Expanded Fame

Between 1909 and 1911 Corinth received several portrait commissions. Although these works are of uneven quality, they are a measure of the growth of his reputation, for in each case the commission originated outside Berlin. In 1909 he painted the portrait of Ludwig Edinger (B.-C. 398), then director of the Senckelberg Neurological Institute in Frankfurt. From Hamburg came commissions for the portraits of Albert Kaumann (B.-C. 431) and Henry Simms (B.-C. 432), both painted in 1910, and for the portrait of Frau Kaumann (B.-C. 485), which dates from 1911. The Hamburg commissions may have come about through the recommendation of Alfred Lichtwark, who was keenly interested in the history of portraiture in the Hanseatic city-state and had published a book on the subject in 1899, urging that the tradition be encouraged and continued.[70] Lichtwark also personally commissioned from Corinth a portrait of Eduard Meyer for the Hamburg Kunsthalle. Meyer was a professor of history at the University of Berlin and a native of Hamburg. For Corinth this

commission was particularly important since by 1910 the Hamburg museum owned twenty-nine paintings by Liebermann and one by Slevogt but none by Corinth himself. Correspondence about this commission shows the extent to which Lichtwark's own views influenced the painter.[71]

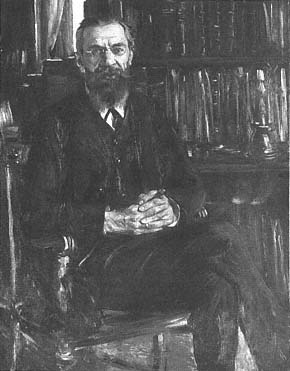

Lichtwark first approached Corinth about the Meyer portrait in November 1910. Since at the time Meyer was dean of the Philosophical Faculty at Berlin, Lichtwark suggested that the professor be depicted in academic dress standing by a large window in the dean's office, a suggestion that was not at all frivolous. Lichtwark clearly envisioned a portrait of some official character that would blend with other paintings already in the Kunsthalle collection, such as Liebermann's portrait of Mayor Carl Friedrich Petersen (1891) and Slevogt's portrait of Mayor William Henry O'Swald (1905), in both of which the sitters are depicted in their robes of office. As it turned out, Meyer rejected the idea as too pretentious and persuaded Corinth to paint him wearing an ordinary suit and in the privacy of his study (Fig. 112). Eduard Meyer (1855–1930) is seated nearly full-length before shelves filled with books, with what appears to be the corner of a window in an adjacent room at the upper left; the bright light entering from the right is reflected off the floor. Corinth made no effort to diminish the coarseness of Meyer's features, carefully emphasizing the facial characteristics, just as he attentively modeled the sitter's hands. Although the portrait ostensibly captures Meyer's habitual pose in casual conversation, there is a stiffness about the sitter that is reinforced by the restricted space and the well-ordered division of the background.

Corinth had completed the portrait by January 10, 1911, and a few weeks later sent it to Hamburg. Lichtwark was shocked when he first saw the painting and in a letter dated February 14 informed Corinth of his reaction. He was especially taken aback by the intensity of Meyer's gaze, and it seemed to him that the bright spot beneath the chair, in conjunction with the wall of books, virtually forced the sitter outside the picture frame. Although he acknowledged that he was gradually getting used to the portrait, he suggested that since Corinth now knew Eduard Meyer better, perhaps he could paint him a second time, but—as a pendant to the informal first portrait—wearing academic dress and standing by the large window in the dean's office, as first suggested. As an added inducement, it seems, Lichtwark in the same letter mentioned commissioning from Corinth a Hamburg landscape, a project that soon materialized (see Fig. 111).[72]

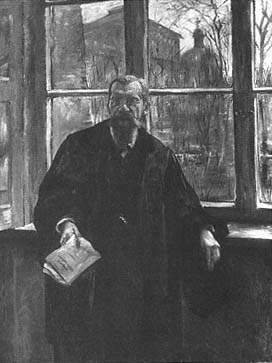

Meyer finally consented to Lichtwark's wish for a more "official" portrait, and Corinth began work on the second painting (Fig. 113) in late March. The

