III. Kallimaghos

At this point the Alexandrian poets, in particular Theokritos and Kallimachos, become important. They demonstrate the struggle of Greek culture to come to terms with the new world and contribute to the self-understanding of the Greek elite. Greek poetry, of course, speaks to the Greeks within the Greek tradition. I shall not suggest that the Alexandrian poets found their audience in the mixed population of the countryside. They directed their poems to an audience that spoke Greek and felt Greek; and yet members of this audience had to administer the affairs of the king in his double role. In poems, therefore, which refer to the king and to ideas of kingship, we may find intersecting levels: the surface meaning in terms of Greek myth and Greek thought and the subsurface meaning in which the Greek narrative and the Greek forms reflect Egyptian ideas. This would show the audience that ideas that appeared to be foreign could still be understood in terms of the Greek mythical and poetical tradition. The poets were not Egyptianizing Greek thoughts, but Hellenizing those Egyptian ideas that had become common in the thinking of the court. Thus the influence of Egyptian ideas on Greek poetry stems paradoxically from the Greek efforts to Hellenize these Egyptian ideas. Here I must restrict myself to a few observations on Kallimachos.[125]

1. The Hymn to Delos

The inspiration Kallimachos received from the Egyptian ideology of kingship as it made itself felt at the court in Alexandria is clearest in his Hymn to Delos . But since this has been dealt with elsewhere, I can be very brief.[126] The learned reader easily savors the network of mainly Homeric

[125] Gf. T. Gelzer, "Kallimachos und das Zeremoniell des ptolemäischen Königs-hauses," in Aspekte der Kultursoziologie: Zum 60. Geburtstag von M. Rassem , ed. J. Stagl (Berlin, 1982), 13-30.

and Pindaric allusions, and he may even recognize the hymn as witty and thoroughly entertaining but at the same time as a serious realization of the Kallimachean program.[127] What may appear at first glance to be an exhibition of learnedness frequently reveals itself on a closer look to be a hint of the poetical intention. On a Greek level of understanding, the knowledgeable reader admires the novelty in which a traditional form reappears. But most readers will have difficulties in coming to terms with the long prophecy at the center of the poem (although prepared by other prophecies, to be sure), in which Apollo predicts the coming of Philadelphos and raises him to his own level.

At this point, the reader should observe the signs by which the poet indicates that an Egyptian side is involved too.[128] For example, Apollo is born when the Delian river Inopos is swollen with the waters of the Nile flood.[129] In Egyptian myth, Horus is born at the occurrence of the Nile flood and he hides on a floating island. In partial contrast, Delos was floating before the birth and finds its permanent place after the birth. In Apollo's prophecy of the future Ptolemaios, the king is the ruler of the "two continents [

[127] This, of course, does not imply that Kallimachos invented his program and then sat down to write his poems accordingly; nor should Kallimachos' remarks on his own poetry be reduced to a mere post factum defense (as G. O. Hutchinson does: Hellenistic Poetry [Oxford, 1988], 83). His poetical theory most likely developed as he wrote his poetry, and in this sense I speak of the fourth Hymn as a realization of his program (see Bing, Muse , chap. 3). Admittedly, the word "program" is unfortunate, but in view of the modern discussions, it is better to keep the term. See also Hutchinson, 77, against the "need to see . . . an articulated 'programme', which the works were consciously written to fulfil." He adds: "It may be doubted whether Callimachus had any 'programme' of that kind."

[128] For all we know, the Erigone by Eratosthenes was another example of a Hellenistic poem meant to be read on two levels, on a Greek and an "Egyptian" one, although the actual audience was Greek. See R. Merkelbach, "Die Erigone des Eratosthenes," in Miscellanea di studi Alessandrini in memoria di A. Rostagni (Turin, 1963), 469-526.

[129] Kall. H. to Delos 205ff.; L. Koenen, "Adaption," 175f.; Bing, Muse , 136f.; Mineur, Hymn to Delos , 186.

[130] For this concept see sections II.1.a and b (with n. 75) and lI.1.c (2) and (4).

tries.[130] Moreover, the pharaoh "conquers what the sun encircles." King Echnaton's real dominion is described as "the South and the North, the East and West and the islands in the middle of the sea"; it reaches "as far as the sun shines."[131] Is this parallel accidental? Probably in the sense that the passage on Echnaton expresses widely held Egyptian beliefs and Kallimachos need not to have known this specific passage; but hardly, if we refer to these broad Egyptian beliefs. The passage in Kallimachos' hymn goes on to predict Philadelphos' joint fight with Apollo (

). Apollo will destroy the Celts attacking Delphi, and Philadelphos will burn a troop of Celts on an island in the Nile. These mercenaries had fought in his service but were now accused of a mutiny.[132] They are characterized as wearing "shameless girdles" (

). Apollo will destroy the Celts attacking Delphi, and Philadelphos will burn a troop of Celts on an island in the Nile. These mercenaries had fought in his service but were now accused of a mutiny.[132] They are characterized as wearing "shameless girdles" ( , 183). The girdle fits the dress of the Celts, and yet it may be borne in mind that, in The Oracle of the Potter ,

, 183). The girdle fits the dress of the Celts, and yet it may be borne in mind that, in The Oracle of the Potter ,  is used as technical term for the Typhonians, the evildoers, the enemies of the gods and the king. This prophecy predicts the perfect pharaoh sent by the gods, who will come after an evil time and renew the country as well as the cosmic order. Such prophecies have a long pharaonic tradition from which specifically the term "wearer of the girdle" was inherited.[133] The extant versions of The Oracle of the Potter go back to an original composed, I believe, about 116 BC , but Kallimachos seems to have known a much older version. In his time, or in his mouth, the oracle favors the Greeks; around 116 BCThe Oracle of the Potter was anti-Greek; and in 115/117 AD , another prophecy featuring

is used as technical term for the Typhonians, the evildoers, the enemies of the gods and the king. This prophecy predicts the perfect pharaoh sent by the gods, who will come after an evil time and renew the country as well as the cosmic order. Such prophecies have a long pharaonic tradition from which specifically the term "wearer of the girdle" was inherited.[133] The extant versions of The Oracle of the Potter go back to an original composed, I believe, about 116 BC , but Kallimachos seems to have known a much older version. In his time, or in his mouth, the oracle favors the Greeks; around 116 BCThe Oracle of the Potter was anti-Greek; and in 115/117 AD , another prophecy featuring  is directed against the Jews and

is directed against the Jews and

[131] G. Davies, The Rock Tombs of El Amarna (London, 1906 3:31f.; M. Sandman, Texts from the Time of Akhenaten , Bibl. Aeg. 8 (Brussels, 1938), 6-10; J. Assmann, Ägyptische Hymhen und Gebete (Zurich and Munich, 1975), 224; for more see Koenen, "Adaption," 186-187 with nn. 119, 120.

[133] L. Koenen, "Manichaean Apocalypticism at the Crossroads of Iranian, Egyptian, Jewish, and Christian Thought," in Codex Manichaicus Coloniensis: Atti del simposio Internazionale, Rende-Amantea, Sett. 1984 , ed. L. Cirillo (Cosenza, 1986), 285-332, esp. 328-330 (on the "wearers of the girdle" and its occurrence in the Deir "Alla inscription, a Canaanite prophecy from 700 BC ).

apparently encourages the Greco-Egyptian population of the countryside.[134]

In view of this, it seems to me that Kallimachos not only understood crucial elements of the Egyptian ideology of kingship but also made poetic use of a prophecy propagating these ideas. He places Greek myths in an artful and witty arrangement of complementary or contrasting images in order to express the Egyptian ideology of kingship as it was accepted and propagated by the court. He made the ideology acceptable by putting the Egyptian prophecy and its ideology into the web of allusions to old Greek poetry.

On one level, then, the Hymn to Delos is an exemplary poem, an embodiment of Alexandrian poetics; on the other level, it transforms tenets of Egyptian ideology into the language of Greek poetry. Both levels resolve into unity. The Apollo of the Hymn to Delos is the ultimate source of both Kallimachean poetry and Ptolemaic kingship. It is thus that the old Pindaric vision of unity of government and music reappears in a new poetic and social context.[135]

2. Epigram 28 Pf. (2 G.-P.)

The Hymn to Delos ends with a hilarious ritual, in which sailors dance around the altar, beating it and biting the trunk of a tree with their hands turned backwards. The modern reader is inclined to take this as a device by which the poet undercuts the seriousness of what he has said before. The poet would thus be ironic in the extreme, toying with his audience. Before coming to such a conclusion, we should try to understand the function of Kallimachean humor, in particular since this will be a crucial factor for our discussion of the Coma . As an example I wish to take Epigram 28. We must be brief and focus on what is important in the present context.[136] First lines 1-4:

[134] This version of the oracle h known from two papyri which, in part, supplement each other. Only one version is published (PSI 982 = CP Jud . 3.520 [1964], cf. Gnomon 40 [1968]: 256); I shall publish the other in the P. Oxy . series in the near future. Presently no dependable text of the oracle is available.

