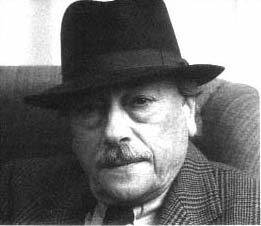

Jean-Jacques Viton

Jean-Jacques Viton was born in Marseille in 1933. With Liliane Giraudon he cofounded Banana Split , which became La Revue vocale: La Nouvelle BS in 1990 and which he and Giraudon still codirect. He has published Au bord des yeux (Paris: Action poétique, 1963), Image d'une place pour le requiem de Gabriel Fauré (Paris: La Répétition, 1979), Terminal (Paris: Hachette-Littérature/P.O.L., 1981), Le Wood (Paris: Orange Export, Ltd., 1983), Douze Apparitions calmes de nus et leur suite, Qu'elles provoquent (Paris: P.O.L., 1984), Décollage (P.O.L., 1986), Galas (Marseille: Ryoan-Ji, 1989), Episodes (P.O.L., 1990), and L'Année du serpent (P.O.L., 1992). He has also translated, with Liliane Giraudon, Nanni Balestrini's Cieili (Turin: Tam-Tam, 1984) and, with Sidney Lévy, Michael Palmer's Notes pour Echo Lake (Marseille: Spectres familiers, 1992).

Selected Publication in English:

"Fractured Whole." Translated by Harry Mathews. In Violence of the White Page: Contemporary French Poetry , edited by Stacy Doris, Phillip Foss, and Emmanuel Hocquard. Special issue of Tyuonyi , no. 9/10 (1991): 213–17.

Serge Gavronsky: Poets and writers were talking about écriture before Jacques Derrida, but at a certain moment that term undeniably became a philosophic one, an idea unto itself, separate from content and, in a way, forming a content by itself; that is, écriture played on a passion which had been Mallarmé's, perhaps, but was especially that of the Russian Formalists, Tel Quel , and Change . One might even say that some of the younger poets have accepted that idea, particularly the more sensitive ones who seem to assume that to be a poet means—and can only mean—to suffer the theme of absence, negation, the void, that is, to take metaphysics as a subject and, as a way of reaching it, to exploit language per se: to write about writing, a metapoetic enterprise. This came to characterize experimental French poetics and perhaps too played havoc with the possible expression of talents that existed in a country where poetry may be considered the ultimate pursuit of language, the proof of one's nobility in literature. Too many individuals were ambushed along the way to their discovery of poetry by this THING that became what can only be considered a school of poetics. It doesn't have -ism as a suffix, but it still has magazines from Marseille to Paris, small presses, and at times even the support of major publishers like Mercure de France, Seuil, or Gallimard, as well as, in the earlier days, Flammarion. I wouldn't call it formalism, because that would be too limiting, but this focusing on the "self" of language has to be seen as one of its major traits. I suspect you see what I'm leading to . . . And now, with complete freedom to change the subject, move in another direction, or stick to this rather sticky question, I wonder if you might not comment on your own place in this language locus, in this philo-metaphysical reading of the place and significance of language in your own work?

Jean-Jacques Viton: The question you ask and the manner in which you've formulated it already contain the basis for the answers that now must be given—which is most convenient! At one point you used as an example those individuals about whom one might have said, without reservation, that they threw themselves into a form of writing that appeared to pursue the idea of écriture, even as they went

beyond that idea in their works. I would call that a constant sidetracking of écriture itself in its relation to the person writing. You spoke of a school, a fashion; you're right. There was then an unquestionable preoccupation that rendered the work of a writer opaque. Opaque because we were writing at a time when, I wouldn't say things were easy, but when we had no doubt disengaged ourselves from innumerable traps that, for the last fifteen or twenty years or thereabouts, writers had encountered, had themselves sown, reaped, and sown once more, and so on. Thence a type of activity, pleasurable enough, in which a ruffle of questions appeared in the guise of answers, answers wanting to be questions, as Barthes would have put it.

Well, then, can it be said that this concern for écriture—for écriture as a concept unto itself, in texts that move forward by perpetually going over their own projects, as we were saying—can it be said today that this constitutes a true obstacle? I believe that nothing constitutes an obstacle. Everything nourishes a scriptural enterprise. As for myself, I'm not one who was particularly involved, though I was involved, to the extent that everyone else was, at the level of an ambience, of—how should I put it?—a logic, quasi-biological in its preoccupation. But I've never been able to be, nor have I wanted to be, a theoretician of écriture. Through this preoccupation—which was more than a mere preoccupation; I would say that even among those who took themselves as representatives of this theory, there was a belief . . . a need to illustrate it with an image of danger . . . Just as people said in 1793, "The Nation Is in Danger," so these individuals suggested that "écriture is in danger." What followed was a kind of Committee of Public Safety for écriture, which completely terrorized/theorized the world of letters.

