PUBLIC FACES

Chapter Two

The Nature of Civic Individuality

The word moka (from the Sanskrit mukha) or face was heard frequently in conversation. It stood for a person's image before others and for his self-respect. It was one of his most important possessions.

M. N. Srinivas, The Remembered Village

Before we can understand the community of George Town and examine why it is organized in the manner that it is, it is necessary to understand the nature of civic individuality and the highly personalized nature of social relationships in south Indian society that make identity so important. Reputation, public trust, eminence, and the roles charismatic community leaders play are all associated aspects of civic individuality. What I am talking about is how relationships are formed and things accomplished, and the role that individuality plays in daily life.

Even today, when the growth of cities and the spread of bureaucracy might lead one to expect that relationships would be increasingly depersonalized and that anonymity would be on the rise, south India remains a highly personalized society. By highly personalized, I mean that, beyond the limits of kin and friends, personal relationships are important determinants of how one conducts one's life. A Tamil's success in life vitally depends on maintaining good relationships and a good reputation within one's community.

To be successful in daily endeavors in Tamil Nadu society—say in running a small business or in seeking employment—a person must be trusted. This means either being well known to others, so that they know personally what to expect of the person, or being known to the leading men and women of the community, persons whose reputations are known, so that they can vouch for the individual to those who seek to estimate him or her. For example, lenders will give credit only to those

they know repay their loans, and employers hire only those for whom they or others they trust can personally attest. This need to be known is different from American society where individuals rely much less on personal knowledge and much more on bureaucratic indicators of reliability, such as credit ratings, certification, or, as the request goes, a "picture i.d. and a major credit card."

In India, as in all societies, peaceful interaction requires that people behave for the most part in predictable and reliable ways. Law, enforced by sanctions external to relationships, is one source of reliability; trust, embodied within relationships themselves, is another. In south India, trust still has a major role. An Indian evaluates the degree of trust he or she has in the reliability of a relationship in terms of knowledge of the other party or parties in that relationship. A reputation is the public sense of one's responsibility for one's identity and actions, an assessment of responsibility for past behavior.

One important factor in such an evaluation is the reputation of the other party as a civic individual. Is the other known to be a "good person" and a trustworthy individual, for example? A second factor is the strength and nature of the relationship the parties have, including how enduring and important the relationship is to the parties involved. The underlying assumption is that if a relationship is important to a person, that individual will act in a reliable manner because it will be in his or her self-interest to preserve the relationship. Again, we see here that the Indian view preserves the sense that individuals are responsible for their own actions. Finally, a third factor is whether or not the other party is known to persons of eminence and is vouched for by them. A man or woman of eminence is a person who has an enduring and highly prized relationship with his or her community,[1] one that is defined by the prestige and status the person has achieved in that community. The actions of such men and women are circumscribed by the collective interests that define their prestige and constrain their statuses. Consequently, it is very much in the self-interest of eminent persons to preserve their eminence by vouching only for those they trust. If a person for whom they have vouched betrays their trust, it is in the eminent person's interest never again to act as a guarantor on the betrayer's behalf. This fact is well known in India. It should be clear, therefore, that reputation, eminence, status, including offices, achievement, and responsibility for how one behaves and who one is are highly valued features of identity, defining a person's civic individuality in Indian society.

It should also be clear that eminent individuals play key roles in the regulation of trust within communities. For an ordinary person, known to a limited circle of individuals, it would prove difficult to establish ties of trust that reach beyond the circle without the validation of eminent persons. An eminent person is known much more widely. Indeed, the greater one's eminence, the greater the circle of individuals among whom one is known and can act as a guarantor of reliability. A Tamil's circle forms the context of his or her civic individuality and delimits its spatial dimension.

I remember once sitting in a jeweler's showroom in George Town, the business center of Madras City, chatting with a prominent diamond merchant, when a Viswakarma, or goldsmith, came in. This particular merchant had recently shown me a diamond and gold necklace worth, he told me, $90,000. It certainly looked like it was worth that much. It was a heavy piece with several courses of diamonds. One of his Indian customers living in New York had ordered it made by him, and he was preparing the customs papers for mailing the necklace, which was why, he said, that he had it in the shop rather than under lock and key elsewhere. The merchant had a few goldsmiths who worked at the back of his shop, but according to business custom, most of his work he put out as piecework to artisans who crafted the jewelry in their homes, some as far afield as Bombay. Goldsmiths are poor artisans on the whole, and I remember being impressed that merchants, such as this one, trusted their artisans with gold and gems worth sizeable sums, although not so much as this necklace.

The goldsmith who had entered the shop explained that he was a skilled gem-setter and was looking for work. He was very polite in his demeanor and speech, and in reply, so was the merchant. The merchant explained to the goldsmith that he had no work for him but would keep him in mind. After the goldsmith had left, the merchant said to me that he would never hire the man. I asked if he knew him personally. The merchant replied that, while he did not, he knew his name and reputation. Some time ago the goldsmith had stolen gold he had been given to make a piece of jewelry and had fled Madras. When he had spent what he had stolen and was again looking for employment, he found that no one was willing to hire him in his new locality because he was unknown to jewelers there. As his situation became more desperate, he returned to Madras, but now found that no jewelers would hire him there, either. The merchant explained that he, like other jewelers, never

hired a man whom he did not personally know or for whom another trusted jeweler would not or could not vouch. Effectively the goldsmith had been blacklisted, and it was unlikely that he would ever again work as a goldsmith.

I asked if the police had been called regarding the theft. The merchant laughed. There was no advantage in that. Calling the police meant that you would lose twice, once from the theft and a second time from the police, who would require bribes. Basically, the jeweler felt that the merchants' network offered a more effective means of dealing with theft than the police.

The jeweler's sentiment is widely shared. The effectiveness of relying on personalized relationships to regulate behavior in India's cities is attested by the low rates of urban crime, despite high rates of poverty, compared to U.S. cities. For example, with a population of about 12 million people, one third[2] of whom live in slums, Calcutta recorded less than 100 homicides in 1990, compared to New York City's 2,200 (Karl E. Meyer, New York Times , Jan. 6, 1991). One Calcutta newspaper editor bragged, "You are safe in the parks. We've had one notorious rape there in 20 years" (Karl E. Meyer, New York Times , Jan. 6, 1991). Similarly, in Madras, with a population of 4.2 million in 1981, 15,693 crimes were recorded for the year (India Today , 66). This represents a crime rate of one crime per 267.6 persons, although the number of crimes is undoubtedly underreported. This rate compares with one crime per 5.9 persons[3] in 1986 for the university district surrounding my own University of California campus, where underreporting is also common. In the university community the crime rate is forty-five times higher than that of Madras.

Low crime rates relate to neighborhood solidarity and stability. Urban crime rates in India are highest in the new residential suburbs of India's biggest cities. In 1961, before substantial suburbs had been developed in Madras City, the crime rate was one crime per 463 persons, almost half of what it is today.[4] In the old residential areas of an Indian city, the individual has very little anonymity. If a man is not known, people ask who he is, or they note things about him so that, if it interests them, they can follow up on finding out about him. On several occasions I have seen an Indian note the license plate number of someone who has piqued their interest, their intent being to find out who the person is. A week later, through private enquiries, they know. I myself have found that all sorts of Madrasis have known me by my license plate number. It is clear that individuality—expressed here as being known—is con-

sidered important in urban India today, and that a reputation for good character and ability is highly prized.

