Six

Marking the Center Festivals and Legitimacy

Since Copernicus man has been rolling from the center toward X.

The nihilistic consequences of the ways of thinking in politics and economics, where all "principles" are practically histrionic: the air of mediocrity, wretchedness, dishonesty, etc. Nationalism. Anarchism, etc. Punishment. The redeeming class and human being are lacking—the justifers—

Nietzsche, The Will to Power

The Bolsheviks seized power in the name of an ideology that deplored centralism. Yet after the coup an attack on central authority constituted an attack on their own power. Root contradictions that underground existence had left dormant—for example, party discipline and popular initiative, revolutionary iconoclasm and central authority—could no longer be ignored. Revolution and Civil War were not times to wallow in moral vacillation, nor were the Bolsheviks given to public introspection. Yet the question of just what the party represented demanded debate and resolution. In the end principles that had united the prerevolutionary party and inspired the Revolution—for example, egalitarianism and pacifism—were discarded. How could this be the same Bolshevik party? How could it maintain authority when it violated the ideals that first legitimized its power?

The Bolshevik identity was woven of many strands. There was Marxist ideology, which Lenin and his colleagues had digested and adapted to Russian conditions; it proclaimed the proletariat the class of the

future. There was the revolutionary underground, where a core of elite revolutionaries had formed and developed a conspiratorial modus operandi. There was the Civil War, when many whose allegiance to Marx and the party seemed temporary had joined. Revolutionary exigency held these strands together, but many alliances formed during the Civil War could not be permanent. In the summer and fall of 1920, when victory seemed closer than it ever had, the Bolshevik leaders began reinstating the tight discipline essential to a stable party identity. They had to choose, by calculation or by reaction to onrushing events, what the Bolsheviks ultimately were: what was incidental to the party and what lay at its center.

Revolution had fragmented Russia's centers of power. The mythic sources of Romanov authority were cast in fatal doubt; the Provisional Government was torn apart by a duality of power. Even the Bolsheviks' first social models separated the political from the cultural centers. Ideology, power, culture, and society stood apart. The center—the source of power—was adrift, waiting to be seized; if the new regime was to stake an uncontested claim to the country's destiny, it would not only have to drive opposing forces from its soil, which it was about to do, it needed to claim the symbols of the center.

Finding the center—the core—of the party's identity was made all the more critical because it was instrumental to maintaining political power. Authority, as Edward Shils notes, is deemed most legitimate, and is most secure, when it radiates from a society's "central value system."[1] It can then claim an inviolable sacredness (or its secular equivalent), which exacts the unconditional subordination of all other values and claims to power. Shils and Clifford Geertz, following Max Weber, find "charisma," the ineluctable impression of "standing in a privileged relationship to the sources of being," the main attribute of the center.[2] Charisma is concentrated in a place, institution, or person that embodies and projects the structure of power.

Several emendations must be made to the notion of center before it can describe the fluidity of revolutionary Russia. According to Shils and Geertz, the center is expressed by rituals and symbols, which embody root "values and beliefs" (Shils formulation). The assumption of consonance among symbol, entity, and values, which is often justified, did not hold during the Russian Civil War. The symbolic center could be the true seat of power, as the Kremlin under Stalin would be, but it could also stand apart from the institutions of political control. The symbolic center was a separate dimension of power that supplemented institutions and ideology. In fact, in Civil War Russia it was often inconsistent

with them. A profound ambivalence animated revolutionary symbols and spectacles. Atheism and sacredness, egalitarianism and hierarchy mixed freely; worker holidays were celebrated by marching from the proletarian outskirts to the government center; a regime seated in Moscow projected its mythic origins to the heart of imperial Petersburg.[3] The center was dynamic, mobile, shifting; the Bolsheviks did not so much have to attach themselves to the center as to fix it in one spot.

The elusiveness of the center comes from a paradox of origin: power is conferred by the center; yet the center is created by power. Power generates a logo-center, the illusion of origin, a fixed point that prevents the onset of chaos and allows for meaning and hierarchy. This essential attribute of the center, noted (ironically enough) by Jacques Derrida, creates the right to name, to fix the principles of a society.[4] The Bolsheviks demonstrated some awareness of the problem in 1918, when they expended considerable effort to ensure the proper interpretation of their festivals. They understood what this relatively minor issue represented: the right to speak for the nation and thus to govern it. To rule the country, they had to speak for it; to speak for it, they had to project a common origin.

The Bolsheviks' program did not mandate the absolutism that had become standard practice by 1920. They had come to power as egalitarian democrats who promised to convene the Constituent Assembly and end the war. They consequently dispersed the Constituent Assembly and plunged the country into a civil war that destroyed its economy and killed many of its citizens. The traditional source of party identity, Marxist ideology, did not justify such a program, which actually isolated the party from the masses. Only the growing sense of historical mission that animated the party could serve as justification. It made the most despotic policies seem the instruments of divine ordinance, separated the Bolsheviks from all other parties on Russian and foreign soil, and embraced classes and groups that other sources of identity would have led the party to exclude. The legitimacy of the October Revolution rested most firmly on the myth of historical inevitability.

The great festivals and spectacles of 1920 helped create a foundation myth of the Revolution. Festivals can attack the center—the sacra of religion or the monuments of the state—but they can also raise new monuments and create new identities. They arrange time and space around moments of origin and embody its principles in the flesh and blood of myth. A nascent mythology of the October Revolution was discernible in Lenin's monument plan, in the dramatic games of the Red Army Studio, in holiday speeches and presentations, but they were

all lacking. The flaw was less in the content of the myths than in their form; they were diffuse and inclusive. Myth is compact and concentrated; it is embodied by individual people, in single places, and in concrete times.

In 1920, directors finally conquered the mass-spectacle form. They faced issues similar to those confronting the Bolsheviks: how to harmonize mass participation with efficient administration; how to include many origin tales without unraveling the thread of narrative. The solution was a strengthening of organizational hierarchy and a reduction of the chaos of revolutionary events to a compact narrative focused on a single time and place. Just as the Bolsheviks sacrificed old principles in the interests of a new identity, directors sacrificed historical veracity in the interests of myth. The results were striking. The mass spectacles of 1920 were dynamic, gripping, moving; through them, the Bolsheviks claimed an inalienable right to direct the fate of their country and the worldwide proletariat.

The Third International

If ever an organization was created by its own pomp and circumstance, it was the Third International. Barely fifty people attended its First Congress in Moscow in March 1919. Of those fifty, only twelve held credentials from any political group; of those twelve, eight were Russian Bolsheviks. Yet the Third International claimed to embody the aspirations of the world proletariat.