Paradoxically, these things, that period, served as a sifter, a filter, whether consciously or not, and now we find ourselves facing something that's—I don't want to imply "lighter," but a type of release, even in its gestural nature. We have turned a corner. I can't define it better: a sort of trial or test, similar to those trials in the romances of the Round Table—as if we were crossing through such an epoch

and had now passed beyond those obstacles. They were the trials. That's how I see it. What I find if not amusing, then at least curious, is that when you study these trajectories of a writer and try to situate them, there is a pre- and a post-Tel Quel period. You discover people in the pre-Tel Quel mode who had said . . . First of all, let's say they were very young, and let's say, too, they were at the beginning of their careers, careers they chose because literature interested them, not writing about literature or écriture. Then this great passage ensued, this great trial, and one discovered that for these people—not that they were doing the same thing over again—it was as if there had been something between the axis of departure and the axis of their current position that tended to connect the two. Nevertheless, one can say that they were nourished by this passage and, as a consequence, these experiences. They were enriched by them. I can't find a better word for it.

SG: May I follow through with a more precise question? You alluded to the concept of a passage, and you yourself participated in the activity of that period (the Tel-Quelian one) as a member of at least two very important literary magazines coming out of Marseille. The first was Manteïa , which at the time I considered rather Stalinian in its efforts to model itself on Parisian theories; the second, much more recently, is Banana Split , which you cofounded and codirected with Liliane Giraudon, and in which, once again, taste is being defined through a selection of artworks, lots of translations, and of course a strong sample of what is being written in France today. In both instances, there seems to have been a strong ideological position, one which you have never failed to state categorically . . .

JJV: Let me add to that list a third magazine . . .

SG: Have I forgotten Cahiers du Sud ?

JJV: In that case, I'd add still another one! And I do this not to figure in some hit-parade list of magazines, but to provide information about those to which I belonged. I actually began with Action poétique . During the Algerian War, this magazine was defined by its strong political commitments, its social views that represented many of us, especially

those who belonged to the editorial board. It was a militant magazine in the negative sense of the word; that is to say, apart from the fact that we all belonged to organizations dedicated to social struggle, Action poétique felt obliged—in a sort of continuity with post—World War II beliefs?—to evoke, in terms of images, the experience and the reflections of militant action. Then followed Cahiers du Sud , which, as everyone knows, was based in Marseille. It was the first magazine characteristic of a certain decentralization in France, the first to publish people who had not yet been published elsewhere:Barthes, Neruda, Saint-John Perse. No one had ever published them before. Later on, with a group of friends, we founded Manteïa , for which Cahiers du Sud published the first masthead—not a good sign! In the end it did find acceptance.

As you can see, that was the beginning: Action poétique , where writing was something organic, poetry mixed with a militant endeavor in its distribution and sales. Cahiers du Sud was a literary coterie that made us think we knew how to write or were bothered by the fact that we wrote . . . I don't know. Manteïa followed. That was something else! We wanted to launch something in reaction against both Action poétique and, to a certain extent, Cahiers du Sud , which had cast an overly fraternal glance in the direction of Manteïa —and you're right, what you said about that particular effort was true! But I could just as easily mention other magazines that found themselves in the same boat, alluding to your formula of being more Tel-Quelian than Tel Quel itself! Still, we cut our teeth on modernity at Manteïa . We learned to think collectively on texts that were the so-called classics, which we resituated in a temporal reading, within the scope of our own readings, and without a doubt, we learned how to make a distinction between the repositioning of the text and what might have been considered the "organic" desire expressed by the writer. This period, a very interesting one, was nearly obliterated by Tel Quel , most assuredly! But as I said a moment ago, it was also quite obviously enriched by this type of important movement that was taking place in France at that time.

That sums up three experiences that led to the creation of Banana Split . Liliane Giraudon participated in Action poétique as well, after I had left it, though she never had any contact with either Manteïa or Cahiers du Sud . When we found each other, we wanted to do something fundamentally different from what had been done previously. We wanted to get away from the institutionalized look that characterized Cahiers du Sud as well as from a dose of militancy, media, and that breathlessness that typified Action poétique . We wanted to get away, too, from a form of theoretical obeisance, or rather postural, in line with Tel Quel —that is, to define a breach with respect to Manteïa itself. We were especially interested in doing something that would disengage us from other committees, the blight of other reviews—that is, those editorial boards with their fifteen members, only one or two of whom actually made the decisions, and in which there are frightful internal struggles—all that is anecdotal because it's unbearable! We wanted to do something by ourselves. It was a couple's adventure! And why did we pick the name Banana Split ? Because we wanted to break with and set up an opposition to all those things I just mentioned. The title of the magazine was at once the most ridiculous and the best known throughout the world, and, put simply, it amused us both!