The "Big-Man" Versus the Bureaucrat

It would be misleading, of course, to suggest that bureaucracy plays no role in Indian society. In fact, its role is a major one. The police, law and the courts, voter registration and elections, driver's licenses, taxes and fines, examinations and university degrees, bank accounts and applications for loans are familiar components of bureaucracy that regulate the lives of Indians. In contrast to trust based on personalized relationships, bureaucracy depends on depersonalized criteria for determining reliability. For example, a bureaucratic method of determining financial honesty is by rules of accounting that judge honesty by criteria defined in law. A man's civic individuality—who vouches for him, what his relationships are, and what his reputation is—is much less relevant, although it may weigh in decisions about hiring or about how to prosecute law breaking. However, in a trust-based relationship, honesty and reliability are evaluated in terms of who a person is. With no direct monitoring, a trusted person has considerable leeway in the use of resources that he or she might control in common trust, that is, so long as that trust continues.[5] The point to be made is that bureaucracy diminishes the importance of individuality and of personalized relationships, whereas in a society that bases reliability on relationships of trust, the importance of individuality, namely, who a person is and what a person does, is stressed.

In a trust-based society, when persons who control desired resources, commodities, and services need to choose who is to get what, then the identity of the individual seeking a benefit and the influence of the people he or she knows can be the critical factors determining how choices are made. For example, a seller often must choose to whom among several potential buyers he will sell, and a banker has to decide to whom to lend money. Under such conditions, knowing eminent persons, people south Indians often refer to as periyar , big-men, can obviously be very beneficial. Here I use the term to include influential women, although the reader should keep in mind that their comparative number is quite small. Big-men can wield great influence among members of their communities, because people perceive them as being able to act as brokers on their behalf. The civic attention of the community focuses on the individuality of big-men when community members accord prestige to these community leaders, a public recognition that distinguishes their

singularity and agency. These are the individuals who make things "happen" for their followers. By contrast, bureaucracy is designed precisely to circumscribe the influence and agency of individuals by depersonalizing the operation of institutions.

A south Indian friend of mine, whom I shall here call Tambi, related the following story about trying to start a business in Madras that reveals the juxtaposed roles and different styles of the bureaucrat and the big-man in south Indian business and banking. The story has deeper implications than simply how to get a loan in India. It suggests that there is a close relationship between the role of the individual as an agent and the organization of south Indian society. This is a relationship I shall explore in detail in the chapters that follow.

Tambi and three of his friends met as engineering students at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Madras. When they graduated they decided to start a small industry in Madras City, manufacturing tubular aluminum furniture, an industry that depends heavily on marketing. To finance the initial capital required, Tambi went to his elder brother, Annan, who is himself a wealthy and well connected businessman in Madras. The brothers are members of the Nagarattar caste, a well-known business and banking caste in south India, which also has extensive business ties with Southeast Asia (cf. Rudner 1989). In addition to the businesses that Annan runs in Madras, he is the director of a large textile mill in Kerala and has ownership interests in rubber estates and financial institutions in Malaysia. Annan maintains close contacts with the business moguls of Tamil Nadu, many of whom are also Nagarattars. This he does in part by his active membership in the Cosmopolitan Club of Madras, a men's club that is an important meeting place for the state's business and government elite. Annan also maintains his ties by going on pilgrimage to Kerala to worship the god Aiyappan with a group of his influential Cosmopolitan Club friends every December/January. Pilgrimage groups of this sort are a common feature of the Aiyappan festival, and the shared experience intensifies the sense of fellowship among group members. Members maintain their pilgrimage group year after year.

At the time that Tambi approached him, Annan had an interest in a private lending society, Frontier Investments,[6] a business that was owned by the father of two of his classmates. Annan arranged for Tambi and his partners to borrow Rs. 10,000 on a hundi contract, a short-term high-interest promissory note, that stipulated that at the end of three months they would return Rs. 12,000. This was an agreement that required a high rate of profits for the fledgling industrialists. Each partner also con-

tributed Rs. 1,000. The partners' plan was to use the Rs. 14,000 to finance their fixed capital, but they still needed a place to manufacture. For the time being they rented a small house on the outskirts of the city, but the structure was inadequate for their needs, and, moreover, they lacked adequate working capital.

Tambi then discovered that a new shed was being built at the Guindy Industrial Estates in Madras, which he thought would be ideal for their needs. The problem was how to win the lease. The estates are an established development run by the state government, and Tambi and his partners knew that competition for the lease was bound to be fierce. Again they approached Annan. One of Annan's friends was a deputy director in the Department of Industries and Commerce, which administered the leases in the Guindy Estates. Annan told the four young men to take their application to him. Subsequently, they succeeded in obtaining the lease, although there were several other qualified applicants for the shed.

With their fixed capital and lease secured, they now approached the branch of the State Bank of India attached to the Industrial Estate and explained to the loan officer there that they had their own fixed capital and were seeking a working capital loan. The State Bank, a state-run bureaucratic institution, administered a special scheme for industrial development. They required that applicants be university degree holders whose application demonstrate that they had a viable project. As graduates in engineering, and with Tambi's elder brother's charter accountant's help, the partners had no trouble writing a convincing application. They got the loan. Their successes up to this point were a result of a combination of personalized contacts and appearing to meet bureaucratic regulations. However, without Tambi's elder brother's personal connections, the four partners would have lacked sufficient fixed capital and the manufacturing shed, and so would not have qualified as a reliable risk for the working capital loan under the bureaucratic criteria used by the State Bank. The State Bank loan officer was also unaware of the high-interest hundi loan, which in fact meant that the partners' enterprise involved very high risks.

Surprisingly, in the year that followed the partners managed to keep their business afloat, and, seeing their success, Annan personally took over the hundi loan at year's end, allowing the partners to reduce their interest payments. Financially, things were beginning to look better, but profits were still slim. By the end of that first year, the four realized that it was going to take time to develop their market before they could expect to make any real money. All but one decided, therefore, to go back to grad-

uate school in engineering. The exception was the partner who had been managing the business. He decided to enter management school instead.

The business continued for three more years, each partner attending school and contributing to the business in his spare time. They managed the business out of their dorm rooms on the lit campus. When at last they all graduated, the manager, who had been talking to some of his management friends, decided to leave the business and to go to Bangalore to begin a new business, which he thought would earn him "big" money. The departure, however, was a tense one. The manager told his partners that they owed him back pay for his four years as manager. Shocked, Tambi told him that if he insisted on back pay, they would sue him for having ruined the business, since it was running at a loss at the time. To give force to his threat, Tambi told the manager, "Go see my lawyer." The lawyer was in actuality a good friend of Tambi's, and also happened to be the son-in-law of one of Annan's partners. The reader should notice how Tambi's access to Annan's veritable "cat's cradle" of social connections begins to emerge.

The manager decided to leave peacefully. However, unbeknownst to his partners, he went to the State Bank before he left and told the loan of-ricer there that he was leaving the business and that, since he was the only one of the four who knew how to run it, the bank would be well advised to call the partners' loan. When the partners next tried to make a withdrawal from their capital account, they found that it had been frozen and the loan recalled. The partners' financial situation was desperate.

After several months of looking for a bank that would finance a capital loan, the three partners again approached Annan. In response, Annan arranged for Tambi to meet with the chairman of the Bank of Madurai, a large private bank founded and controlled by Nagarattars. Annan knew the chairman, and like many other Nagarattars, he conducted his business banking through this same bank. Without Annan's connections, Tambi says he would never have been able to arrange to see the chairman.

Tambi arrived at the meeting prepared with an accounts summary of his business. Annan explained Tambi's situation to the chairman, and then Tambi and the chairman talked informally "across the table." Tambi described his need for a loan to pay off and replace the one that the State Bank had recalled. To a banker, of course, the State Bank's refusal to continue the loan was very damaging information because it indicated that after four years of business the bank judged the partners a bad risk. This simple fact was the reason the partners had been unable

to get another bank to consider a loan. The chairman, knowing this, also knew Tambi's brother Annan and that Annan was a reliable businessman of recognized stature in his own right who kept his business accounts at the bank and also happened to belong to his own caste. There is a common sentiment among prominent men of a caste that a leader owes it to his community on occasion to extend a helping hand to his caste fellows. Bonds are created that benefit both, the benefactor gaining a loyal supporter and the beneficiary receiving the benefaction. After a short chat, the chairman told Tambi to talk to his branch manager and that "everything would be done."

