2

War on the Enemy Mind

Mobilization for War

Well before the attack on Pearl Harbor, psychological experts began mobilizing to assist the war effort.[1] Their preparations, from the start, illustrated an awareness that offering patriotic assistance, earning professional advancement, and bringing psychological enlightenment to the business of government proceeded happily in unison. This link had been forged for psychologists during their first experience of world war, when they learned that war could accomplish what brilliant academic research and dedicated teaching failed to do. World War I "put the applications of psychology on the map and on the front page," fondly recalled James McKeen Cattell, a founding figure in professional psychology.[2]

Few such reminders were required. Psychology's historical debt to war was made abundantly clear by pivotal figures in World War I psychology who were still alive and professionally active in 1940.[3] Robert Yerkes, for example, had directed the military's mental testing program during World War I and became well known in the interwar period for his pioneering work in comparative psychology and primatology at Yale.[4] In preparation for World War II, he worked as a key member of the Emergency Committee in Psychology, launched in fall 1939 "to prepare the profession for a great national crisis."[5] The Emergency Committee, reorganized one year later under the auspices of the Division of Anthropology and Psychology of the National Research Council

(NRC), served as a central vehicle for mobilizing psychological experts for war work, reorganizing the profession, and planning for the postwar future. As psychology's "war cabinet," it served as the official link between many psychological professionals and the federal government.[6]

Psychological experts were early stirred to patriotic action, and they were optimistic from the outset that the war would do great things for their professions. According to Yerkes, effective mobilization would demonstrate "a large uncultivated professional area which should speedily be occupied by the psychotechnologies and related aspects of human engineering."[7] There was a gaping hole, which it was psychology's wartime mission to fill, in expert services related to "the facilitation and intelligent direction of the development and current behavior-experience of the normal person."[8] Everything from advice about childrearing and marriage to occupational counseling and education for personal happiness and adjustment would be needed. "I am looking beyond the present world conflagration," Yerkes boldly predicted in April 1941, "to a period of reconstruction during which innovations are likely to be the unescapable order of the day and the fashioning of a new civilization a necessity."[9]

Many of Yerkes's colleagues heeded this spirited call to public service and professional opportunity, confident that few experts were better suited than they for the task of designing a new social order. Before the United States had been in the war for a year, a full 25 percent of all Americans holding graduate degrees in psychology were at work on various aspects of the military crisis, most employed full-time by the federal government.[10] "This is no time for feelings of inferiority or for statistical scrupulosity," wrote prominent personality and social psychologist Gordon Allport in an effort to inspire "a bit of boldness" and calm the nerves of colleagues reluctant "to advocate policies not based upon 100 per cent scientific certainty."[11] "If the psychologist is tempted to say that he knows too little about the subject he may gain confidence by watching the inept way in which politicians, journalists, and men in public life fence with the problems of propaganda, public opinion, and morale."[12]

There were reasons to guard against overconfidence, however. In early 1941 Allport warned his colleagues: "Don't confuse lobbying for psychology with national service: —Working for the introduction of psychologists into national and local services may be helpful to the profession, but it is not necessarily beneficial to the nation."[13] The evolving relationship between psychologists and government could, Allport

thought, also pose problems. "Apparently the closer one comes to the Government," he noted, "the more complications and resistance one encounters. But after all, don't we all tend to reify 'the Government' and expect 'it' to help materialize our ideas? My experience, too, suggests that decentralized efforts are better. It is 'we, the people' who must invent and execute projects, so far as we can, by ourselves without leaning too much on Uncle Sam."[14]

By 1945 Allport and others were astounded when they compared their initial assessments of what psychology could contribute to the war effort to what had actually happened. The war ended amid a loud chorus of self-congratulations such as the following: "The application of psychology in selecting and training men, and in guiding the design of weapons so they would fit men, did more to help win this war than any other single intellectual activity."[15] Psychology's record had been impressive indeed, and as if to prove it, there were not nearly enough trained experts around to meet the rapidly increasing demand for psychological services in both the public and private sectors. The reputation of psychological experts had risen from one of lowly technicians to one of wise consultants and managers whose wartime accomplishments, especially in the military, deserved a generous payoff in public appreciation and government funds. In retrospect, it seemed clear that the war had given psychology its biggest boost ever, prodding the APA "to grow up to its responsibilities in this new world."[16]

Many psychiatrists were similarly motivated to build on the blueprint offered by their predecessors during World War I, vindicate their techniques of diagnosis and prediction, and recapture any ground that might have been lost due to psychological disarmament during the isolationist interwar period. At the outset of World War II, psychiatrists relied (just as psychologists did) on their World War I track record in testing and screening military recruits for potential emotional liabilities. Psychiatrists, however, had even older prototypes of service to the state to inspire their World War II effort, including the pioneering work of the Public Health Service's (PHS) psychiatric team, stationed on Ellis Island in 1905, for the purpose of keeping insane, and therefore undesirable, immigrants from slipping into the country.[17] The PHS psychiatric team was among the very first examples of psychological expertise being deployed by the federal government in an important area of public policy—immigration—distant from psychiatry's traditional spheres of authority: insanity and asylums.

One tremendous advantage the experts had in 1940 was that there

were so many of them, at least in comparison to their numbers in 1917. Among psychiatrists, nearly 3,000 eventually participated in the World War II screening program, compared to a mere 700 in World War I. In both world wars, however, psychiatrists involved in wartime screening programs represented the vast majority of all U.S. psychiatrists: less than 1,000 at the time of World War I and more than 2,500 in 1941, when the United States entered World War II.[18] Between 1920 and 1946, membership in the American Psychiatric Association had increased more than fourfold, from 937 to 4,010, with a surge of new recruits added to the professional ranks as a result of their war experiences.[19] American Psychological Association membership had grown more than elevenfold during these same years, from 393 to 4,427.[20] At the close of World War II, around 1,700 psychologists worked directly for the World War II military, and many others had been involved in research for and consultation to war-related government agencies. A significant number—especially women—made war-related contributions in civilian areas ranging from organizing community forums for women newly employed in the war industries on how best to feed their babies to the general dispensation of "Psychological First Aid."[21] By 1945 the total numbers of psychologists and psychiatrists were running about even. Both professions would experience a historically unprecedented postwar growth curve, far outstripping general population growth or even the spectacular growth of the health-related professions.[22]

What They Did and What They Learned

The wartime psychological work detailed in this chapter and the next is nonclinical. Many practitioners who worked in areas such as "human management" and enemy morale were social psychologists or other social scientists deeply influenced by psychological theory. Social interests notwithstanding, they considered themselves as firmly committed to rigorous scientific practices as colleagues located at the more physiological end of the professional spectrum. For the most part, experimentalists who were interested in such problems as sensation and perception were involved in "man-machine" engineering problems during the war. A visible example was the Harvard Sound Control Project, which significantly improved earplug technology with a huge staff of psychologists and a $2 million government contract. Psychological

scientists also conducted laboratory and field experiments designed to produce more user-friendly gunsights, improve night vision, and increase the efficiency of cargo handling, among other things. The young B. F. Skinner even spent the war years trying to prove the military value of behaviorist principles by demonstrating that living organisms—pigeons, to be precise—could be as dependable as machines when it came to guiding missiles to their targets.[23]

Clinically oriented professionals, whose activities are discussed in chapter 8, became the best known of all the wartime psychological experts for their efforts to identify and counter an epidemic of mental disturbance and incompetence. Although they entered the war years with far less professional clout than their experimentalist colleagues, the tables would turn dramatically in the postwar era, when clinical work soared to unprecedented heights of visibility, authority, and political importance.

