Toilet Table ,

1911. Oil on canvas, 120 × 90 cm,

B.-C. 502. Hamburger Kunsthalle,

Hamburg (1857).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

Convalescence

Corinth's health continued to improve rapidly. By the end of April 1912 he was back in Berlin. He spent the summer months in the Bavarian village of Bernried, on the west bank of the Starnberger See, occasionally receiving old friends and other visitors, such as Carl Strathmann, Wilhelm Trübner, and the art historian Georg Biermann, who was then working on his Corinth monograph.

Corinth's work for the remainder of 1912 varies in conception and execution and includes several pieces with which he sought to reestablish continuity with his development prior to the stroke. He completed Paradise (B.-C. 523), a large canvas depicting Adam and Eve surrounded by animals in a verdant landscape. Nearly finished before his illness, this painting apparently required little further work. The interior Before the Mirror (Fig. 123) is a different case. This painting rephrases a picture from 1911 (Fig. 124) showing Charlotte Berend in her boudoir attended by a hairdresser. The later work shows an astonishing change. The high-keyed tones of the earlier painting have given way to colder hues of greater opacity; the fields of color are separated by large areas of black; the brushstrokes have been applied flatly, with little variation in accent or direction. Corinth also modified the composition so as to include himself in the reflection in the mirror, in the act of painting, making this work yet another double portrait of the Corinth couple. But the features of both their faces are so generalized that the two figures appear virtually faceless. This results in a marked psychological distance, especially in comparison with the earlier, erotically charged, double portraits. At the same time there is a new tension in the juxtaposition of Charlotte, who arranges her hair before the mirror, and the painter, who has assumed the role of a distant observer. This juxtaposition is surely not accidental: it is safe to assume that both husband and wife questioned the nature of their future marital life. Charlotte Berend, at least in her later memoirs, ruefully reflects on her age—thirty-one—at the time of Corinth's illness.[12] Corinth was fifty-three. On some occasions, despite her devotion, Charlotte must have rebelled inwardly against the restrictions of life with the aging painter. And as for Corinth, with this painting he concluded the series of double portraits of himself and his wife.

The handsome portrait of Charlotte Berend, now in Nuremberg (Fig. 125), seems to contradict these observations, at least initially, for the extreme close-up view suggests intimacy once again. Yet the elegant clothing, underscored by the white glove and the veiled hat, tends to conceal the sitter, whereas in

Figure 125

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Charlotte Berend , 1912. Oil on canvas, 64 × 50

cm, B.-C. 532. Germanisches Nationalmuseum, Nuremberg (St. Nbg. Gm. 993).

the preceding portrait from Bordighera (see Fig. 122) the dress still accentuates Charlotte's sensuous charm. In no previous portrait—with the possible exception of the drawing from March 1, 1912 (see Fig. 119)—does Charlotte Berend appear so buttoned up. Despite her physical proximity and open gaze, she seems remote, as if she had become for the painter an ideal image inhabiting a world he no longer really shared. And in fact Corinth subsequently painted fewer depictions of Charlotte Berend than during the first nine years of their marriage. Although she is shown anonymously in eight—possibly nine—other paintings (B.-C. 553, 577, 579, 584, 658, 699, 704, 738a, 961), the actual portraits where she is specifically identified number only seven (B.-C. 624, 651, 685, 736, 837, 838, 846), as compared with more than sixty paintings in which she appeared before 1912. Furthermore, in all of these later portraits Corinth's view of his wife is markedly detached. Depending on the painterly technique employed, her features are either blurred or psychologically neutral.

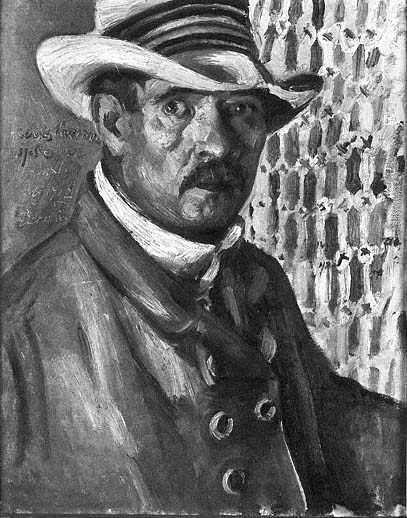

The technique employed in the Nuremberg portrait of Charlotte Berend is also noteworthy. The paint has been applied less erratically than in the works that just precede it. The brushstrokes no longer flicker across the canvas but follow broadly sweeping rhythms that lend clarity to the composition. The result is a new sense of calm, shared by several of Corinth's paintings from the latter half of 1912. In the self-portrait he painted in August at Bernried (Fig. 126) the modeling is firm, and the structural clarity is reinforced by the simple color scheme: the flesh tones and the yellow of the hat are set off against a palette of blue, white, and green. The effect of the high-keyed colors is cheerful. To judge from his appearance, Corinth had made a remarkable recovery. Although his look remains serious, the despair and resignation of the self-portraits from the first half of the year have disappeared. The firm gaze and resolute mouth speak instead of renewed commitment and determination.

But Corinth also continued to reflect deeply on his condition. This is evident from the compelling Samson Blinded (see Plate 22), one of the few figure compositions he painted in 1912. This is a fairly large picture, painted in bold, simplified strokes. A world of difference separates it from Corinth's earlier treatment of the theme (see Fig. 98). The composition from 1907 typifies his extroversive showpieces of foreshortened bodies and complicated postures; the later one is simple, dominated by the single figure of the mutilated hero who blindly gropes through an open door, his hands in chains, his eyes covered with a bloodstained cloth. The shocking immediacy of the portrayal elicits both sympathy and revulsion. As in the drawing of Job (see Fig. 117), Corinth saw in Samson's anguish a "universal human" significance. Samson's

Figure 126

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait in Panama Hat , 1912. Oil on canvas,

66 × 52 cm, B.-C. 515. Kunstmuseum Lucerne.

Photo: Robert Baumann.

Figure 127

Lovis Corinth, Rudolf Rittner as Florian

Geyer , 1912. Oil on canvas, 180 × 170 cm,

B.-C. 521. Formerly in the Collection

of the City of Berlin;

present whereabouts unknown.

Photo: after Bruckmann.

features resemble the painter's own, and the setting is not a biblical reconstruction but a modern domestic interior. Both Job and His Friends and Samson Blinded suggest that Corinth's attitude toward religious subjects had undergone a profound change. No longer satisfied with the mere re-creation of biblical narratives, he had come to subordinate the specific to the generalized and universal. As a result, the content of these works is intensified in a new personal context.

