12—

Coronado and Imperial Beach

Description of the Area

Silver Strand Littoral Cell

The segment of coastline extending from the entrance of San Diego Bay southward to beyond the International Border between the U.S. and Mexico is known as the Silver Strand Littoral Cell. This cell has its own northward transport path and zone of deposition. The principal natural source of sediment for this cell is the Tijuana River. The accretion area zone is in Zuniga Shoal and directly offshore of this zone (Inman 1976:40).

Coronado was once a combination of two islands, with a swampy area between them. The swamp is now entirely filled with sediment brought by the Navy when the large base was established to the south. There is a long spit coming from the embayment of the Sweetwater and Tijuana rivers, and inside this an extensive delta has built up much of the land, extending as far south as the Mexican border (fig. 94).

Figure 95

View of the Coronado sand spit looking south, 1898.

Photo: U. S. Grant IV collection.

Figure 96a

January 1905 view of Hotel Del Coronado.

Photo: F. Shepard collection.

Zuniga Jetty and the Building of the Hotel Del Coronado

In 1888, the Hotel Del Coronado was built at the northern end of Coronado on a poorly developed sand spit (fig. 95). In 1893, construction began on a 7,500-foot-long jetty on Zuniga Shoal, intended to stabilize the entrance to San Diego Harbor. This rubble structure, located west of the hotel, was completed in 1904. Erosion problems developed on the spit immediately following construction of the hotel, and a small stone breakwater was built to the southeast, in 1897, to offer protection from wave erosion. It was damaged and repaired at a later date.

Erosion of the beach occurred just west of Spanish Bight in 1900, following extension of the Zuniga Jetty. Railroad tracks northwest of the jetty had to be relocated in 1901. Erosion continued during the next extension of the jetty in 1903–1904, which took it farther east of Spanish Bight. Severe storms beginning in January 1905 caused erosion both north and south of the Hotel Del Coronado (figs. 96a , 96b ). On January 4 and again on February 18, waves focused on the hotel area, necessitating the installation of 30,000 two-hundred-pound sandbags. February and March storms continued to cause serious wave erosion, and a total of 110 feet of land was removed by the waves along Ocean Boulevard (fig. 96c ); the houses left undamaged were subsequently relocated to downtown San Diego. Between 1905 and 1908, a 5200-foot-long seawall was built from the hotel west along Ocean Boulevard.

In recent years, over thirty million cubic yards of sand have been dredged from San Diego Harbor (Shaw 1980). One million of that was deposited north of the hotel and sixteen million was deposited to the south, which greatly widened the beach. Subsequently, construction of huge condominium apartments has dominated the spit south of the hotel and down through Imperial Beach (fig. 97).

Figure 96b

February 1905 view of the same site as that in 96 a . Note the severe erosion of the beach cliff and that

approximately 30,000 two-hundred-pound sandbags had been placed north and south of the hotel, in

order to save it from destruction by the waves.

Photo : F. Shepard collection.

Figure 96c

March 1905 view looking south from the Hotel Del Coronado. The photo was taken following severe sea

storms which eroded approximately 110 feet of beach and cliff sediment to the north of the hotel.

Photo : Center for Coastal Studies, SIO.

Figure 97

View of condominiums recently constructed on the Silver Strand Coronado sand spit, 1980.

Photo : M. Clark, Center for Coastal Studies, SIO.

Figure 98

"Silver Strand littoral cell showing the Tijuana River as the

former natural sand source, the littoral transport path north

along Silver Strand, and the depositional areas or sinks.

The final sink for sand in this littoral cell is the offshore area

indicated by the isolines of sand accretion determined by

comparisons of surveys in 1923 and 1934." From Inman 1976:41.

Figure 99

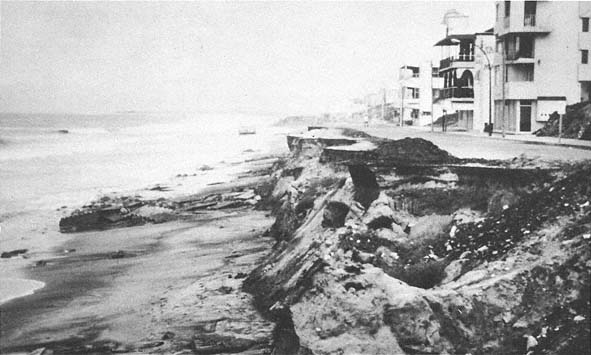

View along the beach at Tijuana, 1983. Note the severe erosion of the beach and road.

Photo : C. Everts.

Imperial Beach Erosion

Erosion at Imperial Beach has been an increasing problem since 1953, even during the drought periods preceding the recent floods of 1978 to 1980. It was during this earlier dry period that sand became unavailable to the beaches because dams had been built on the Tijuana River Basin. Inman (1976) indicates that approximately 660,000 yards of sand per year would have normally reached the beach, if not entrapped by these dams. As it actually happened, however, the beach had to be artificially nourished by dredging. Between 1945 and 1967, this sediment had moved north from Imperial Beach to the Zuniga Shoal area, indicating a predominantly south-to-north longshore current during this period (fig. 98).

By contrast, weekly observations made by Shepard (1950) for about a year in the late 1940s showed a more variable direction of the current. At the south end of the beach, the currents were predominantly south to north, while in the northern portion, they were largely north to south, with the exception of an intermediate point at the northernmost station. Shepard also found that currents near Zuniga Jetty were more commonly south to north in the summer (fig. 3) and north to south in winter, as would be expected from the wind direction during the varying seasons. The cutting away in recent years of the broad beach at the condominium apartments may indicate yet another change in direction of the current. During the early part of the winter of 1983, the beaches south of the border were severely eroded, and the sediment apparently moved north, accreting in the Imperial Beach area. Since construction of the Rodrequis Flood Control Dam on the Tijuana River in Mexico, the beach cliff has eroded markedly for at least three miles south of the border, and all construction along the shore, including the highway, is disappearing as this is written (fig. 99). It is obvious that the currents in the area are quite complicated.

For some time there has been much discussion about cutting another entrance into San Diego Bay, near the south end, so as to have a second channel

to the sea in case the main entrance becomes blocked by earthquakes or military activity. This also would give access to boats from the south. One of the difficulties with the second entrance idea is that it would probably decrease the tidal current at the main entrance, which would result in deposition such that dredging would become necessary. Before constructing a second entrance, Imperial Beach should consider the various marinas being maintained along the coast: these all require jetties that have considerable influence on sediment transport.