Chapter Three—

Revolution and Oil

The Mexican Revolution abounded with rumors of conspiracies. How could it have been otherwise? The mercurial politics of revolution dictated that domestic politicians had to choose sides. The wrong choice often meant exclusion and exile, loss of property, or death. Foreign businessmen also felt pressure to be swept into the rumor mongering, to prevent a competitor from gaining advantage with the political regime of the moment. Often, the deeds of foreign businessmen did not substantiate the charges and rumors, as few actually felt they could really influence a revolution that appeared to them to be a strictly Mexican affair. Inasmuch as revolutionary factions were struggling over who would deal with foreign interests, the foreigners themselves had to deal with the truly byzantine power struggles.[1] Therefore, many Mexican power contenders easily believed in the machinations of the powerful, distant forces of Wall Street and The City. How else can the success of unworthy enemies be explained?

The problem for the foreigners was that they became coconspirators in the game of innuendo and unsubstantiated allegation. After all, the mere change of government signaled an enormous adjustment in the political involvement of foreign interests. Old power brokers became excluded from influence, while new aspirants took command of the perquisites of office. The changeover at the top invalidated the oilman's connections to the Científicos. Now maderistas, huertistas, convencionalistas, and carrancistas replaced each other in bewilderingly quick succession. The foreign businessmen themselves succumbed to the rumor

mongering. Hoping to gain some business advantage for themselves, either the foreign oilmen were quick to anticipate a competitor's political maneuver or they propagated rumors to prevent a rival's maneuver. In essence, the foreign business community was divided against itself, company against company, and Americans against the British.

The continuation of the Mexican Revolution more than inconvenienced the foreigners. The longer the struggle continued and the more actively the Mexican peasants and laborers became involved, the greater the economic destruction and the disruption of business-as-usual. While licenses for pipelines and refineries languished at the top, the oil companies became susceptible to paying double taxation, forced loans, and bribes to competing revolutionary factions. No capitalistic organization, least of all these penny-pinching oil competitors, desired to dole out that kind of money to every passing army general and bandit straggler. But the oil companies did just that. Moreover, the competition for military superiority made its way from the central plateau down into the hot-lands. The longer the revolutionary violence lasted — roughly from the Orozco rebellion against Diaz in January 1911 to the successful rebellion of General Obregón against President Carranza in May 1920 — the more inviting the oil industry became to the competing factions. It was the only sector of the economy that boomed during this period. Therefore, the oil industry was seen increasingly as a revenue source for penurious revolutionary governments and their political opponents.

Ultimately, the revolution enhanced economic nationalism in Mexico. Revolution created in the state a severe need for monies with which to reestablish control over the social furies unleashed by revolution. The state sought the essential revenues from the prosperous foreign interests. When those foreigners resisted, the politicians would accuse them of complicity in creating the conditions of revolution in the first place. All in all, control and ability to tax meant about the same thing to revolutionary politicians. Other Latin American countries, in time, would achieve economic nationalism without revolution. But always, a domestic environment of political and social stress underlay the creation of economic nationalism.[2] In Mexico, that stress became dramatically extreme.

Their inevitable political involvement in the Revolution itself — either through rumor of their own making or through coercion by contending factions — rendered the foreign companies susceptible to heightened exactions by successive governments and rival factions. No one was immune from the political struggle. Therefore, even as the in-

dustry itself grew according to the market dictates of the great Mexican oil boom, the revolutionary process and the oilmen's complicity in it were subjecting the industry to political intervention. The fact is, state control and regulation increased; Mexican politicians willed it; the Revolution sanctioned it; and the foreign oilmen, despite their accumulated wealth, were too divided to stop it. Economic nationalism in Mexico had a social base, and that is why the social revolution of 1910 to 1920 also produced an economic nationalism bent on reducing the power of the foreign oil companies.

The Smaller the Better

The rumors began to surface as soon as the initial rebellion of the Mexican Revolution succeeded in sending President Díaz into exile and placing the green, white, and red sash of executive office across the torso of Francisco I. Madero. Reports appeared in London newspapers that Waters-Pierce had financed the rebellion in order to obtain important oil concessions from the victorious Madero. Mexican newspapers recounted the rumors. Along the northern border, conversations among Americans and Mexicans turned to the conspiracy of Standard Oil to provide Madero with a one-million-dollar loan. Again, important oil concessions from the Madero regime were to be the pay-off. Nearly everyone recounted stories to each other of the support of Lord Cowdray for the Diaz regime and how Doheny and Standard Oil desired and worked for the overthrow of the Anglophile porfiristas.[3]

Perhaps historians will never be able to document who started which rumor, but little evidence exists that any company willingly gave money to any Mexican faction. Even the circumstantial evidence is very spurious. By the same token, there is no doubt that the oilmen themselves engaged in the rumor mongering because they half-believed the political malevolence of their rivals. As they had been involved in the politics of the Porfirian regime, so the oilmen became involved in the machinations of the Madero regime too. Perhaps a distinction should be made between involvement and intervention. To be involved in Mexican affairs, all the oilmen had to do was be present and be a source of income for Mexican politicians and revenues for the state. They had to depend to a degree on political support for obtaining licenses and economic privileges. Thus, the rumors were testimony to the involvement of the foreign oil companies in domestic Mexican

politics during the Revolution. To intervene in politics, however, the oilmen had to voluntarily direct their resources to influencing the outcome of disputes between Mexican politicians. Involvement was vastly more common among oilmen than intervention.

The rumor that the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey had financially supported the successful Madero rebellion would not die. As the story went, American oilmen resented the Diaz government for having supported the British oil interests of El Aguila. Everyone had heard some version of C. R. Troxel's alleged negotiations for Standard Oil (see chapter 1). Both Mexicans and Americans continued to repeat these rumors. They did so in newspapers and political proclamations and under oath in U.S. Senate hearings. Therefore, a Mexican attorney who once served some foreign oilmen could calmly testify to Standard Oil's financing of John Kenneth Turner's book Barbarous Mexico, which had vilified the Diaz regime for an otherwise adoring American public.[4] An American agriculturalist in Mexico claimed that "a brother of my cashier" had seen a check from the Madero government made out to Waters-Pierce. The check had overpaid for a government purchase of kerosene in order to repay Pierce for his loan to the Madero rebellion. When erstwhile ally Gen. Pascual Orozco broke with the Madero government and condemned Don Francisco for having accepted "FOURTEEN MILLION dollars from Wall Street millionaires," Orozco pointed to the Waters-Pierce Oil Company, which had hoped to widen its petroleum sales to the Mexican National Railways. A second rumor immediately arose: Lord Cowdray was financing the Orozco revolt because Madero had revoked El Aguila's Díaz-era concessions. In fact, the concessions had not been revoked.[5]

Lord Cowdray was convinced that Henry Clay Pierce was behind many of the malicious stories. When El Diario broke the news in 1912 that Standard Oil, "that great oil octopus," was about to purchase El Aguila, Cowdray suspected that the news items were the work of Pierce. "He employed Press men, unscrupulous but able, to attack us, day by day, in the American and Mexican Press," Cowdray wrote confidentially. "[Pierce] issued a pamphlet which was sold on the London bookstalls. He accused us of having bribed and corrupted the Díaz Government and of doing the same to each of the revolutionists that for the moment, were in disfavour. I was shadowed when in America."[6]

One who did know rather more about the connections — or lack thereof — between Madero and the foreign interests was Madero's American consultant. Shelburne Hopkins was a confidant of the Ma-

deros, acting as their counsel on retainer for American affairs. He had even been in a position to know a bit about Waters-Pierce. The company employed Hopkins in 1912 to "get evidence" against the Standard Oil Company in Mexico. Hopkins claimed that Madero had received no money at all, whether from Standard Oil or Waters-Pierce. Although the American oil importer wanted to "make it hot" for El Aguila, Waters-Pierce obtained no advantages at all from the Madero rebellion. Hopkins claimed that much of Pierce's animosity derived not from the oil business but from the Porfirian consolidation of the railways. As principal stockholder of the Central Railways, he had approved of Limantour's railroad stock purchases and consolidation of the Mexican National Railways. What Pierce distrusted was those Mexican notables — Creel, Landa y Escandón, Pablo Macedo, Luis Elguera, and even Porfirio Díaz, Jr. — who subsequently joined Limantour's new board of directors of the National Railways. They were all Pearson men. Therefore, Pierce approved of Madero's removal of these porfiristas from the directorate of the National Railways although, said Hopkins, Madero had not consulted Pierce about these replacements.[7] If Don Porfirio's economy had been politicized, so was Don Francisco's.