[135] See Pyth . 1; Bing, Muse , 110-128 and 139-143; and below, n. 160.

[136] My reading of the epigram is indebted to A. Henrichs, "Callimachus Epigram 28: A Fastidious Priamel," HSCPh 83 (1979): 207-212; also see, for example, E.-R. Schwinge, Künstlichkeit von Kunst: Zur Geschichtlichkeit der alexandrinischen Poesie , Zetemata 84 (Munich, 1986), 5-9 ( = WJA NF 6a [1980]: 101ff.); Gow-Page's commentary 2:155-157; P. Krafft, "Zu Kallimachos' Echo-Epigramm (28 Pf.)," RhM 120 (1977): 1-29 (with a critical review of then recent research); see also E. Vogt, "Das Akrostichon in der griechischen Literatur," A&A 13 (1967): 85f., and C. W. Müller, Erysichthon: Der Mythos als narrative Metapher im Demeterhymnos des Kallimachos , Abh. Ak. Mainz, Geistes- und Sozialwiss. Kl. 13 (Stuttgart, 1987), 36. For further bibliography see Lehnus, Bibliografia Callimachea , 295-297.

I loathe the cyclic poem and I do not enjoy

a road which leads many people hither and thither;

I hate a meandering darling, and from a public fountain

I do not drink. I am sick of all that is public.

Lysanies, yeah, you are my handsome one, hand some—but before this

is said, echo responds distinctly: "in someone's hand!"[137]

Kallimachos begins this negative priamel with five rejections in four lines. The first two lines offer two pair of rejections of increasing length; the next two lines combine two other examples, this time of decreasing length, with the preliminary conclusion drawn from all four examples. In the first pair of rejections (lines 1-2), Kallimachos combines his intensive but almost prosaic distaste for cyclic poetry (

)[138] with an ambiguous refusal dressed in the traditional metaphor of the highway ("a road which leads many people hither and thither"). That Kallimachos will later take up the metaphor in his prologue to the edition of the Aitia (27f.) in four books and elevate it to a command Of Apollo (see below) stresses the theoretical character of this statement. It refers to Pindar,[139] who had used the metaphor of riding on a busy street

)[138] with an ambiguous refusal dressed in the traditional metaphor of the highway ("a road which leads many people hither and thither"). That Kallimachos will later take up the metaphor in his prologue to the edition of the Aitia (27f.) in four books and elevate it to a command Of Apollo (see below) stresses the theoretical character of this statement. It refers to Pindar,[139] who had used the metaphor of riding on a busy street

[138] The precise meaning of the word is uncertain, and it could indeed be intentionally ambiguous (H. J. Blumenthal, CQ 28 [1978]: 125-127, esp. 127). Later the word overwhelmingly referred to cyclic poetry, but Numenius uses the word for "common," "conventional," that is, "un-Platonic" (F 20 des Places). The suggestion that Numenius may have taken this usage from Kallimachos' epigram (Blumenthal), implies that Kallimachos' text would either unambiguously mean "common" or Numenius misunderstood it in this way. G. O. Hutchinson (Hellenistic Poetry , 79 n. 104) prefers "banal or commonplace poem"; see also C. Meillier, Callimaque et son temps , Publ. de l'Univ. de Lille 3 (Lille, 1979), 124.

for the imitators of Homer—in Kallimachos' terms the authors of cyclic poetry. Thus the knowledgeable reader expects the road metaphor also to speak about poetics, but he soon realizes that in the third example, the first member of the following dicolon (line 3), the poet turns to his rejection of an unfaithful boy. Thus the reader wonders whether the preceding road metaphor should be taken in a similar sense. In a small poem of the sixth century, extant in the Theognidea , this metaphor is indeed used for the boyfriend who walks the road to another lover.[140]

Kallimachos' third example means precisely what it says: he hates an unfaithful boy. Proceeding to the fourth rejection, the reader recognizes immediately that, because of the form of the negative priamel, the fountain must represent something detestable, hence not Hippokrene, the fountain of the Muses. He recalls another passage of the Theognidea (959ff.) where the poet says that when he drank from a dark-watered fountain  —that is, from a deep fountain in a shady place—the water seemed sweet and dean to him; but now the fountain is polluted, water is mixed with water, and the poet will drink from another spring or river.[141] The sense is again erotic. But whereas in the Theognidea the fountain is clearly described as dark-watered and then as polluted, Kallimachos' fountain needs no such qualification. At this point the reader notices that Kallimachos throughout the epigram (as well as in his other poetry) mixes prosaic with poetic diction. Line 1, "the cyclic poem"

—that is, from a deep fountain in a shady place—the water seemed sweet and dean to him; but now the fountain is polluted, water is mixed with water, and the poet will drink from another spring or river.[141] The sense is again erotic. But whereas in the Theognidea the fountain is clearly described as dark-watered and then as polluted, Kallimachos' fountain needs no such qualification. At this point the reader notices that Kallimachos throughout the epigram (as well as in his other poetry) mixes prosaic with poetic diction. Line 1, "the cyclic poem"  is a prose expression, a fact which is made more impressive by the contrast to the preceding poetic word (

is a prose expression, a fact which is made more impressive by the contrast to the preceding poetic word ( , "I hate"); and the series of things hated ends with

, "I hate"); and the series of things hated ends with  , "I am sick," again a prosaic word.[142] These prosaisms remind the contemporary reader that, in plain language as used in Egypt, the word "fountain" (

, "I am sick," again a prosaic word.[142] These prosaisms remind the contemporary reader that, in plain language as used in Egypt, the word "fountain" ( , a word used in prose as well as in poetry) normally denotes a fountain that is public or on an estate where it is used for professional purposes—surely a very popular and hence, for Kallimachos, undesirable place.[143] This is the primary sense needed in the epigram.

, a word used in prose as well as in poetry) normally denotes a fountain that is public or on an estate where it is used for professional purposes—surely a very popular and hence, for Kallimachos, undesirable place.[143] This is the primary sense needed in the epigram.

1.

Golden seals, middle of and cent.; Louvre Bj 1092 and 1093; from H. Kyrieleis,

Bildnisse der Ptolemäer, Arch. Forsch. 2, DAI (Berlin, 1975), pl. 46.

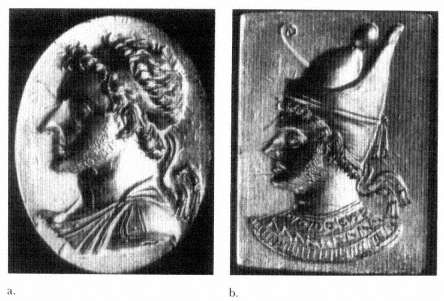

2 a & b.

Berenike II from Thmuis (Tell Timai), Greco-Roman Museum in Alexandria

inv. no. 21739 and 21736, Photos by D. Johannes, from W. A. Daszewski, Corpus

of Mosaics from Egypt I, Aegyptiaca Treverensia 3 (Mainz, 1985), pl. A

(after p. 7; cf. pll. 32 and 42a; cat. no. 38) and B (after p. 40; cf. pl. 33;

cat. no. 39). Also see, e.g., E. Breccia, Le Music Gréco-Romain,

1925-1931 (Bergamo, 1932), pll. A, LIV 196 (both [a]) and LIII 194 (b), M. Rostovtzeff, The Social

and Economic History of the Hellenistic World (Oxford, 1941) I pl. XXXV;

cover of F. W. Walbank, The Hellenistic World (Cambridge, Mass., 1982), both (a).

3.

Gold octadrachms with portrait of Arsinoe III in the British Museum (BMC Ptolemies

67, 1-2, pl. 15.6) and in Glasgow, from H. Kyrieleis, Bildnisse der Ptolemäer, Arch. Forsch.

2, DAI (Berlin, 1975), pll. 88.1-2 (cf. pp. 102f.); see also J. N. Svoronos,

All four first members of the priamel can be taken in a literal meaning: rejection of cyclic poetry, a crowded street, an unfaithful lover, and a public fountain. But the second and fourth members express also metaphorical meanings, again amounting to rejection of both popular poetry and an unfaithful lover. Thus, the metaphorical meaning of the street and the fountain vacillates between the parameters determined by the two rejections that have literal meaning only.[144] Moreover, the layers of the literal and metaphorical meanings prepare for the fifth member of the negative priamel, the generalization summarizing all levels of interpretation: I am sick  of everything that is popular.

of everything that is popular.

