One

Schools of Scholarship and Corporate Lineages in the Yangtze Delta during the Late Empire

Intellectual historians and social historians of China have much to learn from each other. The world of ideas in Ming and Ch'ing times moved in a historical setting dominated by remarkable social and economic forces. To be sure, such forces were continuations of the economic revolution that began in the middle of the T'ang (618-906) period and climaxed in the striking urbanization under the Northern (960-1126) and Southern (1127-1279) Sung dynasties. During this period the rich delta lands of the south became China's chief granaries, and Southern literati initiated most of the great movements in art, letters, and scholarship that later dominated Ming and Ch'ing civilization.

Economic and cultural resources translated into political agendas. Seventeenth-century clashes between the Ming state and an aroused Confucian gentry led many back to the Confucian Classics to search for political remedies for excessive imperial power. In the Yangtze Delta the Tung-lin partisans of Ch'ang-chou Prefecture (Wu-hsi County) helped to lead gentry efforts to defend their interests against eunuch agents of the emperor. In the eighteenth century the Chuang and Liu lineages in Ch'ang-chou (Wu-chin County) turned to the New Text Classics for alternatives to the political status quo.

We shall discover that between 1600 and 1700 in Ch'ang-chou, the Tung-lin-style gentry alliance was replaced by another social form within which elites were mobilized: Chuang- and Liu-style lineages. Unlike contemporary Europe, where wide kinship ties were relatively unusual, elites in China were forced by historical circumstances to choose

kinship strategies rather than political alliances to protect their interests. Until the nineteenth century, political dissent in China was successfully channeled away from gentry associations and controlled within kinship groups.

Schools of Scholarship

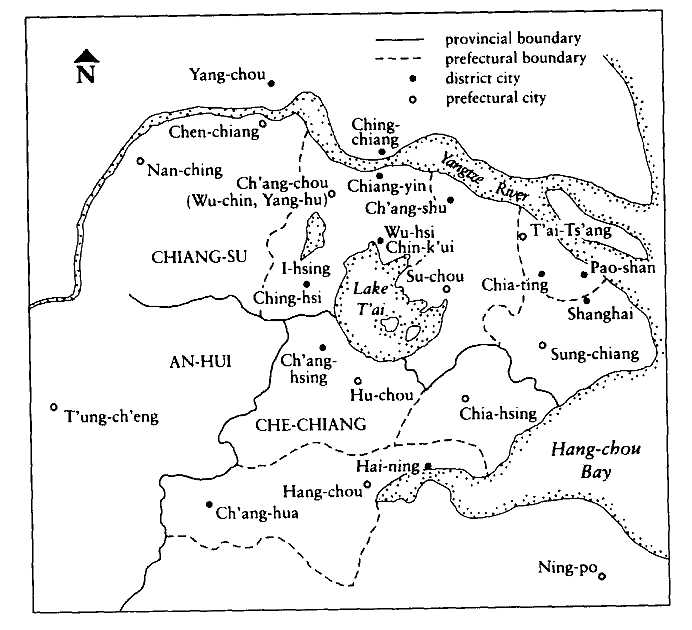

My earlier work focused on the Lower Yangtze River Basin—that is, the core areas of Chiang-su, Che-chiang, and An-hui provinces (map 3)—as the hub of culture, commerce, and communication in late imperial China. My regional approach to the eighteenth-century k'ao-cheng (evidential research) movement and its links to the emergence of an academic community devoted to precise scholarship and Han Learning both helped and hindered historical analysis. Certainly, a macrohistorical perspective permitted me to present the larger regional picture.

In the case of the Lower Yangtze Delta (map 3) such an approach brought to light the cross-fertilization of ideas and research methods among different schools of learning there. Definite unifying features in Han Learning transcended individually defined schools. Despite obvious differences in focus and interest, most schools during the Ch'ing dynasty defined themselves according to shared criteria. These criteria, based on evidential research standards of verification, in turn allowed each school to emphasize its uniqueness.[1]

A macrohistorical analysis by nature must slight lesser components that nevertheless produce important local differences. In my earlier depiction of a "Lower Yangtze academic community" devoted to evidential research, I dealt cursorily with schools of learning within that larger community. Regional subdivisions of the Lower Yangtze macroregion certainly deserve more attention. I propose to provide such attention to the social and intellectual milieu from which the Ch'ang-chou New Text School of Confucianism emerged.[2]

During the Ch'ing dynasty contemporaries themselves classified the diversity of ideas according to schools of scholarship that centered on the Yangtze Delta. School divisions were taken for granted as evidence of the filiation of scholars, who through personal or geographical association, philosophic or literary agreement, or master-disciple relations could be classed as distinct "schools of learning" (chia-hsueh ). Such schools sometimes mirrored the "schools system" (chia-fa ) of the Han

[1] See my Philosophy to Philology , pp. 8-13.

[2] See Skinner, Marketing and Social Structure in Rural China .

Map 3.

The Yangtze Delta (Chiang-nan)

dynasties (206 B.C.-A.D. 220). Han Learning advocates of the Ch'ing appealed to the Han system in their efforts to gainsay the orthodox pretensions of Sung Learning (Sung-hsueh ) proponents. Local schools also represented distinct subcommunities within specific urban areas in the Lower Yangtze macroregion.[3]

It is important, therefore, to recognize that the ideological diversity during the Ch'ing dynasty was usually perceived through the traditional prism of "schools." The real reasons for this diversity are worth exploring further. In the history of Chinese painting, for example, James Cahill has explained that the Che school (in Hang-chou) and the Wu school (in Su-chou) served as centers for historical and theoretical discussions during the Ming dynasty. He has questioned the utility of a distinction between the two schools. Confessing himself to be a "splitter" rather than a "lumper," Cahill concludes that correlations between regional and stylistic criteria in painting were observable and real.[4]

Similar problems arise in any effort to make sense out of the many schools of learning in China during the Ch'ing dynasty. Traditional notions of a p'ai (faction), chia (school), or chia-hsueh are less precise than traditional scholars and modern sinologists tend to assume. In some cases, a school was little more than a vague category whose members shared a textual tradition, geographical proximity, personal association, philosophic agreement, stylistic similarities, or combinations of these. In many cases, a "school" would be defined merely to legitimate the organizations that prepared its genealogy or provided rationalizations for the focus of scholarly activities peculiar to a region.

Nathan Sivin, for example, has defined a school as the "special theories or techniques of a master, passed down through generations of disciples by personal teaching." Such a definition stresses "the intact transmission of authoritative written texts over generations, generally accompanied by personal teaching to ensure that the texts would be correctly understood so that their accurate reproduction and transmission could continue." These lineages of teaching were not fixed historical entities, however. Rather, a "school" in the latter sense represented a claim made by individuals or groups about their connections to forebears. The act of passing on the texts through personal teachings was key.[5]

[3] For more detail see my "Ch'ing Dynasty 'Schools' of Scholarship."

[4] Cahill, Parting at the Shore , pp. 135, 163.

[5] Sivin, "Copernicus in China," p. 96n. See also Sivin's "Foreword," in my Philosophy to Philology .

We are on firmer ground, however, when "schools" refer to specific geographical areas during particular periods of time. To speak, as Chinese scholars did, of the "Su-chou," "Yang-chou," or "Ch'ang-chou" schools during the Ch'ing dynasty does not completely obviate the dangers outlined above. Such groupings can nevertheless help us to evaluate intellectual phenomena below the macroregional level.

It is interesting, for example, that in a preliminary survey of Ch'ing academic life in Yang-chou and Ch'ang-chou, the Japanese scholar Otani[*] Toshio has pointed to the decisive influence of Hui-chou merchants from southeastern An-hui Province in Lower Yangtze social and cultural affairs. According to Otani[*] , such commercial links provided the social background for the transmission of Hui-chou scholarship first to Yang-chou (via Tai Chen, 1724-77) and then to Ch'ang-chou (via Tai's followers). Thus, the turn to Han Learning among Ch'ang-chou literati, which we will discuss further in chapter 4, can be traced in part to the influence of both the Su-chou school of Han Learning to the south and the Yang-chou school to the north.[6]

Although it may be true that Ch'ang-chou's place in the Hah Learning movement may have been derivative, such a perspective fails to explain the origins of the Ch'ang-chou New Text school, which neither Su-chou nor Yang-chou (or even Hui-chou) currents of thought ever duplicated. In fact, the commitment of Yang-chou families to Old Text traditions and of Ch'ang-chou families to New Text studies indicate that considerable tension and variation existed among Lower Yangtze schools of scholarship in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Accordingly, we shall have to search for the origins of New Text Confucianism in the schools of scholarship championed by Confucian literati in Ch'ang-chou itself.[7]

The problem of what constitutes an intellectual school in China is central to our concerns. In our efforts to interweave the eighteenth-century reemergence of New Text Confucianism with the social history of Ch'ang-chou Prefecture—one of the key economic and cultural centers in the Lower Yangtze macroregion during the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties—we shall explore local differences in intellectual content and style. Three questions will be in the background of our inquiry: (1) What role did late-Ming intellectual movements in Wu-hsi County play

[6] Otani[*] , "Yoshu[*] Joshu[*] gakujutsu ko[*] ," pp. 319-21. Hsu K'o, in his Ch'ing-pai lei-ch'ao , vol. 69, pp. 19-20, had earlier also noted the links between the "Ch'ang-chou school" and the "Hui-chou school."