In 1913 and 1919, the United States convened public hearings into allegations of American interference in the affairs of Mexico, as well as to propose U.S. policy alternatives toward the Revolution. Senator Albert B. Fall had interviewed witnesses in El Paso and Los Angeles. He found that, although rumors abounded as to the American oil interests' financing of the Madero rebellion, "very few persons had any definite knowledge upon the subject." He concluded that the Maderos had supported themselves substantially from family funds. Other revolutionists "largely supported themselves by killing and rustling cattle and sheep, by looting stores, and by securing forced contributions." The American oil interests, therefore, "should be exculpated of the charge that they incited or promoted the revolution against the Díaz Government," Fall wrote in 1913.[8] Fall's judgment may be trusted. His closest ties to American oilmen were not to Standard Oil or Pierce. They were to Doheny and Harry Sinclair, neither of whom were involved in the controversy. Nevertheless, few Mexicans and Americans along the border paid much attention to the conclusions of Senate hearings. The rumors persisted and were believed.

While Madero was in power, from 1911 to 1913, the actual relations between the oil company representatives and the government continued to be formally correct. Foreigners still needed political insiders in

order to accomplish official business, as in the old regime. Only one oilman's archive, that of Lord Cowdray, is extant to provide a glimpse of the important art of business diplomacy. The Pearson interests had the most arduous task with the Maderos. They had to quietly shed the image of having been cozy with the discredited Porfirians. It was not easy. Nasty little reminders always cropped up in newspapers in Mexico and the United States, thanks, said Cowdray, to his rival Henry Clay Pierce. The Pearson group also sensed the urgency of a rapprochement with the Maderos when Manuel Calero, described as Doheny's representative in Mexico City, joined the government as minister of development. Fortunately, J. B. Body knew Ernesto Madero, the uncle of the incoming president. But Ernesto admitted hostility toward the Pearsons, accusing them of attempting to influence American policy in favor of Díaz during the revolt.[9]

Nonetheless, Francisco I. Madero and Lord Cowdray met in August 1911. Responding to Cowdray's primary concern, Madero said that he intended to respect all Díaz-era contracts and concessions. He also assured Cowdray that he had never had any ties to Standard Oil; all the money for the rebellion had been raised by Mexican donors. Madero's own father had raised $350,000, using his properties as collateral. Cowdray informed Madero that he believed Pierce to be behind the scurrilous press attacks. Cowdray said he had never meddled in Mexican politics. It appeared a frank meeting, based upon the notes of Body. Cowdray informed the future Mexican president that he needed funds to expand El Aguila's markets, perhaps combining with a larger oil company. Madero replied that he would "look with suspicion" on the sale of El Aguila to Standard Oil, and Cowdray quickly added that he was considering The Texas Company or Gulf.[10] Perhaps the Madero government would not be so bad for the Pearson oil interests, after all.

At any rate, the early political breakdown of the Madero regime did not permit the Pearson group to develop a lasting, profitable relationship. El Aguila's pipeline permits for Bustos-Tancochín were held up in the secretariat of development by the influence of the Doheny interests, Body thought. Rising political tension may have been more at fault. When the battle between Madero's federal army and Orozco broke out at Torreón, Body wrote that it was becoming "most difficult to transact any business in the Government Departments, and I fear we shall be at a stand still until things change."[11]

Still, Cowdray found himself working on behalf of the Madero government in March 1912. While in the United States, Cowdray spoke to

the brother of President William Howard Taft about the need to prevent the sale of arms across the border to Orozco's rebel forces. Eventually, the executives had to devise a code so that they could discuss the political turmoil in Mexico so that, if compromised, its correspondence "might [not] be viewed unfavourably by other parties."[12] Despite the cordial relations, the British managers were ever suspicious that the Americans might have more influence with Madero.

Body in Mexico City thought that the Doheny representatives had obtained major political advantages with the Madero government. Near panic derived from two Porfirians still on El Aguila's staff, Enrique Creel and attorney Riba. "We must prepare action to counteract," Body cabled to Cowdray. Cowdray agreed.[13] None of the documents reveal what issue concerned the Pearson group, whether pipeline rights-of-way or fuel oil sales. The crisis passed quickly — or at least was overwhelmed by Madero's mounting political problems. When he had to make a cabinet change in November 1912, Madero's foreign affairs secretary asked Lord Cowdray to wire a note of his "satisfaction" with the new appointees. The Pearson representatives were willing to comply, although privately they said they would have preferred it if the brief rebellion of Félix Díaz, nephew of Don Porfirio, had been successful.[14]

As the fortunes of the regime sank, the Maderos turned to the foreign interests for money. Ernesto Madero devised a scheme to buy the opposition newspapers in Mexico City and asked J. B. Body to contribute $ 100,000 toward this end. Cowdray was put out. He felt obliged to contribute something so that Madero would not consider a refusal to be an "unfriendly act." "[W]e ought to subscribe whether we like it or not," he wrote Body, "of course, the smaller the better."[15] The fall of Madero and his assassination within a month relieved the Pearsons of this obligation. Yet, they had succeeded in gaining a degree of cooperation from the Madero government despite the persistent rumors.

Rumors and Wise Precautions

Much of the animus that developed between the various revolutionary governments and the oil industry was a matter of both principles and finances. It was a fight between advocates of alien concepts of free enterprise and state control. Foreign oilmen subscribed to Adam Smith's ideas that the pursuit of private interest will contribute

to the general wealth. For example, Doheny never felt any embarrassment about how rich he had become on Mexican oil. He did not exploit anyone, he said. He paid "honest prices" for his land, and the Mexican landowners who leased to him were the envy of their neighbors. Doheny's attorneys, he said, were constantly decrying the high prices that he paid for his leases.[16] The revolutionary state, on the other hand, wished to control and direct national life in a way that would avoid the causes of revolutionary outbreaks. For the twentieth-century state to do this — as for the colonial royal government to have done it — revenues were required. In the colonial period, the silver mines provided the resources. In the twentieth century, the oil and other advanced industries provided those revenues. The difference was that the industry of early twentieth-century Mexico was owned by foreign capital.

The Madero regime, pressed for funds, began to look to the oil industry soon after coming to power. The Díaz-era budget surpluses dwindled — but did not yet disappear — as Madero attempted to satisfy old Porfirian families and new political players. The federal army and the rurales, for instance, augmented the numbers deliberately shrunk by Porfirio Diaz. Some old insurrectos like Emilio Madero, Pascual Orozco, and Pancho Villa were brothers in arms with Generals Reyes, Blanquet, and Huerta. The army payroll nearly doubled. Military expenditures mounted when the zapatistas continued their rebellion, and Orozco and others followed suit. How to raise money? Congressman José María Lozano introduced a bill to tax all oil lands, because their export of petroleum was contractually tax-free for fifty years. Lozano said he wanted to free Mexico from the clutches of Standard Oil, which was attempting to take over El Aguila. To Lozano, taxation was an instrument of control.[17] In Veracruz, the state legislature considered a proposal to impose a state tax of fourteen centavos per ton on crude oil. Both El Aguila and Huasteca sent their Mexican attorneys to confer with the state governor, who anyway was unwilling to press forward until President Madero and Minister of Development Calera approved. They did not. They were preparing their own federal tax increases. Meanwhile, the representatives of twenty oil companies organized a coordinated protest against the state deputies.[18] Oil company protests were often couched in predictions that any increased taxation would undercut economic growth and the country's tax base. "It is possible that this [tax increase] might cause the cancellation of otherwise profitable contracts and thus greatly reduce the amount which the Government desires to realize," Harold Walker of Huasteca warned.[19] In the

end, the oilmen settled for a compromise, getting the state government to reduce its tax demands. Yet, taxes did rise from their previous level.