By the end of 1912 Corinth's health had sufficiently improved that he could announce his candidacy for reelection to the presidency of the Berlin Secession. When Paul Cassirer was nominated as well, Corinth withdrew from consideration. Cassirer was elected in December 1912 and, in a gesture of appeasement, offered to mount a major retrospective of Corinth's work at the Secession galleries. This exhibition, held from the end of January to the end of February 1913, featured more than two hundred paintings representing all the major stages of Corinth's development, from his student years in Königsberg to the period following the stroke. In his preface to the catalogue Corinth acknowledged the difficult circumstances under which his latest works had come into being: "My most recent pictures . . . were initially hard to do because of many a fateful affliction, but I hope that I have overcome these impediments, and I intend to continue on my path."[13] The one work that Corinth was unable to obtain for the retrospective was the portrait of Rudolf Rittner in the role of Florian Geyer (see Plate 16), because the owner of the painting refused to part with it.[14] The refusal upset Corinth immensely until Cassirer suggested that he paint the picture a second time from memory.[15] The second version (Fig. 127), with virtually the same dimensions as the first, is both

Figure 128

Lovis Corinth, Bowling Alley ,

1913. Oil on canvas, 83.2 × 61.0 cm,

B.-C. XI. Niedersächsisches

Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie,

Hannover (KM 140/1949).

simpler and more expressive. The brushstrokes, far from serving textural distinctions, define the image only broadly. There is also less concern for anatomical plausibility, and the fierceness of Hauptmann's embattled hero has been intensified almost to the point of caricature. In his determination to include a picture of Florian Geyer in the exhibition, Corinth was clearly motivated less by a desire to demonstrate his undiminished skill as a portraitist than by his personal identification with the leader of the Peasants' Rebellion. Corinth in fact used the image of Florian Geyer for the color lithograph he prepared as a poster for the exhibition.

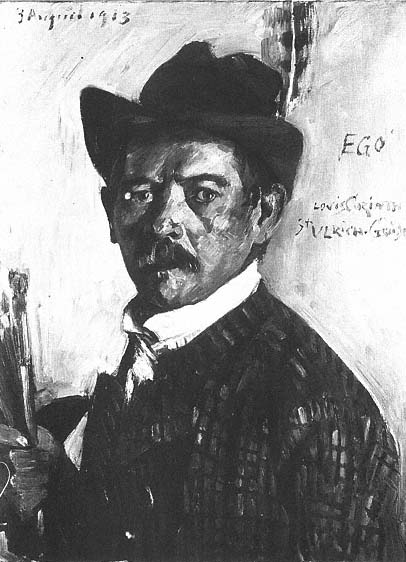

During 1913 Corinth traveled extensively. In March Charlotte Berend accompanied him again to the Riviera, this time to the French resorts of Menton and Beaulieu. In April he spent several days in Düsseldorf and Mannheim in connection with an exhibition of his works there that followed the large retrospective in Berlin. In July and August he vacationed with his family in the Tyrolean hamlet of Sankt Ulrich and spent most of September at Klein-Niendorf, in the Baltic Sea province of Mecklenburg. The itinerary alone suggests that he had fairly well recovered. But his works from that year remain uneven in quality and often betray a continuing struggle. In the painting of an outdoor bowling alley, for instance (Fig. 128), done at Klein-Niendorf, the opacity of the saturated hues and the systematic brushstrokes deprive the landscape of its atmospheric character and depth. The Self-Portrait with Tyrolean Hat (Fig. 129), in contrast, from Sankt Ulrich, indicates both greater technical control and superior conception. Everything about the painting suggests energy: Corinth's firm grasp of the brushes, the determined expression, the resolute turn of the head. The jaunty hat even adds a touch of frivolity to the portrayal. All this is underscored by the affirmatory "Ego" of the inscription.

Figure 129

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait with Tyrolean Hat , 1913. Oil on canvas,

80.5 × 60.0 cm, B.-C. 586. Museum Folkwang, Essen (356).

New Troubles in the Berlin Secession

In some respects Corinth's professional battle had just begun. Recognizing that the Berlin Secession had to compete with many new galleries and artists' associations, Paul Cassirer moved quickly to instill in the organization a more enterprising spirit. He mobilized the group's progressive forces by enlarging the executive committee and adding a new committee in charge of exhibitions, chairing both committees himself. From an artistic point of view the annual exhibition of the Berlin Secession in 1913 more than justified Cassirer's autocratic methods. It was an impressive show that offered a broad overview of the genesis and development of modern art. Featured among the pioneers of the modern movement were Cézanne, van Gogh, Seurat, and Toulouse-Lautrec. The younger generation of foreign painters was represented by the Fauves, including Matisse, Derain, van Dongen, Friesz, Marquet, and Vlaminck. Liebermann and Trübner were each given an entire room. Another room, dominated by Matisse's large canvas Dance (1910; Hermitage, Leningrad) was set aside for German sculptors, among them Barlach, Lehmbruck, and Georg Kolbe. Also on exhibit were paintings by Kokoschka, Beckmann, Christian Rohlfs, and former members of Die Brücke, the group having only recently disbanded.

Not everyone was happy with the exhibition, however. Thirteen members of the Berlin Secession whose entries had been rejected claimed that they had been sacrificed to Cassirer's desire to gain control of the organization. They accused him, as well as Liebermann and the three jurors of the show—Max Slevogt, Käthe Kollwitz, and Louis Touaillon—of duplicity and proceeded to exhibit their works independently in a rented shop not far from the Secession galleries. At a specially convened general meeting Slevogt demanded that the thirteen leave the organization. When they refused, Slevogt, Liebermann, Cassirer, and thirty-nine others resigned instead, including Beckmann, Kollwitz, and Barlach. Corinth, however, whose relationship with Paul Cassirer had been strained for some time, stayed with the thirteen malcontents, even though, artistically speaking, they were hardly a match for those who had resigned. Karl Scheffler noted the irony of this development: "It was a grotesque situation: those who remained legally constituted the Secession, whose ideals—since they were less talented—they were unable to uphold, while those who resigned embodied the group's spirit, even though they could no longer claim to be members of the Berlin Secession."[16]