[7] Eiman, "Ch'ing Dynasty 'Schools' of Scholarship," pp. 12-15.

in the intellectual life of Ch'ang-chou Prefecture? (2) Why during the Ch'ing dynasty did the mantle of scholarly leadership in Ch'ang-chou pass from Wu-hsi to scholars associated with the Chuang and Liu lineages in the prefectural capital? (3) What similarities and differences do we note between late-Ming currents in Ch'ang-chou and the rise of the New Text school there? Such questions reflect the local flavor that intellectual life could develop at prefectural and county levels within the larger academic community of the Lower Yangtze.

Lineages and Schools of Scholarship

The tendency to concentrate on individuals in the development of Confucianism has obscured the important roles played by family and lineage in the practice of Confucian social and political values. Historians cannot isolate Chinese literati from their social setting. Nor can intellectual historians afford to neglect the complex machinery of lineage communities in Chinese society.[8] Confucian scholars did not construct a vision of their political culture ex nihilo. Their mentalities were imbedded in larger social structures premised on the centrality of kinship ties. The influence of large kinship groups in traditional Chinese society should not he overexaggerated, yet at the same time we would do well to bear in mind that in the day-to-day affairs of local gentry, the Confucian elite was frequently defined by kinship relations; cultural resources were focused on the formation and maintenance of lineages.

The Huis in Su-Chou

The Chuangs and Lius in Ch'ang-chou were not the only lineages whose scholarly achievements gained national prominence. The scholarly traditions of the Hui lineage were intimately tied to the emergence of Han Learning in Su-chou during the eighteenth century. Hui Tung (1697-1758) built upon the teachings of his great-grandfather Hui Yu-sheng (d. ca. 1678) and grandfather Hui Chou-t'i (fl. ca. 1691), which had been transmitted to him by his distinguished father, Hui Shih-ch'i (1671-1741). Su-chou Han Learning traditions show us how teachings, once the cultural property of a particular line within a

[8] Twitchett, "A Critique," pp. 33-34.

lineage, passed into the public domain. Keeping Confucian teachings within the family line, and thus within the lineage, was a typical political strategy designed to maintain the success of a descent group in the empire-wide civil service examinations. State examinations were based solely on classical studies, so they were frequently pursued within a "lineage of teachings" based on kinship organizations. Such teachings were preserved to further the interests of the lineage in local society and in the civil service.

The Hah Learning of the Huis demonstrates, however, that there was a tension between public prestige and private traditions. The exclusivity of lineage schools, for instance, could be tempered by a local tradition of scholarship. This could then enhance lineage prestige when its scholarly tradition entered the public domain. Consequently, lineage academies could fulfill exclusive and inclusive roles, depending on the cultural strategies of a particular lineage vis-à-vis surrounding society. Accordingly, both Han Learning in Su-chou and New Text Confucianism in Ch'ang-chou represented at different times the exclusive teachings of a particular lineage and the inclusive doctrines of a school of learning.

Originally from Shensi Province in the northwest, the Huis began their flight south when the Wei River valley—the heartland of Chinese civilization during the Han and Tang dynasties—fell to Khitan invaders by 947. During the Ming dynasty the Huis settled in Su-chou, but they did not come to prominence there until the late Ming and early Ch'ing, when the scholarly achievements of Hui Wan-fang, Hui Tung's great-great-grandfather, were widely recognized.[9]

Hui Chou-t'i was the first in the Hui lineage to pass the highest level chin-shin (presented literatus) examinations. It was his subsequent appointment to the prestigious Hanlin Academy (Han-lin yuan ) that moved the Huis into national prominence. His son Shih-ch'i passed the provincial examinations in 1708, and in 1709 Shih-ch'i duplicated his father's achievement by passing the chin-shih examination in Peking with high honors. The Hui lineage had thus placed its sons from two consecutive generations in the Hanlin Academy, which was the starting point for guaranteed official power and influence. The "Han Learning" associated with Hui Tung in Su-chou derived from scholarly traditions

[9] On the Hui lineage see Hui-shih ssu-shih ch'uan-ching t'u-ts'e . See also Yang Ch'ao-tseng (then governor-general in Su-chou), "Chi-lu," pp. la-7b. Cf. Dardess, "Cheng Communal Family."

and cultural resources built up over four generations of his immediate family,[10]

Hui Tung drew on traditions of "ancient learning" (ku-hsueh ) and "classical techniques" (ching-shu ) transmitted within his lineage to articulate a scholarly position predicated on the superiority of Han dynasty sources over T'ang, Sung, and Ming Confucian writings. Rather than study the Four Books (a Sung-Yuan concoction associated with Sung Learning), the Huis stressed the Five Classics of antiquity in their efforts to reconstruct Han Learning. The Huis' financial success and intellectual prominence in the eighteenth century permitted Hui Tung the luxury of study and research to build a "school of learning" in Su-chou.

Despite the exclusivity of lineage schools, the success of the Hui family in influencing Su-chou scholarship illustrates that lineage traditions possessed important complementary elements of private advantage and public influence. The organizational rationale for the Su-chou "school of Han Learning" rested on teachings transmitted by the Huis to scholars and students outside of the Hui lineage who resided or studied in Su-chou. Ch'ien Ta-hsin and Wang Ming-sheng, both native sons of nearby Chia-ting, for example, were caught up in the wave of Han Learning in the 1750s when they were studying in Su-chou. They became influential k'ao-cheng scholars during the heyday of Han Learning in the 1780s and 1790s.

Hui Tung remained a private scholar throughout his life and worked in his Su-chou studio famous for its library. This independent scholarly tradition, financed by the Huis' earlier successes, would diverge from official standards and ultimately add to critical k'ao-cheng styles of classical inquiry. Hui Tung's career also suggests that during the early decades of the Ch'ien-lung Emperor's reign there was a chasm between private Han Learning and public examination studies, which remained predicated on mastery of Sung Learning.[11]

[10] See Lu Chien's "Hsu" (Preface) to Hui Tung's Chou-i shu , p. 1b. See Bourdieu, Theory of Practice, pp. 171-83, for a discussion of "symbolic capital."

[11] Hummel et al., Eminent Chinese , pp. 138, 357-58. Cf. my discussion of "professionalized scholars" in Philosophy to Philology , pp. 133-34. Before the abolition of the Confucian examination system in 1905, the Five Classics and Four Books were the backbone of the education system. The Five Classics were the Change, Documents, Poetry, Rites, and the Springand Autumn Annals . A Music Classic had been lost in the classical period. The Four Books were the Analects, the Mencius , the "Great Learning," and the "Doctrine of the Mean."

The Wangs and Lius in Yang-Chou

In Yang-chou the Wang and Liu lineages, much like the Huis in Su-chou, carried on traditions of Han Learning. K'ao-cheng studies had become important in Yang-chou during the eighteenth century initially through the efforts of Wang Mao-hung (1688-1741). The latter applied evidential research techniques to the study of Chu Hsi's (1130-1200) life and scholarship. Wang compiled a detailed chronological biography (nien-p'u ) of Chu Hsi that cut through the hagiography that secured Chu's status as the fountain of Neo-Confucian moral philosophy. Later scholars in Yang-chou traced their studies back to Wang Mao-hung, but few actually received or continued his teachings.[12]

Yang-chou scholars were strongly influenced by Hui Tung's Su-chou school of Han Learning. Chiang Fan, for instance, studied in Su-chou under some of Hui Tung's direct disciples and was frequently sponsored by his townsman Juan Yuan, one of the great patrons of Han Learning in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Chiang Fan, with Juan's support, subsequently compiled a controversial but authoritative genealogy of Hah Learning masters entitled Kuo-ch'ao Han-hsueh shih-ch'eng chi.[13]

The more formative scholarly influence in Yang-chou, however, was the polymath Tai Chen and his critical approach to scholarship. Although himself a member of the southeast An-hui (Wan-nan ) school centering on Hui-chou Prefecture, Tai lived and taught in Yang-chou from 1756 until 1762. Initially, Tai taught in the home of Wang An-kuo, who had the foresight to have his son Wang Nien-sun receive instruction from one of the future giants of the k'ao-cheng movement. Wang Nien-sun acquired his training in ancient phonology (ku-yin ) and etymology (ku-hsun ) from Tai Chen, which he then transmitted to his celebrated son Wang Yin-chih (1766-1834). Nien-sun and Yin-chih became two of the most influential Hah Learning scholars during the Ch'ing dynasty, and therefore brought honor and prestige to their lineage in Yang-chou.[14]

The scientific cast to Tai Chen's k'ao-cheng studies was the product of Hui-chou traditions of learning. Since Mei Wen-ting (1633-1721) and the Jesuit introduction of Western science to Chinese intellectuals,

[12] Liang, "Chin-tai hsueh-feng chih ti-li te fen-pu," pp. 20-21.