The following cap or climax (lines 5-6) turns the priamel, already presented in hilarious artistry, on its head. Taking up the erotic elements, Kallimachos begins the positive conclusion of the negative priamel as one should expect. "Lysanies, yeah, you are handsome, handsome:" nekhi kalos kalos. " Expressions like  are common confessions by which a Greek lover declared his love to a boy. Kallimachos repeats the adjective, as did the girl addressing Daphnis in Theokritos' (?) Boukoliastai 2 (8),73. Such duplication is both archaic and colloquial, as a Greek reader conscious of his language would hear instantly.[145] But as soon as the audience believes it understands the epigram, its expectation is deceived. Kallimachos seems himself to walk the popular road, but at the same time the repetition prepares for the effect of the echo. He plays only with the echo of his last words: nekhi kalos kalos ; and it is broken twice. When the first echo arrives, its very beginning is broken off: only allos is heard, and before this echo reaches the second kalos , this word is made inaudible by the return of the second

are common confessions by which a Greek lover declared his love to a boy. Kallimachos repeats the adjective, as did the girl addressing Daphnis in Theokritos' (?) Boukoliastai 2 (8),73. Such duplication is both archaic and colloquial, as a Greek reader conscious of his language would hear instantly.[145] But as soon as the audience believes it understands the epigram, its expectation is deceived. Kallimachos seems himself to walk the popular road, but at the same time the repetition prepares for the effect of the echo. He plays only with the echo of his last words: nekhi kalos kalos ; and it is broken twice. When the first echo arrives, its very beginning is broken off: only allos is heard, and before this echo reaches the second kalos , this word is made inaudible by the return of the second

echo (n)ekhi . In turn the second echo weakens and immediately fades away. Thus all that is produced is allos ekhi .[146]

In part the pun is based on the pronunciation  and

and  , which at the time did not yet dominate the scene but was obviously used by some people. Kallimachos himself plays in other poems with the pronunciation of

, which at the time did not yet dominate the scene but was obviously used by some people. Kallimachos himself plays in other poems with the pronunciation of  and

and  ,[147] and the only additional surprise in the echo's pun is the fact that the i of ?C? becomes i of

,[147] and the only additional surprise in the echo's pun is the fact that the i of ?C? becomes i of  in the metrical position at the end of the line, where a short vowel would be lengthened by the following pause. There may be an additional sound effect: the i , the last sound of the echo (and the epigram), imitates the echo as slowly fading away. Kallimachos plays with pronunciations which at his time occurred but were not frequent; and it might have been precisely for this reason that he found such puns intriguing.

in the metrical position at the end of the line, where a short vowel would be lengthened by the following pause. There may be an additional sound effect: the i , the last sound of the echo (and the epigram), imitates the echo as slowly fading away. Kallimachos plays with pronunciations which at his time occurred but were not frequent; and it might have been precisely for this reason that he found such puns intriguing.

Another related element of this pun is the fact that at the moment when the climax (Lysanies) is topped and the reader's expectation is turned upside down, Kallimachos uses the emphatic  , a word which may not have been as rare as its attestations in the surviving literature suggest.[148] In the context of the poem the use of the emphatic word

, a word which may not have been as rare as its attestations in the surviving literature suggest.[148] In the context of the poem the use of the emphatic word

[146] I.e., (nekhi k )alos(kalos n )ekhi (kalos kalos ). The right explanation was given by K. Strunk, "Frühe Vokalveränderungen in der griechischen Literatur," Glotta 38 (1960): 74-89, esp. 84f.

seems to sound somewhat droll. The emphasis precedes the peripateia. What makes the pun burlesque, however, is its content. Lysanies, who for a moment seems to be the climax of the priamel, is somebody else's darling. Kallimachos' likes are not better than his dislikes. The humorous reversal of the climax depends on the meaning of the sentence as well as on the play with the sound pattern.

The climax of the priamel undercuts, first, its positive conclusion, that Kallimachos loves Lysanies. This boy is not what his name promises, and he puts no end to his lover's heartache.[149] The name was actually in use, and Lysanies could therefore be a real person. But I doubt that this is the reason why Kallimachos invokes this name. He rather stands for this type of boy. He is public property and thus must belong to what Kallimachos hates. Second, the entire buildup of the negative priamel is undercut. Does the joke therefore negate the seriousness of Kallimachos' erotic dislikes? That is hardly the case. And is it inconceivable that Kallimachos meant to rescind his hatred of the cyclic (and other bad) poetry? The punch line makes fun of his own way of life and of his poetic principles; but his seriousness and his laughter are two sides of the same coin. What otherwise would have been an inflated, boastful, overserious poetical credo, is deflated by the humor and thus kept in civilized human proportions. It does not provoke rejection; it becomes acceptable.

We should bear this in mind as we now return to Ptolemaic kingship, specifically to Kallimachos' poem The Lock of Berenike . There we will find a deflation even of the sovereign, but done in such a way that, with a broad smile, even his apparently overwhelming power is put into a human context of friendship and love.[150]

3. The Lock of Berenike

As far as we can tell, Kallimachos is more subtle in the Lock of Berenike than in the Hymn to Delos . The poem centers on the concept of divine kingship. Its imagery suggests in poetic playfulness that the queen, the

[149] Here I follow a suggestion communicated orally by T. Gagos.

[150] Cf. G. O. Hutchinson's general statement (Hellenistic Poetry , 32): Kallimachos' "work characteristically explores the effects which lie between absolute seriousness and entire deflation. One must not seek, therefore, to resolve the poetry into either extreme—nor even rest content with asserting that it belongs to neither."

"daughter" of the new deity Arsinoe II, must be divine too. The deification of the queen is anticipated by the catasterism of the lock.

The Lock of Berenike may be dated to September 245 BC , when the astronomer Konon detected the constellation of the lock after its heliacal rising.[151] This was about two years before Euergetes added Berenike II and himself to the Alexandrian cult of Alexander and the Gods Adelphoi (section II.1.b [3]). Thus, both Konon's "discovery" and Kallimachos' poem reflect the mood at the court, which may even have initiated the disappearance of the lock.[152] If the hair can become a star, the queen should be divine too. This is an urbane compliment, significant of the atmosphere of the court and of the way in which the issue of divine kingship was accepted and playfully propagated.

The poem can be understood within the parameters of the Greek tradition,[153] and yet the entire institution of divine kingship developed in Egypt under the influence of the Egyptian reality. Hence we will take our clue from Kallimachos, and in a few passages question whether there is an additional Egyptian side to it. But as in the case of the Hymn to Delos , "Egyptian" will refer only to the layers of Egyptian beliefs which at the time were easily accessible to the Greeks.

Three preliminary reminders are essential before we begin our reading of the Lock of Berenike . (1) The Lock was the last poem of the Aitia .

[151] See also below. For the heliacal rising on September 2-8 as well as for other astronomical data relevant for the interpretation of the poem see N. Marinone, Berenice da Callimaco a Catullo (Rome, 1984), esp. 29-44. Recently an attempt has been made to advance the date to September 246, because around September 10 of that year the planet Venus, alias the morning star, would be relatively dose to the Coma Berenices. The planet, of course, is the star of Aphrodite, that is, in the present context, of Aphrodite-Arsinoe. An allusion to this star could be expected (S. West, "Venus Observed? A Note on Callimachus, Fr. 110," CQ 35 [1985]: 61-66). But, according to Catullus, Kallimachos must have dated the catasterism to the heliacal rising of the following year (as is maintained by common opinion): Euergetes became sole ruler on January 27/28, 246 (Dios 25). When, later in the year, he went to war, the queen promised the sacrifice of her lock, but the promise was only fulfilled after his return around September 3, 245. Cat. 66.33-34: atque ibi me cunctis pro dulci coniuge divis / . . . pollicita es, / si reditum tetulisset. is haut in tempore longo / captain Asiam Aegypti finibus addiderat. / quis ego pro factis caelesti reddita coetu / pristina vota novo munere dissolvo . There is no reason to postulate a different chronology for Kallimachos. Hence, part of the chronology proposed by H. Hauben for the Syrian war of 246/5 should be revised. H. Hauben, "L'expédition de Ptolemée III en Orient et la sédition domestique de 245 av. J.-C.," APF 36 (1990): 29-37. For a bibliography on the Lock , see Lehnus, Bibliografia Callimachea , 104-113.

[152] West, "Venus Observed," 62 n. 7, 63 n. 14; H. P. Syndikus, Catull: Eine Interpretation , Impulse der Forschung 55 (Darmstadt, 1990) 2:199 n. 4.

[153] That Kallimachos' Lock of Berenike is exclusively based on Greek traditions was defended by H. Nachtergael in "Bérénice II, Arsinoé III et l'offrande de la boucle," CE 55 (1980): 240-253.