Perhaps it was fitting that some of the organization's funds were raised in subbotniki; the symbolic work of the holiday financed a symbolic proletariat.[5] The International, and the Russians who constituted the bulk of its Executive Committee, were in 1919 acutely aware of how tenuous their claim to world leadership was; so they complemented their political efforts with a series of symbolic gestures that laid claim to the center. The Red Army Studio's Third International was just one example. Most of the gestures were directed toward claiming the retired mantle of the First International; Marx's famous slogan, "Workers of the World Unite," was adopted as a motto. In the next five years the symbolic merging of the Russian state and the international revolution, exemplified by a 1921 poster linking the Paris Commune and the Russian Soviets (Figure 14), would receive prominent attention. In 1924,

Figure 14.

The Bolsheviks claimed the heritage of the Paris Commune,

as illustrated by this poster, captioned "The martyrs of the Paris Commune

were resurrected under the red banner of the Soviets" (1921).

Zinoviev presided over a ritual in which a "holy relic" of the Paris Commune, one of the last banners to fly over its barricades, was presented by French Communists to the Russians and laid on Lenin's tomb.[6] But in 1919 claims were more modest. Moscow was meant to be only a temporary headquarters; a permanent nerve center would be established in Berlin once communist revolution had swept Germany.[7]

The year between the First Congress and the Second in July 1920 brought an unpleasant surprise: world revolution did not break out. Moscow became the permanent center of world revolution by default. The Executive Committee of the International, mandated to direct operations between congresses, was an essentially Russian body, and its control of the movement solidified. The publication of Lenin's polemic "Left-Wing" Communism: An Infantile Disorder was a first attempt to impose Russian standards on foreign parties; and the Twenty-One Conditions for admission to the International, promulgated at the close of the Second Congress, established Moscow as model and center.

The magnificent complex of church and palace that is known as the Moscow Kremlin was given its present shape in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries under the first great Muscovite rulers, Ivan III and Ivan IV (the Terrible). Set atop a hill in the middle of the city, surrounded by massive walls, it is an architectural apotheosis of the medieval Russian autocracy: the center as source of power (state) and ideology (church). The creation of the Kremlin and its symbolic aspect coincided with the birth of the most powerful myth of Russian autocracy: Moscow as the Third Rome. The Russian state claimed through its church the mantle of the early Christians, forfeited first by Rome when it strayed from Orthodoxy and then by Constantinople when it was captured by the infidel Turks.[8] The Second Congress of the Third International, held in 1920, when the Soviets claimed the leadership of the world proletariat, convened in the Kremlin. As one of the delegates commented without irony:

Its architecture is supposed to symbolise a temple of honour of the sacred dignity of imperial power. A series of gilded columns run down the hall, but these were now swathed with red bunting in honour of the new power. Where once stood the throne now stood the platform for the presidium of the Congress. Over the throne, under the sweep of an arch, the "All-Seeing Eye" looked down. Long rows of desks stretched across the hall and red carpet covered the parquet floor.[9]

For the first time since the Revolution, the imperial eagles atop the Kremlin towers were regilded.[10]

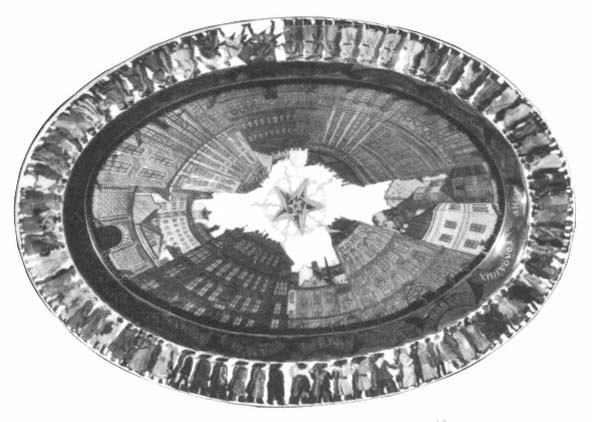

Literature and posters issued for the congress emphasized the theme of Moscow as center. The cover of the publication of the First Congress had depicted a worker beating the chains off a globe;[11] but a poster of the next year, Dmitry Moor's "Long Live the Third International," showed the same worker hailing the Kremlin (see Figure 15). A commemorative plate by Maria Lebedeva pictured the world movement as a series of concentric circles: on the outer ring, the world proletariat; next, the first stanza of the Internationale ; then the city; and, in the inner circle, a red star radiating the bolt of life from the heavens like Jehovah in the Sistine Chapel (see Figure 16).[12] Vladimir Narbut published a poem for the occasion:

Mongols, Negroes, and Arabs,

And you too, West of fiery aspect,

Use the wisdom of Socrates to create

The unhewn features

Of a Proletariat Atlas.

And may he, tremendous, made-of-steel,

Tense his muscles, as before

And take the Heavens on his shoulders,

Feet planted in Moscow and Resht.[13]

The Congress was first transported to Petrograd for a ceremonial opening in the Tauride Palace (built for Potemkin by Catherine II on her return from the Crimean tour). The Russians used that city's ceremonial center to receive their guests. The British and Italian delegations, who showed signs of cooperating with Bolshevik designs, were fíted with magnificent demonstrations by the army and trade unions through Palace Square; Zinoviev addressed the gathered multitudes from the same balcony once used by the tsar to address his people. (The French, who were intransigent, were given no such greeting.)[14] On the Field of Mars a Red Mass was performed, a requiem at the memorial grave of the "victims of the Revolution"; a brass orchestra and choir performed Wagner's Götterdämmerung .[15]

The foreign delegates could not have failed to notice the political irregularity of some of the symbolic gestures. Two monuments were erected in Petrograd: the one devoted to the Paris Commune was appropriate for a group that claimed the mantle of Marx; but the monument to Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, who one year before had objected strenuously to the founding of the Third International, was not.[16] Nor is it clear whether the visitors appreciated the Trial of the Yellow [Second] International , an agit-trial produced for the benefit of

Figure 15.

Graphic representations of the Third International, 1919 and 1920

(Mikhail German, ed., Serdtsem slushaia revoliutsiiu. Iskusstvo pervykh let oktiabria , Leningrad, 1980).

Photo (right) courtesy of Aurora Publishers.

Figure 16.