One important aspect of BS is that, unlike other magazines in which both of us have participated, we were not going to publish ourselves; that seems to me very significant, since it allowed for a certain disengagement in the way we looked at the magazine. You'll find translations and interviews in BS but no critical texts, and that we also felt was different. In terms of material presentation, there's no other magazine like ours, with its inexpensive mode of production: the contributor either types out or draws his or her own work on 8 1/2-by-11-inch paper, and then these are photo-offset. Because of this impoverished look, we took extreme care in the selection and the composition of the contents, which we thought out in light of a permanent commitment to internationalism; there was usually a bilingual presentation, with translations by people who were themselves writ-

ers and poets, serious people with a worldwide reputation. This is not so with other publications, which often publish translations but not in the same spirit. Things don't come together elsewhere the way they do for BS !

SG: And your own work? You have been a militant journalist in Marseille, a theater critic, a poet, and a novelist published by one of the most prestigious houses, that is, P.O.L. In fact you seem to have worked out all possibilities in the world of writing. When you reread yourself, the work you have done over the past many years, is there a way of identifying particular moments, types of écritures that have characterized your own work, and specifically something which is not overly fashionable these days, that is, the presence of the subject, the subject as it has been conceptualized by Lacan and specifically exorcised by him, in fact expulsed from the matter of discourse? How would you establish a relationship between écriture and content, subject and narration?

JJV: That appears to reconnect with elements of your first question, that is, a type of trajectory and the idea of a passage. I said I found it surprising that there were people who were more or less in the same position before that great period marked by Tel Quel and were obviously transformed by it thereafter, as I was. I'm talking about a real transformation. Up to 1986, roughly, I continued to write with a certain distance in mind between what I was writing and how I was writing it; I'm thinking of Terminal and Douze Apparitions calmes de nus . At the same time I became aware that, while proceeding on that course, I had succeeded in building something that now appears to me quite significant, something that, far from bringing me closer to others, from "communicating," to use a current expression, instead— I don't know how to express it—increasingly, and with greater and greater distinctiveness, cut me off from something I didn't want to belong to in any case, that is, a general exteriority of discourse, which I tend to dislike more and more.

I became aware that I was reworking this ambition, this construction in another work, Décollage . There, with an even greater preci-

sion, I was rediscovering old tracks that were still there, ones I had laid down a good while before Action poétique , at the time when I was beginning to write. But with this practical experience and with these collages, I became aware that I was placing myself in the text, and that was something I hadn't done before! First of all, this was not the way to arrive at taking the self as a subject, and second, on a more trivial level, at that time it wasn't being done. I became aware that this was the very thing that allowed me to build a sort of wall, a wall of separation. When I placed myself within the text, that wall took shape, so to speak. If I continue to write, it's in that vein—or at least that's what I sell! As you know, I'm not at all ashamed of putting myself on stage when I'm in the process of writing.

SG: For the past few years, let's say since the end of the seventies, there has been a movement toward what some call a new lyricism, an expression I use with all possible reserve. From an American point of view, especially in the shadow of the Beats, this doesn't seem to be a real issue. Lyricism in poetry—and I'd say that as much for traditional French poetry as I would for American poetry (in its dependency on the narrative, on personal experiences)—has always been central. That it should now appear in France in "difficult" texts like yours and Giraudon's is indicative of a reappraisal of what had once been ideologically taboo in the kingdom of écriture! And now there is a return, especially among younger writers, to the autobiographical, whether in homosexual narrations such as Mathieu Lindon's or the coming-to-consciousness of the feminine-feminist positions, most evident in the publications of Les Editions des Femmes. From my readings of these new texts, the body once again occupies center stage as a bio/graphic exercise.

Today, are we seeing a cultural interference, whereby the I in your own work reflects a more general current? In your evolution, might there be a rejection of "theory" in favor of the subject, the speaking subject, that is? And if that's a correct reading of recent literary events, would you talk about the concept of distanciation that characterized your écriture during the years 1960–75, and perhaps even

later? Or, put another way, can what is now being written be "readable" for you in terms of your own perception of the text?

JJV: I'm glad you asked that question, but let me go back to your initial word, lyricism. I think that in the case of lyricism in the U.S., there's always been a positive reaction, as you correctly noted—and you know more about that than I do. Today we're witnessing a worldwide trend, about which we should be asking certain questions! Or might it simply be a matter of the circulation of information? I'm not quite sure how to put it, but perhaps there is an affective element that crosses through, that moves like something living within the general body, which would be the world. It's surprising to observe this coming-and-going, this sort of voyage underway, but I believe that is happening in France. Today there are books and shows that seem to discover that things have an expression, a form of expression which, when I began writing, I had been warned against. I find this current absolutely distressing.

SG: In a paradoxical manner, I wonder if the presentation of the Beat poets in France hasn't, in the long run, had a negative influence on French readers? When we talk about poetry in France, we are actually referring to a few, very few sensitive souls—to go "romantic" for a moment—who might have discovered in those texts you published, and others that followed yours, a way of being that was otherwise censured by a poetic consensus. Might we not see in what's happening today a kind of dialectics of poetics at work here, that is, an antithesis working behind the scenes during those years which eventually would have an impact on mainstream works of the experimental school? Some of these recent autobiographical writers may be reaping the rewards of a steady American fifth column! Now they're finally legitimizing what they always wanted to do but were afraid of doing, given the existing constrictions.