In all likelihood, Kallimachos edited the Aitia in two steps; the first edition consisted of books 1 and 2 only, which are cast in the form of a story told by the narrator, Kallimachos, about his dream encounter with the Muses: his initiation as successor to Hesiod (the somnium ), his questions, and the Muses' answers.[154] In his old age Kallimachos expanded the work of his younger days with two more books, mainly a collection of etiological poems which he had written over the years. He also added (a) the prologue against the Telchines (F 1.1-40) and (b) an invocation of the Muses in which the poet seems to have called upon them to remind him of the earlier encounter when they answered his questions;[155] and (c) he reworked the epilogue of the earlier edition (F 112), which now was to bridge the Aitia and the lambs[156] in the fashion in which transi-

[154] I follow P. Parsons' theory, essentially a combination of R. Pfeiffer's and E. Eichgrün's theories: "Callimachus: Victoria Berenices," ZPE 25 (1977): 1-50, esp. 49f.; cf. Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria 2:106f. nn. 11 and 12. For the structure of the first two books as a dialogue with the Muses, see now A. Harder, "Callimachus and the Muses: Some Aspects of Narrative Technique in Aitia 1-2," Prometheus 14 (1988): 1-14; Harder is mainly interested in explaining the dialogue with the Muses as an innovative and playful transformation of epic "dialogues" into a "diegematic" presentation.

[155] P. Bing, "A Note on the New 'Musenanruf' in Callimachus' Aetia ," ZPE 74 (1988): 273-275; this is an addendum to an observation by A. Kerkhecker, "Ein Musenanruf am Anfang der Aitia des Kallimachos," ZPE 71 (1988): 16-24; cf. also Hutchinson, Hellenistic Poetry , 81 n. 109.

tional lines connected the Iliad with the Aithiopis , Hesiod's Theogony with the Catalogue , and the Erga with the Ornithomanteia . Moreover Kallimachos' wording recalls the fashion in which a number of "Homeric" hymns dose with transitional lines that lead into another hymn or epic performance. To this we will return. Suffice it here to draw attention to the fact that Kallimachos gives the traditional feature a new function by using it as a bridge from one genre to the other.[157]

Sandwiched between the invocation of the Muses in the prologue to the later edition (above, [a]) and the somnium of the earlier edition (F 2), there survives a reference to the number 10 in a passage that is almost

[157] Kallimachos plays with this habit: transitional lines seem to turn separate poems into a cycle; but in Kallimachos' case the continuation is in a different genre. Both form and content separate the edition of his works from the negative connotations of a "cycle" and turn the old into a new concept. The use of this feature in the Hesiodic corpus might have made it attractive to Kallimachos.

totally lost. The London scholion explains this as the total number of the Muses or as their traditional number plus either Apollo or Arsinoe (F 2a.5-15 Pfeiffer 2 p. 102). Kallimachos clearly did not tell his readers who was added to the Muses, but the queen was an obvious candidate (see also the Florentine scholion ad F 1.45f. Pfeiffer 1 p. 7). This section of the poem may well come from what was originally the prologue of the edition of the first two books; but it was reworked and turned into the front piece of the device framing the edition of the four books. The epilogue participated in the same fate. Part of it was clearly written to cap the first edition: Kallimachos mentions  (his poetry; in the nominative) and the Charites as well as the

(his poetry; in the nominative) and the Charites as well as the  (both in the genitive). The Charites may be meant to remind the reader of the first aition of book 1 (on the Charites; F 3-7 with SH 249A), while the "lady" or "queen" recalls either Berenike or Arsinoe. Then a quotation from the beginning of the somnium follows.[158] This framing device connects the epilogue clearly with the early edition of books 1 and 2.[159] But then Kallimachos reworked the epilogue so that it would serve the later edition of the entire books 1-4 and now create a transition to the Iambs . The transitional link (line 9) imitates the transitional formulas of Homeric hymns (see n. 156). Hence it is preceded by "All hail, Zeus, also to you, and preserve the entire house of the lords." This line is preceded by another: "Hail, and bring (even) richer grace." The recipient of this first prayer is not known, but must be a deity of poetry, most likely Apollo. This, then, takes up the mention of Apollo in the prologue of the edition of the entire four books (F 1.21-29), and at this point the epilogue forms a framing device with the prologue of the later edition.[160] The meaning of

(both in the genitive). The Charites may be meant to remind the reader of the first aition of book 1 (on the Charites; F 3-7 with SH 249A), while the "lady" or "queen" recalls either Berenike or Arsinoe. Then a quotation from the beginning of the somnium follows.[158] This framing device connects the epilogue clearly with the early edition of books 1 and 2.[159] But then Kallimachos reworked the epilogue so that it would serve the later edition of the entire books 1-4 and now create a transition to the Iambs . The transitional link (line 9) imitates the transitional formulas of Homeric hymns (see n. 156). Hence it is preceded by "All hail, Zeus, also to you, and preserve the entire house of the lords." This line is preceded by another: "Hail, and bring (even) richer grace." The recipient of this first prayer is not known, but must be a deity of poetry, most likely Apollo. This, then, takes up the mention of Apollo in the prologue of the edition of the entire four books (F 1.21-29), and at this point the epilogue forms a framing device with the prologue of the later edition.[160] The meaning of  and

and  shifted correspondingly: from Philadelphos and Arsinoe II in the edition of books 1 and 2 to Euergetes and Berenike II in the edition of the entire four books.[161] Therefore,

shifted correspondingly: from Philadelphos and Arsinoe II in the edition of books 1 and 2 to Euergetes and Berenike II in the edition of the entire four books.[161] Therefore,

[158] Pfeiffer ad F 2.1-2; cf. C. A. Faraone, "Callimachus Epigram 29.5-6," ZPE 63 (1986): 53-56, esp. 55 n. 9.

[159] Knox, "Epilogue," thought that the entire epilogue also originally belonged to the edition of books 1 and 2; this must be modified in light of n. 155.

the same shift must apply to the tenth Muse of the prologue. What in the early edition (books 1 and 2) meant Arsinoe, may in the later edition (books 1-4) refer to Berenike. The framing between prologue and epilogue was a characteristic feature of both editions. Later, when discussing the end of the Lock of Berenike , we shall have to come back to this feature.

Books 3-4 lack the kind of structural coherence which the narration of his talks with the Muses provides, but they are nevertheless held together by a frame: the first poem is the Victoria Berenices (SH 254-269), which begins with an invocation of Berenike, "the holy blood of the Brotherly Gods."[162] The last poem is the Coma Berenices . Berenike functions in the third and fourth books in the same manner in which Arsinoe does in the first two books.

(2) The papyrus which records the Greek fragments of the Lock of Berenike omits Catullus' lines 79-88 and, on the other hand, adds a closing distich. Especially the latter fact confirms the suspicion that Kallimachos made some changes in his Lock when he added books 3 and 4 to the earlier two books of the Aitia (see below). Most likely the papyrus contains the original version of the poem whereas Catullus followed the version inserted into the Aitia .[163] Below I shall analyze this original version, but because of the very fragmentary nature of the Greek, I will frequently resort to the text of Catullus.

(3) A fundamental difference between Kallimachos and Catullus is the gender of the lock; Kallimachos' lock is male  , Catullus' lock is female (coma ). Both poets had words of the other gender at their disposal, although Kallimachos might have been restricted by the name given by Konon to the constellation. On the other hand, Kallimachos must have been in a position to influence this name; and, in any case, he

, Catullus' lock is female (coma ). Both poets had words of the other gender at their disposal, although Kallimachos might have been restricted by the name given by Konon to the constellation. On the other hand, Kallimachos must have been in a position to influence this name; and, in any case, he

[163] Cat. 66.79-88 is either an addition by Catullus (as most scholars now assume; see for example, Hutchinson, Hellenistic Poetry , 323f.) or by Kallimachos for his second edition. For a relatively recent discussion of the question see Marinone, Berenice , 59-67. The passage offers an additional aition for a sacrifice of ointment before connubial sex (79-80, nunc vos optato quas iunxit lumine taeda / non prius unanimis corpora coniugibus / tradite ). If such a sacrifice is offered by her quae se inpuro dedit adulterio (84), it will not have the desired effect (87f., concordia, amor adsiduus ). The contrast between the two groups of women makes it dear that the sacrifice to the lock is not a custom of the wedding night (as commentators believe), but part of the woman's preparation for making love when she puts on her perfumes. This interpretation fits the lock's complaint that he never received such ointments when he was on the head of the queen, then still a virgin (see later in this section and n. 200); and therefore this aition is much better integrated into the context of the poem, as modern critics believe (see, for example, West, "Venus Observed," 64f. n. 24).

was free to choose the gender Of the other hairs.[164] But when Kallimachos' lock tells us that the hairs which remained on the queen's head longed for him, these are termed female hairs  and called "sisters" (51). The lock is distressed that he is no longer on the head of the queen (76). His fate substitutes for, and replaces, the temporary separation of the queen from her brother and husband. Thus, the separation of the lock from the queen and the separation of the king from his sister-wife are functionally related. The former replaces the latter. The use of the male or female gender clearly adds a specific flavor to the poem. In order to retain the almost sexual tension created by Kallimachos' male lock, I will treat the lock in my translations and paraphrases as male when I refer to Kallimachos and to Catullus' original, although the use of the male pronoun will sound strange.

and called "sisters" (51). The lock is distressed that he is no longer on the head of the queen (76). His fate substitutes for, and replaces, the temporary separation of the queen from her brother and husband. Thus, the separation of the lock from the queen and the separation of the king from his sister-wife are functionally related. The former replaces the latter. The use of the male or female gender clearly adds a specific flavor to the poem. In order to retain the almost sexual tension created by Kallimachos' male lock, I will treat the lock in my translations and paraphrases as male when I refer to Kallimachos and to Catullus' original, although the use of the male pronoun will sound strange.

