The Bath

Returning to the flagstone path, we notice the southwestern corner of the Xenon to our right; south of it and along the edge of a gravel surface of the ancient road runs a section of the terracotta aqueduct which brought water to the Bath. This simple aqueduct was constructed of U-shaped tiles, curvilinear inside, rectilinear outside. Covering the channel

[61] See Pausanias 2.15.3 for his description of the Heroön at Nemea; 1.42.8 for Ino-Leukothea; 5.13-1 for Pelops. Further comparison of these sites is invited by similarities in myth. Ino-Leukothea is identified as the mother of Melikertes-Palaimon, the hero of the Isthmian Games. The other two sites are also chthonic sanctuaries, i.e., the sanctuary of Chthonia at Hermione (2.35) and the sanctuary of the Mistress near Akakesion (8.37).

[62] See A. Mallwitz, Olympia und seine Bauten (Munich 1972) 133-38.

formed by these tiles were ordinary roof tiles, most frequently (as here) rectilinear, peaked Corinthian cover tiles (Fig. 37) but occasionally curvilinear Lakonian cover tiles or even flat pan tiles, apparently used in making repairs. East of the Basilica and beyond the modem cemetery, in the middle distance, is a ravine the floor of which has been leveled by modem agricultural activities. To the right (south) of this is a large modern reservoir and immediately beside it a Turkish fountain house (Fig. 37, at arrow). At one time these were fed, like the aqueduct for the Bath in its time, by a copious spring near the head of the ravine. That spring was tapped by a tunnel with a vaulted ceiling cut back some 16.40 m. into the bedrock (Fig. 38). Although its date has not been established, this tunnel would have been appropriate to the creation of the Bath.

From the flagstone path, with the Xenon to the east and the Bath to the west, we can see that the two structures are precisely the same width and have the same alignment. These similarities suggest that they were a part of the same building program, and excavations have shown that the aqueduct for the Bath is only slightly later than the Xenon.

Visitors enter the Bath by way of the large East Room (nearly 20 m. square) in the center of which are the foundations for four interior roof supports which form a smaller square (Fig. 39). The southeastern foundation retains its base (a large weathered gray block); the other foundations are preserved only far below the level of the original floor. During the Early Christian period this area was dug down some 0.40 m. below the level of the original floor; for this reason no evidence for the location of ancient doors has survived.

The West Room of the building consists of another large space divided into three east-west aisles by two rows of columns. In the northern row four of the five original bases remain; the central one was destroyed when the Nemea River forced its way through the building in early modem times.

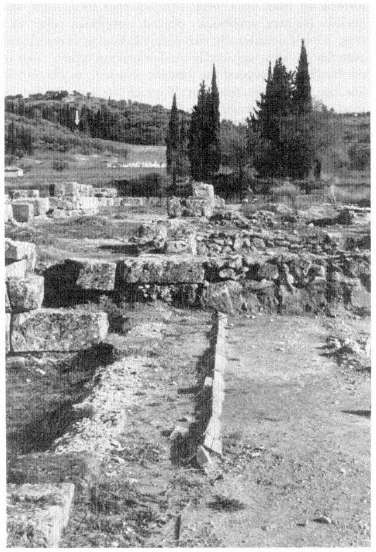

Fig. 37.

The aqueduct from the west, with Corinthian cover tiles in the foreground;

the arrow shows the region of the spring on the eastern side of the valley.

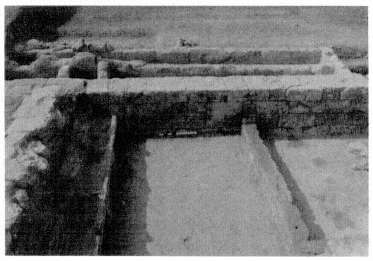

Fig. 38.

View of the rock-cut tunnel for the spring.

Fig. 39.

Restored plan of the Bath.

The rerouting of the river to its present course (very close to its ancient bed) took place only in 1924, after the Bath had been discovered.