[13] Kondo, " O[*] Chu[*] to Kokusho Jurinden ko[*] ," pp. 64-69.

[14] Cf. my "Ch'ing Dynasty 'Schools' of Scholarship," pp. 12-14.

Hui-chou learning had stressed the reconstruction of classical astronomy, mathematics, and calendrical science. Going beyond Han Learning scholars (who they thought placed undue emphasis on Later Han dynasty sources as the basis for textual criticism and verification), Tai Chen and his followers developed a more impartial approach to Han materials and attempted to verify knowledge in a more formal manner. A distinguished textual scholar in his own right, Wang Chung described the Yang-chou intellectual scene: "At this time [ca. 1765], ancient learning [ku-hsueh] was popular [in Yang-chou]. Hui Tung of Yuan-ho [in Su-chou] and Tai Chen of Hsiu-ning [in An-hull were admired by everyone"[15] Such scholarly currents also penetrated the Liu lineage in Yang-chou, where learned members like the Wangs began to specialize in Han Learning. Liu Wen-ch'i (1789-1865), in particular, initiated research on the Tso Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals, which became the pet cultural project of his line into the twentieth century, when Liu Shih-p'ei (1884-1919) gave up radical politics to devote himself to the scholarly traditions of his lineage.

By concentrating on the Old Text interpretation of the Annals based on the Tso chuan, the Lius in Yang-chou placed themselves in direct opposition to New Text views emerging in Ch'ang-chou. Liu Shih-p'ei's father, Liu Kuei-tseng, and grandfather Liu Yü-sung had continued the task of reconstructing the Tso chuan into the last half of the nineteenth century. They stressed the more orthodox traditions of Hah Learning that upheld the priority of Later Han Confucians for interpreting the classical legacy.[16]

The scholarly disputations between Liu Shih-p'ei (Old Text) and K'ang Yu-wei (1858-1927) (New Text) in the twentieth century became famous. The roots of this confrontation between the Lius in Yang-chou (Old Text) and the Chuangs and Lius in Ch'ang-chou (New Text) have not been generally recognized. Liu Wen-ch'i had set the course in 1838 for this confrontation with his Tso chuan chiu-shu k'ao-cheng (Evidential analysis of ancient annotations of the Tso Commentary ), in which he tried to reconstruct the Later Han dynasty (hence, Old Text) appearance of the Tso chuan. In his 1805 study entitled Tso-shih ch'un-ch'iu k'ao-cheng (Evidential analysis of Master Tso's Spring and Autumn Annals ), Liu Feng-lu presented the Ch'ang-chou school's New Text position on the Tso chuan (see chapter 7).

[15] Wang Chung, Shu-hsueh, wai-p'ien (outer chapters), l.9b.

[16] See Chang Po-ying's "Hsu," (Preface), p. la; and Hummel et al., Eminent Chinese , pp. 534-36.

The Lius' research project—carried on by Liu Wen-ch'i's son, Liu Yü-sung, but never completely finished even in the twentieth century— sought to dismiss post-Han interpretations, principally those of Tu Yü (222-284). They argued that these interpretations had falsely articulated "precedents" (li ) in the Annals on the basis of forced inferences from the Tso chuan. Liu Wen-ch'i's research was mainstream Han Learning and drew on the legacy of Hui Tung and on the contributions of Chiao Hsun, who was Tai Chen's disciple in Yang-chou.[17]

In addition, Liu Wen-ch'i came out in favor of his maternal uncle Ling Shu's Kung-yang li-shu and Ch'en Li's Kung-yang i-shu. Both works were Old Text-based reconstructions of the Kung-yang chuan as a historical source that complemented the Tso chuan. Ling Shu and Ch'eh Li saw historical value in the Kung-yang Commentary but were suspicious of the "empty speculations" (k'ung-yen ) associated with the Kung-yang tradition. They attributed such speculations to the unfortunate millennial visions Ho Hsiu (129-182) had read into the text during the Later Han dynasty.[18]

At first sight, the opposition between the Lius in Yang-chou and Chuangs in Ch'ang-chou over the correct commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals seems mainly intellectual, with few political overtones. In fact, however, the debate represented the clash of opinion between a Yang-chou lineage devoted to apolitical Han Learning scholarship and a lineage in Ch'ang-chou bent on preparing its sons for the political arena. Unlike the Huis and Wangs, the Chuangs would use New Text studies to voice their concern over the rising influence of apolitical k'ao-cheng during the last decades of the Ch'ien-lung Emperor's reign, when the dynasty was beset with what they considered unprecedented corruption and political instability. We shall discuss the Chuangs' use of New Text studies in later chapters.

The Fangs and Yaos in T'ung-Ch'eng

In addition to Su-chou and Yang-chou, the city of T'ung-ch'eng in northern An-hui Province (known as Wan-pei), also featured a distinctive school of scholarship transmitted by prominent gentry lineages, the

[17] Liu Wen-ch'i, Ch'ing-hsi chiu-wu wen-chi , 3.9b.

[18] Ibid. See also his "Hsu" (Preface) to Ch'en Li's Chü-hsi tsa-chu , pp. la-2a; and Ling Shu's Kung-yang li-shu , 862.15b. For a discussion, see Yang Hsiang-k'uei, "Ch'ing-tai te chin-wen ching-hsueh," 190-96. However, Ch'en Li, as we will see in chapter 7, was also influenced by Liu Feng-lu's New Text scholarship.

Fangs and the Yaos, for much of the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties. In contrast to their southern An-hui (that is, Hui-chou) contemporaries, members of the T'ung-ch'eng school of learning were famous for their influence in promoting the ancient-style prose from the T'ang and S'ung dynasties, called ku-wen writing, and for their partisan support of Sung dynasty Confucian moral philosophy in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.[19]

Through family traditions in literature and examination studies members of the Fang and Yao lineages provided the organizational framework and intellectual resources for articulating and passing on the orthodox teachings of the Ch'eng-Chu persuasion in T'ung-ch'eng. During the Ch'ing period, for example, fourteen Yaos and twenty-one Fangs had mastered the orthodox Chu Hsi teachings well enough to achieve chin-shih status. Fang lineage traditions extended back to the Ming dynasty and Fang I-chih (1611-71) among others. But later followers such as Fang Tung-shu (1772-1851) referred to Fang Pao (1668-1749) as the progenitor of an orthodox defense of Chu Hsi teachings.

Having endured, with his family, the heavy hand of the Manchu state, Fang Pao served during his last years as a spokesman for state orthodoxy. He defended the authenticity of the long-impugned Old Text Rituals of Chou (Chou-li ), for example, and ridiculed those who dared label the Han Confucian Liu Hsin (45 B.C.-A.D. 23) a forger of the Chou-li and other Old Text Classics, a major issue in the Old Text-New Text controversy. Seeking to convert heterodox scholars (usually those who followed Han Learning) to Sung Learning, Fang Pao went so far as to claim on the occasion of the death of Li Kung's (1659-1733) eldest son that the misfortune was brought on by Li's heterodoxy and his irresponsible attacks on Chu Hsi.

In his scholarship on the Spring and Autumn Annals, for example, Fang Pao directly linked the literary heritage of ancient-style prose to the world-ordering commitments Confucius had enunciated in the Annals. Fang equated the "models and rules" (i-fa ) that would be the hallmark of the T'ung-ch'eng school's orthodox position with the historical style of the Annals. The latter was encoded in literary forms of "praise and blame," which Fang Pao contended were best elaborated and developed by the Tso chuan. The ku-wen prose tradition revived by

[19] Hsu K'o, Ch'ing-pai lei-ch'ao, vol. 69, p. 7; vol. 70, pp. 30-34.

