Cochlear Implants

Cochlear implants, a technology that permits individuals with profound hearing loss to receive auditory cues, have had a very

different reception than IOLs. Unlike implanted lenses that diffused rapidly to millions of elderly, cochlear implants have not fared well. Indeed, Medicare reimbursement was made for only sixty-nine such implants in fiscal 1987, despite estimates that sixty thousand to two hundred thousand Americans could benefit from the device. Many industrial competitors never entered the field or have since abandoned it, leaving only three firms still in the market in 1990. This medical device has met resistance throughout its history, and the collective impact of policy hurdles has been profound.

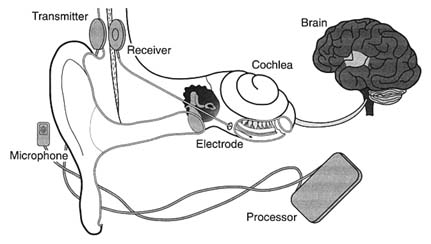

The cochlea, a structure in the inner ear, translates sounds from mechanical vibrations to electrical signals. These signals are produced by cells in the cochlea. The cells have a fringe of tiny hairs that bend in response to vibrations in the outer and middle ear. Those responses produce electrical signals that stimulate the auditory nerve and send messages that the brain interprets as sound.[36]

Nancy M. Kane and Paul D. Manoukian, "The Effect of the Medicare Prospective Payment System on the Adoption of New Technology: The Case of Cochlear Implants," New England Journal of Medicine 321 (16 November 1989): 1378-1383.

This natural system of hearing is versatile enough to transmit the full range of sounds. If the hair cells in the cochlea are damaged by injury or disease, the individual is condemned to deafness. Over two hundred thousand Americans suffer this profound hearing loss, and conventional hearing aids are useless for them. Cochlear implants, at least at this stage of development, cannot restore the world of sound. They do allow for reception of sounds such as sirens and voices, auditory cues that are vital for safety and for some social interactions. But the recipient of the implant cannot hear normal conversation.

The possibility of producing useful hearing by electrical stimulation of the cochlea occurred by accident.[37]

Robin P. Michelson, "Cochlear Implants: Personal Perspectives," in Robert A. Schindler and Michael M. Merzenich, eds., Cochlear Implants (New York: Raven Press, 1985), 9-11.

When an amplifier used in the operating room to monitor the cochlear response oscillated, the patient heard a very high-pitched tone. Some early work on this type of induced stimulation was published in 1955 and 1956.[38]William F. House, "A Personal Perspective on Cochlear Implants," in Schindler and Merzenich, Cochlear Implants, 13.

Researchers undertook additional work during the early 1960s, but they encountered significant problems. Among the barriers were included adverse patient reactions to the insulating silicone rubber used in the first primitive devices and concern about the effects of long-term stimulation on all auditory sensation. In 1965, the results of studies were submittedto the American Otological Society but were rejected as too controversial for presentation.

As implant technology improved in the late 1960s, some of the problems were resolved, but concerns over ethics and long-term effects still dogged the technology. The National Institutes of Health did not provide any funding for the scientific research, a refusal that some scientists in the field attributed to the bias against biomedical engineering among NIH peer review groups.[39]

See the discussion in chapter 3 on an antiengineering bias at the NIH.

Several policy breakthroughs occurred in the 1970s, when the NIH focus began to shift toward goal oriented, or targeted, programs that would produce identifiable results. The NIH established an intramural program to investigate cortical and subcortical stimulation, primarily for blindness but also for other neurological disorders. While hearing stimulation was not an important part of the original program, it became of greater interest when the research on cortical visual implants appeared clearly unsuccessful. In 1977, the NIH instituted an independent assessment of patients with cochlear implants. The Bilger Report, produced at the University of Pittsburgh, concluded that these products were a definite aid to communication.[40]

R. C. Bilger et al., "Evaluation of Subjects Presently Fitted with Implanted Auditory Prostheses," Annals of Otolaryngology, Rhinology and Laryngology, supplement 38 (1977) 86: 3-10. Discussed in F. Blair Simmons, "History of Cochlear Implants in the United States: A Personal Perspective," in Schindler and Merzenich, Cochlear Implants, 1-7.