JJV: I know what you're getting at! I won't name names, but let me go back to what I was saying when you were first discussing lyricism. There is indeed a new battle cry that goes by the name of lyricism. But it's a lyricism that has been contracted for. I can only speak about

poetry through my own personal experience, which is the only important one, as concerns myself. What kicked things off for me, what acted as a catalyst, was this unconscious preparatory work. As if there had been a storehouse in which such things had been placed, leading to the discovery of new texts, of new forms of expression, uncovering various changes residing in the interior of the poem. After that came all the adventures I mentioned earlier. What I now find is a freedom in my way of reading, and I find—I'm tempted to say that old spark, but obviously it comes with other elements that I now place within the poem, elements I would attribute to particular events but that are also partly the result of age, of my experiences. These are constantly seized on a daily basis. That's how it is for me. I often have the impression, reading other texts, that there must be a reaction one might qualify as lyrical but within which one can ultimately discover aspects not too distantly related to that earlier, epochal period. So that in the end, I continue to see a tale of masks which continues to play itself out.

SG: With everything we've just said, wouldn't it seem that to be a poet or a writer is, to a large extent, not uniquely determined by personal options? Can it be said, and particularly in France, that liberty of expression is readjusted according to the period's diktats, which are most effective when they are interiorized, and not necessarily when they are openly suggested and tyrannically enforced? This condition of being, to borrow a term from metaphysicians, seems to me extremely difficult for poetry, for that ideologically based poetry to which we were alluding. Everything we've been saying seems to reinscribe écriture within a framework. Would you consider this overshadowing of écriture by ideology a "good" thing? Has it affected your own work as a novelist, as a poet?

JJV: I don't understand what you mean when you speak of diktats. Are they implicit ones?

SG: Yes, which makes them all the more influential—for instance, the presence of Heidegger in contemporary French philosophy and the incorporation of this philosophy within poetic discourse, into critical writing about poetry. This doubling of the creative act seems to me

one of the fundamental characteristics of both the writing of poetry and the writing about poetry in France today. They are overdetermined by a philosophical argument, itself closely allied to what is being done in poetry at this very moment. Poetry is never by itself. It always appears to travel alongside works of the mind, and these works of contemporary philosophers or belletrists not only provide a vocabulary allowing for the discussion of poetic works but influence poetry itself.

JJV: I too believe that such things go on. It's as if you asked me, in the final analysis, whether life played a part in determining the nature of écriture. Well, yes, of course it does, but I don't believe at all that today either the writer or the poet—but let's limit it to poetry—is one who in any way holds the truth, points the way. I don't believe that at all. On the other hand, I absolutely believe that writing is a calamity. It doesn't come out with any messages, and that's why, in my own case, I'm constructing something that increasingly, and with growing success, separates me from the outside world, which, to tell the truth, I have no desire to frequent. Some writers may be subject to a number of influences—their readings, their books, their work conditions, their social milieu, what happens in the world—all that is quite evident, but I personally do not believe we're here to render an account of this type of event; I'm not, in any case.

SG: I suspect some of the newer tendencies in American poetry might concur with what you've just said, especially Language poets, who are, like any group of gifted poets, more interesting in their own specificity than as representatives of a school. But I would think that the position you've defined for yourself might clarify the proper area of poetry, of the production of poetry, one that is clearly closer to my own definition of écriture as it's being practiced in France than to a poetics of commitment or the transcription of everyday life, even into its poetic forms. The distance you've described may actually be liberating, allowing you to emphasize, outside the arena of polemics, a nonprophetic vision, a nondemagogic one, too; from this particular point of view, I believe the French influence may prove a positive one

in the U.S.—at least, of course, in certain receptive milieus. In the years to come, as you continue publishing contemporary American poetry and organizing readings in Marseille and elsewhere, it will be interesting to note if indeed an implicit American influence is discernible in French poetry.

How would you like to conclude this conversation?

JJV: With this observation: One might also simply ask why one writes. To which I would say, not so as to act as a witness for our time, and if not to point the way, to signal something, then certainly not to become the echo of what is happening in society. The answer is that only poetry can answer why we write. For someone who wants to write, it is the only means of writing: poetry, and nothing else.