Maria Lebedevo's commemorative plate for the second Congress

of the Third International. Photo courtesy Aurora Publishers.

delegates who had yet to break with that organization.[17] But most outrageous was surely the fact that the Internationale, Pierre Degeyter's hymn of the workers' movement, was sung to new music; a competition for its composition had been held to which no foreign composer was invited. The jury was headed by Glazunov, ex-director of the Imperial Conservatory of Music.[18]

Any censure was quieted, though, by the magnificent spectacle Toward a World Commune, presented at the Stock Exchange from 10 p.m. to 4 a.m. on July 19.[19] Modeled on The Mystery of Liberated Labor, this production by four thousand soldiers and theater-circle members enacted the history of the Third International for foreign delegates and the citizens of Petrograd. Presented in the form of a mystery play, it portrayed history as cyclical; and the Russian Revolution, the dramatic climax of the performance, took on an inevitability it might not otherwise have had. The fact that the directors were given only ten days to prepare the performance could explain why they relied on tried-and-true methods.

Andreeva once again was the organizer of the event. She delegated directorial duties to Mardzhanov, just returned from Kiev (where, after his success with Fuente ovejuna, he had planned a mass spectacle entitled King Saul ).[20] Mardzhanov further delegated authority for separate episodes to young assistant directors. Petrov, of BDT and the Crooked Mirror, was assigned the first act; Radlov, the second; and Soloviev and Piotrovsky were given the third. For himself, Mardzhanov reserved the coordinating duties of the main director.

The preliminary scenario projected three acts: mankind's past—his enslavement; the present—struggle and victory; the future—the good life. The Third International was shown to be a by-product of European revolution.[21] Yet if the Russians were to be at its helm, they would have to claim its historical source. At Andreeva's instigation the play was changed to reflect the centrality of the Russian Revolution to the international, and to show that the Third International was the rightful heir of the First. The myth of the International was thus rewritten, and the Russians were at its center.

ACT I

Scene i. Communist Manifesto .

The rulers of the world, kings and bankers, erect a monument to their own power with the hands of the workers. . . . On top, a sumptuous celebration of the bourgeoisie; below, the workers' involuntary labor.

The laboring masses bring forward . . . the founders of the First international. The Communist Manifesto.

Only a small group of French workers answers the call to battle. They fling themselves into an attack on the stronghold of capitalism. The forward ranks, met by shots, fall. The red banner of the commune flies. The bourgeoisie flees. The workers seize its throne and destroy the monument to bourgeois power. The Paris Commune.

Scene ii. The Paris Commune and the Death of the First International .

A merry holiday for the Communards. Workers dance . . . the carmagnole. The Paris Commune decrees the foundations of a socialist order. New danger. The bourgeoisie . . . sends the legions of Prussia and Versailles against the First Proletarian Commune. The Communards build barricades, defend themselves bravely, and perish in unequal battle, without having received help from the workers of other nations. . . . The victors shoot the Communards. Workers remove the bodies of their fallen comrades and hide the trampled red banner for future battles. . . .

ACT II

The Second International

The reaction. The triumphal celebration of the victorious bourgeoisie. Below, the involuntary labor of workers reigns. Above, the leaders of the Second International, . . . noses buried in books and newspapers.

Call to war in 1914. The bourgeoisie shouts: "Hurrah for the war. Death to the enemy." The working masses murmur: "We don't want blood." . . . Again the red banner flies. Workers pass the banner from hand to hand and want to present it to the leaders of the Second International.

"You are our leaders. Lead us," shout the masses. The pseudoleaders scatter in confusion. Gendarmes . . . exult and tear apart the hated red banner. The horror and moans of workers.

The graveyard silence is broken by the prophetic words of the people's leader: "As that banner has been rent asunder, so shall the bodies of workers and peasants be torn by war. Down with war!" A traitorous shot strikes the tribune. Triumphant imperialists suggest a vote for war credits. The leaders of the Second International raise their hands after a moment's hesitation, grab their national flags, and split the previously unified mass of the world proletariat. Gerdarmes lead workers away in different directions. The shameful end of the Second International and the beginning of fratricidal world war.

ACT III

The Russian Commune

Scene i. World War .

The first battle. . . . The tsarist government herds long rows of bleak greatcoats to war. Wailing women try to hold the departing soldiers back. Workers, exhausted by starvation and excessive labor, join the women's protest. The wounded are brought back from the front. . . .

The workers' patience is through. Revolution begins. Automobiles, bristling with bayonets, charge by with red banners. The crowd, swept by revolutionary wrath, topples the tsar, then stops dead in amazement. Before the crowd are the new lords: the ministers of the Provisional Government of appeasers. They call for a continuation of the war "to a victorious conclusion" and send the workers into attack. A new courageous blow by the workers returning from the front, supported by a stream of unleashed workers, sweeps away the . . . government. Over the victorious proletariat flares the red banner of the Second Commune with the emblems of the Russian Socialist Federated Soviet Republic. . . .

Scene ii. Defense of the Soviet Republic—the Russian Commune .

Workers and soldiers, having shed their weapons, want to begin building a new life. But the bourgeoisie does not want to accept the loss of its supremacy and begins an embittered fight with the proletariat. The counterrevolution has temporary successes, . . . and only the greatest surge of heroism by the workers' Red Guard saves the Commune. Foreign imperialists send the Russian White Guard and mercenaries. . . . The danger increases. To the leaders' summons "To arms!" workers reply with the creation of the Red Army. Fugitives from areas razed by the Civil War appear. After them come workers from the smashed Hungarian Soviet Republic. The blood of the Hungarian workers calls for revenge. . . . The Red Army leads the heroic battle for the Hungarian and Russian workers, and for the workers of all the world.

Red labor befits the Red Army: it battles against the dislocations of war. The Communist subbotnik . Allegorical female figures of the proletarian victory issue a clarion summons to the workers of the world to the banner of the Third International for the final and decisive battle with world capitalism. The first lines of the workers' hymn.

APOTHEOSIS

The Third International. World Commune

A cannon volley heralds the breaking of the blockade of Soviet Russia and the victory of the world proletariat. The Red Army returns and is reviewed by the leaders of the Revolution in a ceremonial march. Kings' crowns are strewn at their feet. Festively decorated ships carrying the proletariat of the West go by. Workers of all the world, with emblems of labor, hurry to the holiday of the World Commune. In the sky flare greetings to the Congress in various languages: "Long live the Third International," "Workers of the world unite."

A general triumphal celebration to the hymn of the world Commune, the Internationale .[22]

As it had in Mystery, a holiday acted as the symbol of revolution and political ascendance in Toward a World Commune . The scenario as it stood differed little from the scenario of Mystery; the abstract scheme of oppression and revolution was the same, with the roles assigned to

more contemporary rebels. The apotheosis also differed little. As in previous mass spectacles, the Russian Revolution was the inevitable climax to the human drama.

The Craft of Mass Spectacles

Commune went beyond its predecessors, however, in production methods. Mardzhanov divided and delegated authority to his assistants; the cast was divided into smaller, more manageable groups, and the stage space was divided into sections, each with a distinct spatial value. (See Table 1 for a sample of the organizational chart used for the production.)