Reflecting on why he got the loan, Tambi told me that he thought being a Nagarattar was important. "Most people working in the bank are Nagarattars," he said, "and if a Nagarattar with a degree knows someone working in the bank, he can get a job there. A couple of my cousins work in the bank." Also critical was the fact that his brother had a strong, established relationship with the chairman. Had he been judged purely by bureaucratic criteria, Tambi is certain he would never have gotten the loan. Subsequently, the chairman helped the three partners with additional loans, including capital loans for machinery. As a result, the business has grown and is now quite successful.

The account of Tambi and his partners reveals not only contrasts between how bureaucratic and trust-based relationships work, but also how trust-based relationships link up with and center on men of influence, "big-men." Consider the organization of the relationships used to acquire the Bank of Madurai loan and the agency of the individuals involved. The chairman enacts the role of a preeminent big-man, that is, a man who can make things happen because he controls an institution that distributes resources and services to a clientele. He is also a big-man because he wields substantial influence among prominent men, such as Annan, who are less powerful than he. In contrast to men of Annan's stature, relationships among preeminent big-men tend to be highly competitive; they do not help each other. Instead, they try to outdo one another, each seeking to achieve the reputation of being first among the preeminent. Annan, by contrast, plays the role of one of the chairman's lieutenants; he is a subordinate big-man because, while he has influence and can affect the outcome of events, his influence is less than the chairman's. He needs people like the chairman from time to time. Indeed, because he is a beneficiary of the chairman's influence (he benefits as a banking patron and by being able to help his brother), he may be counted a member of the chairman's clientele. At the same time, as a man "with

connections," Annan also has his own constituency that incorporates Tambi and his two partners among others. In turn, Tambi is a member of the constituencies of both Annan and, through him, the chairman. Finally, Tambi's connections make him the benefactor of his partners, who in turn are members of his constituency. The relationships joining the men are in each instance unequal and are based on personal rather than bureaucratic ties.

The hierarchical interlinked nature of all of these relationships and how to work them is well understood by all the parties involved; consequently, they go largely unstated. People recognize that the chairman is a big-man because of his preeminent power and control of desired resources, and out of his earshot people will call him a periyar . By contrast, "lieutenant," "constituent," and "clientele" are my terms, which I am using to ease the reader's understanding. My informants, while they have an intimate sense of the relationships these terms label, including the subtleties of relationships involved and the degrees of power represented, do not use these terms to refer to one another. Instead, they talk about a person's connections with big-men—how good they are—and who a person knows. They also appreciate a man who helps them and imbue him with eminence because he does. Eminence is the basis of a man's prestige and all Tamils, particularly men, strive for it. And eminence is graded: the eminence of powerful persons who have large constituencies is greater than that of persons who are less influential. A direct measure of eminence is the institutions that a person heads or is an officer in and the size of the population that these institutions serve.

The Individual as Focus of Organization

In Indian society, pivotal persons such as periyar exhibit a special form of public individuality, which I call an "individuality of eminence,"[7] because public recognition of a leader's uniqueness stems in part from the fact that the leader ranks first among his or her followers. This kind of individuality is expressed in part by the special influence and autonomy that leaders have within groups and by their abilities to distribute benefits and command others to do their bidding. The individuality of leaders, therefore, is not that of one unique person among many similar unique persons, as some characterize Western egalitarian individualism. Rather it is a type that is marked by the superiority of leaders over their followers. In the West, leaders often seek to identify themselves as one

among their constituents, as expressed in the U.S., for example, by the presidential phrase, "My fellow Americans." By contrast, in Tamil society, leaders are recognized as self-interested patrons who rank above their constituents. Leaders use their constituents who in turn use them.

The individuality of eminence is associated in Tamil Nadu with a special type of group formation, the "leader-centered group." This kind of group is an association that forms around a central figure, a man like the chairman, and his subordinate lieutenants, men like Annan, and is maintained by ties of relationship that link the central leader to all members of his group. The preeminent big-man of such a group is always the controlling officer of corporate institutions that he uses to distribute benefits and attract a clientele. A few of his subordinate lieutenants will be junior officers in these institutions and will serve only him. Others, such as Annan, lack offices in the preeminent big-man's institutions, but are persons who bring clientele into his constituency because of their own personal relationship with him. Lieutenants like Annan may have ties with several preeminent big-men, just as a big-man's ordinary clients may also maintain ties with several preeminent men. A big-man serves different sets of clientele with each institution that he controls. Consequently, the total constituency composing a leader-centered group is an aggregate of his lieutenants, the separate constituencies attracted by each of these lieutenants, and the distinct clientele served by each of the preeminent big-man's separate institutions.

Although leader-centered groups are themselves not corporate, the institutions that the preeminent big-man controls usually are. Nonetheless, these too are the organizations of their central leader, and when that leader dies or grows too old to command, often they decline or splinter into new leader-centered institutions, each organized around a new central figure and his personal following. This pattern is typical of a range of institutions, including joint families, caste associations, community charities (Mines and Gourishankar 1990), cooperatives (Mines 1984), and political parties in Tamil Nadu today.[8] This pattern is also true of privately owned banks such as the chairman's, if to a somewhat lesser degree, despite the direct bureaucratic control over banks exercised by the central government. For example, consider how who the chairman is (a member of the Nagarattar caste) and knows (Annan, himself a Nagarattar) has affected how he conducts business (favoring Nagarattars) and whom he employs (again, Nagarattars). Should the bank fall into the hands of a non-Nagarattar, for example, bank policies will change,

just as who the new chair knows and relies upon will change, whatever the new chair's caste may be.

A key expression of a Tamil leader's individuality is the leader's public reputation. In Tamil society, the reputation of a respected leader is somewhat paradoxical. Eminent leaders are often economically successful, reflecting their skill as pursuers of self-interest. However, to avoid accusations of venality, a leader must circumscribe his or her successes with a reputation for altruism, honesty, and a commitment to the collective good of the community. In other words, a leader must achieve a reputation for behavior that is in effect a denial of self-interest. Yet, leaders also want people to know that it is they who are altruistic. A leader's patronage is not given anonymously, but publicly, with the knowledge of his community. It is to commemorate their altruism that community leaders typically engrave their names on the stairs and walls of temples, marriage halls, charitable societies, and libraries. They also publish their names and sometimes their pictures in the posters, announcements, invitations, and book-sized souvenirs that are associated with public events in order to make known who they are and to advertise their individual responsibility for deeds done for the benefit of their public.

Achieving simultaneously a reputation for both success and altruism is difficult because the two are seen as contradictory. Consequently, it is no surprise that the more successful a leader is, the more he or she will be accused of venality and corruption. This helps to explain the highly acrimonious nature of leadership in south Indian society.

In Tamil culture, the archetypal way a leader establishes a reputation for altruism is through patronage and involvement in institutions established to serve the interests of a constituency. By acquiring offices in such institutions and rights to symbolic honors associated with them, leaders dramatize their eminence and place themselves at the center of a clientele that they seek to serve. Competition for offices and honors is a part of the achievement strategy of leaders and would-be leaders alike.

In sum, the individuality of Tamil leaders lacks the characterizing values some scholars (e.g., Dumont 1970a) have associated with Western individualism, notably equality and liberty, which are associated with the sense of the individual as an equal among equals.[9] Nonetheless, the identity of leaders does exhibit several other features of socially significant individuality, including individualistic social identity defined by public reputation, uniqueness marked by eminence, achieved identity associated with a deliberate striving after one's own gain, dominance and prestige, and autonomy marked by responsibility for who one is and

what one does. This form of public individuality, the individuality of eminence, therefore, rests on a recognition of achievement and of the individual as an agent.