Corinth was elected president of what was henceforth known as the Rump Secession, and he retained this office until his death. Since the building used by the Berlin Secession on the Kurfürstendamm was legally owned by a cor-

poration headed by Paul Cassirer, the Rump Secession lost its exhibition space. Not until 1915 did the organization acquire a new building, also on the Kurfürstendamm, but the Rump Secession was never strong enough to develop a vigorous exhibition policy. It had little impact on developments in German art and was finally dissolved in 1932. Those who had resigned from the Secession fared much better, at least initially. In the autumn of 1913 they sponsored an exhibition that featured works by Munch, Picasso, and the Expressionists. In 1914 they founded the Free Secession, with Liebermann as honorary president, and marked the event with an exhibition that included Liebermann, Beckmann, Slevogt, and the former members of Die Brücke as well as Feininger, Karl Hofer, Ludwig Meidner, Max Oppenheimer, Hans Purrmann, and Corinth's former student Oskar Moll. Among the sculptors were Barlach, Lehmbruck, and Kolbe. Exhibiting as guests were Auguste Rodin, Ferdinand Hodler, Adolf von Hildebrand, Ernesto de Fiori, Aristide Maillol, Gerhard Marcks, and René Sintenis. Cassirer, unwilling to continue as business manager, played only a marginal role in the new association, and without his support the Free Secession never achieved the financial success of the old Berlin Secession. Nonetheless, the Free Secession remained a strong force in German cultural life. When the activities of the group ceased at the height of the postwar inflation in 1923, the membership stood at 144—including the country's leading painters, sculptors, and graphic artists.[17]

Credo

What compelled Corinth to side with a group of minor artists? Was it loyalty? Sheer bullheadedness fostered by bad feelings between him and Cassirer? Or was it the need, as a new generation of artists was announcing ever more vociferously the end of an era, to affirm his faith in the tradition out of which he had developed? A case can be made for the latter supposition, for Corinth himself had said this much in the catalogue to the retrospective of 1913: "Just as in the history of art the present is built upon the past, I am going to remain faithful to my heritage."[18] In the preface to the same catalogue he had made a further point of distancing himself from the avant-garde: "Even if today new developments manifest themselves, I cannot, just to remain modern, change my conviction so that I can be given a designation whose desirability I find questionable."[19]

In the context of Corinth's illness and the subsequent quarrels in the ranks of the Berlin Secession, his hostility toward the avant-garde—first manifested

in his 1910 article in Pan —does indeed take on a new dimension. Corinth's need to rebuild his career in the tradition he knew best does not make his intolerance any more defensible, but it accounts for the urgency with which he sought to justify his position. His need to safeguard the basis of his art at a moment of great personal vulnerability both modifies and explains his attacks on artists, especially those who had strayed from a quintessentially European tradition.

Corinth's strongest disdain for their work as well as his strongest defense of the principles he stood for is contained in an address he gave before the Free Student Association of Berlin in January 1914.[20] This address is both a warning against imitating modern trends from abroad and a plea to respect the old masters. In it Corinth laments the adoption by many young German painters of Cubism and its various offshoots, whose pictorial laws led them to sacrifice their individuality: "I would be delighted if our time would bring forth someone who with one kick of his foot would turn these mathematical tricks upside down."

Matisse and his followers do not fare much better. Corinth accuses Matisse of having turned the "sensitive, awkward . . . expression" of tribal art into a "fad." Commenting on the "impossible anatomical constructions" of the nudes in Matisse's Dance , the painting that had hung in the last exhibition of the old Berlin Secession, he asserts that even "the boldest fantasies of an African craftsman could not have produced a greater caricature of the naked European man or woman." Referring within a larger context to the great popularity of Matisse's studio, Corinth says facetiously of his own former student Oskar Moll, who in 1907 had gone to Paris to study with the French painter: "It was a miracle: to the amazement of all who knew him, he returned after hardly more than three months totally transformed. He left as a blond, fair-skinned Allemand and came back as a Congo Negro; in his portfolio there were but a few studies of curves that looked as if they had been drawn by Negro youths."

The Italian Futurists' insistence that artists turn away from the past and from conventional methods provoke Corinth's bitterest scorn. After quoting extensively from various Futurist articles that had appeared in the magazine Lacerba , he suggests that these artists ought not to be allowed to exhibit, since by their own admission they were not to be taken seriously.

Early in the address Corinth defines the term modern as it relates to art. Modern paintings are those that have retained their freshness through the centuries—the work of Rembrandt, Frans Hals, and Velázquez, for example. Paintings produced solely in response to contemporary trends are nothing

more than Modebilder , "fashionable" pictures, bound in time to lose their interest and appeal. Corinth concludes by calling the students' attention to the specifically German tradition of Grünewald, Dürer, and Holbein, emphasizing the need for solid training as a safeguard against the temptation to follow and to imitate.

It is necessary to set for the young student . . . the highest goal and to allow him to reach this goal [only] through untiring industry and the most determined willpower. If he is trained in all aspects of his craft and sufficiently grounded in all the fundamentals, the student will no longer be impressed by anything foreign and will rarely be tempted by the wish: I, too, would like to do that. Because he follows a different goal: to fulfill himself and to develop his own personality. . . . We must have the highest esteem for the masters of the past. . . . Whoever does not honor the past has no hopeful prospects for the future, and it would be better were such a person to take a millstone and go where the water is deepest.

Corinth felt strongly enough about these views to publish the speech in pamphlet form[21] and also summarized his main points in a short article in the Berliner Tageblatt .[22] Conceived as a "summons to young people," this article condemns once more the readiness of his younger contemporaries to sacrifice art to what he considered short-lived fads. Stating that without an understanding of the old masters artists can achieve neither "self-knowledge" nor "self-conquest," he accuses the new generation of scorning the study of nature and expresses the hope that someday discipline and hard work will again replace "frivolous license."

Corinth returned to these thoughts in his autobiography in the autumn of 1914, moved in part by feelings of patriotism at the beginning of the First World War.[23] The tendency of young German painters to neglect the old masters in favor of the faddish imitation of the "naïveté of exotic wild men" seemed to him a "virtual epidemic" that had originated in France among artists of French, Spanish, and Balkan origins, and he warns against the leveling effect of this "Franco-Slavic international art." He disdains the last exhibition of the old Berlin Secession as a "witches' sabbath," where despite the large number of works shown, there was so much emphasis on similar pictorial methods that the paintings looked as if they had all come from the same studio.

In defending the study of nature and the old masters Corinth implicitly defends his own artistic tools and the principles he had espoused for years. Indeed, if Corinth expresses anything like a credo, he does so in his address

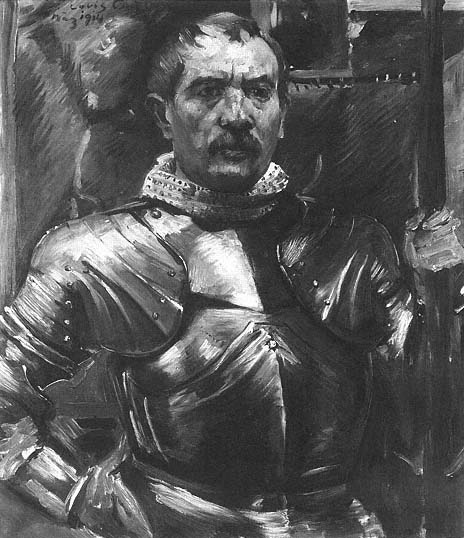

Figure 130

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait in Armor , 1914. Oil on canvas, 100 × 85 cm, B.-C. 621.