Marking the center was dependent on these new production skills. A center is a point alone, marked off from the rest of space and time; from it connections radiate out. It is created by both differentiation and unification. In Commune a myth of revolution was made by linking separate moments in historical progression. New production techniques enabled Mardzhanov to depict each moment distinctly and to shift rapidly between them. Mastery of the artifice of theater made the myth compelling and real.

Designs for the stage were done by Altman. Altman planned to do for the Stock Exchange what he had done for Palace Square in November 1918: subdivide the space by the use of color and shape. The outer three columns on each side of the portico were to be wrapped in red, and the middle six, uncovered, were to open up onto the central stage. The contrast between the two sets of columns would create an illusion of recessed space in the center. For this space Altman planned a dynamic composition, a "garden" of green triangles, before which was to be set a fiery red prism. At the back of the stage, on the second facade of the building there was to arise a huge golden sun, the "sun of October."[23] Altman redesigned the space of the Exchange for increased dynamism and flexibility. Andreeva, however, never forgot an old grudge, and she rejected the plan: green, she insisted, was the party color of the Constitutional Democrats.[24] Instead, the front cornice of the Exchange was hung with banners proclaiming "Long Live the Third International," appropriate more for a rally than for a spectacle.

Toward a World Commune was, more emphatically than Mystery, a theatrical spectacle. Curiously, when the theatrical, conventional use of a

property was most clearly underlined, that object could be used most easily in its "real" state. This was a paradox Radlov had discovered in The Blockade of Russia and that the directors of Mystery had failed to fathom. In that production, music was limited to providing an inexact thematic consonance: the rise of the proletariat was accompanied by the leitmotif of Wagner's Lohengrin and Rimsky-Korsakov's Sadko . Music in Commune was used as a real part of the everyday culture depicted: the privileged classes dance to Strauss's Vienna Waltz; the Paris Commune sings a carmagnole and buries its dead to Chopin's Funeral March . The stage was lit by the floodlights of a minesweeper moored on the Neva.[25] Battles were conducted by real soldiers and sailors firing from real guns and cannons (they fired real blanks, as had the Aurora on October 25, 1917) . The apotheosis was a parade of the victorious army, represented by troops of the Petrograd garrison, with armored cars and cavalry. Above the parade floated a dirigible trailing a banner that proclaimed, "The Kingdom of Workers Will Last Forever."[26] Of course, none of the fortyfive thousand spectators would have noticed the difference had actors and props replaced the real things, and, according to Radlov, the soldiers would scarcely have minded missing the march.[27] "Real," it seems, is a highly conventional notion. Spectators were alerted from the start that the spectacle was theater. They were summoned to the performance by heralds galloping down the city streets; but when they reached the Stock Exchange, they found a cordon of soldiers protecting the building and square (no protection had been provided for Mystery ).[28]

The differentiation of real and artificial, and the subdivision of the cast and acting space, offered the directors new opportunities and allowed them to gain control over an ungainly performance. In Mystery, the masses were led by a director placed in their midst. By the July 19 spectacle, the crowd of actors had become too big to control, and it was broken up into basic units: potentates, rebels, "yellow socialists." These units, defined by character and plot, were then subdivided into units of ten. Each united elected a leader; thus, a group of ten potentates would have a representative, who took commands from the chief of the potentate group. This numerical pyramid worked its way up to Mardzhanov at the tip. For rehearsals only the representatives were present; they in turn were to instruct the ten members of their cell and be responsible for their movements during the performance. With the moving crowd broken up into smaller units, the creation of patterns and rhythms was feasible. Crowd movements could be contrasted in geometrical patterns; individual movements like the lifting of a hand could trigger a contrasting mass

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(table continued on next page.)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

response, a charge. Sound, which had been drowned in Mystery, once again became an expressive component. Choral readings and singing were the main applications of the human voice; but voices could also be used in contrast, as when the thousand-throated groan greeting the declaration of the First World War was followed by a measure of silence, then a single voice: "As this banner is rent asunder. . . ."

To better control the massive spectacle, the directors removed themselves to a platform around one of the rostral columns that loomed across the square from the exchange. The platform was equipped with a bank of telephones and colored lights and flags that relayed signals to the minesweepers and Petro-Pavlovsk Fortress, and to the performers on the stage.[29] When the directors were distanced from the performers and the division between participant and spectator was explicit, there was little room for the creative participation of the masses. The performers, in fact, were mostly army conscripts, tired and hungry like the rest of Russia, and "mobilized by force."[30] Yet the changes did make for clearer expression.

The production's power was in the articulation of time and space. As in Mystery, the tripartite stage was used, but this time its conventions only abetted the sponsors' intentions. The Bolsheviks saw the history of the three Internationals as a cycle, with the Russian Revolution its rightful culmination. But this convention did not prevent the artistic categories of time and space from being subdivided. The stage wings were not removed from the action, and opposing sides did not necessarily mirror each other. The bourgeoisie could attack from the right, the workers from the left. Actors did not operate as a mass; they were divided into sections, static choruses, and moving groups.

Stage space was easily broken up and given definite identity. It could come, for instance, from the group occupying that space or from a simple emblem: when the tsar was toppled, the double-headed eagle fell and a banner proclaiming the soviets was raised. In the third section of the scenario the Allied blockade was depicted. At this point battleships on the Neva laid down a thick blanket of fog that enveloped all but the exchange and audience. The square, enclosed by these temporary walls, operated as a theater and was assigned a new value as conventional space. It represented the blockaded, isolated Russian republic. On the river beyond the fog the battleships, representing the Allies, blew their foghorns and fired cannons. The lighting of the huge flames of the rostral columns broke the fog and signaled the lifting of the blockade. The fog defining the theatrical enclosure melted away, and armored

trucks came driving through real space, across the bridge from the Petrograd side, to repel the enemy.

Staging historical material was a matter of selecting the proper episodes and assembling them into an artistic whole. In Commune, the basic incidents of the play were divided into 170 episodes, each defined by an exit or entrance.[31] Such a fine division was made possibly only by the system of cueing and signaling and the separate directorial platform. The Spartacus rebellion and the October Revolution had differed mainly in the uniforms worn by their participants in Mystery . Adding episodes to Commune allowed for more details so that successive revolutions looked less and less like each other. Historical progress could be detected.