Although the absolute numbers of experts involved in the areas of work described below were smaller than the numbers of clinicians who maintained the military's mental balance by screening recruits and administering classification tests, their work indicated more directly how psychological knowledge could be made useful to problems defined in explicitly political and military terms. How could enemy soldiers be most effectively reached with demoralizing messages? How could relocation centers for Japanese-Americans be run smoothly? How could U.S. public opinion be oriented toward supporting particular war aims and away from the powder keg of racial conflict? How could U.S. soldiers be convinced that harsh military policies were actually justified, fair, and deserving of compliance?

To these and other questions some psychological experts devoted the war years. If they felt they were advancing the causes of scientific knowledge and professional achievement (and most of them did), they also knew that their jobs existed not for these purposes, but to provide policy-makers with practical, timely, and applicable analysis and information. For each optimistic assessment that social scientists were "gradually creeping up the administrative ladder," and "see[ing] to it that many of our ideas get 'stolen' by government," there were others who glumly reported that "none of our memos were worth anything and they were the joke of Washington."[24] Dedicated throughout the war to enlarging their own sphere of influence, experts nonetheless quickly grasped that furthering a psychological science of social relations or theory of society was not the point. Winning the war was.

Although human relations advisors, specialists in psychological war-

fare (sometimes called "sykewarriors"), morale specialists, and opinion pollsters spent their time occupied with pressing policy matters, they drew on much the same body of psychological theory and behavioral experimentation available to clinicians. The primary wartime commitment of policy-oriented experts was to making psychology useful, but they also considered the military to be the best environment for large-scale research they had ever encountered. Figures including Eli Ginzberg, Daniel Lerner, Alexander Leighton, and Samuel Stouffer referred to the military as a "laboratory" and observed that war presented unmatched opportunities for scientific experimentation into the mysteries of human motivation, attitudes, and behavior.[25] They were usually careful, however, to keep such language to themselves, understandably nervous that their "subjects" would resist being cast as rats and guinea pigs .[26]

The work of policy-oriented experts grew out of the same intellectual roots as that of their clinical counterparts, a fact that would have profound importance to the political course and public consequences of psychological expertise in the postwar decades. Their professional training led them to adapt concepts developed initially to shed light on how individuals coped with unhealthy situations, or responded to psychopathology—frustration and aggression, for example—to analyzing social issues and designing public policy. One important result would be to blur the line between the individual and the collective, the personal and the social, and to create the potential for camouflaging clear political purposes as neutral methods of scientific discovery or therapeutic treatment. (The career of psychology during the Cold War, and its role in postwar race relations—the subjects of chapters 4 to 7—offer fascinating evidence of exactly how far this process could, and did, go.)

Psychological experts who aided in wartime administration, for example, drew on the language of health, illness, and therapeutic treatment that was the legacy of psychiatry's historic basis in medicine. Psychiatrist Alexander H. Leighton, head of the research team at the Poston Relocation Center for Japanese-Americans and later head of the Foreign Morale Analysis Division (FMAD) of the Office of War Information (OWI), encouraged those with whom he worked to adopt a "psychiatric approach in problems of community management."[27] Psychologists also tended to draw their inspiration from the biological and physical sciences. Samuel A. Stouffer, a psychologically oriented sociologist who directed the army's most ambitious in-house effort in attitude assessment, reflected constantly on the methods of scientific practice—especially controlled experimentation—that had unlocked the

wonders of biology and chemistry and that he hoped would do the same for behavioral scientists, finally allowing them "to take some hypotheses of a general character, express them in precise operational terms, and devise means for crucial tests.... so that inferences and applications can be made from them to broad classes of concrete behavior situations."[28]

The example of World War I loomed large for these nonclinical experts. Propaganda efforts and shocking evidence of mental deficiency in the military during the Great War had done much to expose the ugly truth of public gullibility, mass emotionalism, and widespread distortions in the popular perception of important public issues. The experience turned even such democratic idealists as Walter Lippmann toward a despairing, and sometimes cynical, belief that only rational experts were in a position to understand "the world outside" and should therefore have the power to engineer public opinion, or what he called "the pictures in our heads."[29] World War I taught that representative democracy was far too emotionally unstable to safely determine the future course of U.S. society and that only those whose educations shielded them from ordinary irrationality should wield the power to make and shape public policy. Thus did science and liberal democracy diverge.[30]

No science poked more holes in democratic ideals than psychology. Many psychological experts were converted by World War I to the principles of crowd psychology, a theoretical tradition first articulated in the late nineteenth century by the aristocratic and antidemocratic French sociologist Gustave Le Bon.[31] Le Bon pointed to the unreason and intolerance of collective behavior and mass attitudes as the hallmark of contemporary society and as alarming threats to civilization. He called upon rulers to exert strict social controls over the emotionally explosive masses, protect the eroding powers of intellectual and governing elites, and champion the noble but rapidly evaporating ideal of the individual. During the Progressive Era, pioneers in social psychology like William McDougall (whose career had begun in Britain) and Everett Dean Martin popularized Le Bon's theories.[32] The tradition of crowd psychology also reached U.S. audiences through Freudian social theory and concepts like that of the primal horde.[33] While the elitist attacks of European intellectuals on liberal democracy were often dulled or deleted in U.S. social psychology, the analysis of crowd behavior was destined to remain a centerpiece of U.S. political criticism for a long time to come. The usefulness of crowd psychology derived from its quality of translating contentious questions of political ideology into objective axioms of social science.[34]

By the end of World War I, politicians too had embraced psychopolitical perspectives from the Le Bon lexicon. Herbert Hoover, for example, who had provided heroic relief to the hungry masses in German-occupied Belgium before going on to manage the wartime production and marketing of food at home, spoke up for the precious American individualism he believed to be under attack by the psychology of the mob. "Acts and ideas that lead to progress are born out of the womb of the individual mind," he commented, "not out of the mind of the crowd. The crowd only feels: it has no mind of its own which can plan. The crowd is credulous, it destroys, it consumes, it hates, and it dreams—but it never builds.... Popular desires are no criteria to the real need; they can be determined only by deliberative consideration, by education, by constructive leadership."[35]