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1964).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

to the Berlin art students. That he was not really hostile to foreign art is evident from his own development. Yet he did not share the view, common among the avant-garde, that to create something new, the artist must destroy the old. On the contrary, Corinth had a keen sense of history and saw himself as a link in a chain encompassing both German and non-German sources. But he was also an individualist who believed that an artist's individuality lay in the way he transformed tradition without abandoning it. Corinth's own work—as Hilton Kramer once observed—is like a "hinge on which a rich inheritance undergoes a profound metamorphosis into the peculiar stringencies of the modern era."[24]Self-knowledge and self-conquest were Corinth's words for the process, and at no time in his career did he feel a greater need to defend what they stood for than during the years that immediately followed his illness.

The self-portrait of March 1914 (Fig. 130) is more or less contemporary with Corinth's "summons to young people." Yet if the picture was intended to conjure up a commensurately martial air, the results are not convincing. The posture recalls the cocky stance of earlier self-portraits in armor (see Figs. 105, 106), but as in the etching from 1912 (see Fig. 116), the painter's expression fails to support the role. The hard, gleaming metal contrasts sharply with the texture of the skin, and as if to soften the pressure of the armor, Corinth has wound a scarf around his neck, isolating the head both physically and psychologically—an impression reinforced by the probing gaze. It is as if Corinth had begun to recognize the absurdity of the costume, as if he were becoming dimly aware that he could not develop further without accepting new premises.[25]

The Genesis of a New "Expressionism"

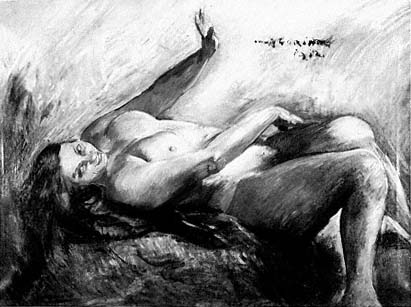

During the years 1913–1914 Corinth's pictorial conception began to undergo profound changes. As if to prove to himself that he could still handle even the most physically challenging assignment, he executed at this time a set of wall decorations for the Villa Katzenellenbogen, at Freienhagen, near Berlin, comprising ten large tempera paintings on canvas (B.-C. 567, 568, 571, 573, 609–614) illustrating episodes and individual figures from Homer and Ariosto. In these paintings, as well as in the preliminary drawings he made for the project, he continued to strive for anatomical accuracy and complicated fore-shortened postures. Similar in conception and execution are several contemporary paintings of the female nude (B.-C. 561, 562, 564, 566) as well as the

Figure 131

Lovis Corinth, Potiphar's Wife , 1914. Oil on canvas, 107 × 148 cm, B.-C.

605. Hessisches Landesmuseum Darmstadt

(on loan from a private collection).

composition Ariadne on the Island of Naxos (B.-C. 569). The two versions of Joseph and Potiphar's Wife (B.-C. 606, 607) from 1914, in contrast, announce a different approach. In the preparatory painting in Darmstadt (Fig. 131) only Potiphar's wife is shown, reclining in an attitude of physical abandon. The brushstrokes, while simplified, emphasize the voluptuous forms of the anatomy; the heroine's lascivious gaze makes the viewer an unwitting accomplice in her amorous pursuit. In the two finished versions, of which the one in Krefeld may serve as a representative example (Fig. 132), the explicit eroticism of the subject has been subordinated to a much freer execution. The brushstrokes cascade downward from the upper right to the lower left, creating a suggestive rather than a descriptive ambience. Although the facial expressions and the anatomy of the nude are overspecific, even these exaggerations become bearable with the otherwise sketchy application of paint.

There is evidence that Corinth's drawings played an important role in his gradual acceptance of a language of form far less dependent on observation and description than heretofore. In one of the preliminary drawings for Sam -

Figure 132

Lovis Corinth, Joseph and Potiphar's Wife , 1914.

Oil on canvas, 77 × 62 cm, B.-C. 607. Kaiser

Wilhelm Museum, Krefeld.

son Blinded (Fig. 133), inscribed incorrectly in the lower right corner with the year 1913, Corinth heightened the expressive content by subjecting the anatomy to violent dislocations. The contours are not carefully controlled but torn. The widely spaced diagonal shading, freed from the necessity of modeling, respects the surface character of the sheet. Corinth did not apply the same simplified approach to the painting itself, however, but limited such formal explorations to the graphic medium.

In Ecce Homo (Fig. 134), a 1913 drawing in lithographic crayon and watercolor, description is subordinated still further to suggestion. The web of diaphanous lines is given only slight definition by the colored wash; and since neither setting nor groundline is indicated, the image rises mysteriously into the pictorial space. Unlike conventional representations of the subject, which usually objectify the episode entirely within the confines of the picture, Corinth's drawing forces the viewer into a real dialogue with the figures shown because it is the viewer whom Pilate addresses with his questioning gesture.

Figure 133

Lovis Corinth, Samson Blinded ,

1912. Crayon, 46.6 × 34.0 cm,

Staatliche Museen, Berlin (DDR)

(25/7826).

Figure 134

Lovis Corinth, Ecce Homo , 1913. Pencil and

watercolor, 33.7 × 25.4 cm, Eidgenössische

Technische Hochschule, Zurich.

Figure 135

Lovis Corinth, The Carrying of the Cross , 1916. Pencil,

25 × 35 cm, Kunsthaus Zurich (1935/25).

Photo: Walter Drayer.

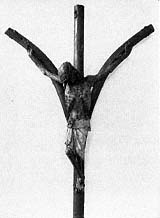

Figure 136

Lovis Corinth, Crucified Christ , 1917. Pencil and watercolor, 33.5 × 28.5 cm.

Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich (G 15.679).

Figure 137

Anonymous German, Plague

Crucifix, early 14th century.

St. Maria im Kapitol, Cologne.