Kasi’s Story: A Tamil Big-Man Explains His Civic Identity

I interviewed "Kasi," Kasiviswanathan, in his home in 1979, in the town of Trichengode, which is located in the western dry zone of interior Tamil Nadu. The town is a pilgrimage site because of its famous Saivite temple, dedicated to Ardhanariiswarar—Siva represented in a half male, half female form. The temple offers a dramatic sight, located on the top of a giant rock at the town's edge.

Born in 1912, Kasi was sixty-seven years old at the time of my interview and still very much involved in public life. He belonged to a Tamil weaving caste, the Kaikkoolars, and was well known in the region as a caste and political party leader.

As a younger man, Kasi had been a follower of the famous Tamil independence leader, "Rajaji," C. Rajagopalachariya, and until his forty-fifth year, was the president of the taluk (subdistrict) Congress committee. The Congress was the leading party of India's independence movement and the dominant political force in Tamil Nadu until the mid-1960s. I had been told by acquaintances of Kasi's that I must go to Trichengode just so I could meet him. Kasi was recommended to me in this manner because his friends considered him an important man, a man of accomplishment, one of the big-men of his caste. In their recommendation, his acquaintances described to me features of his individuality: his importance, offices, and reputation for past actions. Stressing Kasi's eminence, his friends emphasized his individuality.

When I interviewed Kasi, we met at his house. It was after lunch and the atmosphere was quiet; most in the household were taking their afternoon naps, as is the Tamil custom. On the wall was a signed photograph of Jawaharlal Nehru, dated 1929. Kasi had the relaxed manner of someone who had been interviewed many times before, but he seemed happy to be of service to me for a few hours.

When I begin a life story interview, I usually start by asking my informant about family—his or her parents and siblings, date of marriage, children, their education and what it is that they are doing today. Completing this section of the interview, I next ask my informant about himself or herself.

Kasi had a precise sense of what it was he needed to tell me so that I would know who he was and what he did and had done. His approach was identical to the way I had heard others describe themselves when they, like Kasi, had achieved some degree of eminence. He related to me first his status as the head of his family and family businesses. Next, he listed his current civic offices, and then he described the institutional offices that he had held earlier in his lifetime.

He said that he was the proprietor of all his family's businesses, meaning by this that he was still the head of his own joint family. He and his wife lived with their second son, while his three other sons lived separately. Nonetheless, all five men together managed the several enterprises that they jointly owned under Kasi's proprietorship. Kasi also ran a textile sizing business, which he owned in partnership with one of his brothers.

Kasi next described to me the offices he currently held in various civic institutions. At the time of the interview, he was headman (naattaanmaikaarar ) of the Kaikkoolar caste council in Trichengode and the joint-headman of the caste's territorial council for a region incorporating seven cities and their surrounding village hinterlands, known as the Seven City Territory (Eeruurunaadu). Trichengode was the territory's headquarters. In other words, Kasi was telling me that he was one of two preeminent caste leaders for the seven cities area. Next, Kasi said that he was the president of seven religious institutions and the president of a committee that collected construction funds for the Trichengode Government High School. He told me the committee had already built eleven rooms for the school, three in his family's name. When Kasi spoke of his family's name, he meant his name as family head. He had also built under his leadership and in his family's name a marriage hall for his caste, which was located in front of the rock temple, an auspicious location. He said ten to thirty marriages were conducted there by his caste fellows every year. Finally, he said, he was also a member of the Trichengode Rotary Club, an association that kept him in touch with all the associations in town. He kept his finger on the pulse of local events, he said, and remarked that his second son had been the joint secretary of the Junior Chamber of Commerce the previous year.

Next Kasi described civic offices that he had held in the past. Until 1977, he had been the vice president of the statewide handloom weaver's cooperative society, Cooptex, an important post. A friend, caste mate, and close political ally was the society's president. Kasi had also been a member of the state's Handloom Board for ten years and director of

three cooperative spinning mills, located in Salem, Tirunelveli, and Srivil-liputtur. And he had been the director of the Cooperative Union in Tamil Nadu, which is an advisory board to the government on production cooperatives. Finally, as mentioned above, when he was younger and had political ambitions, he had been the president of the Congress Party Taluk Committee.

At the time, I remember realizing that Kasi's purpose in describing his institutional offices was not simply to list his accomplishments for me, but primarily to describe his role as an institutional leader with multiple constituencies, some small, some large. His description reveals the contextual nature of civic identity and its spatial dimension, which expands and contracts in relationship to the size of a leader's constituencies. Over time, the size of the populations Kasi had served had changed substantially. Once he had been a state-level leader. Until his retirement from Cooptex in 1977, Kasi had served a statewide constituency that he had helped build. The handloom textile cooperative movement took its inspiration from Mahatma Gandhi and was until 1977 controlled by members of the Congress Party, which used it for the distribution of largess and the building of grassroots support. In those days, the handloom weaving industry was the largest category of employment after agriculture in the state, and so Cooptex appealed to what was theoretically a significant pool of potential political supporters. Throughout the state under Cooptex auspices, local leaders founded or managed production cooperatives, which tapped into the statewide association, enabling them to enact roles as patrons within their local weaving communities. Kasi told me that when a weavers' housing colony was built in Trichengode with Cooptex support, it was named after him, although he himself had favored naming it after Rajaji. As president of the Congress Party Taluk Committee, therefore, and vice president of Cooprex, Kasi was for a time a patron of statewide influence and eminence.

In 1979, when I interviewed him, Kasi was a leading townsman and regional caste leader serving a much smaller constituency. As co-headman of the Seven City Territory, he shared his preeminence as a caste leader with only one other man. That night, following the interview (see Mines 1984), I had the opportunity to observe Kasi in his role as headman during a council meeting that the leaders and representatives of the subcouncils of the territory attended. Kasi sat on a raised dais surrounded by the subordinate headmen and representatives of the Seven City Territory, and when I entered the meeting room, I had an immediate sense of his power. He was a chief among his lieutenants, a man with

the power to outcaste or impose fines on any local council that failed to adhere to Kaikkoolar caste rules regarding the governing of councils. That night the council of one of the towns that had been outcaste by a previous action came to plead for readmission. Symbolic of its submission, throughout the discussion of the case, a servant of the council lay prostrate on the ground, his arms outstretched before Kasi and his fellow Eeruurunaadu Council members.

Yet the caste council was only one of the many institutions within which Kasi held a preeminent role at the time of the interview. The other associations he described himself as heading were what Tamils term charitable institutions. The constituencies of these institutions—the seven religious institutions, the school building fund committee, and the caste marriage hall—were much smaller than that of the caste council. Each of these institutions, however, enabled Kasi to play the role of patron. As patron, Kasi cast himself in the role of an altruistic leader dedicated to the service of his community, his clients. He told me that he had donated Rs. 30,000 to the school building fund. Through these many institutions Kasi built for himself a grassroots political constituency, based on his personalized relationship with the circles of clients associated with each of the many institutions he managed.

Listening to Kasi describe himself, I realized that his intent was to make clear to me his public self. He was telling me that his eminence, his institutional roles, and his influence among others distinguished him. These features define Kasi's "civic individuality." Kasi even described his identity within his family in these terms, stating that he was the head of his joint family and proprietor of all his family's businesses. It also became apparent that having control over decisions affecting himself and others, an ability which is associated with statuses of eminence, was an important feature of his individuality because control gave him autonomy.

When a person such as Kasi describes his civic identity, his telling is filled with implied authority, but it is also always impersonal, revealing little about the inner man. This impersonality is a distinguishing feature of the way Tamil men express the civic dimension of their individuality. It was later, when I asked Kasi about his personal goals and dreams that he told another story, the story of his motivations, hopes, and disappointments. In his telling, he revealed himself as an idealistic young man who had entered politics in the heady days of Mahatma Gandhi, Rajaji, and the Indian Independence Movement. Kasi personally bad known Rajaji. He told me that politicians then were motivated by ideas and ideals, while today politics is "all personalities." Politicians no longer

care about ideas. He regretted the years he had spent as a politician after Independence was achieved, and he was disgusted with modern politicians. He felt betrayed by them.