Han Yü in the eighth century had, according to Fang, recaptured the moral power of ancient literary forms.[20]

In the late eighteenth century—in part because Fang Pao and his family were implicated in the 1711 literary inquisition and were thus uprooted from their ancestral home—the Yao lineage in T'ung-ch'eng assumed leadership of "orthodox" Confucianism through the influence of Yao Nai (1732-1815) and Yao Ying (1785-1853). Yao Nai sought to counter the compositional principles used in parallel-prose writing (p'ien-t'i-wen ), favored by Han Learning scholars in Yang-chou and elsewhere, by championing "models and rules" preferred by writers of ancient-style prose. Yao's efforts were supported by the Yang-hu school of ancient prose in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture, with whom the T'ung-ch'eng school developed a literary rivalry. In addition, Yao Nai defended Sung Learning orthodoxy against what he considered the wayward classical studies produced by k'ao-cheng scholars.[21]

Likewise, Yao Ying, along with Fang Tung-shu and others associated with the T'ung-ch'eng school, felt the Han Learning movement threatened the Sung Learning orthodoxy in official life and thus public morality in private life as well. They therefore defended in passionate terms the state-sanctioned teachings of the Sung Ch'eng-Chu school. Yao Ying, for example, wrote:

In antiquity, scholars studied the Way to rectify their minds. Today, scholars study literary composition [wen ] to damage their minds. . ..In antiquity, scholars were intent [on following] the Way. Thus they relied on loyalty and trustworthiness to study filial piety. They studied [such ideals] in order to serve their ruler, respect their elders, and clarify rituals. Literary composition was therefore mastered in the process of study. Today, scholars are intent [only on mastering] literary composition. They seek only for fame and fortune in their studies. Thus, their literary compositions are empty.

From such lineage alignments we see that the Han Learning-Sung Learning debate was also carried on in literary fields. The predilection of Han Learning advocates for Han dynasty "parallel prose" versus the

[20] Fang Pao chi, pp. 16-21, 58-59; and Hummel et al., Eminent Chinese , pp. 235-40. Fang Pao and his family were initially imprisoned and then later served either as nominal slaves to Manchu bannermen in Peking or were exiled to the northeast. See also Aoki, Shindai bungaku hyoronshi[*] , pp. 518-26; Beattie, Land and Lineage in China , p. 51; and Ebrey, "Types of Lineages in Ch'ing China."

[21] See Yao Nai's Ku-wen tz'u lei-tsuan ; and Yao's 1796 "Hsu" (Preface), to his Hsi-pao-hsuan chiu-ching shuo , pp. 1a-1b. See also Yao Ying, Tung-ming wen-chi , 3.2b. See also Guy, The Emperor's Four Treasuries , pp. 140-56.

preference for T'ang-Sung "ancient-style prose" among Sung Learning scholars meant that for each side proper composition required forms of expression appropriate for the task of precise scholarship (Han Learning parallel prose) or moral-philosophical articulation (Sung Learning ancient-style prose). Lineages such as the Huis, Wangs, and Lius in Su-chou and Yang-chou thus stressed in their private schools cultural and linguistic training in writing techniques acceptable for Han Learning.

Similarly, the Fangs and Yaos in T'ung-ch'eng made ancient-style prose the vehicle for their moral-philosophical commitments. T'ung-ch'eng schoolmen saw ancient prose and moral values as inseparable and tried to effect a synthesis of moral philosophy and literary style by equating the content of Sung Learning—that is, Neo-Confucianism— with ancient-style prose as the proper vehicle for its expression.[22] Moreover, the Fangs and Yaos attacked the Han Learning emanating from Su-chou and Yang-chou as heterodox and morally bankrupt. Yao Nao in particular developed a large following in Nan-ching in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries while teaching at the prestigious Chung-shan Academy. Despite his Sung Learning priorities, however, Yao Nai, as well as Yao Ying and Fang Tung-sbu, had to admit the importance of k'ao-cheng research techniques. In his 1798 preface to Hsieh Ch'i-k'un's (1737-1802) widely acclaimed Hsiao-hsueh k'ao (Critique of classical philology), for example, Yao Nai appealed for a balance between Han Learning and Sung Learning in a proper Confucian education,[23]

Similar alignments occurred in Ch'ang-chou, where scholars associated with the Yang-hu school (named after a county) of ancient-style prose and the Ch'ang-chou school of tz'u (lyric) poetry also navigated the literary and philosophic currents separating Han Learning from Sung Learning. In both classical scholarship and traditional Chinese prose and poetry, Ch'ang-chou literati tended to be less favorably disposed to Hah Learning than their peers in Su-chou and Yang-chou.

This brief sample of the cultural resources of kinship groups in late imperial China demonstrates that kinship is a unique vantage point from which to interpret the social and political dimensions in Yangtze Delta intellectual life. Before turning in chapter 2 to more detailed discussion of the Chuang and Liu lineages in Ch'ang-chou, we shall first

[22] Yao Ying, Tung-ming wen-chi, 2.14a-14b. See Edwards, "A Classified Guide," pp. 770-88; Aoki, Shindai bungaku hyoronshi[*] , pp. 526-33; and Pollard, A Chinese Look at Literature , pp. 140-57.

[23] Yao Nai, Hsi-pao-hsuan ch'üan-chi , 4.22a-23b.

explore the social, political, and cultural factors that enabled kinship organizations in the Yangtze Delta to achieve prominence in local society and national affairs.[24]

Linages in Late Imperial "China

Individuals did not speak as individuals in Confucian China. Western historians assume the autonomy of the individual from his descent group, so it is difficult for them to understand that Confucian literati spoke as members of kinship organizations. A lineage was not an abstract social grouping. For its members it was, according to James L. Watson, "an integral part of their personal identities." Confucian moral theory added to, and was channeled by, the politics of lineage formation.[25]

It is now generally recognized that there was no uniform process of lineage formation in late imperial society. The Chuangs and the Lius in late imperial China constituted a territorial entity as well as a descent group. Both geographical and historical factors added variations to highly localized forms of kinship ties. Late imperial society was structured by political and economic forces that made descent an ideological system as well as a social fact. Elite lineages in traditional society were not passive reflections of, but rather dynamic contributors to, the political, economic, and social order.[26]

Lineages dominant in particular regions played an essential organizational role in late imperial Chinese society. With corporate property, ancestral halls, and written genealogies, they were largely a product of gentry descent-group strategies dating back to the Sung dynasty. Their social importance and increased numbers in the sixteenth century coincided with the weakening of the Ming imperial state in local society between 1400 and 1600. Corporate lineages with charitable estates occurred more frequently among gentry in local society as the forces of rural commercialization and market specialization changed the face of

[24] Chia-ying Yeh Chao, "Ch'ang-chou School of Tz'u Criticism," pp. 151-88. I have limited mention of lineages to those given above to avoid being carried too far afield from the focus of my study.

[25] Maurice Freedman, Chinese Lineage and Society ; and James L. Watson, "Hereditary Tenancy," p. 176.

[26] For a discussion see Ruble S. Watson, "Creation of a Chinese Lineage," 95-99; Pasternak, "Role of the Frontier," 551ff; Baker, Chinese Family and Kinship ; Ahern, "Segmentation in Chinese Lineages," pp. 1-15; and Maurice Freedman, Chinese Society , pp. 339ff.

Lower Yangtze local society after 1400. Through a corporate estate, which united a set of component local lineages, higher-order lineages became an essential building block in local society.[27]

Gentry Society in the Late Ming

Serving as state servants and local leaders, gentry became part of the machinery established by the Hung-wu Emperor (r. 1368-98) in the late fourteenth century to control the countryside. The Ming li-chia tax system (li-chia is a village/family unit of 110 households), geared to a village commodity economy, represented a compromise between the state's efforts to consolidate imperial power while relying on agrarian communities for state income. Families in each village thus assumed social and fiscal responsibilities. Every civilian household was in effect located in a hierarchy of command that empowered local elites.[28]

But imperial institutions could not keep pace with the social and economic changes in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, which introduced new elements into agrarian society. China's population grew from approximately 65 to 150 million between 1400 and 1600, a phenomenon accompanied by significant changes in economic conditions. The court and its bureaucracy lost control of its land and labor resources. The Ming tax system, based on fourteenth-century assumptions regarding land, population, labor service, and tax registers, quickly became anachronistic.[29]

The amount of uncollected taxes increased as lands were deserted, government lands were illegally sold on the open market, and land trusteeships (kuei-chi ) were secretly established to take advantage of tax exemptions that favored government officials. As a consequence, even greater financial and labor service burdens were placed on taxable farm households. In the Lower Yangtze, the fraudulent registration of property under names of officials had become a pervasive practice by the late Ming. Su-chou, Hang-chou, and Ch'ang-chou prefectures were especially notorious in this regard.

[27] Twitchett, "Fan Clan's Charitable Estate," pp. 97-98; and Ebrey, "Development of Kin Group Organization," pp. 53-56. For late Ming social change, see Shigeta, "Origins and Structure of Gentry Rule," pp. 337-85. See also Wiens, "Changes in the Fiscal and Rural Control Systems," pp. 53-69; Eberhard, Social Mobility in Traditional China, pp. 31ff; and Dennerline, "New Hua Charitable Estate," p. 53.