Figure 112

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Eduard Meyer , 1911. Oil

on canvas, 140 × 108 cm, B.-C. 498. Hamburger

Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1820).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

portrait follows Lichtwark's suggestions in virtually every respect. Meyer now wears a dark ultramarine academic robe; but his posture is relaxed, informal. Holding a velvet cap in one hand and a manuscript in the other, he leans on the windowsill in a moment of quiet concentration and reflection. The pages he holds add brightness to the lower left of the composition, balancing the bright expanse of the window.[73] Because window and wall no longer run parallel to the picture plane, as they do in the first portrait, the interior space seems more ample, and the large window extends the view out to a spring day enlivened only by a few specks of green and the pink of a bed of hyacinths. Knobelsdorff's elegant opera house on Unter den Linden and the cupola of St. Hedwig's Cathedral can be seen through the still-barren trees. Since the figure is illuminated from the back, Corinth was able to dispense with the details of individual forms, except for Meyer's head. With the summary treatment of the robe and the hands, however, the head acquires a spiritual strength that

Figure 113

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Eduard Meyer as Dean ,

1911. Oil on canvas, 198 × 150 cm, B.-C. 499.

Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg (1642).

Photo: Ralph Kleinhempel.

transfigures Meyer's countenance, lending him the dignity appropriate to his station in life.

Corinth considered the second Meyer portrait one of his best works, and Lichtwark was equally pleased. He not only followed through on the Hamburg landscape but also commissioned Corinth to paint yet another portrait for the museum's Hamburg gallery. The result was the huge portrait of Carl Hagenbeck (B.-C. 450), painted in October 1911. This portrait is not among Corinth's most successful works, largely because the big-game hunter and founder of the famous Hamburg zoo was forced to share top billing with one of his more spectacular charges, a fierce-looking walrus named Pallas. The painting is at best an interesting, though not entirely felicitous, contribution to the genre of the milieu portrait.

The Lichtwark commissions provide a rare glimpse into Corinth's financial transactions and reveal the prices he was able to obtain for his work at this

Figure 114

Lovis Corinth, Portrait of Frau Luther , 1911. Oil on canvas, 115.5 × 86.0 cm, B.-C. IX.

Niedersächsisches Landesmuseum, Landesgalerie, Hannover (KM 137/1949).

time. The Hamburg Kunsthalle acquired the second Meyer portrait and the view of the Köhlbrand for 2,500 marks each and the Hagenbeck portrait for 4,000 marks—low prices Corinth apparently agreed to only because he was eager to see his work in a major museum. When they were exhibited at the Berlin Secession in 1912, the view of the Köhlbrand was insured for 10,000 marks and the Hagenbeck portrait for 20,000. Corinth informed Lichtwark at the time that he would gladly work for the Kunsthalle again, but only for substantially higher prices.[74]

Another impressive portrait from 1911, of Frau Luther (Fig. 114), the wife of Hermann Luther, a wealthy sugar importer of Magdeburg, demonstrates again how much the quality of Corinth's portraits depends on his psychological response to the sitter. As in the portrait of Eduard von Keyserling from 1900 (see Plate 13), similar to this one in form and conception, the figure is seen against a neutral ground, and Corinth relied on blue to unify the composition, although here the colors are more vivid. Clearly Corinth was fascinated by Frau Luther's elegant demeanor. Yet her stylish appearance in no way interferes with her psychological presence. On the contrary, the face is modeled and characterized carefully, even unsparingly, with special emphasis on the puffy skin around the eyes. The enlarged veins accentuate the sensitivity of the well-groomed hands. Frau Luther may wear her striking dress and hat with nonchalance and gaze at the viewer with the self-assurance of her class, but her proud bearing and splendid wardrobe only serve to highlight her frailty and the onset of physical decay.

Corinth's output during 1911 was prodigious. He completed at least sixty-three paintings and made sixty prints, including twenty-six color lithograph illustrations for the Song of Songs (Schw. L82) published by Paul Cassirer's Pan Presse. His paintings by now numbered more than five hundred works, and Georg Biermann was ready to begin work on the first monograph on the artist. But on December 11 of this year, his most productive thus far, Corinth was felled by a stroke.