We now turn to the poem. Using the traditional form of Rollengedicht (or dramatic monologue)[165] —a form as old as Archilochos' Iambs (e.g., F 19 W.)—Kallimachos lets the curl, cut off from the head of the queen, tell us his story. The narrator needs no introduction. He begins with the event which is most important for him: Konon's discovery of the catasterized lock both in the air ( , 7) and in his maps of the stars (cf. 1:

, 7) and in his maps of the stars (cf. 1:  ). No new star needed to be discovered; only the shape of the constellation, now known as

). No new star needed to be discovered; only the shape of the constellation, now known as  or coma , had to be recognized. From this event, which is most important to the narrator, he jumps back in time to a brief explanatory mention of Berenike's vow at the beginning of the Syrian war to sacrifice a lock from her head (9-11), and to the wedding of the royal couple (11; 13-18). The lock states, with some exaggeration, that the king went to the war immediately after the wedding[166] —in reality about half a year after his accession and presum-

or coma , had to be recognized. From this event, which is most important to the narrator, he jumps back in time to a brief explanatory mention of Berenike's vow at the beginning of the Syrian war to sacrifice a lock from her head (9-11), and to the wedding of the royal couple (11; 13-18). The lock states, with some exaggeration, that the king went to the war immediately after the wedding[166] —in reality about half a year after his accession and presum-

[165] Cf., for example, Schwinge, Künstlichkeit , 69-71.

[166] There were political reasons for this war. But it should also be said that the pharaoh was expected to engage in warfare immediately after his accession: thus he fulfilled his role of being Horus victorious over Seth and avenging his father; see E. Hornung, "Politische Planung und Realität im alten Ägypten," Saeculum 22 (1971): 54f.; Koenen, "Gallus," 123 with n. 30.

ably well after the wedding (cf. n. 151). In the lock's report, however, the wedding, the beginning of the war, and the vow of the sacrifice form a unit of almost simultaneous events. Up to the wedding and the events following it, the narrator turned backward in time ("rückläufig," Kroll), but from here on the narration will follow the chronological order: the departure of the king (19-32) with the vow of the lock (33-35), then the kings victory and the redemption of the vow to sacrifice a lock (36-50), and next the catasterization: first the mourning of the sister hairs (51f.); second, a gust of wind that carried the lock into the sea (52-58); third, the rising of the lock as a constellation before sunrise (59-64); and fourth, his arrival in his new heavenly position (65-76). With these events the lock's story reaches again the point from which it departed: his discovery by Konon (1-9). But this is not yet the end. Remembering that he has never tasted perfumes, he asks for such sacrifices (89-92; also Catullus 79-88 [see (2) above]). His request constitutes an additional aition (or two) which, from the point of view of the story, points into the future, that is, into the time of the reader of the poem. The basic structure of the narrative, then, starts out with the most important event from the point of view of the narrator, jumps back to the earliest part of the story, and from there on follows the chronological order till it reaches the event from which it began and, passing beyond that point, reaches out to a later event and the presence of the original reader. This narrative structure, particularly known from Pindar and used by Kallimachos elsewhere with elaboration and complications, has been called "complex lyric narrative" in differentiation from the "simple lyric narrative" which omits the last step and ends when it has returned to its beginning.[167] By using the aition as the element which continues the story beyond the point of its departure, Kallimachos varies the scheme. There are other complications, like the occasional mention of past events outside the narrative frame of the story and the very emotional reactions and reflections on the main steps of the narrative. But these we cannot examine in the present context.

[167] The third type of narrative, not relevant in our context, follows strictly the chronological order; because of the frequency of its occurrence in Homer, it is called the "epic narrative." See W. J. Slater, "Pindar's Myth," in Arktouros: Hellenic Studies Presented to B. M. W. Knox on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday , ed. G. W. Bowersock, W. Burkert, and M. C. J. Putnam (Berlin and New York, 1979), 63-70, esp. 63-65; the concept is based on W. Schadewaldt's observations, Iliasstudien , 3d ed. (Darmstadt, 1966), 83ff. For narrative structures in Kallimachos and his use of rather complicated and elaborate versions of "complex lyric narrative," sometimes with flashbacks and flash-forwards into events outside the narrative frame, see Lord, Pindar , 50-73, 146-157.

When the lock describes Konon's work with due learnedness, he also establishes the theme of love (line 5): it is love that brings Selene down from the starry heaven, and love that turns Berenike's lock into a constellation of stars. The queen had pledged the lock "to all the gods" for the safe return of her husband from his war. As is seen in Catullus' translation, the two wars, the nocturnae rixae and the real war (vastatum finis iverat Assyrios ) are set in contrast to each other (11ff.). Not much is said about the real war, as if the lock wanted to state that love, not history and war, are the métier of the poet. In other words, the lock sticks to Kallimachos' program.[168]

Interrupting the narration of his fate, the lock begins to ask himself questions about the amusing behavior of brides on the wedding night, thus anticipating the reader's reaction to the story (15ff.). But, in answering these questions, the lock amusingly alludes to Berenike's love and tears at the separation from her husband and asks her teasingly as if she were present: "Or did you bewail, not the empty bed when you

were left alone, but the sad departure of your dear brother?" (21f.).[169]

We saw earlier that indeed the love between queen and king, in particular the love between brother and sister, had come to describe the holy nature of kingship, in spite of the Greek distaste for such marriages (section II.1.d, Philadelphos). Moreover, as we were reminded (see [1] above), Kallimachos begins the second part of the Aitia (books 3 and 4) by invoking Berenike II, the "blood of the Brotherly Gods." There the use of the word "blood" is pointed, since Berenike was the daughter of Magas, Philadelphos' brother by adoption.[170] In the Lock Kallimachos accepts the official version of Euergetes and Berenike II as a brother-and-sister couple, and yet in his witty way he removes the seriousness. Thus, the marriage of brother and sister—unbearable to Greek ears and yet, as we saw (section II.1.d, Philadelphos), an essential issue of the ideology of Ptolemaic kingship—appears to be the most natural thing in the world.

The lock continues his story (35ff.): the victorious king returned, and the queen cut off a lock of hair. In teasing words the lock apologizes to the queen for having left her; he swears by her head from which he has been cut, and adds: "May whoever has sworn falsely get what he deserves" (41).[171] An additional playful element is revealed by the fact that

[168] I owe this observation to B. A. Victor, at the time a participant in my course on Kallimachos.

[169] an tu non orbum luxti deserta cubile, / sed fratris cari flebile discidium?

[170] Philadelphos' father, Ptolemy I (Euergetes' grandfather), had adopted Berenike's father, Magas, on marrying Magas' mother.

[171] digna ferat quod si quis inaniter adiurarit .

the official Ptolemaic oath was sworn by the names of the king and the queen. The practice was pharaonic, albeit in a Greek dress.[172] Both in good Greek form and close to Kallimachos' words, the oath regularly contained the phrase: "If I swear the truth, may I do well; if I swear falsely, may I suffer the opposite."[173] Of course, the lock swears by the queen's head from which he comes, and by her life. In the context of the poem the lock conveniently forgets the king.

As the lock tells us in his oath, he left the head of the queen against his will: twice invita (39f.)[174] Catullus' invita corresponds to Kallimachos'  : he has not committed any

: he has not committed any  . Iron has cut even Mount Athos for Xerxes, as the lock says again with hilarious exaggeration. Kallimachos calls Mount Athos the "spit of your mother Arsinoe."[175] If Euergetes and Berenike are brother and sister, then Arsinoe is also Berenike's mother, concludes Kallimachos.

. Iron has cut even Mount Athos for Xerxes, as the lock says again with hilarious exaggeration. Kallimachos calls Mount Athos the "spit of your mother Arsinoe."[175] If Euergetes and Berenike are brother and sister, then Arsinoe is also Berenike's mother, concludes Kallimachos.

Two approaches need to be combined in order to understand Arsinoe's "spit": (a) one is Greek and learned, (b) the other is a play with Egyptian thoughts and symbols.