Political scientist Harold Lasswell, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on the subject of World War I propaganda, also helped to disseminate crowd psychology. During the interwar period, Lasswell was instrumental in promoting the application of psychological theories and methods—especially psychoanalysis—to political problems from his post at the University of Chicago.[36] His theoretical and practical work on the margins between psychology and politics helped to cement a notion that would become an unquestionable axiom for the World War II generation: that widespread social conflicts like war and revolution were simply examples, on a large scale to be sure, of the problems that plagued individual personalities and inharmonious interpersonal relationships. Since society was nothing more than an agglomeration of many individuals, the quest for systematic laws of social and political misbehavior should be directed toward the very issues—unconscious motivation and irrational behavior—that the psychopathological approach had uncovered in mentally disturbed individuals. The many disasters of World War I, according to Lasswell, had "led the political scientist to the door of the psychiatrist."[37]

World War II, he hoped, would lead policy-makers to the same place in time to pioneer a new "politics of prevention" before too many mistakes occurred. Lasswell's advocacy of "prevention" came earlier than most, but before the end of World War II this code word reflected both widespread agreement and extreme optimism among psychological experts about therapeutic outcomes as well as policy-oriented work. Prevention was a useful vehicle for the professions' ambitions because it allowed their authority to expand in new directions, offering an open invitation to psychologists, psychiatrists, and allied professionals to in-

volve themselves in areas as distant from their traditional turf as unemployment, housing shortages, occupational health and safety, political corruption, and international relations.[38]

The mantra of prevention was, in a sense, a continuation of experts' Progressive Era love affair with efficiency and reform and it followed closely on the heels of the twin campaigns for scientific management and mental hygiene early in the century.[39] But prevention had also absorbed new justifications. No longer was it animated mainly by visions of uplift in a society coming to grips with urban culture, mass institutions, and, at least for native-born whites, an unsettling new ethnic diversity. Before the end of World War II, experts would champion prevention not primarily because it made expert talents indispensable to reform activities, but rather because conventional distinctions between positive mental health and social welfare, or proper adjustment and wise public policy, had almost entirely collapsed.

Lasswell was in the vanguard of this new, integrated understanding of psychology and politics. For him, "prevention" meant treating the issue of power as an issue of psychological management on a social level—releasing uncomfortable tensions here, adjusting sources of strain there—and transforming the exercise of power into something resembling enlightened psychiatric treatment. Straightforward conflicts of interest, consequently, need never disturb the collective peace of mind. "The politics of prevention does not depend upon a series of changes in the organization of government," he argued. "It depends upon a reorientation in the minds of those who think about society around the central problems: What are the principal factors which modify the tension level of the community? What is the specific relevance of a proposed line of action to the temporary and permanent modification of the tension level?"[40]

Human Management

Among the most straightforward examples of psychological expertise used for political purposes during World War II were researchers and analysts who used the tools of their trade to assist public administrators. They did not have to be told to subordinate the goal of knowledge production to that of human management. It was simply understood that war "forces all scientific efforts to short cuts" and that

their job description involved producing tips on how to control people effectively rather than theories that might explain previously obscure aspects of social life.[41]

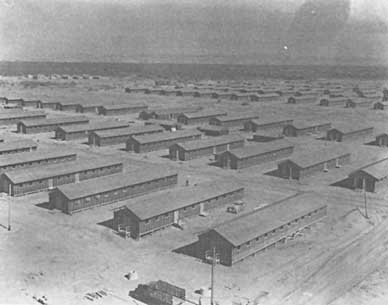

The Sociological Research Project, located in the Poston Relocation Center for Japanese-Americans in the Colorado River Valley, was a clear example of psychology's usefulness in this area (fig. 1).[42] Brought into existence through the forceful advocacy of War Relocation Authority (WRA) consultant Robert Redfield (dean of the Division of Social Sciences at the University of Chicago) and other believers in the administrative value of applied social analysis, the project was directed by Alexander H. Leighton, a navy psychiatrist with some previous field experience in Navajo and Eskimo communities. This innovative research effort was initiated in March 1942, shortly after the decision had been made to intern the 112,000 Japanese-Americans living on the Pacific Coast. The express intention was to experiment with techniques of human management that would prove useful to internment managers and, at the same time, prepare field workers of Japanese ancestry to help with the military occupation that was being planned for various areas of the Pacific.[43] Constructed on the model offered by the Office of Indian Affairs, which had used social scientists as administrative aides in the past, Leighton's research team brought the tools of psychological theory, psychiatric treatment, and cross-cultural research to bear on the management problems at hand. He consciously organized the effort by professional and amateur social scientists (trained in cultural anthropology, sociology, and psychiatry) along clinical lines, "but with the community rather than patients being the subject of study."[44]

Leighton's team members included anthropologists Edward H. Spicer and Elizabeth Colson as well as typists, artists, and translators drawn from among the camp's better-educated population.[45] They specifically disregarded the question of whether the evacuation itself was justified, noting only that "these questions involve matters concerning which data for forming an opinion are not available at present."[46] . They did, however, dutifully apply themselves to helping administrators run the Poston Center and maintained a firm belief that their work would help to uncover the invisible laws of individual and social behavior, thereby strengthening the partnership between science and government.

The greatest promise [of the project] for men and their government, in stress and out of it, is in a fusion of administration and science to form a common body of thought and action which is not only realistic in the immediate sense

Figure 1. Aerial view of Poston Relocation Center for Japanese-Americans,

where World War II experts aided administrators by applying "the psychiatric

approach in problems of community management." Photo: National Archives.

of dealing with everyday needs, but also in the ultimate sense of moving forward in discovery and improved practice. This requires more than hiring social scientists to make reports. It requires an administration with a scientific philosophy which employs as its frame of reference our culture's accumulated knowledge regarding the nature of man and his society.[47]

To this end, the researchers began with a "fundamental postulate" about basic human nature: the psychological self was a universal entity in which many cultural variations appeared. Their assumptions about the psychological status of center residents all followed from their understanding of basic human nature and of fundamental parallels between mass and individual psychology. These assumptions can be summarized as follows: behavior was largely irrational, motivated by emotion and past experience (especially childhood); residents' perceptions of their internment (their subjective "belief systems") were more important than what had actually happened to them (the "objective facts") and whether or not internment was morally justified; dangers

lurked in groups because individual fears and resentments could be kin-died into hysterical and difficult-to-control crowd behavior.

Day to day, the research team conducted intensive interviewing and personality analysis and gathered general sociological data by compiling employment and education records. Staff members prepared oral and written reports that predicted reactions to an array of possible administrative moves and tried to guide management in the directions suggested by their working assumptions. "The administrator who approaches turbulent people with reason is likely to get about as much result as if he were addressing a jungle," was a typical example.[48] While team members could find themselves coping with such humdrum annoyances as unruly teenagers, they tried to concentrate on analyzing and reducing resistance to the overall relocation program as well as to particularly controversial policy suggestions, like registering each camp member for the purposes of a loyalty interrogation. In the latter case, the psychological experts' recommendations were considered important enough to be classified as confidential and circulated at very high policy-making levels.