[28] Ray Huang, Taxation and Governmental Finance , pp. 1-24; Huang Ch'ing-lien, "Li-chia System," pp. 103-155; Brook, "Ming Local Administration," pp. 29-37; and Wang Yuquan, "Ming Labor Service System," pp. 1-44.

[29] Huang Ch'ing-lien, "Li-chia System," pp. 120-45; and Wang Yuquan, "Ming Labor Service," pp. 24-25.

Exemptions for officials became the single greatest tax loophole. Poorer households renounced their financial independence and chose to subordinate their land to influential households with a tax-exempt status—further stratifying rural society. The tax quota in the Lower Yangtze gradually shifted from government, that is, "official," land to private, or "commoner," land.[30]

The increasing monetarization of the economy in the Lower Yangtze and elsewhere also crippled the li-chia system by making inevitable the commutation of labor services into cash levies. The tax collection and labor service machinery of the li-chia system became obsolete, while absentee landlords, rural-urban migration to the cities, and secret trusteeships through official tax exemptions all increased, shattering the myth of communal solidarity in the "village/family" tax system. In the end, the state lost any capacity to regulate the economy through the tax system.[31]

During the sixteenth century the Single-Whip tax reform (I-t'iao pien-fa ) represented the culmination of late Ming efforts to come to grips with the tax assessment crisis. This remarkable reform transferred the tax burden entirely to agricultural fields, thereby amalgamating and commuting many taxation categories. Taxes were equalized on the basis of both adult-male labor and land holdings, and in turn land and labor taxes were converted into a single payment in silver.[32]

As regional trade increased the economic functions (as opposed to political status), of market towns and dries enlarged. Market towns increased twofold between 1500 and 1800, and many village settlements in the Lower Yangtze Delta became local trading centers. The functions and activities essential to operating commercial townships within rural communities fell into the hands of local gentry. This devolution of political power from the magistrate to local gentry facilitated the dominance of the latter.[33]

[30] Wiens, "Changes," pp. 61-65; Huang, Taxation , pp. 154-62; and Wang Yuquan, "Ming Labor Service," pp. 16-21. See also Hamashima, Mindai Konan[*] noson[*] shakai no kenkyu[*] , pp. 215-61.

[31] Philip C. C. Huang, Peasant Economy in North China . See Wiens, "Lord and Peasant," 3-34; and Kawakatsu, Chugoku[*] hoken[*] kokka no shihai kozo [*] , pp. 440-45.

[32] Shigeta, Shindai shakai keizaishi kenkyu[*] , pp. 155-201; Ray Huang, Taxation , pp. 112-33; and Yamane, "Reforms in the Service Levy System," pp. 279-310. See also Wiens, "Cotton Textile Production in Early Modem China," pp. 515-34; and Mori, "Gentry in the Ming," pp. 31-38. On cotton, see Dietrich, "Cotton Culture in Early Modem China," pp. 130ff; Nishijima, "Early Chinese Cotton Industry," p. 27; and Tanaka, "Rural Handicraft in Jiangnan," pp. 81-100.

[33] Fang Xing "Economic Structure of Chinese Feudal Society," pp. 126-30; and Shih-chi Liu, "Some Reflections on Urbanization." See also Brook, "Ming Local Administration," pp. 2-3, and Brook "Merchant Network."

Larger market towns in Su-chou, Sung-chiang, and Ch'ang-chou prefectures became interlocked with rural markets in the surrounding counties. By the late Ming many Lower Yangtze market towns below the county level specialized in commerce and handicrafts. The extent to which rice land was replaced by commercial crops in the delta region can be seen in the remarkable rise of "specialized towns" (chuan-yeh shih-chen ), in which the cultivation and manufacture of cotton, for example, tended to become separate operations, with a concomitant division of labor. Local commodity production along Lake T'ai in the Yangtze Delta quickly shifted from traditional household handicrafts of the early Ming into a kind of merchant or factory production.[34]

Silk, cotton, and rice markets emerged in specialized market towns, aided by the dense land and water routes of the Yangtze Delta. Such markets furthered the commercialization of the rural economy and spurred the cities' trading activities. Improved seeds, changing cropping patterns, and new cash crops (many from the New World) produced a doubling of grain yields as a complement to the extension of cultivated acreage between 1500 and 1800.

Commercialized handicraft production meant that changes in the rural economy would produce corresponding changes in the social order. The differentiation between urban enterprises and rural production households, which made peasant producers dependent on market forces and merchant middlemen, instituted financial relations that undercut Confucian social-moral obligations between landlord-officials and peasant-commoners in rural society.[35]

The mutual-assistance-and-support ideal of the Confucian moral economy, although unrealized, had been based on the protective (that is, favored) role played by the state and individual gentry-landlords in local society. But commercial activities drew more and more rural landlords and gentry into cities and towns, and the absentee landlordism that ensued meant diminished roles and moral prestige for gentry-landlords in village society. By 1600 market towns were populated in large part by merchants, hired laborers, and absentee gentry-landlords. Many were newcomers to late Ming urban life. Conspicuous consumption, the reduction of parochialism, and the growth of an urban culture, fre-

[34] Shih-chi Liu, "Some Reflections," pp. 14-19; Wiens, "Cotton Textile Production," pp. 519-22; and Fang Xing, "Economic Structure," pp. 124-31.

[35] Perkins, Agricultural Development in China , pp. 13-53; Ping-ti Ho, Population of China , p. 264; and Yeh-chien Wang, Land Taxation in Imperial China , p. 7.

quently described in late Ming novels, were produced by social conditions peculiar to the Lower Yangtze.[36]

Between 1400 and 1600 the complex triangular relationships among the imperial state, local gentry, and village peasants had been transformed. The retreat of the imperial bureaucracy from direct involvement in village affairs confirmed the dominance of the gentry-landlord elite in the late Ming and early Ch'ing periods, and the elite adjusted successfully to the transformation: under the umbrella of the centralized bureaucratic system, gentry-landlords in the Yangtze Delta diversified their interests into various forms of profiteering based on land rent and commercial enterprises; they also populated the state bureaucracy.

Lineage Organization

In the late Ming, therefore, those gentry who organized into powerful local lineages were able to fill the power vacuum in local affairs and to maintain political and economic control over rural society. Representing social groupings that operated between the family and the county-level political system, the lineage was uniquely situated to take advantage of late Ming economic opportunities as the increasingly anachronistic li-chia tax system gave way to the relative autonomy of villages and gentry rule. At times lineages were formed to manage the burden of imperial land taxes, At other times, they emerged to take advantage of economic opportunities for rural handicraft industry and increased agricultural commercialization.[37]

During the late Ming and Ch'ing dynasties, precisely because imperial administration was remote, powerful lineages in the Yangtze Delta (typically organized as localized kinship groups with high degrees of internal differentiation) influenced political and economic life in their area out of proportion to their actual numbers. This development did not represent an ideal of self-government. Partial decentralization, which ensured limited village autonomy, was one of the products of the struggle between Yangtze Delta gentry and imperial interests during the

[36] Wiens, "Cotton Textile Production," pp. 522-30; and Wiens, "Lord and Peasant," pp. 28-34. See also Kawakatsu, "Chugoku[*] kinsei toshi no shakai kozo[*] "; Fu I-ling, Ming-Ch'ing nung-ts'un ; and Yeh Hsien-en, Ming-Ch'ing Hui-chou hung-ts'un . The level of rural surplus remains unclear. The late Ming was a watershed in the development of the Chinese novel. See Hegel, Novel , pp. 67-130.

[37] Xu Yangjie, "Feudal Clan System," pp. 70-78. Cf. Freedman, Study of Chinese Society , pp. 338-39; and Freedman, Lineage Organization , pp. 114, 125, 138.

late Ming. Imperial power would blunt the literati parties and academies that threatened the absolutist state, but the social power of local gentry was not challenged. In the seventeenth century their local clout was redirected and redefined within powerful descent groups and affinal social and political strategies.[38]

During the Ming dynasty the breakdown of earlier sharp distinctions between landed wealth and merchant profits signaled a shift in gentry perceptions of acceptable financial resources and legitimated the involvement of degree holders and their lineages in local private economic affairs. Despite the anti-merchant biases voiced in official Confucian rhetoric, China did not have the rigid barriers between merchants and gentry that characterized early modern Europe or Tokugawa Japan (1600-1867). The Confucian order of gentry, peasants, artisans, and merchants, in that order, had long been a rhetorical ideal largely divorced from social reality. The Ch'ing dynasty "elite" was composed of both merchants and gentry.

Because the economic elite was closely linked to the gentry elite, success in one sphere frequently led to success in the other. Movement into the ranks of the literati from outside established gentry lineages took place through the accumulation of wealth derived from trade, not simply from land. A wealthy lineage relied on more than agriculture for its corporate investments. Trading, usury, and bureaucratic office each provided external sources of wealth that reinforced the local prestige of the lineage.