Don't Forget to Write to Aunt Augusta

a moment ago in the kitchen I devoured

two servings of a veal sauté with carrots

smothered in black pepper and a chili sauce

at home we're decidedly up on everything that's hot

I drank three glasses of an excellent Luberon red

followed a while later by a chilled bottle of Belgian beer

it hadn't rained for a long time and tonight

it's coming down heavy I hope you're not cold

in your quaint little house where when we arrive

we share with you some quince jelly

don't forget to go to the garden and pick

the last fruits left on the trees

be careful and use the long rake

I want to tell you

these days I'm living like a lunatic

on my paper the ink overruns the letters

like a lunatic has become like a tick

I have to correct the words

but I believe that lunatic and tick

in this situation of the mind and the body

can really help each other mutually

lunatic and tick are noble words

they grab your attention

they grip onto the subject

lunatic and tick both captivate in the same sudden manner

they force you to step back

the same attraction

you're probably thinking

he loves like a lunatic and lives like a tick

in neither case is that acceptable

I shall therefore tell you about a word sauté

you'll find this association rather lighthearted

I know you'll mention it to me one day

a little critical at once

meaningful as a general feeling

disagreeable for evening wear

disturbing for the narrative movement

but authorizing irreplaceable round trips

if I tell you

how much I relish a veal sauté

it's because you give me the chance right here

to satisfy a very old desire

begun while reading late at night in bed

the adventures of tom sawyer and

the adventures of tom playfair and then

the deerslayer and then jack london

it became definite as I read steinbeck

and a certain number of other authors

in whose works apple pie or

rhubarb pie which I don't like as much

occupies a place of importance and often repeated

not so much in its alimentary role as

in the words employed to describe it

now it's my turn I can use

the word portion I always read a hefty portion

the word serving I always read two large servings

and so let me tell you

that old desire has been satisfied

antonia she too can whip up

a wicked pear pie

she places the pies on the windowsill

you can see them going by her place

on the road that goes down to the bridge

the fruit pies are outside

the tomato jars inside

you know that this system is defined

at the heart of a wordless story

where time spent in a cave

cannot resemble the time spent

in putting up a log fence

when antonia was a young woman

albert césar and vincent made

everyone dance in the neighboring villages

the three of them were accordionists

césar was also a shoemaker he made

work shoes and going-out shoes

he bought the uppers in town

had the leather delivered to his shop

his shoes were solid and handsome

all three are now dead

antonia is the only one left who still talks about them

but she prefers to tell you how

she slit off with her knife

twenty fat slugs on her staircase

how she climbed up the mountain

to go to school holding the tail

of the donkey that her mother the teacher

led by the bridle

a teacher pulling a donkey

pulling a child going to class

what a fabulous living chain

it shows how a little girl

finally learned how to read

when I write little girl

you should be able to gauge through the paper

what emotion I feel at this moment

it pushes me off the chair I'm sitting in

perhaps this particular distress which travels

so perfectly so perfectly useless

will reach your fingers

I wonder what would be left for me to talk about

if I were in antonia's shoes

if I received friends insisting

they be told something

what could I tell them

that might have the weight of a nicely told story

with clearly interconnected links

I don't know

my life's skin like everyone else's

is emphatically marked by pithy epic episodes

without any true connections between them

that rise and then fall to the ground

like lead soldiers with broken bases

it is built up of things that cannot be placed

by those who listen in to biographies

a sequence of tiny tales slightly tufted

only remembered in one's image memory

by a twist of the mouth articulating them

a twist of the mouth first of all and then

a twist of the memory and of its fat

a sequence held together by quotes

angling on different paths

in the direction of misunderstanding and doubt

I've long been moving

on this sonorous page with its narrow squares

in the absurd dignity of a locomotive

pulling freight cars with

bags of texts of different sorts

a train carrying various bits of information

that all work in a similar manner

seals eaten up by bears on icebanks

shoes belonging to egyptian soldiers

in the streets of Port Fuad in 1956

graffiti on the walls of barracks

in the Camp des Milles where the Vichy government

locked up thousands of foreigners in trouble

before turning them over to nazi officials

that Milles Camp near Aix-en-Provence where

the bourgeoisie thrilled by Solidarity

lit up exotic candles on their windowsills

when Jaruzelski's Poland declared a state of emergency

Aix-en-Provence where the bakers downtown

still refuse to serve gypsies

and so forth

all those frightful boxcars whose roofs

must be clamped down and the tarpaulin laced

before the train can leave

it's written on the doors

one day in one of the streets of that city

in front of two raven witnesses

squeezed on the branch of a sick plane tree

like numbers on a scoreboard

an account of time was carefully inscribed

let there be gongs whistles and stridencies

a repetitive injunction

in order to forestall forgetfulness

the tongue must give

eyes and ears must take

especially don't let them get lost

without mentally touching those pieces

torn out of a puzzle handed back to us

ask yourself listening to a young girl

who only stares through the place

of history recomposing itself

who knows where her eyes are shining

on that face rosier than roses

one day that young girl comes up to him

both of them sit down by the seashore

a shot of the sea and seagulls

pirouetting around them, zigzagging

she wants to know if he still loves her

she loves him and nobody else

he holds her in his arms and tells her

the whole story of his grief and

his desire for her and his love

I love you I love you he repeats

and as he leans over to kiss her

he discovers she's dead

for while telling her of his love

he had choked her in his arms

you see the young girl might

have made a simple movement

she didn't want to

it's inexpressible

how do you remember a gesture hardly begun

how does the body move

how does the body do it in this painting

of movements to be executed

how does it do it to get up to sit down

to pick up a pebble

head held high

it rests on the neck

the neck holds up the shoulders

the shoulders bring up the arms

in all of this planning of a fall

the point of the game is to keep one's balance

the stakes of this incomprehensible game

it's the force of gravity holding us

upright like a definitive door

I know of a far funnier game

the percussive movement in Ravel's bolero

you divide the repetitive sequence into four parts

first of all four raps on the drum that's I

then four raps plus two that's II

then the four raps come back and that's III

finally ten raps on the drum and that's IV

when you work it out on a kitchen table it comes out

pa pa pa pa

pa pa pa pa pa pa

pa pa pa pa

pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa pa

a bit tedious but very pretty

it's been going on for the last fifty years

easily transmissible and simpler

than the game of alternating colors

I look at a chair in my room

its back is formed of wooden rods

dark and light alternating I count eight of them

three blacks against a yellow backdrop

five yellows against a black backdrop

I'm having fun switching from

the lights to the darks

meaning changes every time

into its opposite

now I'm going to tell you

a chinese tale

once upon a time there was a chinese man and his wife who were

very poor

they lived in their hut by the banks of a river

they had a child and since they were very poor

they couldn't keep it

one night the man took the child

the moon was bright on the river

he threw it in the water

a year later they had another child

they were still very poor and couldn't keep it

one night the man went back to the river

and threw the child in the water

the moon was shining on the river

a year later they had a third child

they weren't as poor and so they kept it

when the child had grown some the father took him in to town

when they got back to the hut it was night

the moon was shining on the river

the child said: "look father at the beauty of the moon

shining on the river

just like on those two nights

when you drowned me"