The south aisle of the West Room is actually a sunken bathing chamber. The columns dividing it from the rest of the room (the bases of only the three furthest east are now visible) are actually projections from the line of the wall marking the limits of this bathing chamber. This chamber is approached from the middle aisle of the West Room through the intercolumniations to the right and left of the center column, beyond which a broad staircase leads downward. The Doric capital in the museum courtyard (A 7; see p. 73), discovered at the western end of this staircase, provides important details for the reconstruction of the interior colonnade. The intercolumniations flanking the two at the center were blocked by a parapet over the sunken chamber to prevent accidents; several blocks of that parapet have been reerected in something like their original positions.

The bathing chamber is itself divided into three parts, all of which exhibit heavy coats (in some areas two layers thick) of hydraulic cement. The wide Central Pool is separated from the smaller flanking rooms by a wall which was about chest high originally, as is indicated by a socket cut into the south wall (Fig. 40). The flanking rooms are virtual mirror images of one another. Each was entered by the side steps of the staircase, and each is equipped with four stone tubs placed end to end along its rear wall. These tubs were fed by a stone water channel set back into the wall; it was pierced at appropriate intervals by holes through which the water flowed into the individual tubs.

Although two tubs have V-shaped notches in their sides for overflow, none of the tubs is equipped with an outlet. Notches cut at the top of their common walls allowed water to flow from one tub to another. Wastewater in the East Tub Room flowed across the floor to an opening at the corner of the staircase. A terracotta channel under the staircase, behind its

Fig. 40.

View of the bathing chamber from the north.

first step, carried the water to the opposite corner of the staircase, where it simply flowed out over the floor of the West Tub Room to a hole beneath the northernmost tub. This, in turn, connected with the Nemea River. Wastewater from the West Tub Room itself flowed to the same hole, whereas that of the Central Pool ran into a hole at its own northwestern corner to join the channel beneath the staircase; from there it flowed through the same system as the wastewater of the East Tub Room. For the wastewater system to work, the floors of the rooms had to be progressively lower toward the west.[63]

A hole in the south, or back, wall of the Central Pool marks the entry point for its water; its height shows that the water in this pool would have been about chest high or slightly lower and that the pool itself was intended as a plunge bath. The tubs in the flanking rooms were too shallow and short to

[63] The hole at the base of the north wall of the West Tub Room and the cement channel set into the ancient floor leading to it are not ancient but were created in 1958 by N. Verdelis of the Archaeological Service.

Fig. 41.

Restored perspective of the bathing chamber.

be individual bathing tubs. Ancient representations show clearly that they were meant to be used as basins from which to splash or throw water on the body (Fig. 41).

Parts of the reservoir system that supplied water are visible from the southwestern corner of the East Room. These would have been fed by the aqueduct, but the remains at the point of connection have been obliterated. Nonetheless, the general workings are clear. Two long narrow reservoirs, originally about 1.00 m. deep and 0.60 m. wide, run alongside the exterior south wall of the building. The one closer to the building is interrupted just at the southeastern comer of the East Tub Room where a smaller tank, a 0.60 m. square "water closet," is formed. Both the larger and the smaller reservoirs served only the East Tub Room, and the existence of the water closet shows that the flow of water was not constant but rather was regulated by periodic flushings of the water closet.

The reservoir west of the water closet and the entire southern reservoir served the Central Pool and the West Tub Room. Whereas probably the pool was completely filled and emptied at intervals of several days, the West Tub Room would have been regulated in the same manner as the East Tub Room. Unfortunately the reservoirs west of the inlet to the Central Pool are not preserved, so that the details of operation are not certain.

The Bath, firmly dated to the last third of the 4th century B.C. , is one of the earliest bathing systems known in the Greek world. More difficult than dating, however, is the assignment of a precise ancient name. At an athletic center like Nemea we would expect a palaistra-gymnasion complex, and the palaistrai of Delphi and Olympia, to cite the most relevant examples, were equipped with bathing facilities.[64] They seem, however, to be a generation or so later than the example at Nemea. Moreover, the Nemea structure, although sizable, does not have all the subsidiary rooms (for boxing, oiling, etc.) we expect in a palaistra , nor does it have the practice running tracks, approximately 200 m. long, always found in a gymnasion . At Delphi and Olympia such tracks are obviously present, but at Nemea there is no space available for them in association with the Bath.

Without evidence for the ancient name,[65] it seems best to refer to the building as a bath and to leave open questions about the restriction of its use to athletes.[66]