The picture of the center that emerged from their work was of a community in psychological turmoil, cut off from previous sources of stability, anxious about what other citizens thought of Japanese-Americans, and internally divided along generational, Issei-Nisei lines. Most of all, residents needed a sense of security. Hence, providing it was the surest route to effective administration of the center. When the arrest and detention of two camp residents in a beating incident provoked a general strike at the center, the research team's recommendations helped to defuse mounting tensions quickly and peaceably. Leighton's group pointed out that some administrators' impulse to respond with force rested on a foundation of irrational, racist stereotyping and suggested instead that camp residents be granted more responsibility for maintaining order themselves. The team's recommendations for instilling security through self-government (compiled in a memo written by Conrad M. Arensberg, associate professor of sociology and anthropology at Brooklyn College) won acclaim among high-level policy-makers in the Washington office of the WRA, and resulted in the addition of a community analyst to the staff of every WRA camp in January 1943.

The general conclusions of the Poston team, summarized by Leighton in The Governing of Men: General Principles and Recommendations Based on Experience at a Japanese Relocation Camp (1945), were that human management techniques had to be as psychologically and emo-

tionally oriented as their object. According to Leighton, "Societies move on the feelings of the individuals who compose them, and so do countries and nations. Very few internal policies and almost no international policies are predominantly the product of reason.... To blame people for being moved more by feeling than by thought is like blaming land for being covered by the sea or rivers for running down hill."[49] . The best measures of social control necessarily embodied a sophisticated psychology, since managing people effectively entailed managing their feelings and attitudes, far more a question of engineering self-controls than imposing external punishments.

Enemy Morale: Warfare Waged Psychologically

Work in the fields of psychological warfare, propaganda, and intelligence fell into the sweeping, but undifferentiated category of "morale." The concern with morale that pervaded the war years represented the recognition by government officials that the human personality and its diverse and unpredictable mental states were of utmost importance in prosecuting the war. Moods, attitudes, and feelings were not simply appropriate objects of military policy; they were the most appropriate, and objective facts receded into the background. The naive idea that wars could be won simply by perfecting weapons technology to kill one's opponents, it was noted frequently, was incorrect. By far the most effective road to victory was to destroy enemy morale while bolstering one's own.[50] There could be no higher military priority than the control of human subjectivity.

Applied to Americans or the Allies, "morale" was used loosely to describe desirable qualities ranging from personal bravery to group spirit. It also functioned as shorthand for determination, sense of purpose, superb leadership, and occupational competence in military and civilian populations. Positive "morale" was essentially the equivalent of positive motivation, a conspicuous component of "mental hygiene" (the most common term before World War II) or "mental health," as it was increasingly called. Because it could prevent neurotic breakdown and loss of cohesion, fortifying Allied morale became a central war aim. Destroying it in the enemy was, of course, equally vital.

Early on in the war, Army Intelligence asked the NRC Division of

Anthropology and Psychology for urgent help in the area of morale since no psychological warfare program existed at the outset of the conflict.[51] As programs were constructed, "morale" came to designate activities as seemingly different as analyzing enemy communications, monitoring U.S. public opinion, gathering data on what made German and Japanese civilians tick, and keeping the spirits of U.S. GIs as high as possible.

The elasticity of morale's definition elevated the public worth of psychological experts, since if psychological experts had nothing else in common, they were at least supposed to be united in their obsession with "the mind." ("Mental processes" was much preferred by those experimentalists who resisted the metaphysical etymology of this term.) Significantly, morale also stretched the definition of war to encompass aspects of civilian social life previously considered off-limits to military policy-makers, such as influencing levels of community cohesion and confidence in political leadership. The wartime recognition that battles over hearts and minds did not stop respectfully at the edges of military institutions, that civilian minds (ours and theirs) were coequal targets, would have momentous implications for the future.

Work having anything to do with the mental state of the enemy was generally labeled "psychological warfare," and the frequency of this term's use during World War II indicated how many more elements of warfare were being considered as components of a psychological conflict. This new designation tended to replace "propaganda," the term most used during World War I. At that time, "propaganda," had denoted only that portion of psychological warfare having to do with mass communications aimed at enemy audiences. Psychological warfare, on the other hand, was much broader in meaning. The terminological shift corresponded to a shift in the concept of war itself: from a tangible battle to conquer hostile geography to an intangible battle to persuade hostile minds.

Not surprisingly, this shift sharply underlined the importance of psychological experts in determining the outcome of military conflicts. Harold Lasswell, in fact, noted that the high profile of psychological warfare in World War II came about because "the psychologists wanted 'a place in the sun'; that is, they were eager to demonstrate that their skills could be used for the national defense in time of war."[52] At the same time, the new emphasis on nonmaterial determinants of military outcomes blurred the distinction between war and peace, a confusing state of affairs that would come to feel entirely normal during the Cold War. If aspects of warfare that were not military in the conventional

sense of armed conflict could make the difference between a short and relatively bloodless war and one that was long and deadly, why not consider any method of resolving conflict without resort to troops and guns a component of warfare? Effective diplomacy, Lasswell pointed out, could keep potential enemies neutral or utilize secret channels to bring war to an end, and strategically applied economic muscle could prevent enemies from gaining access to key, war-making materials.[53]

Unlike the arsenal of persuasion trained on enemy and occupied territory, work on the mental state of Americans or Allied populations (civilian and military) was never called psychological warfare, even though it did fall under the "morale" umbrella. There were, however, no important differences in the methods used to assess or persuade the two very different audiences; shared techniques included public opinion polls, attitude surveys, in-depth interviews, and personality analysis. Nor were there any differences in the professional training of those who spent the war years taking the pulse of U.S. morale rather than studying enemy minds. Not infrequently, the same people did both. And not infrequently, the policy-makers interested in enemy morale took an equal interest in its home front counterpart.[54]

The perspective that psychological experts brought to their work on enemy morale was, like that of the relocation management assistance team described above, based on a conviction that emotional appeals worked more effectively than rational ones and that chaotic irrationality infected human motivation to a much greater extent than orderly and thoughtful ideals. Similarly, those working on enemy morale did so out of a fierce conviction that behavioral insights could be powerful enough, if taken seriously, to tip the balance in the war, not to mention improve immeasurably the efficiency of military policy-making and war management. Individuals identified with this work included psychologists Leonard Doob and Edwin Guthrie and psychiatrist Alexander Leighton, among others. They worked in a range of agencies charged with understanding and influencing enemy morale, including the Office of Facts and Figures (OFF), the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the Office of War Information (OWI), and the Psychological Warfare Division (PWD) of Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF).