The layered way in which Kasi reveals his identity is typical of men who have achieved some public eminence in their lives: First they tell of their civic identity. It is later, when they are questioned about their goals and aspirations, that they reveal the private dimensions of their lives. Civic lives and private selves are not, then, two separate identities. Kasi has a sense of himself within society and a sense of how others know him. He also has an inner awareness of himself. Each of Kasi's senses of who he is affects the other. Personal talents and abilities, private desires, hopes, and disappointments drive motivations and give force to achievement in civic life. They energize its drama and pathos. They lie behind the manifest public individual. (Tamil descriptions of the inner self are the subject of chapters 7 and 8.)

Finally, it must be noted that Kasi did not describe his individuality in opposition to groups, but rather in terms of who he was and what he did within groups. In this context, it is important to distinguish between Kasi's civic identity and what Dumont labels a collective identity. In the latter case, the person has the identity of his or her group. In Kasi's case, his identity is his own, but it is an identity that is built on his eminence within groups, an aspect of his contextualized identity.

The Community and the Individual

The examples of the goldsmith, Tambi, and Kasi illustrate the importance in Tamil society of personalized relationships and of leader-centered groups, configurations of interaction that require a close connection between organization and individual agency. But just how important are the agency of leaders or the actions of ordinary persons as influences on the way urban communities are organized and integrated? Part of the answer lies in how civic individuality is valued. I have suggested that eminence implies a community that shares values, as does reputation. What, then, is the relationship between these values, which are features of the interaction between individuality and community, and the formation and dynamics of an Indian urban community? Or, put differently, what does an Indian urban community took like, and how does its appearance reflect this interaction between shared values and individual interests and agency? And finally, just how important are communities, castes, and individual identities in a large cosmopolitan Indian city today? What are

the motivations and involvement of ordinary citizens in community, and what are the currents of change?

I argue in the chapters that follow that the relationship between individual and community has been historically dynamic in India, and that, as circumstances change, individuals rework their relationships with their communities. In the process, they transform the meaning of both citizenship and community. Leaders are important agents of this community transformation. Forever competing to enlarge their constituencies, they must from time to time redefine what they consider their own interests in light of changing circumstances and adjust how they make their appeals to ordinary citizens to suit.

The roles and motivations of individuals are reflected not only by the organization of urban relationships but also by an urban community's very structure and layout. I take as the focus of my study the old walled town of Madras City in Tamil Nadu, south India, the area of the city that is today known as George Town. I argue that the organization of George Town reflects the history of a series of Indian solutions to the problem of how, in the highly competitive context of commerce, to guarantee trust and reliability in relationships. What the organization of the urban community shows is that the freedom of the individual is always circumscribed by an ethic that sets the standards by which the civic individual in different roles must behave in order to establish trust-based relationships. Individuality is not eliminated by this imposition of constraints on behavior but, rather, is emphasized, although emphasized differently from the way it is in the West.

Chapter Three

Institutions and Big-men of a Madras City Community

George Town Today

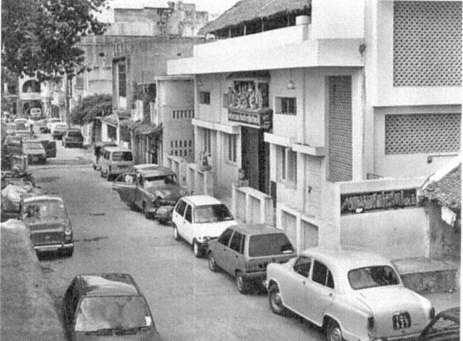

George Town and Fort St. George, just to its south, are the oldest parts of Madras City (see map 2). One can still see fragments of the old wall fortifications that once circumscribed and protected George Town, while the fort still has its walls and traces of its moat. The fort must be entered through heavy iron-studded doors, which remind the visitor of the uncertain peace of former times. Within the old walled area of the Town the streets are narrow, often choked with every sort of vehicle, cycle rickshaws carrying boxes of freight, small children on their way to or from school, and sometimes men holding great sheets of metal, which they have purchased for purposes unknown to the observer, slowly being pedaled among the crowds; there are brightly painted lorries, hand-pulled carts, bullock carts, bicycles, scooters, automobiles, and auto rickshaws buzzing about the Town's outer edges, trying to avoid getting stuck in the traffic jams. Pedestrians clog the streets' remaining spaces.

The Town is the financial center of Madras. American Express has its office here, and so does the Madras Stock Exchange. The Town is where the descendants of Madras City's oldest banks are located; it is also a center of informal banking. The big moneylenders, the "shroffs" of old, dealers in bullion and cash, operate here, so too, the Cashiers, the Kasukaarar,[1] the accountants of the big banks and enterprises. George Town is also the business center of the city. Madras harbor lies just across the railroad tracks on the Town's eastern edge. Once there was no harbor, only the open sand beach on which small wooden boats departed and landed through the persistent surf, ferrying goods and people to and

Map 2.

Contemporary George Town and Fort St. George, Madras City.

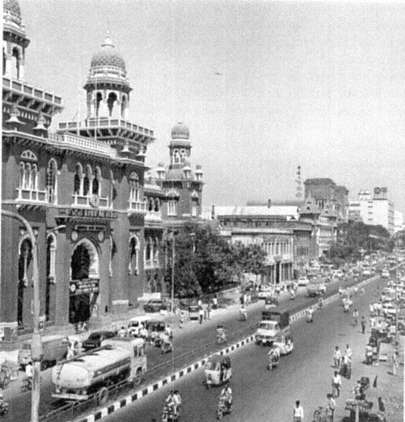

Figure 2.

A view along First Line Beach Road. The photo was taken from the

roof of the Beach Railway Station. The large building on the left is the local head

office, State Bank of India, formerly the Imperial Bank of India during the colonial

period. George Town, 1992.

from ships anchored at sea in the "Madras Roads." Today, Madras has an artificial harbor, which is fitted to receive the giant container ships that ply international waters, although one can still see ships like tiny dashes on the distant horizon, "standing" in the roads waiting their turn in the harbor. For convenience, the Custom House and the General Post Office, the city's main post office, are located near the harbor on North Beach Road, now renamed Rajaji Road.

As the city's business center, the range of enterprises, large and small, located in the Town area is extensive: jewelers, gem dealers, book sellers and publishers, moneylenders and bankers, wholesalers and retailers

of iron and steel, nonferrous metals, textiles, fancy feathers for the fly-fishing industry, fireworks, electrical goods, leather, pharmaceutics, locks, and metal hinges—the list is enormous. Several of the oldest business houses, houses whose names reflect their British colonial past, have home offices here: Binny's, Best and Crompton, Castrol, Parry's, Gordon Woodroffe. This area of the Town, just across from the harbor, is called Muthialpet. Mannady, the adjacent area to the southwest, is considered by old residents to be an integral part of the Muthialpet neighborhood. Popham's Broadway, running north and south, marks the western edge of this eastern section of George Town.

Across Broadway, inland and to the west, is the old community of Pedda Naickenpet, although, today, this area, too, is subdivided. The northern section is still called Pedda Naickenpet, but the southern section is now called Sowcarpet. North Indian Hindu and Jain merchants live here in large numbers, and south Indians say that they feel transported to north India when they step into these streets. Sowcarpet is where many of the big moneylenders, gem dealers, and some of the Tamil-speaking goldsmiths live and operate. The buildings are mostly old houses to which one or two stories have been added over time. On the narrow veranda of one, a goldsmith and his three assistants manufacture 22-karat-gold bangles and necklace "chains." Nearby, a Jain gem dealer sits resting against a long white bolster, talking quietly to another man, his wooden desk cum money-box by his side. Large sums of money change hands in these modest surroundings.