Seven years later, in November 1984, the FDA approved the design of a single-channel device for cochlear implantation. The 3M Company produced the device in conjunction with Dr. William House, an early researcher and chief inventor. The device consisted of a receiver similar to that of a hearing aid, a speech-processing minicomputer that transforms the sound signals into electrical signals, another receiver for those electrical signals that is implanted under the skin above and behind the ear, and a thin wire inserted surgically through the mastoid bone into the cochlea to transmit the signals (see figure 23).

By 1985 a handful of companies had entered the market. The 3M Company was the clear leader with the only approved product. Others included the Nucleus Group, an Australian company and parent of the U.S. Cochlear Corporation, Biostim, and Symbion, an outgrowth of research at the University of Utah.[41]

Biomedical Business International 8 (29 March 1985): 47-48.

A private industry group reported that leading hearing-aid manufacturers did not enter the marketplace because "the FDA-related

Figure 23. The cochlear implant.

Source: The 3M Company, Cochlear Implant System, n.d.

expense of developing and testing such devices is prohibitive." It was reported that 3M had budgeted over $15 million for cochlear implant development.

Once approved by the FDA, the device faced the hurdle of Medicare's coverage and payment decision. After several years of deliberation, and following endorsement of the device by the AMA in 1983 and the American Academy of Otolaryngology in 1985, Medicare issued a favorable coverage ruling for both single-channel and multichannel devices in September 1986. The next step was for HCFA to assign the technology to a code which would then provide the means for establishing appropriate levels of payment for procedures.[42]

Kane and Manoukian, "The Effect of Medicare," 1379.

HCFA has considerable discretion in the placement of a new procedure into the DRG system. If the device is assigned to a DRG that does not cover the cost during the diffusion period, hospitals implanting the devices will lose money. Hospitals that increase the proportion of cases involving these devices lower their operating margins in those DRGs. ProPAC recommended in 1987 that the cochlear implant be assigned to a device specific, temporary DRG. HCFA did not follow ProPAC's recommendation. Instead, in May 1988 the agency announced a DRG placement

that would not pay the full estimated cost of $14,000 for the implantation of the device.[43]

Ibid., 1380.

Evidence accumulated that hospitals had a strong disincentive to provide cochlear implantation. Ten percent of the 170 hospitals involved openly acknowledged to researchers that they restricted implantations because of the loss of $3,000 to $5,000 for each Medicare case.[44]

Ibid., citing Cochlear Corporation personal communication.

These policies limited the size of the market and deeply affected the private sector producers. The 3M Company stopped marketing the single-channel model actively and halted research on multichannel devices because of the low use rate of both models. The small market discouraged additional investment. There were five firms that developed cochlear implants for the U.S. market from 1978 through 1985. By 1990, three had left and there were no new entrants with FDA approved devices.[45]

Ibid.

It was undisputed that this new technology had limitations, but it also was recognized as useful and beneficial to certain classes of patients. The policy environment was relatively unresponsive to early development. The quest for FDA approval was difficult, time-consuming, and costly. The response of HCFA to the technology was definitely obstructionist. The future of the research and development of this area of technology is now in doubt.

The primary effect of the payment policy has been uncertainty in the marketplace. Firms can no longer count upon growth in their particular market segment. Incremental policy changes are frequent and can have catastrophic effects on the markets for some products. In addition, cost-containment policies have introduced new hurdles to market access, which cause higher costs and delays even for successful new entrants.

Cost control has become an important value in the distribution of medical devices. It presents significant problems because the costs of a new technology are difficult to predict before distribution. Some products may have cost-reducing potential that is not known in the early stages or additional beneficial applications that will emerge during use. It is legitimate to ask how much cost should matter and who should decide that issue.

In addition, the case studies illustrate how complex the policy environment was in 1990. There are significant hurdles at virtually

every stage of innovation. Even promoters such as NIH can place barriers in the paths of the innovators. NIH disapproval can act as a deterrent, as the early years of cochlear implant development reveal. HCFA, once a source of nearly unlimited funds, can significantly delay or even bar technology from the marketplace.

Our medical device patient is now a confirmed recipient of polypharmacy, as the prescriptions have proliferated over time. Before we turn to the prognosis, however, it is necessary to look at the international marketplace. Does the world market provide an outlet for manufacturers constrained by cost controls in the United States? Or are international firms a competitive threat both in the United States and abroad?