New corporate estates did not appear in every generation. First, a sizable profit had to be made by a prominent kinsman. Then each estate had to be managed and organized by a literate elite with the requisite legal, social, and political skills. Incorporation for the long-term management of wealth became routinized and lent form and structure to the process of amassing cultural prestige and political power for a lineage. Representing a collective structure of private interests, the corporate estate became the common denominator of elite lineage organizations and the bureaucratic rationalization of family-held concentrations of wealth.

Surpluses that quickly accumulated in the highly productive rice, sericulture, and cotton economies in the Yangtze Delta helped to orga-

[38] Beattie, Land and Lineage in China , pp. 86-87; and Xu Yangjie, "Feudal Clan System," pp. 30-33. See also Cole, "Shaohsing," pp. 112ff; Dennerline, "New Hua Charitable Estate," pp. 26-29; Freedman, Chinese Lineage and Society , pp. 20-21; Ruble S. Watson, Inequality Among Brothers , pp. 37-38; and Hsiao, Rural China , p. 263.

nize corporate property and to promote the development of large descent groups. Access to land-based or trade-oriented financial resources enabled a typical lineage to maintain its ancestral halls, pay for the upkeep of its private schools, and perform the expensive rituals associated with birth, death, and marriage appropriate to its high social standing.[39]

Also representing patriarchal authority, the corporate estate was legitimated through moral claims made in the name of the lineage. Alliances with affinal relations perpetuated lineage solidarity. To be recognized by state authorities, the estate had to be endowed by lineage members to relieve needy members and to help defray ritual expenses associated with burial ceremony and marriage protocol. As a philanthropic organization, the corporate estate gained certain tax advantages and reductions and was also protected from potentially disruptive property disputes.

Although the precise legal features granting political legitimacy to such corporate estates require more focused study, it is clear that such lineage strategies mitigated the damages wrought by partible inheritance. Perhaps legally savvy elites within a well-placed lineage performed many functions for their brethren that are comparable to the evolution of legitimate fiduciary advice in modern legal efforts to maintain the wealth and prestige of elite American families. The quasi-fiduciary role of elite segments within powerful higher-order lineages meant that those closest to the sources of wealth that created the estate to begin with benefited the most from tax reductions and access to estate income.[40]

Despite its stress on kinship solidarity, then, a lineage was not an egalitarian institution that bestowed benefits or prestige equally on all its members. Those kin distinguished by wealth and genealogical connection to wealthy benefactors dominated the complex social and economic dimensions of corporate property. Descent groups were imbedded in a class-based social and political system and thus included people from every stratum of society. Members were not treated equally

[39] Twitchett, "A Critique," pp. 33, 37-38, 98; and Potter, "Land and Lineage ," p. 134. See also Freedman, Lineage Organization, pp. 53-54, 75; Ruble S. Watson, Inequality , pp. 4, 36-40, 53, 115, 168, 172, 174; Dennerline, "Marriage, Adoption, and Charity," pp. 201-202; Marcus, "American Family Dynasties," pp. 224-41; and Zurndorfer, "Local Lineages."

[40] Marcus, "American Family Dynasties," pp. 221-23; and Hu, Common Descent Group , pp. 22-26; the judicial functions of a lineage are discussed in detail on pp. 53-63.

because differential conditions of economic wealth and political power gave some segments more say in lineage financial and ritual affairs, regardless of kinship, seniority, or age.

Clearly, dominant lineages had many local advantages when compared to lesser agnatic kinship groups in traditional China. Because they monopolized ties with the world beyond the locality, members of wealthy segments within a higher-order lineage served as cultural, legal, political, and economic intermediaries for poorer members of their descent group.[41]

Lineages and Cultural Resources

Granted imperial legitimacy, the social and economic strength of a lineage quickly correlated with success in the civil service examination, which in turn correlated with dominant control of local cultural resources. Lineages required literate and highly placed leaders who moved easily in elite circles and could mediate with county, provincial, and national leaders on behalf of the kin group. Economic surpluses produced by wealthy lineages, particularly in the prosperous Yangtze Delta, gave members of the rich segments better access to a classical education—fairly ensuring success on state examinations. Such success led in turn to sources of political and economic power outside the lineage. Greater educational opportunities ensured that powerful members of a dominant lineage had more knowledge of and control over the management of their lineage affairs.[42]

In order for a lineage to succeed over the long term, it needed sufficient financial resources to pay for the protracted education of its bright young male members in archaic classical Chinese. Wealth was the key to passing the formidable civil service examinations for which all talented males prepared. Students who came from a family with a strong tradition of classical scholarship thus had inherent local advantages over sons of lesser families and lineages. It was clearly more difficult for the son of a peasant or artisan to compete on equal terms with males in a lineage that already had established itself as an "official-producing group."

[41] Twitchett, "A Critique," p. 38; Freedman, Chinese Lineage and Society , pp. 97-117; and Shang, Chung-kuo tzu-pen chu-i kuan-hsi fa-sheng , pp. 257ff. Cf. Dennerline, "New Hua Charitable Estate," pp. 19-70; and Dennerline, "Marriage, Adoption, and Charity," p. 204. See also Ruble S. Watson, Inequality, pp. 104, 117-2.5.

[42] Bourdieu and Passeron, Reproduction , pp. 71-102.

Education was not simply a marker of social status. Within a broader society of illiterates and those literate only in the vernacular, those who controlled the written word in classical texts had political advantages. Compilation of genealogies, preparation of deeds, and settlements for adoption contracts and mortgages required expertise and contacts that only the elite within a descent group could provide. A cultural pattern for social climbing and entry into gentry society was readily apparent for any ambitious family on its way up the social ladder in late imperial China.[43]

Lower Yangtze merchants also became known as patrons of classical scholarship, supporting schools and academies in Su-chou, Yang-chou, and Ch'ang-chou. The result was a merging of literati and merchant social strategies and cultural interests. In late imperial China merchants in the Lower Yangtze and elsewhere were in the forefront of cultural life. It is nearly impossible, for instance, to distinguish Han Learning literati from salt merchants in the academic world of Yang-chou during the Ch'ing dynasty. The success of merchants in local society— particularly in urban centers like Ch'ang-chou, Wu-hsi, and so forth— clearly points to the correlation between profits from trade and high social status. Classical scholarship flourished as a result of merchant patronage, and books were printed and collected in larger numbers than ever before.[44]

Possession of the proper linguistic tools and educational facilities for mastering Confucian political and moral discourse was perceived as the sine qua non for long-term lineage success and prestige. Success on the imperial examinations and subsequent office-holding conferred direct power and prestige on those most closely related to the graduate and the official. But the flow of local prestige could go further afield, following diverse agnatic routes within the lineage and among affines. Lesser members could identify with, and to some degree share in, the prestige of men of their lineage or of affines.[45]

Charitable schools (i-hsueh ) within lineages represented another example of the intermingling of charitable institutions, education, and philanthropy. Lineage-endowed schooling provided more opportunity

[43] Ping-ti Ho, Ladder of Success . Cf. Freedman, Lineage Organization , p. 56; and Rubie S. Watson, Inequality , p. 105, See also Hu, Common Descent Group , pp. 64-80.

[44] Ping-ti Ho, "Salt Merchants," pp. 130-68; and Okubo[*] , Min-Sh in jidai shoin no kenkyu[*] , pp. 221-361. See also Freedman, Lineage Organization , pp. 58-59, 128; and Peterson, Bitter Gourd , pp. 67-72.

[45] Bourdieu, Theory of Practice , pp. 159-97, esp. 165, 169-71.

for the advancement of lesser families in the lineage than would have been possible where lineages were not prominent. Corporate descent groups as a whole benefited from any degree-holding member of the lineage, no matter how humble in origins. Accordingly, the failure of families in a lineage to maintain their status as degree-holders for several generations could be offset by the academic success of other agnates or affines. The social mobility of lineages, when taken as a corporate whole, was thus distinct from that of individual families.

Lineage schools and academies (shu-yuan ) reserved for sons of merchants became jealously guarded private possessions whereby the local elite competed with each other for social, political, and academic ascendancy. The kinship groups described earlier in this chapter began in the late Ming to concentrate on classical scholarship as a corporate strategy. As a result, they were able to set aside lineage resources to underwrite the education of male students before they took the imperial examinations and to subsidize their classical scholars after they passed these same examinations. Lineages in the Lower Yangtze provinces were best able to make these expensive long-term cultural investments.[46]

Analysis of the systems of inheritance, marriage, affinity, and education, along with land tenure and political organization, shows that powerful ideological statements were being made through elite kinship institutions. One such statement is seen in the reemergence of New Text Confucianism in Ch'ang-chou Prefecture during the Ch'ing dynasty, which was closely tied to the lineage traditions of the Chuangs and their long-standing affinal relations with the Lius. The Chuangs and Lius were able to allocate lineage resources in such a way that their prestige as a "cultured" (wen-hua ) lineage endured for more than three centuries. Written genealogies show they were an urbanized local elite based on wealth, education, kinship, and marriage ties.[47]

Our inquiry into the Chuang and Liu lineages and their rise to prominence in Ch'ang-chou society during the Ming-Ch'ing transition period—that is, the seventeenth century—provides an interesting portrait of the cultural roles that higher-order lineages played in late impe-

[46] Twitchett, "Fan Clan's Charitable Estate," pp. 122-23, Rubie S. Watson, Inequality , pp. 7, 98, 175; Cohen, "Lineage Development," p. 11; Freedman, Lineage Organization , p. 54; and Rawski, Education and Popular Literacy , pp. 28-32, 85-88.