Others worked outside of government, in academic institutions and community agencies, but in capacities that contributed directly to the psychological warfare effort. Typically, they coordinated their projects closely with government agencies and officials. Work in this field sometimes moved back and forth between public and private status. The

Ethnographic Board, set up by the Smithsonian Institution, the NRC, the Social Science Research Council, and the American Council of Learned Societies, compiled a central register of all U.S. social and behavioral scientists who had done foreign area research, complete with bibliographies and reports on obscure corners of the world. Harold Lasswell, whose content analysis technique inspired a tidal wave of "propanal" (short for propaganda analysis), worked initially on the Wartime Communications Research Project and then the Experimental Division for the Study of Wartime Communications. Both located in the Library of Congress, the first project was set up to afford Lasswell access to documents he could not have obtained without a governmental connection, and the second became a training ground for propaganda analysts.[55] Lasswell then moved over to the New School for Social Research, where he jointed Ernst Kris and Hans Speier in the Research Project on Totalitarian Communications.

Many psychological experts interested in systematically investigating mass communications and propaganda were brought together in the Communications Group of the Rockefeller Foundation, part of that organization's contribution to mobilizing U.S. intellectual resources for war, openly and in secret.[56] Among the many projects it supported were two at Princeton. The Princeton Listening Center, relocated in Washington in 1941, was incorporated into the Federal Communications Commission as the Foreign Broadcast Monitoring (later Intelligence) Service, where it was directed by Goodwin Watson, a social psychologist (fig. 2). The Princeton Office of Public Opinion Research was established in 1940 to analyze European radio broadcasts and diagnose Nazi psychology. Psychologist Hadley Cantril, a key figure in work on both enemy and home front morale, was its founder. In his opinion, many advantages existed in working outside of official circles, because doing so made it "possible for me to get confidential information for President Roosevelt and various other people in Washington without having to tie myself down to any government department or agency."[57]

National Character: Personality Diagnosis and Treatment on an International Scale

World War II underscored the real difficulties involved in distinguishing between friends and enemies. Because the war's ideological clashes made it impossible to trust such tangible indicators of loy-

Figure 2. Princeton Listening Center.

Photo: Courtesy of the Rockefeller Archive Center.

alty as what people said and how people behaved, understanding the deep mental state of German and Japanese populations became a prerequisite to good military strategy. To this challenge, psychological experts brought the innovative concept of national character.[58] Nurtured by the neo-Freudian movement to revise psychoanalytic orthodoxies considered insufficiently attentive to the impact of social context on psychological development, writings by Franz Alexander, Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, and Harry Stack Sullivan had already attracted a lot of attention by the early 1940s.[59] So had similar theoretical work by cultural anthropologists (many of them students of Franz Boas) such as Gregory Bateson, Ruth Benedict, Geoffrey Gorer, Margaret Mead, and Edward Sapir.

Their collective efforts to "study culture at a distance" were sometimes designated as the "cultural interpersonal school" or simply as studies in "culture and personality."[60] A blend of psychological, sociological, and anthropological analysis was typical of this work, and at its heart lay the conviction that microscopic questions about individual personality and behavior and macroscopic questions about societal patterns and problems were nothing but two sides of the same coin.

"Problems of social science differ from problems of individual behavior in degree of specificity, not in kind," wrote Edward Sapir, the author of an influential series of essays explaining why cultural anthropology needed an infusion of psychological ideas.[61] Wartime research on the culture and personality model anticipated some of the most characteristic features of postwar social science: the powerful appeal of psychological insights and techniques, an adamantly interdisciplinary style, and the conviction that a unified social expertise was possible and absolutely necessary to a modern democracy.

By suggesting that psychological development and national patterns created each other, that individuals embodied their culture and cultures embodied the collective personality of their people, national character offered a way of turning psychological insight into policy directives. National groups, for example, would be classified according to the "bipolar adjectives" most familiar for their power to describe individual personality: dominance and submission, exhibitionism and spectatorship, independence and dependence, and so on.[62] Institutional vehicles of socialization, from childrearing to teacher training, could then be scrutinized for tendencies in one direction or another, and after tallying enough of these national indicators, one could hope to achieve an accurate portrait of a given country's collective personality structure.

Exploring the concept in detail and in a hurry was a military imperative, as well as an intriguing theoretical exercise, as Geoffrey Gorer, a major proponent of national character, pointed out.

The conduct of the war raised in an urgent fashion problems of exactly the nature I have been outlining—problems of national character, of understanding why certain nations were acting in the way they did, so as to understand and forestall them. Germany, and even more Japan, were acting irrationally and incomprehensibly by our standards; understanding them became an urgent military necessity, not only for psychological warfare—though that was important—but also for strategic and tactical reasons, to find out how to induce them to surrender, and having surrendered to give information; or, in the case of occupied countries, how to induce them to create and maintain a resistance movement, and so on. In an endeavour to further the war effort, a small number of anthropologists and psychiatrists were willing to risk their scientific reputations in an attempt to give an objective description of the characters of our enemies.[63]

In one neat package, the notion of national character oriented psychology toward understanding and affecting important public issues, without sacrificing the traditional language of sickness, health, and di-

agnosis. But it was the war that changed national character from a concept for which a daring few would "risk their scientific reputations" into a working assumption of military policy.

In a pivotal 1936 article, Lawrence K. Frank, an advocate of clinical approaches whose influential foundation posts had included the Rockefeller Foundation and the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, pointed out that if nations had characters, then it made sense to think of "society as the patient": "There is a growing realization among thoughtful persons that our culture is sick, mentally disordered, and in need of treatment."[64] Frank believed this perspective would move behavioral experts from the limited turf of individual adjustment to the more expansive, and therefore hopeful, terrain of social problem management. This served the dual, and entirely compatible, purposes of expanding psychology's sphere of professional influence and treating problems that stubbornly resisted piecemeal amelioration. Finally, it was practical. Since the ideology of democratic individualism and personal responsibility was obviously outmoded in an era of wholesale cultural disintegration, bringing therapeutic methods to beacon society at large promised to simplify the complicated job of social analysis by demonstrating that social forces and social organization were just as disorderly and abnormal as people analyzed one at a time.

As the news from Europe got worse, more and more experts embraced the disease metaphor. In 1940 psychiatrist Edward A. Strecker wrote that wars were nothing but "mass homicidal reactions" and ominously concluded that "unquestionably the world is sick—mentally sick."[65] But if society were a sick patient, then it could recover, especially if the right healers were consulted. Psychiatrist Richard Brickner endorsed this view in his 1943 book, appropriately rifled Is Germany Incurable? After noting that "the national group we call Germany behaves and has long behaved startlingly like an individual involved in a dangerous mental trend," he confidently asserted that "anthropology, psychiatry and sociology are probably well enough advanced by now to make 'treatment' conceivable."[66] That treatment would involve a wholesale therapeutic strategy for postwar German society, in which citizens were inoculated against "paranoid contagion" via an artificially designed emotional atmosphere. Brickner compared this "treatment" to placing a premature newborn in an incubator.[67]