Problems remained. The additional episodes required speedier transitions than could be made, and Commune was plagued by dead time—it was six hours long! The episodes also made the spectacle more complex; it is doubtful that most of the forty-five thousand spectators understood what it was about. The hundred or so delegates of the International, who were given pamphlets containing the plot in their native languages, could follow, and the performance, in any case, was directed at them, not at the spectators or the participants. To those people without a scenario in their hands, however, Toward a World Commune was "brightly colored, full of variety, majestic, but utterly incomprehensible."[32] Spectators probably saw little anyway; the directors' platform blocked part of the view, and a reviewing stand for foreign delegates was built up in the air, front-row center. Most of the Russians already had the suspicion the performance was not for them anyhow. It was initially scheduled for July 18, and the performers and spectators arrived hours early. At performance time all was ready, but the delegates of the International, still in conference, had not arrived. Rather than do the play without them, Andreeva dismissed the players and asked them to return the next day. Same time, same space.

Finding the Symbolic Center

At the advent of Bolshevik rule, there was a profound ambivalence toward Russia's symbolic centers. The ceremonial centers of Petrograd were inherited from previous regimes and had to be symbolically reoriented, which had been one objective of Lenin's unsuccess-

ful monument plan. Parade routes were another instrument of reorientation. Parades can be linear, with each place and spectator along the route being addressed equally; or they can be centripetal, with a central point being served above others. American towns usually define the town center as a street; the linear Veterans' Day parade marches down Main Street. Russian cities have always defined the city center as a point, and their parades have been centered. Moscow of course offered an ideal central point, Red Square, which had the additional advantage of centralizing celebrations in front of the seat of government. Postrevolutionary Petrograd was a more difficult problem. There were many potential central points: Palace Square, which would have been appropriate but for associations with the old regime and Provisional Government; the Field of Mars, centrally located yet a "neutral" site associated with both revolutions; and Smolny, the source of the Revolution and seat of the party yet located at the edge of town. May Day 1918 was focused on the Field of Mars (as had been May Day 1917); November 7, 1918, was celebrated at Smolny. And for the 1919 anniversary celebration, Uprising Square (formerly Znamenskaia), "where the first revolution began," was chosen.[33]

Parades also signal centers of power by whether they are made to see or to be seen: the first makes the marcher the center, the second the viewer—usually the VIPs on the tribune. On May Day, the marchers were taken all around Petrograd to see the fine decorations put up by artists and to let the marchers be seen by the city.[34] Afterward all gathered on the Field of Mars for some speeches, but this part of the festival was secondary, almost impromptu.[35] The Winter Palace was also deliberately assigned a "democratic" value; it was renamed the Palace of the Arts and was opened to the general public for the first time. Lines were tremendous, and the gesture was the most successful of an otherwise equivocal holiday. On November 7, a centralizing tendency absent on May Day was noticeable. A hierarchy of places and symbols developed, and with this a new centeredness, a hierarchy of participants. All parade routes led to Smolny; maneuvering the marchers past a single point led to the long periods of standing and to the human traffic jams that became a lamentable tradition.[36] Perhaps the most critical innovation was the tribune; leaders were segregated from the people and marked as the primary spectators.[37] The marchers filed through a seventy-five-foot temporary arch decorated with the new Soviet seal and past a smoke-currtained altar. Around the arch were placed obelisks, on which rested

busts of Lenin, Trotsky, Zinoviev, Volodarsky, Uritsky, Lunacharsky, Kamenev, and Sverdlov, as well as Marx and other socialist heroes.[38]

Palace Square would have to wait until 1920 for its time. Like Red Square, Palace Square was ideally suited to project an image of strong central authority. Marking the center of the city, occupying and imposing on its most valuable space, Palace Square also offered an opportunity for the central review of a parade. Only those unfortunate associations interfered. If the festival wanted the square for its own purposes, the image of the square would have to be "cleaned up." Renaming it Uritsky Square, after the slain Chekist, was an important change; and Altman's November 1918 decorations had subverted its old values; but symbolic reorientation was most fully effected by the May Day 1920 subbotnik . In the early eighteenth century the square before the palace had been a tree-lined park for public use; but it was gradually transformed by the dynasty into a appendage of the palace, a process completed in 1990, when Nicholas II ordered it enclosed by a massive iron fence. The subbotnik reopened the space to public circulation and linked it to the surrounding city. Still, though it was suitable for a review of the demonstration for the Third International in July, the square was not yet the mythic Palace Square, "center of the Revolution." That honor belonged to Smolny, as it should.

Agit-Prop, the state propaganda agency, issued a decree for the third anniversary forbidding large expenditures,[39] which essentially removed the outskirts and peripheries from the festival. In Petrograd only the central places, Smolny, Palace Square, and the Field of Mars, plus the graves of fallen revolutionaries in Lesnaia were to be decorated.[40] In that same spirit of frugality, Mayakovsky did a series of Russian Telegraph Agency posters condemning sumptuous celebrations:

He celebrates [the anniversary] correctly

who forgets all sort of carnivals,

and

tirelessly

fixes the railroads.[41]

But the message never made it to the Petrograd Soviet and the Northern Army. With victory close at hand, they ordered a magnificent festival, one that—if all plans had been realized—would have restructured the center of Petrograd. Petrograd was a city of long, broad avenues and yawning spaces embodying the values of order and power.

Festivals have often had a hand in determining the growth of a city; ancient Olympia was built entirely to the specifications of a festival, and the modern Olympics usually change the face of their host city. In fact Lazar Kaganovich, leader of Moscow in the 1930s, justified tearing down the jumbled alleys and churches of the capital by saying, "My aesthetics demands that the demonstration processions from the six districts of Moscow should all pour into Red Square at the same time."[42] But in 1920 Petrograd was far from its former imperial splendor; as Osip Mandelstam noted in an image of both degeneration and regeneration, grass was sprouting through the pavement.[43] There would be no major construction in Petrograd for many years; and the festivals, by gestures such as the placement of monuments, could define the city only by reorienting extant symbols.

That is not to say there were no plans for the physical reworking of Petrograd, just no funds. The third anniversary of the Revolution led to the formulation of one of the first postrevolutionary plans for altering the face of Petrograd. A massive spectacle was envisioned as the centerpiece of the festival; and had it been produced, the performance would have required great changes in the city. The performance was to stretch from Semenov Place to the Admiralty—about a mile altogether. Because the space between was not completely open, planners decided to clear several buildings to open a view.[44] On Semenov Place a monument was to be erected (as a model) that would have fixed a new center for both Petrograd and the world revolution: Tatlin's Monument to the Third International.