it's a frightening tale

and splendid don't you agree

but don't water my ashes

with a useless poison

I'm a football said a friend staring

at his feet crossed together and his legs spread out

in front of him on the train

bringing us back from Royaumont

where on the greenish canals loaded with red leaves

no more swans go by Royaumont where

I had heard that the story of the harnessing

of forty bulls brought together

to knock down the high tower of the abbey

at the beginning of the french revolution

wasn't a true story that's just fine

most of the stories told about revolutions

put into circulation like that phenomenal harnessing

are inventions rumors shot full of holes

spread among the people

to shake them up to make things jump

that shouldn't be moved

but go on speak speak mouth

your lips form a long life

you were saying how to tell things

that didn't connect

I'm still laughing at your quizzical face

as the story unfolds

the surge of a new and solid crest

that empties itself and then disappears

behind the rising fog of darkness

what is commonly known as nightfall

falling in fact falling

in the oscillation of its feathers

and the kids' bath the tea table

tree shadows in front of the house all lit up

what a moment of passage dark and narrow

the abyss impossible to cross in a single leap

I haven't forgotten the least detail

of those stories I'm telling you

everything else you already know

but perhaps you've never noticed

at the movies when on the screen

the sidewalk is wet with rain

people in the theater move their feet under their seats

fearing they too might get wet

Ne Pas Oublier La Lettre à Tante Augusta

il y a un instant j'ai dévoré dans la cuisine

deux portions de sauté de veau aux carottes

recouvertes de poivre noir et de purée de harissa

nous avons ici un vif désir de tout ce qui est fort

j'ai bu trois verres de vin rouge du Lubéron excellent

et peu après une bouteille de bière belge fraîche

depuis longtemps il n'avait pas plu et ce soir

ça tombe serré j'espère que tu n'as pas froid

dans ta vieille petite maison où quand nous venons

nous partageons avec toi de la pâte de coing

n'oublie pas d'aller dans le jardin cueillir

les derniers fruits qui restent sur les arbres

fais attention et sers-toi du long râteau

je veux te dire

en ce moment je vis comme un fou

sur mon papier l'encre déborde les lettres

comme un fou est devenu comme un pou

je suis obligé de corriger les mots

mais je trouve que fou et pou

dans cette situation du corps et de l'esprit

peuvent bien s'aider mutuellement

fou et pou sont des mots nobles

ils accrochent l'attention

ils s'accrochent au sujet

fou et pou captivent de la même manière subite

ils provoquent le même recul

la même attirance

tu es en train de penser

il aime comme un fou et vit comme un pou

dans les deux cas ce n'est pas admissible

je vais donc te parler d'un sauté de mots

tu trouveras cette association un peu leste

je sais que tu m'expliqueras ça un jour

un genre de petit jugement à la fois

important pour le sentiment général

désagréable pour la tenue formelle

encombrant pour la conduite narrative

mais autorisant des aller retour irremplaçables

si je t'avoue

ma faiblesse pour le sauté de veau

c'est que tu m'offres ici l'occasion

de satisfaire un très vieux désir

commencé en lisant tard dans mon lit

«les aventures de tom sawyer» et

«les aventures de tom playfair» et puis

«le tueur de daims» et puis jack london

ça s'est précisé en lisant aussi steinbeck

et un certain nombre d'autres auteurs

chez lesquels la tarte aux pommes ou

la tarte à la rhubarbe que j'aime moins

tient une place importante et répétée

non pas dans son rôle alimentaire mais

dans les mots employés pour sa mise en scène

c'est mon tour maintenant je peux utiliser

le mot part je lisais toujours une grosse part

le mot portion je lisais toujours deux larges portions

ainsi je peux te le dire

le vieux désir est satisfait

antonia elle aussi sait faire

de fameuses tartes aux poires

elle les place sur le rebord de sa fenêtre

on les voit en passant devant sa maison

de la route qui descend jusqu'au pont

les tartes aux fruits sont à l'extérieur

les bocaux de tomates à l'intérieur

tu sais que cette organisation s'accomplit