At its heart, Sowcarpet incorporates the city's main green grocers market, Kothawal Chavadi, where I once bought one hundred limes for Rs. 2, about U.S. $0.26 at that time. Business is so intense here that wholesalers rent shop space by the hour. A single shop may have several tenants operating in series, each for a few hours, through the course of the twenty-four-hour day.

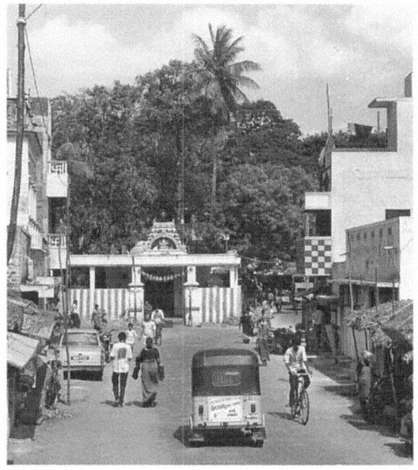

Just to the south of Sowcarpet is Park Town, famous for its jewelers and iron merchants and the location of George Town's most popular temple, the Muttu Kumaraswami, or Kandasami temple.[2] This is the temple to which I was going on a rainy night in September 1985, to begin my fieldwork in George Town.

It was my plan over the next ten months to study leadership and individuality among two of the Town's prominent castes, the Beeri Chettiars, one of the foremost merchant castes of the Town, and the artisan caste once named the Kammaalans (Smiths),[3] now usually called Acharis or Viswakarmas. The Beeri Chettiars had been close associates

of the British, from the founding of Madras in 1639, up to Indian Independence in 1947. I had chosen the Viswakarmas because they, like the Beeri Chettiars, had once been a leading caste of the left-hand section of castes in Madras City. Their historic rivals were the castes of the right-hand section, especially the famous merchants, the Komati Chettiars, the community that owned and controlled Kothawal Chavadi. While these once bitter rivalries and the left-hand/right-hand moiety division that framed them are now memories, and although today's descendants of these castes pride themselves on their friendly relations, the history of Madras is marked and shaped by riots and competition between the two factions. The area east of Popham's Broadway, Mannady and Muthialpet, was once the territory of the left-hand castes, the area to the west, Pedda Naickenpet, the territory of the right-hand castes. What legacy had this old division of the Town left behind to shape the civic communities of today?

A few days before my first night of fieldwork, I had been discussing my research intentions over tea with an acquaintance, C. Gourishankar, and his friend, "Babu." Babu, recently retired, had volunteered that one of his former colleagues at All India Radio was a Beeri Chetti who also happened to be the head managing trustee of the Kandasami temple in George Town. I asked him if he could help me contact this man. I thought he might make a good starting point for my research.

Babu made the arrangements. We were to meet with his former colleague, Tiru P. Balasubramaniyam ("Bala"), at the temple office a few nights later. Babu had explained my interest to Balasubramaniyam, and he, "Bala," had indicated that he would try to have present at the meeting a few knowledgeable older men of the community.

Although it was beginning to rain, the three of us—Babu, Gourishankar, and I—managed to find an auto rickshaw willing to take us to the Town. It was dark and wet when we arrived at the temple. We left our sandals at the sandal concession next to the temple's main entrance and entered through the Raja Gopuram, the kingly tower that faced onto the street. High on the tower's face a neon sign depicted in Tamil the word "Ore," the primeval sound of meditation. Inside, the temple was stone and cement, cavernous; we made our way toward the back, past a video shop selling religious films, to the office. Several men, all Beeri Chettiars, sat around a table. Along one wall were large steel cabinets, marked with sandalwood paste and vibuti , symbols of Siva.

Over the next two hours, Bala and his associates spoke rapidly, sometimes singly, sometimes several at once, so that it was all that I could do

Figure 3.

Rasappa Chetti Street showing the Kandasami temple entrance tower

or Raja Gopuram. George Town, 1992.

simply to follow what was being said, let alone take the kind of notes I wanted to. In those two hours, this small group of men outlined what they thought I should know about the Beeri Chettiars of George Town. They told me about the Kandasami temple, its history, and why it was important to the Beeri Chettiars of George Town. They told me the names, families, and brief particulars of who in their memory had been the leading men of the Beeri Chettiar community before families had begun to move away from the crowds and congestion of George Town.

Figure 4.

Kandasami temple roof line.

The list included bankers, the cashiers of important British companies, a lawyer politician, and several very wealthy merchants. A few leaders had belonged to families in which sons or sons-in-law had succeeded fathers and fathers-in-law as influential men. I could tell that everyone present knew of these men, including the non-Beeri Chettiar friends who had come with me, even though some of the leaders had been dead for decades. Among those present, there was a shared sense of the George Town Beeri Chettiars as a community distinguished by who its leading citizens had been. It was also clear that several temples and especially the Kandasami temple figured importantly in both the identity of the community and its leading men. Bala then told me who he was and described the schools and charitable institutions that he had helped found as a leader within his community. Next the men told me a little of the history of the Beeri Chettiars in George Town. It was their sense that the community vitality that had prevailed in their youth was weakening. Families had moved away, and now people often did not even know who their neighbors were. Bala said it was a goal of his, as head trustee of the

Kandasami temple, to reestablish some of the old sense of community. Finally, the men described some of the relationships the Beeri Chettiars had with other temples and other neighborhoods in Madras and surrounding towns. What they were describing to me, albeit in outline, was the identity of their civic community—a community that they saw as threatened, a community that was identified with its preeminent men, its temples, and its institutions—and the relationship to that community that Bala and some of the other leading members of the caste held as individuals. These were the topics upon which my research was to concentrate. They were giving me a quick overview. There are several features of this overview that told me much about the nature and role of civic individuality in Madras today.

When I left the meeting at about ten that night, it was raining heavily and the city was dark. The city lights had failed in the storm and the streets were flooded in places. The normally congested streets of George Town were almost deserted except for a few men wading slowly through the deep puddles.

Exploring the Nature of the "Institutional" Big-Man

Later, thinking about what Bala and his friends had said, I was struck by how personalized their description of the Beeri Chettiars in George Town had been. Names had flown about the room as they had described the caste's past and present distinguished men, the caste's periyar .[4] They had told me which houses had belonged to these men, who they were related to, what they had done, and what their roles in businesses and civic institutions had been. My friend Gourishankar, aged sixty, obviously had known who they were talking about. He had known some of the men when, forty years before, he had attended Christian College, which in his day had been located in George Town. Reflecting on what had been said, I realized Bala and his friends had described their community to me in terms of its big-men and their institutions. I realized that if I were to share their sense of familiarity with their community, I needed to understand what it meant to be a Beeri Chettiar big-man.

In the months that followed, I was to hear informants use a number of terms denoting leaders. I have listed some of these in my previous chapters. In addition to the term periyar , I learned that periyadanakaarar (big-gift-giver) is a related term in a class of similar terms for informal leaders, including talaivar (headman) and ejamaanan (master, headman).

These terms are used to mark the preeminence of persons within their communities and, in some cases of special fame, within the larger society. Mahatma is a similar Sanskrit term, familiar as a designation for Mohandas K. Gandhi, and lexical equivalents of the Tamil terms for big-man are general to Indian languages. In fact, Pedda Naickenpet, the name for the area of George Town west of Popham's Broadway, conveys this same sense of big-man. Pedda is Telugu for "big," and Pedda Naickenpet means the place (pet ) of the "Big Naicken," the title of the headman who used to control this part of the Town in the early years of British East India Company trade. During those early times, in the shadow of the Telugu-speaking Vijayanagar Chiefdoms, the Naicker caste was politically dominant in the locality.