Tatlin's monument was designed to remedy the obvious deficiencies of the Lenin Plan. His working group was assembled in 1918 to draft plans for a monument that could change with time,[45] which would overcome the basic contradiction noted by Shklovsky: "I'm always surprised . . . by the intention to erect monuments to the Russian Revolution. It seems the Revolution hasn't died yet. It's somehow strange to build a monument to something still alive and developing. . . . The attempt to create this revolutionary art leads to the creation of false works of art."[46]

The Monument to the Third International rested on the tradition begun by Altman's restructuring of Palace Square for the first-anniversary celebration. Tatlin's monument, however, was designed to be permanent. Using the materials and reflecting the dynamics of the new (as yet nonexistent) urban environment, it was to consist of three great glass chambers connected by a system of vertical axes and spirals.

These chambers are arranged vertically above one another, and surrounded by various harmonic structures. By means of special machinery they must be kept in perpetual motion, but at different rates of speed. The lowest chamber is cubiform, and turns on its axis once a year; it is to be used for legislative purposes; in the future, conferences of the International and the meetings of congresses and other bodies will be held in it. The chamber above this is pyramidal in shape, and makes one revolution a month; administrative and other executive bodies will hold their meetings there. Finally, the third and highest part of the building will be used chiefly for information and propaganda, that is, as a bureau of information, for newpapers, and also as the place from where brochures and manifestos will be issued. Telegraphs, radio-apparatus, and lanterns for cinematograph performances will be installed. . . .

The use of spirals for monumental architecture means an enrichment of the composition. Just as the triangle, as an image of general equilibrium, is the best expression of the Renaissance, so the spiral is the most effective symbol of the modern spirit of the age. The countering of gravitation by buttresses is the purest classical form of statics; the classical form of bourgeois society, aiming at possession of the land and soil, was the horizontal; the spiral, which, rising from the earth, detaches itself from all animal, earthly, and oppressing interests, forms the purest expression of humanity set free by the Revolution. . . .

Most of the elements of architecture hitherto in use possessed no practical importance, and remained unorganized. To-day the principle of organization must rule and penetrate all art.[47]

Monuments define the symbolic center of a city; but dynamic constructions—like Altman's—tend to negate symbols and move to the periphery. There was some ambivalence about where the monument should be placed: in Moscow or Petrograd; in the center of the city or in the factory zone on the outskirts.[48] The issue was decided in planning for the third anniversary, when the Petrograd Party Committee decided to build the monument in Petrograd.[49] The model was to be exhibited as the center of the festival, and the space cleared would afford a view of the new center once it was constructed. The model, however, was never exhibited on the square; and the buildings were never knocked down. Petrograd would have to content itself with the old center of town, a center symbolically redefined.

In 1920 the center of Moscow was set firmly in Red Square. Previously, there had been ambivalence. The first-anniversary celebration of November 1918 provoked some controversy as to what the center of revolutionary Moscow was: organizers proposed creating an artificial center, a "Red city," extending from Red Square to the Metropolitan Hotel. The March-Route Committee thought Red Square should be the center, but the Central Organizing Committee preferred Theater

Square. Furthermore, as one delegate noted; "Those who will appreciate the entire majesty of the holiday with their hearts live, after all, on the outskirts. Why should they march to the center to amuse the bourgeosie?"[50] On May Day 1919, the demonstration was routed to Red Square; and it was there that Lenin addressed the masses. Yet even Red Square was not a uniform space; the placement of Lenin's Mausoleum by the Kremlin wall in 1924 would connect it to the center of power, but in 1919 Lenin gave his address from Lobnoe Mesto, located on the opposite side of the square and associated with Razin—a subverter of power.

The International Congress of 1920 helped fix the point. The Russians centered the International in Russia, in Moscow, in the Kremlin; and a huge military demonstration through Red Square marking the conclusion of the Congress on July 29 emphasized the symbolic claim to the center. Judging by their memoirs, the delegates were susceptible to the symbolic assault. Trotsky, the organizer, pulled out all the stops to show off Soviet power. Mayakovsky wrote striking verses that caught the spirit of the demonstration and the rhythm of its march.

We sally forth

a revolutionary charge.

Above the ranks

the scarlet flag of fire.

Led by the million-headed

Third International.

We advance.

No beginning to the flood of our ranks.

No end to the Red Army Volgas.

A belt of red-armies

to the West

from the East,

encircling the Earth

from the poles.[51]

Trotsky, flanked by delegates atop a tribune, reviewed the demonstration from noon to 5 P.M. The tribune, set by the Kremlin wall for the first time, was a mark of the center, concentrating the symbolic and political center in one. Around it were arrayed trophies seized from the allied intervention forces: cannons and transport, tanks and "other useful inventions of the bourgeois mind."[52] Buildings surrounding the square were hung with slogans stenciled on linen; marchers greeted the delegates with gold-lettered placards that sparkled in the sunshine. Sausage-shaped

balloons, trailing red pennants and streamers, were anchored to the crosses of St. Basil's onion domes.

The real show was the people. All of Moscow was turned out to march in the parade, though citizens were not allowed onto the square as spectators.[53] Boy Scouts trooped by and saluted the tribune; Caucasian tribesmen in native dress rode by. Athletes clad only in swim trunks made a particular impression. According to the press this was a perfect example of the potential of festivals to "create the new Soviet man." Exhausted workers had only to pass through the square with the rhythmic columns and they were transformed from "decrepit old men into handsome youths."[54]

Perhaps, but the political message sent to the foreign delegates was surely of greater consequence. Karl Radek's claim that "the demonstration . . . meant more than all the theoretical discussions [of the Congress]" was probably close to the truth. It established the claim of the Russians to be the source of international socialism's strength. A foreign delegate was overheard observing that it was "absolutely clear [!] that nobody could force such a mass onto the streets," a comment Radek used to refute Karl Kautsky's claim that the Russian workers' initiative was not manifest in the Revolution. But it was the pounding rhythm of marching feet, the tremendous organization of the demonstration that transmitted its message. The delegates, some of whom had been in Soviet Russia now for months, had not been impressed, to say the least, by the organization they had encountered. The Bolsheviks arranged the festival as a special show of organization, five hours of demonstration to erase months of contrary observations. The event seems to have made the proper impression. When Trotsky turned to a French Syndicalist and asked, "With all this, won't counterrevolution be impossible in Moscow?" the French comrade only silently nodded his head.[55]

The Myth of the Revolution

The Bolshevik claim to the center was best staked by a myth of origin: a myth that distilled the Revolution to a single moment. It was the instant of transition: the moment when history began and from which the future unfolded. Marx and ideology were irrelevant to this center of revolutionary history: it was the storming of the Winter

Palace that became the central theme of the Petrograd celebration after the plans for Semenov Place were jettisoned.