What oilmen feared most was any break with an 1887 Mexican law which stated that petroleum was subject only to the stamp tax. But by this time, the break had already been made. The Porfirian regime had imposed bar taxes at Tampico, the proceeds of which ostensibly financed the dredging of the harbor. The oil companies agreed to pay the modest tax just to avoid higher taxes. The tax exemption of Huasteca as a pioneer company also expired in 1911. Thereafter, it could no longer import new equipment duty free.[20] Then, late in 1912, Madero proposed to increase the bar tax to thirty centavos per ton. Once again, the oilmen pooled their resources, protested in unison, sent their attorneys to speak with congressmen, and wrote pamphlets about how Mexican oil would be priced out of international markets. Again, the big companies effected a compromise, agreeing to pay one-third of the increased tax. Representatives of the smaller companies were disgusted. William Buckley later pointed to these Díaz- and Madero-era compromises as the beginning of "the troubles of the oil companies."[21] Ever cognizant of its need for government goodwill, El Aguila always seemed to be in the vanguard of compromise. Ernesto Madero later praised the company for not meddling in Mexican politics.[22] Yet Buckley was essentially correct. The Mexican state had begun imposing some new rules on the oil industry even as it began to boom. The process would intensify.

The Madero revolution and its political problems also began to erode the sense of security that the oil operations had enjoyed during the Díaz era. When Orozco revolted in March 1912, the "rumors" of impending trouble motivated the sometimes isolated oil managers to arm themselves. At the Minatitlán refinery, A. E. Chambers requested that he be permitted, as a "wise precaution," to import 20 rifles and organize a force of volunteers. Foreign diplomats soon entered into the action. The British minister at Mexico City acquired 160 rifles from the Mexican government for distribution to the British "defence committee" in the capital. It was reported also that the U.S. ambassador had 1,500 rifles imported for the protection of his countrymen.[23] In Tampico, the Waters-Pierce refinery obtained rifles and ammunition, as did El Aguila, which imported 90 carbines and 9,000 cartridges. The Americans working for J. A. Sharp of the Petroleum Iron Works Company, constructing tank farms at Topila, requested 20 guns and 400 cartridges. The arming of frightened foreign oilmen was done

with the consent of government authorities. The governor of Tamaulipas and the local military commander assisted in arming the foreign community at Tampico.[24] This arming of foreigners was a waste. No foreigners in the oil patches were any match for even the smallest military patrols. Various revolutionary factions would soon disarm the foreigners, who were also relieved of much else.

If foreign businessmen were inextricably involved in domestic politics, then their greatest need was for stability. Only in an atmosphere of political calm could the oilman establish the long-term relationships with insiders so essential to obtaining construction permits, oil concessions, tax exemptions, and domestic sales. The extent of state control of industry in the second decade of the twentieth century was just this modest. As yet, the Mexican state did not regulate drilling, production, oil exports, or domestic prices. It had not yet gained control of oil property. Therefore, the oil business proceeded in full boom, despite the political tribulations of the Mexican Revolution. Still, the political disruption did affect the oilmen. This was true for two reasons. During the revolution, fiscal deficits grew, motivating each succeeding government to seek new taxes on the booming oil companies. Also, competing politicians became increasingly inclined to blame the foreign interests for their own political problems — and for the nation's, as well.

Therefore, the fall of the Madero government, although first welcomed by foreigners already weary of political turmoil, proved to be the beginning of their considerable vexations in Mexico. When Madero fell from power, the oilmen scrambled to establish friendly relations with the new regime, whichever it was to be. J. B. Body of the Pearson group rushed immediately to see Gen. Félix Díaz, nephew of the former president. Body and Lord Cowdray were thinking that Díaz would be the next president. (Privately, they preferred Díaz to General Huerta.) Cautiously, Body refrained from making "real propaganda" with any faction, except to cultivate them all. Then news broke like a thunderclap that Madero and his vice-president, Pino Suárez, had been assassinated by their jailers. Body was horrified.[25]

Nevertheless, the new provisional government headed by Gen. Victoriano Huerta had to be cultivated. Body paid courtesy calls on all of the new ministers. The new cabinet already understood how the game worked. The minister of justice asked Body for information regarding Huasteca. Then the foreign minister requested that Lord Cowdray use his influence to obtain British recognition of the Huerta government. On both requests, Body said he would try. Body subsequently called

on the British ambassador, whom he convinced that British recognition of Huerta would be appropriate if only to counteract the American ambassador's enthusiasm for Huerta. Huerta even asked Lord Cowdray to use his influence with the British government to retain the British ambassador, Sir Francis Stronge, whom Huerta liked. Stronge was replaced anyway.[26] Other foreigners also interceded with their home governments for recognition of the Huerta government, but the Americans did not have any success with President Wilson.[27] Still, they discovered that this inexpensive aid was a way of ingratiating themselves with the new regime.

Men in and out of government continued to court favor with the oilmen, and vice versa. How could oilmen not do otherwise when today's outcast might well become tomorrow's minister? On learning of Félix Díaz's arrival in London, Lord Cowdray sent a motorcar for his use and invited his old friend's nephew to dinner. Meanwhile, the surviving Maderos were also treated with respect. From his exile in San Sebastian, Spain, Ernesto asked Lord Cowdray to intercede with the Foreign Office in order to dispatch a cable of protest over Huerta's imprisonment of three other Maderos. Cowdray again complied and requested to meet Madero whenever he might be in London.[28]

Occasionally, these petty courtesies became burdensome, as in the case with Aurelio Melgarejo. The Pearson group in Mexico had been retaining attorney Melgarejo, who in February of 1914 received President Huerta's appointment to serve as the Mexican minister to Colombia. Melgarejo had already forced a doubling of his retainer, saying that he could influence oil legislation. Now, however, he asked Lord Cowdray to cover the entire cost of his post in Colombia. Cowdray was embarrassed by the request but felt compelled to comply "without too great a tax," if only to prevent Melgarejo from becoming an enemy. The Pearson group later were relieved when the fall of the Huerta government allowed them to dismiss Melgarejo's services completely.[29]

The oil companies were soon drawn into Huerta's fiscal problems, for he had to fight against zapatistas in the south and constitucionalistas in the north. As a consequence, the Madero federal army of fifty thousand troops grew under Huerta to more than two hundred thousand. Counting the rebel armies of Obregón in the west, Villa in the north, Pablo González and Aguilar in the east, and Zapata in the south, Mexico now had a lot of men — and some women and children, if the Casasola photos are to be believed — under arms. These struggles began to extract a greater economic toll than had the (comparatively) parochial

rebellions of the Madero period. The deteriorating economy did not provide the revenues for burgeoning federal expenditures. Moreover, the peso was losing its value. It slid from a conversion of fifty centavos to thirty-six centavos to the dollar within five months of Huerta's taking power. Prices rose, and government employees and federal troops experienced delays in receiving their pay. President Wilson's refusal to recognize his government prevented Huerta from securing a loan in the United States.[30]

Thus, Huerta turned to Europe for a loan, and it occurred to him that Europeans with businesses in Mexico ought to be delighted to help him. The foreign minister asked Body to seek Cowdray's assistance in securing a one-hundred-million-peso loan. It was suggested that a number of businessmen could help with one million pesos each. Cowdray replied that he would be willing to underwrite a million pesos provided that banks would take up one-half of the loan. Cowdray then contacted José Yves Limantour in Paris, who already had considerable contacts in European banking circles. Eventually, Huerta secured a loan of £ 20 million with the Banque de Paris, of which £ 6 million was dispatched immediately. Limantour's old financial associates at Spreyer acted as brokers, earning a handsome commission. Cowdray later admitted to having participated in 3 percent of this Mexico loan, meaning that the Pearson group purchased several thousands of pounds sterling of Mexican bonds.[31]

Such "requests" by unstable Mexican governments placed the foreign businessmen in a dilemma not inconsistent with their involvement in domestic politics. Should Cowdray have saved precious capital by refusing to subscribe to the loan and risk incurring the wrath of the Huerta government? Was a politically unstable Mexico really a good risk for additional investment? A Pearson group memo on the Mexican foreign debt listed £ 39,481,800 in government loans and £ 190,940,700 in railway bonds and direct foreign investment (see table 7). Cowdray did the right thing: he equivocated. He contributed just enough support not to "make enemies," as he so often said of his business diplomacy.