War work was a warmup for nothing less than "restructuring the culture of the world," agreed Margaret Mead.[68] The sense that responsibility was tied to power underlay all wartime work on morale. Not

only could psychological experts decipher the emotional patterns of enemy propaganda to help win the war; they could also hope to become social engineers at war's end, designing a blueprint for psychological reconstruction on a mass scale that would bring the national characters of Germany and Japan back into the normal range, away from perverse dependence and toward a healthy self-reliance.[69] For the experts involved in psychological warfare, the innovative concept of national character, however rudimentary, illustrated what colleagues were learning in fields far removed from wartime activity: military usefulness and scientific progress were entirely compatible, even destined for a glorious and coordinated march into the future.[70]

The effort to scientifically systematize the basic elements of psychoanalysis, in the form of a series of concrete behavioral principles that could be empirically or experimentally validated, was another important theoretical development within psychology during the World War II era. It had a major influence on the techniques experts used both to boost and to destroy morale. Located at the Yale Institute of Human Relations, the effort to generate a "science of human behavior" was related to but distinct from the "culture and personality" studies mentioned above. Psychologists affiliated with the effort at various points in the 1930s and 1940s included John Dollard, Leonard Doob, Erik Erikson, Ernest Hilgard, Clark Hull, Neal Miller, O. H. Mowrer, Robert Sears, and Robert Yerkes.[71]

One trademark Yale product, published on the eve of war, was the collectively authored Frustration and Aggression .[72] Intended to test the basic notion that "aggression is always a consequence of frustration," the authors' ambitious goal was to restate psychoanalytic ideas "quantitatively in the form of a connected set of postulates or behavior principles which have been confirmed by a wide range of facts drawn from laboratory experiments, clinical case studies, social statistics, and anthropological field work."[73] The authors believed this effort had both theoretical and practical value. They aimed to dispel the notion that behaviorism and psychoanalysis were conceptually incompatible and simultaneously provide a psychological framework for the analysis of sociological problems ranging from racial prejudice to political ideology itself.

War was not the least of the social phenomena they wished to explain in terms of aggression and frustration, and in doing so, the members of the Yale group were simply following Freud's clear lead. Social progress of any kind required massive efforts to repress hostility, as Freud had argued in Civilization and Its Discontents (1930), and the costs in personal happiness were steep enough to constantly threaten modern civi-

lization with reversion to a state of unrestrained violence and barbarism.[74] In his famous exchange of letters with Albert Einstein, Freud equated the task of eliminating war with the challenge of advancing civilization itself. Both rested on the shaky foundation of repression.

There is no use in trying to get rid of men's aggressive inclinations. . . . For incalculable ages mankind has been passing through a process of evolution of culture. . . . We owe to that process the best of what we have become, as well as a good part of what we suffer from. . . . The psychical modifications that go along with the cultural process are striking and unambiguous. They consist in a progressive displacement of instinctual aims and a restriction of instinctual impulses. . . . Whatever fosters the growth of culture works at the same time against war.[75]

In the early years of the Yale Institute, even its sympathetic Rockefeller Foundation funders worried that such socially oriented goals as analyzing the roots of bigotry and warfare would generate storms of criticism for being insufficiently scientific.[76] Less than a decade later, following U.S. entry into World War II in 1941, Rockefeller Foundation officer Alan Gregg told Yale Institute director Mark May, "I did not see that the Institute was open to valid criticism since the psychological element in the present war was such as to make psychological studies of an importance that could not be disputed."[77]

Thus institutionally strengthened and intellectually vindicated by the outbreak of war, the Yale academics involved themselves in an ambitious Social Science Research Council plan to summarize, for the use of government policy-makers, research on the social effects of war, including studies of the family, minority groups, crime, and all varieties of morale.[78] One of the Yale Institute's projects that proved militarily useful during the war was an ambitious data bank called the Cross-Cultural Survey (later incorporated as the Human Relations Area Files). Started in 1937 by anthropologist George Peter Murdock with the aim of keeping comprehensive files on four hundred of the world's most representative "primitive" cultures, the project was greatly expanded by the navy (which gathered lots of information about Pacific societies) and the coordinator of inter-American affairs (who kept track of Latin America).[79]

Many psychologists found the formulation of Freud's frustration-aggression theory offered by John Dollard and his Yale colleagues to be a compelling, not to mention timely, explanation of international events. Gardner Murphy approvingly cited Frustration and Aggression and wrote, "Fighting in all its forms, from the most simple to the most complex, appears to derive from the frustration of wants. . . . Satisfied

people or satisfied nations are not likely to seek war. Dissatisfied ones constitute a perennial danger."[80] What, after all, could possibly be more aggressive than war?[81]

Frustration and Aggression embodied many of the basic assumptions commonly accepted among psychologists. Even those not inclined toward Freudian theory could agree, on scientific grounds, that individual and collective behavior alike consisted of discrete adjustments that could be scrutinized methodically, if not experimentally. But Frustration and Aggression also represented a step toward a unified and integrated basic science of human behavior that, in expert hands, could handle with ease the complicated business of diagnosing and treating society as the patient. As John Dollard pointed out, scientific experts should be recruited for these delicate, but critically important tasks, if only because

life would be unbearable in a world where one was constantly having to choose. Uncertainty is exhausting and choice demands special psychological strengths and reserves. It is, therefore, a human necessity that the world be, to some extent, predictable. Behavior must flow along at least some of the time in golden quiet. Man needs orderly knowledge, scientific knowledge, a kind of knowledge which permits him to act most of the time without the excruciating necessity of choice.[82]

No experience illustrated better than war what could happen if behavior did not "flow along at least some of the time in golden quiet." By exposing the irrationality of motivation, the unpredictability of behavior, and the capriciousness of mass attitudes, World War II reinforced the psychological experts' faith in themselves and increased their confidence that even shaky psychological theories could guide public policy better than popular will or the conventional wisdom of diplomats. Conveniently, war also gave these experts an opportunity to operate outside the ordinary constraints of democracy. This precious and, they believed, temporary freedom was at a maximum in the military, especially in the area of psychological warfare.

The Sykewarriors on German National Character

The "sykewarriors" of the Psychological Warfare Division (PWD) of SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Force) operated directly under the command of General Eisenhower.

Their assignment was to reach and persuade enemy minds: "to destroy the fighting morale of our enemy, both at home and on the front."[83] Not only did the overall Allied goal of unconditional surrender present endless frustrations to the sykewarriors (it severely limited their ability to persuade through positive incentives), but the PWD experts also had to live with an unsavory reputation among the military brass as a bunch of professorial "characters," "administratively irresponsible symbol-manipulators," and "unsoldierly civilians, most of them needing haircuts, engaged in hypnotizing the enemy."[84]

The PWD efforts to understand the German civilian and military mind relied heavily on the concept of national character and the assumption that Germany was a sick patient, experiencing a psychological episode traumatizing enough to require a thoroughgoing suppression of rational attitudes.[85] On the basis of such theorizing, Henry Dicks, a British psychiatrist associated with PWD's intelligence division, developed a questionnaire for use in POW interrogations.[86] Designed to elicit a range of attitudinal responses about National Socialism, Hitler, and so forth, the results were converted into a series of German personality types, demarcated according to different psychological responses to Nazi authority. Drawn exclusively from German men of military age, the aggregate data were generalized to German society as a whole.