As the head trustee (dharmakarttaa ) of the Kandasami temple, Bala is himself an "institutional" big-man among the George Town Beeri Chettiars. As indicated in chapter 2, I add the "institutional" qualifier to the Indian big-man concept because men like Bala attract followers and enact their roles as generous leaders through the "charitable" institutions that they control.[5] For south Indians, a "charitable institution" is a highly personalized leader-centered association or group that is designed by its founder or leader to benefit a particular clientele, constituency, or community. The leader attracts a following by the benefits he provides. In return, his followers reward him with prestige and an eminent reputation, attributes that give him great influence and discretion among his constituents. When his eminence is great and his institutions particularly effective, then a big-man's reputation also spreads among outsiders. People will know that he is a man responsible for getting things done among his constituents. Like Annan's banker of the previous chapter, an important big-man is a very valuable person with whom to have connections. In Bala's case, the Kandasami temple is one of several community institutions that he heads, but he founds his reputation and so his leadership in these other institutions on his role as the head trustee of the Kandasami temple.

Institutional position is a necessary condition for the viability of the Indian big-man, but it is not sufficient. In keeping with their highly per-sonalized nature, Indian institutions, including temples, expand and contract in popularity and membership depending on the idiosyncratic charisma of their heads. Although it is often supposed that local Indian leaders can depend on ready-made caste and kin constituencies, the fact is that even hereditary leaders have few followers when they lack charisma and skill. Indian society is salted throughout by these "hollow

crowns"—would-be leaders, the heads of associations who have little or no following (see Dirks 1987). In the case of the Kandasami temple, townspeople told me that they thought Bala a particularly effective leader and that the popularity of the temple has greatly increased during his tenure as head trustee.

As I reflected further on my hosts' naming of their community's past big-men, I began to be aware that knowing the names and offices of many people is a concomitant of leader-centered group organization. I sensed that if a person wishes to navigate a fruitful public life in a society composed of such highly personalized institutions, then it is important to know who heads and is responsible for what, as well as who has connections with whom. This is one of the reasons why Tamils keep tabs on so many people. A person who can claim good connections with influential people finds it is easier to accomplish social objectives and to influence others. Knowledge of this sort and the ability to claim connections is valuable and can be misused by dishonest persons. Reflecting this, when much later in my fieldwork I was collecting Bala's genealogy, he suddenly remarked that the information I was gathering could be valuable to unscrupulous persons who might use the information to claim close ties with him. He asked me to be careful to whom I showed it.

Why, then, did Bala and his friends list the past leaders of their community? It was clear to me from the way they spoke of these men that they did so in order to stress that who the George Town Beeri Chettiars are today is in part built upon their community's connections with men of prominence and responsibility from their recent past. They see their community as a composite of families and other associations that big-men head and the connections that exist among these elements, a community centered on eminent persons, their institutions and groups, and on the connections that link them, forever in the making.

Temple, Trustees, Donors, and the Civic Community

A Tamil villager once told me that a community without a temple was unfit for residence. The temple, he said, indicates that the community is graced by the presence of God and that its citizens form a moral community. A community identifies and is identified by others with its temples. Bala and other Beeri Chettiars went to considerable length to explain to me the nature of their community's identification with the

Kandasami temple and the role that big-men played as its patrons and managers. The temple and its functions symbolize the caste community, and publicize its leading associations and who its leading men are. Stories about the temple's history and endowments reveal as much.

That night in the temple office, Bala and his friends described the Kandasami temple as a "denominational" temple, meaning a temple controlled and managed by a single caste community, in this instance, themselves, the George Town Beeri Chettiars. What makes the temple a particularly important institution of big-man leadership among the Beeri Chettiars today is that it is the primary and by far the wealthiest institution controlled by the caste as a whole and, in much the same manner that villagers use their temples, it is used by leaders to represent the caste as a civic and moral community to the world at large. It is also importantly a charitable institution, the caste's central repository of resources that exist for the benefit of the caste as a civic community. An individual who is elected to the managing board of trustees of the temple is elected, therefore, to a position of leadership within the Beeri Chettiar community with control over its main assets. Among the five trustees of the temple, the head trustee, the dharmakarttaa , is preeminent. It is Bala who holds this position. He is the periyar , the big-man, and he is a preeminent figure in his community.

Until 1980, the electorate of the Kandasami temple included only male Beeri Chettiars who lived in Muthialpet, Mannady,[6] and Park Town, but because by that time increasing numbers of families had moved to other parts of the city, caste leaders changed the bylaws of the temple to include in its congregation male Beeri Chettiars living or doing business anywhere in greater Madras City (Madras High Court records). The Madras Beeri Chettiars, therefore, today form the temple leaders' constituency. And this constituency, as a group, constitutes the caste's civic community defined most broadly. But even with this change in bylaws, the Park Town-Muthialpet Beeri Chettiars constitute the core congregation of the temple, and temple trustees have always been selected from among the caste's George Town leaders. It is these leaders who are and always have been the principal donors to the temple and sponsors of temple functions, and it is because of them, and because of the location of the temple, that George Town remains the geographic heart of the Beeri Chettiar's sense of their civic community in Madras City.

Because popular temples such as the Kandasami temple are important institutions of civic leadership, control of them is often contested. In George Town, the leaders of several castes would like to gain special

rights in the temple, and some conspire to dislodge the present temple trustees with this aim in mind. These contenders pursue a variety of strategies, among them bringing lawsuits claiming that members of other castes have made donations to the temple and so, since the Beeri Chettiars are not its sole financiers, they should not be its exclusive managers.

In and out of court, Bala and his allies have countered these pleas, asserting that the caste's right to exclusive control of the Kandasami temple is based on what they argue has been more than three hundred years of unbroken management and on a legend that the temple was founded by two old friends, Velur Mari Chettiar, a Beeri Chettiar, and Kandappa Achari, a Viswakarma man. According to this legend, the two friends were on their monthly pilgrimage to worship Lord Murugan at Tiruporur, fifty-six kilometers away, when they miraculously discovered the idol of Kandasami hidden in an anthill and brought it back to Madras. There, on an auspicious day in 1673, they installed and consecrated the deity in a temple dedicated to the elephant god, Vinayakar, located in the garden of one Muthiyalu Naicken of Pedda Naickenpet. Subsequently, when Mari Chettiar sought to build a temple for the deity, funded in part by his wife's generous gift of her jewelry, Muthiyalu donated the Park Town lands on which the temple now stands. When Mari completed the temple, he handed its management and that of its financial trusts to the "eighteen group" Beeri Chettiars, the eighteen named clusters (gumbuhal ; sing., gumbu ) that composed the Town Beeri Chettiar community at that time. In commemoration of his services, the Beeri Chettiars installed a statue of Marl Chetti near one of the temple's sanctums, where he is worshiped today as a god. Here we see an individual, Mari Chetti, being commemorated for what he had done.

Aside from this legend, lists of donations, and a few undocumented stories, little specific historical detail is known of the temple. Nonetheless, challenges by covetous leaders of other castes to the exclusive control of the temple by the leaders of the George Town Beeri Chettiars have been unsuccessful so far. What historical evidence there is of Beeri Chettiar control has been too strong.

From archival materials, endowment records, and stone inscriptions in the temple we do know that Beeri Chettiar control of the temple is at least two hundred years old. F. L. Conradi's 1755 map (map 3) of "Madraspatnam," as the city was then called, depicts a small unnamed shrine at what is the temple's location today (Love 1913, 2: endpocketmap). We know that the temple was renovated and sanctified as a brick temple in 1780 by the "eighteen group Beeri Chettiars." We know that

Map 3.

Madras in 1755. Based on "A Plan of Fort St. George and The Bounds

of Madraspatnam" by F. L. Conradi.

about 1865 the temple was rebuilt of stone in its present form, and that in 1869 a generous man named Vaiyabari Chettiar donated Rs. 66,000, an enormous sum in those days, to establish a trust to fund various temple functions. He also built the large temple car (teer ) in which the processional idol of the god is carried on the seventh day of the main annual festival (brahmootsavam ). We also know that around 1880 Akkamapettai Govinda Chettiar and Narayana Chettiar donated the land next to the temple for the purpose of building a large community hall, the Spring Hall (Vasantha Mandabam). And we know that in 1901 Kali Rattina Chettiar, a wealthy businessman and the father-in-law of Bala's father-in-law, donated Rs. 50,000 to build the temple's entrance tower (gopuram ) and, in a dramatic gesture still spoken of with awe, gave a cup of diamonds for jewelry to decorate the idol.