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

There can be no doubt that Ecce Homo is yet another work steeped in Corinth's personal experience, part of his continuing effort to mythologize the events of his life in paradigmatic literary subjects. This personal component accounts for much of the drawing's formal audacity and meaning. Moreover, it was conceived as an independent work, not as a study for some painting or print. Among Corinth's paintings only two figure compositions suggest that he was prepared as early as 1913 to accept a comparatively sketchy execution as a "finished" work in that medium as well. One is the anecdotal Christmas Eve (B.-C. 577), a painting of Charlotte Berend in the disguise of Santa Claus presenting gifts to the Corinth children; the other is the so-called Small Martyrdom (B.-C. 558), which Corinth had begun in 1908 with the aid of a model strapped to a custom-made cross. In 1913, having added the figures of Mary, Longinus, and an executioner, he decided to sign the canvas, although it still retained the appearance of a preliminary oil sketch.

Corinth's development as a draftsman was not as consistent, however, as the above examples suggest. Indeed, in many drawings he reverted to his earlier academic conception. Not until 1916 did he explore more fully the departure from nature and the expressive handling of the graphic medium that distinguish the drawings Samson Blinded and Ecce Homo . The frieze-like composition of The Carrying of the Cross (Fig. 135) harks back to Martin Schongauer's famous print. But even though the architectural setting allows the drawing to be understood in terms of depth, real space has collapsed. The arch of the city gate in the upper left and the crosses of Christ and the two thieves are merely suggested by overlapping amorphous shapes that occupy the same plane. The contours of the figures have been negated by the blurring effect of the superimposed shading. Surface has begun to replace line; mass has been reduced to tone.

Corinth's development as a draftsman culminates in the watercolor drawing Crucified Christ (Fig. 136) of 1917. Here the horrid figure of Christ rises to the picture surface like a specter, virtually undefined in texture and mass. As in the Ecce Homo , the proximity of the frame propels the image into the viewer's space and consciousness. Removed from a larger narrative context, like the terrifying German plague crucifixes from the fourteenth century (Fig. 137), this Crucified Christ is the very incarnation of physical and psychic pain.

Without completely abandoning his faith in visual experience, Corinth openly renounced the academic ideals of his student years and earlier career when he wrote in October 1917 to the editor of Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration : "The hastiest sketch done before nature has greater artistic value than the most conscientiously painted composition pieced together in the studio."[26]

That Corinth's development as a draftsman had brought him to this recognition is evident not only from the drawings themselves but also from their new importance in his work. By 1916 there is little difference in form or conception between a drawing such as The Carrying of the Cross and the two lithographs (Schw. L245, L246) and the etching (Schw. 263) for which the drawing was a preliminary study. Still more striking is the evolving reversal in the relationship of Corinth's drawings to his paintings. His earlier drawings were subordinated to the paintings, serving generally as preparatory sketches. And even when conceived as independent works, they never seriously challenged the prodigious output of his brush. From 1914 on, however, he sought to impart the expressive force of his drawings to his painting as well—though not yet to new works; instead he subjected earlier paintings to the dynamics of his new drawing style by turning paintings into prints. Earlier he had made etchings after a number of his paintings, but always with the intent of reproducing the originals fairly closely. Not until his drawing style had matured did he begin to impose the same expressive simplifications on the graphic repetitions of earlier paintings. Compositions such as Harem (see Fig. 94) and Susanna and the Elders (B.-C. 387), both typical examples of Corinth's earlier extroversive manner, were among the first of his paintings to be so recast (Fig. 138).[27]

Not surprisingly, Corinth's development as a draftsman is closely linked to his growing skill as an illustrator. His earliest illustrations, a series of marginal vignettes and full-page drawings for Joseph Ruederer's collection of short stories, Tragikomödien , were done in 1896. They were carefully prepared after many studies of the live model. He did not undertake his next illustrations until 1910, when Paul Cassirer commissioned him to execute twenty-two color lithographs for The Book of Judith (Schw. L54). These, as well as the twenty-six color lithographs for The Song of Songs (Schw. L82) from the following year, are still not true illustrations but are more akin to small-scale history paintings, rivaling rather than enhancing the text. They too are based on a large number of preliminary studies and, like Corinth's paintings at this time, emphasize complicated postures and a strong sense of plasticity. In these respects they differ sharply from contemporary illustrations by Max Slevogt, whose imagination took flight without the aid of a model. Slevogt's activity as an illustrator began on a large scale much earlier than Corinth's. His nearly 150 pen-and-ink drawings for Ali Baba , of which forty-four were published by Bruno Cassirer in 1903, are lively improvisations that blend, rather than compete, with the text, prodding the reader's imagination at every turn of the page. Corinth first achieved a comparable degree of spontaneity in 1913 with his

Figure 138

Lovis Corinth, Harem , 1914. Etching, 18.1 × 16.4 cm, Schw.

170. Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich.

Figure 139

Lovis Corinth, Count Durande and Francoeur ,

from Achim von Arnim, Der Tolle Invalide auf

Fort Ratonneau , 1916. Lithograph, 45.5 × 30.2 cm,

Schw. L269 V. Staatliche Graphische

Sammlung, Munich.

lithographs for episodes from The Thousand and One Nights (Schw. L140) and for "Le Connestable" (Schw. L143), a story from Balzac's Contes drolatiques . His real breakthrough as an illustrator, however, came in 1916 with the lithographs for Achim von Arnim's Der Tolle Invalide auf Fort Ratonneau (Fig. 139): these no longer look like individually framed pictures but appear to grow organically from the pages of the book.

Perhaps a renewed awareness of Max Klinger's views on the freer relation of the graphic arts to the world of nature helped to change the position of the drawings in Corinth's work,[28] for his paintings continued to show a similarly expressive distance from nature only sporadically. A third version of Joseph and Potiphar's Wife in 1915, for example, was cast in a deliberately controlled form (B.-C. 657). Only in 1917 do Corinth's paintings also begin to show a more consistent use of evocative color and form and a diminished reliance on pure observation.

The stylistic evolution of Corinth's late work is most readily documented in the numerous still lifes he painted beginning in 1912. As in the example from Bordighera (see Fig. 121), he initially aimed for sumptuous effects, with showy flowers in expensive vases, often juxtaposed with bowls of rare fruit and confections. The earliest examples still show the environmental context of the various objects, but beginning in 1915 (Fig. 140) space is increasingly neglected, and the objects are usually observed from above, so that they appear more randomly distributed across the surface of the canvas. Although the pears and apples in the Schweinfurt painting are modeled, the other elements of the still life lack textural distinction. Even the statuette at the upper right has little representational value and functions primarily as part of the pictorial structure. The colors, on the whole, are somber, and black has been used profusely in both the shadows and the ground. More genial in expression is the still life from 1916 (Fig. 141). As in the preceding painting, the downward view flattens the imagery, and black is again a major feature in the composition, although its effect is lightened by the cheerful hues of the Chinese figurine, the darkly glowing red of the lobsters, and the shades of white and blue that flash across the table cloth.