The reluctant contributions of the foreign businessmen, however, did little to satisfy Huerta's financial problems. He was still forced to increase taxes. His "friends" in the foreign business community were forced to pay them. Huerta doubled the stamp tax and increased the import tax by 50 percent. Apparently, he even assessed a forced loan of 7,500 pesos on Waters-Pierce, whose chairman, Henry Clay Pierce, had been having difficulty getting close to the Huerta regime. Huerta

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

then "fined" Huasteca $400,000. American diplomats suggested that Doheny's company not pay it, and Huasteca resisted at the risk of jeopardizing its business. The fine was pending throughout Huerta's term of office.[32] All the foreign businessmen resisted these new exactions. Cowdray cabled his protest to proposing a 10 percent tax hike, which the Mexican Senate approved anyway. Oilmen at Tampico calculated that Huerta's tax increases, amounting to seventy-five centavos per ton of exported oil, now equaled 50 percent of the oil's price at the well head, according to these calculations:[33]

|

To add insult to injury, Huerta's customs officials insisted on collecting these duties in U.S. currency rather than the deteriorating Mexican peso. Months later, the Huerta government decreed additional tax increases, raising the bar dues to one peso per ton. Perhaps stung by U.S. diplomatic hostility, Huerta even suggested that the oil industry, which exported so many Mexican resources without benefit to the nation, ought to be nationalized. Incensed American oilmen converged on Mexico City to protest the tax increase. Even Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan dispatched a stiff protest to a Huerta government he did not recognize.[34]

The increased taxation failed to solve Huerta's financial problems. Ultimately, he suspended payment on the national debt, as the peso slipped to a value of twenty-nine cents.[35] These fiscal maladies tended to dampen the ardor of the foreign community toward Huerta. They also motivated an essentially reactionary Huerta regime to propose nationalizing the Mexican oil industry.

Huerta did nothing to discourage the continuation of the bickering and rumor mongering among the oil competitors. Waters-Pierce did not see any advantage at all in Huerta's ascension to power and mounted a relentless press campaign to identify Cowdray as the chief patron of "the Usurper." American and Mexican newspapers reported a litany of spectacular charges:

that Lord Cowdray helped Huerta overthrow Madero;

that Cowdray had brought about the British recognition of Huerta;

that he had arranged the loans for Huerta's government;

that he had placed his man, Sir Lionel Carden, as ambassador to Mexico;

that Sir Lionel, as Cowdray's surrogate, criticized Wilson's policy toward Mexico;

that Huerta gave El Aguila new oil and railway concessions;

that Cowdray was about to sell his interests to Standard Oil; and

that Huerta was to nationalize Mexico's oil lands in order to transfer them to Cowdray for $50 million.[36]

Cowdray personally countered the rumors by writing corrections and protests to editors, but much of the damage had already been done.

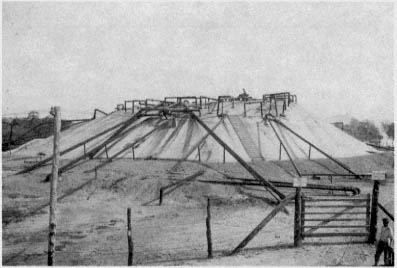

Fig. 10.

Concrete mound protecting Potrero No. 4, 1916. Following the nearly

disastrous fire at this prolific well, El Aguila constructed a concrete mound over

the well head and drained off the volatile gases. the cavity of the mound could be

filled with water and steam during thunderstorms to prevent another bolt

of lightning from igniting the gases. from the Pearson Photograph Collection,

British Science Museum Library, London, courtesy of Pearson PLC.

The State Department was certain that Cowdray's influence had obtained British diplomatic recognition for Huerta and that the British oilman was reaping great material benefits from Huerta.[37] Pierce became enraged when in November of 1913 he had not been reelected to the board of directors of the National Railways bondholders in New York. An article in the New York Herald recounted how Lord Cowdray had used his influence in the new government to deny this post to his old rival. Cowdray was at his wits' end. "[U]nless [Henry Clay Pierce] is prepared to be friends all round," Cowdray warned, "we will break the [sales] arrangement now existing — which was made at his request — and go for as much of the Domestic Trade as it is possible for us to obtain." Lord Cowdray suspected that Pierce's agents in Mexico were Shelburne Hopkins, who later admitted as much, and José Vasconcelos.[38] Their own economic competition seemed to draw the foreign interests into the whirlwind of Mexican revolutionary politics.

The Most Difficult Moment

The problem was that oilmen were forced to choose between so many conflicting authorities during the Revolution. The military factions that controlled certain areas of Mexico always took it upon themselves to collect the taxes and issue permits, denying jurisdiction to other domestic powers, no matter which of them happened to occupy the national palace in Mexico City. Oilmen who sold to the internal market had to deal with different factions in each sales area. In the fields, they often had to treat with two factions at once, one collecting export taxes at the ports of Tampico and Tuxpan and the other controlling the oil patches. The oilmen reacted as best they were able.

The confusion of authority began soon after Huerta took power, when the Constitutionalist forces loyal to Venustiano Carranza first invaded the oil fields. In May, General Lárraga and two hundred troops appeared at El Ebano. He arrested the superintendent, helped himself to supplies, exacted a "loan" of five thousand pesos, and went away with all the rifles in camp.[39] Gen. Cándido Aguilar arrived in the southern fields in November and ordered the cessation of drilling and pipeline operations. He demanded the payment of two hundred thousand pesos to the new military authorities. Within three days, Aguilar permitted oilmen to resume pipeline operations, so long as they did not sell oil to any of the Mexican railways within federally controlled areas. Local managers were forced to shut in their prolific wells at Potrero del Llano, Alazán, and Naranjos. Around the mighty Potrero No. 4, the gas pressure soon broke fissures through the ground. It was this damage, oilmen said, that led to the three-month conflagration that nearly destroyed El Aguila's great well.[40]

Aguilar also demanded a tax payment of fifty thousand pesos from the Huasteca oil fields, although he later accepted a payment of ten thousand pesos. Huasteca's operations had not been interrupted, although the Aguilar forces confiscated all the arms in the Huasteca camps. Still, Huasteca was not a company that relished paying taxes to two authorities. Harold Walker suspended tax payments to the federal government at Tampico, a tactic justified by the U.S. failure to recognize Huerta. Subsequently, when Walker was in Mexico City on business, Huerta threatened him with death. Walker promptly signed a draft for one hundred thousand pesos to cover the unpaid federal taxes.

Once Walker was safely out of the city, the company then canceled payment on the draft.[41]

Most of the Waters-Pierce assets remained in Tampico, still controlled by Huerta's troops. Therefore, Pierce was worried when the Constitutionalists ordered him to discontinue fuel oil deliveries to Huerta's troop trains. Knowing of Washington's attitude toward Huerta, Pierce asked for U.S. protection, going so far as to notify the State Department of the location of his refinery, storage tanks, pipelines, oil wells, and floating craft. Was he expecting — or hoping for — a U.S. invasion? Upriver at Pánuco, Shell's employees of La Corona Company had strict orders not to meddle in Mexican politics. Yet, now La Corona too was confronted with a problem of knowing to whom to pay oil taxes. Should it pay to the Constitutionalists, whose troops occupied Pánuco after December 1913, or to Huerta's troops still in Tampico?[42]