1. fanatical "hard-core" Nazis (10%)

2. modified Nazis "with reservations" (25%)

3. "unpolitical" Germans (40%)

4. passive anti-Nazis (15%)

5. active anti-Nazis (10%)[87]

On the basis of this distribution, psychological warriors predicted the responses of various German groups to Allied propaganda. This particular effort to track military and political developments via analysis of individual personality was considered so successful that a U.S. psychiatrist, David M. Levy, was called in to organize a "personality screening center" even after SHAEF was dissolved.

As an example of psychology deployed for military purposes, the POW study was certainly important. It was as important, however, for its working assumptions: that political ideology was, at best, partially rational and conscious, preferably understood as an expression of deep personality structure; that the life history, and especially experience in infancy and childhood, provided the most accurate guide to individual

character and social behavior; that the concept of national character was reliable enough to produce systematic ways of addressing frustrations, which in turn produced discernible national patterns in everything from childrearing to educational philosophy.[88] The many experts working on morale widely shared these hypotheses and applied them as readily to the content analysis of captured documents, print, and broadcast media as to in-depth interviews with POWs. The notion that individual personality development, political ideology, and cataclysmic social events like war could not be understood apart from one another was a characteristic feature of their theoretical approach.

The PWD experts believed that their psychological operations would shorten the war and, toward that noble end, they built a track record of genuine creativity that included artillery-fired leaflets, newspapers dropped by bombs, and a "talking tank" that made persuasion a literal element in combat. In spite of the ceremonial accolades they received at the end of the war ("Without doubt, psychological warfare has proved its right to a place of dignity in our military arsenal," wrote General Eisenhower to PWD Brigadier General Robert McClure), they were perplexed about why the real decision-makers, from FDR on down, had paid little if any attention to them in determining overall war policy.[89] Such cavalier neglect of psychological expertise, they warned, would be terribly unwise in the future. Behavioral experts, they felt sure, would shortly supplant both diplomats and soldiers in the very dangerous world to come.[90]

The Sykewarriors on Japanese National Character

What PWD did for Germany, the Foreign Morale Analysis Division (FMAD) of the Office of War Information (OWI) did for Japan. Sponsored by the OWI in cooperation with the Military Intelligence Service of the War Department, FMAD grew directly out of the experience of the Sociological Research Project at the Poston Relocation Center for Japanese-Americans. Alexander Leighton directed both projects, and the FMAD analysis of Japanese morale was based on the very same "fundamental postulate" about human nature that had animated the earlier effort to make the "psychiatric approach in problems of community management" indispensable to administrators.

The thirty or so analysts who staffed FMAD made their first task to seek out exploitable cracks in the fighting spirit of the Japanese military,

widely perceived to be unstoppable, even fanatical. Their study of Japanese national character, based on the same sorts of data used by PWD, pointed to the same soft spots in morale: powerful irrational and weak rational motives, perceptual distortions, and the likelihood that whatever individual autonomy existed would be corrupted through contact with crowd sentiment and behavior. FMAD concluded, as PWD had, that since emotional forces were of greater salience than conscious political ideals in motivating Japanese soldiers, psychological warfare strategies that rationally attacked Japanese imperialism or calmly advocated democratic ideals could have had few if any positive results. Emotional appeals had a far more dramatic effect.

Of particular importance, they found, was the emotional role of authority, and especially the image of Japanese emperor Hirohito. Direct attacks of any kind on the emperor, however cathartic they might be for Americans, were unlikely to lower Japanese morale and even threatened to backfire by rallying the Japanese military around a highly emotional symbol. "One cannot," Alexander Leighton and a colleague warned, "successfully attack with logic that which is not grounded in logic."[91] FMAD experts considered this finding, and the eventual policy decision to allow the Japanese emperor to remain on the throne, to be among the greatest political successes of wartime behavioral experts. For them, it proved that the psychological approach to policy was an extraordinary scientific advance over the dubious, if conventional, reliance by policy-makers on mere intuition or the whims of personal experience. There was, however, little evidence to show that the many confidential studies of Japanese character FMAD did for the War Department, or similar studies for the State Department, actually affected this important policy decision.[92] Indeed, had the experts been clearly heeded in this case, and had Truman announced early on a U.S. willingness to allow Hirohito to continue as emperor, it is possible that the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki could have been avoided.

The foundations of Japanese civilian morale were just as emotional, with roots in distinctive childrearing, eating, and schooling habits. For example, it was suggested that "weaning trauma" frequently coincided with the arrival of siblings, fast meals recapitulated the denial of infantile needs for pleasure, and teachers smothered competition and enforced strict obedience among students—all contributing factors to an aggressive Japanese national character. Contrary to popular U.S. opinion that Japanese resolve was unwavering, FMAD research showed a sharp decline had already begun in Japanese civilian morale that would eventu-

ally lead to surrender. Reports like FMAD's "Current Psychological and Social Tensions in Japan" suggested that anger, aggression, displacement, apathy, panic, and hysteria were highly sensitive elements in Japanese national character, and ought to be as significant as food shortages and economic pressures in the calculations of military planners.[93]

The Strategic Bombing Survey on German and Japanese Morale

At the war's end, many FMAD staff participated in the Strategic Bombing Survey's Morale Division.[94] Its ambitious postwar study, designed to answer the question of whether and how aerial bombing had affected German and Japanese morale, was directed by psychologist Rensis Likert, previously head of the Division of Program Surveys, Bureau of Agricultural Economics, U.S. Department of Agriculture. In this government bureaucracy, which appeared to be located very far from the heart of military policy-making, Likert and his staff had pioneered the incorporation of intensive interviewing and research survey techniques as a routine part of large-scale government surveys intended to keep tabs on wartime public opinion.[95] The psychologists who participated in the Strategic Bombing Survey's morale study included Dorwin Cartwright, Daniel Katz, Otto Klineberg, David Krech (previously Krechevsky), Ted Newcomb, and Helen Peak. Virtually all of them were members of the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI), the most important organizational nucleus of wartime social psychology.[96]

Immediately following the German surrender, the morale experts began to collect some four thousand interviews. In Japan they conducted some three thousand interviews during the last six weeks of 1945. Plagued by familiar time and personnel shortages and faced with daunting logistical difficulties, they generated the same kinds of national character studies and collective personality profiles that outfits like PWD and FMAD had done during the war, as well as a handy, quantifiable "Morale Index" and comprehensive final reports.[97] The results generally showed that aerial bombing, while dramatic, had not had nearly the effect on morale that U.S. policy-makers had expected would be the case, a conclusion readily championed by participants, like

Alexander Leighton, who felt it vindicated the wartime predictions of FMAD and other psychological warfare think tanks that enemy morale had begun an irreversible slide toward surrender.[98]