The evocative Still Life with Lilacs (see Plate 23), painted in 1917, helps to explain Corinth's new way of seeing nature. In it the tangible image, perhaps more overtly than ever before, was largely a pretext for revealing—in the process of painting itself—the inner meaning of the picture. In that sense Corinth approached the subject exactly like the Expressionists, who similarly were less concerned with resemblance than with artistic vision and who sought

Figure 140

Lovis Corinth, Still Life with Fruit , 1915. Oil on canvas,

55.5 × 70.5 cm, B.-C. 644. Sammlung Georg Schäfer,

Schweinfurt.

Figure 141

Lovis Corinth, Still Life with Buddha, Lobster, and Oysters , 1916.

Oil on canvas, 55 × 88 cm, B.-C. 664. Galerie G. Paffrath, Düsseldorf.

to penetrate appearances to lay bare the inner essence of things. The flowers are dissolved in a torrent of brushstrokes that follow the familiar diagonal direction from upper right to lower left. The entire surface of the canvas vibrates, producing an impression of restlessness and excitement that unifies the picture but does not allow the eye to focus on any specific detail. Light from the upper right falls on the flowers yet scarcely penetrates beyond the uppermost blossoms of the bouquet. Except for a few touches of bright red, green, and white, the flowers remain in darkness, as shades of somber green and purple are enveloped in strokes of deep black. Beneath the painting's blustering vigor one senses a profound disquietude and an awareness that decay eventually embraces all living things. Prodigiously wasteful in their splendor, the lilacs seem consumed from within and thus take on the character of a metaphoric image into which the painter projected the knowledge of his own physical frailty.

In his portraits, too—again more or less consistently only from 1917 on—Corinth adopted a similarly expressive pictorial structure. Most of these works (commissioned portraits are the exception among them) depict members of the painter's family and friends; and this private character most likely encouraged the greater freedom in conception and execution. Initially Corinth continues to emphasize verisimilitude, but optical truth yields increasingly to subjective interpretation. This is apparent even in the portrait of Wilhelmine from 1915 (Fig. 142), in which Corinth projected his own psychological disposition onto his daughter, then only six years old. The window, through which no light penetrates, and the back of the chair, echoing the posture of the girl's arms, enclose her and restrict her movement. Amid the vivid touches of color, the face, surmounted by the broad-brimmed hat, remains a center of calm. And only the face has been given definition; the rest of the body is simplified. This pictorial isolation of the girl's features also underscores her solitude. Gazing at the viewer with large, pensive eyes, she has no real contact with the toy she holds. Of the children's portraits of the modern period only Edvard Munch's famous painting Puberty conveys a more poignant impression of loneliness, although in the very different context of explicitly adolescent anxieties.[29]

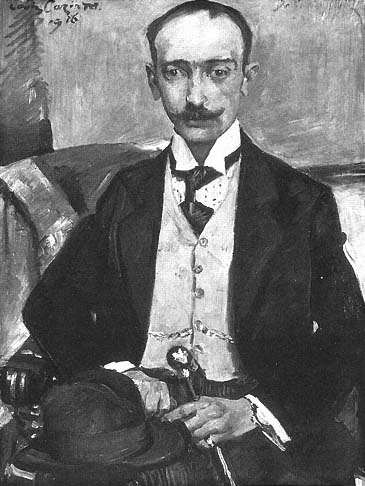

A more conventional conception governs the portrait of Karl Schwarz (Fig. 143) from 1916. Schwarz is seated quietly, his hat on his knee, his left hand clutching a walking cane. Corinth clearly did not record the sitter's fastidious appearance without a touch of irony. At the same time, he was sensitive to the sitter's inner life. Karl Schwarz averts his gaze, but the feverish glow of

Figure 142

Lovis Corinth, Wilhelmine with a Ball , 1915. Oil on canvas,

95 × 72 cm, B.-C. 652. Landesmuseum Oldenburg (LMO 13.328).

the eyes belies the placid demeanor, while the fashionable suit and accessories emphasize his frailty. Karl Schwarz (1885–1962) lived indeed in a constant state of delicate health. Employed as a reader for the publishing house of Fritz Gurlitt, he was completing his oeuvre catalogue of Corinth's graphics at the time of the portrait. The Milwaukee portrait itself originated in the context of this work, as did a second, more simplified but anecdotal, portrait from the same year, now in Aachen (B.-C. 666), which depicts Schwarz in the process of examining one of Corinth's portfolios.[30]

Figure 143

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Dr. Karl Schwarz , 1916. Oil on canvas,

104.9 × 80.0 cm, B.-C. 667. Milwaukee Art Museum Collection

(Gift of Thomas Corinth).

Photo: P. Richard Eells.

Figure 144

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Otto Winter , 1916. Oil

on canvas, 90.6 × 61.2 cm, B.-C. 668. Niedersächsisches

Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, Hannover (KM 23/1950).

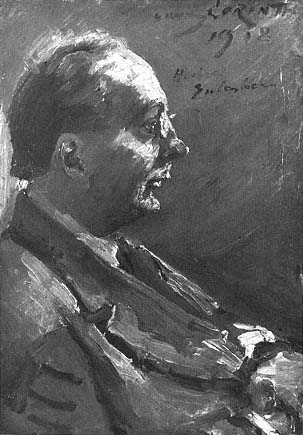

The range of expressive possibilities that Corinth could summon up by 1916 is illustrated by his portrait of the Hannover pharmacist Otto Winter (b. 1855) (Fig. 144), an avid collector who owned several paintings by Corinth as well as works by the Expressionists, such as Kokoschka's famous 1914 allegory The Tempest (now in the Kunstmuseum, Basel). Although Corinth made Winter's head more prominent than his hands and torso, he nonetheless subordinated the facial features to the general effect. The sitter's expression is kindly, benevolent—in sharp contrast to the ominous picture ground, pervaded by an unpleasant sulfurous yellow. Furthermore, any sense of stability and emo-

Figure 145

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Herbert Eulenberg , 1918. Oil

on canvas on panel, 71 × 50 cm, B.-C. 732. Kunstmuseum

Düsseldorf (M 5307).