All of the oilmen had to use their best diplomacy in order to placate all the parties. They also had to avoid alienating competing political factions but at a reasonable cost. El Aguila's managers desired to operate with both the Constitutionalists and Huerta. Therefore, they decided to pay Huerta's new taxes — even though existing contracts gave them tax exemptions. Meanwhile, El Aguila, Huasteca, and Waters-Pierce all acceded to General Aguilar's orders not to sell fuel oil to Huerta's railroads.[43] To complicate matters, Huerta's federal troops retained control of the isthmus, where El Aguila had a refinery and several minor oil fields. General Aguilar, a Constitutionalist, summoned J. B. Body to his headquarters at Tuxpan to pay a $120,000 tax bill on the isthmus properties. Body sent his vice president, Ryder, to temporize with the Constitutionalist commander. Body also saw fit to leave Tampico just before the arrival of Carranza, after that city had fallen to the Constitutionalists. He did not wish to arouse Huerta's suspicions. At the same time, when it appeared likely that the Constitutionalist rebellion was going to succeed, the oilmen scrambled to sell fuel oil to Carranza, so as not to appear partisans of Huerta. Then Carranza ordered El Aguila to halt deliveries of oil from Tuxpan, held by constitucionalistas, to its refinery in Minatitlán controlled by the huertistas. In response, the huertistas prevented the refined products of the Minatitlán refinery to pass into Constitutionalist-held territory.[44] Few companies were immune from this domestic struggle for power during the Revolution. The National Petroleum Company of Richmond, Virginia, had been leasing land from the National Railways of Mexico. When the rent came due, the Constitutionalists demanded payment be

made to them. So did the Huerta government. The dilemma was shortlived, however, as the Constitutionalists soon took complete control of the National Railway system.[45]

Such problems for oilmen even outlasted Huerta, because the Constitutionalists did not recognize any contracts that oilmen had made with the huertista government. Both Jersey Standard and Shell officials had built riverside storage and terminal facilities while Huerta controlled Tampico. After the Carranza troops took over, both companies had to present their "illegal permits and contracts" to Tampico's new officials.[46] In the meanwhile, Huasteca had made an agreement with the Constitutionalists to supply their fuel oil needs during their struggle with Huerta. The value of these supplies was to be used to defray the future payment of taxes to Carranza. Carranza's need for funds became acute soon after Huerta's fall, when Villa and Zapata occupied Mexico City. Carranza's agents ordered Huasteca to pay them 665,000 pesos in back taxes. Huasteca declared that it had already provided the Constitutionalists with 685,000-pesos-worth of fuel oil, essentially paying these taxes in advance. Cables passed from Huasteca's New York attorney F. R. Kellogg, the secretary of state, and the British ambassador in Washington. Their diplomatic intervention helped resolve the matter.[47] Once they realized that the Carranza victory did not end the domestic political conflict (for Villa and Zapata immediately rebelled against the new government), the oilmen openly expressed nostalgia for a simpler time — the era of Porfirio Díaz.

The longer these conflicts continued, the more the oilmen sought refuge with a new ally, the diplomatic community. They did so in violation of their Mexican government contracts and permits, almost all of which treated the companies as if they were Mexican entities. In disputes with the government, the companies were to seek remedies in Mexican courts, not with foreign governments. Of course, the Mexican court system was deteriorating as rapidly as the domestic political situation. Oilmen naturally turned increasingly to their home governments. Diplomatic support had been nearly nonexistent during the Díaz regime. Indeed, it had been unnecessary. Revolutionary times provoked more diplomatic activities in defense of the oilmen. Domestic factions least in favor with the foreign governments were encouraged to wrap themselves in the cloak of nationalism. It was a refuge of sorts for an increasingly beleaguered Victoriano Huerta. American, British, and even Dutch gunboats appeared off the shores of Tampico and Tuxpan in order to "defend" the lives of foreigners. Some managers of the

Dutch company, La Corona, began to live aboard the Dutch cruiser Kortenaer. Dutch marines and the ship's crew worked for La Corona, because many of the skilled workers had fled.[48]

Without having been asked, the Dutch even attempted to mediate between the Constitutionalists and Huerta. One Dutch businessman laid before Huerta a plan for immediate elections approved by the American secretary of state. President Huerta was indignant. He cursed the American president and his new diplomatic representative in Mexico. He also deplored the presence of foreign naval vessels at Veracruz and Tampico. "No one has the right to intervene in our domestic politics," Huerta shouted, "and if the United States continues to do so — then I will defend the honor of Mexico as long as one Mexican is still alive." Reported the chastised mediator to the Dutch foreign minister: "That, Excellence, was the most difficult moment I have experienced in my life."[49]

More and more, the petty vexations aroused a desire among oilmen for some diplomatic or even foreign military solution. Other companies had followed Waters-Pierce's example of informing the U.S. government of its valuable installations, presumably so that these would become an integral part of the military plans should an American invasion come. Even the British and Dutch were half expecting U.S. intervention. Given President Wilson's disgust for the Huerta regime, British and Dutch businessmen felt that the United States was obliged to protect non-American properties too. Everyone wanted to avoid in Tampico the kind of looting of the foreign community that had occurred after Villa's troops took Torreón. The Dutch and British ambassadors in Washington said they held the United States responsible for any damage the Constitutionalists might inflict, since Wilson and Bryan were backing Carranza and Villa. El Aguila began to take precautions. "My dear Hugh," Cowdray wrote to the commander of the HMS Essex, introducing him to Body in Mexico, who was to "tell you the nearest way to our oil fields in the event of trouble arising, so that they can be adequately protected."[50]

Clearly, the demand was mounting for some kind of resolution of the unsettled situation in Tampico. But the oilmen were hardly of one mind about what should be done. "Does not the situation appeal to you as one in which our Government should see that its citizens should not be despoiled of their property?" the National Petroleum Company asked Secretary Bryan.[51] But El Aguila looked upon military intervention with horror. "We know that if the United States decides upon

intervention as one way of dealing with the situation," Body observed, "no foreign life or property will be safe."[52] Intervention is what they got; but it was to be intervention of the American government's choosing — not the oilmen's.

Seize the Custom House

Tension had been mounting between the federal troops of President Huerta in Tampico and the Constitutionalist forces operating in the surrounding environs. The British government recognized Huerta. The American administration openly supported the Constitutionalists. Foreign oilmen became involved insofar as they needed to operate with all parties and as they represented an increasingly substantial source of revenues for contending factions. Perhaps an explosion was not inevitable, but the revolution in the Huasteca Veracruzana was as volatile as some of the belching oil wells. A local spark (struck by a nervous foreign manager) or a bolt of lightning (sent down by diplomatic misstep taken thousands of miles away) might have been enough to set off a political conflagration consuming the entire oil industry. The Tampico incident was almost it.

For several months before the spring of 1914, Constitutionalist and federal troops had engaged in sporadic skirmishes around the city of Tampico. To protect foreign property and life, the gunboats of the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands cruised up and down the Pánuco River among the oil barges, tank steamers, and federal gunboats. The battleship USS Virginia had been stationed two miles off the entrance to the harbor.[53] By November of that year, the Navy Department had been making contingency plans. Rear Admiral Frank F. Fletcher had reported no fighting or disruption of the oil industry as yet but estimated that the Constitutionalists had 4,000 men in the district while the Federalists had a force of 1,500 men at Tampico. Fletcher had drawn up plans to place 3,500 American servicemen with machine guns, field guns, and one-pound mortars into the field to protect the oil installations. On one occasion, the Americans had even ordered the evacuation of its citizens. In December 1913, when three thousand troops under General Aguilar took up positions on the Pánuco River opposite Tampico, approximately five hundred evacuees, including two hundred Chinese, gathered for evacuation. Gunboats

ferried the first refugees to the battleships Virginia, Rhode Island, and New Jersey lying offshore.[54] The action turned out to be somewhat precipitate, and the Americans soon returned to work.

The Constitutionalist siege of Tampico began in earnest on April 7. A force under Gen. Luis Caballero probed, somewhat desultorily, the federal defenses at the railway trestle just north of the city. Meeting resistance, the Constitutionalists fell back. Federal gunboats also fired back at rebel positions in the southern industrial suburbs of Doña Cecilia and Arbol Grande. Their shells landed near the Pierce refinery, setting fire to two oil tanks and a warehouse. Some foreigners were brought aboard British and American naval craft, and the German cruiser Dresden arrived to protect German nationals. Meanwhile, Aguilar apparently had menaced El Aguila's oil fields because of Lord Cowdray's alleged support of Huerta.[55] To this point, no group of foreigners had as yet been singled out for reprisals by any of the combatants. But the situation was tense.