[47] Peterson, Bitter Gourd, pp. 25-35; and Otani[*] , "Yoshu [*] Joshu[*] gakujutsu ko[*] ," pp. 313-14, James Watson, "Chinese Kinship Reconsidered," p. 601; Marcus, "Fiduciary Role," p. 239.

rial local society. To conclude our account of the interaction between schools of learning and lineage organizations in the Yangtze Delta, we shall address the political climate within which lineages such as the Chuangs and Lius replaced associations such as the Tung-lin partisans as vehicles for gentry mobilization.

Lineages and the State

We normally assume that there existed an inverse correlation between the power of the state and the development of kinship groups. Certainly kinship solidarity within a lineage and potential rivalry among powerful lineages in local society were not entirely compatible with a central government. Officials, particularly the county magistrate, would often tolerate limited autonomy of kinship organizations as long as they did not directly challenge the authority of the central government in local society. Moreover, by joining with other lineages to form higher-order clans (based on real or fictional kinship), members of corporate descent groups could pressure provincial administration to protect their judicial autonomy and tax exemptions.[48]

It is interesting, however, that despite the state's isolated efforts to control recalcitrant lineages and clans, it encouraged the growth of kinship groups in local society. The famous Fan charitable estate, for example, owed its very existence from the Northern Sung on to state officials who arranged tax exemptions for their lands. Without the active support of the state, the Fan lineage, which was based on the financial resources of its tax-exempt charitable estate, would not have survived as long as it did.

The reason the state supported localized kinship groups is not difficult to understand. The Confucian persuasion, conceptualized as a social, historical, and political mentality organized around ancestor worship, encouraged kinship ties as the cultural basis for moral behavior. Kinship values of loyalty and filial piety were thought to redound to the state. Accordingly, the moral influence of a higher-order lineage as a building block in local society was thought beneficial to the

state.[49]

More important, however, local lineages were a strong force for sta-

[48] James L. Watson, "Chinese Kinship Reconsidered," p. 616. See also Hu, Common Descent Group , pp. 95-96, and Hsiao, Rural China , pp. 323-70.

[49] Twitchett, "Documents of Clan Administration," and "Fan Clan's Charitable Estate," p. 108. See also Freedman, Lineage Organization , pp. 64, 114, 138.

bilizing rural society below the county magistrate's jurisdiction and thus facilitated the work of local officials. The legal-moral principle of collective responsibility in local society, moreover, applied both to the family units in the li-chia organizational system and to lineage groups in rural China. For tax administration and local justice, we have seen that the influence of lineage organizations frequently complemented that of the state in promoting order in village communities. Lineages—like li-chia appointees—served as unofficial auxiliaries for the state at or below the county level.

Lineages consequently did not develop in antagonism to the imperial state but rather evolved as a result of the interaction between state policies and social economic forces at the local level. They represented one form of social organization (based on kinship) in the larger context of nonkinship-based forms of community solidarity. Elite interests in local society were directed through organizational forms the state could accept: corporate lineages. What is remarkable about these social developments is that they were authorized by the Confucian state.[50]

Factions in Sung-Ming Confucian Politics

The ideology of Chinese family and lineage solidarity—which placed primary emphasis on maintaining good relations with one's agnates and affines—was easily assimilated into the broader ideology of gentry society; it also served as a defense of its role as mediator between the state and commoners. During the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties the state had no ideological problems with the principle of descent as the primary means of local organization. Such tolerance sharply contrasted with the state's unceasing opposition to the principle of nonkinship alliance through gentry associations, best represented in seventeenth-century China by the demise of the partisans associated with the Tung-lin Academy in Wu-hsi County.

Representing a late Ming convergence of Confucian moral philosophy and political activism, the Tung-lin partisans at their apogee of national influence commanded the attention of Confucians all over the Ming empire. As a Ch'ang-chou-based political faction, however, the

[50] Hu, Common Descent Group , pp. 53-63. My interpretation of the auxiliary-to-the-state role of lineages suggests this was an unintended outgrowth of the collapse of the Ming tax system. For discussion, see Faure, Chinese Rural Society , pp. 12-13, 164-65, 178-79, where lineages appear as "the unintentional creation of official policies."

Tung-lin partisans, unlike kinship organizations, had few respectable precedents with which to justify their actions in a Confucian-cum-Legalist state system. In a much quoted phrase from the Analects, Confucius said: "I have heard that the gentleman does not show partiality." The often-cited "Great Plan" chapter of the Documents Classic also specified that political unity required the absence of factions (wu-tang),[51]

In Confucian political theory persons of equal or near-equal status who formed parties or factions (p'eng-tang) were typically criticized as seekers of personal profit and influence. Impartiality, was the classical ideal, and government officials followed prescribed avenues of loyal behavior based on hierarchical ties between ruler and subject. Those opposed to groups like the Tung-lin partisans were thus able to stand on the moral high ground of Confucian teaching when they accused the partisans of being devoted solely to their own profit and influence,[52]

But such literati associations had their own moral high ground. Confucians had distinguished between good and bad factions since the Sung dynasty. The statesman Fan Chung-yen (989-1052) argued: "If through friendship men should work together for the good of the state, what is the harm?" Shortly thereafter, in 1045, Ou-yang Hsiu sub-mitred a memorial to the emperor entitled "On Factions" (P'eng-tang lun ), which built on Fan Chung-yen's strategy of transforming factionalism into a mark of moral prestige. In order to rally support for reforms that first Fang Chung-yen and then he had advocated, and to bring supporters of the proposed reforms into the government, Ou-yang Hsiu affirmed the loyalty and public-mindedness of legitimate factions,[53]

Others were ambivalent about peer group collaboration in the form of parties or factions. A leader of more conservative gentry, Ssu-ma Kuang (1019-1086), thought factions were tinged with private interests, but he blamed their existence on the political climate produced by the ruler: "Therefore, if the imperial court has parties, then the ruler should blame himself and should not blame his groups of officials." Chu Hsi, the later voice of imperial orthodoxy, was somewhat less forgiving. In his view parties and factions were in essence "selfish" (ssu )

[51] Shang-sbu t'ung-chien , 24.0499; Lun-yü yin-re , 13/7/31; and Lau, trans., Confucius, p. 90. See Wakeman, "Price of Autonomy," 41ff, and Chu T'an, Ming-chi she-tang yen-chiu .

[52] Munro, "Concept of 'Interest,'" pp. 182-83.

[53] Ou-yang, Ou-yang Wen-chung kung chi , 3.22-23 (translated in de Bary et al., Sources of Chinese Tradition , pp. 391-92. See also James T. C. Liu, Ou-yang Hsiu , pp. 52-64; and Ono, "Torin[*] to ko[*] (ni)," Tohogakuho[*] 55 (1983): 307-15.

political entities that betrayed the "public" (kung ) Tao. Peer group associations were rejected on a priori theoretical grounds. According to Chu Hsi, they betrayed Confucian principles (li ) of government,[54]

Nevertheless, by the middle of the sixteenth century it was not unusual for several private academies in a particular region to form an organization and to hold regular meetings to discuss educational, cultural, and political issues. Such associations were possible only through the patronage of local officials and the participation of gentry and merchants from a relatively wide surrounding region. The halls of private academies organized into these associations became stopping points and crossroads for peripatetic Confucian scholars and officials. The growth of these independent associations of private academies during the sixteenth century was viewed by many officials as a threat to the established political order,[55]

Private academies, like lineages, developed into organizations that could unify local and private involvement in cultural and political affairs. They surpassed anything comparable at the time. The Tung-lin Academy, which reappeared during the seventeenth century, was at the apex of a loose association of groups, clubs, and parties. The academy declared openly what had been brewing for more than half a century: the emergence of political organizations based on the long-term covert proliferation of private academies,[56]

The Tung-lin partisans in Ch'ang-chou predictably affirmed Ou-yang Hsiu's view of factions, implying that their position was based on a uniformity of moral views, not on private interests. Ku Hsien-ch'eng (1550-1612), for instance, distinguished between "upright men" (cheng-jen ) and "voices of remonstrance" (ch'ing-i ), on the one hand, and those whose partisanship was based on selfish interests, on the other. Similarly, Kao P'an-lung (1562-1626), who assumed leadership of the Tung-lin Academy in Wu-hsi after Ku's death, affirmed in unequivocal terms the useful role literati associations could play in public affairs.