Photo: Landschaftsverband Rheinland/

Landesbildstelle Rheinland.

tional assurance is undermined by the labile character of the pictorial structure. The asymmetrical placement of the figure and the gravitational pull effected by the slashing brushstrokes introduce an element of transience that in one way or another informs all of Corinth's subsequent portraits. In the portrait of Herbert Eulenberg (1876–1949) (Fig. 145), for example, the writer who in 1917 published a short pamphlet on Corinth,[31] all the forms have become fluid. As if destroyed from within, the skin appears broken, and the darkest values of the yellowish ocher tonality that dominates the portrait seem to ooze through to the surface.[32]

War

Corinth's increasing pessimism, originally induced by his illness, was further nurtured by the cataclysmic events of the First World War, which he witnessed, though from a distance, with profound anxiety. His initial response to the outbreak of the war was, like that of many Germans, one of patriotic fervor. "Each German considers himself the special protector of the German hearth," he wrote at the outbreak of the war, evoking the memory of Bismarck, Blücher, and Luther. "The German Empire was resurrected anew through blood and iron in 1871, and the one who created Germany is one of the greatest men of our dear fatherland."[33] He spoke of the "courage" with which the "frivolous games" of the enemy were being warded off and of the "furor teutonicus" that would soon demonstrate to the world that peace in Germany was not to be disturbed with impunity.[34] He was deeply distressed by the Russian invasion of East Prussia in late August 1914 and by the subsequent devastation of many villages and towns, including Tapiau, where his painting Entombment (see Fig. 95) was destroyed in an attack on the city hall. It was in this general context that he referred to the war as a "Holy War."[35] Thomas Mann, incidentally, expressed his own patriotic sentiments in similar terms when early in the war he summoned his fellow Germans to recall the courageous example of Frederick the Great. Drawing a parallel between the coalition formed against Prussia in 1756, after Frederick had invaded Saxony in the name of self-defense, and the coalition formed against Germany in 1914, after the Germans had moved into Belgium with the same excuse, Mann wrote: "Today, Germany is Frederick the Great; . . . his soul . . . has reawakened in us."[36]

Corinth's most extensive pictorial response to the war is found in his graphics. During the initial and most volatile phase of the conflict he turned repeatedly to prototypical themes of aggression and combat: warriors attacking defenseless women or protecting them; knights engaged in battle or preparing for war. The subjects of Florian Geyer (see Plate 16, Fig. 127) and The Victor (see Fig. 105) also reappeared in 1914 (Schw. 171, 173), as did characters from other earlier paintings, although in a more generalized form to suit the new context. From The Fight between Penelope's Suitors and Odysseus (B.-C. 571), for example, one of the temperas for the Villa Katzenellenbogen, Corinth selected several figures, divesting them of their original identity to achieve a more universal meaning (Fig. 146). Other themes include the prototypical warrior Saint George (Schw. 187) and Joan of Arc (Fig. 147). The latter, too, was updated to reflect the new war. Although the heroine retains her medieval

Figure 146

Lovis Corinth, Warriors (Odysseus and the

Suitors ), 1914. Etching, 25.7 × 18.5 cm, Schw.

172. Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich.

Figure 147

Lovis Corinth, Joan of Arc , 1914.

Etching and drypoint, 24.4 × 19.4 cm,

Schw. 188. Orlando Cedrino, Munich.

Figure 148

Lovis Corinth, "Barbarians": Immanuel Kant ,

1915. Lithograph, c. 28.5 × 20.0 cm, Schw.

L207. Kunsthalle Bremen (40/563).

armor, among the combatants are a German and a French soldier in modern uniform, and the year 1914 is prominently inscribed inside a glory of light at the top of the composition.

Corinth repeated both the Joan of Arc and the Florian Geyer in 1915 (Schw. L201, L202) for one of the Krieg und Kunst series, portfolios of original lithographs published under the auspices of the Berlin Secession in support of the war effort. Other lithographs by Corinth from that year for Krieg und Kunst include Cain (Schw. L208) and portrayals of such German political and cultural heroes as Bismarck (Schw. L212) and Immanuel Kant (Fig. 148). The latter depicts the Königsberg philosopher looking down on his native city and includes in the title the word Barbarians in allusion to the recent invasion of East Prussia. Kant was not only dear to Corinth as a fellow East Prussian but also widely appreciated at the time for such "Germanic" qualities as his blond hair and steadfast, manly character. Like Johann Gottlieb Fichte, whose reputation was being cultivated anew by the Fichte Society founded at the outbreak of the war, Kant was seen as a fighter for the worldwide cultural mission of the German people.[37]

Figure 149

Lovis Corinth, Artist and Death II , 1916.

Etching, 18.0 × 12.4 cm, Schw. 239.

Kunsthalle Bremen (42/119).

The patriotic sentiment of Corinth's graphics was echoed many times over by other German artists, in Krieg und Kunst and in such wartime broadsheets as Kriegszeit and Künstlerflugblätter , both published by Paul Cassirer.[38] For Kriegszeit Ernst Barlach, for example, produced in 1914 the lithograph Holy War , based on his famous sculpture Avenger from the same year; other contributions by Barlach with such titles as First Victory Then Peace and Heavy Attack suggest the same pugnacious tone.

As the war progressed, Corinth grew increasingly distraught. The thought of death dominates two etchings from 1916 that show Corinth himself at work. In one of them (Fig. 149) he is virtually hemmed in by the human skeleton, familiar from the self-portrait in Munich (see Plate 9), and the skull of a ram attached to the back wall of the studio. In the second etching (Schw. 238) Corinth has turned away from his mirror image and sadly contemplates the macabre prop. Subjects from the Bible began to supplant the themes of aggression. Two Gethsemane scenes (Schw. 213, 214) date from 1915; in 1916 Corinth made the three prints of The Carrying of the Cross (Schw. L245, L246, 263; see Fig. 135), a Crucifixion (Schw. L285), and a set of six lithographs il-

Figure 150

Lovis Corinth, Beneath the Shield of Arms ,

1915. Oil and tempera on canvas, 200 × 120 cm,

B.-C. 656. Ostpreussisches Landesmuseum

Lüneburg.

lustrating episodes from the Apocalypse (Schw. L296). Here parallels can again be drawn between Corinth and the Expressionists. In 1916 Barlach transformed the idealized avenger of Holy War into a grotesque killer in a drawing and subsequent lithograph entitled Episode from a Modern Dance of Death . Rohlfs, Hofer, and Lehmbruck evoked the collective misery of the war in numerous paradigmatic portrayals of anguish, while with more than a touch of self-identification both Beckmann and Kokoschka turned repeatedly during these years to the iconography of Christ's Passion.

Figure 151

Lovis Corinth, Old Man in Armor , 1915. Oil on canvas,

125 × 91 cm, B. C. 654. Bezirksmuseum Cottbus; on loan

to Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, National-Galerie (DDR).