The feverish activity of the American naval vessels had consumed their supply of petrol. As the city lay nervously under siege, the U.S. gunboat Dolphin dispatched its paymaster and a crew aboard a small whaleboat flying the American flag. The American refineries were now closed for business, and this crew rowed along the river and up a small canal to the wharf owned by a German merchant in order to buy gas. They landed within blocks of the northern railway bridge, where the Federalist forces were expecting a Constitutionalist advance. Once onshore, the American sailors were arrested by federal troops and held at gunpoint for one hour. American naval officers notified the federal commander, Gen. Ignacio Morelos Zaragoza, who promptly released the men with his profound apologies about the misunderstanding of his subordinate officers. The American sailors returned to their gunboat with a cargo of gasoline.[56]

Cables passed between the American naval commanders at Tampico and Veracruz and their superiors in Washington. Admiral Henry T. Mayo demanded that General Morelos Zaragoza order his forces to fire a twenty-one-gun salute to the offended American flag. The American government also demanded that President Huerta compel his commander to comply. To some in Mexico City, Huerta almost seemed to welcome U.S. intervention as the only way he could rally enough support to shore up his weakening government. Huerta's defiance motivated the secretary of the navy, Josephus Daniels, whose assistant secretary at the time was young Franklin D. Roosevelt, to dispatch six

Map 3.

Tampico in 1918

more battleships to Tampico.[57] Were Daniels and Roosevelt recreating the momentous decision of Uncle Theodore Roosevelt, who as assistant navy secretary in 1898 and on his own authority sent Admiral Dewey's fleet to Manila? Apparently not. The decision to "get tough" with Mexico had come from President Wilson himself. At the time, Wilson told his personal physician and golf partner: "I sometimes have to pause and remind myself that I am president of the whole United States and not merely of a few property holders in the Republic of Mexico."[58] Cooler heads did not prevail. It soon became clear that no one was thinking at all about the oil industry in Mexico nor about the Americans who worked there.

An armed invasion of Mexico was ordered. Instead of having the marines storm ashore to protect the oil fields of the Huasteca Veracruzana and the refineries of Tampico, the Wilson administration sent the expeditionary force to the port of Veracruz. Naval planners had contemplated an invasion or at least a bombardment of Tampico. But their inability to sail their battleships across the sandbar at the mouth of the Pánuco River deterred them. Admiral Mayo worried that his smaller gunboats and cruisers on the Pánuco River would be susceptible to Mexican artillery fire. American policymakers had chosen Veracruz because Huerta still obtained arms and supplies

through the port. An American interdiction of the Veracruz port — although not invited by Huerta's principal adversary, Carranza — was intended to rid Mexico of this "tyrant" and "assassin" once and for all. A report that the German cargo vessel Ipiranga was nearing Veracruz sealed the decision. The Americans did not want Huerta to obtain arms.[59]

In the haste of decision making, officials in Washington dismissed the danger that armed intervention posed for U.S.-Mexican relations or for the relationship between Americans working in Mexico and their hosts, the Mexican people. No one, for example, had queried the American consul at Tampico, Clarence A. Miller. He would have warned that a troop landing at Tampico or Tuxpan would lead to the Mexicans' destroying all the oil fields, tank farms, pipelines, and refineries in the district. "A war of American intervention would be a great calamity. All other nations will stand to reap all the advantages; whatever the result might be," he warned; "our country would bear all the expense and reap all the crop of resulting hatred and vengeance. Americans will be unable for many years to come to work in the outlying districts in the oil fields and other parts of Mexico."[60] Miller had not even considered what would happen in the oil zone if American troops landed at Veracruz instead.

The navy's plans to protect the oil fields remained on the shelf. Instead, Daniels cabled his admirals: "Seize custom house [at Veracruz]. Do not permit war supplies to be delivered to Huerta government or to any other party."[61] By the second day of the invasion, by which time the Congress had approved Wilson's action, more than 3,300 American troops were ashore at Veracruz. The German merchant vessel Ipiranga was indeed detained by the American occupation of Veracruz. But the invasion forces, not being at war with Germany, could not confiscate the cargo. Once allowed to depart, the Ipiranga headed for the federally held port of Puerto México, where the arms were off-loaded for Huerta's troops.[62] The Americans could not even prevent the shipment of arms to Huerta, which had been the ostensible excuse for seizing Veracruz.

As soon as the news spread along the Mexican Gulf Coast that the United States had declared war on Mexico (which was not true), all American gunboats pulled out of the Pánuco River and sailed to Veracruz. The Americans at Tampico were stunned. Within hours, refugees with white skin began descending on Tampico from the oil fields. Englishmen, Dutchmen, and Germans accompanied the Americans. Europeans had little faith that the Mexicans, at the moment, cared about the differences between the nationalities. As the American workers saw it, "Brown howling mobs, armed with clubs, stones and pistols, immediately congregated all over the city, parading the streets and howling for 'Gringo' blood. To a Mexican everything with a white face is a hated `Gringo.'"[63] The fearful Americans gathered at the Southern Hotel, where they bolted the doors against a mob of Mexicans who had gathered to wreck Sanborn's American Drug Store. No doubt, the Mexicans were not calmed by the sight of the American flag waving above the Southern Hotel. Finally, the German commander of the Dresden and a detachment of German marines marched on the hotel, where the Americans were trapped. The Germans gained the cooperation of the federal commander and escorted 150 Americans to the waterfront, where they were evacuated. The Americans credited the Germans with having saved them from being overrun by Mexican "mobs."[64] It was a curious exchange for the U.S.'s presumption of having intercepted a German merchant vessel during peacetime.

The American naval commander, Admiral Charles T. Badger, later considered this withdrawal of the gunboats from Tampico to have been a grave error. If the gunboats had subsequently returned to save the Americans, they would have come under fire by both federal and rebel

forces, because the navy's reappearance at Tampico would have been a provocation.[65] Indeed, the British and German commanders cautioned the American vessels not to return. They requisitioned the barges and tankers belonging to the Huasteca and El Aguila oil companies, raised the German and British flags over them, and evacuated Americans as well as their own citizens.[66] In any case, the withdrawal of U.S. gunboats from Tampico had had the approval of the Navy Department. Secretary Daniels stated that he did not want the Mexicans to think that the United States was at war, he did not desire to endanger all foreigners at Tampico, and anyway the British naval commander had agreed to protect American citizens. Indeed, the commander of the Kortenaer, which arrived in Tampico to take on the Dutch citizens from the Dresden, was certain the Mexicans would have destroyed the oil industry if the American forces had reappeared in the river. In fact, he was concerned that the Constitutionalists might destroy the wells anyway.[67]

Glad Enough to get Out

In the meantime, panic had spread among the American and European workers. American drillers at Pánuco heard rumors of an imminent landing of U.S. troops and did not want to be caught upriver. The Texas Company sent "a big stern-wheeler" steamboat to Pánuco. Coming downriver with a load of Americans, the British pilot, flying the Union Jack, warily floated past the federal gunboat. The Mexican gunboat did not fire. The Americans on board had been expecting to see Leathernecks scampering along the riverbanks to rescue them. None came. The Chinese employees who stayed behind at Pánuco packed up the tools and took them to the British consular office for safekeeping.[68] Many left their personal effects behind. A blacksmith working for Mexican Gulf at Pánuco left behind his own set of tools, valued at $165. Not choosing to return, he later sent for them, only to discover that the tools had been pilfered in his absence. "At the time all the Americans were glad enough to get out themselves," the worker later wrote to the U.S. consul.[69] The American evacuees boarded a mixed flotilla of merchant vessels and oil tankers off the coast. Naval officers came on board to draw up passenger lists, and the entire group was dispatched to Galveston. Apparently only one American had died. Weston Burwell was killed while en route from Pánuco to

Ozuluama, carrying four thousand pesos to purchase mules in order to build an earthen reservoir for La Corona. In all, some two thousand oil workers and family members had clambered aboard the ships bound for Galveston.[70]

The recriminations began immediately. Those refugees who had either returned to their hometowns or stayed for a month at Galveston complained of the shabby treatment they had been accorded by U.S. forces in Mexico. President Wilson and Navy Secretary Daniels came under special criticism. The oil field and refinery workers grumbled about the navy's retreat from Tampico just when U.S. forces were attacking Veracruz. They felt their lives had been endangered and their personal property lost because of their government's perfidy. The refugees certainly were not philosophically against the notion of U.S. intervention in Mexico. In fact, many would have welcomed the marines at Tampico; they even demanded that U.S. military forces protect them on their return to the oil fields. Somewhat defensively, Daniels asked why these Americans were protesting a policy that had saved their lives. They had gone to Mexico to get rich, he suggested, and now expected the country to raise an army of five hundred thousand men to protect them.[71] Perhaps no one reflected the sentiment of the American petroleum workers in Mexico better than William F. Buckley. He continued to be a bitter critic of the Wilson administration. At the 1919 Congressional hearings on Mexico, he claimed that the American troop landing at Veracruz had needlessly endangered lives at Tampico.[72] Thereafter, the American workers in Mexico, as well as the owners, were to form a vocal lobby against what they considered Wilson's inept foreign policies.