How was it possible to propagate a myth in the very city that had witnessed the event itself only three years before? Myths, contrary to what some symbolists and the "God-builders" thought, are not constructed at will. They are a function of memory: the more remote the memory, the more extreme the mythologization. Perhaps the Revolution was not very old, but already the recollection was slipping away from the facts and surrendering to art. Symbolically, John Reed, who left a distinct record of the events of October 25, 1917, died on October 24, 1920; and Podvoisky (one of the commanders of the palace storming), who was always consulted for productions of this kind, would later admit that he "could not remember how [he] crossed the barricades" (he hadn't!).[56] The Red Guardsmen remembered even less. Not that anyone forgot altogether; their recollections were if anything more vivid. It was just that some parts of the event were gradually neglected and forgotten, some were magnified, and the whole was rearranged.

History itself provided an outstanding example of such revision: the storming of the Bastille, which 130 years before had been made the center of the French Revolution by the popular imagination. The directness of the influence, and the inspiration it provided the Bolsheviks, was evident in a poster released for the anniversary:

Three years ago, comrades—do you remember? . . .

The Winter Palace fell—capitalism's Bastille.

And now Soviet Russia has become the center

Of the whole Laboring world—and with us

The peasants and workers of all countries are raising

The Red Banner of the Proletariat Revolution.[57]

A festival is not a neutral or "transparent" system; it is an artistic system in and of itself, with its own rules of aesthetic construction that it imposes on the material at hand. In this process remembered events are changed. Such a reformation of recollection was publicly enacted in The Storming of the Winter Palace, a mass spectacle presented for the third anniversary celebration of November 7, 1920.[58] The directors created a dynamic center for the Revolution, the moment of creation essential to any foundation myth.

The performance was sponsored by PUR. Tiomkin was again chosen to produce the festival, and he in turn chose Evreinov as director—an

odd choice indeed for the epitome of political theater: a director at best indifferent to the new ideology, who with his producer and designer would soon end up in the Paris emigration. For Evreinov the Revolution served the purposes of the performance, not the performance the Revolution. The facts were given an explicitly artistic organization. The Storming of the Winter Palace was a step beyond his "theatricalization of life"; it was a theatricalization of history, history as it should have been: "Historical events, serving as material for the creation of this play, are reduced here to a series of artistically simplified moments and situations. The directors did not consider reproducing exactly a picture of the events that took place three years ago on Palace Square; they could not because theater was never meant to serve as history's stenographer."[59]

But the storming of the Winter Palace, of all events commemorated by mass spectacles, was historically the most concrete. It was a localized event, one that had occurred at the same spot on which it was reenacted. Palace Square was at the same time a stage and a real historical place (see Figure 17). The directors went to great lengths to make the performance seem actual: trucks bristling with bayonets roared across the square, machine guns chattered, and out on the river the cruiser Aurora, which three years before had fired the (blank) "shot heard round the world," repeated the signal for the performance. Evreinov enlisted participants of the 1917 takeover as performers. The production staff even rebuilt the wooden barricade that had protected the palace's front gates and manned it with the Women's Death Battalion, which legend claimed defended the gates to the end. The highly theatrical gesture was not dimmed by the fact that the Death Battalion had, in 1917, wisely abandoned its position. Obviously, a distinction must be made, one that in a theater such as Stanislavsky's never received recognition: the distinction between "real"-ness and authenticity.

The mass performance would distill and improve the historical event. According to the directors, participants and spectators would in the course of an hour experience what in 1917 had been experienced in the course of many hours[60] —or, more accurately, it might be said, had never been experienced at all. The event of 1917 had, after all, been something of an anticlimax, occurring a day after the seizure of power. More important to the transfer of power had been attaining a majority in the Petrograd Soviet and the slow process of propagandizing the Petrograd garrison. On the actual day of the Revolution, Palace Square was one of the few peaceful points in the city: the Bolsheviks rightly thought the train stations and post offices of more import, and that was

Figure 17.

Layout of Palace Square, Petrograd, for the November 1920 mass spectacle;

image computer-enhanced (Istoriia sovetskogo teatra, Leningrad, 1933).

where conflict, what little there was, occurred. Winter Palace was surrounded, and Lenin desparately wanted it taken, but the commanders were in less of a rush. Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko, Podvoisky, and Grigory Chudnovsky, directors of the operation (in the production the trio was replaced by the single figure of Lenin), preferred to avoid senseless bloodshed and waited for a surrender. The troops defending the palace surrendered unit by unit over the next day, until finally the numerically superior Red Guard charged the building with scarcely a shot being fired. The eight thousand participants in the 1920 spectacle far outnumbered the attackers of 1917.

Although one hundred fifty thousand spectators were expected that night for the performance, because of dampness, chill rain, and slush, only one hundred thousand showed up—around one-quarter of the entire city. The spectators were well prepared; newspapers warned that the events would all be theatrical and requested that the audience not panic at the gunfire. There would be no reason to move during the performance; the stages were placed so that everyone could see.[61]

Spectators were placed right in the middle of the action (as they had been in Evreinov's Ancient Theater). Built against the facade of the General Staff Headquarters across the square from the palace was a huge stage designed by Annenkov. On the left side he constructed a Red city; dynamic, vertical buildings of red, factories, a large square, and even a memorial obelisk. Action on the Red platform was directed by Petrov. To the right (naturally) was the White platform, directed by Kugel and Derzhavin. Evreinov remained in charge of the entire production. The White platform was a horizontal construction made up of smaller platforms, none of which represented a specific place. On its left side, ladies and gentlemen in evening clothes campaigned for the Liberty Loan—here, Evreinov parodied an earlier mass festival. To the right, ministers of the Provisional Government, wearing top hats and sitting behind a long table, listened to Kerensky give a hysterical speech. Between the two platforms was a gangway, an architectural duplicate of the Headquarters Arch behind it, along which the two worlds met and did battle. The directors were placed on a large platform encircling the Alexander Column, equipped with a complicated network of electric signals. Spectators were cordoned off in large squares on both sides of the column and between the palace and headquarters. A few lucky ones watched from windows of the palace and surrounding buildings.

The Storming of the Winter Palace was conducted with a masterful sense of theatrical timing. At the stroke of ten, Palace Square was

plunged into darkness. A cannon shot shattered the silence, and an orchestra of 500, placed under the arch and directed by Varlikh, struck up Henri Litolff's Robespierre overture, introducing the White (!) platform. One hundred and fifty searchlights mounted on the roofs of surrounding buildings were switched on at once, illuminating the Whites, who opened the action. The Marseillaise, orchestrated as a polonaise, was begun as the ladies and gentlemen of high society awaited Kerensky's arrival. The prime minister, whose appearance caused some stir among the crowd on stage, was parodied brilliantly by an actor dressed in his characteristic khakis. The Whites formed a chorus, with Kerensky in the role of the coryphaeus (the figure who initiates and leads the chorus's response).