(a) On the one hand, the "spit" alludes to Sophokles' almost proverbial expression: "Athos casts his shadow on the back of the Lemnian cow."[176] The "cow" was a statue on the island of Lemnos which, before sunset , was struck by the shadow of Mount Athos, the "spit." By itself, however, this explanation does not explain why Kallimachos lets the sun pass directly over Mount Athos, when from the vantage point of an Alexandrian observer such a northerly route is impossible.[177]

[174] For the repetition of invita see above, section III.2 with n. 145.

[175] 43ff.:

[](b) On the other hand, the scholiast tells us that "spit" means "obelisk," thus providing us with a synonymous word and with a different due. According to Egyptian symbolism, the top of the obelisk was struck by the first rays of the sun. Hence in the morning Athos "is passed over by the sun," and the question of an Alexandrian viewpoint does not enter the interpretation. Moreover, there was a famous obelisk in front of the unfinished temple of Arsinoe.[178] In other words, the true obelisk of this goddess is Mount Athos, where the rays of the sun appear in the morning.

The "spit" of Athos belongs to Arsinoe II, who before her marriage to her brother Philadelphos was married to Lysimachos. Lysimachos' realm was based in Thrace but, at the height of his power, included Macedonia and the Chalcidice among many other possessions; these were Arsinoe's realms too.[179] At the time of our poem, in the Third Syrian War, Ptolemaios III Euergetes had again extended his claims to the north at least as far as Thrace. In short, the phrase

contains a territorial claim (although to our knowledge Euergetes was never able to materialize it).[180] But this claim is dressed in metaphorical language alluding to the morning rays of the sun ("Arsinoe's obelisk") and the wide casting of the evening shadows ("Arsinoe's spit"); the two explanations complement each other. They describe the journey of the sun which, as we have seen, defines the realm of the Egyptian king and pharaoh (section III.1). In addition, the Greek side of the explanation is rooted in a learned allusion to poetry, but this learnedness remains subordinate to Kallimachos' poetical intentions.

contains a territorial claim (although to our knowledge Euergetes was never able to materialize it).[180] But this claim is dressed in metaphorical language alluding to the morning rays of the sun ("Arsinoe's obelisk") and the wide casting of the evening shadows ("Arsinoe's spit"); the two explanations complement each other. They describe the journey of the sun which, as we have seen, defines the realm of the Egyptian king and pharaoh (section III.1). In addition, the Greek side of the explanation is rooted in a learned allusion to poetry, but this learnedness remains subordinate to Kallimachos' poetical intentions.

The lock deplores that he was forced to leave the head of the queen (who after all was the one who cut him off). Even Mount Athos had to submit to the force of iron when Xerxes built the canal for his fleet. What could a small lock do against iron? There follows a magnificent curse of the first inventors of iron, the Chalybes known from Aischylos (48ff.). Irony abounds; it feeds on the contrast between the curse and

[178] See Fraser, Ptolemaic Alexandria 2:1024.

[179] For the extension of Lysimachos' realm see E. Will, Histoire politique du monde hellénistique , 2d ed., Ann. de l'Est (Nancy, 1979), vol. 1, part 1, chap. 2A. For a brief period after the death of Lysimachos, she was also married to Ptolemaios Keraunos, whom his troops proclaimed as "king of Thrace and Macedonia" and who made Arsinoe queen. He tried to strengthen his claim to this throne through this marriage. But since this marriage ended with the murder of Arsinoe's children Lysimachos and Philippos, Kallimachos will not have wished to remind Berenike and the audience of this period of Arsinoe's participation in the rule of Thrace and Macedonia. Mount Athos is also the place where gods watch what is going on (Hymn to Delos 125ff.; F 228.47f. [see below]).

[180] Will, Histoire 1.2, chap. 4C2 Adoulis inscription and 3 ("Les acquisitions lagides en 241"); R. S. Bagnall, The Administration of the Ptolemaic Possessions outside Egypt , Col. Stud. in the Class. Tradition 4 (Leiden, 1976), 159f. Euergetes had to cut short his campaign because of an insurrection in Egypt; see Hauben, Expedition , esp. 32ff.

the small present occasion, which is trivial for the reader, but not for the curl.[181]

The precise sequence of the following events remain the secret of Kallimachos and the gods; but the most likely scenario is this: on the grounds of the temple of Arsinoe Aphrodite Zephyritis—the recently deified goddess who passed for Berenike's mother—on Cape Zephyrion, Berenike cut off and dedicated the lock to this goddess and, to be sure, to all gods.[182] The sister hairs were still longing for him—and Kallimachos may have imagined that they did so during the ceremony (51)—when Zephyr, the west wind, caught the lock and swept him into the sea,[183] the "(pure) bosom" of Arsinoe Aphrodite. From there the new constellation would rise on the next morning before sunrise,[184]

[181] Cf. Syndikus, Catullus 2:210: "Aber hier sind die Bilder so hoch gegriffen, dass die Diskrepanz zwischen Bild und Gemeintem komisch wirkt."

washed by the sea ( , cf. 63) like other stars.[185]

, cf. 63) like other stars.[185]

The west wind is described in very dense and symbolic language: he is the brother of the Aithiopian Memnon, hence the son of Dawn (Eos) the mother of the winds (Hes. Theog . 378). The Aithiopian Memnon was the last hero killed by Achilleus; and the Greeks connected him with monuments in Egyptian Thebes in the south of the country, close to Aithiopia. But these facts help little to explain the appearance of the brother of Memnon in Kallimachos' Lock . Nor is this west wind called "brother of Memnon" in order that he, as the son of Dawn, may be an appropriate vehicle for transporting the lock to heaven.[186] This he does

[186] ". . . and it is most suitable that Zephyros, son of Eos the Dawn and half brother of Memnon, should be the messenger who bears the lock to the queen-goddess," that is, to Aphrodite, whose "heavenly home is the planet Venus, the morning and the evening star" (Huxley, "Arsinoe Lokris," 242).

not do, as we have just seen. The lock rather follows his new nature and, before sunrise, begins his daily journey. With regard to Memnon's brother, however, there is another detail that may be helpful: in Quintus Smyrnaeus, the epic poet some 500 years younger than Kallimachos, the wind gods carry their fallen brother Memnon from the Trojan battlefield to his burial place on the Mysean river Aisepos (550-569, 585-587).[187] This part of the story is probably much older. If so, then Kallimachos' invocation of one of these wind gods as "brother of Memnon" introduces a heroic model for the rape of the lock. Why should Memnon's brother not do again what he once did to save his brother?

Next we are told that Zephyros lets his "swift" wings circle (53:

). This picks up a proverbial phrase which first occurs in a fable told by Archilochos, where the eagle "circles the swift wings" (

). This picks up a proverbial phrase which first occurs in a fable told by Archilochos, where the eagle "circles the swift wings" ( , 181.11 W.); elsewhere "words" or "love" are also said to travel in the same way. Kallimachos changes one word of the phrase

, 181.11 W.); elsewhere "words" or "love" are also said to travel in the same way. Kallimachos changes one word of the phrase  , partly, but not exclusively, for metrical convenience.

, partly, but not exclusively, for metrical convenience.  also recalls Balios, one of the horses of Achilleus in the Iliad , fathered by Zephyr, "that 'flies' with the speed of the winds" (16.149) and "runs with the breeze of Zephyr, which they say is the lightest thing of all" (19.415f.).[188] Kallimachos avoids the name of Balios; instead he uses an etymological pun.

also recalls Balios, one of the horses of Achilleus in the Iliad , fathered by Zephyr, "that 'flies' with the speed of the winds" (16.149) and "runs with the breeze of Zephyr, which they say is the lightest thing of all" (19.415f.).[188] Kallimachos avoids the name of Balios; instead he uses an etymological pun.