Themes of war are less frequent in Corinth's paintings. In 1914 he painted a knight in armor attacking a naked woman (B.-C. 619), and in 1915 he responded to the news that German troops had once again freed East Prussia from Russian occupation by painting a knight as a woman's stalwart protector (Fig. 150), inscribing the canvas "In Memory of the Assault on Memel."[39] Two other works from 1915 commemorate German heroes—Death Mask of Frederick the Great (B.-C. 653) and Martin Luther (B.-C. 655)—and a third depicts an old man in armor (Fig. 151); the model's feeble posture and dim gaze contrast

Figure 152

Lovis Corinth, Cain , 1917. Oil on canvas, 140 × 115 cm,

B.-C. 708. Kunstmuseum Düsseldorf (M 1986-4).

Photo: Landesverband Rheinland/Landesbildstelle

Rheinland.

sharply with the rigid strength of the weapons, testimony to a brave spirit seeking to defy the infirmities of old age. Borussia (B.-C. 705), the picture of an Athena-like Mother Prussia protecting a group of children around her; Cain (Fig. 152), a horrid rendering of the archetypal theme of fratricide; and a painting of yet another aged warrior, the historical figure Götz von Berlichingen (Fig. 153), all date from 1917. The knight, though fully armed for battle, is engaged not in martial pursuits but in committing his memoirs to paper. He writes with his left hand while his iron right hand, fashioned after his real hand was shot away during a siege, weighs heavily on the table. This work and the painting of the old man in armor from 1915 were preceded by etchings (Schw. 163B, 288), and it is difficult not to interpret both as surrogate self-portraits acknowledging that Corinth, too, experienced the war only from a distance. In the painting of Götz von Berlichingen, as in the earlier Samson Blinded (see Plate 22), the setting is a modern interior. Indeed, the framed

Figure 153

Lovis Corinth, Götz von Berlichingen , 1917. Oil on canvas, 85 × 100 cm, B.-C. 725.

Museum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte der Stadt Dortmund (C 4790).

Figure 154

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait in a White Smock , 1918. Oil on canvas,

105 × 80 cm, B.-C. 734. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne.

Photo: Rheinisches Bildarchiv.

works of art in the background evoke the ambience of Corinth's own studio, where he often sat during these years engaged, like Götz, in writing his autobiography.

The theme of aggression is embodied once again in Rape (B.-C. 726), a painting from 1918, while Young David (B.-C. 731) from the same year conjures up the hope for victory and deliverance. Corinth's inability to sustain this hope, however, is evident from his diary. "It is horrible and terribly sad," the entry for October 17, 1918, concludes, that "after the war there will be peace, but it will arrive like the peace of the grave."[40] On November 3, the day of the armistice, he wrote: "The world of Bismarck and the Hohenzollerns has ceased to be. . . . A world of enemies has finally conquered us."[41] Two days later he wrote a single line in his diary, Hector's prophecy of the fall of Troy: "The day will come when sacred Ilion will fall, Priam too, and the people of the brave king."[42] In Corinth's final war painting his armor lies discarded, like a useless prop, on the floor of his studio (B.-C. 727).

Germany's defeat in the war was a harsh blow for Corinth, the more so since as a native East Prussian he identified personally with the Prussian state. As late as November 1, 1918, he still expressed the hope that the kaiser, no matter what his shortcomings and blunders, would not be forced to abdicate, that he would be supported, if need be, by the military.[43] Even after the out-break of the revolution Corinth declared proudly: "I consider myself a Prussian and a German of the Empire."[44]

Despite Corinth's trials during these years, his reputation continued to grow. The year 1917 in particular brought him much professional satisfaction. Major exhibitions of his works were held at the Kunsthalle in Mannheim and at the Kestner-Museum in Hannover; the Delphin Verlag published Herbert Eulenberg's biographical essay; and Fritz Gurlitt brought out Karl Schwarz's catalogue of Corinth's graphics. To cap it all, the Prussian Ministry of Culture bestowed on Corinth the title Professor, and the city magistrates of Tapiau made him an honorary citizen. The second edition of Corinth's autobiographical account Legenden aus dem Künstlerleben was published in 1918; in early March of that year the Berlin Secession opened a large retrospective in celebration of his sixtieth birthday.

Corinth himself marked the occasion with a self-portrait (Fig. 154). The colorism of this painting is unusually subdued: tones of white and gray predominate, enlivened sparsely with touches of green, yellow, and rose. The pictorial structure, as in Poussin's famous self-portrait in the Louvre, is determined by the framed canvases in the background. The bold brushstrokes,

Figure 155

Lovis Corinth, Self-Portrait at the Easel , 1918. Etching, 25 × 18 cm,

Schw. 337. Staatliche Museen Preussischer Kulturbesitz,

Kupferstichkabinett, Berlin (West) (192-1931).

Photo: Jörg P. Anders.

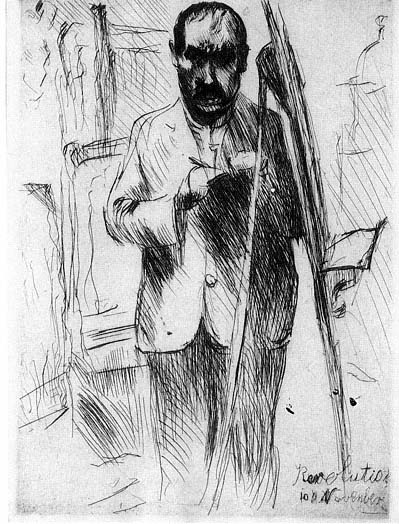

however, defy the strict logic of the composition, as does the painter's expressive gaze. Once again Corinth depicted himself in the act of painting. Prominently inscribed with roman numerals designating his age, the picture testifies to his undiminished commitment to his work. Several years later, reminiscing about the events of 1918, he did indeed write in his diary: "I had hoped to contribute to the recovery of Germany by creating works as good as I could possibly make them."[45] That his studio had become a place of refuge in a chaotic world is also suggested by the self-portrait etching inscribed "Revolution/10. November 1918" (Fig. 155). Whereas images of death had set an apprehensive tone for the two self-portrait etchings from 1916, here Corinth, surrounded by the implements of his profession, records his likeness with quiet resolution, a pillar of calm in a world gone berserk.

The real celebration of Corinth's sixtieth birthday, on July 21, took place in the secluded hamlet of Urfeld, at the shores of the Walchensee, in Upper Bavaria, where the painter and his family had taken lodgings at the Hotel Fischer am See. Although he was deeply moved by the beauty of the Walchensee, Germany's largest and deepest Alpine lake, he did not yet realize that this encounter with Urfeld and its environs would open a whole new chapter in his life.