For the moment, however, the owners of oil companies withheld their criticism, needing diplomatic support to protect their abandoned properties in Mexico. The big question concerned the oil leases. The American companies would not be able to make their rental and royalty payments to landowners during their exile. Lack of timely payment often meant breach of contract, and they feared that the British and Dutch would jump American claims. Some Americans even feared that the British gunboats might collude with British oilmen to prevent the return of the Americans. They looked to the secretary of state for help.[73] Secretary Bryan conferred with British and Dutch diplomats in order to prevent the breach of American-held leases. The Dutch and British oilmen, as it turned out, were quite willing to agree to a policy of status quo ante. They too had evacuated Tampico and were not will-

ing to return until the Americans did. Their leases were in the same danger of being breached. The British government queried Lord Cowdray, who disclaimed any interest in taking advantage of the Americans' plight. The Dutch government also agreed to withhold any diplomatic support to Dutch citizens who sought to jump American leaseholds.[74] Once again, the fate of the Mexican oil industry was decided outside the country.

The owners of oil properties in Tampico, of course, expected the worst. They were certain that the evacuation and lack of U.S. military protection would mean the destruction of the oil fields. A representative of the East Coast Oil Company painted a mental picture of Mexicans looting the oil fields, runaway wells catching fire, and destroyed and burning oil camps.[75] "The oil field of Mexico is gusher country,", said a representative of The Texas Company, who warned of the danger of "unsupervised" wells filling up the storage pits and then "spreading over the lands and streams." The danger of fire grew with the oil spills. "Such a fire would burn the entire oil country and doubtless a multitude of its inhabitants," he said. Conflagration would also melt the valves of those wells that were pinched in, causing additional losses.[76] Of course, these owners were asking, rather indirectly, for an American military escort so that the oilmen could return to Mexico.

Destruction of neither the oil wells nor the oil camps ever took place. Some oil managers had stayed on their properties. William Green of Huasteca later bragged that once ordered out to sea, he returned by boat to the oil wells in the Faja de Oro, which he managed for thirty days until the U.S. government permitted the return of the American workers.[77] Indeed, the feared looting consisted of only a few mules and automobiles taken by Constitutionalist troops. For the most part, the refineries were untouched, and the Mexican workers in the oil fields prevented the wells from overflowing the storage capacity. The American consulate reopened in Tampico on 4 May, just thirteen days after the evacuation, protected by the forgiving attitude of the federal troops still in the city.[78] The State Department had sought to minimize the danger to the oil zone but not by dispatching U.S. troops to protect the wells. Instead, Bryan attempted to negotiate separately with the Constitutionalists to declare the oil zone a neutral area in its revolutionary struggle with the federal forces. Carranza's answer was somewhat noncommittal. The neutrality of the oil zone, he said, depended on Huerta's leaving.[79]

Once again, the Pearson group attempted to make friends on all sides. "I have maintained very cordial relations with [American forces at Veracruz]," said J.B. Body, "but not to such an extent as to run the risk of being called to account by our Mexican friends at some later date."[80] All El Aguila coastal craft struck their Mexican colors and hoisted the Union Jack so as not to be captured as war prizes by the American navy. Meanwhile, the British naval officers at Tampico traveled into the oil fields, speaking to both Constitutionalist and Federalist commanders about protecting the volatile oil wells. The English managers remained in most of the oil camps; El Aguila's pipelines continued pumping crude oil, which its fleets carried to the refinery at Minatitlán. The only Pearson asset in transition during the aftermath of the Tampico incident was its Tehuantepec National Railway (TNR). Huerta's federal army took control of the TNR, which Mexican workers had operated when American workers evacuated.[81] Operations of the British company continued.

The Americans, however, were out for most of May, during which time the Federalists had surrendered Tampico to the Constitutionalists. They began to return on 20 May, just a month after they had left, and within five days, the steam tankers resumed loading petroleum at the Huasteca terminal.[82] In Tuxpan, June was another record-breaking month for oil exports. General Aguilar maintained order in the city for Americans and occupied himself with collecting a 15 percent tax on all Mexican properties. In Pánuco and Topila, however, in the absence of Constitutionalist troops, the local citizens greeted the returning Americans with anti-American meetings and insults. Several citizens of Pánuco demanded that Americans turn over their weapons and be treated as spies.[83] Many Mexican citizens in the Huasteca remained hostile while the American troops still occupied Veracruz. They did not leave Veracruz until November 1914, fully four months following the collapse of the Huerta government. Like the Americans earlier at Tampico, Huerta fled to safety aboard the German cruiser Dresden. The Constitutionalists and the Federalists had shown great forbearance while American troops occupied Tampico. Both Mexican factions had found it in their interest not to destroy the oil industry, because as Navy Secretary Daniels was fond of saying, it was "the goose that laid the golden egg." Both sides needed the revenues provided by the oil fields. As for the American intervention at Veracruz, it did not seem to have accomplished very much at all except to promote the resentment of Mexican combatants toward Americans. The oil zone would never

return to normal following the Tampico incident. One colonist from Tampico said later that until the Veracruz occupation, Americans on the Gulf Coast had experienced some inconveniences.[84] Thereafter, all foreigners were molested aplenty.

Showing Signs of Unrest

Although the oil companies had already suffered from their inevitable involvement in Mexican politics, the American invasion of Veracruz marked the beginning of wholesale depredations in the oil zone. Before April 1914, disruptions had been sporadic and isolated. Thereafter, conditions approached anarchy. Prolonged civil conflicts rendered the booming oil industry the object of attention by a penurious new government, ascending army chieftains, and destitute military deserters. Although these depredations caused countless vexations for the foreigners and Mexicans running the oil industry, little real damage occurred to the oil assets themselves. From 1914 onward, the prices increased at the same time that new drilling yielded record flows of crude oil. Most leases had been taken before that date anyway; most pipelines and oil terminals had already been well established. Refining and exporting continued almost unimpeded by the civil turmoil, except (as we shall see in chapter 5) for brief moments of labor unrest. The depredations took place primarily in the countryside. Both foreigners and local Mexicans working in the oil fields suffered robberies, hold-ups, insults, intimidations, indignities, ravages, forced loans, and assassinations. These were not part of a revolutionary program but a result of the breakdown of law and order in the Huasteca. Although revolutionary depredations made life insecure in the oil fields, they hardly affected the performance of the foreign-owned industry.