Further, the wind that moves his wings like an eagle is the Locrian horse of Arsinoe with the purple girdle (54).[189] The girdle identifies Ar-

sinoe with Aphrodite. The rape of the lock is engineered by the deity who should have the greatest understanding: the mother and predecessor of the queen, who is herself a manifestation of Aphrodite and an epiphany of the love of the queen and sister. In Theokritos it is Aphrodite who snatched away  Berenike I, the mother of Philadelphos and Arsinoe II, before she reached Acheron; and she made her immortal (Ptol . 46ff.; Adon . 106ff.). The servant of this Arsinoe is destined to pick up the lock and to sweep him most likely into the sea, as I said. He is Locrian, that is, he comes as the west wind from Lokroi on the south Italian coast; it hits the temple precinct of Zephyrion, and it is most likely here that he catches the lock. A Pompeian painting shows Zephyr in human shape and with huge wings, carrying Aphrodite on his shoulders and wings.[190]

Berenike I, the mother of Philadelphos and Arsinoe II, before she reached Acheron; and she made her immortal (Ptol . 46ff.; Adon . 106ff.). The servant of this Arsinoe is destined to pick up the lock and to sweep him most likely into the sea, as I said. He is Locrian, that is, he comes as the west wind from Lokroi on the south Italian coast; it hits the temple precinct of Zephyrion, and it is most likely here that he catches the lock. A Pompeian painting shows Zephyr in human shape and with huge wings, carrying Aphrodite on his shoulders and wings.[190]

But this wind is also described as a horse, and the winged wind-horse has caused many headaches. Winds, we are told by interpreters of this poem, are horsemen, not horses, at least before Quintus Smyrnaeus and Nonnos.[191] But on the poetical level, the horse is the consequence of the

[190] Casa del Naviglio (6.10.11); E. Schwinzer, Schwebende Gruppen in der Pompejanischen Wandmalerei , Beitr. z. Arch. 11 (Würzburg, 1979), pl. 4.2; Zwierlein, "Weihe," 289. Some twenty-five years ago I saw a silver statuette in an antiquities shop in Cairo (and I have photographs of it), which depicts an eagle stretching out his wings; on the wings rest a bearded man and a woman; the man puts his right arm around her shoulder. I suspect that, alluding to the rape of Ganymede, it depicts the journey to a blessed afterlife. Cf. nn. 193, 194.

allusion to Homeric Balios, as I have just argued. We are not supposed to imagine the picture; we rather recognize the pun: the wind functions like the Homeric horse Balios, swift like the wind.[192] According to Quintus Smyrnaeus, it is the destiny of Achilleus' divine horses, Balios and Xanthos, to bring Neoptolemos, Achilleus' son, by order of Zeus to the Elysian fields.[193] Horses were known to have performed similar tasks in earlier literature. When Poseidon raped Pelops, he transported him on golden mares  to Zeus's lofty house (Pind. Ol . 1.40-43). But such ideas were not restricted to literature. From the middle of the third century through the second century BC terracotta vases of unusual shape are found in South Italian tombs: the upper part of these vases is molded in such a way that the front halves of two, three, or four horses appear galloping upward. On top of the vases are stands for one or more figures, sometimes winged and sometimes not. Paintings on the vases show, among other things, winged figures and horses. The vases with the chariots pulled by horses represent the journey of the soul to heaven. In short, the horses are connected with the idea of snatching man from death and bringing him to his final home.[194]

to Zeus's lofty house (Pind. Ol . 1.40-43). But such ideas were not restricted to literature. From the middle of the third century through the second century BC terracotta vases of unusual shape are found in South Italian tombs: the upper part of these vases is molded in such a way that the front halves of two, three, or four horses appear galloping upward. On top of the vases are stands for one or more figures, sometimes winged and sometimes not. Paintings on the vases show, among other things, winged figures and horses. The vases with the chariots pulled by horses represent the journey of the soul to heaven. In short, the horses are connected with the idea of snatching man from death and bringing him to his final home.[194]

[192] O. Zwierlein now interprets the "horse" as a metaphor for the function in which Zephyros as a young man carries off the lock ("Weihe," 288).

In South Italy the soul was also represented as riding on a horse to heaven.[195] Kallimachos may give us a deliberate hint with his Zephyros coming from Lokroi on the South Italian coast.[196]

Like horses, the winds of Greek mythology have experience in transporting gods and the dead to heaven.[197] A wind is, of course, the most natural agent to snatch a curl. Thus, the bold, partly self-contradictory combination of imagery may appear less forbidding. To sum up: (a) Rider and horse are inseparable, and specifically, (b) horses were believed to have transported mortal beings to heaven; moreover (c) the winds were known to have done the same and, in particular, (d) the wind is the most natural agent to snatch a curl and, in the case of Berenike's lock, may even have done so. Thus, combining these elements, Kallimachos might have taken the liberty of letting the horse stand in for the rider and act as the gust of wind that carried the lock away.[198] In the third century, this image of the wind-horse will reappear (but see n. 191).

The mythical examples and religious beliefs about horses and winds converge upon each other: under both images, the catasterism of the lock appears as death, a point which was not lost on Catullus (51f. mea rata sorores/lugebant ). To this we shall return.

The lock continues his report (59ff.). The wind, after all, had only to transport him to the sea; from there he rose with the other stars to his place in heaven,[199] presumably at the heliacal rising so that Konon would notice the new lights. The belief that the dead become stars, or live on stars, is both Egyptian and Greek. The lock, however, does not enjoy, or at least claims not to enjoy, his new status and returns to his complaints (69f.). The passage is very fragmentary, but it is clear that, within his

[195] F. Cumont, Recherches sur le symbolisme funéraire des Romains , Service des Antiquités (en Syrie et au Liban), Bibl. arch. et hist. 35 (Paris, 1942), 502f. addendum to p. 149; cf. the same set of ideas in Gaul, ibid., 505, addendum to p. 218 (a woman galloping to heaven).

[196] There was a friendly relationship between Syracuse and Alexandria during the reign of Hieron II over Sicily and of Philadelphos and Euergetes over Egypt. See H. Hauben, "Arsinoé II et la politique extérieure," in Egypt and the Hellenistic World , 99-127, esp. 103.

[198] Cf. Marinone, Berenice , 197f. On the basis of Zwierlein's interpretation of the catasterism (n. 184) one could also argue that Kallimachos may have conflated what happened on earth (transportation of the lock to the temple of Arsinoe Aphrodite on horseback or in a chariot) and what happened on the divine level (Zephyr snatching the lock and bringing it to the same temple).

report, the lock now addresses Nemesis when he takes up his new position among the stars (71ff.):

[Be not] angry, [Rhamnousian Virgo (sc., Nemesis)! No] bull (i.e., the proverbial heavy weight that blocks the tongue) will hinder my word [. . . not even if] the other stars [tear my] insolence to shreds, limb [by limb]. . . . Things here give me not as much delight as distress because I no longer touch your head whence, when the queen was still a virgin, I drank much plain oil, yet I had not the pleasure of the lush ointments of married women. You, Queen, when, on the festival's days, you look at the stars and propitiate divine Aphrodite, you may not leave me, your own hair, without ointment, but rather give me large tributes.[200]

The personification of the lock as a constellation of stars, and his bravery in facing "dismemberment of his insolence" for speaking the truth, is hilarious in the extreme, all the more so if we recall the Egyptian beliefs behind it.  (if this is what Kallimachos wrote) is a metaphor similar to Plutarch's

(if this is what Kallimachos wrote) is a metaphor similar to Plutarch's  (Mor . 767E), and Catullus translates it correctly.[201] Yet the reader familiar with Egyptian thought is reminded that, according to Egyptian beliefs, the dead were threatened with being cut into pieces;[202] and, in a court of law, they had to confess their deeds and omissions. Such "negative confessions" became an oath which the priests of Isis swore at their initiation. In the new context, the negative confession was mixed with promises of what the new priest would not do.[203] Our lock has already sworn by the queen

(Mor . 767E), and Catullus translates it correctly.[201] Yet the reader familiar with Egyptian thought is reminded that, according to Egyptian beliefs, the dead were threatened with being cut into pieces;[202] and, in a court of law, they had to confess their deeds and omissions. Such "negative confessions" became an oath which the priests of Isis swore at their initiation. In the new context, the negative confession was mixed with promises of what the new priest would not do.[203] Our lock has already sworn by the queen

[201] 73: nec si me infestis discerpent sidera dictis .

[202] Zandee, Death , esp. 16f.

[203] PGM 2. XXXVII (Greek Magical Papyri , p. 278; M. Totti, Ausgewählte Texte der Isisund Sarapisreligion , Subsidia Epigraphica 12 [Hildesheim, 1985], no. 10) and R. Merkelbach, "Ein ägyptischer Priestereid," ZPE 2 (1968): 7-30 (reedited as P. Wash. Univ . II.71 by K. Maresch and Z. M. Packman, also Totti no. 9); further see Merkelbach, "Fragment eines satirischen Romans: Aufforderung zur Beichte," ZPE 11 (1973): 81-87 (edited as P Oxy . 42.3010 by P. Parsons). J. Quaegebeur considers whether the initiation oath discussed here is a fragment of the hieratikos nomos Semnuthi (i.e., the dm'-ntr[*] or "holy book"; cf. Merkelbach, "Priestereid," 11f.), a collection of laws which were of importance for priests ("'Loi sacrée' dans l'Égypte gréco-romaine," AncSoc 11/12 [1980/81]: 227-240, esp. 235f.). The motif was taken up by Roman poets; see L. Koenen, "Egyptian Influences in Tibullus," ICS 1 (1976): 127-159, esp. 129, and "Die Unschuldsbeteuerungen des Priestereides und die römische Elegie" ZPE 2 (1968): 31-38; W. D. Lebek, "Drei lateinische Hexameterinschriften," ZPE 20 (1976): 167-177, esp. 174ff.; O. Raith, "Unschuldsbeteuerung und Sündenbekenntnis im Gebet des Enkolp an Priap," StudClass 13 (1971): 109-125. An echo of the negative confessions of the oath of the Isis priests also survived among Egyptian monks: Hist. monach . 11.6 Festugière (see Merkelbach, "Altägyptische Vorstellungen," 339-342 and above, n. 42). Cf. n. 217.

that he did not commit a sin: invita . . . cessi, invita (38f.). He has now taken his position among the constellations of Virgo, Leo, and Callisto, and before Boötes.[204] In Hellenistic times, all these stars were connected with Isis and her myths. The constellation of Virgo was identified with her; and this constellation was also called Dike or Iustitia .[205] In short, appearing at his new place, the lock addresses the heavenly Virgin or Nemesis/Isis (alias Aphrodite) and, in accordance with Egyptian ideas, promises: "I will not be silent," "I will not enjoy my new life," both confessions contrary to what should be expected from the pious, but reflecting the locks anger and anticipating his destructive mood (see below). But the next confession turns back to his past: "I have not drunk the lush ointments (the perfumes) of married women." At the beginning of his new life as star, our lock behaves according to the Egyptian ideas of initiation, but in his emotional turmoil he turns part of them upside down. This is certainly funny, but in the overall context of this poem Kallimachos should not be misunderstood as taking a low shot at Egyptian ideas.