Directors of previous mass spectacles had avoided using individual actors, preferring to use masses of bodies to represent mass movements. The directors of Winter Palace reasoned correctly that in a large square filled with human bodies it would not be the huge mass that stands out but the single figure, particularly when that figure is spotlighted.[62] The proposal of Annenkov and Kugel to have twenty actors moving in unison play Kerensky was turned down. The advantages were immediately apparent. Kerensky, like the rest of the Whites, was played in the style of the opera-bouffe and the circus. The actor caught his histrionic gestures perfectly as he mimed a speech. The response of the White chorus was performed in the same style: Kerensky was showered with roses and ovations (all this had occurred during his Moscow Liberty Bond tour). Bankers, pushing money bags across the stage, volunteered their services for the Liberty Loan. Bureaucrats, backs bent in humility, vowed fealty to the first minister. And officers in cocked hats, monocled and bedecked with medals, held posters proclaiming "War to a Victorious End!"

Previous mass spectacles suffered most from an inability to transfer action from one episode to the next. This difficulty was similar to that experienced by writers of the medieval annals. The "syntax" of events was a coordinate system: this happened, then that happened. The subordinate syntax of events that underlies historical understanding was not truly available to the directors of the first mass spectacles, just as it had not been available to the annalists. In Mystery, the scenario might have specified that action shift at a certain point from the failed Spartacus rebellion at the top of the steps to renewed popular unrest, led by Razin, at the base of the staircase. The spectators, however, would see it differently; several hundred people in togas would still be milling about at the top of the

steps, and viewers would have to wonder what Romans were doing in Razin's Russia. The directors, then, had to take time out to clear the stage of the previous scene, as if erasing a blackboard. As a result these early performances took from four to five hours to complete.

Winter Palace, uniquely, was produced simultaneously as a drama and a film.[63] The analogy to film provided a solution to the time problem, which reduced Evreinov's production to only one and a half hours. In film, scenes can shift instantaneously; the time wasted in the theater occurs while the movie camera is turned off. In Winter Palace, action was moved not by shifting its location, but by shifting spectators' attention. The 150 searchlights were the solution: after Kerensky had made his speech and held court, and the scene shifted to the Red stage, a director on the column platform simply flicked a switch, plunging Kerensky and retinue into darkness, and another switch, lighting the Reds.

Lighting for the first time allowed for the division of a mass spectacle into distinct episodes and sharp contrasts. The dramas would no longer operate on "uninterrupted, festival" time[64] but on the subdivided time of theater, which yields to the manipulations of a director. In ritual drama (medieval mysteries or early Soviet mass dramas) there is a unity of performance time—the time frame in which the performance is viewed. There are no breaks in performance, no time when the performance is "turned off" and the spectator leaves the performative frame. Depicted time, however, is not unified; sharp, unexplained breaks and shifts—for example, from Spartacus's Rome to Robespierre's Paris—are the rule. Modern theater works on another scheme: performance time is broken, while depicted action is more continuous. Winter Palace, which finally solved the technical problems of mass spectacles, was the first in which depicted time was unified. With action concentrated in a single place and time, the festival was able to establish the palace seizure as the center of the Revolution. No historical myth is complete without that center, the moment of absolute change.

Action on the Red stage was in a monumental style; performers wore no make-up.[65] Acting was done in "collectives": characters were groups, not individuals like Kerensky, a device that demonstrated the collective character of the Reds. A few hundred workers come onstage from the factories Annenkov built for his city. While about half the group stand forestage and hold statuesque poses, the other half rhythmically strike anvils with their hammers. More people flood onstage and gather round a large red flag. The ever-increasing crowd falls silent, as if straining to hear something. The Internationale becomes faintly audible; then

cries of "Lenin, Lenin!" echo from the audience until the word is caught up by the chorus. The Red stage has been changing throughout this scene. Beginning as a gray mass, the workers grow brighter as the searchlights illuminate them ever more intensely. As the masses, which have been pouring onstage chaotically, become increasingly more organized, they gather around the flag and take up the chant. When the Internationale breaks out at full volume to end the episode, the gray mass has completed its transformation into the Red Guard.

Now the Reds can attack the Whites, with their troops surging over the connecting arch; this mystery-play device, used in every mass spectacle from The Overthrow of the Autocracy on, had its place in Winter Palace . Many troops from the White side go over to the Reds; only the Junkers and the Women's Battalion remain to defend the government. Oblivious to the unrest, Kerensky continues his oration, but his ministers, whose bench has begun to rattle and sway to the rhythm of the Red chants, crash to the floor at the clap of the first Red volley. Kerensky nimbly escapes to a car (American flag waving) waiting before the stage and drives away. His ministers follow in another car.

Up to this point, the performance could have taken place on any large stage. Space was conventional, its value assigned by the decor. Time was conventional; the events of a few revolutionary months of 1917 were summarized in an hour's dramatic action. But when Kerensky stepped over the proscenium, he stepped into real space. For Kerzhentsev, Meyerhold, and the symbolist generation, theater would attain its ideal when the audience crossed the same line in the opposite direction. That was the theater as ritual. Evreinov, however, pursued the theatricalization of life, the theater as play; history was replayed according to the rules of art. Ironically, Winter Palace, the height of artifice, was the most real of all the mass spectacles. Previous spectacles could have been performed anywhere anytime and have been about anything. By substituting a different set of revolutions The Mystery of Liberated Labor could become Toward a World Commune; that scenario could be replayed at Krasnoe selo. Winter Palace could only be about the October Revolution, it could be played only on Palace Square, and only on November 7. This performance fixed the final, irreducible center of the revolution.

Kerensky and his ministers, having driven madly across the square between the two masses of spectators, are admitted to the palace. Meanwhile, action continues on the stage, where the Red Guard and White soldiers battle for control of the city; this segment is performed like a

wartime battle spectacle. Suddenly, the lights inside the palace spring on, and in the brightly illuminated windows silhouettes grapple for control of the palace. A different stage of the struggle is depicted in each window, and the battle unfolds as each is illuminated in progression. The Reds gradually take the upper hand in these duels, and the palace finally falls under their control. The Revolution is accomplished. The searchlights of the Aurora, which have backlit the palace in an aura, switch to a point above the palace, where a tremendous red banner is raised, and red lights flash on in the windows. The performance ends with a comic scene from the revolutionary apochrypha; Kerensky flees the palace dressed as a woman. A cannon salute from the Aurora and fireworks end the festival and herald the dawning of a new age.