Richly endowed, the temple today owns more than sixty houses, most located on prime urban land. The head temple priest's house, which is rented to him by the temple, gives an idea of values. In 1986, its worth was estimated at Rs. 10-15 lakhs (1 lakh equals 100,000 rupees), $100,000 or more at a 1986 rate of exchange. A few of the endowments have been especially grand. The previously mentioned gift of a cup of diamonds and Rs. 50,000 by Kali Rattina Chettiar is one of these, a gift that in those days was worth many times the value of a house. Another is Bala's uncle Venugopal Chettiar's gift to the temple of ten grounds of urban land, which are today the site of a one-thousand-student Beeri Chettiar grammar school founded under Bala's administration. Other endowments sponsor particular festivals; they buy flowers and textiles for rituals and clothes for the deity. Yet others fund building, renovations, and cultural events. Today the temple controls hundreds of millions of rupees in assets.

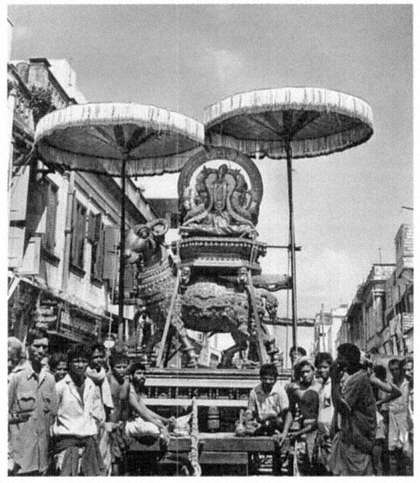

The rich endowment of the temple reflects its popularity and the affluence of the Beeri Chettiars. As a measure of the temple's lively appeal, the temple concession that looks after the sandals of worshipers annually earns about Rs. 36,000 by charging customers a small fee of ten paise[7] for safeguarding their footwear while they go barefoot into the temple. Given that many locals leave their sandals at home when they are going to the temple and avoid the charge, this sum equates with at least 360,000 individual visits to the temple each year. This popularity is especially evident during the Spring Festival (Vasantha Brahmootsavam) when the god, garlanded in flowers and bedecked in gold and diamond jewelry, is taken on lengthy nighttime processions. On these nights, when the processions are longest, crowds gather in the streets for

miles. These crowds are the audience before whom the trustees play out temple pageantry depicting the trustees' role as patrons and the wealth and importance of the Beeri Chettiar civic community.

The temple's rich endowment also reflects the sense each endowment donor has of his or her civic individuality, since endowments state something about who each donor is in relationship to the Beeri Chettiar community: that he or she is an acknowledged member of the community and makes his or her gift in the interest of the caste's collective good. Through his gift, the individual achieves for posterity a respected reputation within the community congregation. Over the centuries Beeri Chettiars, singly and as associations, have made numerous donations, both large and small, slowly building the temple's wealth. Individual donors without children who have left houses and property to the temple are commemorated in inscriptions and posters that list donations. Without descendants, their donations must preserve their identity within the civic community and keep alive a memory of who they were.

A Viswakarma once told me that a person with lots of gold has abundant strength and fertility. So, too, a community. On the night of our initial meeting, demonstrating the temple's wealth, Bala first described the gold ritual vehicles and processional objects possessed by the temple, and then, with the others at the meeting, we left the office to examine them in their locked sheds. He made clear the connection between donors and sponsors and particular ritual objects: the Beeri Chettiar Iron Merchants Association donated the gold crown worn by the processional idol and all the gems that encrust it; the Town's betel leaf[8] merchants donated approximately 2.5 kilograms of gold for the gold peacock processional vehicle (vahana ); the shroff (bankers and dealers in bullion) merchants donated 4.0 kilograms of gold for an elephant processional vehicle. And the Town Beeri Chettiars as a community donated 3.0 kilograms of gold for the processional palanquin of the supernatural warrior-hero and ally of Kandasami, Surabatman.

The temple also has a silver-plated car, strung with colored lights, constructed with temple funds. Temple cars have a pyramidal form, ornately decorated with carvings, temples on wheels. Some are huge juggernauts, towering twenty to thirty feet or more. Electric wires obstruct the passage of these biggest of cars, and today only a few are taken on procession in the city. Others, smaller, are designed to pass below the city's electrical lines. The garlanded and jewel-bedecked idol is carried in the car-shrine during processions, often with priests sitting before it in order to accept and present offerings submitted by worshipers. In

Figure 5.

Gold-plated temple car (teer ) with the Kandasami gopuram in the

background. The processional idol of Kandasami may be seen riding in the car.

1984, in his role as head trustee of the temple, Bala himself built for the temple with temple funds a gold teer plated with 7 kilograms of gold, one of twelve in southern India, and a significant new expression of the temple's claim to importance.

In their opulence, each of these ritual objects declares to all who see or hear of them the vitality of the George Town Beeri Chettiars and ide-

alizes the altruistic commitment to the civic community of the associations and leading citizens who gave. Of course, everyone recognizes that the objects also make great advertisements for the donors and the Beeri Chettiars as a community and boost reputations. Bala and the others were showing me that the Kandasami temple is regarded by the Beeri Chettiars as a key institutional symbol not only of their community as a whole, but also of its leading citizens and associations.

Temple Processions, Community, and the Eminence of Leaders

If the temple is a symbol of the community, then the temple's builders and the officers of the temple and its events are key agents of the community. They take responsibility for the community's image and in doing so draw attention not only to the community, but also to their own individual importance within it. Without leaders, there is no community; without a community, there are no leaders. Civic leadership and community go hand in hand.

During festivals and important times of worship, which are collective community events, temple trustees and other leading citizens among the Beeri Chettiars enact ritual roles that single them out and publicly dramatize their eminence as instrumental individuals within their community. During a special worship, for example, the sponsor stands closest to the deity among the spectators and acts the role of a dignified but humble host to important guests and spectators (fig. 6). South Indian culture values the leader who is generous, who acts on behalf of his followers. The leader's actions and position near the god mark him as responsible for the event and indicate that he is important. It will be known that he is responsible for accomplishing things in other social arenas as well. Should he show special respect to others while enacting his ritual roles, this recognition confers on them public prominence. The sponsor's civic individuality, therefore, is expressed partially by his eminence and his seemingly selfless agency, his status as a temple trustee or as a sponsor of a ritual event. After the worship he will receive tokens of special respect from the head priest, marks of honor, such as a large quantity of prasadam (food "left" by the god) that he can distribute, in recognition of his instrumental role as sponsor. When a temple event is important, great prestige is attached to these symbols of respect because they indicate a man's significance within his community, and for all the outward appearance of altruism, the reality is that leading men compete bitterly to achieve or protect rights to them. By the mechanism of his own re-

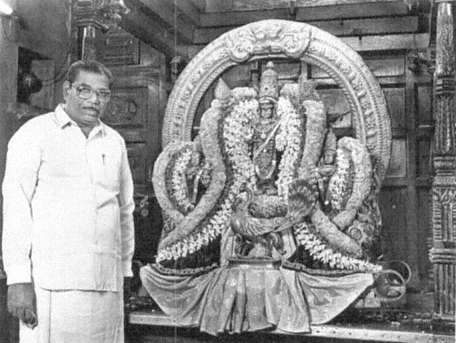

Figure 6.

Tiru P. Balasubramaniyam, head trustee or dharmakarttaa of the Kandasami

temple, shown here with the decorated processional idol of Kandasami, who is flanked by

his two consorts. The humble demeanor of Bala is characteristic of a sponsor of worship.

George Town, 1992.