There is one more aspect to the lock's confession. He did not receive lush ointments when Berenike was not yet married. In the fifth Hymn Kallimachos presents Athene as an athlete running the double course like the Lacedaemonian stars (the Dioskouroi) and "rubbing in plain olive oil."[206] The crucial word for "plain,"  , is again rather prosaic

, is again rather prosaic

[204] See the map in Marinone, Berenice , 41.

[205] Merkelbach, "Erigone," esp. 483; see also L. Koenen, "Der brennende Horusknabe," CE 37 (1962): 167-174.

and in literature a latecomer.[207] This fact makes the use of the word even more significant. Thus Berenike, for as long as she is not married, seems to behave like Athene; now, as a married woman, she is rather like Aphrodite. On one level, this is an urbane and surely welcome compliment on her chastity;[208] on another level, the comparison of Berenike's behavior with that of the deities may constitute, from the Greek point of view, a claim for Berenike's deification; both before and after her marriage, she has done, and continues to do, what a goddess has done. But this also supports his claim to worship according to the Egyptian point of view: she plays the role of the goddesses.[209]

There remains an ambiguity. The phrase "I had not the pleasure of the lush ointments of married women" may refer either to the time when Berenike was unmarried or to the time after the marriage.[210] If the sentence is taken in the latter sense, the queen will only have changed her way of life and turned to lush ointments after her husband had returned from the war. Admittedly, during her husband's absence in the war she would not have had any use for myrrh. But not even the wedding would have given the lock an opportunity to taste real perfume.[211] The lock can hardly mean this. Hence, we return to the other interpretation: The lock complains that he received plenty of plain oil but no myrrh when Berenike was unmarried. He chooses not to speak about the time between the queens wedding and her husband's return from war, when the lock was sacrificed. In terms of historical time, this is a period of one and a half years; and her husband was probably at home during the first half

[208] For the sexual connotations of the use of myrrh, in contrast to the virgin's use of plain olive oil, see now L. Holmes, "Myrrh and Unguents in the Coma Berenices," CPh 87 (1992): 47-50. Also cf. n. 163.

[209] The argument presumes that the Lock of Berenike was written after the fifth Hymn , and this would date the hymn before 245 BC . The similarity between the two passages seems to establish some relationship between the two poems. I do not see much point in having the hymn refer to the Lock ; but it is possible that the idea of young athletic women using plain oil had caught Kallimachos' attention and he mentioned it in two places without intending to create an allusion. Athletes, of course, used plain oil, but they were men. For the date of the fifth Hymn see Bulloch, Fifth Hymn , 38-43 (Bulloch does not discuss the passage, but he notes the parallel).

[210] On the ambiguity of this passage see Herter, "Haaröle."

[211] H. Herter was worried about this problem but acquiesced by having Berenike just behaving like this. "Aber seit wir das Original haben, müssen wir uns damit zufrieden geben, dass die schöne Königin sich im Brautstande doch nicht gleich zu zahmeren Sitten bekehrt hatte. Oder sollte die Locke dem Hofpoeten falsch berichtet haben?" ("Haarö1e," 68; repr., 206).

of the year. The lock surely had a rhetorical interest in not mentioning the few happy months, when he experienced the myrrh on the queen's head among his sister hairs. But what interest did Kallimachos have in the lock's oblivion?

Greeks performed the sacrifice of hair both as a pledge and as a nuptial rite.[212] Arsinoe III is celebrated in an epigram by Damagetos as having sacrificed a lock at her wedding to Philopator.[213] In our lock's mind the two events, wedding and pledge, are merged (see above). There may be, just may be, a further merger. Hellenistic Egyptians cut their hair also in the mourning for Isis, as did Erigone in her mourning for Ikarios, presumably in Eratosthenes' Erigone .[214] This ritual of mourning is, of course, different from a votive sacrifice of locks,[215] but the fact that Kallimachos sees the sacrifice under the metaphor of death may indicate that he blurs the distinctions. A terracotta piece, originally part of a vessel, seems to show Isis pulling out her hair. It has reasonably been argued that this Isis figure should be explained in the tradition of the royal oinochoai . Thus, it would most likely represent Isis as enacted either by Arsinoe III or Kleopatra I.[216] Berenike may have done just the same. Her "mother" Arsinoe was worshiped as Isis.

The claim (and at the same time confession—see above) that the lock never had the pleasure of real ointments may be carried one step further. The longing of the sister hairs for the lock and of the lock for perfumes may have a sexual connotation too. As long as the lock was on the queen's head and neither he nor his sister hairs received perfumes, he had no opportunity to enjoy sex.[217] But if we are indeed expected to perceive a flash of such connotations in the lock's claim, then they remain in the background, more in the reader's fantasy than in what the lock tells us.

[212] See Nachtergael, "Bérénice II."

[214] Merkelbach, "Erigone."

[215] To this extent I agree with G. Nachtergael, "Bérénice II," also idem, "La chevelure d'Isis," AC 50 (1981): 584-606.

[216] D. B. Thompson in Eikones (dedicated to H. Jucker), ed. R. A. Stucky, I. Jucker, and T. Gelzer, Antike Kunst, Beiheft 12 (Bern, 1980), 181-184.

The lock proceeds to request his share when Berenike worships her "mother" Aphrodite-Arsinoe (diva Venus ) on her festivals. These include the Arsinoeia. He asks for "libations" of myrrh. Since this request is an aition , we may conclude that offerings of myrrh played a part in the real world of the festivals of Aphrodite-Arsinoe. In technical terminology, "libations" of myrrh or ointments fall under the broad category of "offerings of oil"  . The little that is known about libations of oil in Greek cults seems to indicate that these offerings were connected not only with the cults of deities but also with those of the dead. Libations of wine to the dead, specifically to the deified queens, are known to have been part of the Alexandrian cults, including the Arsinoeia.[218] The offering of myrrh by Berenike to her deified mother, the new Aphrodite, fits this mold, and so would the same offerings to the constellation of

. The little that is known about libations of oil in Greek cults seems to indicate that these offerings were connected not only with the cults of deities but also with those of the dead. Libations of wine to the dead, specifically to the deified queens, are known to have been part of the Alexandrian cults, including the Arsinoeia.[218] The offering of myrrh by Berenike to her deified mother, the new Aphrodite, fits this mold, and so would the same offerings to the constellation of  if, indeed, such a cult was established. The lock, too, is deceased and resurrected, and thus entitled to a hero's offerings. But, of course, the rather somber background disappears both in the joyful celebration of the real festivals and in the hilarious situation in Kallimachos' poem, in which a simple lock, cut from the head of his queen, asks for the stuff that he missed most in his lifetime, and in which a queen offers the myrrh to what once was her own curl! Kallimachos felt that myrrh was the appropriate gift for the lock. Once again, his banter entertains his royal reader as well as his general audience.

if, indeed, such a cult was established. The lock, too, is deceased and resurrected, and thus entitled to a hero's offerings. But, of course, the rather somber background disappears both in the joyful celebration of the real festivals and in the hilarious situation in Kallimachos' poem, in which a simple lock, cut from the head of his queen, asks for the stuff that he missed most in his lifetime, and in which a queen offers the myrrh to what once was her own curl! Kallimachos felt that myrrh was the appropriate gift for the lock. Once again, his banter entertains his royal reader as well as his general audience.

The partly hopeful and serene, and partly entertaining, image of the queen raising her eyes to the stars while also giving libations of oil to her lock is abruptly ended by the lock's final outburst: may the stars perish, and may Aquarius and Orion—two constellations far apart from each other—shine beside each other, that is, may the starry sky collapse, if only he could reside on the head of the queen.[219] Such feelings are genu-