Intelligence

Intelligence gathering comprised another critical component of work in the psychological warfare field. Intelligence did not necessarily require firsthand espionage, and the term often described the analysis of national character from a distance. The OWI's Bureau of Overseas Intelligence, for example, was headed by Leonard Doob, a psychologist affiliated with the Yale Institute of Human Relations. Its Washington research staff numbered around one hundred, with branch offices in New York and San Francisco. This outfit shared much of the general approach, already outlined, to psychological warfare. Its work disseminating "propaganda" to enemy countries and "information" to allied and neutral countries drew inspiration from national character studies and attempts to identify the strengths and weaknesses in enemy morale.[99]

The OWI Bureau of Overseas Intelligence also shared most of the headaches of other sykewarriors, especially in trying to get policy-makers to appreciate the advantages of allowing psychological experts a determining role in the policy-making process. According to Doob, the work of his researchers was used when it suited the interests of policy-makers and ignored when it did not, an indignity Doob attempted to remedy by spending the latter part of the war hobnobbing with high-level policy-makers and functioning as a marketer of behavioral research.[100] Although a true believer in the enlightening potential of psychological expertise, Doob admitted that he found the decision-makers as irrational as the bureau's German or Japanese research subjects.

He [Doob, referring to himself] had learned the valuable lesson, as frankness increased his frustrations, that he would be more valuable as a social scientist and happier as a human being if he treated almost every individual like a psychiatric patient who had to be understood in the gentlest possible fashion before he could be expected to swallow the pill of research. In the Overseas Branch, this meant being pleasant to what seemed to be millions of people—which, for this writer, was quite a strain.[101]

Firsthand intelligence gathering was the main job of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the predecessor and model for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which was established by the National Se-

curity Act of 1947. The OSS Psychological Division, organized in September 1941 and directed by University of California psychologist Robert C. Tryon, was staffed by eighteen psychologists.[102] A few names have been released, but the identities of individuals affiliated with the division beyond 1942 are still considered confidential for reasons of national security.[103]

The division's own mission statement, "Role of Psychology in Defense," envisioned an ambitious morale program at home as well as abroad, supplemented by a variety of highly classified special projects. Although it had an even more top-secret image than other morale agencies, the OSS Psychological Division used the very same conceptual tools (national character) and data-gathering methods (surveys, polls, and in-depth interviews). It also called upon the same civilian consultants and professional networks for aid: officers of the APA and the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI), to mention but two examples. The OSS frequently used a farming-out method, in which key mediators, like Harvard psychologist Gordon All-port, would identify psychological experts with special skills, from foreign languages to inside knowledge about German colleagues. "The OSS interest in the problem should remain a secret," Robert MacLeod reminded Allport, "although you would be free to let it be known that your findings would be communicated to the government."[104]

The selection of intelligence agents was another critically important service provided by psychological experts to the OSS. Like many other activities in the field of psychological warfare and personnel selection, the OSS selection procedure was constructed with German psychology in mind. American experts were all too aware that their German counterparts were ahead of them. Highly effective methods of officer selection had been developed throughout the Nazi period, creating "an unprecedented type of organization for human engineering."[105] But the Americans were unwilling to be beaten at their own game. "America should have no qualms about adopting some of the best features of German military. psychology," they argued, since "the Nazis have unblushingly expropriated the findings of many American scholars."[106]

The OSS assessment staff, whose driving forces included Henry Murray (an eclectic physician, psychologist, and psychoanalyst) and Donald MacKinnon (a psychologist), devised the most elaborate and thorough procedures in the entire U.S. military. The three-and-one-half-day ordeal included cover stories to disguise personal identity, simulated enemy interrogations, psychodrama improvisations, and a variety

Figure 3. Group Rorschach used by the Office of Strategic Services for

selection purposes during World War II. Photo: National Archives

of objective and projective psychological tests (fig. 3).[107] This enormous investment of expert time and attention was certainly due in part to the perception that the stakes were very high; those selected after the lengthy ordeal would play key wartime roles. But it was also due to the fact that selection requirements for the OSS were more confusing than the measurement of particular skills or aptitudes, which was the standard requirement in most branches of the U.S. military. The personal qualities and talents necessary for a good intelligence agent were unpredictable, at least compared to those of a good aircraft mechanic, as MacKinnon admitted when he noted that "nobody knows who would make a good spy or an effective guerrilla fighter. Consequently, large numbers of misfits were recruited from the very beginning."[108] The "assessment of men" (also the title of the 1948 book which documented the work of the OSS team) "is the scientific art of arriving at sufficient conclusions from insufficient data."[109]

Like other wartime experts, the OSS assessors believed they were making a patriotic contribution and taking advantage of a golden opportunity to upgrade science at the same time. Where could they have

found a more perfect place to aid the war effort and simultaneously validate personnel selection technologies? In later years, some of the OSS experts had lingering doubts about their wartime activities. Henry Murray, for example, chief of OSS Selection Station S, was transformed into a militant pacifist and peace activist after the U.S. dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, thought the OSS should be disbanded completely, and strenuously objected to the establishment of the CIA.[110] Donald MacKinnon, on the other hand, went on to institutionalize the OSS selection procedures at the Institute of Personality Assessment and Research at the University of California, whose goal was nothing less than "developing techniques to identity the personality characteristics which make for successful and happy adjustment to modern industrial society."[111]

For the most part, policy-makers whose own agendas did not include the scientific or professional advancement of psychology were not disturbed that the interests of nationalism and science conveniently converged during the war for their expert counselors. They were impressed by psychologists' work, content to benefit in tangible ways, and more than happy to leave the theoretical debates to the experts. In 1945, when Congressional hearings were held to determine if scientists' wartime contributions had been sufficient to win them a national foundation of their own (a process that eventually culminated in the founding of the National Science Foundation), much testimony, such as the following, was offered by military planners about the usefulness of OSS psychological activities, in personnel selection as well as in psychological warfare.

In all of the intelligence that enters into the waging of war soundly and the waging of peace soundly, it is the social scientists who make a huge contribution in the field in which they are professionals and the soldiers are the laymen. . . . The psychological and political weapons contributed significantly to the confusion, war weariness, and poor morale on the enemy's home and fighting fronts. There is no doubt that operations like these shortened the war and spared many American lives. . . . Were there to develop a dearth of social scientists, all national intelligence agencies servicing policy makers in peace or war would directly be handicapped.[112]

Such public declarations proved that psychology's accomplishments were real as well as imagined, at least insofar as reality was assessed by those in a position to further the status and funding of psychological work. There was certainly no shortage of testimonials from policy-

makers that psychological experts were indispensable to the successful execution of war in the fields of human management, enemy morale, and intelligence. Experts' patriotic fervor, practical skills, soothing insights, and flair for self-promotion all convinced many policy-makers charged with military and national security planning that psychological talent would be equally necessary in future periods of war and peace. The wartime record of those psychological experts who worked on the home front, on questions ranging from U.S. public opinion and military morale to the psychology of prejudice, is examined in the next chapter.