au centre d'une histoire sans parole

où le temps passé dans une cave

ne peut ressembler au temps mis

à monter une grille de bûches

lorsqu'antonia était une jeune femme

albert césar et vincent faisaient danser

les villages de la commune

ils étaient tous les trois accordéonistes

césar était aussi cordonnier il fabriquait

les chaussures de travail et celles de sortie

il achetait les tiges en ville

se faisait livrer le cuir chez lui

ses chaussures étaient solides et belles

ils sont morts tous les trois

antonia est seule à parler encore d'eux

mais elle préfère raconter comment

elle a sectionné au couteau

vingt grosses limaces sur son escalier

comment elle grimpait dans la montagne

pour aller à son école en tenant la queue

de la mule que l'institutrice sa mère

conduisait par la bride

une enseignante qui tire une mule

qui tire un enfant qui va en classe

c'est une magnifique chaîne animée

elle indique comment une petite fille

a finalement appris à lire

lorsque j'écris petite fille

tu devrais percevoir à travers le papier

quelle émotion j'éprouve en cet instant

qui me bouscule du siège où je suis assis

peut-être que ce trouble exact qui voyage

tellement parfait tellement inusable

parviendra jusqu'à tes doigts

je me demande ce que j'aurais à raconter

si j'étais à la place d'antonia

si je recevais des personnes décidées

à se faire raconter quelque chose

qu'est-ce que je pourrais leur dire

qui aurait valeur de récit organisé

racontable de maillon en maillon

je ne sais pas

la peau de ma vie comme celle de chacun

est martelée par de petits épisodes épiques

sans réelle relation entre eux

qui surgissent puis tombent à terre

comme des cavaliers de plomb sans assise

elle est construite de choses non repérables

par les écouteurs de biographies

une suite d'historiettes aux aigrettes maigres

dont on ne retiendrait dans la mémoire des images

que la déformation de la bouche de qui les articule

déformation de la bouche d'abord et ensuite

déformation de la mémoire et de sa graisse

une suite qui tient par citations

fléchant sur des chemins divers

en direction du malentendu et du doute

je bouge depuis longtemps

sur cet étroit quadrillage sonore

dans une absurde dignité de locomotive

qui tire des wagons de marchandises

sacs de textes de nature différente

un convoi qui charrie des informations variables

mais d'un fonctionnement semblable

des phoques bouffés par des ours sur la banquise

des chaussures de soldats égyptiens

dans les rues de Port-Fouad en 1956

des graffitis sur des murs de baraquements

au Camp des Milles où le gouvernement de Vichy

enferma des milliers d'étrangers en difficulté

avant de les livrer aux fonctionnaires nazis

ce Camp des Milles près d'Aix-en-Provence où

la bourgeoisie frémissant pour Solidarité

alluma des bougies exotiques à ses fenêtres

quand la Pologne de Jaruzelski subit l'état d'urgence

Aix-en-Provence où les boulangers du centre-ville

refusent toujours de servir les gitans

et ainsi de suite

tous ces wagons consternants dont il faut

que le toit soit verrouillé et la bâche lacée

avant que le train ne parte

c'est écrit sur leur porte

un jour dans une rue de cette ville

devant deux corbeaux témoins

serrés sur leur branche de platane malade

comme des notations de boulier

le compte du temps s'est précisément inscrit

il faut des gongs des sifflets des stridences

une injonction répétitive

afin de prévenir l'oubli

il faut donner par la langue

prendre par les yeux et les oreilles

surtout ne pas laisser se perdre

sans les palper mentalement les pièces

déchiquetées du puzzle qu'on nous a remis

il faut se demander en écoutant une jeune fille

qui ne regarde qu'à travers l'endroit

de l'histoire qui se recompose

qui sait où lui brille les yeux

dans cette face plus rose que les roses

un jour cette jeune fille s'approche de lui

tous deux s'assoient au bord de mer

vision alors de la mer et des mouettes

pirouettant autour d'eux zig-zig-zig

elle lui demande s'il ne l'aime plus

elle l'aime et n'en aime aucun autre

il la tient dans ses bras et lui raconte

toute l'histoire de son chagrin et

de son désir d'elle et de son amour

je t'aime je t'aime répète-t-il

et comme il se penche sur elle pour l'embrasser