Their followers appealed to an ideal of a "public-spirited party" (kung-tang ) as the proper channel for literati involvement in national

[54] Ssu-ma Kuang, Tzu-chih t'ung-chien , vol. 9, pp. 7899-7900. See also Chu Hsi, Chu Wen-kung wen-chi, 12.4b, 12.8b.

[55] Meskill, "Academies and Politics," pp. 149-53.

[56] Ibid., pp. 153-63; and Meskill, Academies in Ming China , pp. 87-96. See also Ono, "Mimmatsu no kessha ni kan suru ichi kosatsu[*] (jo[*] and ge)," 45, no. 2:37-67; 45, no. 3:67-92.

politics. Unlike the "privately motivated parties" (ssu-tang ) of the past, they claimed to be seeking an alternative that would allow men of honor to join together for the common good.[57]

The Abortiveness of Late Ming Politics

For a brief period between approximately 1530 and 1630 Ming autocracy was at first quietly and then vocally threatened by elite reaction against "authoritarian Confucianism." In an era when Chinese emperors had abdicated their day-to-day involvement with affairs of state, the power vacuum created at the center was filled by contending eunuch and gentry-official factions. A devolution of local power in turn left the gentry firmly entrenched at home.

The collision course between gentry-organized private academies and central authority climaxed in the early seventeenth century, when the Tung-lin Academy in Wu-hsi joined with neighboring academies in Wu-chin and l-hsing. The resulting diffuse but still powerful Ch'ang-chou faction was able to influence imperial policy in Peking. Their power reaching a peak between 1621 and 1624, the Tung-lin partisans then suffered a series of reverses that coincided with the rise of the eunuch Wei Chung-hsien, who became the young T'ien-ch'i Emperor's (r. 1621-28) most intimate advisor. Despite their high place in the imperial court, the Tung-lin representatives were gradually undermined by Wei's faction at court and eventually dismissed from office.

The purge of Tung-lin partisans reached its apogee in the summer of 1625. Arrests and deaths by torture of Tung-lin leaders were accompanied by imperial denunciations of private academies as politically subversive organizations. Private academies throughout the empire were ordered destroyed. The halls of the Tung-lin Academy, partially destroyed in 1625, were completely torn down by imperial order in 1626. A special order was sent out from Peking to tear down all academies in Ch'ang-chou and Su-chou prefectures in particular because most were assumed to be part of the Tung-lin organizational network.

Although it was manipulated by crude politicians for their own purposes, the chief theoretical issue in 1625 was imperial prerogative versus the possibility of concerted and organized gentry involvement in politics. A century-old problem, the issue defined the threat posed by

[57] Hucker, "Tung-lin Movement," p. 143; and Ono, "Torin[*] to[*] ; ko[*] (ichi)," p. 589.

private academies and associations in light of the realities of political power within an autocratic imperial state. Wei Chung-hsien's crude purge of his Tung-lin opponents mirrored a fear widely held among more cultivated Confucians that it was wrong to establish separate political organizations for the advancement of personal interests.

All factionalism was impugned and repudiated with the officially sanctioned destruction of the Tung-lin Academy. The limits of what was politically permissible in Ming political life had been reached. Factions went against the public interests, which were represented ideally by the ruler. In the national political arena at least, late Ming efforts to strengthen gentry interests had failed.[58]

But Wei Chung-hsien's uses of terror could not rein in the political forces unleashed by the Tung-lin partisans. After Wei fell into disgrace in 1627 (he subsequently committed suicide) private academies and associations emerged in full force again. Factionalism likewise reared its divisive head in the political controversies that ripped apart the last reigns of the Ming dynasty. Among the most successful and best-organized group of literati were those associated with the Fu She (Return [to Antiquity] Society) movement, which revolved around Su-chou in the 1620s and 1630s. A formidable organization dedicated to supporting its members in the factional struggles that dominated late Ming politics, the Fu She represented the largest and most sophisticated political interest group ever organized within the imperial bureaucratic structure.

With the fall of the Ming dynasty first to peasant rebels and then to Manchu conquerors, the Fu She ceased to function and Ming factionalism disappeared. Both the Tung-lin partisans and their Fu She successors had sought ways to grant the gentry scholar-official a position of political prestige. But in the end their diffuse efforts failed. Confucians of the time attributed the demise of the Ming dynasty in part to imperial despotism but blamed the debilitating factionalism even more for failing to achieve a viable consensus for gentry involvement in national politics.[59]

If gentry forces had been able to influence the provincial and national

[58] Yang Ch'i, "Ming-mo Tung-lin tang yü Ch'ang-chou." See also Busch, "Tung-lin Academy." Primary sources are conveniently included in Tung-lin shih-mo and in Huang Tsung-hsi, Record of Ming Scholars , pp. 223-52. See the useful summary in Lin Li-yueh, "Ming-mo Tung-lin-p'ai te chi-ke cheng-chih kuan-nien," pp. 20-42. See also Goodrich et al., eds. Dictionary of Ming Biography , pp. 702-709. For a contemporary list of Tung-lin martyrs, see Chin Jih-sheng, Sung-t'ien lu-pi , pp. la-24a. Cf. Tung-lin pieh-sheng .

[59] Atwell, "From Education to Politics."

levels through legitimate factions such as the Tung-lin Academy or Fu She, what sort of political forces would have been released in Confucian political culture? Some scholars have speculated that the late Ming drive to reform the state "showed features strikingly similar to the trend against absolute monarchy and toward parliamentary rule in the West."[60]

Ming factionalism, however, was implicated as a chief culprit in the fall of the Ming house in 1644 and in the consequent triumph of the Manchus over a native Chinese dynasty clinging to life in south China until 1662. In fact, it is doubtful that the legitimacy of Confucian parties would have been vindicated even if the Tung-lin partisans had triumphed. Fearing peasant rebellion more than Manchu occupation, gentry recognized that their social and economic privileges depended on the political power of the state, which they quickly rejoined as officials. Vigorous Ch'ing emperors soon restored imperial initiative in political affairs, making what might have been a moot point until the turmoil of the nineteenth century.

Perhaps the most novel element in this ongoing conflict was not the extremes to which imperial autocracy would go to defend itself but rather the audacity of the gentry assault. With the increase of schools and academies during the late Ming, an enlarged educated class of elites emerged. The various reformist agendas of the thousands of Confucians affiliated with the Tung-lin Academy and the Fu She crossed a treacherous boundary within Ming authoritarian government.[61]

The fruitlessness of Ming activism should be seen in light of the increasing independence of the urban order within the imperial state. Criticism of the overbearing political authority of Ming imperial institutions carried over into the early decades of the Ch'ing dynasty. This is so even though the broader political consequences of Ming activism had been successfully aborted. The startling perceptiveness of such celebrated Ming loyalists as Huang Tsung-hsi and Ku Yen-wu— if understood in the context of the disintegration of the Ming state in the seventeenth century—marked major steps forward in Chinese perceptions of the intimate relation between Confucian institutions and autocratic state power.[62]

[60] Struve, "Continuity and Change," vol. 9, pt. 1.

[61] On the political aspects of local Tung-lin activities see Tanaka, "Popular Uprisings," pp. 181-83. See also Dennerline, "Hsu Tu," pp. 124-25, and Tsing Yuan, "Urban Riots," pp. 296, 309.

[62] Hou, "Lun Ming-Ch'ing chih chi te she-hui chieh-chi kuan-hsi ho ch'i-meng ssuch'ao te t'e-tien," 26-35. On the Tung-lin partisans, see Huang Tsung-hsi, Ming-Ju hsueh-an , pp. 613-42 (chüan 58), and Ku Ch'ing-mei, "Ch'ing-ch'u ching-shih chih hsueh yü Tung-lin hsueh-p'ai te kuan-hsi." Cf. de Bary, "Chinese Despotism." On Ku Yen-wu, see Goodrich, Literary Inquisition , pp. 75-76.

What exactly did the Tung-lin initiative represent? Did its failure in the seventeenth century mark the decisive divergence in historical trajectories between imperial China and revolutionary Europe? Did Tung-lin activism fail because the imperial state was overly autocratic or because the Confucian political style was suicidal? For a gentry-official to remonstrate with the Ming throne was tantamount to presenting one's head on a platter. Gentry solidarity was forbidden. Martyrdom was assured. Could gentry organizations like the Tung-lin have successfully carved out a political niche in Confucian political culture? These questions immediately come to mind as we evaluate the futility of late Ming politics against the backdrop of the powerful lineages of the Yangtze Delta.[63]

Lineages and Political Legitimacy