After the fall of Tampico, there were just two more pitched battles in the oil zone, both at El Ebano. No sooner had Huerta fallen than the combined forces that had brought about his government's demise began to break up. The old federal army of Porfirio Díaz and Victoriano Huerta was destroyed. Now the victorious Constitutionalist forces broke into competing factions. Villistas and zapatistas fell out with carrancistas and obregonistas. Meanwhile, Carranza made Veracruz his capital while the zapatistas and villistas occupied Mexico City. Constitutionalist forces loyal to the first chief held the Huasteca region and

Tampico. In November 1914, a force of villistas under the command of Gen. Tomás Urbina descended from the central plateau along the San Luis Potosí — Tampico rail line. They were met at El Ebano by Constitutionalist forces under Gen. Jacinto Treviño. The battle was joined in the midst of Mexico's oldest oil field. One hundred cannonballs and countless bullets pierced the oil storage tanks. Smokestacks of the topping plant were shot off. Water and oil pipelines were broken, and the crops and livestock were looted. Doheny's Mexican Petroleum Company lost eight hundred thousand barrels of oil, none of which had caught fire because it was so thick. Mexican Petroleum also had to buy foodstuffs from Texas to make up for the loss of agricultural production.[85] The villistas did not abandon the area until a second battle, this time fought near but not in the oil camp. In April 1915, a Constitutionalist force of 1,500 men under General Lárraga, a local landowner, cut the railway line between the villistas at San Luis Potosí and General Urbina. Then they pushed Urbina's forces north out of the region.[86]

While in the oil zone, the villistas attempted to wield some influence over the industry, adding to the administrative confusion. A certain E.J. Eivet of the Conventionalist (Villa's) Railway was having difficulties securing fuel oil from the Constitutionalist-held oil fields. The villistas had been forced to purchase fuel oil in Texas. In Mexico City, Eivet called Frederick Adams of the Pearson organization on the carpet. He demanded a fifty-thousand-peso "loan" in exchange for good treatment when the Convention triumphed. The Pearson group declined to pay the loan; it pleaded neutrality in political conflicts. Eivet threatened that Pancho Villa himself would be interested in knowing who his enemies were.[87] Even after the second Ebano battle, General Urbina menaced the oil zone once again. "We are not all dead, but having a good time," he was reported to have said during a banquet. Urbina boasted that he could capture Ebano, and Pánuco too, anytime he wanted. Perhaps he wanted the Constitutionalists to divert troops from Celaya and Aguascalientes, where they were pressing the villistas, to defend Tampico.[88] Perhaps Urbina was merely posturing, mocking defeat with characteristic bravado. In any case, the villistas soon abandoned the oil region to the constitucionalistas during the weeks that Gen. Alvaro Obregón drove Villa's army north through the central plateau.

Only one other time, besides the Veracruz invasion, did the foreigners have to evacuate the oil fields en masse. This occurred in 1916, during the second U.S. armed intervention in Mexico, when a detachment

of U.S. forces was sent into Chihuahua to punish Pancho Villa for his raid on Columbus, New Mexico. Unlike the first crisis, this one lingered at low intensity during the eleven months that U.S. forces were in Mexico. At the time, labor unrest was building tensions within the city of Tampico. The Constitutionalist military authorities, in their disgust for the presence of U.S. troops on Mexican soil again, now had a perfect excuse to make common cause with the Mexican working class. A rumor passed through the city that the police chief was planning to have all the Americans killed or captured before they could reach the safety of U.S. gunboats, which had quietly returned to the Pánuco River. Once again, Americans were disarmed at roadblocks throughout the oil zone, and Mexican soldiers around Tampico mounted guns on the jetties and railway flatcars. Shortly after midnight on 15 May 1916, soldiers surrounded the refinery of the Standard Oil Company. While Mexican officers positioned themselves at the gangplank of the oil tanker John D. Rockefeller, then docked at the terminal, soldiers were seen on launches in the river. A night watchman feared they were laying mines. Then at 4 A.M., according to Standard Oil executives, "Three whistles were sounded from the opposite side of the river, and the Mexican soldiers immediately took to their boats and crossed to the other side."[89] The troops did not commit any destruction of the refinery. Some foreign workers, nevertheless, were so spooked by the incident and the rising level of tension, that nineteen men, eight women, and two children left with the John D. Rockefeller the very next day. The indignant refinery manager, J.A. Brown, claimed that "they stampeded."[90]

As usual, the oil companies prepared themselves as best they could against the political hurricane over which they had no control. El Aguila planned to place the Mexican supervisors in charge of the oil fields if the Americans invaded. The British managers feared that the American troops would be content to secure the refineries and oil terminals on the coast and not the great oil wells just thirty miles inland. Ryder's chief Mexican assistant, Múñoz, was to take charge at Potrero, and other oil companies planned similar contingencies.[91] British citizens were carrying translations of their passports to identify themselves to Mexicans unable to differentiate a London accent from a Texas twang. Although local commanders assured the Britons that no British-owned property would be harmed in the event of an American invasion, the Carranza government notified the diplomats that all oil wells would be destroyed. The British, of course, were concerned to prevent any disruption to the world's supply of petroleum during the world war. The

new American secretary of state, Robert Lansing, responded to British concerns. He promised that his government had no intentions of invading the oil fields.[92] In Tampico, British officials had effected a less tense relationship with the local commander, Gen. Emiliano Nafarrete. The commander calmed the labor upheavals of the first three months of 1916, and he assured British citizens that he would protect them.[93]

By this time, everyone suspected that U.S. troops might also be dispatched to the oil zone. The Constitutionalist authorities now moved their offices out of Tampico. General Nafarrete warned the American consul that he would burn the oil fields if U.S. troops landed at Tampico. Mexican troops covered the lighthouse at Tuxpan bar with black sacks and posted troops at the entrance to the river. All available foodstuffs from the oil camps of El Aguila were ordered to be delivered to Tuxpan. Consul Dawson was a cautious man. He immediately ordered all Americans, with their families and handbags only, out of the oil fields. They were to assemble for evacuation at the Bergan Building, at the Colonial Club (a provocative name for a social club catering to foreigners), and at the Victoria Hotel. Within a week, some 1,200 Americans and a few Britons left Tuxpan for Tampico. Others stayed. Doheny claimed that his ships alone had evacuated 900 Americans. He graciously refused reimbursement from the U.S. government, which as far as records show had offered him none.[94] The 1916 evacuation was brief; the foreigners soon returned.

The British consul at Tuxpan despaired of saving the dangerous situation. He feared that a landing of U.S. troops would certainly mean the destruction of the oil fields. Already reeling from a shortage of foodstuffs, the rural population in the Faja de Oro were made more destitute by this second exodus of Americans. "[T]he people are shewing [sic ] signs of unrest at being without work on account of the Oil Companies having shut down, and do not hesitate to express themselves against the threats made by various commanders to destroy property, etc.," observed British Consul Hewitt. "The people realize that they are dependent in everything on the foreign interests in this section. There are many thousands now without employment and the exodus of Americans is a sore blow to them."[95] Perhaps Hewitt may be faulted for sharing the view of his fellow Britons in Tuxpan-not necessarily that of the Mexican residents themselves. Yet, there is no denying that Mexicans suffered along with the foreigners-indeed more so.

The British Foreign Office, Lord Cowdray, and even some American owners were relieved that the United States did not intend to land

troops at Tampico. For one thing, such an invasion would have had to be "whole hog or nothing," as one British diplomat put it.[96] Cowdray had pressured the Foreign Office to take up his concerns with the State Department. In the event of an invasion, which he counseled against, Cowdray wanted to be able to export through any naval blockade of the Gulf Coast. He also desired American troops to protect El Aguila installations and not to molest company vessels flying the Mexican flag. Nor did Cowdray want his Mexican merchant seamen captured as prisoners of war. As a precaution, nevertheless, El Aguila protected their wells with "armoured mounds"; Penn-Mex next door also placed concrete blocks over the valves of their well heads.[97] If the foreign oilmen avoided getting foreign troops, they did have to contend with the presence of increasingly unruly Mexican government soldiers.

Applying Deleterious Epithets

The presence of troops in the oil zone, as in the rest of the country, contributed to the insecurity of economic and human life in Mexico. Troop depredations began and intensified with the Revolution itself. In the 1911 rebellion against Díaz, marauding bands of armed men operated in the oil zones. They came down the rail line from Tuxpan to sack the oil camp at Furbero, burning railway bridges on the way. Farther north, the El Aguila managers worried about the effect of an armed attack on Potrero del Llano No. 4. Ominously, someone had cut the telephone wires to the camp at Potrero. Cowdray acted prudently. He took out fire insurance, at a premium of 2.5 percent, on 2.5 million barrels of oil per year.[98] Cowdray even suggested that the owner of the Hacienda Potrero del Llano, Crisóforo B. Peralta, who was receiving substantial royalties from the company, ought to organize its defense. "[T]he Peraltas are so largely interested in the Potrero field that they ought to be extremely alert in doing all they can to assist in ensuring its safety."[99]

The series of revolts against Madero, commencing in 1912, brought additional problems of oil-camp security. At the time, El Aguila and other companies were engaged in expanding their pipeline and terminal facilities. None of the companies deemed the political disturbances to be sufficiently dangerous to abandon their construction plans. On the other hand, the oil companies would have suffered more if they had