il s'aperçoit qu'elle est morte

car pendant qu'il lui parlait de son amour

il l'avait étouffée dans ses bras

tu vois la jeune fille n'avait

qu'un mouvement à faire

elle n'a pas voulu

c'est inexprimable

comment se rappeler un geste pas vraiment commencé

comment le corps bouge-t-il

comment fait le corps dans cette toile

de mouvements à accomplir

comment fait-il pour se lever pour s'asseoir

pour ramasser un caillou

la tête est en haut

elle repose sur le cou

le cou retient les épaules

les épaules rattrapent les bras

dans toute cette construction de chute

le jeu consiste à conserver son équilibre

la mise de ce jeu incompréhensible

c'est l'attraction terrestre elle nous tient

verticale comme une porte définitive

je connais un jeu beaucoup plus drôle

celui de la percussion dans le boléro de Ravel

il faut diviser la série répétitive en quatre parties

d'abord quatre coups de poing sur le tambour c'est I

ensuite quatre coups de poing plus deux c'est II

reviennent les quatre coups de poing et c'est III

enfin dix coups sur le tambour et c'est IV

en s'exerçant sur une table de cuisine cela donne

pan pan pan pan

pan pan pan pan pan pan

pan pan pan pan

pan pan pan pan pan pan pan pan pan pan

un peu lassant mais très joli

ça dure depuis plus de cinquante ans

facilement transmissible et plus simple

que le jeu des couleurs alternées

je regarde une chaise dans ma chambre

le dos est formé par des bâtons de bois

noir et clair alternant j'en compte huit

trois noirs sur fond jaune

cinq jaunes sur fond noir

je m'amuse à mettre le ton alternativement

ou sur le clair ou sur le noir

le sens se change chaque fois

en son contraire

maintenant je vais te raconter

une histoire chinoise

il était une fois un chinois et une chinoise très pauvres

ils vivaient dans leur cabane au bord d'une rivière

ils eurent un enfant et comme ils étaient très pauvres

ils ne pouvaient pas le garder

une nuit l'homme prit l'enfant

la lune luisait sur la rivière

il le jeta dans l'eau

un an plus tard ils eurent encore un enfant

ils étaient toujours très pauvres et ne pouvaient le garder

une nuit l'homme repartit à la rivière

et jeta l'enfant dans l'eau

la lune brillait sur la rivière

un an plus tard ils eurent un troisième enfant

ils n'étaient plus aussi pauvres et ils le gardèrent

lorsqu'il fut un peu grand le père l'emmena à la ville

lorsqu'ils regagnèrent leur cabane il faisait nuit

la lune luisait sur la rivière

l'enfant dit «regarde père la beauté de la lune

qui brille sur la rivière

exactement comme les deux nuits

au cours desquelles tu m'as noyé»

c'est une histoire effrayante

et magnifique n'est-ce pas

mais n'arrose pas mes cendres

d'un inutile poison

I'm a foot-ball disait un ami en regardant

ses pieds croisés et ses jambes allongées

devant lui dans le wagon du train

qui nous ramenait de Royaumont

où sur les canaux verdâtres chargés de feuilles rouges

plus aucun cygne ne passe Royaumont

où j'avais appris que l'histoire de l'attelage

aux quarante boeufs[*] rassemblés

pour abattre la tour haute de l'abbaye

au début de la révolution française

est une histoire fausse tant mieux

la plupart des histoires qui circulent sur les révolutions

mises en place comme celle de l'attelage phénoménal

sont des inventions des rumeurs crevées

répandues sur les auditoires populaires

pour émouvoir pour faire sursauter

ce qu'il ne faut pas faire bouger

mais parle parle toi bouche

tes lèvres forment une longue vie

tu racontais comment dire des choses

qui ne se rencontraient pas

je ris encore de ta figure perplexe

devant la progression de l'histoire

la vague d'une nouvelle montée solide

qui se vide et disparaît

derrière la brume d'obscurité naissante

ce que l'on désigne par la chute du jour

qui tombe en effet qui tombe

dans les balancements de ses plumes

et le bain des enfants la table à thé

l'ombre des arbres en face de la maison éclairée

quel moment de passage sombre étroit

l'abîme impossible à franchir d'un saut

je n'oublie aucun détail

de ces choses que je raconte pour toi

tout le reste tu le sais déjà

mais peut-être n'as-tu jamais remarqué

qu'au cinéma lorsqu'à l'écran

le trottoir est mouillé par la pluie

alors on recule ses pieds dans la salle

de crainte qu'ils soient mouillés aussi